Abstract

The medical-legal partnership addresses social and political determinants of health. Yet, relatively little is known about best practices for these two service providers collaborating to deliver integrated services, particularly to im/migrant communities. To investigate evaluations of existing medical-legal partnerships in order to understand how they function together, what they provide, and how they define and deliver equitable, integrated care. We searched five databases (PubMed, Medline, Web of Science, HeinOnline, and Nexus Uni) using search terms related to “medical-legal partnerships”, “migrants”, and “United States”. We systematically evaluated ten themes related to how medical and legal teams interacted, were situated, organized, and who they served. Articles were published in English between 2010 and 2019; required discussion about a direct partnership between medical and legal professionals; and focused on providing clinical care and legal services to im/migrant populations. Eighteen articles met our inclusion criteria. The most common form of partnership was a model in which legal clinics make regular referrals to medical clinics, although the reverse was also common. Most services were not co-located. Partnerships often engaged in advocacy work, provided translation services, and referred clients to non-medical providers and legal services. This review demonstrates the benefits of a legal-medical partnership, such as enhancing documentation and care for im/migrants and facilitating a greater attention to political determinants of health. Yet, this review demonstrates that, despite the increasing salience of such partnership, few have written up their lessons learned and best practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Immigrants face extraordinary challenges as they make a living in the United States [1]. The challenges are not only social—learning new ways in which people think, work, and interact—but they are also political. The contemporary politics of the Trump Administration are not new. Xenophobia and alienation, despite a long-standing and robust U.S. dependence on immigrant labor, are centuries old. In this article, we take stock of a critically important health intervention that recognizes how political factors promote good health: the medical-legal partnership.

The 44.7 million immigrants in the United States represent about 14% of the total population [2]—around one-quarter are undocumented [3] and nearly half of these individuals are uninsured [4]. Institutional challenges are rampant throughout U.S. health systems, from immigrants facing language barriers and high out-of-pocket expenditures (with or without insurance coverage), to healthcare workers, from clerks to clinicians, who do not take into account the unique cultural and structural needs in providing care for immigrant patients [1]. Other challenges include legal dimensions. For instance, how does immigration status—authorized or unauthorized, refugee, asylee—affect what type of care someone can seek and from where? On the other hand, clinicians offer psychological evaluations, which may legitimize immigrants’ suffering in legal processes. These health evaluations are often very important in asylum status claims given they are based on a well-founded fear of persecution in their home country based on race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion [5]. Yet, asylum is difficult to obtain and most applicants are rejected [5].

People immigrate to the U.S. for different reasons, from war, interpersonal violence, and political threat to economic depravity. Even within countries, many immigrants carry with them different histories, beliefs, and needs [6]. This creates a variety of health needs for those who arrive to the U.S.—from acute psychiatric care to longer-term chronic concerns [7]. Although psychiatric care is critical for people who have faced extraordinary trauma from, for example, human trafficking or political violence, psychiatric care without legal and financial assistance falls short. During legal evaluations of asylum cases, medical professionals evaluate asylum seekers for the physical and psychological effects of trauma and to provide critical evidence corroborating the asylum seeker’s testimony. This process requires coordination among medical and legal professionals, but rarely are medical and legal teams situated to work together and organize the evidence from medical evaluations into asylum legal proceedings. Similarly, medical professionals assist in cases of human trafficking, in which victims are eligible for immigration relief [8]. Yet, many immigrants live in U.S. communities in which enforcement practices surrounding unauthorized status create a climate of fear, resulting in both acute and chronic psychological stress that manifests in poor physical and mental health [9].

What a medical-legal partnership should look like is a critical question for addressing the overlapping health and legal needs in immigrant populations. A medical-legal partnership is a model in which “…an attorney is embedded into the healthcare facility or team and works alongside providers to screen for and treat social and legal issues that negatively affect health and that cannot be resolved through medical care alone [10].” Although this understanding of a medical-legal partnership places lawyers in a medical clinic, it is also common for medical and legal professionals to collaborate in an informal capacity through regular referrals—formalized or ad hoc—between medical and legal clinics [11].

