Abstract

Business growth is often portrayed as an important outcome for small-business owners. Few empirical studies have however examined whether there is a positive relationship between business size and different dimensions of small-business owners’ subjective well-being. In a large cross-sectional sample (n = 1089) of small-business owners from Sweden, we investigate the relationship between business size and the two main components of subjective well-being, life satisfaction and emotional well-being. By means of structural equation modelling, we determine the importance of business size for subjective well-being by focusing on potential advantages (financial satisfaction) and disadvantages (time pressure) related to business size. The results show that there is no overall relationship between business size and life satisfaction, but a weak negative relationship between business size and emotional well-being. However, in a subsequent mediation analyses we find that these findings largely can be explained by the fact that financial satisfaction and time pressure relate to subjective well-being in opposite directions and thus cancel each other out. The results of the mediation analysis also reveal differences across the two components of subjective well-being. We here find that financial satisfaction is more important for small-business owners’ life satisfaction while time pressure is more important for their emotional well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the last decades politicians and policy makers have emphasized the importance of small business growth for the economy and job creation (Morrison et al. 2003; Davidsson 2004; Henrekson and Stenkula 2009). Apart from the societal benefits of growing small-businesses enterprises in general, small-business growth is also commonly viewed as an indicator of continued entrepreneurship (Davidsson 1989, 1991) and a desirable personal outcome for small-business owners owing to its potential association with financial well-being. Davidsson (1989) found that a majority of small-business owners expressed a preference for firm growth both in number of employees as well as in sales. Small-business owners also often express preferences for financial success that in general requires business growth. For instance, Cassar (2007) found direct evidence that preferences for financial success act as an important driver of entrepreneurial growth preferences. However, small-business owners may also perceive that there are potential barriers and disadvantages related to business growth. Previous research has shown that some small-business owners are hesitant to increase their business. For instance, a lack of ownership control, increased financial risks and a heavier workload have been perceived as negative consequences with business growth (Davidsson 1989; Braidford et al. 2017). Previous research also shows that high job demands are prevalent among small-business owners’ and that high demands may be especially pronounced among individuals who owns larger businesses (Nordenmark et al. 2012; Warr 2018). These psychological aspects of having a small business are especially relevant today since policy makers and scholars have increasingly come to focus on subjective well-being as a measure of quality of life (OECD 2011; Helliwell et al. 2016). In line with this, Wiklund et al. (2019) recently proposed that increased attention should be given to the multi-faceted nature of subjective well-being as well as relating it to small-business development, which includes starting, growing, and running a business.

The aim of this study is to increase existing knowledge of the relationship between business size and small-business owners’ subjective well-being by assessing the direct relationship as well as the relative importance of two potential mediators of this relationship. In a large sample of Swedish small-business owners, we therefore investigate the association between business size and subjective well-being. We specifically focus on the role of financial satisfaction and time pressure as potential mediators of the relationship between business size and subjective well-being. Moreover, since recent studies (Knabe et al. 2010; Kahneman and Deaton 2010) have shown important differences between two components of subjective well-being, life satisfaction, i.e. cognitive judgments of life as a whole, and emotional well-being, i.e. the emotions experienced in everyday life, we include both in the analysis. Very few studies have examined both components of subjective well-being among small-business owners and, more importantly, no studies have systematically analysed the relationship between business size and subjective well-being as well as potential mediators in this relationship. This lack of studies is surprising given that business size is often perceived to be a key indicator of a successful small-business ownership.

Our contribution is twofold. First, we provide a systematic study of the association between business size and small-business owners’ subjective well-being incorporating potential mediators in this relationship. Second, we contribute to the broader field of subjective well-being research by examining potential differences between life satisfaction and emotional well-being, the two main dependent variables in research on subjective well-being (Diener 1984; Kahneman 2011).

1.1 Small-Business Ownership and Subjective Well-Being

A large number of studies has shown that small-business owners express higher levels of job satisfaction and subjective well-being than wage earners (e.g. Blanchflower 2004; Benz and Frey 2008). Recent studies have shown that the difference is especially pronounced when comparing “opportunity-entrepreneurs” with wage earners (Coad and Binder 2014; Larsson and Thulin 2019). Although the specific mechanisms accounting for the positive relationship between small-business ownership and subjective well-being is not clear, studies suggest that a high work autonomy among small-business owners may be an important mediator (Benz and Frey 2008). Furthermore, engagement in entrepreneurial tasks has been showed to fulfil basic psychological needs such as autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Shir et al. 2019).

