Abstract

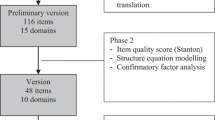

Introduction: Musculoskeletal disorders are among the main causes of short- and long-term disability. Aim: Identify the methods for assessing multidimensional components of illness representations. Methods: An electronic literature search (French, English) from 1980 to the present was conducted in medical, paramedical and social science databases using predetermined key words. After screening titles and abstracts based on a specific set of criteria, sixty-four articles were reviewed. Results: Qualitative approaches for assessing illness representation were found mainly in the fields of anthropology and sociology and were based on the explanatory models of illness. The interviews reviewed were: the Short Explanatory Model Interview, the Explanatory Model of Illness Catalogue and the McGill Illness Narrative Interview. Quantitative approaches were found in the health psychology field and used the following self-administered questionnaires: the Survey of Pain Attitudes, the Pain Beliefs and Perceptions Inventory, the Pain Beliefs Questionnaire, the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire, the Implicit Model of Illness Questionnaire, the Illness Perception Questionnaire, including its derivatives, and the Illness Cognition Questionnaire. Conclusion: This review shows the actual use and existence of multiple interviews and questionnaires in assessing multidimensional illness representations. All have been used and/or tested in a medical context but none have been tested in a work disability context. Further research will be needed to determine their suitability for use in a work disability context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

(1) What do you call your problem? What name does it have? (2) What do you think has caused your problem? (3) Why do you think it started when it did? (4) What does your sickness do to you? How does it work? (5) How severe is it? Will it have a short or long course? (6) What do you fear most about your sickness? (7) What are the chief problems your sickness has caused for you? (8) What kind of treatment do you think you should receive? What are the most important results you hope to receive from the treatment?

References

CSST. Statistiques sur les affections vertébrales, 1998–2001. Québec: CSST; 2002.

CSST. Statistiques sur les lésions en “ITE” du système musculo-squelettique. Québec: CSST; 2002.

Wyatt W. Staying at work. Making the connection to a healthy organization. Worldwide; 2005.

Canada H. Economic burden of illness in Canada. Ottawa: Health Canada; 1998.

Rivero-Arias O, Campbell H, Gray A, Fairbank J, Frost H, Wilson-MacDonald J. Surgical stabilisation of the spine compared with a programme of intensive rehabilitation for the management of patients with chronic low back pain: cost utility analysis based on a randomised controlled trial. Br Med J. 2005;330:1239–45. doi:10.1136/bmj.38441.429618.8F.

Henderson M, Glozier N, Elliott KH. Long term sickness absence. Br Med J. 2005;330:802–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7495.802.

Loisel P, Durand M-J, Baril R, Langley A, Falardeau M. Décider pour faciliter le retour au travail: Étude exploratoire sur les dimensions de la prise de décision dans une équipe interdisciplinaire de réadaptation au travail. Montréal: Institut de recherche Robert-Sauvé en santé et sécurité au travail (IRSST); 2004.

Baril R, Durand MJ, Coutu MF, Côté D, Cadieux G, Rouleau A, et al. L’influence des représentations de la maladie, de la douleur et de la guérison sur le processus de réadaptation au travail des travailleurs présentant des troubles musculo-squelettiques. Longueuil: Institut de recherche Robert Sauvé en santé sécurité du travail; 2008.

Coutu MF, Baril R, Durand MJ, Côté D, Rouleau A, Cadieux G. Pain: one word with different meanings for workers during work rehabilitation. Psychol Health. submitted.

Toombs SK. The meaning of illness: a phenomenological approach to the patient-physician relationship. J Med Philos. 1987;12(3):219–40.

Turk DC, Okifuji A. Psychological factors in chronic pain: evolution and revolution. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70(3):678–90. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.70.3.678.

Michie SA, Abraham CB. Interventions to change health behaviours: evidence-based or evidence-inspired? Psychol Health. 2004;19(1):29–49. doi:10.1080/0887044031000141199.

Moss-Morris R, Petrie KJ, Weinman J. Functioning in chronic fatigue syndrome—do illness perceptions play a regulatory role? Br J Health Psychol. 1996;1(Part 1):15–25.

Coutu MF, Baril R, Durand MJ, Côté D, Rouleau A. Representations: an important key to understanding workers’ coping behaviours during rehabilitation and the return-to-work process. J Occup Rehabil. 2007;17(3):522–44. doi:10.1007/s10926-007-9089-9.