This paper investigates existing forms of medical-legal partnerships that demonstrate how medical and legal professionals work together to meet the unique needs of immigrants. We systematically evaluate articles that were published in the last decade and address how medical professionals and lawyers coordinate to provide medical and legal services for immigrants, refugees, and asylees. We evaluate structures and logistical operations of the partnerships, the scope of available services, and the strategies used to address the sensitive nature of care for these socially and politically vulnerable populations in order to identify gaps in existing models of care and opportunities for future collaborations among medical and legal professionals.

Methods

Selection Criteria

We took an interdisciplinary approach by searching academic databases from medical and legal fields to ensure that we collected articles about medical-legal partnerships written from both medical and legal perspectives. We searched for articles published only in the past ten years (2010–2019) to focus on existing partnerships and those that focus on “direct” partnerships. A “direct” partnership involves a continuous interaction and collaboration between medical and legal professionals, including cases of co-located services. Direct partnerships include legal professionals making regular referrals to medical professionals (or vice versa), or medical and legal professionals collaborating to discuss strategies to improve services. In doing so, we followed the reporting guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) Statement [12].

We had clear inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria for this review include articles published: in peer-reviewed academic journals (IC1), in English (IC2), between 2010 and 2019 (IC3), that discuss direct partnerships between health care providers and legal professionals (IC4), that do not discuss historical partnerships that ceased operations before 2000 (IC5), that discuss the provision of clinical care (IC6), that focus on the U.S. im/migrant population (IC7), and that have independent discussion of medical-legal partnerships (IC8).

We excluded articles that did not focus on current medical-legal partnerships, clinical care (e.g., focused on biomedical research), and im/migrant populations in the United States. A plethora of different kinds of medical-legal partnerships focus on services for veterans, former inmates, or other vulnerable groups, and these partnerships operate under different constraints that those that support the im/migrant population. Articles on medical-legal partnerships that accept migrants as clients but focus more broadly on community health were also excluded. Finally, we excluded articles that implicitly (rather than explicitly) addressed medical-legal partnerships.

Information Sources

We searched in October 2019 three medical (PubMed, Web of Science, and MedLine) and two legal (HeinOnline and Nexis Uni) databases. We used the search strings for database searches listed in Appendix. Articles were filtered for publication between 2010 and 2019 and publication in English. These search terms and filters were adapted to each database’s search engine.

We followed the following four phases in selecting articles for our systematic review: (1) remove duplicate articles; (2) review remaining titles and screen based on inclusion criteria; (3) review remaining abstracts (or full texts without available abstracts) and exclude based on inclusion criteria; and (4) review remaining full texts.

To facilitate reviews of full articles, we collectively developed 42 questions, grouped into ten sections, that addressed (1) medical-legal interaction; (2) medical services; (3) legal services; (4) medical professionals; (5) additional services; (6) cultural or structural competence; (7) population demographics; (8) logistics; (9) expansion of current work; and (10) the context in which the partnership existed. The term “medical” conveys both physical and mental health professionals. We systematically reviewed each full article according to all 42 questions. The first author reviewed each article and discussed them with the last author; she discussed any articles that were unclear with the full panel of authors. We coded responses as “one” if a theme emerged and “zero” if the theme was absent. Emergent themes that diverged from the analysis framework were recorded as “other” and we recorded detailed notes. When themes could be relevant for medical or legal services in the partnership, answers were considered if they were applicable to the medical services, legal services, or both (e.g. Cultural Competence Question 1 in Table 2). Themes were only coded when the article provided clear details about each theme; for example, if the authors stated they used trauma-informed care but did not explain how the care was delivered, the theme was not recorded because it did not relate to theme delivery. We summed the number of themes reported as yes, no, or other. For some articles, we had multiple positive responses, demonstrating the amount in which one article represented our analysis framework (e.g. in answer to Medical Services Question 1, an article could receive a positive response to both “internal medicine services” and “mental health services” if the partnership provided both). Results demonstrate these key themes as they relate to questions about what common features make up existing models of medical-legal partnerships.

