Abstract

The improving strength of the labor market is chiefly responsible for the overall increase in life satisfaction in urban China from 2002 to 2012. This is especially true for the segment of the population most vulnerable to the negative effects of the on-going transition to a free-market based economy—people with less than a college education. Income comparison and habituation effects offset any positive effect of increased personal income during this time. The result is that increases in income are not significantly related to the increase in life satisfaction during this time. In the interest of protecting the life satisfaction of those most vulnerable, attention must be paid to maintaining a strong labor market as internal migration restrictions are loosened and the labor market is further liberalized in China. These findings are based on repeated cross-sectional data spanning from surveys used in the annual economic reports published by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. A modified version of the Oaxaca decomposition method is developed to take advantage of annual data and also control for adaptation to income effects. The change in life satisfaction from 2002 to 2012 is then divided into segments associated with changes in various life domains.

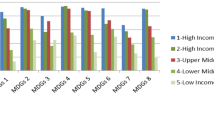

Source: HRCG data used in analysis

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Cities of survey were determined first. Then, within each city, the central district along with other randomly selected districts were targeted for sampling. Communities within the selected districts were randomly chosen for sampling. Finally, households in a selected community were randomly chosen according to the rule of “sampling one household after passing by five households”. One respondent was randomly determined within each selected household to complete the survey.

Another reason of dropping the rural sample is that selected rural villages were generally incomparable over time, and for some years, rural surveys were not conducted.

The seven cities are not representative of urban China. Nevertheless, the data includes typical cities in all regions of China. Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Wuhan, Shenyang, Xi’an, and Chengdu belong to North China, East China, South China, Central-south China, Northeast China, Northwest China and Southwest China.

In this paper, the term “subjective well-being” is used to refer to self-reported evaluations of a person’s happiness or satisfaction with life. These measures are considered comparable because they correlate with the same explanatory variables (Helliwell et al. 2012).

City dummies and year dummies capture all regional and temporal factors, including demographic structures, socio-economic development, public policies, and so on, that might be related to individual subjective well-being. For example, Huang (2018) finds that city-level income inequality significantly affects individual happiness.

Household size is not controlled in analyses because only a couple of years of surveys include this variable. For the years with household size, results are similar no matter if household size is considered or not.

Original income categories varied by year, and were unified to the same set of categories. Continuous measures of income were not recorded in the data.

There are 56 groups in each year. Groups cannot be smaller as the sample size of a group would be too small to generate reliable statistics.

The previous income of respondents in 2007 is their predicted income in 2005.

Clark et al. (2008) offer a review.

Different age group dummies were inserted into the analysis for robustness checks. The results did not change.

The sample of year 2001 will be only used to generate the previous income of year 2002.

In the pooled cross-sectional regression \(\widehat{LS}_{i,t} = \varvec{x}_{i,t} \widehat{\beta } = \varvec{z}_{i,t} \widehat{\varvec{\gamma}} + \sum_{t = 2001}^{2012} d_{t} \widehat{\delta }_{t}\), where \(d_{t}\) is a dummy for year t, \(\hat{\delta }_{t}\) will be chosen, by construction, so \(\overline{{\widehat{LS}}}_{t} = \overline{LS}_{t}\) for each t.

"Appendix 3" details how p values were calculated.

Hukou status reflects if a person is registered as an urban or rural resident. People residing in urban areas with rural hukou status are migrants from rural areas in China.

References

Appleton, S., & Song, L. (2008). Life satisfaction in Urban China: Components and determinants. World Development,36(11), 2325–2340.

Arampatzi, E., Burger, M. J., & Veenhoven, R. (2015). Financial distress and happiness of employees in times of economic crisis. Applied Economic Letters,22(3), 173–179.

Bartolini, S., & Sarracino, F. (2015). The dark side of Chinese growth: Declining social capital and well-being in times of economic boom. World Development,74, 333–351.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2004). Well-being over time in Britain and the USA. Journal of Public Economics,88(7), 1359–1386.

Brockmann, H., Delhey, J., Welzel, C., & Yuan, H. (2009). The China puzzle: Falling happiness in a rising economy. Journal of Happiness Studies,10(4), 387–405.

Burkholder, R. (2005). Chinese far wealthier than a decade ago—But are they happier. The Gallup Organization,30, 2007.

Cai, H., Chen, Y., & Zhou, L. A. (2010a). Income and consumption inequality in urban China: 1992–2003. Economic Development and Cultural Change,58(3), 385–413.

Cai, F., Wang, M. Y., & Wang, D. W. (Eds.). (2010b). The China population and labor yearbook: The sustainability of economic growth from the perspective of human resources (Vol. 2). Leiden: Brill.

Cantril, H. (1965). The pattern of human concerns. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Chen, J. G., Liu, S. C., & Wang, T. S. (Eds.). (2011). The China economy yearbook: Analysis and forecast of China’s economic situation (Vol. 5). Leiden: Brill.

Clark, A., Georgellis, Y., & Sanfey, P. (2001). Scarring: The psychological impact of past unemployment. Economica,68(270), 221–241.

Clark, A. E., Frijters, P., & Shields, M. A. (2008). Relative income, happiness, and utility: An explanation for the easterlin paradox and other puzzles. Journal of Economic Literature,46(1), 95–144.

Crabtree, S., & Wu, T. (2011). China’s puzzling flat line. Gallup Management Journal. Available at: http://gmj.gallup.com/content/148853/china-puzzling-flat-line.aspx#1. Accessed February 1, 2012.

D’Ambrosio, C., & Frick, J. R. (2007). Income satisfaction and relative deprivation: An empirical link. Social Indicators Research,81(3), 497–519.

D’Ambrosio, C., & Frick, J. R. (2012). Individual wellbeing in a dynamic perspective. Economica,79(314), 284–302.

Di Tella, R., Haisken-De New, J., & MacCulloch, R. (2010). Happiness adaptation to income and to status in an individual panel. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization,76(3), 834–852.

Di Tella, R., MacCulloch, R. J., & Oswald, A. J. (2003). The macroeconomics of happiness. Review of Economic Statistics,85(4), 809–827.

Easterlin, R. A. (2003). Explaining happiness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,100(19), 11176–11183.

Easterlin, R. A. (2010). Happiness, growth, and the life cycle. New York: Oxford University Press.

Easterlin, R. A., McVey, L. A., Switek, M., Sawangfa, O., & Zweig, J. S. (2010). The happiness-income paradox revisited. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,107(52), 22463–22468.

Easterlin, R. A., Morgan, R., Switek, M., & Wang, F. (2012). China’s life satisfaction, 1990–2010. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences,109(25), 9775–9780.

Easterlin, R. A., Wang, F., & Wang, S. (2017). Growth and happiness in China. In J. Helliwell, R. