Abstract

Despite advances in knowledge about human lactation, clinicians face many problems when advising mothers who are experiencing breastfeeding difficulties that do not respond to normal management strategies. Primary insufficient milk production is now being acknowledged, but incidence rates have not been well studied. Many women have known histories of infertility, polycystic ovary syndrome, obesity, hypertension, insulin resistance, thyroid dysfunction, hyperandrogenism or other hormonal imbalances, while others have no obvious risk factors. Some present with obviously abnormal breasts that are pubescent, tuberous/tubular or asymmetric in shape, raising the question of insufficient mammary gland tissue. Other women have breasts that appear within normal limits yet do not lactate normally. Endocrine disruptors may underlie some of these cases but their impact on human milk production has not been well explored. Similarly, any problem with prolactin such as a deficiency in serum prolactin or receptor number, receptor resistance, or poor bioavailability or bioactivity could underlie some cases of insufficient lactation, yet these possibilities are rarely investigated. A weak or suppressed milk ejection reflex, often assumed to be psychosomatic, could be related to thyroid dysfunction or caused by downstream post-receptor pathway problems. In the absence of sufficient data regarding these situations, desperate mothers may turn to non-evidence-based remedies, sometimes at considerable cost and unknown risk. Research targeted to these clinical dilemmas is critical in order to develop evidence-based strategies and increase breastfeeding duration and success rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

CDC reports that 3,952,841 babies were born in the U.S. in 2012 (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/births.htm)

Clinical symptoms may include excess body hair (hirsutism), adult acne, and/or male-pattern balding (alopecia)

Hyperandrogenism is the excess of one or more male hormones and includes testosterone, dehydrotestosterone (DHT), dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) and androstenedione.

T. Hale, personal communication. http://www.infantrisk.com/content/presence-macroprolactinemia-mothers-insufficient-milk-syndrome

Quinn, E. A. (2014). Who manages the mammaries? http://biomarkersandmilk.blogspot.com/2013/01/who-manages-mammaries.html

References

Saadeh RJ. The baby-friendly hospital initiative 20 years on: facts, progress, and the way forward. J Hum Lact. 2012;28(3):272–5. doi:10.1177/0890334412446690.

Li R, Fein SB, Chen J, Grummer-Strawn LM. Why mothers stop breastfeeding: mothers’ self-reported reasons for stopping during the first year. Pediatrics. 2008;122 Suppl 2:S69–76. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-1315i.

Odom EC, Li R, Scanlon KS, Perrine CG, Grummer-Strawn L. Reasons for earlier than desired cessation of breastfeeding. Pediatrics. 2013;131(3):e726–32. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-1295.

Brown CR, Dodds L, Legge A, Bryanton J, Semenic S. Factors influencing the reasons why mothers stop breastfeeding. Can J Public health. 2014;105(3):e179–85.

Olang B, Heidarzadeh A, Strandvik B, Yngve A. Reasons given by mothers for discontinuing breastfeeding in Iran. Int Breastfeed J. 2012;7(1):7. doi:10.1186/1746-4358-7-7.

Hurst N. Recognizing and treating delayed or failed lactogenesis II. J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2007;52(6):588–94.

West D, Marasco L. The breastfeeding mother’s guide to making more milk. McGraw Hill Professional; 2009.

Stuebe AM, Horton BJ, Chetwynd E, Watkins S, Grewen K, Meltzer-Brody S. Prevalence and risk factors for early, undesired weaning attributed to lactation dysfunction. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2014. doi:10.1089/jwh.2013.4506.

Kent JC, Prime DK, Garbin CP. Principles for maintaining or increasing breast milk production. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2012;41(1):114–21. doi:10.1111/j.1552-6909.2011.01313.x.

Amir L. Breastfeeding: managing ‘supply’ difficulties. Aust Fam Physician. 2006;35(9):686–9.

Flaherman VJ, Hicks KG, Cabana MD, Lee KA. Maternal experience of interactions with providers among mothers with milk supply concern. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2012;51(8):778–84. doi:10.1177/0009922812448954.

Neville MC, Anderson SM, McManaman JL, Badger TM, Bunik M, Contractor N, et al. Lactation and neonatal nutrition: defining and refining the critical questions. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2012;17(2):167–88. doi:10.1007/s10911-012-9261-5.

Spence J. The modern decline of breast-feeding. Br Med J. 1938;2(4057):729–33.

Deem H, McGeorge M. Breastfeeding. N Z Med J. 1958;57:539–56.

Neifert M, DeMarzo S, Seacat J, Young D, Leff M, Orleans M. The influence of breast surgery, breast appearance, and pregnancy-induced breast changes on lactation sufficiency as measured by infant weight gain. Birth. 1990;17(1):31–8.

Neifert MR. Prevention of breastfeeding tragedies. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2001;48(2):273–97.

Schoenberg N. Some mothers can’t breast-feed. Chic Tribune. 2013;3:2013.

Thoma ME, McLain AC, Louis JF, King RB, Trumble AC, Sundaram R, et al. Prevalence of infertility in the United States as estimated by the current duration approach and a traditional constructed approach. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(5):1324–31.e1. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.11.037.

Stanford JB. What is the true prevalence of infertility? Fertil Steril. 2013;99(5):1201–2. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.12.006.

Chandra A, Copen CE, Stephen EH. Infertility and impaired fecundity in the United States, 1982–2010: data from the national survey of family growth. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2013;67:1–18.

ESHRE/ASRM. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Hum Reprod. 2004;19(1):41–7.

Sirmans SM, Pate KA. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Epidemiol. 2013;6:1–13. doi:10.2147/clep.s37559.

Gambineri A, Pelusi C, Vicennati V, Pagotto U, Pasquali R. Obesity and the polycystic ovary syndrome. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26(7):883–96. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0801994.

Vrbikova J, Hainer V. Obesity and polycystic ovary syndrome. Obes Facts. 2009;2(1):26–35. doi:10.1159/000194971.

Singla R, Gupta Y, Khemani M, Aggarwal S. Thyroid disorders and polycystic ovary syndrome: an emerging relationship. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19(1):25–9. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.146860.

Gaberscek S, Zaletel K, Schwetz V, Pieber T, Obermayer-Pietsch B, Lerchbaum E. Mechanisms in endocrinology: thyroid and polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;172(1):R9–21. doi:10.1530/eje-14-0295.

Torris C, Thune I, Emaus A, Finstad SE, Bye A, Furberg AS, et al. Duration of lactation, maternal metabolic profile, and body composition in the Norwegian EBBA I-study. Breastfeed Med. 2013;8(1):8–15. doi:10.1089/bfm.2012.0048.

Vanky E, Nordskar J, Leithe H, Hjorth-Hansen A, Martinussen M, Carlsen S. Breast size increment during pregnancy and breastfeeding in mothers with polycystic ovary syndrome: a follow-up study of a randomised controlled trial on metformin versus placebo. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03449.x.

Nommsen-Rivers LA, Dolan LM, Huang B. Timing of stage II lactogenesis is predicted by antenatal metabolic health in a cohort of primiparas. Breastfeed Med. 2012;7(1):43–9. doi:10.1089/bfm.2011.0007.

Routh C H F. Infant feeding and its influence on life, or, The causes and prevention of infant mortality. William Wood & Co.; 1879.

Dimitrakakis C, Bondy C. Androgens and the breast. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11(5):212. doi:10.1186/bcr2413.

Kochenour NK. Lactation suppression. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1980;23(4):1045–59.

Betzold CM, Hoover KL, Snyder CL. Delayed lactogenesis II: a comparison of four cases. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2004;49(2):132–7. doi:10.1016/j.jmwh.2003.12.008.

Vanky E, Isaksen H, Moen MH, Carlsen SM. Breastfeeding in polycystic ovary syndrome. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87(5):531–5. doi:10.1080/00016340802007676.

Carlsen SM, Jacobsen G, Vanky E. Mid-pregnancy androgen levels are negatively associated with breastfeeding. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89(1):87–94. doi:10.3109/00016340903318006.

Soltani H, Arden M. Factors associated with breastfeeding up to 6 months postpartum in mothers with diabetes. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs : JOGNN / NAACOG. 2009;38(5):586–94. doi:10.1111/j.1552-6909.2009.01052.x.

Hummel S, Hummel M, Knopff A, Bonifacio E, Ziegler AG. [Breastfeeding in women with gestational diabetes]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2008;133(5):180–4. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1017493.

Lemay DG, Ballard OA, Hughes MA, Morrow AL, Horseman ND, Nommsen-Rivers LA. RNA sequencing of the human milk Fat layer transcriptome reveals distinct gene expression profiles at three stages of lactation. PLoS One. 2013. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0067531.

