Abstract

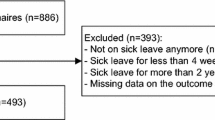

Introduction The present study aimed to gain insight in the predictors of full return to work (RTW) among employees on long-term sick leave due to three different self-reported reasons for sick leave: physical, mental or co-morbid physical and mental problems. This knowledge can be used to develop diagnosis-specific interventions that promote earlier RTW. Methods This prospective cohort study with a two-year follow-up employs a sample of 682 Dutch employees, sick-listed for 19 weeks (SD = 1.68), who filled out two questionnaires: at 19 weeks and 2 years after the start of sick leave. The dependent measure was duration until full RTW, the independent measures were cause of sick leave, health characteristics, individual characteristics and work characteristics. Results Reporting both physical and mental problems as reasons for sick leave was associated with a longer duration until full RTW. Nonparametric Cox survival analysis showed that partial RTW at baseline and lower age were strong predictors of earlier RTW in all three groups, and that RTW self-efficacy predicted earlier RTW in two groups. Other predictors of full RTW varied among groups. Conclusions Tailoring for different reasons for sick leave might improve the effects of new interventions because the predictors of full RTW differ among groups. Enhancement of partial RTW and RTW self-efficacy may be relevant components of any intervention, as these were predictors of full RTW in at least two groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Goetzel RZ, Long SR, Ozminkowski RJ, Hawkins K, Wang S, Lynch W. Health, absence, disability, and presenteeism. Cost estimates of certain physical and mental health conditions affecting U.S. employers. J Occup Environ Med. 2004;46:398–412.

TNS Opinion & Social. Mental well-being. European Commission, 2006. URL: http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_information/documents/ebs_248_en.pdf (accessed 20 January 2011).

Lagerveld SE, Bültmann U, Franche RL, Van Dijk FJH, Vlasveld MC, Van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, et al. Factors associated with work participation and work functioning in depressed workers: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20:275–92.

Stress impact consortium. Integrated report of stress impact: on the impact of changing social structures on stress and quality of life: individual and social perspectives. 2006. URL: http://www.fahs.surrey.ac.uk/stress_impact/publications/wp8/Stress%20Impact%20Integrated%20Report.pdf (accessed 11 December 2008).

Krause N, Dasinger LK, Deegan LJ, Rudolph L, Brand RJ. Psychosocial job factors and return-to-work after compensated low back injury: a disability phase-specific analysis. Am J Ind Med. 2001;40:374–92.

Van der Giezen AM, Bouter LM, Nijhuis FJ. Prediction of return-to-work of low back pain patients sicklisted for 3–4 months. Pain. 2000;87:285–94.

Houtman ILD, Schoemaker CG, Blatter BM, De Vroome EMM, Van den Berg R, Bijl RV. Psychische klachten, interventies en werkhervatting. De prognosestudie INVENT [Psychological complaints, interventions and return to work: The prognosis study INVENT]. Heerhugowaard, The Netherlands: PlantijnCasparie, 2002.

Vowles KE, Gross RT, Sorrell JT. Predicting work status following interdisciplinary treatment for chronic pain. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:359–69.

Brouwers EPM, Terluin B, Tiemens BG, Verhaak PFM. Predicting return to work in employees sick-listed due to minor mental disorders. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19:323–32.

Blank L, Peters J, Pickvance S, Wilford J, MacDonald E. A systematic review of the factors which predict return to work for people suffering episodes of poor mental health. J Occup Rehabil. 2008;18:27–34.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215.

Lagerveld SE, Blonk RWB, Brenninkmeijer V, Schaufeli WB. Return to work among employees with mental health problems: development and validation of a self-efficacy questionnaire. Work Stress. 2010;24:359–76.

Renegold M, Sherman MF, Fenzel M. Getting back to work: self-efficacy as a predictor of employment outcome. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 1999;22:361–7.

Brouwer S, Reneman MF, Bültmann U, Van der Klink JJL, Groothoff JW. A prospective study of return to work across health conditions: perceived work attitude, self-efficacy and perceived social support. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20:104–12.

Robbins RA, Moody DS. Psychological testing variables as predictors of return to work by chronic pain patients. Percept Mot Skills. 1996;83:1317–8.

Penley JA, Tomaka J, Wiebe JS. The association of coping to physical and psychological health outcomes: a meta-analytic review. J Behav Med. 2002;25:551–603.

Pisarski A, Bohle P, Callan VJ. Effects of coping strategies, social support and work-nonwork conflict on shift worker’s health. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1998;24(suppl 3):141–5.

