Abstract

Study engagement has been considered a key predictor of school performance among students. Although the potential contribution of positive psychology to education has been recognised, the research findings and implications related to primary school students remain largely unexplored. Given that authentic happiness theory and the broaden-and-build theory have posited the important roles of positive emotions, meaning, engagement and strengths use in education, a more comprehensive study is needed to understand their interactions across time. The current longitudinal study examined the interrelationships between these positive attributes among Chinese students in Hong Kong, China. A total of 786 primary school students from Grades 4 to 6 completed the questionnaire survey at two time points one year apart. An autoregressive cross-lagged panel (ARCL) with structural equation modelling was applied for the data analysis. The results revealed that positive emotions predicted positive meaning, strengths use and study engagement across time. Positive emotions and meaning were reciprocally correlated with each other. Moreover, the use of strengths mediated the association between positive emotions and study engagement. The implications and future directions are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The increasing interest in engagement reflects a general emerging trend towards positive psychology, which focuses on human strengths and optimal functioning rather than on weaknesses and malfunctioning (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi 2000). Although many definitions have been applied to the construct of study engagement, here we define it as a positive, fulfilling and study-related state of mind characterised by vigour, dedication and absorption (Schaufeli et al. 2002) that refers to a more persistent and pervasive affective-cognitive state rather than a momentary and specific state (Schaufeli and Bakker 2004). Study engagement has attracted increased focus from educators, investigators and policymakers in recent decades because it is considered a key solution to problems in schools (e.g., discipline, low academic achievement and high dropout rates) (Fredricks et al. 2004) and a predictor of school performance (Salanova et al. 2010a). In addition, research indicated that students with high study engagement are less likely to suffer from burnout (Schaufeli et al. 2002), anxiety and depressive symptoms (Li and Lerner 2011) and more likely to experience personal growth (Upadyaya and Salmela-Aro 2013) and well-being (Lewis et al. 2011). In sum, study engagement can be linked to students’ overall success and is of fundamental importance for understanding positive youth development (Schaufeli and Bakker 2004).

Theories of study engagement postulate complex interactions between individuals and their contexts. Among them, some researchers are more interested in person-situation interactions, assuming that study engagement is responsive to contextual features and various environmental factors, including teacher support, relationships with parents and peers, and school climate (e.g., Kadha 2009; Lee 1996; Fredricks et al. 2004). Some focus more on the person-related factors (i.e., intrapersonal characteristics) such as personality traits and positive attributes. In the current study, situated within a positive psychology perspective, we adopted the intrapersonal approach and explored individual factors affecting study engagement based on the authentic happiness framework. Authentic happiness theory, combining the hedonic and eudemonic approaches, posits three pathways to well-being: pleasure, meaning and engagement (Schueller and Seligman 2010; Seligman 2002). It is grounded in three traditional theories: hedonism theory (pleasure), desire theory (engagement) and objective list theory (meaning) (Seligman and Royzman 2003), which are examined in this study via positive emotions, study engagement and positive meaning, respectively. Experiencing positive emotions, obtaining meaning and pursuing engagement are intertwined with one another, and the presence of all three is considered to provide access to ‘the full life’ (Seligman 2002, 2012).

In this article, we adopt a more generic conceptualisation of human strengths as ‘a pre-existing capacity for a particular way of behaving, thinking, or feeling that is authentic and energising to the user. It enables optical functioning, development and performance’ (Linley 2008). The identification and deployment of strengths are the foundation of well-being, and are correlated with the three positive attributes: positive emotions, meaning and engagement (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi 2000). Although theoretical perspectives in positive psychology emphasise that both possessing and using strengths are equally important, existing research has focused exclusively on having rather than using strengths (Wood et al. 2011). Therefore, there is limited research on the use of strengths, especially among students. The present study aims to fill this gap (Proctor et al. 2011).

In sum, although initial research supports the tenets of ‘a flourishing life’ (Schueller and Seligman 2010), few studies have investigated this theory comprehensively, integrating all three positive attributes and the use of strengths simultaneously, particularly with children in the school context across time. As study engagement has been demonstrated as an essential protective factor to promote positive educational and social outcomes for students (O’Farrell and Morrison 2003), the current study used a longitudinal design to explore the roles of positive emotions, meaning and use of strengths in contributing to study engagement among primary school students. This is an important step forward in identifying the potential underlying processes of strengths deployment that links these positive attributes together.

1.1 Positive Emotions and Study Engagement

The broaden-and-build theory suggests that positive emotions are essential elements of optimal functioning (Fredrickson 2001, 1998). It is proposed that distinct positive emotions (e.g., joy, love, interest and contentment) share the capacity to ‘broaden’ momentary thought–action repertoires (Fredrickson and Branigan 2005). These exploratory characteristics (e.g., flexibility and creativity) create learning opportunities to integrate diverse materials which subsequently help students ‘build’ their personal enduring resources (i.e., physical, intellectual, social and psychological resources). Accordingly, an adaptive ability is produced to manage future challenges (e.g., Fredrickson 2003). The cumulative effects of ‘building through broadening’ may guide thoughts and behaviour in the long run so as to enhance students’ study engagement and improve their prospective health and overall well-being (Fredrickson and Branigan 2005; Kwok et al. 2015).