Neville MC, Webb P, Ramanathan P, Mannino MP, Pecorini C, Monks J, et al. The insulin receptor plays an important role in secretory differentiation in the mammary gland. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;305(9):E1103–14. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00337.2013.

Thatcher SS, Jackson EM. Pregnancy outcome in infertile patients with polycystic ovary syndrome who were treated with metformin. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(4):1002–9. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.09.047.

Abascal K, Yarnell E. Botanical galactagogues. Altern Complement Ther. 2008;14(6):288–94.

Stein I, Leventhal M. Amenorrhea associated with bilateral polycystic ovaries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1935;29:181–91.

Stein I. Bilateral polycystic ovaries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1945;50:385–96.

Stein IF, Cohen MR, Elson R. Results of bilateral ovarian wedge resection in 47 cases of sterility; 20 year end results; 75 cases of bilateral polycystic ovaries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1949;58(2):267–74.

Balcar V, Silinkova-Malkova E, Matys Z. Soft tissue radiography of the female breast and pelvic pneumoperitoneum in the stein-leventhal syndrome. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh). 1972;12(3):353–62.

Cruz-Korchin N, Korchin L, Gonzalez-Keelan C, Climent C, Morales I. Macromastia: how much of it is fat? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109(1):64–8.

Marasco L, Marmet C, Shell E. Polycystic ovary syndrome: a connection to insufficient milk supply? J Hum Lact. 2000;16(2):143–8.

Wojcicki JM. Maternal prepregnancy body mass index and initiation and duration of breastfeeding: a review of the literature. J Women’s Health. 2011;20(3):341–7.

Nader S. Polycystic ovary syndrome and the androgen-insulin connection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165(2):346–8.

Rasmussen K, Kjolhede C. Prepregnant overweight and obesity diminish the prolactin response to suckling. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5):1388.

Clark NM, Podolski AJ, Brooks ED, Chizen DR, Pierson RA, Lehotay DC, et al. Prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome phenotypes using updated criteria for polycystic ovarian morphology: an assessment of over 100 consecutive women self-reporting features of polycystic ovary syndrome. Reprod Sci. 2014;21(8):1034–43. doi:10.1177/1933719114522525.

Palomba S, Falbo A, Russo T, Tolino A, Orio F, Zullo F. Pregnancy in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: the effect of different phenotypes and features on obstetric and neonatal outcomes. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(5):1805–11. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.10.043.

Soules MR, Sherman S, Parrott E, Rebar R, Santoro N, Utian W, et al. Executive summary: stages of reproductive aging workshop (STRAW). Climacteric. 2001;4(4):267–72.

Wang Y, Tanbo T, Åbyholm T, Henriksen T. The impact of advanced maternal age and parity on obstetric and perinatal outcomes in singleton gestations. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284(1):31–7.

Crawford NM, Steiner AZ. Age-related infertility. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. 2015;42(1):15–25. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2014.09.005.

Marquis GS, Penny ME, Diaz JM, Marin RM. Postpartum consequences of an overlap of breastfeeding and pregnancy: reduced breast milk intake and growth during early infancy. Pediatrics. 2002;109(4):e56.

Nommsen-Rivers LA, Chantry CJ, Peerson JM, Cohen RJ, Dewey KG. Delayed onset of lactogenesis among first-time mothers is related to maternal obesity and factors associated with ineffective breastfeeding. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(3):574–84. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2010.29192.

Suzuki S. Maternal age and breastfeeding at 1 month after delivery at a Japanese hospital. Breastfeed Med. 2014;9(2):101–2. doi:10.1089/bfm.2013.0100.

Murase M, Nommsen-Rivers L, Morrow AL, Hatsuno M, Mizuno K, Taki M, et al. Predictors of low milk volume among mothers who delivered preterm. J Hum Lact. 2014;30(4):425–35. doi:10.1177/0890334414543951.

Shermak M. Congenital and Developmental Abnormalities of the Breast. In: Jatoi I, Kaufmann M, editors. Management of Breast Disease. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2010. p. 37–51.

Dewey K, Finley D, Strode M, Lönnerdal B. Relationship of maternal age to breast milk volume and composition. Human Lactation 2. Springer; 1986. p. 263–73.

De Tata V. Age-related impairment of pancreatic beta-cell function: pathophysiological and cellular mechanisms. Front Endocrinol. 2014;5:138. doi:10.3389/fendo.2014.00138.

