Abstract

Structural and cultural barriers have led to limited access to and use of mental health services among immigrants in the United States (U.S.). This study provided a systematic review of factors associated with help-seeking attitudes, intentions, and behaviors among immigrants who are living in the U.S. This systematic review was performed using Medline, CINAHL, APA PsycInfo, Global Health, and Web of Science. Qualitative and quantitative studies examining mental help-seeking among immigrants in the U.S. were included. 954 records were identified through a search of databases. After removing duplicates and screening by title and abstract, a total of 104 articles were eligible for full-text review and a total of 19 studies were included. Immigrants are more reluctant to seek help from professional mental health services due to barriers such as stigma, cultural beliefs, lack of English language proficiency, and lack of trust in health care providers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), mental health is defined as “a state of well-being in which an individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community” [1] p1]. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) in 2020 reported that 21% (52.9 million) of adults aged 18 or older experienced one mental illness [2]. Also, the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the lives of Americans and adversely affected their mental health [3]. During the pandemic, 40.0% of U.S. adults experienced one or more economic stressors and 27.8% had probable depression [4]. In addition, more than one out of four U.S. adults showed symptoms of serious mental distress during the pandemic. These high rates of mental distress have clinical implications for mental health and well-being, including seeking professional care services. Notably, finding accessible mental health care was difficult before the pandemic for many Americans. This challenge was exacerbated by stay‐at‐home orders and stress due to the rising number of COVID-19 deaths in health care settings [5,6,7].

According to the U.S. Census Bureau report, individuals in a racial minority communities will account for more than half of the population by 2044 which will make the U.S. a majority-minority country [8]. New American Economy reported that more than 44.7 million immigrants were living in the U.S. in 2019 [9]. Although underrepresented minority groups showed a greater tendency to develop anxiety, depression, and somatic disorders, there are contradictory findings about this greater tendency [10,11,12]. For example, Arab Americans reported higher levels of depression and anxiety compared to the U.S-born Arab Americans while U.S-born Latinos showed higher rates of mental issues than Latino immigrants [13, 14].

Mental health concerns among asylum seekers and refugees in the U.S. are becoming an increasing public health issue as this population rises [15, 16]. Besides, undocumented immigrants are more likely to experience mental disorders due to additional stressors such as unpaid salaries, limited institutional supports, forced labor, and legal issues [16,17,18]. Mental problems among minorities also may result in increasing disability, reducing quality of life, and rising premature death rates, which are linked to the huge cost of care and economic loss [19]. Therefore, a thorough and multi-disciplinary approach is needed to focus on immigrants’ mental needs including overcoming obstacles for seeking mental care [15, 20, 21].

The mental help-seeking process may be affected by different factors such as individual, social, and cultural aspects [22]. Professional or formal mental health services can be provided by a wide array of mental health professionals, while nonprofessional or informal services may be provided by family members, relatives, friends, and online resources. Immigrants are less likely to seek professional services than U.S. born due to various factors [23,24,25]. For example, a review study highlighted the importance of cultural barriers such as stigma, acculturation issues, preferences for non-clinical treatments, and lack of trust in formal mental health care. They also indicated significant barriers to access including English language fluency, limited awareness of mental health services, high cost of mental health services, lack of health insurance, and limited access to professional services among U.S. immigrants [23].

Understanding accessibility and utilization of mental care services such as facilitators and barriers is essential to ensure that these services meet immigrants’ needs. There have been review studies targeted at a specific immigration group in the U.S., including Asian Americans, East Asians, and Muslims [26,27,28]. Some review studies were not established based on theories; hence, some challenges may arise with the interpretation of the results, understanding the relationships of variables, and conceptualizing of the mental help-seeking process [29,30,31,32]. Furthermore, there are unique characteristics in the U.S. due to its culture and language diversity. This diverse population offers a suitable context to add evidence on differences and similarities of mental help-seeking process among various cultural groups. Categorizing factors associated with help-seeking process based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) may elucidate areas of focus to develop coherent interventions and new standards. In addition, by meticulously looking at the unique cultural values among immigrants, culturally appropriate interventions can be designed and implemented to facilitate this process. Many scholars also have recommended conducting studies on seeking mental health services among U.S. immigrants due to inconsistent findings across diverse cultural groups [23, 24, 28, 33,34,35]. Therefore, this systematic review study aimed to draw an appropriate framework to explore associated factors with mental help-seeking attitudes, intentions, and behaviors based on TPB constructs among U.S. immigrants.