Results

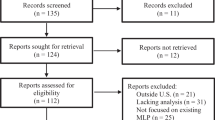

Figure 1 shows that we found 222 articles in our initial search of five databases, including 79 from Nexis Uni, 50 from PubMed, 43 from HeinOnline, 30 from Web of Science, and 20 from MedLine. We removed 66 duplicates and an additional 100 articles using titles and abstracts. Of the 100 articles, we removed 57 because they did not discuss a direct partnership between medical and legal professionals, 29 because they did not focus on the im/migrant population in the United States, 11 because they did not discuss clinical care, two because they only peripherally mentioned medical-legal partnership, and one because it described a partnership that ceased operation before 2000 (see Fig. 1). Of the remaining 56 articles, we excluded 38: 14 did not discuss direct partnerships between medical and legal professionals, 23 did not focus on im/migrant populations, and one because it did not independently discuss medical-legal partnerships (see Fig. 1). We excluded most of the full text articles reviewed because they lacked a real focus on a partnership between legal and medical professionals; for instance, they mentioned the need for legal professionals but did not consult any, or legal professionals expressing concern for the health of their clients without interacting with medical professionals. We found 18 articles met our inclusion criteria.

Flow chart of article selection based on the PRISMA guidelines [12]

Published between 2013 and 2019, twelve articles were retrieved from medical databases and six from legal databases. Seven assessed an existing medical-legal partnership and eleven provided recommendations for such a partnership based on the expertise of physicians, lawyers, and other stakeholders, such as clients and patients. Of the seven existing partnerships that were described, three were located in New York and one each was located in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, California, and Connecticut.

We found lawyers commonly referred clients to medical clinics (often for asylum evaluations), but physicians also frequently referred patients to legal clinics. Eleven partnerships between physicians and lawyers lacked a shared physical site of care, and seven partnerships provided co-located services. No partnerships involved medical teams residing on-site in an existing legal clinic. Five of the seven co-located partnerships involved lawyers visiting existing medical clinics on a routine basis to provide on-site legal services; two of these partnerships were considered joint medical-legal organizations because all patients received legal services from the legal teams alongside their medical care. The other three partnerships referred patients to the visiting legal teams when needed. One of the seven partnerships with co-located services employed a psychiatric nurse to screen clients on-site at the legal clinic for mental health needs; these clients were then referred to specialists for further care. The last of the seven articles describing co-located services discussed the potential for joint medical-legal organizations in which the medical and legal professionals provide co-located services and both the medical and legal professionals are employed by the partnership.

Partnership Characteristics

Table 1 describes frequencies of topics discussed. All articles addressed why the partnership was established, defined the partnership model, and designated roles for legal and medical staff. Other common themes were (1) the general types of medical services provided, (2) how the partnership may provide benefit to clients’ legal status, (3) the asylum evaluation process, (4) consideration of culture in care, (5) the role of trauma in care, (6) clinical needs among particular populations receiving care, (7) strategies used to make services accessible, and (8) funding sources. No articles addressed alternative or specific therapies available for medical care or what happened beyond their partnership for care-seekers (see Table 1).

Table 2 shows most partnerships prepared medical evidence for legal needs and described the asylum evaluation process. Often internists or other non-psychiatric medical specialists prepared psychological evaluations, although mental health professionals conducted these evaluations when available. All partnerships concluded that the joint work was a positive step for the immigrants they served, often citing that they found clients were perceived as more eligible for immigration relief. Most articles indicated direct language translation services were provided (see Table 2).

Figure 2 shows all articles that discussed the interaction of medical and legal services, and partnerships utilizing multiple strategies for integrating services. Nine articles discussed lawyers referring clients to healthcare providers, six discussed healthcare providers referring patients to lawyers, and three discussed a case management system. Three articles described medical and legal services as offered together, and six discussed integrating medical and legal services in other ways (see Fig. 2). Figure 3 shows other common services, including advocacy and awareness raising for partnerships’ clients (n = 6), social services (n = 4), and general educational services, such as private tutoring (n = 2). One article recommended that lawyers engage with local schools to design policies and services that are beneficial to children from immigrant communities; another described a Youth Enrichment Program that organizes soccer games, field trips, and other extracurricular activities for participating children. Families are also assisted to enroll in available health insurance programs and public schools through the program, and referrals are made to services that could aid families with cultural adaptation. No partnerships provided assistance for clients seeking employment and six articles made no mention of services other than medical and legal services.