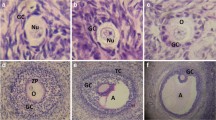

Neifert MR, Seacat JM, Jobe WE. Lactation failure due to insufficient glandular development of the breast. Pediatrics. 1985;76(5):823–8.

Huggins K, Petok E, Mireles O. Markers of Lactation Insufficiency: A Study of 34 Mothers. Curr Issues Clin Lact. 2000:25–35

Arbour MW, Kessler JL. Mammary hypoplasia: not every breast can produce sufficient milk. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2013;58(4):457–61. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12070.

Neifert MR, Seacat JM. Lactation insufficiency: a rational approach. Birth. 1987;14(4):182–8.

Cassar-Uhl D. Finding sufficiency: breastfeeding with insufficient glandular tissue. Amarillo: Praeclarus Press, LLC; 2014.

Lieberman P, Ravichandran P. Breast Surgery Likely to Cause Breastfeeding Problems. National Research Center for Women and Families. 2010.

Andrade RA, Coca KP, Abrao AC. Breastfeeding pattern in the first month of life in women submitted to breast reduction and augmentation. J Pediatr. 2010;86(3):239–44. doi:10.2223/JPED.2002.

Pacifico MD, Kang NV. The tuberous breast revisited. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60(5):455–64. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2007.01.002.

Klinger M, Caviggioli F, Klinger F, Villani F, Arra E, Di Tommaso L. Tuberous breast: morphological study and overview of a borderline entity. Can J Plast Surg = J Can de chirurgie Plast. 2011;19(2):42–4.

Ito O, Kawazoe T, Suzuki S, Muneuchi G, Saso Y, Hamamoto Y, et al. Mammary hypoplasia resulting from hormone receptor deficiency. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(3):975–7.

Guillette EA, Conard C, Lares F, Aguilar MG, McLachlan J, Guillette Jr LJ. Altered breast development in young girls from an agricultural environment. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(3):471–5.

Hansen T. Pesticide exposure deprives Yaqui girls of breastfeeding-- ever. Indian Country Today 2010.

Crain DA, Janssen SJ, Edwards TM, Heindel J, Ho SM, Hunt P, et al. Female reproductive disorders: the roles of endocrine-disrupting compounds and developmental timing. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(4):911–40. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.067.

Neville M, Walsh C. Effects of xenobiotics on milk secretion and composition. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;61(3):687S–94.

Cox DB, Owens RA, Hartmann PE. Blood and milk prolactin and the rate of milk synthesis in women. Exp Physiol. 1996;81(6):1007–20.

O’Brien CE, Krebs NF, Westcott JL, Dong F. Relationships among plasma zinc, plasma prolactin, milk transfer, and milk zinc in lactating women. J Hum Lact. 2007;23(2):179–83. doi:10.1177/0890334407300021.

Koprowski JA, Tucker HA. Serum prolactin during various physiological states and its relationship to milk production in the bovine. Endocrinology. 1973;92(5):1480–7. doi:10.1210/endo-92-5-1480.

Mennella JA, Pepino MY. Breastfeeding and prolactin levels in lactating women with a family history of alcoholism. Pediatrics. 2010;125(5):e1162–70. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-3040.

Iwama S, Welt CK, Romero CJ, Radovick S, Caturegli P. Isolated prolactin deficiency associated with serum autoantibodies against prolactin-secreting cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(10):3920–5. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-2411.

De Bellis A, Colella C, Bellastella G, Lucci E, Sinisi AA, Bizzarro A, et al. Late primary autoimmune hypothyroidism in a patient with postdelivery autoimmune hypopituitarism associated with antibodies to growth hormone and prolactin-secreting cells. Thyroid. 2013;23(8):1037–41. doi:10.1089/thy.2012.0482.

Cooper GS, Bynum ML, Somers EC. Recent insights in the epidemiology of autoimmune diseases: improved prevalence estimates and understanding of clustering of diseases. J Autoimmun. 2009;33(3–4):197–207. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2009.09.008.

Neville MC, Morton J. Physiology and endocrine changes underlying human lactogenesis II. J Nutr. 2001;131(11):3005S–8.

Tyson JE, Hwang P, Guyda H, Friesen HG. Studies of prolactin secretion in human pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1972;113(1):14–20.

López MÁC, Rodríguez JLR, García MR. Chapter 12: Physiological and pathological hyperprolactinemia: can we minimize errors in the clinical practice? Prolactin InTech; 2013.