Theoretical Framework

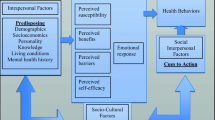

Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) was used to develop a theoretical foundation for the aims of this systematic review. TPB is considered as an extension of the Theory of Reasoned Action [36]. Figure 1 shows the constructs of TPB, which proposes that an individual’s attitudes toward a behavior, subjective norms associated with the behavior, and perceived control over the behavior are important cognitive predictors of intentions to do the behavior [37]. For example, negative attitudes toward seeking mental services were related to decreased help-seeking behavior [38,39,40,41]. Subjective norms are defined as “the perceived pressure from or approval by significant others for performing a certain behavior” [42] p3]. Subjective norms have a significant role due to the higher rate of stigma toward mental issues [43,44,45,46,47]. Also, behavioral control is a very important element that determines intention since an adequate control over individuals’ behaviors leads them to perform their intentions [36]. Behavioral control is essential since seeking mental care is not totally voluntary and affected by a variety of factors such as language proficiency, time, mental care cost, knowledge about availability, and awareness of the new cultural expectations [26, 48,49,50]. The need of theory-based mental health studies using theoretical frameworks were also recommended by previous researchers [41, 51, 52].

Theory of planned behavior (TPB) [37]

Methods

Search Strategy

This systematic review was performed using a comprehensive search through Medline, CINAHL, APA PsycInfo, Global Health, and Web of Science, locating articles published between January 2011 and April 2021. The Zotero bibliography software was used to collect and manage the references [53]. The results of this systematic review are reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [54]. Appropriate MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms were applied to find relevant articles to the topic based on PICO elements (Population, Intervention, Outcome). Search terms and identified records are shown in Appendix A.

Eligibility Criteria

Table 1 indicates the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this systematic review.

Quality Assessment of Studies

The quality of cross-sectional, experimental, and qualitative studies was evaluated by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [55,56,57]. To determine the risk of bias, we evaluated 8 domains for cross-sectional, 13 domains for the Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT), 9 domains for the quasi-experimental, and 10 domains for qualitative studies. Each domain was assessed to determine the potential for high-risk bias (No = 0), low-risk bias (Yes = 1), unclear bias (U). The quality of mixed-method studies was assessed by Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) including five items based on “Yes”, “No”, and “Cannot tell” responses [58]. For cross-sectional studies, a 6 or above were considered “good” quality, 5 or 4 were “fair” quality, and below 4 were “poor”. For RCTs, an 8 or above were considered “good” quality. A 5 or above were “good” quality for the quasi-experimental study. For qualitative studies, an 8 or above were considered “good” quality. For mixed-method studies, a 3 or above were considered “good” quality and below 3 was “fair” quality.

Results

Study Selection

Of the initial 954 records identified through searching databases, after removing duplicates and screening titles and abstracts, a total of 104 articles were eligible for the full-text review. A total of 19 studies met the eligibility criteria and 85 studies were excluded. Figure 2 shows the PRISMA Flow Diagram of the search strategy.

PRISMA flow diagram of Search Strategy. Note. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analyses flow diagram [54]

Study Characteristics

Fourteen studies used quantitative designs, of which 12 were cross-sectional [59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70] and two were experimental [71, 72]. Three studies used qualitative designs [73,74,75] and two studies used a mixed-methods design [76, 77]. Tables 2 and 3 summarize the study characteristics, study instruments, and descriptive results.

Major Findings

An adapted conceptual framework of determinants of professional mental help-seeking addressed by included studies based on constructs of the TPB (Fig. 3). Many of the studies showed consistent findings about participants’ willingness to seek mental care services from family members and friends as the primary frontline support to individuals with mental issues [60,61,62, 65, 68, 70, 73, 74, 76, 77].

Regarding sociodemographic characteristics, age, gender, education, and income were factors associated with the mental help-seeking process. Some studies indicated that females were more likely to seek professional mental care compared to males [60, 71, 77]. However, one study showed that female Chinese Americans were more reluctant to seek mental help from physicians compared to males. They showed that although females are more willing to seek advice for their mental problems, they prefer to seek help from their friends and relatives who speak their language [70]. There were also inconsistent findings about the association of age with the help-seeking process. Although there was no significant relationship between age and mental help-seeking attitudes among Chinese Americans [60], Bhutanese immigrants 45 years and older reported mental care access challenges more frequently than other age groups among [62]. In addition, higher levels of education and income [59, 62, 63, 67, 70, 71] and having health insurance facilitated seeking mental care [65, 74, 76].

Table 4 summarizes the facilitators of the mental help-seeking process using TPB constructs. Among subjective norms that are important factors in collectivistic cultures [78], a lower level of stigma was a significant facilitator of seeking professional mental care [59, 60, 63, 67, 75, 76]. Conversely, while there was no association between individual stigma toward clinical high-risk phase for psychosis defined as “a clinical syndrome denoting a risk for overt psychosis” [79] p2] and help-seeking attitudes, family stigma was unpredictably related to more positive attitudes among Chinese and Taiwanese immigrants. Possibly, issues and behaviors that require professional help include those that are threatening to an individual’s social group, and not personal experiences of mental distress or general interpersonal issues [71]. To assess the perceived behavioral control, a lower level of mental distress and more access to counselling services facilitated seeking mental care [61, 62, 67, 72, 73, 75]. Also, immigrants with long working hours, having difficulty involved in taking leave, and unavailable transportation services were less likely to seek treatment due to insufficient time [74, 75]. To assess attitudes toward seeking mental help, favorable beliefs and perceptions about mental health have facilitated seeking professional help [74, 75].