The effect of positive emotions on study engagement can be explained by the fact that positive affect facilitates approach behaviour, which prompts students to be engaged in particular activities (e.g., Cacioppo et al. 1999). The experience of positive emotions has been found to be positively associated with increased study engagement in both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (Reschly et al. 2008). Nevertheless, it seems somewhat simplistic and restrictive to propose an exclusively one-directional relationship and not consider reverse causation and reciprocal effects in these dynamic processes (Salanova et al. 2010b). As an empirical study has demonstrated a reciprocal relationship between positive emotion and engagement among Western university students and secondary school teachers (Ouweneel et al. 2011; Salanova et al. 2011), it is reasonable to posit such a reciprocal relationship among young students in Eastern countries.

H1a

Positive emotions (PE) at T1 would be positively correlated with study engagement (SE) at T2

H1b

SE at T1 would be positively correlated with PE at T2

1.2 Positive Meaning and Study Engagement

Positive meaning among students is defined as the value, purpose and significance of study judged in relation to a student’s own ideals or standards (Csikszentmihalyi 2014). While finding meaning in study is perhaps the most difficult dimension to apply in schools, it is possibly the most crucial. Significantly higher levels of study engagement have been found when learning is perceived as interesting, challenging and meaningful (Shernoff et al. 2003). Meaningful activities can be the key to fostering students’ intrinsic motivation, concentration and attentiveness (May et al. 2004). In other words, when students feel that study is meaningful, they are more likely to engage. However, other researchers have found meaning to be a consequence of engagement (Mendes and Stander 2011). That is, when students are engaged, they are more aware of the significance and values of the activity. Consequently, they may assign positive meaning to the tasks when time and effort are spent in study. Taken together, the linkages between positive meaning and study engagement are likely due not only to the effects of meaning, but also to the effects of engagement, implying reciprocal rather than unidirectional causation.

H2a

Positive meaning (PM) at T1 would be positively correlated with study engagement (SE) at T2;

H2b

SE at T1 would be positively correlated with PM at T2.

1.3 Positive Emotions and Positive Meaning

Positive emotions, on its own may not be sufficient for study engagement. It may be that having positive affect facilitates students with other positive attributes to engage with study (Steger et al. 2013). Fredrickson (2005) argues that positive meaning is a possible factor that interacts with positive emotions. On the one hand, positive emotions, rather than just fleeting affective states, enable individuals to create and pursue abstract and long-term goals by increasing their sensitivity to the meaning relevance of a situation (King et al. 2006; Kwok and Gu 2017). Students may find positive meaning within school life when they experience positive emotions. On the other hand, finding positive meaning in study-related activities is likely to produce more experiences of interest, joy and love (Fredrickson 2000). Although Fredrickson (2005) emphasised that in theory, positive meaning and emotions go hand in hand, to date, only one empirical study has supported the impact of positive emotions on meaning of life among adults in America (King et al. 2006). This reciprocal relation has yet to be examined and supported, especially in the educational context.

H3a

Positive emotions (PE) at T1 would be positively correlated with positive meaning (PM) at T2

H3b

PM at T1 would be positively correlated with PE at T2.

1.4 Use of Strengths as a Mediator

A key aspect of the research agenda of the positive psychology approach focuses on personal strengths, the use of which is energising and allows students to achieve more and work towards fulfilling their potential (Linley and Harrington 2006), in turn leading to positive experiences (Linkins et al. 2015). In other words, strengths are the characteristics that allow a person to perform well or at their personal best. In this study, individuals interpret the meaning of strengths for themselves rather than having a restrictive definition imposed on them.

It has been suggested that essential drivers of engagement are identifying and then applying one’s strengths, along with managing emotions and finding meaning (Crabb 2011). A more recent study demonstrated that the experience of positive emotions predicted students’ future personal resources, which subsequently predicted study engagement (Ouweneel et al. 2011). Based on the broaden-and-build theory, strengths use can be considered one of the personal resources people have that mediates the relationship between positive emotions and study engagement. It may also play an important role in the relationship between finding meaning and study engagement (Ouweneel et al. 2011). Specifically, students having positive emotions and positive meaning tend to participate in learning activities that are congruent with their strengths and align with the corresponding emotions and meaning, so that the use of strengths may promote study engagement (Park and Peterson 2007). Collectively, it seems plausible that strengths use, as a personal resource, may mediate the processes by which positive emotions and meaning influence study engagement among students (Weber et al. 2016). However, this mediating role of strengths use is relatively unexplored. Evaluating its role and underlying mechanism could provide more information for the conceptual understanding of the learning process and practices in positive education (Lai et al. 2018).

H4a

Strengths use (SU) would mediate the association between PE and SE; and

H4b

SU would mediate the association between PM and SE.

1.5 Unique Contribution of the Present Study

The current study investigates a comprehensive model including positive emotions (emotion), meaning (cognition), strengths use (behaviour) and study engagement (behaviour) among primary school students using a longitudinal design (theoretical framework as in Fig. 1). Despite the previous literature linking positive emotions, meaning and engagement, their interrelated reciprocal relations remain a set of theory-based hypotheses that require empirical support. Few studies have analysed all three attributes together and their interactive effects simultaneously using a longitudinal design. None of the cross-sectional studies have examined strengths use as a mediator and its underlying mechanism. Additionally, although the potential contribution of positive psychology conceptualization to school psychology have been recognised by some professionals, the findings and implications related to primary school students remain largely unexplored (Wilkins et al. 2015). As a result, the current study may fill the gaps mentioned above.

