Abstract

An appraisal of Paleogene floral and land mammal faunal dynamics in South America suggests that both biotic elements responded at rate and extent generally comparable to that portrayed by the global climate pattern of the interval. A major difference in the South American record is the initial as well as subsequent much greater diversity of both Neotropical and Austral floras relative to North American counterparts. Conversely, the concurrent mammal faunas in South America did not match, much less exceed, the diversity seen to the north. It appears unlikely that this difference is solely due to the virtual absence of immigrants subsequent to the initial dispersal of mammals to South America, and cannot be explained solely by the different collecting histories of the two regions. Possible roles played by non-mammalian vertebrates in niche exploitation remain to be explored.

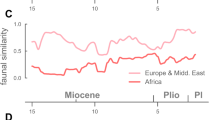

The Paleogene floras of Patagonia and Chile show a climatic pattern that approximates that of North America, with an increase in both Mean Annual Temperature (MAT) and Mean Annual Precipitation (MAP) from the Paleocene into the Early Eocene Climatic Optimum (EECO), although the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) is not recognized in the available data set. Post-EECO temperatures declined in both regions, but more so in the north than the south, which also retained a higher rate of precipitation.

The South American Paleogene mammal faunas developed gradual, but distinct, changes in composition and diversity as the EECO was approached, but actually declined somewhat during its peak, contrary to the record in North America. At about 40 Ma, a post-EECO decline was recovered in both hemispheres, but the South American record achieved its greatest diversity then, rather than at the peak of the EECO as in the north. This post-EECO faunal turnover apparently was a response to the changing conditions when global climate was deteriorating toward the Oligocene. Under the progressively more temperate to seasonally arid conditions in South America, this turnover reflected a major change from the more archaic, and more tropical to subtropical-adapted mammals, to the beginning of the ultimately modern South American fauna, achieved completely by the Eocene-Oligocene transition. Interestingly, hypsodonty was achieved by South American cursorial mammals about 15–20 m.y. earlier than in North America. In addition to being composed of essentially different groups of mammals, those of the South American continent seem to have responded to the climatic changes associated with the ECCO and subsequent conditions in a pattern that was initially comparable to, but subsequently different from, their North American counterparts.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Abello MA (2007) Sistemática y bioestratigrafía de los Paucituberculata (Mammalia, Marsupialia) del Cenozoico de América del Sur. Unpublished PhD thesis, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata, 381 pp

Adelmann D (2001) Känozoische Bedeckenwicklung in der südlichen Puna am Beispiel des Salar de Antofalla (NW-Argentinien). Unpublished PhD thesis, Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin, 180 pp

Albino AM (2000) New record of snakes from the Cretaceous of Patagonia (Argentina). Geodiversitas 22:247–253

Albright LB, Woodburne MO, Fremd TJ, Swisher CC III, MacFadden BJ, Scott GR (2008) Revised chronostratigraphy and biostratigraphy of the John Day Formation (Turtle Cove and Kimberly Members), Oregon, with implications for updated calibration of the Arikareean North American Land Mammal Age. J Geol 116:211–237

Ameghino F (1906) Les formtions sédimentaires du Crétacé superieur et du Tertiare de Patagonie avec un paralléle entre leurs faunes mammalogiques et celles de l’ancien continent. Anal Mus Nac Hist Nat 15:1–568

Andreis RR (1977) Geología del área de Cañadón Hondo, Departamento Escalante, Provincia del Chubut, República Argentina. Obra Centenario Mus La Plata 4:77–102

Andreis RR, Mazzoni MM, Spalletti LS (1975) Estudio estratigráfico y paleoambiental de las sedimentitas teriarias entre Pico Salamanca y Bahía Bustamante, Provincia de Chubut, República Argentina. Rev Asoc Geol Argent 30:85–103

Antoine P-O, Marivaux L, Croft DA, Billet G, Ganerød M, Jaramillo C, Martin T, Orliac MJ, Tejada J, Altamirano AJ, Duranthon F, Fanjat G, Rousse S, Salas Gismondi R (2011) Middle Eocene rodents from Peruvian Amazonia reveal the pattern and timing of caviomorph origins and biogeography. Proc R Soc B, pub online 12 October 2011; electronic suppl. material: 10.1098/rspb.2011.1732

Aragón E, Goin FJ, Aguilera YE, Woodburne MO, Carlini AA, Roggiero MF (2011) Palaeogeography and palaeoenvironments of northern Patagonia from the Late Cretaceous to the Miocene: the Palaeogene Andean gap and the rise of the North Patagonian High Plateau. Biol J Linn Soc 103(2):305–315

Archangelsky S (1973) Palinología del Paleoceno de Chubut I. Descripciones sistemáticas. Ameghiniana 10:339–399

Archangelsky S, Barreda V, Passalia MG, Gandolfo MA, Prámparo M, Romero E, Cúneo R, Zamuner A, Iglesias A, Llorens M, Puebla GG, Quattrocchio M, Volkheimer W (2009) Early angiosperm diversification: evidence from southern South America. Cretaceous Res 30:1073–1082

Arriagada C, Cobbold PR, Roperch P (2006a) Salar de Atacama basin: a record of compressional tectonics in the central Andes since the mid-Cretaceous. Tectonics 25, TC1008; doi:10.1029/2004TC001770; 2006, 19 pp

Arriagada C, Roperch P, Mpodozis C, Fernandez R (2006b) Paleomagmatism and tectonics of the southern Atacama Desert (25–28°), northern Chile. Tectonics 25, TC4001, doi:10.1029/2005TC001923, 26 pp

Artabe AE, Zamuner AB, Stevenson DW (2004) Two new petrified Cycads stems, Brunoa gen. nov. and Worsdellia gen. nov., from the Cretaceous of Patagonia (Bajo de Santa Rosa, Río Negro Province), Argentina. Bot Rev 70:121–133

Askin RA, Spicer RA (1995) The Late Cretaceous and Cenozoic history of vegetation and climate at northern and southern high latitudes: a comparison. In: National Research Council (eds) Effects of Past Global Change on Life. National Academy Press, Washington, DC, pp 156–173

Baldoni AM, Askin RA (1993) Palynology of the lower Lefipán Formation (Upper Cretaceous) of Barranca de los Perros, Chubut Province, Argentina. Part II. Angiosperm pollen and discussion. Palynology 17:241–264

Barreda V, Palazzesi L (2007) Patagonian vegetation turnovers during the Paleocene-Early Neogene: origin of arid-adapted floras. Bot Rev 73(1):31–50

Barreda V, Palazzesi L (2010) Vegetation during the Eocene—Miocene interval in central Patagonia: a context of mammal evolution. In: Madden RH, Carlini AA, Vucetich MG, Kay RF (eds) The Paleontology of Gran Barranca. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 375–382

Barreda VD, Palazzesi L, Telleria MC, Katinas L, Crisci JV, Bremer K, Passalia MG, Corsolini R, Brizuela RR, Bechis F (2010) Eocene Patagonia fossils of the daisy family. Science 329:1621

Beck RMD (2012) An ‘ameridelphian’ marsupial from the early Eocene of Australia supports a complex model of Southern Hemisphere marsupial biogeography. Naturwissenschaften 99:715–729

Bellosi ES, González MG (2010) Paleosols of the middle Cenozoic Sarmiento Formation, central Patagonia. In: Madden RH, Carlini AA, Vucetich MG, Kay RF (eds) The Paleontology of Gran Barranca. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 293–305

Bellosi ES, Madden, RH (2005) Estratigrafia fisica preliminar de las secuencias piroclastics terrestres de la Formacion Sarmiento (Eoceno-Mioceno) en la Gran Barranca, Chubut. Actas del XVI Congreso Geológico Argentino, La Plata, Tomo IV:427–432

Bergqvist LP, Powell JE, Avilla LS (2004) A new xenungulate from the Río Loro Formation (Paleocene) from Tucumán province (Argentina). Ameghiniana Supl 41(4):36R

Bernaola G, Baceta JI, Orue-Etxebarria X, Alegret L, Martín-Rubio M, Arosteguji J, Dinarès-Turell J (2007) Evidence of an abrupt environmental disruption during the mid-Paleocene biotic event (Zumaia section, western Pyrenees). Geol Soc Am Bull 119(7/8):785–795

Berry EW (1925) A Miocene flora from Patagonia. Johns Hopkins University Studies in Geology 6:183–251

Berry EW (1938) Tertiary flora from the Río Pichileufú, Argentina. Geol Soc Am Spec Pap 12:1–149

Bertels A (1975a) Biostratigrafia del Paleogeno en la Republica Argentina. Rev Espanol Micropaleontol, Madrid, 7 (3):429–450

Bertels A (1975b) Bioestratigrafía del Paleoceno marino en la provincia del Chubut, República Argentina.” 1° Congreso Argentino de Paleontología y Bioestratigrafía (Tucumán, 1974), Actas 2: 271–316

Bertini RJ, Marshall LG, Brito P (1993) Vertebrate faunas from the Adamantina and Marilia formations (Upper Bauru Group, Late Cretaceous, Brazil) in their stratigraphic and paleobiogeographic context. N Jb Geol Paläontol Abh 188(1):71–101

Bertrand OC, Flynn JJ, Croft DA, Wyss AR (2012) Two new taxa (Caviomorpha, Rodentia) from the early Oligocene Tinguiririca fauna (Chile). Am Mus Novitates 3750:1–36

Billet G, Hautier L, Muizon C de, Valentin X (2011) Oldest cingulate skulls provide congruence between morphological and molecular scenarios of armadillo evolution. Proc R Soc B 278:2791–2797

Bona P (2005) Sistemática y biogeografía de las tortugas y los crocodilos Paleocenos de la Formación Salamanca, provincia de Chubut, Argentina. Unpublished PhD thesis. Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata, 186 pp

Bonaparte JF (1986) Sobre Mesungulatum houssayi y nuevos mamíferos cretácicos de Patagonia. Actas IV Cong Argent Paleontol Bioestrat 2:48–61

Bonaparte JF (1987) The Late Cretaceous fauna of Los Alamitos, Patagonia, Argentina. Rev Mus Argent Cienc Nat “Bernardino Rivadavia.” Institut Nac Investig Cienc Natl: Paleontol 3(3):103–178

Bonaparte JF (1990) New Late Cretaceous mammals from the Los Alamitos Formation, northern Patagonia. Natl Geog Res 6:63–93

Bonaparte JF, Soria MF (1985) Nota sobre el primer mamífero del Cretácico Argentino, Campaniano-Maastrichtiano (Condylarthra). Ameghiniana 21:177–183

Bonaparte JF, Van Valen L, Kramarz A (1993) La fauna local de Punta Peligro. Paleoceno inferior de la provincia de Chubut, Patagonia, Argentina. Evol Monogr 14:1–61

Bond M, Carlini AA, Goin FJ, Legarreta L, Ortiz-Jaureguizar E, Pascual R, Uliana MA (1995) Episodes in South American land mammal evolution and sedimentation: testing their apparent concurrence in a Palaeocene succession from central Patagonia. VI Cong Argent Paleontol Bioestrat Actas:47–58

