Abstract

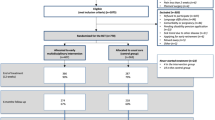

Introduction In an earlier study, Gatchel et al. (J Occup Rehabil 13:1–9, 2003) demonstrated that participants at high risk for developing chronic low back pain disability (CLBPD), who received a biopsychosocial early intervention treatment program, displayed significantly more symptom improvement, as well as cost savings, relative to participants receiving standard care. The purpose of the present study was to expand on these results by examining whether the addition of a work-transition component would further strengthen the effectiveness of this early intervention treatment. Methods Using an existing algorithm, participants were identified as being high-risk (HR) or low-risk (LR) for developing CLBPD. HR participants were then randomly assigned to one of three groups: early intervention (EI); early intervention with work transition (EI/WT); or standard care (SC). Participants provided information regarding pain, disability, work status, and psychosocial functioning at baseline, periodically during treatment, and again 1 year following completion of treatment. Results At 1-year follow-up, no significant differences were found between the EI and EI/WT groups in terms of occupational status, self-reports of pain and disability, coping ability or psychosocial functioning. However, significant differences in all these outcomes were found comparing these groups to standard care. Conclusion The addition of a work transition component to an early intervention program for the treatment of ALBP did not significantly contribute to improved work outcomes. However, results further support the effectiveness of early intervention for high-risk ALBP patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Gatchel RJ, et al. Treatment- and cost-effectiveness of early intervention for acute low-back pain patients: a one-year prospective study. J Occup Rehabil. 2003;13(1):1–9.

Andersson GB. The epidemiology of spinal disorders. In: Frymoyer JW, editor. The adult spine: principles and practice. Philadelphia: Lippencott-Raven; 1997. p. 93–133.

Picavet HS, Schouten JS, Smit HA. Prevalences and consequences of low back pain problems in the Netherlands, working vs non-working population, the MORGEN-study. Public Health. 1999;113:73–7.

Kelsey JL. Epidemiology and impact of low-back pain. Spine. 1980;5(2):133–42.

Von Korff M, et al. Chronic spinal pain and physical-mental comorbidity in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Pain. 2005;113(3):331–9.

Von Korff M, Saunders K. The course of back pain in primary care. Spine. 1996;21(24):2833–7.

Frymoyer JW, Cats-Baril WL. An overview of the incidences and costs of low back pain. Orthop Clin North Am. 1991;22(2):263–71.

Mayer TG, Gatchel RJ. Functional restoration for spinal disorders: the sports medicine approach. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1988.

National Center for Health Statistics. Health, 2005. With chartbook on trends in the health of Americans. Maryland: Hyattsville; 2005.

Straus BN. Chronic benign pain syndromes: the cost of intervention. Spine. 2003;27:2614–9.

De Lissovoy G, et al. Cost-effectiveness of long-term intrathecal morphine therapy for pain associated with failed back surgery syndrome. Clin Ther. 1997;19(1):96–112. discussion 84-5.

National Research Council. Musculoskeletal disorders the workplace: low back, upper extremities. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 2001.

Linton SJ, editor. New avenues for the prevention of chronic musculoskeletal pain and disability. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2002.

Gatchel RJ, Polatin P, Mayer T. The dominant role of psychosocial risk factors in the development of chronic low back pain disability. Spine. 1995;20(24):2702–9.

Gatchel RJ, Polatin PB, Kinney RK. Predicting outcome of chronic back pain using clinical predictors of psychopathology: a prospective analysis. Health Psychol. 1995;14(5):415–20.

Linton SJ, Bradley LA. Strategies for the prevention of chronic pain. In: Gatchel RJ, Turk DC, editors. Psychological approaches to pain management: a practitioner’s handbook. New York: Guilford Publications, Inc; 1996.

van Der Giezen AM, Bouter LM, Nijhuis FJN. Prediction of return-to-work of low back pain patients sick listed for 3–4 months. Pain. 2000;87:285–94.

Teasell RW, Bombardier C. Employment-related factors in chronic pain and chronic pain disability. Clin J Pain. 2001;December 2001 supplement:S39–S45.

McLellan RK, Pransky G, Shaw WS. Disability management training for supervisors: A pilot inventory program. J Occup Rehabil. 2001;11:33–42.

Marhold C, Linton SJ, Melin L. Identification of obstacles for chronic pain patients to return to work: evaluation of a questionnaire. J Occup Rehabil. 2002;12:65–76.

Koopman C, et al. Stanford presenteeism scale: health status and employee productivity. J Occup Environ Med. 2002;44(1):14–20.

Million S, et al. Assessment of the progress of the back-pain patient. 1981 Volvo Award in Clinical Science. Spine. 1982;7:204–12.

Dworkin SF, LeResche L. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders. J Craniomandib Disord. 1992;6:301–55.

Ware JE, et al. SF-36 health survey: manual and interpretation guide. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1993.

SPSS. SPSS for windows. Chicago: SPSS Inc.; 2008.

Siddiqui O, Ali MW. A comparison of the random-effects pattern mixture model with last-observation-carried-forward (LOCF) analysis in longitudinal clinical trials with dropouts. J Biopharm Stat. 1998;8(4):545–63.

Ostelo RW, et al. Interpreting change scores for pain and functional status in low back pain: towards international consensus regarding minimal important change. Spine. 2008;33(1):90–4.

Jensen IB, et al. A 3-year follow-up of a multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme for back and neck pain. Pain. 2005;115(3):273–83.

Loisel P, et al. A population-based, randomized clinicl trial on back pain management. Spine. 1997;22:2911–8.

Côté P, et al. Patterns of sick-leave and health outcomes in injured workers with back pain. Eur Spine J. 2008;17(4):484–93.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The writing of this article was supported in part by grants to Dr. Gatchel from the National Institutes of Health (3R01 MH 046452, 1K05 MH 071892).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Whitfill, T., Haggard, R., Bierner, S.M. et al. Early Intervention Options for Acute Low Back Pain Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial with One-Year Follow-Up Outcomes. J Occup Rehabil 20, 256–263 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-010-9238-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-010-9238-4