Last but not least, our study may expand the literature, which has targeted mainly Western samples, as it is yet to be ascertained whether these models can be applied to Eastern populations. Scholars have claimed that the individualistic bias of some concepts within positive psychology may not be universally applicable and transferable to collectivist cultures (Christopher and Hickinbottom 2008). Specifically, in contrast to the Western culture of individualism, the core issues in East Asian collectivist cultures are the fulfilment of social roles and obligations in interdependent relationships, and promotion of the welfare and prosperity of the collective, even at the cost of personal benefit (Lu and Gilmour 2006). Due to Confucianism, Asians advocate self-criticism and humility as virtues to create and maintain interpersonal harmony (Kitayama and Markus 2000). They are reluctant to express their feelings and too humble to show their strengths. People prefer to pursue socially desirable and culturally mandated achievements rather than to strive for personal accomplishment (Lu and Gilmour 2006). In short, East Asian cultures prioritise collective welfare over personal interests. Therefore, the understanding and motivation of ‘study’ may be very different. Thus, further investigation of the classic Western models in the Chinese educational context is another important contribution.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants and Procedure

A longitudinal survey was conducted in 2016 and 2017. The principals of two primary schools with similar backgrounds (in terms of student socioeconomic status and academic performance) were contacted and agreed to join the survey. Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the affiliated university. The surveys were self-reported in classes for about 20–30 min without the presence of teachers, but a research assistant was present to answer questions. The students were invited to participate, and formal written consent was obtained from both parents and students before the study. The consent form clearly explained the purpose of the study, and students were informed that their participation was entirely voluntary, not financially compensated and they could withdraw at any time. Their identities were collected only for the matching of data at different time points, and all information was kept strictly confidential to the research team. Only summary statistics are used in the research reports and papers.

In the first assessment, 980 primary students (F = 441, 45%; M = 539, 55%) from Grade 4 to 6 participated, of whom 786 (F = 358, 45.5%; M = 428, 54.5%) completed the follow-up survey, all of which were valid. The follow-up rate was satisfactory at 80.2%, and comprised 258 (32.8%), 267 (34.0%) and 261 (33.2%) of the Grade 4, 5 and 6 students, respectively. The students were aged between 8 and 13 years, with a mean and standard deviation of 9.93 and .91, respectively.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Positive Emotions

Positive emotions were assessed using the Chinese version of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule—Short Form (PANAS-SF) (Mackinnon et al. 1999), which was developed from the original PANAS scale (Watson et al. 1988). This adapted 10-item scale requires participants to indicate how often they have five positive emotions (i.e., excited, enthusiastic, inspired, attentive and active) during the ‘past 2 weeks’ on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very slightly or not at all, 5 = extremely). This scale has demonstrated good test–retest reliability and convergent and criterion-related validity and cross-cultural validity among various international samples (e.g., America, China, Hong Kong, Mexico) (Thompson 2007). The reliability of the scale in the current study was good (α = .80).

2.2.2 Positive Meaning and Study Engagement

In the current study, we adopted the measures of positive meaning and study engagement, matching the Assessment Programme for Affective and Social Outcomes (2nd Version) (APASO-II) with reference to Lai et al. (2018). APASO, developed in 2001 and revised in 2010, aimed to evaluate social and emotional outcomes in primary and secondary school students (Moore et al. 2006; Wu and Mok 2017). Good validity and reliability were established with a sample of 80,000 primary and 130,000 secondary students among 352 primary and secondary schools in Hong Kong (representing around 1/3 of all schools) (Wu and Mok 2017; Education Bureau HKSAR 2016). The dimensionality and internal consistency of these scales were presented as supporting evidence of their adequacy for evaluating a positive education programme in a previous study (Lai et al. 2018). As APASO-II is completed by students once a year and local norms have been developed, we aimed to cross-validate these measures for application in positive education, as it would be valuable if these results could be widely used for the evaluation of positive education programmes in the future.

Positive Meaning was assessed using the Chinese version of the Positive Meaning in School Scale (Lai et al. 2018). Fifteen items were used to measure three subscales – Experiences in School, Value of School Work and Education Aims – on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 4 (totally agree). Cronbach’s alpha in the present study for these three subscales was .89, .90 and .88, respectively.

Study Engagement was measured using the Chinese version of the Positive Engagement in Study Scale (Lai et al. 2018) which includes the subscales Perseverance, Effort Motivation and Task Motivation, evaluating aspects of vigour, dedication and absorption as suggested by Schaufeli et al. (2002). This is a 21-item scale using a 4-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree, 4 = totally agree). The reliability of each subscale in the present study was .84, .92 and .85, respectively. Details of the measures (i.e. positive meaning and study engagement) can be requested from the authors by email.

2.2.3 Strengths Use

Strengths use was evaluated using the Chinese version of the Strengths Use Scale (Govindji and Linley 2007), which comprises 14 items to assess the extent to which participants use their strengths in both school and daily life, ranging from 1 ‘strongly disagree’ to 7 ‘strongly agree’. Examples of the items were ‘I can regularly do what I do best’ and ‘I am able to use my strengths in different ways’. This is the only scale available to assess the use of rather than the prevalence of strengths. Good reliability and construct validity have been reported (Wood et al. 2011), and the current study demonstrated good internal consistency of the scale(α = .97).