Bond M, Deschamps CM (2010) The Mustersan age at Gran Barranca: a review. In: Madden RH, Carlini AA, Vucetich MG, Kay RF (eds) The Paleontology of Gran Barranca. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 255–263

Bond M, Kramarz A, MacPhee RDE, Reguero M (2011) A new astrapothere (Mammalia, Meridiungulata) from La Meseta Formation, Seymour Marambio) Island, and a reassessment of previous records of Antarctic astrapotheres. Am Mus Novitates 3718:1–16

Bond M, López GM (1993) El primer Notohippidae (Mammalia, Notoungulata) de la Formación Lumbrera (Grupo Salta) del Noroeste Argentino: consideraciones sobre la sistemática le la Familia Notohippidae. Ameghiniana 30(1):59–68

Bond M, López GM (1995) Los Mamíferos da la Formación Casa Grande de La Provincia de Jujuy, Argentina. Ameghiniana 32(3):301–309

Bond M, Vucetich MG (1983) Indalecia grandesis gen. et sp. nov. del Eoceno temprano del Noroeste Argentino, tipo de una nueva subfamilia de los Adianthidae (Mammalia, Litopterna). Rev Asoc Geol Argent 37:107–117

Boyde A, Fortelius M (1986) Development, structure and function of rhinoceros enamel. Zool J Linn Soc 87:181–214

Brea M, Matheos SD, Raigemborn MS, Iglesias A, Zucol AF, Prámparo M (2011) Paleoecology and paleoenvironments of Podocarp trees in the Ameghino Petrified forest (Golfo San Jorge Basin, Patagonia, Argentina): constraints for early Paleogene paleoclimate. Geol Acta 9(1):1–23

Brea M, Matheos S, Zamuner A, Ganuza D (2005) Análisis de los anillos de crecimiento del bosque fósil de Víctor Szlápelis, Terciario inferior del Chubut, Argentina. Ameghiniana 42(2):407–418

Brea M, Zamuner AB, Matheos SD, Iglesias A, Zucol AF (2008a) Fossil wood of the Mimosoideae from the early Paleocene of Patagonia, Argentina. Alcheringa 32:431–445

Brea M, Zucol AF, Raigemborn MS, Matheos S (2008b) Reconstruction of past vegetation through phytolith analysis of sediments from the upper Paleocene—Eocene? (Las Flores Formation), Chubut, Argentina. In: Korstanje MA Babot M. del P (eds) Matices interdisciplinarios en estudios fitoliticos y otros microfósiles. BAR Internat Ser S1870(9), pp 91–108

Candeiro CRA, Martinelli AG, Avila LS, Rich TH (2006) Tetrapods from the Upper Cretaceous (Turonian – Maastrichtian) Baru Group of Brazil: a reappraisal. Cretaceous Res 27:923–946

Carlini AA, Ciancio M, Scillato-Yané GJ (2005) Los Xenarthra de Gran Barranca: más 20 Ma de historia. Actas del XVI Congreso Geológico Argentino, La Plata, Tomo IV: 419–424

Carlini AA, Ciancio, M., Scillato-Yané GJ (2010) Middle Eocene - early Miocene Dasypodidae (Xenarthra) of southern South America: faunal succession at Gran Barranca - biostratigraphy and paleoecology. In: Madden RH, Carlini AA, Vucetich MG, Kay RF (eds) The Paleontology of Gran Barranca. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 106–129

Carlini AA, Scillato-Yané GJ (1999) Cingulata del Oligoceno tardio de Salla Bolivia. Resúmenes del Congreso Internacional Evolución Neotropical del Cenozoico:15

Carlini AA, Scillato-Yané GJ (2004) The oldest Megalonychidae (Tardigrada, Xenarthra) and the phylogenetic relationships of the family. N Jb Geol Paläontol Abh 233:423–443

Carlini AA, Scillato-Yané GJ, Vizcaíno SF (1990) Un singular Paratheria del Eoceno temprano de Patagonia, Argentina. VII Jornad Argent Paleontol Verteb, Buenos Aires, 1990. Ameghiniana 26(3–4):241

Carrapa B, Adelmann D, Hilley GE, Mortimer E, Sobel ER, Strecker MR (2005) Oligocene range uplift and development of plateau morphology in the southern central Andes. Tectonics 24, TC4011, doi:10.1029/2004TC001762, 19 pp

Casadio S, Griffin M, Parras A (2005) Camptonectes and Plicatula (Bivalvia, Pteriomorphia) from the Upper Maastrichtian of northern Patagonia: palaeobiogeographic implications. Cretaceous Res 26:507–524

Case JA, Goin F, Woodburne MO (2005) ‘South American’ marsupials from the Late Cretaceous of North America and the origin of marsupial cohorts. J Mammal Evol 12(3/4):461–494

Chimento NR, Agnolin FL, Novas FE (2012) The Patagonian fossil mammal Necrolestes: a Neogene survivor of Dryolestoidea. Rev Mus Argentino Cienc Nat ns 14(2):000–000

Chornogubsky L (2010) Sistemática de familia Polydolopidae (Mammalia, Marsupialia, Polydolopimorphia) de América del Sur y la Antártica. Unpublished PhD thesis. Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, 352 pp

Christophel DC (1995) The impact of climatic changes on the development of the Australian flora. In: National Research Council (eds) Effects of Past Global Change on Life. National Academy Press, Washington, DC, pp 156–173

Cifelli RL (1985) Biostratigraphy of the Casamayoran, early Eocene, of Patagonia. Am Mus Novitates 2820:1–26

Cione AL, Gouiric-Cavalli S, Gelfo JN, Goin FJ (2011) The youngest non-lepidosirenid lungfish of South America (Dipnoi, latest Paleocene – earliest Eocene, Argentina). Alcheringa 35:193–198

Cladera G, Ruigómez D, Ortiz-Jaureguizar E, Bond M, López G (2004) Tafonomía de la Gran Hondonada (Formación Sarmiento, Edad-mamífero Mustersense, Eoceno Medio) Chubut, Argentina. Ameghiniana 41(3):315–330

Clemens WA (1966) Fossil mammals of the type Lance Formation, Wyoming. Part II. Marsupialia. Univ Calif Publ Geol Sci 61:1–122

Contreras C, Jaillard E, Paz M (1996) Subsidence history of the north Peruvian Oriente (Marañon Basin) since the Cretaceous. 3rd ISAG, St Marlo 17–19/00:327–330

Correa E, Jaramillo C, Manchester S, Gutierrez M (2010) A fruit and leaves of Rhamnaceous affinities from the Late Cretaceous (Maastridchtian) of Colombia. Am J Bot 97(1):71–79

Coster P, Benammi M, Lazzari V, Billet G, Martin T, Salem M, Bilal AA, Chaimanee Y, Schuster M, Valentin X, Brunet M, Jaeger J-J (2010) Gaudeamus lavocati sp. nov. (Rodentia, Hystricognathi) from the early Oligocene of Zallah, Libya: first African caviomorph? Naturwissenschaften 97:697–706

Crisci JV, Cigliano MM, Morrone JJ, Roig-Juñent S (1991) Historical biogeography of southern South America. Syst Zool 40:152–171

Croft DA (2006) Do marsupials make good predators? Insights from predator-prey diveristy ratios. Evol Biol Res 8:1193–1214

Croft DA, Charrier R, Flynn JJ, Wyss A (2008a) Recent additions to knowledge of Tertiary mammals from the Chilean Andes. I Simposia – Paleontol Chile, Libro Actas:91–96

Croft DA, Flynn JJ, Wyss AR (2008b) The Tinguiririca fauna of Chile and the early stages of “modernization” of South American mammal faunas. Arquivos Mus Nac, Río de Janeiro 66(1):191–211

Cúneo RN, Johnson K, Wilf P, Gandolfo MA, Iglesias A (2007) A preliminary report on the diversity of latest Cretaceous floras from northern Patagonia. Geological Society America Annual Meeting and Exposition, Denver, Colorado Abstacts with Program:584–585

Damuth J, Janis C (2011) On the relationship between hypsodonty and feeding ecology in ungulate mammals, and its utility in paleoecology. Biol Rev 86:733–758

Davis SD, Heywood VH, Herrera MacBryde O, Hamilton AC (1997) Centres of Plant Diversity: A Guide and Strategy for Their Conservation. Vol. 3. The Americas. World Wide Fund for Nature, London, 562 pp

Deeken A, Sobel ER, Coutand I, Haschke M, Riller U, Strecker MR (2006) Development of the southern Eastern Cordillera, NW Argentina, constrained by apatite fission track thermochronology: From early Cretaceous extension to middle Miocene shortening. Tectonics 25, TC6003, doi:10.1029/2005TC001894, 21 pp

Del Papa CE (2006) Stratigraphy and paleoenvironments of the Lumbrera Formation, Salta Group, northwestern Argentina. Rev Asoc Geol Argent 61:313–327.

Del Papa C, Kirschbaum A, Powell J, Brod A, Hongn F, Pimentel M (2010) Sedimentological, geochemical and paleontological insights applied to continental omission surfaces: A new approach for reconstructing an Eocene foreland basin in NW Argentina. J So Am Earth Sci 29:327–345

Deraco MV, Powell JE, López GM (2008) Primer leontinido (Mammalia, Notoungulata) de la Formación Lumbrera (Subgrupo Santa Bárbara, Grupo Salta-Paleógeno) del Noroeste Argentino. Ameghiniana 45(1):93–91

Dingle RV, Lavelle M (1998) Late Cretaceous - Cenozoic climatic variations of the northern Antarctic Peninsula: new geochemical evidence and review. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 141:215–232

Dingle RV, Marenssi SA, Lavelle M (1998) High latitude Eocene climate deterioration: evidence from the northern Antarctic Peninsula. J So Am Earth Sci 11:571–579

Doria G, Jaramillo CA, Herrera F (2008) Menispermaceae from the Cerrejón Formation, middle to late Paleocene, Colombia. Am J Bot 95(8):954–973

Dunai TJ, González López GA, Juez-Larré J (2005) Oligocene-Miocene age of aridity in the Atacama Desert revealed by exposure dating of erosion-sensitive landforms. Geology 33(4):321–324

Elgueta S, McDonough M, Le Roux J, Urqueta E, Duhart P (2000) Estratigrafía y sedimentología de las cuencas terciarias de la Región de Los Lagos (39–41°30'S). Bol Subdirección Nac Geol 57:1–50

Elissamburu A (2012) Estimación de la masa corporal en géneros del Orden Notoungulata. Estud Geol 68(1): doi:10.3989/egeol.40336.133

Escalona A, Mann P (2011) Tectonics, basin subsidence mechanisms, and paleogeography of the Caribbean-South American plate boundary zone. Marine Petroleum Geol 28:8–39

Feruglio E (1949) Descripción geológica de la Patagonia. Yacimientos Petroliferos Fisdcales. Tomo 2, Buenos Aires, 349 pp

Figueirido B, Janis CM, Pérez-Claros JA, De Renzi M, Palmqvist P (2012) Cenozoic climate change influences mammalian evolutionary dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109(3):722–727

Flynn JJ, Novacek MJ, Dodson HE, Frassinetti D, McKenna MC, Norell MA, Sears KE, Swisher CC III, Wyss AR (2002) A new fossil mammal assemblage frm the southern Chilean Andes: implications for geology, geochronology, and tectonics. J So Am Earth Sci 15: 285–302

Flynn JJ, Swisher CC III (1995) Cenozoic South American land mammal ages: correlation to global geochronologies. In: Berggren WA, Kent DV, Aubry M-P, Hardenbol J (eds) Geochronology, Time-scales and Global Stratigraphic Correlation: A Unified Framework for an Historical Geology. Soc Strat Geol Spec Pub 54:317–333

Flynn JJ, Wyss AR, Croft DA, Charrier R (2003) The Tinguiririca Fauna, Chile: biochronology, paleoecology, biogeography, and a new earliest Oligocene South American Land Mammal Age. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 195:229–259

Folguera A, Orts D, Spagnuolo M, Vera ER, Litvak V, Sagripanti L, Ramos ME, Ramos VA (2011) A review of Late Cretaceous to Quaternary palaeogeography of the southern Andes. Biol J Linn Soc 103(2):250–268

Forasiepi AM (2009) Osteology of Arctodictis sinclairi (Mammalia, Metatheria, Sparassodonta) and phylogeny of Cenozoic metatherian carnivores from South America. Monogr Mus Argent Cienc Nat, n s 6:1–174

Gandolfo MA, Cúneo RN (2005) Fossil Nelumbonaceae from the La Colonia Formation (Campanian–Maastrichtian, Upper Cretaceous), Chubut, Patagonia, Argentina. Rev Paleobot Palynology 133:169–178

Gandolfo MA, Hermsen EJ, Zamaloa MC, Nixon KC, González CC, Wilf P, Cúneo R, Johnson KR (2011) Oldest known Eucalyptus macrofossils are from South America. PloS One 6(6):e21084

García-López DA, Powell JE (2009) Un nuevo Oldfieldthomasiidae (Mammalia: Notoungulata) del Paleógeno da la provincia de Salta, Argentina. Ameghiniana 46(1):153–164

Garzione CN, Molnar P, Libarkin JC, MacFadden BJ (2006) Rapid late Miocene rise of the Bolivian Altiplano: evidence for removal of mantle lithosphere. Earth Planet Sci Let 241:543–556

Gasparini Z (1984) New Tertiary Sebecosuchia (Crocodilia: Mesosuchia) from Argentina. J Vertebr Paleontol 4:85–95

Gasparini Z, De La Fuente M (2000) Tortugas y plesiosaurios de la Formación La Colonia (Cretácico Superior) de Patagonia, Argentina. Rev Esp Paleontol 15:23–35

Gayet M, Marshall LG, Sempere T (1991) The Mesozoic and Paleocene vertebrates of Bolivia and their stratigraphic context: a review. In: Suarez-Coruco R (ed) Fosiles y facies de Bolivia - Vol. 1. Vertebrados. Rev Técnica YPFB 12(3–4):393–433

Gayó E, Hinojosa LF, Villagrán C (2005) On the persistence of Tropical Paleofloras in cental Chile during the early Eocene. Rev Palaeobot Palynology 137:41–50

Gelfo JN (2004) A new South American mioclaenid (Mammalia: Ungulatomorpha) from the Tertiary of Patagonia, Argentina. Ameghiniana 41(3):475–484

Gelfo JN (2010) The ‘condylarth’ Didolodontidae from Gran Barranca: history of the bunodont South American mammals up to the Eocene-Oligocene transition. In: Madden RH, Carlini AA, Vucetich MG, Kay RF (eds) The Paleontology of Gran Barranca. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 130–142

Gelfo JN, Goin FJ, Woodburne MO, Muizon C de (2009) Biochronological relationships of the earliest South American Paleogene mammalian faunas. Palaeontology 52(1):251–269

Gelfo JN, López GM, Bond M (2008) A new Xenungulata (Mammalia) from the Paleocene of Patagonia. J Paleontol 82(2):329–335

Gelfo JN, Sigé B (2011) A new didolodontid mammal from the late Paleocene-earliest Eocene of Laguna Umayo, Peru. Acta Palaeontol Pol 56(4):665–678

Gelfo JN, Tejedor MF (2007) The diversity of bunodont ungulates during the early Eocene in central – western Patagonia, Argentina. J Vertebr Paleontol 27(3):80A

Gingerich PD (2003) Mammalian responses to climate change at the Paleocene-Eocene boundary: Polecat Bench record in the northern Bighorn Basin, Wyoming. In: Wing SL, Gingerich PD, Schmintz W, Thomas E (eds) Causes and Consequences of Globally Warm Climates in the Early Paleogene. Boulder, Geol Soc Am Spec Pap 369:463-478

Goin FJ (2006) A review of the Caroloameghiniidae, Paleogene South America “primate-like” marsupials (?Didelphimorphia, Peradectoidea). In: Kalthoff D, Martin T, Möors T (eds) Festband für Herrn Professor Wighart v. Koenigswald anlässlich seines 65 Geburtstages. Palaeontographica Abt A, 278:57–67

Goin FJ, Abello MA (2013) Los Metatheria sudamericanos de comienzos del Neógeno (Mioceno temprano, Edad-mamífero Colhuehuapense). Parte 2: Microbiotheria y Polydolopimorphia. Ameghiniana. 00:00-00. In press

Goin FJ, Abello MA, Chornogubsky L (2010) Middle Tertiary marsupials from central Patagonia (early Oligocene of Gran Barranca): understanding South America’s Grande Coupure. In: Madden RH, Carlini AA, Vucetich MG, Kay RF (eds) The Paleontology of Gran Barranca. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 69–105

Goin FJ, Candela AM, Abello A, Oliveira EO (2009) Earliest South American paucituberculatans and their significance in understanding of “pseudodiprotodont” marsupial radiations. Zool J Linn Soc 155:867–884

Goin FJ, Candela A, López G (1998a) Middle Eocene marsupials from Antofagasta de la Sierra, northwestern Argentina. Geobios 31(1):75–85

Goin FJ, Gelfo JN, Chornogubsky L, Woodburne MO, Martin T (2012a) Origins, radiations, and distribution of South American mammals: from greenhouse to icehouse worlds. In: Patterson BD, Costa LP (eds) Bones, Clones, and Biomes: An 80-million Year History of Recent Neotropical Mammals. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 20–50

Goin FJ, Oliveira EV, Candela AM (1998b) Carolocoutoia ferigoloi n. gen. et sp. (Protodidelphidae), a new Paleocene “opossum-like” marsupial from Brazil. Palaeovertebrata 27 (3–4):145–154

Goin FJ, Pascual R, Tejedor MF, Gelfo JN, Woodburne MO, Case JA, Reguero MA, Bond M, López G, Cione AL, Udrizar Sauthier D, Balarino L, Scasso RB, Medina FA, Ubaldon MC (2006a) The earliest Tertiary therian mammal from South America. J Vertebr Paleontol 26(2):505–510

Goin FJ, Reguero MA, Pascual R, Koenigswald W von, Woodburne M.O, Case JA, Marenssi, SA, Vieytes EC, Vizcaíno SF (2006b) First Gondwanatherian mammal from Antarctica. In: Francis JE, Pirrie D, Crame JA (eds) Cretaceous-Tertiary High-Latitude Paleoenvironments, James Ross Basin, Antarctica. Spec Pub Geol Soc London, pp 145–161

Goin FJ, Tejedor MF, Chornogubsky L, López GM, Gelfo JN, Bond M, Woodburne MO, Gurovich, Y, Reguero M (2012b) Persistence of a Mesozoic, non-therian mammalian lineage in the mid-Paleogene of Patagonia. Naturwissenschaften 99:449–463

Goin FJ, Vieytes EC, Vucetich MG, Carlini AA, Bond M (2004) Enigmatic Mammal from the Paleogene of Perú. In: Campbell KE Jr (ed) The Paleogene Mammalian Fauna of Santa Rosa, Amazonian Perú. Natl Hist Mus LA County, Sci Ser 40:145–153

Goin F, Zimicz N, Forasiepi AM, Chornogubsky LC, Abello MA (2013) The rise & fall of South American metatherians: contexts, adaptations, radiations, and extinctions. In: Rosenberger AL, Tejedor MF (eds) Origins and Evolution of Cenozoic South American Mammals. Springer, New York. In press

Gomes Sant’Anna L, Riccomini C (2001) Cimentação hidrothermal em depósitos sedimentares Paleogênicos do rift continental do sudeste do Brasil: mineralogia e relaçöes tectônicas. Rev Brasil Geociênc 31(2):231–240

Gómez-Navarro C, Jaramillo C, Herrera F, Wing SL, Callejas R (2009) Palms (Arecaceae) from a Paleocene rainforest of northern Colombia. Am J Bot 96(7):1300–1312

González CC, Gandolfo MA, Zamaloa MC, Cúneo NR, Wilf P, Johnson KR (2007) Revision of the Proteaceae Macrofossil Record from Patagonia, Argentina. Bot Rev 73(3):235–266

Gradstein F, Ogg J, Smith A (eds) 2004. A Geologic Time Scale. Cambridge University Press, New York

Graham A (1999) Late Cretaceous and Cenozoic History of North American Vegetation. Oxford Univeristy Press, Oxford

Hahn G, Hahn R (2003) New multituberculate teeth from the Early Cretaceous of Morocco. Acta Palaeontol Pol 48:349–356

Hartley AJ, Evenstar L (2010) Cenozoic stratigraphic development in the north Chilean forearc: implications for basin development and uplift history of the Central Andean margin. Tectonophys 495:62–77.