Van Rhenen W, Schaufeli WB, Van Dijk FJH, Blonk RWB. Coping and sickness absence. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2008;81:461–72.

Janssen N, Van den Heuvel WP, Beurskens AJ, Nijhuis FJ, Schroer CA, Van Eijk JT. The demand-control-support model as predictor of return to work. Int J Rehabil Res. 2003;26:1–9.

Nieuwenhuijsen K, Verbeek JHAM, De Boer AGEM, Blonk RWB, Van Dijk FJH. Supervisory behavior as a predictor of return to work in employees absent from work due to mental health problems. Occup Environ Med. 2004;61:817–23.

Post M, Krol B, Groothoff JW. Work-related determinants of return to work of employees on long-term sickness absence. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27:481–8.

Anema JR, Schellart AJM, Cassidy JD, Loisel P, Veerman TJ, Van der Beek AJ. Can cross country differences in return-to-work after chronic occupational back pain be explained? An exploratory analysis on disability policies in a six country cohort study. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19:419–26.

Franche RL, Krause N. Readiness for return to work following injury or illness: conceptualizing the interpersonal impact of health care, workplace, and insurance factors. J Occup Rehabil. 2002;12:233–56.

Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med. 1994;1994(10):77–84.

Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. STAI manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, California: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970.

Schreurs PJG., Van de Willige G, Brosschot JF, Tellegen B, Graus GMH. De Utrechtse Copinglijst: UCL. Omgaan met problemen en gebeurtenissen [The Utrecht Coping List: UCL. Coping with problems and events]. Lisse, The Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger, 1993.

Karasek RA, Brisson C, Kawakami N, Houtman I, Bongers P, Amick B. The job content questionnaire (JCQ): an instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. J Occup Health Psychol. 1998;3:322–55.

Buist-Bouwman MA, De Graaf R, Vollebergh WAM, Ormel J. Comorbidity of physical and mental disorders and the effect on work-loss days. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;111:436–43.

Nordin M, Hiebert R, Pietrek M, Alexander M, Crane M, Lewis S. Association of comorbidity and outcome in episodes of nonspecific low back pain in occupational populations. J Occup Environ Med. 2002;44:677–84.

Hensing G, Spak F. Psychiatric disorders as a factor in sick-leave due to other diagnoses. A general population-based study. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:250–6.

Ormel J, Koeter MWJ, Van den Brink W, Van de Willige G. Recognition, management, and course of anxiety and depression in general practice. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:700–6.

Foa EB, Hembree EA, Cahill SP, Rauch AM, Riggs DS, Feeny NC, et al. Randomized trial of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder with and without cognitive restructuring: outcome at academic and community clinics. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:953–64.

Öst L-G, Thulin U, Ramnerö J. Cognitive behavior therapy vs exposure in vivo in the treatment of panic disorder with agrophobia. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42:1105–27.

Van Balkom AJLM, Bakker A, Spinhoven P, Blaauw BMJ, Bart MJW, Smeenk S, et al. A meta-analysis of the treatment of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia: a comparison of psychopharmacological, cognitive-behavioral, and combination treatments. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997;185:510–6.

Blonk RWB, Brenninkmeijer V, Lagerveld SE, Houtman ILD. Return to work: a comparison of two cognitive behavioural interventions in cases of work-related psychological complaints among the self-employed. Work Stress. 2006;20:129–44.

Krause N, Dasinger LK, Neuhauser F. Modified work and return to work: a review of the literature. J Occup Rehabil. 1998;8:113–39.

Van der Klink JJL, Blonk RWB, Schene AH, Van Dijk FJH. Reducing long term sickness absence by an activating intervention in adjustment disorders: a cluster randomised controlled design. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60:429–37.

Hope DA, Heimberg RG, Bruch MA. Dismantling cognitive-behavioral group therapy for social phobia. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33:637–50.

Tryon WW. Possible mechanisms for why desensitization and exposure therapy work. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25:67–95.

Wasiak R, Young AE, Roessler RT, McPherson KM, Van Poppel MN, Anema JR. Measuring return to work. J Occup Rehabil. 2007;17:766–81.

Baruch Y, Holtom BC. Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Hum Relat. 2008;61:1139–60.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Huijs, J.J.J.M., Koppes, L.L.J., Taris, T.W. et al. Differences in Predictors of Return to Work Among Long-Term Sick-Listed Employees with Different Self-Reported Reasons for Sick Leave. J Occup Rehabil 22, 301–311 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-011-9351-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-011-9351-z