Half of the articles did not mention cultural or structural competence. Figure 4 shows strategies described in those that did promote cultural and structural competence: translation services to clients (n = 8); training for participating medical and legal professionals on cultural awareness during the provision of services (n = 4); and partnership coordination with traditional healers, community health workers, and other providers that are integrated in communities (n = 2). One article recruited staff from migrant populations. Six articles noted other strategies to provide culturally or structurally competent care (see Fig. 4). These strategies included the use of written guides on cultural competence and peer mentoring. One article recommended hiring providers with prior experience working with immigrant communities and suggested that providers should be as up to date as possible on current affairs to understand the shifting context surrounding migration. Figure 5 shows strategies used to make services accessible: direct translation services for clients (n = 8); referring clients to other accessible healthcare providers and lawyers (n = 8); and providing financial assistance to clients (n = 7). One partnership provided services on-site at schools and local health clinics, and used student-peer advocates, parent nights, and school registration events to advertise available services. No partnerships provided services during expanded hours of operation (see Fig. 5). Three articles did not discuss the accessibility of services.

Discussion

This systematic review describes the complexity and variation in medical-legal partnerships for im/migrant populations in the United States. The overwhelming observation of the review is the significance of these partnerships to improve legal outcomes; ten out of ten articles that discussed the delivery of medical knowledge to legal cases described how people were more likely to receive positive legal outcomes when medical professionals contribute to legal proceedings [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. The legitimatization of trauma and persecution through medical professionals in legal spaces may also be crucial for protecting the lives of migrants who have suffered greatly in both sending and receiving communities alike [13]. Moreover, the finding that people may feel more comfortable disclosing personal trauma and persecution to medical professionals compared to legal professionals suggests these types of partnerships are important for court proceedings as well as for building the best case for individuals seeking asylum. In this way, medical professionals can voice the realities that im/migrants have faced to legitimize their suffering in the face of a legal system that is stacked against them [23].

Educational exchange is at the center of many medical-legal partnerships, although there appeared to be a heavier emphasis on legal professionals educating medical professionals about what is needed from them in such a partnership. Yet in some partnerships, medical professionals provided educational workshops for legal professionals. These bidirectional education exchanges are critical because there is value in both types of knowledge. Lawyers can elevate the work of medical professionals to navigate the legal barriers, terminology, and policies that their patients face—be it through clinical care, court documents, or legal proceedings [13, 10]. Medical professionals provide health- and trauma-informed services and complete legal documents for lawyers who make the legal case for significant impacts of trauma on their clients’ mental and physical health [24]. Such work is critical as many people experience retraumatization during legal interviews, which are required for their cases to court [25]. This retraumatization may lead clients to delay seeking legal relief by avoiding applications and attorneys [26] but it is also one reason medical and legal professionals find their collaboration so critical in the first place [24, 18].

Community-centered care is critical for serving im/migrants [27] and integrating legal and medical services into a physical and professional unit is one positive step toward achieving this critical care. Among many im/migrants communities, the problems they bring to the clinic are not solely medical and often involve social and/or legal concerns [28]. Integrating social and legal services with medical care improves access to care among those most vulnerable. It reduces patient social, financial, and temporal costs by ensuring they have to travel fewer times to the clinic for their multiple health conditions, minimizing the loss of work days due to care-seeking, and reducing social costs such as stigma [29]. Adding legal services to primary and psychiatric services represents a good model of integrated care and ensures a holistic treatment approach [1, 28].While four articles describe specific strategies used for the integration of primary and psychiatric services, including case management systems and standardizing non-psychiatric medical services and mental health services, this review emphasizes that integrated care must incorporate the legal services outlined in these papers. Moreover, the other critical work, such as social services, advocacy and awareness raising, and educational services for clients, must be standard protocol for such integrative services.

Cultural and structural competence in these partnerships is an essential component. Recognizing what people carry with them into the clinic as well as what they need from the clinical engagement is critical. This involves recognizing how and why people may fear, not understand, or reject medical recommendations and the linguistic, cultural, gender, and personal differences between healthcare professional and patients that impede good care. The studies we reviewed emphasize institutional barriers—such as translation services, financial assistance, affordability, and access to psychiatric care—as well as psychiatric barriers, such as having medical professionals trained in trauma-informed care [13,14,15,16, 18, 21, 24, 30].

We were surprised that some themes were missing in these articles. For instance, we projected that more articles would focus on co-location. While co-location is optimal for patients because it means that patients do not have to travel between sites, it also creates more security for people to convey more sensitive information than may appear for legal counsel and avoids causing retraumatization without having psychiatric care on-hand [13, 25]. Having mental health services in the same place as legal services also reduces stigma towards obtaining mental health services. It could also provide educational opportunities for clients in trusted and familiar facilities.

Finally, the lack of follow up from the partnerships about the duration of their collaboration was noteworthy. No discussion of long-term legal and patient outcomes, duration of services through the partnership, success/failure rate of clinical care, or systems in place to support people’s legal and medical needs were provided. Moreover, the lack of follow-up with patients seeking mental health services who had at one point in time also received legal services reveals a gaping hole that exists for understanding both long and short term impacts of pursuing legal services on mental and physical health of im/migrant populations and how medical care can advance legal proceedings.

One limitation of this study is that only seven of 18 articles discussed an existing partnership. So few of these partnerships appear in scholarly publications, despite the fact that they are increasingly common among clinicians and lawyers seeking to address social determinants of health for im/migrants. Ethnographic work that aims to understand the complexities that drive the formation, implementation, organization, and longevity of such projects is vital for their success in the near and long term. In particular, there is a significant knowledge gap around what and how many informal partnerships between small medical and legal practices (local non-small organizations) offer services to asylees, U/T-visa recipients, and refugees; some of which offer coordinated services while others are loosely connected. Unfortunately, neither the practitioners nor the sponsoring organizations publicize their existence beyond word of mouth, and therefore little is known about their organization, contributions, and tireless work in this area.

Conclusion

Medical-legal partnerships are crucial for investing in the mental and physical health of immigrant communities. Because of the fragmentation of the United States health system, many of these projects are ad-hoc and are difficult to implement without revoking the current status quo about how health and medicine are conceived as a problem of the body as opposed to a problem of society. By bringing the trauma and persecution that drive many people to migrate out of the shadows, these medical-legal partnerships can improve the lives of individuals who can benefit from services from lawyers and clinicians alike. They also can elevate the health and well-being of U.S. im/migrant communities. As the consequences of COVID-19 hit these communities, there is no more important time to rethink how our systems are organized and instituted in a country that fails to meet the needs of its most vulnerable people amidst a great pandemic. Indeed, integrating medical and legal services is a good start to rethink how im/migration status is a key social determinant of health and that good health depends on good mental health, personal security, and community solidarity.

References

Castañeda H, Holmes SM, Madrigal DS, Young M-ED, Beyeler N, Quesada J. Immigration as a social determinant of health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:375–92.

U.S. Census Bureau: Selected social characteristics in the United States. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=immigration&hidePreview=true&tid=ACSDP1Y2018.DP02&vintage=2018. Accessed 10 March 2020.

Pew Research Center: U.S. unauthorized immigrant total dips to lowest level in a decade. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2018

Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation: Health coverage and care of undocumented immigrants. San Francisco: Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation; 2019

U.S. Department of Homeland Security: refugees and asylees. https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/Refugees_Asylees_2016.pdf. Accessed 10 March 2020

Castañeda H. Im/migration and health: conceptual, methodological, and theoretical propositions for applied anthropology. NAPA Bulletin. 2010;34(1):6–27.

Mishori R, Aleinikoff S, Davis D. Primary care for refugees: challenges and opportunities. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(2):112–20.

Barber-Rioja V, Garcia-Mansilla A. Special considerations when conducting forensic psychological evaluations for immigration court. J Clin Psychol. 2019;75(11):2049–59.