Study Quality

Among 14 studies with quantitative designs, 12 cross-sectional studies were of “good” quality [59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70]. All three qualitative studies were of “good” quality [73,74,75]. Also, of two mixed-method studies, one study was considered as “good” quality [76] and one was “fair” quality [77]. Two experimental studies were of “good” quality [71, 72]. All cross-sectional studies received high scores for clear definition of inclusion criteria and use of valid and reliable measurement tools. However, half of the cross-sectional studies did not identify confounding factors which may affect the relationships of main study outcomes. Among two experimental studies, the RCT study failed to blind participants and assessors [72] and the quasi-experimental study failed to consider a control group and multiple measurements of the outcome before and after the intervention [71]. Overall, all qualitative studies used appropriate strategies for research methodology and the interpretation of results. One of the mixed-method studies also failed to get a good score due to the inadequate integration of qualitative and quantitative findings as well as insufficient explanations about inconsistencies between qualitative and quantitative results [77].

Discussion

We conducted this systematic review to examine factors related to professional mental help-seeking attitude, intention, and behavior among immigrants, asylum seekers, and refugees living in the U.S. using the TPB constructs. Our results highlighted the importance of informal help-seeking behaviors across all included studies. Similarly, previous studies also found that the acculturation orientation might considerably affect help-seeking preferences when an immigrant maintains traditional and cultural beliefs [80,81,82,83]. Acculturation orientations is “the maintenance of one’s culture of origin and the extent to which minority groups actively participate in the mainstream culture” [83] p2]. For example, people from Asian cultures preferred to get help from family and friends since seeking professional help is considered shameful and a violation of family coherence [84]. Likewise, there was a negative relationship between Asian cultural values and positive mental help-seeking attitudes [85]. Conversely, no significant relationship between acculturation levels and professional mental help-seeking attitudes was found among Iranian Americans due to improving knowledge about mental issues, reducing stigma, and more available resources [86]. Our findings also emphasized the significance of acculturation levels and traditional values to address the mental help-seeking process and implement interventions due to the complexity of help-seeking behaviors among diverse immigrant groups.

TPB Constructs

Among subjective norms as an essential component of TPB, acculturation levels and cultural beliefs affected the process of mental help-seeking. Our results indicated that factors such as longer years of residence in the U.S., and a higher level of English proficiency helped immigrants to be more acculturated to the U.S. Furthermore, more acculturated immigrants were more likely to seek professional mental help. Our findings also highlighted the importance of the stigma as a topmost barrier to seeking professional help. Similarly, previous research revealed that the stigma negatively affected help-seeking attitudes and behaviors among western Muslims based on their cultural heritage [87]. Vietnamese Americans also showed a higher level of mental illness stigma that resulted in being worried and fearful of break in confidentiality and the feelings of embarrassment and shame, consequently making them less likely to seek professional care [82, 88]. The critical role of stigmatizing attitudes directly or indirectly has been addressed among Asian Americans [26, 89], Muslims [28, 87], Filipino [90], and Latin American [91].

Another important component of TPB is perceived behavior control [36]. According to our findings, more access to mental care services, availability of interpreters, and culturally appropriate services were facilitators of the professional help, especially among refugees and asylum seekers [92]. Indeed, if mental health providers establish a trusting relationship without any biased attitudes and negative emotional impacts, immigrants tend to seek mental care [92, 93]. Also, the detrimental impact of cultural incompetence of professional mental help resources was addressed by several studies [92, 94]. Providing mental care based on the patient’s preferred language is especially important as mental care services rely greatly upon verbal interactions for communicating important information including complicated emotions, experiences, and symptoms [92, 95]. Also, access to bilingual mental care providers and interpreter facilities lessen the linguistic mismatch between patients to develop a trusting relationship without judgmental behaviors [10]. Despite existing evidence on important advantages of using bilingual mental health workers, their multidimensional roles and contributions remain underrecognized and need future research [92]. Not only cultural differences but also institutional and organizational policies in health care facilities limited access to mental care services [32].

The attitude toward professional mental help-seeking is considered a key construct of TPB. Our findings showed that favorable attitudes and positive beliefs about professional mental help-seeking and perceptions of mental care helped immigrants to understand the importance of appropriate services. Conversely, financial instability may prevent them from seeking care, as similarly mentioned by previous studies [96, 97]. Also, consistent with our results, studies among Asian Americans revealed important roles of stigmatizing attitudes, previous experiences of mental health services, and cultural mistrust [98, 99].

Our findings indicated that sociodemographic characteristics are important to study the mental help-seeking process due to their relationships with TPB constructs. Based on our results, women are more proactive to seek professional mental health care services due to their favorable opinions of professional help-seeking [80, 86]. Additionally, traditional gender roles can lead to this difference between men and women in terms of help-seeking behaviors. For example, a sense of being more independent among males may foster a greater perceived risk that results in a low self-esteem and inability to manage their mental issues [99]. However, some studies found no relationship between gender and mental help-seeking endorsement [89, 100]. A higher level of education also may facilitate the mental help-seeking process which is consistent with previous studies [86, 101].