Head JJ, Bloch JI, Hastings AK, Rourque JR, Cadena EA, Herrera FA, Polly PD, Jaramillo CA (2009) Giant boid snake from the Palaeocene neotropics reveals hotter past equatioral temperatures. Nature 457:715–718

Hechem J, Strelkov E (2002) Secuencia sedimentaria mesozoica del Golfo San Jorge. In: Haller M (ed) Geología y Recursos Naturales de Santa Cruz. Relatorio XV Cong Geol Argent El Calafate I Buenos Aires:129–147

Herrera FA, Jaramillo CA, Dilcher DL, Wing SL, Gómez-N C (2008) Fossil Araceae from a Paleocene Neotropical rainforest in Colombia. Am J Bot 95(12):1569–1583

Herrera FA, Manchester SR, Hoot SB, Wefferling KL, Carvalho MR, Jaramillo CA (2011) Phytogeographic implications of fossil endocarps of Menispermaceae from the Paleocene of Colombia. Am J Bot 98:2004–2007

Heywood, V. (ed) (1993) Flowering Plants of the World. Oxford University Press, New York

Hinojosa LF (2005) Cambios climáticos y vegetacionales inferidos a partir de paleofloras cenozoicas del sur de Sudamérica. Rev Geol Chile 32: 95–115

Hinojosa LF, Pesce O, Yabe A, Uemura K, Nishida H (2006) Physiognomical analysis and paleoclimate of the Ligorio Márquez Formation, 46°45'S, Chile. In: Nishida H (ed) Post-Cretaceous Floristic Changes in Southern Patagonia, Chile. Chuo University, Tokyo, pp 45–55

Hitz RB, Flynn JJ, Wyss AR (2006) New basal Interatheriidae (Typotheria, Notoungulata, Mammalia) from the Paleogene of Central Chile. Am Mus Novitates 3520:1–32

Holdridge LR (1967) Life Zone Ecology. Tropical Science Center, San Jose, Costa Rica, 206 pp

Horovitz I, Martin T, Bloch J, Ladevèze S, Kurz C, Sánchez-Villagra MR (2009) Cranial anatomy of the earliest marsupials and the origin of opossums. PLoS One 4(12):e8278

Horton BK (2005) Revised deformation history of the Central Andes: Inferences from Cenozoic foredeep and intermontane basins of the Eastern Cordillera, Bolivia. Tectonics 24, TC3011, doi:10.1029/2003TC0016919, 2005

Hungerbühler D, Steinmann M, Winkler W, Seward D, Egüez A, Peterson DE, Helg U, Hammer C (2002) Neogene stratigraphy and Andean geodynamics of southern Ecuador. Earth-Sci Rev 57:75–124

Iglesias A, Artabe AE, Morel EM (2011) The evolution of Patagonian climate and vegetation from the Mesozoic to the present. Biol J Linn Soc 103(2):409–422

Iglesias A, Wilf P, Johnson KR, Zamuner AB, Cuńeo NR, Matheos SD (2007a) A Paleocene lowland macroflora from Patagonia reveals significantly greater richness than North American analogs. Geology 35(10):947–950

Iglesias A, Wilf P, Johnson KR, Zamuner AB, Matheos SD, Cúneo RN (2007b) Rediscovery of Paleocene macrofloras in central Patagonia, Argentina. Geological Society America Annual Meeting and Exposition, Denver, Colorado Abstracts with Program:585

Iglesias A, Zamuner AB, Poiré DG, Larriestra F (2007c) Diversity, taphonomy and palaeoecology of an angiosperm flora from the Cretaceous (Cenomanian-Coniacian) in southern Patagonia, Argentina. Palaeontology 50(2):445–466

Ivany LC, Lohmann KC, Hasiuk F, Blake DB, Glass A, Aronson RB, Moody RM (2008) Eocene climate record of a high southern latitude continental shelf: Seymour Island, Antarctica. Geol Soc Am Bull 120 (5/6):659–678

Jaillard E, Bengston P, Dhondt AV (2005) Late Cretaceous marine transgressions in Ecuador and northern Peru: A refined stratigraphic framework. J So Am Earth Sci 19:307–323

Jaillard E, Bengston P, Ordoñez M, Vaca W, Dhondt A, Suárez J, Toro J (2008) Sedimentary record of terminal Cretaceous accretions in Ecuador: The Yungilla Group in the Cuenca area. J So Am Earth Sci 25:133–144

Janis C (1988) An estimation of tooth volume and hypsodonty índices in ungulate mammals, and the correlation of these factors with dietary preferences. In: Russell DE, Santoro J-P, Sigogneau-Russell D (eds) Proceedings of the 17th International Symposium on Dental Morphology, Paris, 1986. Mém Mus Nat Hist Natl Paris, Ser C, Paris, France:367–387

Jaramillo CA (2002) Response of tropical vegetation to Paleogene warming. Paleobiology 28(2): 222–243

Jaramillo CA, Bayona G, Pardo-Trujillo A, Rueda M, Torres V, Harrington GJ, Mora G (2007) The palynology of the Cerrejón Formation (upper Paleocene) of northern Colombia. Palynology 31:153–189

Jaramillo CA, Dilcher DL (2000) Microfloral diversity patterns of the late Paleocene—Eocene interval in Colombia, northern South America. Geology 28(9):815–818

Jaramillo CA, Rueda MJ, Mora G (2006) Cenozoic plant diversity in the Neotropics. Science 311:1893–1896

Jardine PE, Janis CM, Sarda Sahney S, Benton MJ (2012) Grit not grass: concordant patterns of early origin of hypsodonty in Great Plains ungulates and Glires. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 365–366:1–10.

Kay RF, Madden RH, Vucetich MG, Carlini AA, Mazzoni MM, Ré GH, Heizler M, Sandeman H (1999) Revised geochronology of the Casamayoran South American land mammal age: climatic and biotic implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96 (23):13215–13240

Keating-Bitonti CR, Ivany LC, Affek HP, Douglas P, Samson SD (2011) Warm, not super-hot, temperatures in the early Eocene subtropics. Geology 39(12):771–774

Kielan-Jaworowska Z, Cifelli RL, Luo Z-X (2004) Mammals from the Age of Dinosaurs. Origins, Evolution, and Structure. Columbia University Press, New York

Kielan-Jaworowska Z, Ortiz-Jaureguizar E, Vieytes C, Pascual R, Goin FJ (2007) First ?cimolodontan multituberculate mammal from South America. Acta Palaeontol Pol 52(2):257–262

Koenigswald W von, Goin F, Pascual R (1999) Hypsodonty and enamel microstructure in the Paleocene gondwanatherian mammal Sudamerica ameghinoi. Acta Palaeontol Pol 44(3):163–300

Kramarz AG, Bond M (2008) Revision of Parastrapotherium (Mammalia, Astrapotheria) and other Deseadan astrapotheres of Patagonia. Ameghiniana 45(3):537–551.

Kramarz AG, Bond M (2009) A new Oligocene astrapothere (Mammalia, Meridiunguata) from Patagonia and a new appraisal of astrapothere phylogeny. J Syst Palaeontol 7(1):117–128

Kramarz AG, Bond M, Forasiepi AM (2011) New remains of Astraponotus (Mammalia, Astrapotheria) and considerations on astrapothere cranial evolution. Paläontol Z 85:185–200

Kramarz AG, Vucetich MG, Carlini AA, Ciancio MR, Abello MA, Deschamps CM, Gelfo JN (2010) A new mammal fauna at the top of the Gran Barranca sequence and its biochronological significance. In: Madden RH, Carlini AA, Vucetich MG, Kay RF (eds) The Paleontology of Gran Barranca. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 264–277

Krause JM, Bellosi ES, Raigemborn MS (2010) Lateritized tephric palaeosols from central Patagonia, Argentina: a southern high-latitude archive of Palaeogene global greenhouse conditions. Sedimentology 57:1721–1749

Kunzmann L, Mhor BAR, Bernardez Oliveira MEC (2009) Cearania heterophylla gen. nov. et sp. nov., a fossil gymnosperm with affinities to the Gnetales from the Early Cretaceous of northern Gondwana. Rev Palaeobot Palynology 159:193–212

Legarreta L, Uliana MA (1994) Asociacones de fosiles y hiatos en el Supracretacio-Neogeno de Patagonia: una perspectiva estratigrafoco-sequencial. Ameghiniana 31(3):257–281

Le Roux JP (2012) A review of Tertiary climate changes in southern South America and the Antarctic Peninsula. Part 2. Continental conditions. Sed Geology 247–248:21–38

Le Roux JP, Elgueta S (2000) Sedimentologic development of a Late Oligocene—Miocene forearc embayment, Valdivia Basin Complex, southern Chile. Sed Geology 130:27–44

Line SRP, Bergqvist LP (2005) Enamel structure of Paleocene mammals of the São José de Itaboraí Basin, Brazil, ‘Condylarthra,’ Litopterna, Notoungulata, Xenungulata, and Astrapotheria. J Mammal Evol 25(4):924–928

Little SA, Kembel SW, Wilf P (2010) Paleotemperature proxies from leaf fossils reinterpreted in light of evolutionary history. PLoS One 3(12):e15161, pp. 8

López GM (1995) Suniodon catamarcensis gen et ap. nov. y otros Oldfieldthomasiidae (Notoungulata, Typotheria) del Eoceno de Antofagasta de la Sierra, Catamarca, Argentina. VI Cong Argent Paleontol Bioestrat (Trelew, 1994), Actas:167–172

López GM (2008) Los ungulados de la Formación Divisadero Largo (Eoceno inferior?) de la provincia de Mendoza, Argentina: sistemática y consideraciones bioestratigráficas. Unpublished PhD thesis, Universidad Nacional de la Plata, 415 pp

López GM (2010) Divisaderan: Land Mammal Age or local fauna? In: Madden RH, Carlini AA, Vucetich MG, Kay RF (eds) The Paleontology of Gran Barranca. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 410–417

López G, Bond M (1995) Un nuevo Notopithecinae (Notoungulata, Typotheria) del Terciario inferior de la Puna Argentina. Studia Geol Salamanticensia 31:87–99

López G, Bond M (2003) Una nueva familia de ungulados (Mammalia, Notoungulata) del Paleógeno sudamericano. XIX Jornadas Argentinas de Paleontologia de Vertebrados (Bs.As). Ameghiniana 40(4): suplemento:60

López G, Ribeiro AM, Bond M (2010) The Notohippidae (Mammalia, Notoungulata) from Gran Barranca: preliminary considerations. In: Madden RH, Carlini AA, Vucetich MG, Kay RF (eds) The Paleontology of Gran Barranca. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 143–151

Luterbacher HP, Ali JR, Brinkhuis H, Gradstein FM, Hooker JJ, Monechi S, Ogg JG, Powell J, Röhl, Sanfilippo A, Schmitz B (2004) Paleogene. In: Gradstein F, Ogg J, Smith A (eds) A Geologic Time Scale. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 384–408

Madden RH, Bellosi E, Carlini AA, Heizler M, Vilas JJ, Ré, GH, Kay RF, Vucetich MG (2005) Geochronology of the Sarmiento Formation at Gran Barranca and elsewhere in Patagonia: calibrating middle Cenozoic mammal evolution in South America. Actas del XVI Congreso Geológico Argententina, La Plata, Tomo IV:411–412

Malumián N (1999) La sedimentación en la Patagonia Extraandina. Geologia Argentina. Inst Geol Recursos Mineral Anal 29(19):557–612

Malumián N, Náñez C (2011) The Late Cretaceous-Cenozoic transgressions in Patagonia and the Fuegian Andes: foraminifera, palaeoecology, and palaeogeography. Biol J Linn Soc 103:269–288

Mann P, Escalona A, Castillo M (2006) Regional geologic and tectonic setting of the Maracaibo supergiant basin, western Venezuela. AAPG Bull 90:445–477

Marenssi SA (2006) Eustatically controlled sedimentation recorded by Eocene strata of the James Ross Basin, Antarctica. In: Francis JE, Pirrie D, Crame JA (eds) Cretaceous-Tertiary High-Latitude Paleoenvironments, James Ross Basin, Antarctica. Geol Soc London Spec Publ 258:125–133

Marquillas RA, del Papa C, Sabino IF (2005) Sedimentary aspects and paleoenvironmental evolution of a rift basin: Salta Group (Cretaceous-Paleocene), northwestern Argentina. Internatl J Earth Sci (Geol Rundsch) 94:94–113

Marshall LG (1978) Evolution of the Borhyaenidae, extinct South American predaceous marsupials. Univ Calif Publ Geol Sci 117:1–89

Marshall LG, Butler RF, Drake RE, Curtis DH (1981) Calibration of the beginning of the Age of Mammals in Patagonia. Science 212:43–45

Marshall LG, Hoffstetter R, Pascual R (1983) Mammals and stratigraphy: geochronology of the continental mammal-bearing Tertiary of South America. Palaeovertebrata Mem Extraord:1–93

Marshall LG, Sempere T, Butler RF (1997) Chronostratigraphy of the mammal-bearing Paleocene of South America. J So Am Earth Sci 10(1):49–70

Massabie AE (1995) Estratigrafía del límite Cretácico-Terciario de la región del Río Colorado, según el perfil de Casa de Piedra, provincia de La Pampa. 12° Cong Geol Argent 2° Cong Exploración de Hidrocarburos (Mendoza, 1993), Actas 2:124–131

Mazzoni MM (1985) La Formación Sarmiento y el vulcanimo paleógeno. Rev Asoc Geol Argent 40:60–68

McInerney FA, Wing SL (2011) The Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum: a perturbation of carbon cycle, climate, and biosphere with implications for the future. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 39:489–516

McKenna MC, Bell SJ (2002) Mammal Classification. ftp://amnh.org/people/mckenna/Mammalia.txn.sit. Read, displayed and searchable with Unitaxon© Browser. CD-ROM. 2002. Boulder, Colorado: Mathemaethetics, Inc.