While it is an established fact that small-business owners generally have higher levels of subjective well-being than wage earners (Blanchflower 2004; Johansson Sevä et al. 2016; Lange 2012), we argue that the net benefit for subjective well-being of owning a larger business compared to a smaller business is less obvious. In general, we expect that the net effect of business size on subjective well-being may be relatively weak given that advantages (financial satisfaction) and disadvantages (time pressure) of a large business may cancel each other out. However, when distinguishing between the two components of subjective well-being, we expect that the association between business size and life satisfaction is positive, whereas the association between business size and emotional well-being is negative. We argue that these differences between life satisfaction and emotional well-being in relation to business size can be explained by the different nature of life satisfaction judgements compared to experiences of emotional well-being. While individuals attend to their general life circumstances when judging their life satisfaction, they relatively seldom do this when they are occupied by their daily activities (Kahneman et al. 2010). For instance, when financially successful small-business owners reflect over their life, they will most likely be satisfied, but financial success will probably be of less importance in their daily business activities. Instead, their attention may be preoccupied by engagement in demanding work tasks, which may increase feelings of stress and tension, thereby reducing emotional well-being.

We conjecture based on this reasoning that financial satisfaction should display a stronger association with life satisfaction compared to emotional well-being, since people tend to think about their material circumstances when evaluating their life but seldom attend to these circumstances in their everyday life (Kahneman et al. 2006). Conversely, time pressure should display a stronger association with emotional well-being, while a weaker association with life satisfaction, since time pressure evokes peoples’ attention constantly in their everyday life but are rarely input to judgements of life satisfaction (Kahneman and Krueger 2006). Hence, there is reason to expect that business size may affect the two components of subjective well-being differently given that financial satisfaction and time pressure are differently associated with life satisfaction and emotional well-being.

1.2 Psychological Advantages and Disadvantages Associated with Small-Business Size

The most obvious advantage of business growth for subjective well-being is that it most likely increases profits, which in turn increases small-business owners’ income and subsequent financial satisfaction. Financial satisfaction can be defined as a cognitive evaluation of one’s present financial situation (cf. Joo and Grable 2004). In previous studies, financial satisfaction is often considered to be a mediator between objective aspects of an individual’s financial situation (e.g. income or wealth) and subjective well-being (Vera-Toscano et al. 2006).

Previous studies show that both actual income and perceived change in income are associated with financial satisfaction (Davis and Helmick 1985; Sumarwan and Hira 1993). Although business growth may not increase profits per se, larger businesses have on average higher profits than smaller businesses (Cowling 2004). This suggests that business growth is one important way in which small-business owners can increase their financial satisfaction and in turn their subjective well-being. Previous research has shown that both income (Sacks et al. 2012), wealth (Halbmeier and Grabka 2019), and self-reported financial satisfaction (Johnson and Krueger, 2006) are consistently related to higher levels of subjective well-being. Although most previous studies only report cross-sectional associations between income and measures of subjective well-being, a recent study of Swedish lottery winners provides evidence that wealth has a casual effect on both financial satisfaction and life satisfaction (Lindqvist et al. 2018). Yet, no previous studies appear to have analysed the relationship between business size and financial satisfaction. Hence, the first hypothesis we investigate is:

Hypothesis 1

Business size is positively related to small-business owners’ financial satisfaction.

Increased business size may, however, also be associated with negative outcomes, which affect subjective well-being. Regarding small-business ownership in general, previous studies have found that small-business owners work longer hours compared to wage-earning employees (Parasuraman and Simmers 2001), experience work-family conflict more often (Johansson Sevä and Öun 2015), and experience higher demands in their daily work (Nordenmark et al. 2012). These potential disadvantages associated with owning small businesses are likely to increase as the business grows larger. Although no studies have explicitly examined the relationship between business size and subjective well-being, Warr (2018) investigated differences in job satisfaction between small-business owners with and without employees. The results showed that self-employed with employees experienced less job satisfaction than self-employed without employees. Warr offered possible explanations for this finding, such as longer working time, multiple management demand, and greater work overload among small-business owners with employees. Furthermore, a study relating business size to employee well-being provides indirect evidence of potential disadvantages for small-business owners related to business growth. When studying the relationship between business size, working conditions, and depression among employees, Encrenaz et al. (2018) found that employees working in larger businesses encountered higher levels of demands compared to employees working in smaller businesses. The results also showed that employees working in micro-enterprises (2-9 employees) had fewer symptoms of anxiety and depression compared to employees working in larger enterprises. As a key negative consequence of the increased demands and workload associated with larger businesses, we focus on subjective experiences of time pressure, which previous research (see the next section) has shown to be negatively associated with subjective well-being (Gärling et al. 2016). We define the subjective experience of time pressure as having too much to do in too little time (Gärling et al. 2016). In contrast to objective measures of time scarcity, which may not reduce subjective well-being per se, the feeling of time pressure has been shown to be directly related to stress-symptoms, which reduce subjective well-being (Gärling et al. 2016). Thus, our second hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 2

Business size is positively related to small-business owners’ experiences of time pressure.