Vlaeyen JWS, Linton SJ. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Pain. 2000;85(3):317–32. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00242-0.

Vlaeyen JW, Kole-Snijders AM, Boeren RG, van Eek H. Fear of movement/(re)injury in chronic low back pain and its relation to behavioral performance. Pain. 1995;62(3):363–72. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(94)00279-N.

Fritz JM, George SZ, Delitto A. The role of fear-avoidance beliefs in acute low back pain: relationships with current and future disability and work status. Pain. 2001;94:7–15. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00333-5.

Goubert L, Crombez G, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Low back pain, disability and back pain myths in a community sample: prevalence and interrelationships. Eur J Pain. 2004;8(4):385–94. doi:10.1016/j.ejpain.2003.11.004.

Jensen MP, Karoly P. Pain-specific beliefs, perceived symptom severity, and adjustment to chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 1992;8(2):123–30. doi:10.1097/00002508-199206000-00010.

Jensen MP, Romano JM, Turner JA, Good AB, Wald LH. Patient beliefs predict patient functioning: further support for a cognitive-behavioural model of chronic pain. Pain. 1999;81(1–2):95–104. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00005-6.

Keen S, Dowell AC, Hurst K, Klaber Moffett JA, Tovey P, Williams R. Individuals with low back pain: how do they view physical activity? Fam Pract. 1999;16(1):39–45. doi:10.1093/fampra/16.1.39.

Knish S, Calder P. Beliefs of chronic low back pain sufferers: a concept map. Can J Rehabil. 1999;12(3):167–79.

van Tulder MW, Ostelo R, Vlaeyen JW, Linton SJ, Morley SJ, Assendelft WJ. Behavioral treatment for chronic low back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine. 2000;25(20):2688–99. doi:10.1097/00007632-200010150-00024.

Vowles KE, Gross RT. Work-related beliefs about injury and physical capability for work in individuals with chronic pain. Pain. 2003;101(3):291–8. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00337-8.

Waddell G, Burton AK. Concepts of rehabilitation for the management of low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2005;19(4):655–70. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2005.03.008.

Walsh DA, Radcliffe JC. Pain beliefs and perceived physical disability of patients with chronic low back pain. Pain. 2002;97:23–31. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00426-2.

Werner ELMD, Ihlebaek CP, Skouen JSMDP, Laerum EMDP. Beliefs about low back pain in the Norwegian general population: are they related to pain experiences and health professionals? [Miscellaneous Article]. Spine. 2005;30(15):1770–6. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000171909.81632.fe.

Woby SR, Watson PJ, Roach NK, Urmston M. Adjustment to chronic low back pain: the relative influence of fear-avoidance beliefs, catastrophizing, and appraisals of control. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42(7):761–74. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00195-5.

Cleary L, Thombs DL, Daniel EL, Zimmerli WH. Occupational low back disability: effective strategies for reducing lost work time. AAOHN J. 1995;43(2):87–94.

van der Giezen AM, Bouter LM, Nijhuis FJ. Prediction of return-to-work of low back pain patients sicklisted for 3–4 months. Pain. 2000;87(3):285–94. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00292-X.

Crook J, Moldofsky H, Shannon H. Determinants of disability after a work related musculetal injury. J Rheumatol. 1998;25(8):1570–7.

Hazard RG, Haugh LD, Reid S, Preble JB, MacDonald L. Early prediction of chronic disability after occupational low back injury. Spine. 1996;21(8):945–51. doi:10.1097/00007632-199604150-00008.

van der Weide WE, Verbeek J, Salle HJA, van Dijk FJH. Prognostic factors for chronic disability from acute low-back pain in occupational health care. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1999;25(1):50–6.

Buick DL. Illness representations and breast cancer: coping with radiation and chemotherapy. In: Petrie KJ, Weinman JA, editors. Perceptions of health and illness. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic; 1997. p. 379–411.

Heijmans MJ. The role of patients’ illness representations in coping and functioning with Addison’s disease. Br J Health Psychol. 1999;4(Part 2):137–49. doi:10.1348/135910799168533.

Petrie K, Moss-Morris R, Weinman J. The impact of catastrophic beliefs on functioning in chronic fatigue syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39(1):31–7. doi:10.1016/0022-3999(94)00071-C.

Petrie KJ, Weinman J, Sharpe N, Buckley J. Role of patients’ view of their illness in predicting return to work and functioning after myocardial infarction: longitudinal study. Br Med J. 1996;312(7040):1191–4.

Scharloo M, Kaptein A. Measurement of illness perceptions in patients with chronic somatic illness: a review. In: Petrie KJ, Weinman JA, editors. Perceptions of health and illness. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic; 1997. p. 103–54.

Leventhal H, Brissette I, Leventhal EA. The common sense model of self-regulation of health and illness. In: Cameron L, Leventhal H, editors. The self-regulation of health and illness behaviour. London: Routledge; 2003. p. 42–65.

Leventhal H, Meyer D, Nerenz D. The common sense representation of illness danger. In: Rachman S, editor. Contributions to medical psychology. Oxford: Pergamon Press; 1980. p. 7–30.

Baumann LJ, Cameron LD, Zimmerman RS, Leventhal H. Illness representations and matching labels with symptoms. Health Psychol. 1989;8(4):449–69. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.8.4.449.

Leventhal H, Diefenbach M. The active side of illness cognition. In: Skelton JA, Croyle RT, editors. Mental representation in health and illness. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1991. p. 247–72.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: WH Freeman; 1997.

Leventhal H, Meyer D, Gutmann M. The role of theory in the study of compliance to high blood pressure regimens. In: Haynes RB, Mattson ME, Engebretson O, editors. Patient compliance to prescribed antihypertensive medication regimens: a report to the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NIH Publication No. 81-2102). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1980.

Kleinman A. Patients and healers in the context of culture: an exploration of the borderland between anthropology, medicine, and psychiatry. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1980.

Massé R. Culture et santé publique. Boucherville: Gaëtan Morin; 1995.

Kleinman A, Seeman D. Personal experience of illness. In: Albrecht GL, Fitzpatrick R, Scrimshaw SC, editors. The handbook of social studies in health and medicine. London: Sage; 2000. p. 230–42.

Landry R, Nabil A, Lamari M. Climbing the ladder of research utilization: evidence from social science research. Sci Commun. 2001;22:396–422. doi:10.1177/1075547001022004003.

Büchi S, Sensky T. PRISM Pictorial Representation of Illness and Self Measure. Psychosomatics. 1999;40:314–20.

Williams RM, Myers AM. A new approach to measuring recovery in injured workers with acute low back pain: resumption of activities of daily living scale. Phys Ther. 1998;78(6):613–23.

Riley JF, Ahern DK, Follick MJ. Chronic pain and functional impairment: assessing beliefs about their relationship. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1988;69(8):579–82.

Symonds TL, Burton AK, Tillotson KM, Main CJ. Do attitudes and beliefs influence work loss due to low back trouble? Occup Med (Oxford). 1996;46(1):25–32.

DeGood DE, Shutty MSJ. Assessment of paine belief, coping, and self-efficacy. In: Turk DC, Melzack R, editors. Handbook of pain assessment. New York: Guilford Press; 1992. p. 214–34.

Cook AJ, DeGood DE. The cognitive risk profile for pain development of a self report inventory for identifying beliefs and attitudes that interfere with pain management. Clin J Pain. 2006;22(4):332–45. doi:10.1097/01.ajp.0000209801.78043.91.

Bosscher RJ, Smith JH. Confirmatory factor analysis of the General Self Efficacy Scale. Behav Res Ther. 1998;36:339–43. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00025-4.

Gibson L, Strong J. The reliability and validity of a measure of perceived functional capacity for work in chronic back pain. J Occup Rehabil. 1996;6(3):159–75. doi:10.1007/BF02110753.

Anderson KO, Dowds BN, Pelletz RE, Edwards WT, Peeters-Asdourian C. Development and initial validation of a scale to measure self-efficacy beliefs in patients with chronic pain. Pain. 1995;63(1):77–84. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(95)00021-J.

Levin JB, Lofland KR, Cassisi JE, Poreh AM, Blonsky ER. Back pain self-efficacy scale [BPSES]. In: Redman BKé, editor. Measurement tools in patient education. New York: Springer; 1990. p. 337–40.

Skevington SM, Skevington A. A standardised scale to measure beliefs about pain control (BPCQ): a preliminary study. Psychol Health. 1990;4:221–32. doi:10.1080/08870449008400392.

ter Kuile MM, Linssen ACG, Spinhoven P. The development of the multidimensional locus of pain control questionnaire (MLPC): factor structure, reliability, and validity. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 1993;15(4):387–404. doi:10.1007/BF00965040.