In general, U.S. immigrants reported a combination of barriers and facilitators to seek professional mental care services, thus supporting the idea that associated factors with seeking care play important roles in the context of improving mental health. Although all 19 studies were conducted among U.S. immigrants who share a similar context, each specific group follow their own traditional, cultural, and religious beliefs. It is unrealistic to think that immigrants will engage in mental care activities out of their cultural beliefs as the potential impacts of these beliefs were discussed. Therefore, culturally based measures should be taken based on the situation, context, and challenges immigrants face. Also, reducing stigma toward mental illnesses using multidisciplinary community-based approaches highlights the significance of facilitating this process from sociocultural to organizational aspects.

Limitations of Findings

This systematic review has led to significant findings. However, some limitations should be noted. The majority of included quantitative studies used convenience sampling to recruit participants which restricts the generalizability of findings [102]. Most of the studies also used a cross-sectional design that limits the ability to make a causal inference [103]. In addition, self-report data may pose concerns about the social desirability and recall biases [104]. Although all studies mentioned the geographic areas for data collection, none of them discussed geographic accessibility as a barrier or facilitator of mental help-seeking. Most included studies also were not guided by theoretical or conceptual frameworks and failed to measure participants’ mental status which could be an important factor to seek mental treatment.

Implications for Research and Practice

Findings of this review suggest key research gaps that need to be addressed in future research among immigrants. Table 5 indicates implications for research and practice.

Conclusions

According to the findings of the systematic review of 19 studies to evaluate factors associated with mental help-seeking among immigrants in the U.S., it is obvious that immigrants receive insufficient mental care. The current systematic review shows the importance of understanding socioeconomic features, subjective norms, acculturation, perceived behavioral control, and attitudes that affect seeking mental care services. Also, language barriers, lack of trust for the health providers, limited social support, and length of residence in the U.S. may predict the help-seeking process.

References

World Health Organization. Strengthening mental health promotion. Mental Health, Switzerland, 2018. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response

SAMHSA, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, National Survey on Drug Use and Health | CBHSQ Data. (n.d.). Retrieved November 9, 2022, from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/nsduh-national-survey-drug-use-and-health

Holingue C, Badillo-Goicoechea E, Riehm KE, Veldhuis CB, Thrul J, Johnson RM, et al. Mental distress during the COVID-19 pandemic among US adults without a pre-existing mental health condition: findings from American trend panel survey. Prev Med. 2020;139: 106231.

Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, Sampson L, Vivier PM, Galea S. Low assets and financial stressors associated with higher depression during COVID-19 in a nationally representative sample of US adults. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2021;75(6):501–8.

Twenge JM, Joiner TE. Mental distress among US adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Psychol. 2020;76(12):2170–82.

Kochhar R, Bennett J. Immigrants in U.S. experienced higher unemployment in the pandemic but have closed the gap. Pew Research Center, 2020. Available from: Retrieved February 23, 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/07/26/immigrants-in-u-s-experienced-higher-unemployment-in-the-pandemic-but-have-closed-the-gap/

Lee JO, Kapteyn A, Clomax A, Jin H. Estimating influences of unemployment and underemployment on mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: who suffers the most? Public Health. 2021;201:48–54.

Colby S, Ortman JM. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060. Population Estimates and Projections. Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau, 2015. Available from: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Projections-of-the-Size-and-Composition-of-the-U.S.-Colby-Ortman/09c9ad858a60f9be2d6966ebd0bc267af5a76321

New American Economy. Immigrants and the economy. United States, 2019. https://www.newamericaneconomy.org/locations/national/

Rice AN, Harris SC. Issues of cultural competence in mental health care. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2021;61(1):e65–8.

Bas-Sarmiento P, Saucedo-Moreno MJ, Fernández-Gutiérrez M, Poza-Méndez M. Mental health in immigrants versus native population: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2017;31(1):111–21.

Turrini G, Purgato M, Ballette F, Nosè M, Ostuzzi G, Barbui C. Common mental disorders in asylum seekers and refugees: umbrella review of prevalence and intervention studies. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2017;11:51.

Pampati S, Alattar Z, Cordoba E, Tariq M, Mendes de Leon C. Mental health outcomes among Arab refugees, immigrants, and U.S. born Arab Americans in Southeast Michigan: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):379.

Alegría M, Canino G, Shrout PE, Woo M, Duan N, Vila D, et al. Prevalence of mental illness in immigrant and non-immigrant US Latino groups. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(3):359–69.

World Health Organization. Mental health and forced displacement. Mental Health, Switzerland, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2022, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-and-forced-displacement

Breslau J, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Borges G, Kendler KS, Su M, Kessler RC. Risk for psychiatric disorder among immigrants and their US-born descendants: evidence from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195(3):189–95.

Jannesari S, Hatch S, Prina M, Oram S. Post-migration social-environmental factors associated with mental health problems among asylum seekers: a systematic review. J Immigr Minor Health. 2020;22(5):1055–64.

Song SJ, Kaplan C, Tol WA, Subica A, de Jong J. Psychological distress in torture survivors: pre- and post-migration risk factors in a US sample. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(4):549–60.

World Health Organization. Investing in mental health: evidence for action. Mental Health Innovation Network, Switzerland, 2014. https://www.mhinnovation.net/resources/investing-mental-health-evidence-action

World Health Organization. Mental health action plan 2013–2020. Switzerland, 2013. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/89966/1/9789241506021_eng.pdf

Lake J, Turner MS. Urgent need for improved mental health care and a more collaborative model of care. Perm J. 2017;21:17–024.

World Health Organization [WHO]. Promoting mental health: concepts, emerging evidence, practice: summary report. Switzerland, 2004. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42940

Derr AS. Mental health service use among immigrants in the United States: a systematic review. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(3):265–74.

Bauldry S, Szaflarski M. Immigrant-based disparities in mental health care utilization. Socius. 2017;3:2378023116685718.

De Luna MJF, Kawabata Y. The role of enculturation on the help-seeking attitudes among Filipino Americans in Guam. Int Perspect Psychol Res Pract Consult. 2020;9(2):84–95.

Kim SB, Lee YJ. Factors associated with mental health help-seeking among Asian Americans: a systematic review. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021:1–22.

Na S, Ryder AG, Kirmayer LJ. Toward a culturally responsive model of mental health literacy: facilitating help-seeking among East Asian immigrants to North America. Am J Community Psychol. 2016;58(1–2):211–25.

Amri SB. Mental health help-seeking behaviors of Muslim immigrants in the United States: overcoming social stigma and cultural mistrust. J Muslim Mental Health. 2012;7(1).

Selkirk M, Quayle E, Rothwell N. A systematic review of factors affecting migrant attitudes towards seeking psychological help. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2014;25(1):94–127.

Ahmadinia H, Eriksson-Backa K, Nikou S. Health-seeking behaviors of immigrants, asylum seekers and refugees in Europe: a systematic review of peer-reviewed articles. J Doc. 2021;78(7):18–41.

Satinsky E, Fuhr DC, Woodward A, Sondorp E, Roberts B. Mental health care utilisation and access among refugees and asylum seekers in Europe: a systematic review. Health Policy. 2019;123(9):851–63.

O’Mahony J, Donnelly T. Immigrant and refugee women’s post-partum depression help-seeking experiences and access to care: a review and analysis of the literature. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2010;17(10):917–28.

van der Boor CF, White R. Barriers to accessing and negotiating mental health services in asylum seeking and refugee populations: The application of the candidacy framework. J Immigr Minor Health. 2020;22(1):156–74.

Satyen L, Rogic AC, Supol M. Intimate partner violence and help-seeking behaviour: a systematic review of cross-cultural differences. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019;21(4):879–92.

Shishehgar S, Gholizadeh L, DiGiacomo M, Davidson PM. The impact of migration on the health status of Iranians: an integrative literature review. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2015;15(1):20.

Ajzen I, Madden TJ. Prediction of goal-directed behavior: attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1986;22(5):453–74.

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211.

Roness A, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. Help-seeking behavior in patients with anxiety disorder and depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;111(1):51–8.

Miller MJ, Yang M, Hui K, Choi N-Y, Lim RH. Acculturation, enculturation, and Asian American college students’ mental health and attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. J Couns Psychol. 2011;58(3):346–57.

Masuda A, Suzumura K, Beauchamp KL, Howells GN, Clay C. United States and Japanese college students’ attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. Int J Psychol. 2005;40(5):303–13.

Loya F, Reddy R, Hinshaw SP. Mental illness stigma as a mediator of differences in Caucasian and South Asian college students’ attitudes toward psychological counseling. J Couns Psychol. 2010;57(4):484.

Lee J-Y, Shin Y-J. Using the theory of planned behavior to predict Korean college students’ help-seeking intention. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2022;49(1):76–90.

Lee S, Lee MTY, Chiu MYL, Kleinman A. Experience of social stigma by people with schizophrenia in Hong Kong. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186(2):153–7.

Yang LH, Kleinman A. ‘Face’ and the embodiment of stigma in China: the cases of schizophrenia and AIDS. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(3):398–408.

Li X-H, Zhang T-M, Yau YY, Wang Y-Z, Wong Y-LI, Yang L, et al. Peer-to-peer contact, social support and self-stigma among people with severe mental illness in Hong Kong. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2021;67(6):622–31.

Chen SX, Mak WWS, Lam BCP. Is it cultural context or cultural value? Unpackaging cultural influences on stigma toward mental illness and barrier to help-seeking. Soc Psychol Pers Sci. 2020;11(7):1022–31.

Miville ML, Constantine MG. Cultural values, counseling stigma, and intentions to seek counseling among Asian American college women. Couns Values. 2007;52(1):2–11.