2.3 Data Analysis

Fewer than 5% of the responses were missing due to participants omitting certain questionnaire items. Multiple imputations were applied to replace the missing data (Acock 2005) to retain the current sample size and reflect the responses of the participants more completely (Rubin 1996). The mean, standard deviation, Cronbach’s alpha and correlation were computed for each variable at both time points. Multicollinearity diagnostic analysis was also performed to ensure that the constructs did not convey essentially the same information. A measurement model (MM) was tested using confirmatory factor analysis (Kline 2015).

Several competing structural models were applied to investigate the proposed reciprocal effects. (1) The stability model (SM1) was used to estimate the stability coefficients (i.e., correlations between each construct itself at T1 and T2) and synchronous correlations without cross-lagged structural paths (Pitts et al. 1996). The fitness index of the stability model was compared to that of the following three more complex models: (2) the causality model (SM2), whose fundamental structure is identical to that of SM1 but was combined with the causal relationships as hypothesised in the theoretical framework to test hypotheses 1a, 2a, 3a, 4a and 4b (Fig. 2); (3) the reverse causation model (SM3), which is also identical to SM1 but included the additional reverse effects, to investigate hypotheses 1b, 2b, 3b, 4a and 4b (Fig. 3); and (4) the reciprocal model (SM4), which is a combination of SM2 and SM3, to examine all the hypotheses together (Fig. 4). A multigroup analysis was also performed based on gender differences.

All models were analysed using maximum likelihood estimation in SPSS AMOS 25.0 (Arbuckle 2012). The overall fit of the models was assessed with χ2 statistics and degrees of freedom (df), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), normed fit index (NFI) and goodness-of-fit index (GFI). The goodness-of-fit indices and criteria for good fit in models were indicated by a χ2/df value between 2 and 3. A cutoff at .90 has been suggested for an acceptable model fit and .95 or above as an excellent fit for the CFI, TLI, NFI and GFI (Hu and Bentler 1999). For RMSEA, a value smaller than .08 reflects acceptable model fit, and values greater than .10 should lead to model rejection (Browne and Cudeck 1993).

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive Statistics

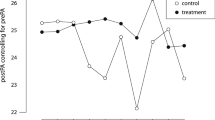

The attrition rate was 19.8% for the follow-up assessment. Attrition was examined using a logistic regression by regressing follow-up participation on all studied variables. No significant predictors of attrition were identified (all ps > .05), indicating that the longitudinal sample is representative of the total sample. In addition, no significant differences were found (all ps > .05) between the two schools and student age on all initial studied variables. However, significant differences were identified between genders at Time 1 for positive emotions (t = -2.63, p < .05), positive meaning (t = -3.24, p < .05) and study engagement (t = -2.85, p < .05). The mean, standard deviation and correlation matrix for all research variables at the two time points are reported in Table 1. All correlations were positive and significant. The variance inflation factors (VIF < 5) and tolerances (Tol > .20) from the multicollinearity diagnostic analysis showed that the measures of PE, PM, SU and SE were not redundant.

3.2 Measurement Model

Measurement model 1 (MM1) consisted of four latent constructs with two time points. Two latent variables, positive emotions and use of strengths, were indicated by three parcels formed by their own scale items (Bandalos 2002). Two other latent variables (i.e., positive meaning and study engagement) were manifested by the mean scores of their established subscales as indicators, as stated in the measures section. The proposed model showed a good fit to the data: χ2 (267) = 659.78; p < .001, RMSEA = .04 (90% CI = .03 – .05), CFI = .97, TLI = .96, NFI = .95. All standardised factor loadings for the latent variables were greater than λ = .66 and significant, indicating an adequate, valid and reliable measurement model. All details are presented in Tables 2 and 3.

3.3 Structural Model Test

Table 3 shows the fit indices of the four competing models. First, the causality model (SM2) fits the data significantly better than does the stability model ((SM1) (Δ χ2 (6) = 47.00, p < .001). The fit of the reverse causality model (SM3) is also superior to that of SM1 ((Δ χ2 (6) = 29.32, p < .001). Moreover, the reciprocal model (SM4) fits the data significantly better than do SM1, SM2 and SM3 (Table 3). This implies that the model including the reciprocal relationships is superior to all alternative models, Therefore, both causal and reversed causal relationships exist simultaneously, which is confirmed by the model fit of the reciprocal model SM4 (Table 3 and Fig. 5). SM4 explained 49% of the variance in PE at T2, 40% of the variance in PM at T2, 26% of SU at T2 and 42% of the variance in SE at T2.

Hypotheses 1a, 2a and 3a assume that PE at T1 are positively related to SE and PM at T2 while PM T1 are also positively correlated with SE at T2. The causality model (SM2) includes the abovementioned relationships, all three of which were found to be significant. The standardised effects of PE at T1 on SE at T2 (β = .16) and PM at T2 (β = .15) were significant, as was PM at T1 on SE at T2 (β = .24). Thus, Hypotheses 1a, 2a and 3a are supported. The students’ initial PE led to subsequent PM and SE, while their initial PM predicted subsequent SE.

Regarding hypotheses 1b, 2b and 3b, the results of SM3 indicated a significant reverse causal effect of PM at T1 on PE at T2 (β = .15, p < .05). However, no significant reverse effect was found between SE at T1 and PE at T2, or between SE at T1 and PM at T2. As such, hypothesis 1b is supported, indicating that PE and PM are reciprocally correlated. However, hypotheses 2b and 3b have to be rejected, indicating that students’ initial SE does not predict subsequent PE and PM.