McKenna MC, Wyss AR, Flynn JJ (2006) Paleogene pseudoglyptodont xenarthrans from central Chile and Argentine Patagonia. Am Mus Novitates 3536:1–18

McQuarrie N, Horton BK, Zandt G, Beck S, DeCelles PG (2005) Lithospheric evolution of the Andean fold-thrust belt, Bolivia, and the origin of the central Andean plateau. Tectonophys 399:15–37

Medeiros RA, Bergqvist LP (1999) Paleocene of the São José de Itaboraí Basin, Río de Janeiro, Brazil: lithostratigraphy and biostratigraphy. Acta Geol Leopold XXII (48):3–22

Melchor RN, Genise JF, Miquel SE (2002) Ichnology, sedimentology and paleontology of Eocene calcareous paleosols from a palustrine sequence, Argentina. Palaios 17:16–35

Melendi DL, Scafati LH, Volkheimer W (2003) Palynostratigraphy of the Paleogene Huitrera Formation in N-W Patagonia, Argentina. N Jb Geol Paläontol Abh 28(2):205–273

Menéndez CA, Caccavari MA (1975) Las especies de Nothofagidites (polen fósil de Nothofagus) de sedimentos Terciarios y Cretácicos de Estancia La Sara, Norte de Tierra del Fuego, Argentina. Ameghiniana 12:165–183

Michalak I, Zhang L-B, Renner SS (2010) Trans-Atlantic, trans-Pacific and trans-Indian Ocean dispersal in the small Gondwanan Laurales family Hernandiaceae. J Biogeogr 37:1214–1226

Miller KG, Fairbanks RG, Mountain GS (1987) Tertiary oxygen isotope synthesis, sea level history, and continental margin erosion. Paleocean 2:1–19

Mohr B, Bernardes de Oliveira EMC, Barale G, Ouaja M (2006) Palaeogeographic distribution and ecology of Klitzschophyllites, an early Cretaceous angiosperm in southern Laurasia and northern Gondwana. Cretaceous Res 27:464–472

Mones A (1982) An equivocal nomenclature: what means hypsodonty? Paläontol Zeit 56:107–111

Moreira-Muñoz A (2007) The Austral floristic realm revisited. J Biogeogr 34:1649–1660

Morley RJ (2000) Origin and Evolution of Tropical Rain Forests. Wiley, New York

Morrone JJ (2002) Biogeographical regions under track and cladistic scrutiny. J Biogeogr 29:149–152

Morrone JJ (2006) Biogeographic areas and transition zones of Latin America and the Caribbean islands based on panbiogeographic and cladistic analyses of the entomofauna. Annu Rev Entomol 51:467–94

Mpodozis C, Arriagada C, Basso M, Roperch P, Cobbold P, Reich M (2005) Late Mesozoic to Paleogene stratigraphy of the Salar de Atacama Basin, Antofagasta, northern Chile: implications for tectonic evolution of the Central Andes. Tectonophys 399:125–154

Muizon C de (1991) La fauna de mamiferos de Tiupampa (Paleoceno inferior, Formación Santa Lucia), Bolivia. In: Suarez-Soruco R (ed) Facies y Fosiles de Bolivia, vol. 1 (Vertebrados), Bolivia. Rev Technica YPFB, pp 575–624

Muizon C de (1998) Mayulestes ferox, a borhyaenoid (Metatheria, Mammalia) from the early Paleocene of Bolivia. Phylogenetic and paleobiologic implications. Geodiversitas 20 (1): 19–142

Muizon C de, Brito IM (1993) Le bassin calcaire de Sáo José de Itaboraí (Rio de Janeiro, Brésil): ses relacions fauniques avec le site de Tiupampa (Cochambamba, Bolivie). Annal Palaeontol 79: 233–269

Muizon C de, Cifelli RL (2000) The ‘condylarths’ (archaic Ungulata, Mammalia) from the early Palaeocene Tiupampa (Bolivia): implications on the origin of the South American ungulates. Geodiversitas 22(1):47–150

Murphy BH, Farley KA, Zachos JC (2010) An extraterrestrial 3He-based timescale for the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) from Walvis Ridge, IODP site 1266. Geochem Cosmochem Acta 74:5098–5108

Musser AM (2006) Furry egg-layers: monotreme relationships and radiations. In: Merrick JR, Archer M, Hickey GM, Lee MSY (eds) Evolution and Biogeography of Australasian Vertebrates. Australian Scientific Publishing, Sydney, pp 523–550

Nilsson MA, Churakov G, Sommer M, Tran NV, Zemann A, Brosius J, Schmitz J (2010) Tracking marsupial evolution using archaic genomic retroposon insertions. PloS Biology 8(7):1–9

Nullo F, Combina A (2011) Patagonian continental deposits (Cretaceous - Tertiary). Biol J Linn Soc 103(2):289–304

Oliveira EV, Goin FJ (2011) A reassessment of bunodont metatherians from the Paleogene of Itaboraí (Brazil): systematics and age of the Itaboraian SALMA. Rev Bras Paleontol 14(2):105–136

Ortiz-Jaureguizar E, Cladera GA (2006) Paleoenvironmental evolution of southern South America during the Cenozoic. J Arid Environ 66:498–532

Ortiz-Jaureguizar E, Pascual R (1989) South American land-mammal faunas during the Cretaceous-Tertiary transition: evolutionary biogeography. Contrib simposios sobre el Cretac Amér Latina, Parte A: Eventos y registro sedimentario:A231–A251

Otero A, Torres T, Le Roux JP, Hervé F, Fanning CM, Yury-Yáñez RE, Rubilar-Rogers D (2012) Late Eocene age proposal for the Loreto Formation (Brunswick Peninsula, southernmost Chile), based on fossil cartilaginous fishes, paleobotany and radiometric evidence. Andean Geol 39:180–200

Ottone EG (2007) A new palm trunk from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentina. Ameghiniana 44(4):719–725

Padula E, Minggram A (1968) Estratigrafia, distribución, y cuadro geotectónico-sedimentario del “Triasico” en el subsuelo de la llanura Chaco-Paranense. Terces Jornad Geol Argent, Buenos Aires 1:191–231

Palazzesi L, Barreda V (2007) Major vegetation trends in the Tertiary of Patagonia (Argentina): a qualitative paleoclimatic approach based on palynological evidence. Flora 202:328–337

Pälike H, Norris RD, Herrle JO, Wilson PA, Cozall HK, Lear CH, Shackleton NJ, Tripati AL, Wade BS (2006) The heartbeat of the Oligocene climate system. Science 314:1894–1898

Palma-Heldt S, Alfaro G (1982) Antecedentes palinológicos preliminaries para la correlaciónde los mantos de carbon del terciario de la Provincia de Valdivia. Segundo Cong Geol Chileño, Concepción, Chile. Abs, v1:A207-A208

Panti C (2010) Diversidad Flóistica durante el Paleógeno en Patagonia austral. Unpublished PhD thesis, Universidad Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, 201 pp

Panti C, Césari SN, Marenssi SA, Olivero EO (2007) A new araucarian fossil species from the Paleogene of southern Argentina. Ameghiniana 44:215–222

Pardo-Casas F, Molnar P (1987) Relative motion of the Nazca (Farallon) and South American plates since Late Cretaceous time. Tectonics 6(3):233–248

Parra M, Mora A, Jaramillo C, Torres V, Zeilinger G, Strecker MR (2010) Tectonic controls on Cenozoic foreland basin development in the north-eastern Andes, Colombia. Basin Res 22:874–903

Parras AM, Casadio S, Pires M (1998) Secuencias depositacionales del Grupo Malargüe y el límite Cretácio-Paleógeno, en el sur de la Provincia de Mendoza, Argentina. Asoc Palaeontol Argent Pub Espec 5:61–69

Pascual R (1980a) Nuevos y singulars tipos ecológicos de marsupiales extinguidos de América del Sur (Paleocene tardío o Eoceno temprano) del noroeste argentino. II Cong Argent Paleont y Bioestrat Buenos Aires, Actas 2:151–173

Pascual R (1980b) Prepidolopidae, nueva familia de Marsupialia Didelphoidea del Eocene sudamericano. Ameghiniana 17:216–242

Pascual R (1983) Novedosos marsupiales paleógenos de la Formación Pozuelos (Grupo Pastos Grandes) de al Puna, Salta, Argentina. Ameghiniana 20(3–4):265–280

Pascual R (1996) Late Cretaceous-Recent land-mammals. An approach to South American geobiotic evolution. Mastozoología Neotropical 3:133–152

Pascual R (2006) Evolution and geography: the biogeographic history of South American land mammals. Ann Missouri Bot Garden 93:209–230

Pascual R, Archer M, Ortiz-Jaureguizar E, Prado JL, Godthelp H, Hand SJ (1992) First discovery of monotremes in South America. Nature 356:704–705

Pascual R, Bond M, Vucetich MG (1981) El Subgrupo Santa Barbara (Grupo Salta) y sus vertebrados. Cronologia paleoambientes y paleobiogeografia. VIII Cong Geol Argent Actas (3):743–758

Pascual R, Goin FJ, Carlini AA (1994) New data on the Groeberiidae: unique late Eocene-early Oligocene South American marsupials. J Vertebr Paleontol 14 (2):247–259

Pascual R, Goin FJ, González P, Ardolino A, Puerta PF (2000) A highly derived docodont from the Patagonian Late Cretaceous: evolutionary implications for Gondwanan mammals. Geodiversitas 22(3):395–414

Pascual R, Ortega Hinojosa EJ, Gondar D, Tonni E (1965) Las edades del Cenozóico mamalifero de la Argentina, con especial atención a aquellas del territorio bonaerense. Anal Comin Investig Cient Buenos Aires 6:165–193

Pascual R, Ortiz-Jaureguizar E (1990) Evolving climates and mammal faunas in Cenozoic South America. J Human Evol 19:23–60

Pascual R, Ortiz-Jaureguizar E (1991) El ciclo faunístico cochabambiano (Paleoceno temprano): su incidencia en la historia biogeográfica de los mamíferos sudamericanos. In: Suárez-Soruco R (ed), Fósiles y Facies de Bolivia, Rev Técnica. YPFB 12(3)–4):559–574

Pascual R, Ortiz-Jaureguizar E (1992) Evolutionary pattern of land mammal faunas during the Late Cretaceous and Paleocene in South America: a comparison with the North American pattern. Ann Zool Fennici 28:245–252

Pascual R, Ortiz-Jaureguizar E (2007) The Gondwanan and South American episodes: Two Major and Unrelated Moments in the History of the South American Mammals. J Mammal Evol 14:75–137

Pascual R, Ortiz-Jaureguizar E, Prado JL (1996) Land mammals: Paradigm for Cenozoic South American geobiotic evolution. Münchner Geowissen Abhand (A) 30:265–319

Patterson B, Pascual R (1972) The fossil mammal fauna of South America. In: Keast A, Erk FC, Glass B (eds) Evolution, Mammals, and Southern Continents. State University of New York Press, Albany, pp 247–309

Paula-Couto C (1952) Fossil mammals from the beginning of the Cenozoic in Brazil. Condylarthra, Litopterna, Xenungulata and Astrapotheria. Bull Am Mus Nat Hist 99(6):359–394

Peppe D, Royer AL, Cariglino B, Oliver SY, Newman S, Leight E, Enikolopov G, Fernandez-Burgos M, Herrera F, Adams JM, Correa E, Currano ED, Erickson JM, Hinojosa LF, Hoganson JW, Iglesias A, Jaramillo CA, Johnson KR, Jordan GJ, Kraft NJB, Lovelock EC, Lusk CH, Ninemets U, Peñuelas J, Rapson G, Wing SL, Wright IJ (2011) Sensitivity of leaf size and shape to climate: global patterns and paleoclimatic applications. New Phytol 190:724–739

Petriella B (1972) Estudio de las maderas petrificadas del Tericario Inferior del area central de Chubut (Cerro Bororó). Rev Museo La Plata, Sección Paleontol 6(41):159–254

Petriella B, Archangelsky S (1975) Vegetación y Ambiente en el Paleoceno de Chubut. Primer Cong Argent Paleontol Bioestrat Tucumán, Actas 1:257–270

Pinto L, Hérail G, Charrier R (2004) Sedimentación sintectónica asociada a las estructuras neógenas en la Precordillera de la zona de Moquella Tarapacá (19°15’S, norte de Chile). Rev Geol Chile 31:19–44

Prámparo MG (2005) Palynological study of the Lower Cretaceous San Luis Basin. In: IANIGLA (ed) IANIGLA 30 años:221–225

Prámparo MG, Quattriocchio M, Gandolfo MA, Zamaloa M del C, Romero E (2007) Historia evolutiva de las angiospermas (Cretácico-Paleógeno) en Argentina a través de los registros paleoflorísticos. Asoc Paleontol Espec11, Ameghiniana 50th Aniversario:157–172

Prasad V, Strömberg CAE, Alimohammadian H, Sahni A (2005) Dinosaur coprolites and the early evolution of grasses and grazers. Science 310:1177–1180

Prentice ML, Matthews RK (1988) Cenozoic ice-volume history: development of a composite oxygen isotope record. Geology 16:963–966

Prevosti F, Forasiepi A, Zimicz N (2011) The evolution of the Cenozoic terrestrial mammalian predator guild in South America: competition or replacement? J Mammal Evol, doi 10.1007/s10914-011-9175-9

Pross J, Contreras L, Bijl PK, Greenwood DR, Bohaty SM, Schouten S, Bendle, JA, Röhl, U, Tauxe L, Raine I, Huck CE, van de Flierdt T, Jamieson SSR, Stickley CE, van de Schootbrugge B, Escutia C, Brinkhuis H, & Integrated Ocean Drilling Program Expedition 318 Scientists (2012) Persistent near-tropical warmth on the Antarctic continent during the early Eocene epoch. Nature 488:73–77

Puebla G (2010) Evolución de las comunidades vegetales basada en el studio de la flora fósil presente en la Formación La Cantera, Cretácico temprano, Cuenca de San Luis. Unpublished PhD thesis. Universidad Nacional de San Luis, San Luis, 166 pp

Pujana RR (2009) Fossil woods from the Oligocene of southwestern Patagonia (Río Leona Formation). Atherospermataceae, Myrtaceae, Leguminosae and Anacardiaceae. Ameghiniana 46:523–535

Pujos F, de Iuliis G (2007) Late Oligocene Megatherioidea fauna (Mammalia, Xenarthra) from Salla-Luribay (Bolivia): new data on basal sloth radiation and Cingulata-Tardigrada split. J Vertebr Paleontol 27(1):132–144

Quattrocchio MF, Volkheimer W, Borromei AM, Martinez MA (2011) Changes of the palynobiotas in the Mesozoic and Cenozoic: a review. Biol J Linn Soc 103(2):380–396

Quattrocchio MF, Volkheimer W, del Papa C (1997) Palynology and paleoenvironment of the “Faja Gris” Mealla Formation (Salta Group) at Garabatal Creek (NW Argentina). Palynology 21:231–247

Raigemborn M, Brea M, Zucol A, Matheos S (2009) Early Paleogene climate at mid latitude in South America: mineralogical and paleobotanical proxies from continental sequences in Golfo San Jorge basin (Patagonia, Argentina). Geol Acta 7(1–2):125–148

Raigemborn MS, Krause JM, Bellosi E, Matheos SD (2010) Redefinición estratigráfica del Grupo Río Chico (Paleógeno inferior), en el norte de La Cuenca del Golfo San Jorge, Chubut. Rev Asoc Geol Argent 62(2):239–256

Ré GH, Bellosi ES, Heizler M, Vilas JF, Madden RH, Carlini AA, Kay RF, Vucetich MG (2010a) A geochronology for the Sarmiento Formation at Gran Barranca. In: Madden RH, CarliniAA, Vucetich MG, Kay RF (eds) The Paleontology of Gran Barranca. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 46–58

Ré GH, Geuna SE, Vilas JF (2010b) Paleomagnetism and magnetostratigraphy of Sarmiento Formation (Eocene - Miocene) at Gran Barranca, Chubut, Argentina. In: Madden RH, Carlini AA, Vucetich MG, Kay RF (eds) The Paleontology of Gran Barranca. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 32–45

Ré GH, Madden R, Heizler M, Vilas JF, Rodriguez ME (2005) Polaridad magnénetica de las sedimentitas de la Formación Sarmiento (Gran Barranca de Lago Colhue Huapi, Chubut, Argentina). Actas del XVI Congreso Geológico Argentino, La Plata, Tomo IV:387–394

Reguero MA, Candela AM, Cassini GH (2010) Hypsodonty and body size in rodent-like notoungulates. In: Madden RH, Carlini AA, Vucetich MG, Kay RF (eds) The Paleontology of Gran Barranca. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 362–371

Reguero MA, Croft DC, López GM, Alonso RN (2008) Eocene archaeohyracids (Mammalia: Notoungulata: Hegetotheria) from the Puna, northwest Argentina. J So Am Earth Sci 26: 225–233

Reguero MA, Prevosti FJ (2010) Rodent-like notoungulates (Typotheria) from Gran Barranca, Chubut Province, Argentina: phylogeny and systematics In: Madden RH, Carlini AA, Vucetich MG, Kay RF (eds) The Paleontology of Gran Barranca. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 153–169

Renner SS, Strijk JS, Strasberg D, Thébaud C (2010) Biogeography of the Monimiaceae (Laurales): a role for East Gondwana and long-distance dispersal, but not West Gondwana. J Biogeogr 37:1227–1238

Ribeiro AM, López GM, Bond M (2010) The Leontiniidae (Mammalia, Notoungulata) from the Sarmiento Formation at Gran Barranca, Chubut Province, Argentina. In: Madden RH, Carlini AA, Vucetich MG, Kay RF (eds) The Paleontology of Gran Barranca. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 170–181

Riccardi AC (1988) The Cretaceous System of southern South America. Geol Soc Am Mem 168, 161 pp

Rich TH, Rich PV, Flannery TF, Kear BP, Cantrill D, Komarower P, Kool L, Pickering D, Trusler P, Morton S, van Klaveren N, Fitgzgerald MG (2009) An Australian multituberculate and its paleobiogeographic implications. Acta Palaeontol Pol 54(1):1–6

Rich TH, Vickers-Rich P, Trusler P, Flannery TF, Cifeli R,Constantine A, Kool L, van Klaveren N (2001) Monotreme nature of the Australian Early Cretaceous mammal Teinolophos. Acta Palaeontol Pol 46(1):113–118

Romero E (1986) Paleogene phytogeography and climatology of South America. Ann Missouri Bot Garden 73:449–461

Romero E (1993) South American paleofloras. In: Goldblatt P (ed) Biological Relationships between Africa and South America. Yale University Press, New Haven/London, pp 62–85

Romero EJ, Hickey LJ (1976) Fossil leaf of Akaniaceae from Paleocene beds in Argentina. Bull Torrey Bot Club103:126–131

Roth S (1903) Noticias preliminares sobre nuevos mamíferos fósiles del Cretáceo superior y Terciario inferior de la Patagonia. Rev Mus La Plata 11:133–158

Rouchy JM, Camoin G, Casanova J, Deconinck JF (1993) The central palaeo-Andean basin of Bolovia (Potosí área) during the Late Cretaceous and early Tertiary: reconstruction of ancient saline lakes using sedimentological, paleoecological and stable isotope records. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 105:179–198

Rougier GW, Chornogubsky L, Casadio S, Arango NP, Gaillombardo A (2009a) Mammals from the Allen Formation, Late Cretaceous, Argentina. Cretaceous Res 30:223–238

Rougier GW, Forasiepi AM, Hill RV, Novacek MJ (2009b) New mammalian remains from the Late Cretaceous La Colonia Formation, Patagonia, Argentina. Acta Palaeontol Pol 54 (2):195–212

Rougier GW, Martinelli AG, Forasiepi AM, Novacek MJ (2007) New Jurassic mammals from Patagonia, Argentina: a reappraisal of Australosphenidan morphology and interrelationships. Am Mus Novitates 3566:1–54

Rougier GW, Wible JR, Beck RMD, Apesteguía S (2012) The Miocene mammal Necrolestes demonstrates the survival of a Mesozoic nontherian lineage into the late Cenozoic of South America. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109(49):20053–20058

Rowe TF, Rich T, Vickers-Rich P, Springer MS, Woodburne MO (2008) The oldest platypus and its bearing on divergence timing of the platypus and echidna clades. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105(4):1238–1242

Ruiz LE (2006) Estudio sedimetológico y estratigráfico de las formaciones Paso del Sapo y Lefipán en el valle medio del Río Chubut. Trabajo final de licenciatura, Univ. de Buenos Aires, Dept. Geología, 76