Fleming PJ, Novak NL, Lopez WD. U.S. immigration law enforcement practices and health inequities. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(6):858–61.

Benfer EA, Gluck AR, Kraschel KL. Medical-legal partnership: lessons from five diverse MLPs in new haven, connecticut. J Law Med Ethics. 2018;46(3):602–9.

Fuller SM, Steward WT, Martinez O, Arnold EA. Medical–legal partnerships to support continuity of care for immigrants impacted by HIV: lessons learned from California. J Immigr Minor Health. 2020;22(1):212–5.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group TP: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLOS Med 2009; 6(7).

Scruggs E, Guetterman TC, Meyer AC, VanArtsdalen J, Heisler M. “An absolutely necessary piece”: a qualitative study of legal perspectives on medical affidavits in the asylum process. J Forensic Leg Med. 2016;44:72–8.

Linton JM, Griffin M, Shapiro AJ, Council on Community Pediatrics: Detention of immigrant children. Pediatrics 2017; 139(5).

Lal P, Phillips M: Discover our model: the critical need for school-based immigration legal services. California Law Review 2018; 106(2):[i]-590.

Asgary R, Smith Clyde L. Ethical and professional considerations providing medical evaluation and care to refugee asylum seekers. Am J Bioethics. 2013;13(7):3–12.

Friley J: Ethics of evidence: Health care professionals in public benefits and immigration proceedings. Yale Journal of Health Policy, Law and Ethics. 2017;17(2).

Yamanis TJ, Zea MC, Monteil AKR, Barker SL, Díaz-Ramirez MJ, Page KR, Martinez O, Rathod J. Immigration legal services as a structural HIV intervention for latinx sexual and gender Minorities. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019;21(6):1365–72.

Asgary R, Charpentier B, Burnett DC. Socio-medical challenges of asylum seekers prior and after coming to the US. J Immigr Minor Health. 2013;15(5):961–8.

Baranowski KA, Moses MH, Sundri J. Supporting asylum seekers: clinician experiences of documenting human rights violations through forensic psychological evaluation. J Trauma Stress. 2018;31(3):391–400.

The Human Rights Initiative at the University at Buffalo. The value of medical students in support of asylum seekers in the United States. Fam Syst Health. 2018;36(2):230–2.

Linton JM, Kennedy E, Shapiro A, Griffin M. Unaccompanied children seeking safe haven: providing care and supporting well-being of a vulnerable population. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2018;92:122–32.

Randolph K: Executive Order 13769 and America's longstanding practice of institutionalized racial discrimination towards refugees and asylum seekers. Stetson Law Review. 2017; 47(1).

Ardalan S. Constructive or counterproductive—benefits and challeneges of integrating mental health professionals into asylum representation. Georgetown Immigrat Law J. 2015;30(1):1–46.

McFadyen G. Memory, language and silence: Barriers to refuge within the British asylum system. J Immigr Refug Stud. 2019;17(2):168–84.

Lustig S. Symptoms of trauma among political asylum applicants: don’t be fooled. Hast Int Comp Law Rev. 2008;31(2):725.

Morris JE. When “patient-centered” is not enough: a call for community-centered medicine. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(1):82–4.

Holmes SM, Hansen H, Jenks A, Stonington SD. Misdiagnosis, mistreatment, and harm—when medical care ignores social forces. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(12):1083–6.

Mendenhall E. Syndemic suffering: social distress, depression, and diabetes among mexican immigrant women. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press; 2014.

Zero O, Kempner M, Hsu S, Haleem H, Toll E, Tobin-Tyler E. Addressing global human rights violations in Rhode Island: the brown human rights asylum clinic. R I Med J Provid. 2019;102(7):17–20.

Funding

We are grateful to the Global Health Initiative at Georgetown University for supporting this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

League, A., Donato, K.M., Sheth, N. et al. A Systematic Review of Medical-Legal Partnerships Serving Immigrant Communities in the United States. J Immigrant Minority Health 23, 163–174 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-020-01088-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-020-01088-1