Mak HW, Davis JM. The application of the theory of planned behavior to help-seeking intention in a Chinese society. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(9):1501–15.

Porter M, Haslam N. Predisplacement and postdisplacement factors associated with mental health of refugees and internally displaced persons: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2005;294(5):602–12.

Pumariega AJ, Rothe E, Pumariega JB. Mental health of immigrants and refugees. Community Ment Health J. 2005;41(5):581–97.

Nam SK, Chu HJ, Lee MK, Lee JH, Kim N, Lee SM. A meta-analysis of gender differences in attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. J Am Coll Health. 2010;59(2):110–6.

Wills TA, Gibbons FX. Commentary: using psychological theory in help-seeking research. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2009;16(4):440–4.

Zotero. Your personal research assistant. 2019. Retrieved from https://www.zotero.org/

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group TP. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLOS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Sears K, Sfetcu R, Currie M, Qureshi R, Mattis P, Lisy K, Mu P-F. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (eds). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI, 2020. Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global

Tufanaru C, Munn Z, Aromataris E, Campbell J, Hopp L. Chapter 3: Systematic reviews of effectiveness. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. JBI, 2020. Retrieved from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global

Lockwood C, Munn Z, Porritt K. Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):179–87.

Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inf. 2018;34(4):285–91.

Yee T, Ceballos P, Diaz J. Examining the psychological help-seeking attitudes of Chinese immigrants in the US. Int J Adv Couns. 2020;42(3):307–18.

Yee T, Ceballos P, Lawless A. Help-seeking attitudes of Chinese Americans and Chinese immigrants in the United States: the mediating role of self-stigma. J Multicult Couns Dev. 2020;48(1):30–43.

Jang Y, Chiriboga DA, Park NS, Yoon H, Cho YJ, Hong S, et al. The role of self-rated mental health in seeking professional mental health services among older Korean immigrants. Aging Ment Health. 2021;25(7):1332–7.

MacDowell H, Pyakurel S, Acharya J, Morrison-Beedy D, Kue J. Perceptions toward mental illness and seeking psychological help among Bhutanese refugees resettled in the U.S. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2020;41(3):243–50.

Khan FK. Evaluation of factors affecting attitudes of Muslim Americans toward seeking and using formal mental health services. J Muslim Ment Health. 2019;13(2).

Tuazon VE, Gonzalez E, Gutierrez D, Nelson L. Colonial mentality and mental health help-seeking of Filipino Americans. J Couns Dev. 2019;97(4):352–63.

Kim-Mozeleski JE, Tsoh JY, Gildengorin G, Cao LH, Ho TB, Kohli S, et al. Preferences for depression help-seeking among Vietnamese American adults. Community Ment Health J. 2018;54(6):748–56.

Moreno O, Nelson T, Cardemil E. Religiosity and attitudes towards professional mental health services: analysing religious coping as a mediator among Mexican origin Latinas/os in the southwest United States. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2017;20(7):626–37.

Yorke CB, Voisin DR, Baptiste D. Factors related to help-seeking attitudes about professional mental health services among Jamaican immigrants. Int Soc Work. 2016;59(2):293–304.

Schwartz B, Bernal D, Smith L, Nicolas G. Pathways to understand help-seeking behaviors among Haitians. J Immigrant Minority Health. 2014;16(2):239–43.

Keeler AR, Siegel JT, Alvaro EM. Depression and help seeking among Mexican–Americans: the mediating role of familism. J Immigr Minor Health. 2014;16(6):1225–31.

Leung P, Cheung M, Tsui V. Help-seeking behaviors among Chinese Americans with depressive symptoms. Soc Work. 2012;57(1):61–71.

He E, Eldeeb SY, Cardemil EV, Yang LH. Psychosis risk stigma and help-seeking: attitudes of Chinese and Taiwanese residing in the United States. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2020;14(1):97–105.

Hernandez MY, Organista KC. Entertainment-education? A fotonovela? A new strategy to improve depression literacy and help-seeking behaviors in at-risk immigrant Latinas. Am J Community Psychol. 2013;52(3–4):224–35.

Poudel-Tandukar K, Jacelon CS, Chandler GE, Gautam B, Palmer PH. Sociocultural perceptions and enablers to seeking mental health support among Bhutanese refugees in Western Massachusetts. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2019;39(3):135–45.

Kwong K, Chung H, Cheal K, Chou JC, Chen T. Disability beliefs and help-seeking behavior of depressed Chinese American patients in a primary care setting. J Soc Work Disabil Rehabil. 2012;11(2):81–99.

Callister LC, Beckstrand RL, Corbett C. Postpartum depression and help-seeking behaviors in immigrant Hispanic women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2011;40(4):440–9.

Ta Park VM, Goyal D, Nguyen T, Lien H, Rosidi D. Postpartum traditions, mental health, and help-seeking considerations among Vietnamese American women: a mixed-methods pilot study. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2017;44(3):428–41.

Caplan S, Buyske S. Depression, help-seeking and self-recognition of depression among Dominican, Ecuadorian and Colombian immigrant primary care patients in the Northeastern United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(9):10450–74.

Mo PKH, Mak WWS. Help-seeking for mental health problems among Chinese: the application and extension of the theory of planned behavior. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44(8):675–84.

del Re EC, Spencer KM, Oribe N, Mesholam-Gately RI, Goldstein J, Shenton ME, et al. Clinical high risk and first episode schizophrenia: auditory event-related potentials. Psychiatry Res. 2015;231(2):126–33.

Markova V, Sandal GM, Pallesen S. Immigration, acculturation, and preferred help-seeking sources for depression: comparison of five ethnic groups. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):648.

Obasi EM, Leong FTL. Psychological distress, acculturation, and mental health-seeking attitudes among people of African descent in the United States: a preliminary investigation. J Couns Psychol. 2009;56(2):227–38.

Luu TD, Leung P, Nash SG. Help-seeking attitudes among Vietnamese Americans: the impact of acculturation, cultural barriers, and spiritual beliefs. Soc Work Ment Health. 2009;7(5):476–93.

Dimitrova R, Aydinli-Karakulak A. Acculturation orientations mediate the link between religious identity and adjustment of Turkish-Bulgarian and Turkish-German adolescents. Springerplus. 2016;5(1):1024.

Han M, Pong H. Mental health help-seeking behaviors among Asian American Community College students: the effect of stigma, cultural barriers, and acculturation. J Coll Stud Dev. 2015;56(1):1–14.

Sun S, Hoyt WT, Brockberg D, Lam J, Tiwari D. Acculturation and enculturation as predictors of psychological help-seeking attitudes (HSAs) among racial and ethnic minorities: a meta-analytic investigation. J Couns Psychol. 2016;63(6):617–32.

Vahdat R. Cultural values and acculturation factors affecting help-seeking in Iranian Americans [dissertation]. Alliant International University; 2021.

Zia B, Mackenzie CS. Internalized stigma negatively affects attitudes and intentions to seek psychological help among western Muslims: testing a moderated serial mediation model. Stigma Health. 2021.

Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, Maggioni F, Evans-Lacko S, Bezborodovs N, et al. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol Med. 2015;45(1):11–27.

Tummala-Narra P, Li Z, Chang J, Yang EJ, Jiang J, Sagherian M, et al. Developmental and contextual correlates of mental health and help-seeking among Asian American college students. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2018;88(6):636–49.

Martinez AB, Co M, Lau J, Brown JSL. Filipino help-seeking for mental health problems and associated barriers and facilitators: a systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2020;55(11):1397–413.

Dueweke AR, Bridges AJ. The effects of brief, passive psychoeducation on suicide literacy, stigma, and attitudes toward help-seeking among Latino immigrants living in the United States. Stigma Health. 2017;2(1):28–42.

Fennig M, Denov M. Interpreters working in mental health settings with refugees: an interdisciplinary scoping review. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2021;91(1):50–65.

Bontempo K, Malcolm K. An Ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure: educating interpreters about the risk of vicarious trauma in healthcare settings. In: Swabey L, Malcolm K, editors. In our hands. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press; 2012. p. 105–30.

McCann TV, Mugavin J, Renzaho A, Lubman DI. Sub-Saharan African migrant youths’ help-seeking barriers and facilitators for mental health and substance use problems: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):275.

Rousseau C, Measham T, Moro M-R. Working with interpreters in child mental health. Child Adolesc Mental Health. 2011;16(1):55–9.

Hall JC, Conner KO, Jones K. The strong Black Woman versus mental health utilization: a qualitative study. Health Soc Work. 2021;46(1):33–41.

Kirmayer LJ, Narasiah L, Munoz M, Rashid M, Ryder AG, Guzder J, et al. Common mental health problems in immigrants and refugees: general approach in primary care. CMAJ. 2011;183(12):E959–67.

Wei M, Heppner PP, Mallen MJ, Ku T-Y, Liao KY-H, Wu T-F. Acculturative stress, perfectionism, years in the United States, and depression among Chinese international students. J Couns Psychol. 2007;54(4):385–94.

Vogel DL, Wester SR, Larson LM. Avoidance of counseling: psychological factors that inhibit seeking help. J Couns Dev. 2007;85(4):410–22.

Wendt D, Shafer K. Gender and attitudes about mental health help seeking: results from National Data. Health Soc Work. 2016;41(1):e20–8.

Steele LS, Dewa CS, Lin E, Lee KLK. Education level, income level and mental health services use in Canada: associations and policy implications. Healthc Policy. 2007;3(1):96–106.

Andrade C. The inconvenient truth about convenience and purposive samples. Indian J Psychol Med. 2021;43(1):86–8.

Savitz DA, Wellenius GA. Can cross-sectional studies contribute to causal inference? It depends. Am J Epidemiol. 2022.

Althubaiti A. Information bias in health research: definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:211.