1.3 The Relationship Between Business Size and Subjective Well-Being

After discussing the relationships between business size and potential advantages and disadvantages of business growth, we now turn to how these factors influence subjective well-being. Subjective well-being is commonly understood to include two major components (Diener 1984; Brülde 2007; Busseri and Sadava 2011; Tov 2018), people’s judgements of satisfaction with their life as a whole (life satisfaction) and the aggregated balance of positive and negative emotions in everyday life (emotional well-being). A similar distinction could also be made for subjective well-being at work, where global judgements of work satisfaction reflect the cognitive component and experiences of positive and negative emotions felt at work reflect the emotional component (Kahneman and Krueger 2006). Although the two components of subjective well-being show empirical overlap and have similar determinants, the strength of their relationships to financial well-being and time pressure may differ.

Several studies have shown that economic resources are more strongly associated with life satisfaction than emotional well-being. For instance, Kahneman and Deaton (2010) and Kahneman et al. (2010) reported a stronger association between income and life satisfaction than between income and emotional well-being. Kahneman et al. (2006) emphasized the role of attention in explaining such differences: people tend to attend to their financial circumstances when they make life satisfaction judgements, whereas they relatively seldom do this in their everyday life. Since previous studies indicate that economic circumstances are more important for life satisfaction than for emotional well-being (Kahneman et al. 2006; Kahneman and Deaton 2010; Lindqvist et al. 2018), business growth should primarily be expected to increase life satisfaction. We moreover expect that this relationship is mediated by financial satisfaction, which based on previous studies is an important determinant of life satisfaction (Johnson and Krueger 2006; Lindqvist et al. 2018). Hence, when small-business owners judge their life satisfaction, we anticipate that they attend to their financial well-being as one important source for their judgement. Financial well-being most likely also improve emotional well-being, but here we expect that the effect is more indirect and comparably weaker since people seldom attend to their financial situation when they are engaged in their everyday activities. This leads to our third hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3

Financial satisfaction is a stronger mediator of the relationship between business size and life satisfaction than of the relationship between business size and emotional-well-being.

In contrast to judgements of life and job satisfaction, Kahneman and Krueger (2006) showed that emotional well-being is to a larger extent correlated with attention-evoking factors in the immediate environment. For instance, when analysing the relationship between job circumstances, job satisfaction and emotional well-being at work, they found that time pressure (“a constant pressure to work fast”) and high demands (“a constant attention to avoid mistakes”) correlated more strongly with emotional well-being at work than with job satisfaction. Kahneman et al. (2010) and Knabe et al. (2010) also noted that time use seems to be a more important determinant of emotional well-being compared to life satisfaction. For instance, unemployed people report vastly lower life satisfaction than employed people despite the fact that their duration-weighted emotional well-being is not worse (Knabe et al. 2010). According to Knabe et al. (2010), unemployed individuals compensate their lack of employment by having more time to spend on pleasant activities. Moreover, unemployed individuals may experience lower levels of time pressure in their daily lives compared to individuals working, which could also explain why unemployment is less detrimental for individuals’ emotional well-being than their life satisfaction.

In two recent surveys of Swedish employees, time pressure reduced positive emotions and amplified negative emotions such that it resulted in a negative impact on emotional well-being (Gärling et al. 2016). These studies also showed that the negative effect of time pressure was jointly mediated by impediment to goal progress (both at work and off work) and the prevalence of stress symptoms. However, these studies did not investigate small-business owners, neither did they directly compare how the two components of subjective well-being relate to business size as well as the advantages and disadvantages of owning a larger business.

The positive consequences of owning a larger business on emotional well-being are expected to be offset by time pressure, which reduces emotional well-being. Hence, we expect that working under time pressure is stressful for small-business owners such that it will reduce their everyday emotional well-being, whereas their life satisfaction judgements are more dependent of their financial satisfaction. It therefore follows that the association between time pressure and emotional well-being should be stronger than the association between time pressure and life satisfaction. Hence, we propose the fourth hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4

Time pressure is a stronger mediator of the relationship between business size and emotional well-being than of the relationship between business size and life satisfaction.

2 Method

2.1 Sample and Procedure

The sample was provided by the Swedish Federation of Business Owners who recruited participants from their internet panel consisting of 3715 small-business owners in Sweden. No ethical approval was required in line with the local regulations since we did not handle any personal information (all data were anonymized). An invitation e-mail sent to all panel members resulted in a sample of 1208 participants representing a response rate of 32%. The demographic profile of the sample is presented in “Appendix”. The participants completed an online questionnaire consisting of 109 items. We retained 1089 participants who answered all questions used in the data analyses.

2.2 Questionnaire and Measures

The survey covered questions about the small-business performance, the work environment, and leisure. In this study, we only analyse the survey questions described below about business size, time pressure, financial satisfaction, emotional well-being, and life satisfaction. In the results section we report reliability and construct, discriminant and convergent validity of the latent measures of subjective well-being, financial satisfaction and time pressure.

To measure business size, we used self-reported revenues. Participants reported the annual revenue of their company in SEK (1 SEK approximately equal to 0.10 Euro and 0.125 USD at the time of the study) by selecting one of the following nine categories: “0–99,999”, “100,000–499,999”, “500,000–999,999”, “1000,000–1999,999”, “2000.000–4999,999”, “5000,000–9999,999”, “10,000,000–49,999,999”, “50,000,000–99,999,999” and “100,000,000 or higher”. The distribution for this variable is reported in the “Appendix”. An alternative measure of business size is the number of employees (which we also measured with 7 categories in the survey). A robustness test using this measure (r = .80 with self-reported revenues) did not yield different results.

In previous studies, financial satisfaction is often measured using single items (cf. Joo and Grable 2004). In the present study we used two items. Participants indicated their satisfaction with their “private financial situation” on a 7-point bipolar scale ranging from 0 (“extremely dissatisfied”) to 6 (“extremely satisfied”). Participants also reported their satisfaction with the “profitability” of their business using the same scale as above. In order to reduce measurement errors we used both indicators to estimate a latent factor.

We obtained the measure of time pressure at work by adapting the overall self-report measure of time pressure used in Gärling et al. (2016), which is the only existing multi-item measure of the subjective experience of time pressure. The measure of time pressure at work was obtained from agreement ratings on 7-point scales of the statements: “I frequently feel that I don’t have enough time to complete my job assignments”, “At my job, I frequently feel I need to hurry to be in time”, and “I frequently feel rushed due to insufficient time at work”.

Life satisfaction was assessed with the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS) which is frequently used to measure life satisfaction (Diener et al. 1985; Pavot and Diener 2008). The scale consists of five statements (e.g., “In most ways, my life is close to my ideal”). Agreement to these statements were rated on a scale from 0 (“Do not agree at all”) to 6 (“Completely agree”).

Finally, in order to assess emotional well-being, retrospective ratings were collected of the frequency of emotions felt during the last month at work and off work, respectively. We used four unipolar adjective scales with seven steps ranging from “never” (0) to “always” (6). Participants indicated how often during the past month they felt positive emotions (glad, pleased, happy) and negative emotions (sad, displeased, depressed). The adjectives defining the scales were adopted from the Swedish Core Affect Scale (SCAS) (Västfjäll et al. 2002; Västfjäll and Gärling 2007). The items used in the analysis (translated from Swedish) are presented in Table 1.

3 Results

We used covariance-based structural equation modeling (SEM) with maximum-likelihood estimation (M + 7.12) to analyze the relationships between the measures of business size, financial satisfaction, time pressure, life satisfaction, and emotional well-being.

We first estimated a measurement model for an acceptable model fit (RMSEA = 0.075; CFI = 0.950; SRMR = 0.038) including the latent factors corresponding to the hypothesized mediators (financial satisfaction and time pressure) and dependent variables (life satisfaction and emotional well-being). The chi-square value of 500.25 was significant (p < 0.001), which is to be expected for a large sample (n = 1089). Table 1 reports means, standard deviations, skewness, kurtosis, and factor weights for the indicators. As can be seen, weights range from .68 to .89 and are all significant (p < 0.001). Product moment correlations between the indicators are also reported. Following guidelines proposed by Hair et al. (2009), construct, discriminant and convergent validity were assessed. Table 2 reports the correlations between the latent factors, composite reliability (CR), Cronbach’s alpha (α), average variance extracted (AVE), maximum shared squared variance (MSV), and average shared squared variance (ASV). The Cronbach’s alphas and composite reliabilities exceed an acceptable value of 0.70. Further, since AVE is larger than 0.50 and CR larger than AVE, the threshold for convergent validity is reached. Discriminant validity is satisfactory since AVE is larger than both MSV and ASV.

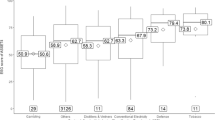

We proceeded by fitting the structural model in Fig. 1 to test the hypotheses regarding the relationship between business size and subjective well-being. In fitting the structural model, we included financial satisfaction and time pressure as mediators of the relationship between business size and both components of subjective well-being. The indirect effects of business size on life satisfaction correspond to a one-path mediation through financial satisfaction (business size → financial satisfaction → life satisfaction) and a one-path mediation through time pressure (business size → time pressure → life satisfaction). Similarly, the indirect effects of business size on emotional well-being correspond to a one-path mediation through financial well-being (business size → financial satisfaction → emotional well-being) and a one-path mediation effect through time pressure (business size → time pressure → emotional well-being). Since there may be other potential mediators of the relationship between business size and subjective well-being, we also included a direct effect from business size to each component of subjective well-being. As the relationship between life satisfaction and emotional well-being is generally observed to be positive bidirectional (Busseri and Sadava 2011), we included a correlation between these two latent factors. Finally, we also included a correlation between time pressure and financial satisfaction since previous research suggests that time pressure may influence progress towards work-related goals (Gärling et al. 2016).