In terms of hypotheses 4a and 4b, it is shown that PE at T1 was positively associated with SU at T2 (β = .17, p < .05) while SU at T1 was also positively correlated with SE at T2 (β = .12, p < .05). However, a non-significant effect was found between PM at T1 and SU at T2. Thus, hypothesis 4a is supported while 4b is rejected. That is, strengths use is a mediator in the association between positive emotion and study engagement, but not between meaning and engagement.

3.4 Multigroup Analysis Results: Gender Difference in the ARCL Model

To identify whether there is a gender difference in the relationships among the studied variables based on the ARCL model, we performed a multigroup analysis. Because the χ2 value is known to be highly sensitive to sample size, we adopted ΔCFI, ΔTLI and ΔRMSEA to further support the comparisons (Fornell and Larker 1981; McDonald and Ho 2002). We divided the final model (SM4) by gender and analysed each group to check for configural invariance. SM4 fitted equally well for both girls and boys and therefore configural invariance was satisfied, with path coefficients estimated in Fig. 5. We also checked the assumption of metric invariance between the genders by evaluating the factor loading values in group comparisons (Hong et al. 2010). Specifically, the base model was an invariant-unconstrained model based on SM4, and the metric invariance model did not differ significantly from the base model. Although a statistically significant χ2 difference score resulted from comparison with the factor pattern invariance model, little gain was found for either traditional or relative measures of fit (ΔCFI and ΔTLI < .01; RMSEA = .000) (Cheung and Rensvold 2002) (see Table 3). Therefore, we judged that the metric invariance assumption was satisfied. In addition, the structural invariance model satisfied the assumption of path invariance with little or no change in fit indices (ΔCFI and ΔTLI < .01; ΔRMSEA = .000). All these results indicated that there was no gender difference in the ARCL model.

4 Discussion

The present study investigated the interrelationships between positive emotions, meaning, study engagement and the potential mediating effect of strengths use. Our results indicate that initial positive emotions and meaning predict concurrent and subsequent study engagement. Positive emotions and meaning are reciprocally correlated with each other. Moreover, our findings support that use of strengths mediates the relationship between positive emotions and study engagement. These findings add to our understanding of the underlying mechanism by which positive emotions and meaning make people more engaged.

4.1 Unique Effects

First, our results replicate and extend previous research on the broaden-and-build theory that positive emotions are essential elements for optimal functioning (Fredrickson 2001). Our findings indicate that students who experience positive emotions initially are more likely to find positive meaning, use their strengths and show greater study engagement both concurrently and over time, in addition to greater physical and psychological well-being (Fredrickson 2003). Apparently, students with positive emotions may not only feel good about themselves, but are also able to mobilise their strengths, find purpose in learning and participate more at school. Also, as hypothesised and in line with the previous literature (Fox Eades et al. 2014), initial positive meaning is positively correlated with concurrent and subsequent study engagement. Specifically, when students feel that study is meaningful, their participation levels may increase, while positive outcomes are enhanced. Consequently, they are more willing to engage in study-related activities.

4.2 Reciprocal Effects

Our results confirm the theory-based hypothesis of reciprocal correlation between positive emotions and meaning. It is proposed that not only do positive emotions elicit positive meaning, but meaning also triggers positive emotions (Fredrickson 2000). On the one hand, the broadening effects of positive emotions produce a flexible mental state that enables students to create and pursue abstract and long-term goals. These goals may increase the likelihood of finding positive meaning in subsequent events (Fredrickson 2003). On the other hand, finding positive meaning may be the most powerful leverage point for cultivating positive emotions (Fredrickson 2005). For instance, feeling connected to others and being cared for can create love and joy, whereas pursuing and attaining realistic goals may lead to a sense of interest and contentment. In the long run, an ‘upward spiral’ may be initiated by this reciprocal relationship (Fredrickson and Joiner 2002).

4.3 Strengths use as a Mediator

The findings supported our hypothesis of the mediating role of strengths use, indicating that positive emotions facilitate the building of enduring personal resources (Fredrickson 2005), use of strengths in this study, and in turn promote study engagement across time (Bakker and Demerouti 2008). Traditionally, positive emotion has been considered an important factor in student participation to keep them interested and engaged in their studies (Fredrickson 2000). The present study goes one step further by showing that positive emotions may trigger the use of strengths both in school and in daily life, a kind of ‘personal resource’ in general, which facilitates students in gaining more initiative and feeling more capable of managing their studies. Presumably, as a result, they may be more confident and in turn stay engaged (Xanthopoulou et al. 2007). Therefore, this empirical evidence of the mediating effect of strengths use contributes significantly to our understanding of the underlying psychological mechanism.

The current study adds to the evidence on strengths-based research in positive education, indicating that deploying strengths is an important determinant of study engagement (e.g., Quinlan et al. 2012). The results demonstrated that students who constantly apply their strengths are most likely to experience high levels of study engagement. Specifically, it is argued that the use of strengths may provide students with positive feedback and the experience of mastery, which further stimulate their willingness and ability to manage the challenges of future study (Bakker and Demerouti 2008). Consequently, they are more likely to engage and excel in attaining their study goals (van Woerkom et al. 2016).