Salas R, Sánchez J, Chacaltana C (2006) A new pre-Deseadan pyrothere (Mammalia) from northern Peru and the wear facets of molariform teeth of Pyrotheria. J Vertebr Paleontol 26:760–769

Scafati L, Mellendi DL, Volkheimer W (2009) A Danian subtropical lacustrine palynobiota from South America (Bororó Formation, San Jorge Basin, Patagonia - Argentina. Geol Acta 7(1–2):35–61

Scarano AC, Carlini AA, Illius AW (2011) Interatheriidae (Typotheria; Notoungulata), body size and paleoecology. Mammal Biol 76:109–114

Scasso RA, Aberhan M, Ruiz L, Weidemeyer S, Medina FA, Kiesling W (2012) Integrated bio- and lithofacies analysis of coarse-grained, tide-dominated deltaic environments across the Cretaceous/Paleocene boundary in Patagonia, Argentina. Cretaceous Res 36:37–57

Scillato-Yané GJ (1977) Sur quelques Glyptodontidae nouveaux (Mammalia, Edentata) du Déséadien (Oligocene inferieur) de Patagonie (Argentine). Bull Mus Nat Hist Natl Paris, Sci de la Terre (64):249–262

Scillato-Yane GJ, Pascual R (1964) Un peculiar Paratheria, Edentata (Mammalia) del Paleoceno de Patagonia. Primeras Jor Argent Paleont Vertebr, Resumen Comm Sci Investig La Plata, Argent:15

Sempere T, Butler RF, Richard DR, Marshall LG, Sharp W, Swisher CC III (1997) Stratigraphy and chronology of Upper Cretaceous–lower Paleocene strata in Bolivia and northwest Argentina. Geol Soc Am Bull 109(6):709–727

Shockey BJ, Anaya F (2008) Postcranial osteology of mammals from Salla, Bolivia (late Oligocene): form, function, and phylogenetic implications. In: Sargis EJ, Dagosto M (eds) Mammalian Evolutionary Morphology: A Tribute to Frederick S. Szalay. Springer Science and Business Media, B.V, New York, pp 135–157

Shockey BJ, Anaya F (2011) Grazing in a new late Oligocene mylodontid sloth and a mylodontid radiation as a component of the Eocene-Oligocene faunal turnover and the early spread of grassland/savannas in South America. J Mammal Evol 18:101–115

Sigé B, Sempere T, Butler RF, Marshall LG, Crochet J-Y (2004) Age and stratigraphic reassessment of the fossil-bearing Laguna Umayo red mudstone unit, SE Peru, from regional stratigraphy, fossil record, and paleomagnetism. Geobios 37:771–793

Sigogneau-Russell D (1991) First evidence of Multituberculata (Mammalia) in the Mesozoic of Africa. N Jb Paläontol Monats 2:119–125

Simpson GG (1933) Stratigraphic nomenclature of the early Tertiary of central Patagonia. Am Mus Novitates 644:1–13

Simpson GG (1935) Occurrence and relationships of the Río Chico fauna of Patagonia. Am Mus Novitates 818:1–21

Simpson GG (1941) The Eocene of Patagonia. Am Mus Novitates 1120:1–15

Simpson GG (1971) The evolution of marsupials in South America. An Acad Brasi Ciênc 43:103–119

Soria MF (1989) Notopterna: un nuevo Orden de mamìferos ungulados eógenos de América del Sur. Parte II: Notonychops powelli gen et sp. nov (Notonychopidae nov.) de la Formación Río Loro (Paleoceno medio), provincia de Tucumán, Argentina. Ameghiniana 25:259–272

Soria MF, Bond M (1984) Adiciones al conicimiento de Trigonostylops Ameghino, 1897 (Mammalia, Astrapotheria, Trigonostylopidae). Ameghiniana 21(1):43–51

Soria MF, Powell JE (1982) Un primitive Astrapotheria (Mammalia) y edad de la Foramación Río Loro, Provincia de Tucumán, República Argentina. Ameghiniana 18(2–4):155–168

Spalletti LA, Matheos SD, Merodio JC (1999) Sedimentitas carbonaticas Cretacico-Terciaris de la platforma norpatagonica. XII Cong Geol Argent II Cong Explor Hidrocarburos Actas 1:249–257

Spalletti L, Mazzoni M (1977) Sedimentologia del Grupo Sarmiento en un perfil ubicado al sudeste del lago Colhue-Huapi, provincia de Chubut. Obra Centenario Museo de La Plata 4:261–283

Spalletti L, Mazzoni M (1979) Estratigrafia de la Formación Sarmiento en la barranca sur del Lago Colhue-Huapi, provincia del Chubut. Rev Asoc Argent 34:271–281

Spicer RA, Yang J (2010) Quantification of uncertainties in fossil leaf paleoaltimetry: does leaf size matter? Tectonics 29, TC6001, doi:10.1029/2010TC002741, 13 pp

Spikings RA, Crowhurst PV, Winkler W, Villagomez D (2010) Syn- and post-accretionary cooling history of the Ecuadorian Andes constrained by their in-situ and detrital thermochronologic record. J So Am Earth Sci 30:121–133

Stevens PF (2007) Angiosperm Phylogeny Website, Version 8, June 2007. http://www.mobot.org/MOBOT/research/APweb/

Stirton RA (1947) Observations on evolutionary rates in hypsodonty. Evolution 1(1–2):32–41

Suárez M. de la Cruz R, Troncoso A (2000) Tropical/subtropical upper Paleocene - lower Eocene fluvial deposits in eastern central Patagonia, Chile (46°45'S). J So Am Earth Sci 13:527–536

Sucerquia P, Jaramillo C (2007) Early Cretaceous floras from central Colombia. Abs Proc Fortieth Annl Mtg Amer Assoc Strat Paleontol:64

Tejedor MF, Goin FJ, Chornogubsky L, López GM, Gelfo JN, Bond M, Woodburne MO, Gurovich Y, Reguero M (2011) Persistence of a Mesozoic, non-therian mammalian lineage in the mid-Paleogene of Patagonia. IV Cong Latinoamericano paleontol Vertebrad San Juan, Abs:244

Tejedor MF, Goin FJ, Gelfo JN, López G, Bond M, Carlini AA, Scillato-Yané GJ, Woodburne MO, Chornogubsky L, Aragón E, Reguero MA, Czaplewski NJ, Vincon S, Martin GM, Ciancio MR (2009) New early Eocene mammalian fauna from western Patagonia, Argentina. Am Mus Novitates 3638:1–43

Terada K, Asakawa TO, Nishida H (2006) Fossil woods from the Loretto Formation of Las Minas, Magallanes (XII) Region, Chile. In: Nishida H (ed) Post-Cretaceous Floristic Changes in Southern Patagonia, Chile. Chuo University, Tokyo, pp 91–101

Thiry M, Aubry M-P, Dupuis C, Sinha A, Stott LD, Berggren WA (2006) The Sparnacian deposits of the Paris Basin: δ13C isotope stratigraphy. Stratigraphy 3(2):119–138

Tófalo OR, Morrás HJM (2009) Evidencias paleoclimáticas en duricostras, paleoselos y sedimentitas silicoclásticas del Cenozoico de Uruguay. Rev Asoc Geol Argent 65:674–686

Tsukui K, Clyde WC (2012) Fine-tuning the calibration of the early to middle Eocene geomagnetic polarity time scale: Paleomagnetism of radioisotopically dated tuffs from Laramide foreland basins. Geol Soc Am Bull 124 (5/6):870–885

Troncoso A (1992) La flora Terciaria de quinaimavida (VII Región, Chile). Bol Mus Nac Hist Natl Chile 43:155–178

Troncoso A, Romero EJ (1998) Evolución de las comunidades florísticas en el extremo sur de sudamérica durante el cenofítico. In: Fortunato R, Bacigalupo N (eds) Proc VI Cong Latinoamericano Bot Mon Syst Bot Missouri Bot Garden, pp 149–172

Troncoso A, Suárez M, de la Cruz R, Palma Held S (2002) Paleoflora de la formación Ligorio Márquez (XI Región, Chile) en su localidad tipo: sistemática, edad e implicancias paleclimáticas. Rev Geol Chile 29:113–135

Vajda-Santiváñez V (1999) Miospores from Upper Cretaceous-Paleocene strata in northwestern Bolivia. Palynology 23:181–196

Vajda-Santiváñez V, McLoughlin S (2005) A new Maastrichtian - Paleocene Azolla species from Bolivia, with a comparison of the global record of coeval Azolla microfossils. Alcheringa 29:305–329

Vallejo C, Winkler W, Spikings RA, Luzieux L, Heller F, Bussy F (2009) Mode and timing of terrane accretion in the forearc of the Andes in Ecuador. In: Kay SM, Ramos VA, Dickinson WR (eds) Backbone of the Americas: Shallow Subduction, Plateau Uplift, and Ridge and Terrane Collision. Geol Soc Am Mem 204: 197–216

Varela AN (2011) Sedimentologia y modelos deposicionales de la Formatión Mata Amarilla, Cretácico de la Cuenca Austral, Argentina. Unpublished PhD thesis, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata, 290 pp

Varela AN, Poiré DG, Martin T, Gerdes A, Goin FJ, Gelfo JN, Hoffman S (2012) U-Pb zircon constraints on the age of the Cretaceous Mata Amarilla Formation, southern Patagonia, Argentina: its relationship with the evolution of the Austral Basin. Andean Geol 00:00–00.