According to Hypothesis 1, business size should have a direct effect on financial satisfaction, whereas according to Hypothesis 2, business size should have a direct effect on time pressure. Hypothesis 3 proposes that financial satisfaction is a stronger mediator of the relationship between business size and life satisfaction compared to the relationship between business size and emotional well-being. Conversely, Hypothesis 4 states that time pressure is a stronger mediator of the relationship between business size and emotional well-being compared to the relationship between business size and life satisfaction. Hence, we expect that financial satisfaction and time pressure mediates the relationship between business size and both components of subjective well-being but that their relative strength as mediators differs.

Standardized regression coefficients are presented in Fig. 1 along with more detailed information of these estimates in Table 3. In the following, please note that we use the term “effect” only in a technical sense since we analyze cross-sectional data. As expected, due to the large sample, the chi-square value 511.167 was significant (p < 0.001). All other fit indices were acceptable (RMSEA = .070; CFI = .951; SRMR = .036) suggesting a good fit to the data. The results in Table 2 show that business size has a non-significant total effect on life satisfaction (β = .029, p = .353) but a significant negative total effect on emotional well-being (β = -.067, p = .046). As we show below, these weak or non-significant total effects are partly obtained because advantages (financial satisfaction) and disadvantages (time pressure) associated with business size cancel each other out.

As expected, Fig. 1 shows that the correlation between life satisfaction and emotional well-being is positive and that the correlation between financial satisfaction and time pressure is negative. More importantly, the figure also shows that financial satisfaction and time pressure increase significantly with business size confirming hypotheses 1 and 2. Furthermore, these effects are similar in size and do not differ significantly since the corresponding confidence intervals overlap (see Table 3). The results thus suggest that increasing business size symmetrically results in advantages and disadvantages for small-business owners. We also find that business size has a weak negative direct effect on both life satisfaction and emotional well-being suggesting that there may be other disadvantages associated with larger businesses.

Table 3 shows that both financial satisfaction and time pressure display significant effects on both components of subjective well-being. However, financial satisfaction has significantly stronger effect on life satisfaction compared to emotional well-being whereas the opposite holds true for time pressure.

According to hypothesis 3 we expected that financial satisfaction is a stronger mediator of the relationship between business size and life satisfaction than of the relationship between business size and emotional well-being. In hypothesis 4 we further proposed that time pressure is a stronger mediator of the relationship between business size and emotional well-being than of the relationship between business size and life satisfaction. As shown in Table 3, the indirect effect of business size on life satisfaction through financial satisfaction is significant as is the indirect effect of business size on emotional well-being through financial satisfaction. Although these indirect effects are not significantly different as judged by the overlapping confidence intervals, they provide tentative support for hypothesis 3. Turning to hypothesis 4, the indirect effect of business size on life satisfaction through time pressure is significant as is the indirect effect of business size on emotional well-being through time pressure. The differences in strength of these indirect effects is statistically significant since the confidence intervals do not overlap. Hypothesis 4 is thus confirmed.

4 Discussion

In a large sample of small-business owners, we investigated the relationship between business size and subjective well-being by specifically focusing on the relative importance of advantages (financial satisfaction) and disadvantages (time pressure) related to business size. Our results show that the overall association between business size and life satisfaction is close to zero and not statistically significant, while there is a weak negative association between business size and emotional well-being. We show that these absent or weak associations can be explained by the fact that advantages and disadvantages of a larger business tend to cancel each other out. Specifically, business size is associated with financial satisfaction and time pressure to the same degree, and financial satisfaction and time pressure are related to subjective well-being in opposite directions. Hence, in our model financial satisfaction and time pressure both mediate the effect of business size on subjective well-being. While this result is our main finding, we also observe that business size has a direct negative relationship to subjective well-being.

Turning to differences between the two components of subjective well-being, we find that financial satisfaction has a stronger positive association with life satisfaction than with emotional well-being. Conversely, we find that time pressure has a stronger negative association with emotional well-being than with life satisfaction. Regarding differences between the two components of subjective well-being in relation to the mediation of time pressure and financial satisfaction, we find that time pressure is a stronger mediator of the relationship between business size and emotional well-being than of the relationship between business size and life satisfaction. Similarly, we find that the opposite mediation pattern exists in relation to financial satisfaction. However, this difference is slightly less pronounced and not statistically significant.

Our study contributes to the small-business literature by addressing the issue of whether business size is related to subjective well-being as well as positive and negative psychological consequences in the form of financial satisfaction and time pressure. We interpret our findings in the following way. While large businesses tend to make small-business owners more satisfied with their financial situation which in turn raises their subjective well-being, it simultaneously imposes more strain on small-business owners due to increasing time pressure, which reduces their subjective well-being. In fact, our study shows that business growth may even be detrimental for small-business owners’ emotional well-being. This suggests that the multi-component nature of subjective well-being need to be taken into consideration when assessing advantages and disadvantages associated with firm growth. While previous studies have shown that small-businesses owners have higher levels of subjective well-being than wage earners, we show that business growth does not necessarily increase subjective well-being, highlighting the need to further study the dynamics of small-business ownership in relation the multi-faceted nature of subjective well-being (cf. Wiklund et al. 2019).

