Abstract

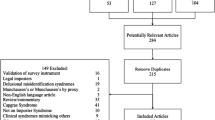

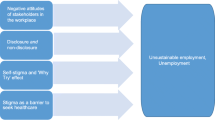

Purpose Mental health conditions (MHC) are an increasing reason for claiming injury compensation in Australia; however little is known about how these claims are managed by different gatekeepers to injury entitlements. This study, drawing on the views of four stakeholders—general practitioners (GPs), injured persons, employers and compensation agents, aims to describe current management of MHC claims and to identify the current barriers to return to work (RTW) for injured persons with a MHC claim and/or mental illness. Methods Ninety-three in-depth interviews were undertaken with GPs, compensation agents, employers and injured persons. Data were collected in Melbourne, Australia. Thematic techniques were used to analyse data. Results MHC claims were complex to manage because of initial assessment and diagnostic difficulties related to the invisibility of the injury, conflicting medical opinions and the stigma associated with making a MHC claim. Mental illness also developed as a secondary issue in the recovery process. These factors made MHC difficult to manage and impeded timely RTW. Conclusions It is necessary to undertake further research (e.g. guideline development) to improve current practice in order to enable those with MHC claims to make a timely RTW. Further education and training interventions (e.g. on diagnosis and management of MHC) are also needed to enable GPs, employers and compensation agents to better assess and manage MHC claims.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

WorkSafe Victoria. Stress (2013). http://www.worksafe.vic.gov.au/safety-and-prevention/health-and-safety-topics/stress. Accessed 30 May 2013.

Guthrie R, Ciccarelli M, Babic A. Work-related stress in Australia: the effects of legislative interventions and the cost of treatment. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2010;33:101–15.

Cohen D, Kinnersley P. Sickness certification and stress: reviewing the challenges. Primary Care Mental Health. 2005;3:201–4.

Tennant C. Work-related stress and depressive disorders. J Psychosom Res. 2001;51:697–704.

Murphy LR. Stress management in work settings: a critical review of the health effects. Am J Health Promot. 1996;11:112–35.

Medibank Private. The cost of workplace stress in Australia. 2013. http://www.medibank.com.au/Client/Documents/Pdfs/The-Cost-of-Workplace-Stress.pdf. Accessed 30 May 2013.

LaMontagne AD, Keegel T, Louie AM, Ostry A. Job stress as a preventable upstream determinant of common mental disorders: a review for practitioners and policy-makers. Adv Mental Health. 2010;9:17–35.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Work-related injuries 2009-10. ABS cat. no. 6324.0. Canberra: ABS; 2010.

Kirsh B, Slack T, King CA. The nature and impact of stigma towards injured workers. J Occ Rehab. 2012;22:143–54.

Safe Work Australia. Compendium of workers’ compensation statistics Australia 2009-10. Canberra: Safe Work Australia; 2012.

Hensing G, Andersson L, Brage S. Increase in sickness absence with psychiatric diagnosis in Norway: a general population-based epidemiologic study of age, gender and regional distribution. BMC Med. 2006;. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-4-19.

Brown J, Hanlon P, Turok I, Webster D, Arnott J, Macdonald EB. Mental health as a reason for claiming incapacity benefit–a comparison of national and local trends. J Public Health. 2009;31:74–80.

Laitinen-Krispijn S, Bijl RV. Mental disorders and employee sickness absence: the NEMESIS study. Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatry Epidemiol. 2000;35:71–7.

Bultmann U, Christensen KB, Burr H, Lund T, Rugulies R. Severe depressive symptoms as predictor of disability pension: a 10-year follow-up study in Denmark. Eur J Public Health. 2008;18:232–4.

WorkSafe Victoria. Workers: the claims process. 2014. http://www.worksafe.vic.gov.au/injury-and-claims/workers-the-claims-process/if-you-have-sustained-a-work-related-injury-or-illness. Accessed 7 Jan 2014.

Transport Accident Commission. Claims and support. 2014. http://www.tac.vic.gov.au/claims. Accessed 7 Jan 2014.

Dembe AE, Mastroberti MA, Fox SE, Bigelow C, Banks SM. Inpatient hospital care for work-related injuries and illnesses. Am J Ind Med. 2003;44:331–42.

Ruseckaite R, Gabbe B, Vogel AP, Collie A. Health care utilisation following hospitalisation for transport-related injury. Injury. 2012;43:1600–5.

Chang D, Irving A. Evaluation of the GP education pilot: health and work in general practice. London: Department for Work and Pensions; 2008.

Sterling M, Hendrikz J, Kenardy J, Kristjansson E, Dumas JP, Niere K, Cote J, Deserres S, Rivest K, Jull G. Assessment and validation of prognostic models for poor functional recovery 12 months after whiplash injury: a multicentre inception cohort study. Pain. 2012;153:1727–34.

Nordin M, Cedraschi C, Skovron ML. Patient-health care provider relationship in patients with non-specific low back pain: a review of some problem situations. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1998;12:75–92.