Callejas L, Berens P, Nader S. Breastfeeding failure secondary to idiopathic isolated prolactin deficiency: report of two cases. Breastfeed Med. 2015. doi:10.1089/bfm.2015.0003.

Lawrence RA, Lawrence RM. Breastfeeding: a guide for the medical profession. 7th ed. Maryland Heights: Elsevier Mosby; 2011. p. 71.

Koukoulis GN. Macroprolactinemia: an unnoticeable factor. Hormones (Athens). 2003;2:91–2.

Chen C-C, Stairs DB, Boxer RB, Belka GK, Horseman ND, Alvarez JV, et al. Autocrine prolactin induced by the Pten–Akt pathway is required for lactation initiation and provides a direct link between the Akt and Stat5 pathways. Genes Dev. 2012;26(19):2154–68.

Auriemma RS, Perone Y, Di Sarno A, Grasso LFS, Guerra E, Gasperi M, et al. Results of a single-center observational 10-year survey study on recurrence of hyperprolactinemia after pregnancy and lactation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(1):372–9. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-3039.

Batrinos ML, Panitsa-Faflia C, Anapliotou M, Pitoulis S. Prolactin and placental hormone levels during pregnancy in prolactinomas. Int J Fertil. 1981;26(2):77–85.

Cheng W, Zhang Z. [Management of pituitary adenoma in pregnancy]. Zhonghua fu chan ke za zhi. 1996;31(9):537–9.

Ingram JC, Woolridge MW, Greenwood RJ, McGrath L. Maternal predictors of early breast milk output. Acta Paediatr. 1999;88(5):493–9.

Hurley WL. Role of prolactin. In: Lactation Biology ANSC 438. University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. 2010. http://ansci.illinois.edu/static/ansc438/Lactation/prolactin.html. Accessed 15 Feb 2015.

Varas SM, Jahn GA. The expression of estrogen, prolactin, and progesterone receptors in mammary gland and liver of female rats during pregnancy and early postpartum: regulation by thyroid hormones. Endocr Res. 2005;31(4):357–70.

Zargar AH, Salahuddin M, Laway BA, Masoodi SR, Ganie MA, Bhat MH. Puerperal alactogenesis with normal prolactin dynamics: is prolactin resistance the cause? Fertil Steril. 2000;74(3):598–600.

Hovey RC, Trott JF, Vonderhaar BK. Establishing a framework for the functional mammary gland: from endocrinology to morphology. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2002;7(1):17–38.

Motil K, Thotathuchery M, Montandon C, Hachey D, Boutton T, Klein P, et al. Insulin, cortisol and thyroid hormones modulate maternal protein status and milk production and composition in humans. J Nutr. 1994;124(8):1248–57.

Miyake A, Tahara M, Koike K, Tanizawa O. Decrease in neonatal suckled milk volume in diabetic women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1989;33(1):49–53.

Speller E, Brodribb W. Breastfeeding and thyroid disease: a literature review. Breastfeed Rev. 2012;20(2):41–7.

Stein M. Failure to thrive in a four-month-old nursing infant. Dev Behav Pediatr. 2002;23(4):S69–73.

Buckshee K, Kriplani A, Kapil A, Bhargava VL, Takkar D. Hypothyroidism complicating pregnancy. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;32(3):240–2.

Marasco L. The impact of thyroid dysfunction on lactation. Breastfeed Abstr. 2006;25(2):9. 11–2.

Capuco AV, Connor EE, Wood DL. Regulation of mammary gland sensitivity to thyroid hormones during the transition from pregnancy to lactation. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2008;233(10):1309–14. doi:10.3181/0803-RM-85.

Capuco AV, Kahl S, Jack LJ, Bishop JO, Wallace H. Prolactin and growth hormone stimulation of lactation in mice requires thyroid hormones. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1999;221(4):345–51.

Hapon MB, Varas SM, Gimenez MS, Jahn GA. Reduction of mammary and liver lipogenesis and alteration of milk composition during lactation in rats by hypothyroidism. Thyroid. 2007;17(1):11–8. doi:10.1089/thy.2005.0267.

Hapon MB, Varas SM, Jahn GA, Gimenez MS. Effects of hypothyroidism on mammary and liver lipid metabolism in virgin and late-pregnant rats. J Lipid Res. 2005;46(6):1320–30. doi:10.1194/jlr.M400325-JLR200.

Hapon MB, Simoncini M, Via G, Jahn GA. Effect of hypothyroidism on hormone profiles in virgin, pregnant and lactating rats, and on lactation. Reproduction. 2003;126(3):371–82.

Brabant G, Beck-Peccoz P, Jarzab B, Laurberg P, Orgiazzi J, Szabolcs I, et al. Is there a need to redefine the upper normal limit of TSH? Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;154(5):633–7. doi:10.1530/eje.1.02136.

Waise A, Price HC. The upper limit of the reference range for thyroid-stimulating hormone should not be confused with a cut-off to define subclinical hypothyroidism. Ann Clin Biochem. 2009;46(Pt 2):93–8. doi:10.1258/acb.2008.008113.

Stagnaro-Green A. Optimal care of the pregnant woman with thyroid disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(8):2619–22.

Negro R, Schwartz ARG, Tinelli A, Mangieri T, Stagnaro-Green A. Increased pregnancy loss rate in thyroid antibody negative women with TSH levels between 2.5 and 5.0 in the first trimester of pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:E44–8.

Joshi JV, Bhandarkar SD, Chadha M, Balaiah D, Shah R. Menstrual irregularities and lactation failure may precede thyroid dysfunction or goitre. J Postgrad Med. 1993;39(3):137–41.

Varas SM, Munoz EM, Hapon MB, Aguilera Merlo CI, Gimenez MS, Jahn GA. Hyperthyroidism and production of precocious involution in the mammary glands of lactating rats. Reproduction. 2002;124(5):691–702.

Geddes DT. The use of ultrasound to identify milk ejection in women – tips and pitfalls. Int Breastfeed J. 2009;4:5. doi:10.1186/1746-4358-4-5.

Hurley WL. Residual Milk. In: Lactation Biology ANSC 438. University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. 2010. http://ansci.illinois.edu/static/ansc438/Lactation/residualmilk.html. Accessed 15 Feb 2015.

Ueda T, Yokoyama Y, Irahara M, Aono T. Influence of psychological stress on suckling-induced pulsatile oxytocin release. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84(2):259–62.

Dewey KG. Maternal and fetal stress are associated with impaired lactogenesis in humans. J Nutr. 2001;131(11):3012S–5.

Baxley SE, Jiang W, Serra R. Misexpression of wingless-related MMTV integration site 5A in mouse mammary gland inhibits the milk ejection response and regulates Connexin43 phosphorylation. Biol Reprod. 2011;85(5):907–15. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.111.091645.

Reichenstein M, Rauner G, Barash I. Conditional repression of STAT5 expression during lactation reveals its exclusive roles in mammary gland morphology, milk-protein gene expression, and neonate growth. Mol Reprod Dev. 2011;78(8):585–96. doi:10.1002/mrd.21345.

Plante I, Wallis A, Shao Q, Laird DW. Milk secretion and ejection are impaired in the mammary gland of mice harboring a Cx43 mutant while expression and localization of tight and adherens junction proteins remain unchanged. Biol Reprod. 2010;82(5):837–47. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.109.081406.

Plante I, Laird DW. Decreased levels of connexin43 result in impaired development of the mammary gland in a mouse model of oculodentodigital dysplasia. Dev Biol. 2008;318(2):312–22. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.03.033.

Muto T, Tien T, Kim D, Sarthy VP, Roy S. High glucose alters Cx43 expression and gap junction intercellular communication in retinal Muller cells: promotes Muller cell and pericyte apoptosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(7):4327–37. doi:10.1167/iovs.14-14606.

Weisskopf E, Fischer CJ, Bickle Graz M, Morisod Harari M, Tolsa JF, Claris O, et al. Risk-benefit balance assessment of SSRI antidepressant use during pregnancy and lactation based on best available evidence. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2015;14(3):413–27. doi:10.1517/14740338.2015.997708.

Hernandez LL, Collier JL, Vomachka AJ, Collier R, Horseman N. Suppression of lactation and acceleration of involution in the bovine mammary gland by a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. J Endocrinol. 2011;209(1):45.

Pai VP, Hernandez LL, Stull MA, Horseman ND. The type 7 serotonin receptor, 5-HT(7), is essential in the mammary gland for regulation of mammary epithelial structure and function. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:364746. doi:10.1155/2015/364746.