The differences in results for life satisfaction and emotional well-being raise questions about which component of subjective well-being to improve in the small-business community. If raising small-business owner’s life satisfaction, a focus on their financial well-being would be a higher priority than reducing their time pressure. If, on the other hand, small-business owners emotional experience is what ultimately matters most, one would be equally interested in reducing their time pressure. Although we do not claim to have answers to such normative questions, our study may increase awareness of the need to distinguish between the cognitive and emotional components of subjective well-being when discussing small-business owners’ well-being and how to promote it.

This study also contributes to the wider literature on subjective well-being by demonstrating differences in the relative strengths of the determinants of cognitive and emotional aspects of subjective well-being. Life satisfaction and emotional well-being have been studied as separate constructs since they are not perfectly correlated and may have different determinants (Diener and Tov 2012; Kahneman and Deaton 2010). Our study confirms the need of doing this. Specifically, our results are in line with Kahneman and Krueger (2006) who found that time pressure has a stronger association with emotional well-being at work than with job satisfaction, as well as with studies showing that income is more strongly associated with life satisfaction than with emotional well-being (Kahneman et al. 2006; Kahneman and Deaton 2010). Our results are also in line with a recent longitudinal study that found much stronger effects of wealth on measures of financial satisfaction and life satisfaction compared to measures of happiness and mental health (Lindqvist et al. 2018). Another contribution is that we used latent measures of both life satisfaction and emotional well-being which is an improvement over many previous studies that have compared the determinants of life satisfaction and emotional well-being (e.g. Kahneman et al. 2006; Kahneman and Deaton 2010; Knabe et al. 2010). Single-item indicators or manifest multi-item indicators may have limitations when it comes to the reliability of the measures. Observed differences between life satisfaction and emotional well-being could then be spurious due to measurement errors.

Based on our findings we identify several additional important questions for future research. First, the relationship between business size, time pressure, financial satisfaction, and subjective well-being should be studied using research designs that are better suited to make casual inferences. Ideally, controlled experiments should be used to isolate cause and effect. However, since such experiments are complicated or impossible to set up, longitudinal research designs may be a more realistic option. By following the same panel of individuals over time, one could assess if changes in business size are accompanied by changes in time pressure, financial satisfaction, and subjective well-being.

Since our study show that financial satisfaction and time pressure only partially mediate the effect of business size on both components of subjective well-being, future studies should therefore try to identify and investigate additional mediators of this relationship. Two such potential mediators could be experiences of work-family conflict and dissatisfaction with leisure time, which reduce subjective well-being (Matthews et al. 2014; Newman et al. 2014) and may increase with business growth.

Another avenue for future research is to investigate if the negative relationship between business size and time pressure is linear or if thresholds exist that results in a weak or even negative relationship. For example, at some point as the business size increases, the owner may have the opportunity to hire assistants to decrease the work-load. Under such circumstances, having a larger business may not increase time pressure as much.

A further question for future studies is to investigate potential moderators of the relationships between business size, time pressure, financial satisfaction, and subjective well-being. For instance, business growth may not increase time pressure for all individuals, but only for individuals who lack adequate coping techniques (Hutchinson and Williams 2007), or for individuals that score high on certain personality traits such as neuroticism (Fors Connolly et al. 2020).

In our study, the measure of time pressure is an indicator of workload (or job demands). Work load may be assessed more broadly by items included in the Job Content Questionnaire (Karasek et al. 1988). However, since items tapping into time pressure routinely are used as indicators for high job demands and workload, it is unlikely that our results would have been different using other measures of workload. Still, future research should attempt to replicate our findings by using broader measures of workload.

Finally, we acknowledge some additional limitations. Since our analysis was based on cross-sectional data, casual interpretations of the observed associations need to be made with caution. As already noted, future studies should attempt to assess the relationships between business size, time pressure, financial satisfaction, and subjective well-being using longitudinal research designs. We also want to stress that our sample consisted of small-business owners in Sweden. Hence, we cannot be certain that the results would hold in other institutional and cultural contexts. For instance, the relationship between financial satisfaction and subjective well-being among small-business owners may be stronger in other countries since the Swedish culture emphasizes relatively non-materialistic values compared to other cultures (Delhey 2010). Another limitation is our use of retrospective questions to measure emotional well-being, which may be less valid than momentarily assessed emotional well-being collected by means of experience sampling (Larson and Csikszentmihalyi 1983). Still, previous research demonstrates that people are fairly accurate in assessing their general mood in retrospect (Wirtz et al. 2003; Hudson et al. 2020).