Main CJ, Waddell G. A comparison of cognitive measures in low back pain: statistical structure and clinical validity at initial assessment. Pain. 1991;46(3):287–98. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(91)90112-B.

Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale—development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7(4):524–32. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.7.4.524.

Mannion AF, Balague F, Pellise F, Cedraschi C. Pain measurement in patients with low back pain. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007;3(11):610–18. doi:10.1038/ncprheum0646.

Turk DC, Melzak R, editors. Handbook of pain assessment. New York: The Guilford Press; 2001.

Ho K, Spence J, Murphy MF. Review of pain-measurement tools. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;27(4):427–32. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(96)70223-8.

Goffman E. Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York: Aronson J; 1974.

Berger PL, Luckmann T. The social construction of reality: a treatise in the sociology of knowledge. New York: Doubleday; 1966.

Blumer, H. Symbolic interactionism. Perspective and method. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall; 1969.

Weiss M. Explanatory Model Interview Catalogue (EMIC): framework for comparative study of illness. Transcult Psychiatry. 1997;34(6):235–63. doi:10.1177/136346159703400204.

Lloyd KR, Jacob KS, Patel V, Louis L, Bhugra D, Mann AH. The development of the Short Explanatory Model Interview (SEMI) and its use among primary-care attenders with common mental disorders. Psychol Med. 1998;28(5):123–7. doi:10.1017/S0033291798007065.

Groleau D, Kirmayer LJ, Young A. The McGill Illness Narrative Interview (MINI): an interview schedule to explore different meanings and modes of reasoning related to illness experience. Transcult Psychiatry. 2006;43(3):671–91. doi:10.1177/1363461506070796.

Weiss MG, Doongaji DR, Siddhartha S, Wypij D, Pathare S, Bhatawdekar M, et al. The Explanatory Model Interview Catalogue (EMIC) Contribution to cross-cultural research methods from a study of leprosy and mental health. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;160:819–30.

Channabasavanna SM, Raguram R, Weiss MG, Parvathavardhini R, Thriveni M. Ethnography of psychiatric illness: a pilot study. Nimhans J. 1993;11(1):1–10.

Weiss MG, Raguram R, Channabasavanna SM. Cultural dimensions of psychiatric diagnosis. A comparison of DSM-III-R and illness explanatory models in south India. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;166:353–539.

Raguram R, Weiss MW, Channabasavanna SM. Stigma, somatisation and depression—a report from South India. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:1043–9.

Young A, Kirmayer LJ. Illness narrative interview protocols. Transcult Psychiatry. 1996;43(4):688.

Young A. Rational men and the explanatory model approach Culture. Med Psychiatry. 1981;5:317–35. doi:10.1007/BF00054773.

Young A. Rational men and the explanatory model approach. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1982;6:57–71. doi:10.1007/BF00049471.

Bishop GD. Understanding the understanding of illness: lay disease representations. In: Skelton JA, Croyle RT, editors. The mental representation of health and illness: models and applications. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1991. p. 32–59.

Leventhal H, Leventhal EA, Cameron L. Representations procedures and affect in illness self-regulation: a perceptual-cognitive model. In: Baum A, Revenson TA, Singer JE, editors. Handbook of health psychology. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2001. p. 19–48.

Whitley R, Kirmayer LJ, Groleau D. Understanding immigrants’ reluctance to utilize health services: a qualitative case study from Montreal. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51(4):205–9.

Whitley R, Kirmayer LJ, Groleau D. Public pressures, private protest: illness narratives of West Indian immigrants in Montreal with medically unexplained symptoms. Anthropol Med. 2006;3:193–205.

Jensen MP, Karoly P, Huger R. The development and preliminary validation of an instrument to assess patients’ attitudes toward pain. J Psychosom Res. 1987;31(3):393–400. doi:10.1016/0022-3999(87)90060-2.

Williams DA, Thorn BE. An empirical assessment of pain beliefs. Pain. 1989;36(3):351–8. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(89)90095-X.

Edwards LC, Pearce SA, Turner-Stokes L, Jones A. The pain beliefs questionnaire: an investigation of beliefs in the causes and consequences of pain. Pain. 1992;51(3):267–72.

Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, Somerville D, Main CJA. Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain. 1993;52(2):157–68. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(93)90127-B.

Turk DC, Rudy TE, Salovey P. Implicit models of illness. J Behav Med. 1986;9(5):453–74. doi:10.1007/BF00845133.