Horseman ND, Collier RJ. Serotonin: a local regulator in the mammary gland epithelium. Ann Rev Animal Biosci. 2014;2:353–74. doi:10.1146/annurev-animal-022513-114227.

Hernandez LL, Grayson BE, Yadav E, Seeley RJ, Horseman ND. High Fat diet alters lactation outcomes: possible involvement of inflammatory and serotonergic pathways. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e32598. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032598.

Hutcheon JA, Lisonkova S, Joseph KS. Epidemiology of pre-eclampsia and the other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;25(4):391–403. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2011.01.006.

Yabes-Almirante C, Lim CHTN. Enhancement of breastfeeding among hypertensive mothers. Increasingly Saf Success Pregnancies. 1996;12:279–86.

Leeners B, Rath W, Kuse S, Neumaier-Wagner P. Breast-feeding in women with hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. J Perinat Med. 2005;33(6):553–60.

Majumdar S, Dasgupta H, Bhattacharya K, Bhattacharya A. A study of placenta in normal and hypertensive pregnancies. J Anat Soc India. 2005;54(2):7–12.

Gouldsborough I, Black V, Johnson IT, Ashton N. Maternal nursing behaviour and the delivery of milk to the neonatal spontaneously hypertensive rat. Acta Physiol Scand. 1998;162(1):107–14.

Wlodek M, Wescott K, Serruto A, O’Dowd R, Wassef L, Ho P, et al. Impaired mammary function and parathyroid hormone-related protein during lactation in growth-restricted spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Endocrinol. 2003;178(2):233–45.

Haldeman W. Can magnesium sulfate therapy impact lactogenesis? J Hum Lact. 1993;9(4):249–52.

Adams R S, Hutchinson L J, Ishler V A. Trouble shooting problems with low milk production. Penn State Dairy and Animal Science Fact Sheet;1998 98–16.

Jelliffe DB, Jelliffe EF. The volume and composition of human milk in poorly nourished communities. A review. Am J Clin Nutr. 1978;31(3):492–515.

Penagos Tabares F, Bedoya Jaramillo JV, Ruiz-Cortés ZT. Pharmacological overview of galactogogues. Vet Med Int. 2014;2014:602894. doi:10.1155/2014/602894.

Jacobson H. Mother food: food and herbs that promote milk production and mother’s health self-published; 2004

Lamberts SW, Macleod RM. Regulation of prolactin secretion at the level of the lactotroph. Physiol Rev. 1990;70(2):279–318.

Merritt JE, Brown BL. An investigation of the involvement of calcium in the control of prolactin secretion: studies with low calcium, methoxyverapamil, cobalt and manganese. J Endocrinol. 1984;101(3):319–25.

Henly S, Anderson C, Avery M, Hills-Bonuyk S, Potter S, Duckett L. Anemia and insufficient milk in first-time mothers. Birth. 1995;22(2):87–92.

O’Connor DL, Picciano MF, Sherman AR. Impact of maternal iron deficiency on quality and quantity of milk ingested by neonatal rats. Br J Nutr. 1988;60(3):477–85.

Toppare MF, Kitapci F, Senses DA, Kaya IS, Dilmen U, Laleli Y. Lactational failure–study of risk factors in Turkish mothers. Indian J Pediatr. 1994;61(3):269–76.

Dempsey C, McCormick NH, Croxford TP, Seo YA, Grider A, Kelleher SL. Marginal maternal zinc deficiency in lactating mice reduces secretory capacity and alters milk composition. J Nutr. 2012;142(4):655–60. doi:10.3945/jn.111.150623.

Stone LP, Stone PM, Rydbom EA, Stone LA, Stone TE, Wilkens LE, et al. Customized nutritional enhancement for pregnant women appears to lower incidence of certain common maternal and neonatal complications: an observational study. Glob Adv Health Med : Improv Healthcare Outcomes Worldw. 2014;3(6):50–5. doi:10.7453/gahmj.2014.053.

Mortel M, Mehta SD. Systematic review of the efficacy of herbal galactogogues. J Hum Lact. 2013;29(2):154–62. doi:10.1177/0890334413477243.

Budzynska K, Gardner ZE, Low Dog T, Gardiner P. Complementary, holistic, and integrative medicine: advice for clinicians on herbs and breastfeeding. Pediatr Rev / Am Acad Pediatr. 2013;34(8):343–52. doi:10.1542/pir.34-8-343. quiz 52–3.