Regarding policy implications, our results confirm the importance of considering both financial satisfaction and time pressure when discussing potential advantages and disadvantages of firm growth and business expansion. We believe that the tendency to overlook negative consequences of business growth in terms of time pressure may have negative consequences not only for business owners themselves but also for society as a whole. If policy makers not only want to stimulate people to start new businesses but also want to stimulate growth among existing small businesses, they need to acknowledge the high emotional costs many small-business owners may pay due to increasing workload as the company grows larger. If not, the disadvantages associated with business growth may hinder the development of larger businesses in society, which in turn can have negative consequences for economic growth and job creation.

References

Benz, M., & Frey, B. S. (2008). The value of doing what you like: Evidence from the self-employed in 23 countries. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 68(3–4), 445–455.

Blanchflower, D. G. (2004). Self-employment: More may not be better. Swedish Economic Policy Review, 11(2), 15–73.

Braidford, P., Drummond, I., & Stone, I. (2017). The impact of personal attitudes on the growth ambitions of small business owners. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 24(4), 850–862.

Brülde, B. (2007). Happiness and the good life. Introduction and conceptual framework. Journal of Happiness Studies, 8(1), 1–14.

Busseri, M. A., & Sadava, S. W. (2011). A review of the tripartite structure of subjective well-being: Implications for conceptualization, operationalization, analysis, and synthesis. Personality and social psychology review, 15(3), 290–314.

Cassar, G. (2007). Money, money, money? A longitudinal investigation of entrepreneur career reasons, growth preferences and achieved growth. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 19(1), 89–107.

Coad, A., & Binder, M. (2014). Causal linkages between work and life satisfaction and their determinants in a structural VAR approach. Economics Letters, 124(2), 263–268.

Cowling, M. (2004). The growth–profit nexus. Small Business Economics, 22(1), 1–9.

Davidsson, P. (1989). Entrepreneurship—and after? A study of growth willingness in small firms. Journal of Business Venturing, 4(3), 211–226.

Davidsson, P. (1991). Continued entrepreneurship: Ability, need, and opportunity as determinants of small firm growth. Journal of Business Venturing, 6(6), 405–429.

Davidsson, P. (2004). Researching entrepreneurship. New York: Springer.

Davis, E. P., & Helmick, S. A. (1985). Family financial satisfaction: The impact of reference points. Home Economics Research Journal, 14(1), 123–131.

Delhey, J. (2010). From materialist to post-materialist happiness? National affluence and determinants of life satisfaction in cross-national perspective. Social Indicators Research, 97(1), 65–84.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542.

Diener, E., & Tov, W. (2012). National accounts of well-being. In K. C. Land, A. C. Michalos, & M. J. Sirgy (Eds.), Handbook of social indicators and quality of life research (pp. 137–158). New York: Springer.

Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75.

Encrenaz, G., Laberon, S., Lagabrielle, C., Debruyne, G., Pouyaud, J., & Rascle, N. (2018). Psychosocial risks in small enterprises: The mediating role of perceived working conditions in the relationship between enterprise size and workers’ anxious or depressive episodes. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, 1–10, 485.

Fors Connolly, F., Johansson Sevä, I., & Gärling, T. (2020). How does time pressure influence emotional well-being? Investigating the mediating roles of domain satisfaction and neuroticism among small-business owners. International Journal of Well-Being, 10(2), 19–36.

Gärling, T., Gamble, A., Fors, F., & Hjerm, M. (2016). Emotional well-being related to time pressure, impediment to goal progress, and stress-related symptoms. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(5), 1789–1799.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2009). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). New York: Pearson Prent.

Halbmeier, C., & Grabka, M. M. (2019). Wealth changes and their impact on subjective well-being. In G. Brulé & C. Suter (Eds.), Wealth (s) and subjective well-being (pp. 401–414). Berlin: Springer.

Helliwell, J. F., Layard, R., & Sachs, J. (2016). World Happiness Report 2016 Update. New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network: A Global Initiative for the United Nations.

Henrekson, M., & Stenkula, M. (2009). Entrepreneurship and public policy. Stockholm: Research Institute of Industrial Economics.

Hudson, N. W., Anusic, I., Lucas, R. E., & Donnellan, M. B. (2020). Comparing the reliability and validity of global self-report measures of subjective well-being with experiential day reconstruction measures. Assessment, 27(1), 102–116.

Hutchinson, J. G., & Williams, P. G. (2007). Neuroticism, daily hassles, and depressive symptoms: An examination of moderating and mediating effects. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(7), 1367–1378.

Johansson Sevä, I., & Öun, I. (2015). Self-employment as a strategy for dealing with the competing demands of work and family? The importance of family/lifestyle motives. Gender, Work & Organization, 22(3), 256–272.

Johansson Sevä, I., Vinberg, S., Nordenmark, M., & Strandh, M. (2016). Subjective well-being among the self-employed in Europe: macroeconomy, gender and immigrant status. Small Business Economics, 46(2), 239–253.

Johnson, W., & Krueger, R. F. (2006). How money buys happiness: genetic and environmental processes linking finances and life satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(4), 680–691.