Villagrán C, Hinojosa LF (1997) Historia de los bosques del sur de Sudamérica, I: antecedentes paleobotánicos, geológicos y climáticos del cono sur de América. Rev Chil Hist Natl 70:225–239

Villarroel CA (1987) Características y afinidades de Etayoa n. gen., tipo de una nueva familia de Xenungulata (Mammalia) del Paleocene medio (?) de Colombia. Comun Paleontol Mus Hist Natl Montevideo 19(1):241–253

Viramonte JG, Kay SM, Becchio R, Escayola M, Novitski I (1999) Cretaceous rift related magmatism in central-western South America. J So Am Earth Sci 12:109–121

Vizcaíno SF, Cassini GH, Toledo N, Bargo MS (2012) On the evolution of large size in mammalian herbivores of Cenozoic faunas of southern South America. In: Patterson BD, Costa LP (eds) Bones, Clones, and Biomes. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 76–101

Vucetich MG, Vieytes EC, Pérez ME, Carlini AA (2010) The rodents from La Cantera and the early evolution of caviomorphs in South America. In: Madden RH, Carlini AA, Vucetich MG, Kay RF (eds) The Paleontology of Gran Barranca. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 193–205

Westerhold T, Röhl U, Donner B, McCarren H, Zachos J (2009) Latest on the absolute age of the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM): new insights from exact stratgraphic position of key ash layers +19 and -17. Earth Planet Sci Let 287: 412–419

Westerhold T, Röhl U, Donner B, McCarren H, Zachos J (2011) A complete high resolution Paleocene benthic stable isotope record for the Central Pacific (ODP site 1209). Paleocean. doi:10.1029/2010PA002092

Wilf P (2000) Late Paleocene—early Eocene climate changes in southwestern Wyoming: paleobotanical analysis. Geol Soc Am Bull 112:292–307

Wilf P, Cúneo NR, Johnson KR, Hicks JF, Wing SL, Obradovich JD (2003) High plant diversity in Eocene South America: evidence from Patagonia. Science 300:122–125

Wilf P, Johnson KR, Cúneo NR, Smith ME, Singer BS, Gandolfo MA (2005) Fossil plant diversity at Laguna del Hunco and Río Pichileufú, Argentina. Am Nat 165(6):634–650

Wilf P, Little SA, Iglesias A, Zamaloa MC, Gandolfo MA, Cúneo NR, Johnson KR (2009) Papuacedrus (Cupressaceae) in Eocene Patagonia: a new fossil link to Australasia rainforests. Am J Bot 96:2031–2047

Wilf P, Singer BS, Zamaloa, M. del Carmen, Johnson KR, Cúneo NR (2010) Early Eocene 40Ar/39Ar age for the Pampa de Jones plant, frog, and insect biota (Huitrera Formation, Neuquén Province, Patagonia, Argentina). Ameghiniana 47(2):207–216

Wilf P, Wing SL, Greenwood DR, Greenwood CL (1998) Using fossil leaves as paleoprecipitation indicators: an Eocene example. Geology 26:203–206

Wing SL (1998) Late Paleocene—early Eocene floral and climatic change in the Bighorn Basin, Wyoming. In: Aubry M-P, Lucas S, Berggren WA (eds) Late Paleocene – Early Eocene Biotic and Climatic Events. Columbia University Press, New York, pp 371–391

Wing SL, Alroy J, Hickey LJ (1995) Plant and mammal diversity in the Paleocene to early Eocene of the Bighorn Basin. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 115:117–155

Wing SL, Harrington GJ (2001) Floral response to rapid warming in the earliest Eocene and implications for concurrent faunal change. Paleobiology 27(3):539–563

Wing SL, Herrera F, Jaramillo CA, Gómez-Navarro C, Wilf P, Labandeira CC (2010) Late Paleocene fossils from the Cerrejón Formation, Colombia, are the earliest record of Neotropical rainforest. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106(44):18627–18632

Wolfe JA (1978) A paleobotanical interpretation of Tertiary climates in the Northern Hemisphere. Am Scient 66:694–703

Wolfe JA, Poore RZ (1982) Tertiary marine and nonmarine climatic trends. In: National Research Council (eds) Effects of Past Global Change on Life. National Academy Press, Washington, DC, pp 154–158

Wood AE, Patterson B (1959) The rodents of the Deseadan Oligocene of Patagonia and the beginnings of South American rodent evolution. Bull Mus Comp Zool 120:279–428

Woodburne MO (1996) Precision and resolution in mammalian chronostratigraphy; principles, practices, examples. J Vertebr Paleontol 16(3):531–555

Woodburne MO (2004a) Definition. In: Woodburne MO (ed) Late Cretaceous and Cenozoic Mammals of North America: Biostratigraphy and Geochronology. Columbia University Press, New York, pp xxi–xv

Woodburne MO (2004b) Late Cretaceous and Cenozoic Mammals of North America: Biostratigraphy and Geochronology. Columbia University Press, New York

Woodburne MO, Case JA (1996) Dispersal, vicariance, and the Late Cretaceous to early Tertiary land mammal biogeography from South America to Australia. J Mammal Evol 3(2):121–161

Woodburne MO, Gunnell GF, Stucky RK (2009a) Climate directly influences Eocene mammal faunal dynamics in North America. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106(32):13399–13403

Woodburne MO, Gunnell GF, Stucky RK (2009b) Land Mammal Faunas of North America Rise and Fall during the Early Eocene Climatic Optimum. Denver Mus Nature Sci Ann 1:1–75

Wyss AR, Flynn JJ, Norell MA, Swisher CC III, Charrier R, Novacek MJ, McKenna MC (1993) South America’s earliest rodent and recognition of a new interval of mammalian evolution. Nature 365:434–437

Wyss AR, Norell MA, Flynn JJ, Novacek MJ, Charrier R, McKenna MC, Swisher CC III, Frassinetti D, Salinas P, Meng J (1990) A new early Tertiary mammal fauna from central Chile: implications for Andean stratigraphy and tectonics. J Vertebr Paleont 10(4):518–522

Yabe A, Uemura K, Nishida H (2006) Geological notes on plant fossil localities of the Ligorio Márquez Formation, central Patagonia, Chile. In: Nishida H (ed) Post-Cretaceous Floristic Changes 29 in Southern Patagonia, Chile. Chuo University, Tokyo, pp 29–35

Zachos JC, Dickens GR, Zeebe RE (2008) An early Cenozoic perspective on greenhouse warming and carbon-cycle dynamics. Nature 451:279–283

Zachos JC, McCarren H, Murphy B, Röhl, U, Westerhold T (2010) Tempo and scale of late Paleocene and early Eocene carbon isotope cycles: implications for the origin of hyperthermals. Earth Planet Sci Let 299:242–249

Zachos JC, Pagani M, Sloan IC, Thomas E, Billups K (2001) Trends, rhythms, and aberrations in global climate 65 Ma to present. Science 292:686–693

Zamaloa M del C, Andreis RR (1995) Asociacion palinologia del Paleocene temprano (Formacion Salamanca) in Ea. Laguna Manantiales, Santa Cruz, Argentina. VI Cong Argent Paleontol Bioestrat Actas:301–305

Zamaloa M del C, Gandolfo MA, González CC, Romero DJ, Cúneo NR, Wilf P (2006) Casuarinaceae from the Eocene of Patagonia, Argentina. Internatl J Plant Sci 167(6):1279–1289

Zimicz AN (2012) Ecomorfología de los marsupiales paleógenos de América del Sur. Unpublished PhD thesis, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata, 454 pp

Acknowledgments

It is with great pleasure and gratitude that we acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Peter Wilf and Dr. Viviana Barreda in helping with paleobotanical matters; Dr. Silvio Casadio aided in guiding Woodburne to relevant geological literature; and Drs. Darin Croft, Christine Janis, and Jussi Eronen provided valuable insights regarding mammalian ecofacies. These individuals do not necessarily agree with the interpretations presented here. Many thanks are offered to Marcela Tomeo for the design of several of the figures that illustrate this work. Two anonymous reviewers made valuable comments that improved the manuscript. Wilf and Iglesias gratefully acknowledge support from NSF grant DEB 0919071. F. Goin, M. Bond, A. Carlini, J. Gelfo, A. Iglesias, and N. Zimicz (PIP 0361) thank the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET, Argentina) for its support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix I

Appendix I

Paleogene South American stratigraphy, mammalian faunas, and biochronology

Paleogene

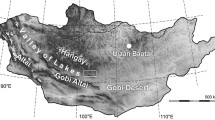

As indicated in Fig. 1, the Paleogene begins at about 65.6 Ma, and lasts until about 23 Ma. The age and magnetic polarity signatures for the Epochs and Stages follows Luterbacher et al. (2004: fig. 20.4). The Sparnacian has been added, following the recommendations of Thiry et al. (2006). The paleotemperature curve is after Zachos et al. (2001).

Oldest Mammal Fauna

The Grenier Farm site is the currently oldest occurrence of a South American therian mammal for which the age is well documented (Goin et al. 2006a). This site has produced only a single (metatherian) taxon: Cocatherium lefipanum, from the Lefipán Formation, Chubut Province, Patagonia. Based on the associated marine invertebrate fauna the Grenier Farm Fauna is considered to be of Danian age. The position shown on Fig. 1 reflects the 5 m separation of the Grenier Farm site above the likely position of the K/Pg boundary (Goin et al. 2006a: fig. 2).

Tiupampan SALMA

The Tiupampan SALMA is recognized in the Santa Lucia Formation of Bolivia (Gayet et al. 1991). Whereas this unit is not found in Patagonia, it is here taken as older than the Peligran SALMA of that region, following Gelfo et al. (2009).

The Tiupampa Fauna is found in the middle part of the Santa Lucía Formation of Bolivia (Fig. 1; 12, Fig. 2b). Marshall et al. (1997) and Sempere et al. (1997) reviewed the stratigraphy of the Santa Lucía Formation and associated strata. The Santa Lucía Formation is underlain by the El Molino Formation (?late Campanian; Maastrichtian—Danian) and unconformably overlain by the Cayara Formation (Thanetian equivalent). All of the Upper El Molino, the Santa Lucía and part of the Cayara formations are of reversed polarity, correlated to Chron C26r, or from 61.7–58.7 Ma in Luterbacher et al. 2004). The El Molino-Santa Lucía contact is correlated with a regression coeval with the Danian-Selandian boundary at 61.7 Ma, and with the base of chron C26r. Regarding the Tiupampan, this fauna is associated with the base of the Middle Santa Lucía Formation, for which an increase in grain size of the sediments is interpreted (Sempere et al. 1997) as a regression. The first major regression within chron C26r is near the top of the Selandian, or ca 59 Ma. This suggests that the Tiupampa SALMA is about 59 Ma old = very late Selandian; see also Marshall et al. (1997).

Mammal biochronology suggests an earlier age for the Tiupampan. The relative ages of the Peligran (Bonaparte et al. 1993) and Tiupampan (Pascual and Ortiz-Jaureguizar 1990) SALMAs have been revised by Gelfo et al. (2009). Qualitative analyses suggested that the Tiupampan is older than the Peligran, and may be phyletically closer to those of early Puercan age in North America. Molinodus is a member of the Panameriungulatan subfamily Kollpaniinae in the Tiupampa Fauna, and may represent an early dispersal event from North to South America (Muizon and Cifelli 2000: 145), perhaps of Puercan age. As summarized by Gayet et al. (1991) most metatherian and eutherian groups are permissive of an early Paleocene (essentially Puercan) age of many Tiupampan taxa, but Alcedidorbignya (Pantodonta) is first known in the Torrejonian of North America. A late Puercan to Torrejonian correlation for the Tiupampan is shown in Fig. 1, at about 64 Ma.

This scenario implies that the reversed magnetic polarity with which the Tiupampa Fauna is associated pertains to Chron 28r, rather than 26r (also Gelfo et al. 2009), and that the regression interpreted from the presence of coarse-grained material in the Tiupampa sediments is open to interpretations other than reflecting a global event.

On one hand, Sempere et al. (1997:719 L) indicated that the nonmarine sediments of the basal part of the Santa Lucía Formation reflect an eustatically-controlled regression, without tectonic influence. On the other hand, Sempere et al. (1997:715 L) portrayed the distribution of the red-brown lacustrine mudstones of the lower Santa Lucía Formation as having been controlled by remaining subsidence of the basin and by the structural framework in which they occur. This suggests a local, rather than regional, cause for these deposits and diminishes the interpretation for an eustatic origin. Thus, notwithstanding the proposed correlation of the Santa Lucía sediments with Chron C26r, there appears to be no compelling reason to equate the base of the Santa Lucía Formation with the Danian-Selandian boundary.