Garg R, Gupta V. A comparative study on galactogogue property of milk and aqueous decoction of asparagus racemosus in rats. Int J Pharmacogn Phytochem Res. 2010;2(2):36–9.

Bingel A, Farnsworth N. Higher plants as potential sources of galactogogues. Econ Med Plant Res. 1994;6(1–54):2–53.

MacIntosh J. What is the Pharmacological basis for the action of herbs that promote lactation and how can they best be utilized? Part I. Can J Herbalism. 2003;24(4):15–9. 36.

MacIntosh J. What is the Pharmacological basis for the action of herbs that promote lactation and how can they best be utilized? Part II. Can J Herbalism. 2004;25(1):15–21. 38.

Stein J. Afterbirth: it’s what’s for dinner. Time Magazine. 2009 July 3.

Soyková-Pachnerová E, Brutar V, Golová B, Zvolská E. Placenta as a lactagogon. Gynecol Obstet Investig. 1954;138(6):617–27.

Vallone S. The role of subluxation and chiropractic care in hypolactation. J Clin Chiropr Pediatr. 2007;8(1–2):518–24.

Sutherland RC, Juss TS, Wakerley JB. Prolonged electrical stimulation of the nipples evokes intermittent milk ejection in the anaesthetised lactating rat. Exp Brain Res. 1987;66(1):29–34.

Baird A. How to use a TENS unit to aid in lactation. eHow Health 2010.

Smith KL. How do I use a TENS unit to re-lactate? 2015. http://www.breastnotes.com/breastfeeding/BrFd-ReLac-TENS.htm Accessed 15 Feb 2015.

Wang Q, Qiao H, Bai J. Low frequency ultrasound promotes lactation in lactating rats. Nan fang yi ke da xue xue bao = J South Med Univ. 2012;32(5):730–3.

Ayers J. The use of alternative therapies in support of breastfeeding. J Hum Lact. 2000;16(1):52–6.

Yokoyama Y, Ueda T, Irahara M, Aono T. Releases of oxytocin and prolactin during breast massage and suckling in puerperal women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1994;53(1):17–20.

Cowley KC. Psychogenic and pharmacologic induction of the let-down reflex can facilitate breastfeeding by tetraplegic women: a report of 3 cases. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(6):1261–4.

Feher S, Berger L, Johnson J, Wilde J. Increasing breast milk production for premature infants with a relaxation/imagery audiotape. Pediatrics. 1989;83(1):57–60.

Pincus L, editor. Hypnosis: Using the Power of the Mind to Help the Power of the Breast. Annual meeting of the International Lactation Consultant Association. Scottsdale, AZ; 1999.

Singh G, Chouhan R, Kidhu K. Effect of antenatal expression of breast milk at term in reducing breast feeding failures. MJAFI. 2009;65:131–3.

Wang H, An J, Han Y, Huang L, Zhao J, Wei L, et al. Multicentral randomized controlled stuides on acupuncture at Shaoze (SI 1) for treatment of postpartum hypolactation. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2007;27(2):85–8.

Lu P, Zheng J, Zhao Y, Chen J, Huang L. Research advance on tuina and postpartum milk secretion. J Acupunct Tuina Sci. 2009;7(6):375–8.

Wei L, Wang H, Han Y, Li C. Clinical observation on the effects of electroacupuncture at Shaoze (SI 1) in 46 cases of postpartum insufficient lactation. J Trad Chin Med = Chung i tsa chih ying wen pan / sponsored by All-China Association of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2008;28(3):168–72.

He JQ, Chen BY, Huang T, Li N, Bai J, Gu M, et al. Randomized controlled multi-central study on acupuncture at Tanzhong (CV 17) for treatment of postpartum hypolactation. Zhongguo zhen jiu = Chin Acupunct Moxibustion. 2008;28(5):317–20.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the mothers of the Low Milk Supply and IGT Facebook group and the Mothers Overcoming Breastfeeding Issues (MOBI) listserv for their generosity in sharing their stories and photos for this article. I would also like to express my gratitude to Dr. Russ Hovey for help with the preparation of this manuscript as well as his many insights into individual situations that have helped sharpen my understanding of the physiology of lactation; progress cannot be made without such collaboration across the fields and disciplines.

Conflict of interest

The author declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marasco, L.A. Unsolved Mysteries of the Human Mammary Gland: Defining and Redefining the Critical Questions from the Lactation Consultant’s Perspective. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 19, 271–288 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10911-015-9330-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10911-015-9330-7