Joo, S. H., & Grable, J. E. (2004). An exploratory framework of the determinants of financial satisfaction. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 25(1), 25–50.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Macmillan.

Kahneman, D., & Deaton, A. (2010). High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(38), 16489–16493.

Kahneman, D., & Krueger, A. B. (2006). Developments in the measurement of subjective well-being. Journal of Economic perspectives, 20(1), 3–24.

Kahneman, D., Krueger, A. B., Schkade, D., Schwarz, N., & Stone, A. A. (2006). Would you be happier if you were richer? A focusing illusion. Science, 312(5782), 1908–1910.

Kahneman, D., Schkade, D. A., Fischler, C., Krueger, A. B., & Krilla, A. (2010). The structure of well-being in two cities: Life satisfaction and experienced happiness in Columbus, Ohio; and Rennes, France. In E. Diener, J. F. Helliwell, & D. Kahneman (Eds.), International differences in well-being (pp. 16–33). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Karasek, R., Brisson, C., Kawakami, N., Houtman, I., Bongers, P., & Amick, B. (1988). The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): An instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 3(4), 322–355.

Knabe, A., Rätzel, S., Schöb, R., & Weimann, J. (2010). Dissatisfied with life but having a good day: time-use and well-being of the unemployed. The Economic Journal, 120(547), 867–889.

Larson, R., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1983). The experience sampling method. New Directions for Methodology of Social & Behavioral Science, 15, 41–56.

Larsson, J. P., & Thulin, P. (2019). Independent by necessity? The life satisfaction of necessity and opportunity entrepreneurs in 70 countries. Small Business Economics, 53(4), 921–934.

Lindqvist, E., Oestling, R., & Cesarini, D. (2018). Long-run Effects of lottery wealth on psychological wellbeing. NBER Working Paper, 24667.

Matthews, R. A., Wayne, J. H., & Ford, M. T. (2014). A work–family conflict/subjective well-being process model: A test of competing theories of longitudinal effects. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(6), 1173–1187.

Morrison, A., Breen, J., & Ali, S. (2003). Small business growth: intention, ability, and opportunity. Journal of Small Business Management, 41(4), 417–425.

Newman, D. B., Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2014). Leisure and subjective well-being: A model of psychological mechanisms as mediating factors. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(3), 555–578.

Nordenmark, M., Vinberg, S., & Strandh, M. (2012). Job control and demands, work-life balance and wellbeing among self-employed men and women in Europe. Vulnerable Groups & Inclusion, 3(1), 188–196.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2011). How’s life? Measuring well-being. Paris: OECD.

Parasuraman, S., & Simmers, C. A. (2001). Type of employment, work–family conflict and well-being: A comparative study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(5), 551–568.

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(2), 137–152.

Sacks, D. W., Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2012). The new stylized facts about income and subjective well-being. Emotion, 12(6), 1181–1187.

Shir, N., Nikolaev, B. N., & Wincent, J. (2019). Entrepreneurship and well-being: The role of psychological autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(5), 105875.

Sumarwan, U., & Hira, T. K. (1993). The effects of perceived locus of control and perceived income adequacy on satisfaction with financial status of rural households. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 14(4), 343–364.

Thomas, L. (2012). Job satisfaction and self-employment: Autonomy or personality? Small Business Economics, 38(2), 165–177.

Tov, W. (2018). Well-being concepts and components. In E. Diener, S. Oishi, & L. Tay (Eds.), Handbook of well-being. Salt Lake City, UT: DEF Publishers.

Västfjäll, D., & Gärling, T. (2007). Validation of a Swedish short self-report measure of core affect. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 48, 233–238.

Västfjäll, D., Friman, M., Gärling, T., & Kleiner, M. (2002). The measurement of core affect: A Swedish self-report measure derived from the affect circumplex. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 43, 19–31.

Vera-Toscano, E., Ateca-Amestoy, V., & Serrano-Del-Rosal, R. (2006). Building financial satisfaction. Social Indicators Research, 77(2), 211–243.

Warr, P. (2018). Self-employment, personal values, and varieties of happiness–unhappiness. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(3), 388–401.

Wiklund, J., Nikolaev, B., Shir, N., Foo, M. D., & Bradley, S. (2019). Entrepreneurship and well-being: Past, present, and future. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(4), 579–588.

Wirtz, D., Kruger, J., Scollon, C. N., & Diener, E. (2003). What to do on spring break? The role of predicted, on-line, and remembered experience in future choice. Psychological Science, 14(5), 520–552.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Umea University. The data collection was funded by The Swedish Federation of Business Owners. We thank René Bongard who conducted the data collection. We also thank two reviewers and the editor for their valuable comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The author declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fors Connolly, F., Johansson Sevä, I. & Gärling, T. The Bigger the Better? Business Size and Small-Business Owners’ Subjective Well-Being. J Happiness Stud 22, 1071–1088 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00264-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00264-2