The results of this study indicate no significant gender differences in the associations between the studied variables. The reciprocal relationship between positive emotions and meaning is equally strong in both the boys’ and the girls’ groups. Moreover, the mediating effects of strengths use are roughly the same in both groups. This could be explained by the reason that both boys and girls at this stage of school have similar developmental tasks valued by society, with reference to Eric Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development (i.e., industry vs inferiority). Specifically, the primary students may not show significant differences yet because they are still learning to identify and manage their emotions, exploring their own study meaning and piloting the application of their personal strengths.

Taken altogether, regardless of gender, students in primary schools who experience more frequent positive emotions in schools are more likely to find positive meaning and use their strengths, so that they are more willing to engage in education-related activities over time. More importantly, the implication is that the constructs included in the current study cannot be interpreted in isolation as hypothetical antecedents or outcomes because reciprocal causation seems to occur. Rather, these psychological processes are dynamic. However, it should be noted that there was no significant increase in the levels of the variables over time. Thus, although our study supports the idea of reciprocal relations, it does not suggest an upward spiral, in contrast to current theory (Fredrickson and Joiner 2002). In other words, it cannot be deduced from our findings that the occurrence of positive emotions and meaning lead to higher levels of positive emotions and meaning. Nevertheless, this does not downgrade the importance of the present study, which indicates that the reciprocal effects of positive emotion and meaning may activate subsequent strengths use and study engagement.

In terms of the non-significant result that initial engagement does not predict subsequent positive emotions and meaning, we would try to understand it through the cultural perspective. The culture of collectivism in the East Asian community promotes the greater cause and prosperity of the collective (e.g. showing ‘filial piety’ and bringing ‘honour to one’s ancestors’ in the family while ‘studying for the rise of China’ for the country), even at a cost to one’s personal welfare (Lu and Gilmour 2006). Thus, students diligently carry out their moral duty to study and contribute for the family and society, which best captures the essence of the East Asian cultural conception of ‘study’ (Kitayama and Markus 2000). Therefore, Chinese students may engage because they are obliged to rather than truly willing to. Thus, rather than feeling happy, they may feel pressured or even burdened while they are engaged, and not generate positive meaning from these passive obligations. Future research is needed to explore these proposed cultural differences.

5 Limitations

Despite obtaining interesting results, this study has certain limitations. One limitation is the use of self-report measures only, although perceptions may be more important than objective reality for understanding what students feel, think and do (Wood et al. 2011). However, we cannot entirely avoid the risk of common method bias, which may inflate the relationships between variables. Nevertheless, the longitudinal design overcomes some of these problems because previous levels of the variables are controlled for to a certain degree (Doty and Glick 1998). Second, although our study design alleviates the weakness of common method bias (Podsakoff et al. 2003), the mediated process model was tested at only two time points. More comprehensive testing would require at least three waves (van Woerkom et al. 2016). Third, despite the two-wave cross-lagged design, strictly speaking, it cannot offer definite evidence for causality; especially when the relationship between the two examined constructs is reciprocal, as a third variable may cause both constructs’ covariance. As a result, other factors (e.g., positive relationships, teacher support and the school environment) could be further explored to gain a more comprehensive view. We will include several contextual factors (i.e., teacher performance, classroom climate and school atmosphere) in our upcoming studies. Finally, as our participants were primary school students who are relatively young, our results and conclusions may not be generalisable to older student populations. Nevertheless, the present study advances our knowledge of the dynamic relations among the studied variables, which have important implications.

6 Implications

The current study has implications for promoting positive education among primary school students. Because engagement is an essential and positive element of study, it is important to initiate and maintain study engagement over time. This may be sparked by positive emotions, meaning and the use of strengths. First, intervention strategies may focus more on the experience of positive emotions. Studies indicate that making efforts to think about things we are grateful for and generate tenderness and compassion for others lead to an increase in positive emotions (Fredrickson and Kurtz 2011). For instance, practising loving kindness, meditation and gratitude are helpful in creating positive emotional experiences and life satisfaction (Fredrickson et al. 2008; Kwok et al. 2016). Second, people may find positive meaning within ordinary daily events and activities at school or at home by reframing or infusing them with positive values. Daily experiences of gaining positive meaning come in several forms, such as creating high-quality connections with others, feeling cared about, experiencing a sense of achievement or self-esteem and generating hope or optimism (Fredrickson 2000). Third, it is suggested that the use of strengths may be beneficial for students. Interventions can try to encourage students to identify, foster and apply appropriate usages of their strengths as drivers of study engagement. Teachers can enhance the use of strengths by providing positive feedback whenever students deploy their strengths appropriately, both in school and daily life. That is, instead of automatically translating their weaknesses into learning goals, teachers may emphasise methods to develop students towards an ideal level which may lead to more positive outcomes (Ouweneel et al. 2011).

7 Conclusion

The present study shows that positive emotions and positive meaning are reciprocally related to each other and subsequently promote study engagement across time, and that strengths use mediates the association between positive emotion and study engagement.

References

Acock, A. C. (2005). Working with missing values. Journal of Marriage and family, 67(4), 1012–1028.

Arbuckle, J. (2012). IBM SPSS AMOS (Version 21.0)[Computer Program]. Chicago, US: IBM.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2008). Towards a model of work engagement. Career Development International, 13(3), 209–223.

Bandalos, D. L. (2002). The effects of item parceling on goodness-of-fit and parameter estimate bias in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(1), 78–102.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sage Focus Editions, 154, 136–136.

Cacioppo, J. T., Gardner, W. L., & Berntson, G. G. (1999). The affect system has parallel and integrative processing components: Form follows function. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(5), 839.

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255.