Weinman J, Petrie KJ, Moss-Morris R, Horne R. The illness perception questionnaire: a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of illness. Psychol Health. 1996;11:431–5. doi:10.1080/08870449608400270.

Moss-Morris R, Weinman J, Petrie KJ, Horne R, Cameron LD, Buick D. The revised illness perception questionnaire (IPQ-R). Psychol Health. 2002;17(1):1–16. doi:10.1080/08870440290001494.

Broadbent E, Petriea KJ, Maina J, Weinman J. The brief illness perception questionnaire. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60(6):631–7. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.10.020.

Evers AWK, Van Lankveld W, Jongen P, Jacobs J, Bijilma J. Beyond unfavorable thinking: the illness cognition questionnaire for chronic diseases. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(6):1026–36. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.69.6.1026.

Jensen IB, Nygren A, Lundin A. Cognitive-behavioural treatment for workers with chronic spinal pain: a matched and controlled cohort study in Sweden. Occup Environ Med. 1994;51(3):145–51.

Duquette J, McKinley PA, Litowski J. Traduction et pré-test du Questionnaire sur les attitudes envers la douleur (Survey of Pain Attitudes). Revue québécoise d’ergothérapie. 2001;10:23–30.

Jensen IB, Bodin L, Ljungqvist T, Bergström KG, Nygren A. Assessing the needs of patients in pain: a matter of opinion? Spine. 2000;25(21):2816–23. doi:10.1097/00007632-200011010-00015.

Bergner M, Bobbitt RA, Carter WB, Gilson BS. The sickness impact profile: development and final revision of a health status measure. Med Care. 1981;19(8):787–805. doi:10.1097/00005650-198108000-00001.

Strong J, Ashton R, Chant D. The measurement of attitudes towards and beliefs about pain. Pain. 1992;48(2):227–36. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(92)90062-G.

Herda CA, Siegeris K, Basler HD. The pain beliefs and perceptions inventory—further evidence for a 4-factor structure. Pain. 1994;57(1):85–90. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(94)90111-2.

Morley S, Wilkinson L. The pain beliefs and perceptions inventory: a British replication. Pain. 1995;61:427–33. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(94)00202-P.

Turner JA, Jensen MP, Romano JM. Do beliefs, coping, and catastrophizing independently predict functioning in patients with chronic pain? Pain. 2000;85:115–25. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00259-6.

Wallston KA, Wallston BS, DeVellis R. Development of Multidimensional Health Locus of Control (MHLC) scales. Health Educ Monogr. 1978;11:160–70.

Staerkle R, Mannion AF, Elfering A, Junge A, Semmer NK, Jacobshagen N, et al. Longitudinal validation of the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) in a Swiss-German sample of low back pain patients. Eur Spine J. 2004;13:332–40.

Lethem J, Slade PD, Troup JD, Bentley G. Outline of a fear-avoidance model of exaggerated pain perception: I. Behav Res Ther. 1983;21(4):401–8. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(83)90009-8.

Schiaffino KM, Cea CD. Assessing chronic illness representations: the Implicit Models of Illness Questionnaire. J Behav Med. 1995;18(6):531–48. doi:10.1007/BF01857894.

Jodelet D. Les représentations sociales dans le champ des sciences humaines. d’aujourd’hui S, editor. Paris: France Presses universitaires de France; 1989.

Abric J-C. La recherche du noyau central et de la zone muette des représentations sociales. In: Abric J-C, editor. Méthodes d’étude des représentations sociales. Ramonville Saint-Agne: Eres; 2003. p. 59–80.

Cooper A, Lloyd GS, Weinman J, Jackson G. Why patients do not attend cardiac rehabilitation: role of intentions and illness beliefs. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 1999;82:234–6.

Steed L, Newman SP, Hardman SMC. An examination of the self-regulation model in a trial fibrillation. Br J Health Psychol. 1999;4:337–47. doi:10.1348/135910799168687.

Murphy H, Dickens C, Creed F, Bernstein R. Depression, illness perception and coping in rheumatoid arthritis. J Psychosom Res. 1999;46:155–64. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(98)00073-7.

Pimm TJ, Weinman J. Applying Leventhal’s self-regulation model to adaptation and intervention in rheumatic disease. Clin Psychol Psychother. 1998;5:62–75. doi :10.1002/(SICI)1099-0879(199806)5:2<62::AID-CPP155>3.0.CO;2-L.