Registration

This study has been registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), registration number CRD42021252005.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose. The systematic review research did not involve human participants or animal. Obtaining informed consents is not needed for this review study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix A: Search terms and identified records

Appendix A: Search terms and identified records

Date | Database | Search terms P | Search terms O | N | Duplicates identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

4.20.2021 | Medline | (Migrant OR immigrant OR refugee OR asylum seekers) | 31,541 | ||

Limits: English | |||||

Date: 2011–2021 | |||||

4.20.2021 | Medline | (Migrant OR immigrant OR refugee OR asylum seekers) | (MH: help seeking OR help-seeking) AND (mental health OR mental illness OR mental problems OR mental issues OR mental distress OR mental disorders OR psychological problems OR psych*issues OR psych* distress OR psych*illness OR psych* disease OR depression OR depressive symptoms OR anxiety disorders OR stress OR schizophrenia OR bipolar OR phobia OR mania OR personality disorders OR somatic symptom disorders OR post-traumatic OR posttraumatic OR PTSD OR psychosis OR psychiatric) | 153 | |

Limits: English | |||||

Date: 2011–2021 | |||||

4.20.2021 | CINAHL | (Migrant OR immigrant OR refugee OR asylum seekers) | 22,615 | ||

Limits: English | |||||

Date: 2011–2021 | |||||

4.20.2021 | CINAHL | (Migrant OR immigrant OR refugee OR asylum seekers) | (MH: help seeking OR help-seeking) AND (mental health OR mental illness OR mental problems OR mental issues OR mental distress OR mental disorders OR psychological problems OR psych*issues OR psych* distress OR psych*illness OR psych* disease OR depression OR depressive symptoms OR anxiety disorders OR stress OR schizophrenia OR bipolar OR phobia OR mania OR personality disorders OR somatic symptom disorders OR post-traumatic OR posttraumatic OR PTSD OR psychosis OR psychiatric) | 172 | 80 |

Limits: English | |||||

Date: 2011–2021 | |||||

4.20.2021 | APA Psycinfo | (Migrant OR immigrant OR refugee OR asylum seekers) | 25,824 | ||

Limits: English | |||||

Date: 2011–2021 | |||||

4.20.2021 | APA Psycinfo | (Migrant OR immigrant OR refugee OR asylum seekers) | (MH: help seeking OR help-seeking) AND (mental health OR mental illness OR mental problems OR mental issues OR mental distress OR mental disorders OR psychological problems OR psych*issues OR psych* distress OR psych*illness OR psych* disease OR depression OR depressive symptoms OR anxiety disorders OR stress OR schizophrenia OR bipolar OR phobia OR mania OR personality disorders OR somatic symptom disorders OR post-traumatic OR posttraumatic OR PTSD OR psychosis OR psychiatric) | 228 | 117 |

Limits: English | |||||

Date: 2011–2021 | |||||

4.20.2021 | Global Health | (Migrant OR immigrant OR refugee OR asylum seekers) | 12,153 | ||

Limits: English | |||||

Date: 2011–2021 | |||||

4.20.2021 | Global Health | (Migrant OR immigrant OR refugee OR asylum seekers) | (MH: help seeking OR help-seeking) AND (mental health OR mental illness OR mental problems OR mental issues OR mental distress OR mental disorders OR psychological problems OR psych*issues OR psych* distress OR psych*illness OR psych* disease OR depression OR depressive symptoms OR anxiety disorders OR stress OR schizophrenia OR bipolar OR phobia OR mania OR personality disorders OR somatic symptom disorders OR post-traumatic OR posttraumatic OR PTSD OR psychosis OR psychiatric) | 27 | 22 |

Limits: English | |||||

Date: 2011–2021 | |||||

4.20.2021 | Web of Science | (Migrant OR immigrant OR refugee OR asylum seekers) | 109,021 | ||

Limits: English | |||||

Date: 2011–2021 | |||||

4.20.2021 | Web of Science | (Migrant OR immigrant OR refugee OR asylum seekers) | (MH: help seeking OR help-seeking) AND (mental health OR mental illness OR mental problems OR mental issues OR mental distress OR mental disorders OR psychological problems OR psych*issues OR psych* distress OR psych*illness OR psych* disease OR depression OR depressive symptoms OR anxiety disorders OR stress OR schizophrenia OR bipolar OR phobia OR mania OR personality disorders OR somatic symptom disorders OR post-traumatic OR posttraumatic OR PTSD OR psychosis OR psychiatric) | 374 | 173 |

Limits: English | |||||

Date: 2011–2021 | |||||

Total items from databases: 954 | |||||

Total duplicates removed: 392 | |||||

Total items from databases after duplicates removed: 562 | |||||

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohammadifirouzeh, M., Oh, K.M., Basnyat, I. et al. Factors Associated with Professional Mental Help-Seeking Among U.S. Immigrants: A Systematic Review. J Immigrant Minority Health 25, 1118–1136 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-023-01475-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-023-01475-4