Christopher, J. C., & Hickinbottom, S. (2008). Positive psychology, ethnocentrism, and the disguised ideology of individualism. Theory and Psychology, 18(5), 563–589.

Crabb, S. (2011). The use of coaching principles to foster employee engagement. The Coaching Psychologist, 7(1), 27–34.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). Toward a psychology of optimal experience. In Flow and the foundations of positive psychology (pp. 209–226). Springer.

Doty, D. H., & Glick, W. H. (1998). Common methods bias: does common methods variance really bias results? Organizational Research Methods, 1(4), 374–406.

Education Bureau HKSAR (2016). Assessment Program for Affective and Social Outcomes (2nd Version) (APASO-II). Retrieved March 25, 2019, from https://www.edb.gov.hk/en/sch-admin/sch-quality-assurance/performance-indicators/apaso2/index.html.

Fornell, C., & Larker, D. (1981). Structural equation modeling and regression: guidelines for research practice. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Fox Eades, J. M., Proctor, C., & Ashley, M. (2014). Happiness in the classroom. In S. A. David, I. Boniwell, & A. C. Ayers (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of happiness (pp. 579–591). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109.

Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 300–319.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2000). Cultivating positive emotions to optimize health and well-being. Prevention and Treatment, 3(1), 1a.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2003). The value of positive emotions: The emerging science of positive psychology is coming to understand why it’s good to feel good. American Scientist, 91(4), 330–335.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2005). Positive emotion. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Oxford handbook of positive psychology (p. 130). Oxford: Oxford library of psychology.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Branigan, C. (2005). Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cognition and Emotion, 19(3), 313–332.

Fredrickson, B. L., Cohn, M. A., Coffey, K. A., Pek, J., & Finkel, S. M. (2008). Open hearts build lives: positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(5), 1045–1062.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Joiner, T. (2002). Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional well-being. Psychological Science, 13(2), 172–175.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Kurtz, L. E. (2011). Cultivating positive emotions to enhance human flourishing (pp. 35–47). Applied Positive Psychology: Improving everyday life, health, schools, work, and society.

Govindji, R., & Linley, P. A. (2007). Strengths use, self-concordance and well-being: Implications for strengths coaching and coaching psychologists. International Coaching Psychology Review, 2(2), 143–153.

Hong, S., Yoo, S.-K., You, S., & Wu, C.-C. (2010). The reciprocal relationship between parental involvement and mathematics achievement: Autoregressive cross-lagged modeling. The Journal of Experimental Education, 78(4), 419–439.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55.

Kadha, H. M. (2009). What makes a good english language teacher?’Teachers’ perceptions and students’ conceptions. Humanity and Social Sciences Journal, 4(11), 1–11.

King, L. A., Hicks, J. A., Krull, J. L., & Del Gaiso, A. K. (2006). Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(1), 179.

Kitayama, S., & Markus, H. R. (2000). The pursuit of happiness and the realization of sympathy: Cultural patterns of self, social relations, and well-being. In Culture and Subjective Well-Being (pp. 113–161).

Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling: Guilford publications.

Kwok, S. Y. C., & Gu, M. (2017). The role of emotional competence in the association between optimism and depression among Chinese adolescents. Child Indicators Research, 10(1), 171–185.

Kwok, S. Y. C., Gu, M., & Tong, K. K. K. (2016). Positive psychology intervention to alleviate child depression and increase life satisfaction: A randomized clinical trial. Research on Social Work Practice, 26(4), 350–361.

Kwok, S. Y. C., Yeung, J. W. K., Low, A. Y. T., Lo, H. H. M., & Tam, C. H. L. (2015). The roles of emotional competence and social problem-solving in the relationship between physical abuse and adolescent suicidal ideation in China. Child Abuse and Neglect, 44, 117–129.

Lai, M. K., Leung, C., Kwok, S. Y., Hui, A. N., Lo, H. H., Leung, J. T., et al. (2018). A multidimensional PERMA-H positive education model, general satisfaction of school life, and character strengths use in Hong Kong senior primary school students: Confirmatory factor analysis and path analysis using the APASO-II. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1090.

Lee, V. E. (1996). The influence of school climate on gender differences in the achievement and engagement of young adolescents.

Lewis, A. D., Huebner, E. S., Malone, P. S., & Valois, R. F. (2011). Life satisfaction and student engagement in adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(3), 249–262.

Li, Y., & Lerner, R. M. (2011). Trajectories of school engagement during adolescence: Implications for grades, depression, delinquency, and substance use. Developmental Psychology, 47(1), 233–247.

Linkins, M., Niemiec, R. M., Gillham, J., & Mayerson, D. (2015). Through the lens of strength: A framework for educating the heart. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(1), 64–68.

Linley, P. A. (2008). Average to A. Realising strengths in yourself and others.

Linley, P. A., & Harrington, S. (2006). Playing to your strengths. Psychologist, 19(2), 86–89.

Lu, L., & Gilmour, R. (2006). Individual-oriented and socially oriented cultural conceptions of subjective well-being: Conceptual analysis and scale development. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 9(1), 36–49.

Mackinnon, A., Jorm, A. F., Christensen, H., Korten, A. E., Jacomb, P. A., & Rodgers, B. (1999). A short form of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule: Evaluation of factorial validity and invariance across demographic variables in a community sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 27(3), 405–416.

May, D. R., Gilson, R. L., & Harter, L. M. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77(1), 11–37.