Fortune DG, Richards HL, Main CJ, Griffiths CEM. Pathological worrying, illness perceptions and disease severity in patients with psoriasis. Br J Health Psychol. 2000;5:71–82. doi:10.1348/135910700168775.

Scharloo M, Kaptein A, Weinman J, Bergman W, Vermeer BJ, Rooijmans HGM. Patients’ illness perception and coping as predictors of functional status in psoriasis: a 1-year follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:899–907. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03469.x.

Heijmans M. Coping and adaptive outcome in chronic fatigue syndrome: importance of illness cognitions. J Psychosom Res. 1998;45:39–51. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(97)00265-1.

Griva K, Myers LB, Newman S. Illness perceptions and self-efficacy beliefs in adolescents and young adults with insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. Psychol Health. 2000;15:733–50. doi:10.1080/08870440008405578.

Papadopoulos L, Bor R, Walker C, Legg C. The Illness perception questionnaire as a reliable assessment tool: cognitive representations of vitiligo. Psychol Health Med. 2001;6(4):441–6.

Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS Scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:1063–70. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063.

Buick DL, Petrie KJ. “I know just how you feel”: the validity of healthy women’s perceptions of breast-cancer patients receiving treatment. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2002;32(1):110–23. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb01422.x.

Foster NE, Bishop A, Thomas E, Main C, Horne R, Weinman J, et al. Illness perceptions of low back pain patients in primary care: what are they, do they change and are they associated with outcome? Pain. 2008;136(1–2):177–87. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2007.12.007.

Lobban F, Barrowclough C, Jones S. Assessing cognitive representations of mental health problems. II. The illness perception questionnaire for schizophrenia: relatives’ version. Br J Clin Psychol. 2005;44(2):163–79. doi:10.1348/014466504X19785.

Fortune G, Barrowclough C, Lobban F. Illness representations in depression. Br J Clin Psychol. 2004;43(4):347–64. doi:10.1348/0144665042388955.

Rankin H, Holttum SE. The relationship between acceptance and cognitive representations of pain in participants of a pain management programme. Psychol Health Med. 2003;8(3):329–34. doi:10.1080/1354850031000135768.

Kennedy T, Rehehr G, Rosenfield J, Roberts W, Lingard L. Exploring the gap between knowledge and behavior: a qualitative study of clinician action following an educational intervention. Acad Med. 2004;79(5):386–92. doi:10.1097/00001888-200405000-00006.

Carlisle AC, John AM, Fife-Schaw C, Lloyd M. The self-regulatory model in women with rheumatoid arthritis: relationships between illness representations, coping strategies, and illness outcome. Br J Health Psychol. 2005;10:571–87. doi:10.1348/135910705X52309.

Jessop D, Rutter DR. Adherence to asthma medication: the role of illness representations. Psychol Health. 2003;18(5):595–612. doi:10.1080/0887044031000097009.

Vaughan R, Morrison L, Miller E. The illness representations of multiple sclerosis and their relations to outcome. Br J Health Psychol. 2003;8:287–301. doi:10.1348/135910703322370860.

Hagger MS, Orbell S. A meta-analytic review of the common-sense model of illness representations. Psychol Health. 2003;18(2):141–84. doi:10.1080/088704403100081321.

Leventhal H, Nerenz DR, Steele DJ. Illness representation and coping with health threats. In: Baum A, Taylor SE, Singer JE, editors. Handbook of psychology and health Hillsdale. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1984. p. 219–52.

Beck JS. Cognitive therapy: basics and beyond. New York: Guilford Press; 1995.

Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Basic Books; 1979.

Beck AT, Emery G. Anxiety disorders and phobias: a cognitive perspective. New York: Basic Books; 1985.

Goffman E. Stigma. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall; 1963.

Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM. Changes after multidisciplinary pain treatment in patient pain beliefs and coping are associated with concurrent changes in patient functioning. Pain. 2007;131:38–47. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.007.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the Institut de recherche Robert-Sauvé en santé et en sécurité au travail (IRSST) and by the Research Chair in Work Rehabilitation (Foundation J. Armand Bombardier and Pratt & Whitney Canada).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Coutu, MF., Durand, MJ., Baril, R. et al. A Review of Assessment Tools of Illness Representations: Are These Adapted for a Work Disability Prevention Context?. J Occup Rehabil 18, 347–361 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-008-9148-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-008-9148-x