Kosny A, MacEachen E, Ferrier S, Chambers L. The role of health care providers in long term and complicated workers’ compensation claims. J Occ Rehab. 2012;21:582–90.

Östlund GM, Borg KE, Wide P, Hensing GKE, Alexanderson KAE. Clients’ perceptions of contact with professionals within healthcare and social insurance offices. Scand J Public Health. 2003;31:275–82.

Mussener U, Svensson T, Soderberg E, Alexanderson K. Encouraging encounters: sick-listed persons’ experiences of interactions with rehabilitation professionals. Soc Work Health Care. 2008;46:71–87.

Anema J, Jettinghoff K, Houtman I, Schoemaker C, Buijs P, van den Berg R. Medical care of employees long-term sick listed due to mental health problems: a cohort study to describe and compare the care of the occupational physician and the general practitioner. J Occ Rehab. 2006;16:38–49.

Franche R-L, Carnide N, Hogg-Johnson S, Cote P, Breslin FC, Bultmann U, Severin CN, Krause N. Course, diagnosis and treatment of depressive symptomatology in workers following a workplace injury: a prospective cohort study. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54:534–46.

Hamm RM, Reiss DM, Paul RK, Bursztajn HJ. Knocking at the wrong door: insured workers’ inadequate psychiatric care and workers’ compensation claims. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2007;30:416–26.

Blank L, Peters J, Pickvance S, Wilford J, MacDonald E. A systematic review of the factors which predict return to work for people suffering episodes of poor mental health. J Occ Rehab. 2008;18:27–34.

Wynne-Jones G, Mallen CD, Mottram S, Main CJ, Dunn KM. Identification of UK sickness certification rates, standardised for age and sex. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59:510–6.

Campbell A, Ogden J. Why do doctors issue sick notes? An experimental questionnaire study in primary care. Fam Pract. 2006;23:125–30.

Collie A, Ruseckaite R, Brijnath B, Kosny A, Mazza D. Sickness certification of workers compensation claimants by general practitioners in Victoria, 2003–2010. MJA. 2013;199:480–3.

Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. The Sage handbook of qualitative research. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2011.

Cohen D, Marfell N, Webb K, Robling M, Aylward M. Managing long-term worklessness in primary care: a focus group study. Occup Med. 2010;60:121–6.

Cohen D, Aylward M, Rollnick S. Inside the fitness for work consultation: a qualitative study. Occup Med. 2009;59:347–52.

Ryan GW, Bernard HR. Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods. 2003;15:85–109.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101.

Strauss A, Corbin J. Grounded theory methodology: an overview. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1994. p. 273–85.

Olszewski B, Macey D, Lindstrom L. The practical work of < coding > : an ethnomethodological inquiry. Human Stud. 2006;29:363–80.

Mays N, Pope C. Qualitative research in health care. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ. 2000;320:50–2.

Whittemore R, Chase SK, Mandle CL. Validity in qualitative research. Qual Health Res. 2001;11:522–37.

Chong CS, Tsunaka M, Tsang HW, Chan EP, Cheung WM. Effects of yoga on stress management in healthy adults: a systematic review. Altern Ther Health Med. 2011;17:32–8.

Arent SM, Landers DM, Etnier JL. The effects of exercise on mood in older adults: a meta-analytic review. J Aging Phys Act. 2000;8:407–30.

Krause N, Frank JW, Dasinger LK, Sullivan TJ, Sinclair SJ. Determinants of duration of disability and return-to-work after work-related injury and illness: challenges for future research. Am J Ind Med. 2001;40:464–84.

Dibben P, Wood G, Nicolson R, O’Hara R. Quantifying the effectiveness of interventions for people with common health conditions in enabling them to stay in or return to work: A rapid evidence assessment. London: Department of Work and Pensions; 2012.

Black C. Working for a healthier tomorrow: review of the health of Britain’s working age population. London: TSO; 2008.

Bültmann U, Franche R-L, Hogg-Johnson S, Côté P, Lee H, Severin C, Vidmar M, Carnide N. Health status, work limitations, and return-to-work trajectories in injured workers with musculoskeletal disorders. Qual Life Res. 2007;16:1167–78.

Waddell G, Burton A. Is work good for heath and well being?. London: TSO; 2006.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the technical advice and support of Ms Natalie Bekis, Ms Louise Goldman, Ms Tamara Fitzgerald and Mr Jamie Swann, from WorkSafe Victoria and the TAC, for their assistance with recruitment. We also thank Ms Amy Allen for assistance with data collection and analysis. Finally, we express our gratitude to the individuals who participated in the study. This project was funded by the Institute for Safety, Compensation and Recovery Research (ISCRR). ISCRR is a joint initiative of WorkSafe Victoria, the Transport Accident Commission and Monash University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brijnath, B., Mazza, D., Singh, N. et al. Mental Health Claims Management and Return to Work: Qualitative Insights from Melbourne, Australia. J Occup Rehabil 24, 766–776 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-014-9506-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-014-9506-9