McDonald, R. P., & Ho, M.-H. R. (2002). Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 64.

Mendes, F., & Stander, M. W. (2011). Positive organisation: The role of leader behaviour in work engagement and retention. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 37(1), 1–13.

Moore, P. J., Mok, M. C. M., Chan, L. K., & Yin, L. P. (2006). The development of an indicator system for the affective and social schooling outcomes for primary and secondary students in Hong Kong. Educational Psychology, 26(2), 273–301.

O’Farrell, S. L., & Morrison, G. M. (2003). A factor analysis exploring school bonding and related constructs among upper elementary students. The California School Psychologist, 8(1), 53–72.

Ouweneel, E., Le Blanc, P. M., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2011). Flourishing students: A longitudinal study on positive emotions, personal resources, and study engagement. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(2), 142–153.

Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2007). Methodological issues in positive psychology and the assessment of character strengths. In A. D. Ong & M. H. M. van Dulmen (Eds.), Handbook of methods in positive psychology (pp. 292–305). New York: Oxford University Press.

Pitts, S. C., West, S. G., & Tein, J.-Y. (1996). Longitudinal measurement models in evaluation research: Examining stability and change. Evaluation and Program Planning, 19(4), 333–350.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879.

Proctor, C., Maltby, J., & Linley, P. A. (2011). Strengths use as a predictor of well-being and health-related quality of life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12(1), 153–169.

Quinlan, D., Swain, N., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2012). Character strengths interventions: Building on what we know for improved outcomes. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13(6), 1145–1163.

Reschly, A. L., Huebner, E. S., Appleton, J. J., & Antaramian, S. (2008). Engagement as flourishing: The contribution of positive emotions and coping to adolescents’ engagement at school and with learning. Psychology in the Schools, 45(5), 419–431.

Rubin, D. B. (1996). Multiple imputation after 18 + years. Journal of the American statistical Association, 91(434), 473–489.

Salanova, M., Llorens, S., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2011). “Yes, I can, I feel good, and I just do it!” On gain cycles and spirals of efficacy beliefs, affect, and engagement. Applied Psychology, 60(2), 255–285.

Salanova, M., Schaufeli, W., Martínez, I., & Bresó, E. (2010a). How obstacles and facilitators predict academic performance: The mediating role of study burnout and engagement. Anxiety Stress and Coping, 23(1), 53–70.

Salanova, M., Schaufeli, W. B., Xanthopoulou, D., & Bakker, A. B. (2010b). The gain spiral of resources and work engagement: Sustaining a positive worklife. In Work engagement: A handbook of essential theory and research (pp. 118–131).

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 25(3), 293–315.

Schaufeli, W. B., Martinez, I. M., Pinto, A. M., Salanova, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). Burnout and engagement in university students: A cross-national study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33(5), 464–481.

Schueller, S. M., & Seligman, M. E. (2010). Pursuit of pleasure, engagement, and meaning: Relationships to subjective and objective measures of well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(4), 253–263.

Seligman, M. E. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment: Simon and Schuster.

Seligman, M. E. (2012). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York: The Free Press.

Seligman, M. E., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction (Vol. 55, Vol. 1): American Psychological Association.

Seligman, M. E., & Royzman, E. (2003). Happiness: The three traditional theories. Authentic Happiness Newsletter.

Shernoff, D. J., Csikszentmihalyi, M., Schneider, B., & Shernoff, E. S. (2003). Student engagement in high school classrooms from the perspective of flow theory. In Applications of flow in human development and education (pp. 475–494): Springer.

Steger, M. F., Littman-Ovadia, H., Miller, M., Menger, L., & Rothmann, S. (2013). Engaging in work even when it is meaningless: Positive affective disposition and meaningful work interact in relation to work engagement. Journal of Career Assessment, 21(2), 348–361.

Thompson, E. R. (2007). Development and validation of an internationally reliable short-form of the positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS). Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 38(2), 227–242.

Upadyaya, K., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2013). Development of school engagement in association with academic success and well-being in varying social contexts: A review of empirical research. European Psychologist, 18(2), 136.

van Woerkom, M., Oerlemans, W., & Bakker, A. B. (2016). Strengths use and work engagement: A weekly diary study. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 25(3), 384–397.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063.

Weber, M., Wagner, L., & Ruch, W. (2016). Positive feelings at school: On the relationships between students’ character strengths, school-related affect, and school functioning. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(1), 341–355.

Wilkins, B., Boman, P., & Mergler, A. (2015). Positive psychological strengths and school engagement in primary school children. Cogent Education, 2(1), 1095680.

Wood, A. M., Linley, P. A., Maltby, J., Kashdan, T. B., & Hurling, R. (2011). Using personal and psychological strengths leads to increases in well-being over time: A longitudinal study and the development of the strengths use questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(1), 15–19.

Wu, G. K. Y., & Mok, M. M. C. (2017). Social and emotional learning and personal best goals in Hong Kong. In Social and Emotional Learning in Australia and the Asia-Pacific (pp. 219–231): Springer.

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2007). The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. International Journal of Stress Management, 14(2), 121.

Funding

The project is funded by Bei Shan Tang Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kwok, S.Y.C.L., Fang, S. A Cross-Lagged Panel Study Examining the Reciprocal Relationships Between Positive Emotions, Meaning, Strengths use and Study Engagement in Primary School Students. J Happiness Stud 22, 1033–1053 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00262-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00262-4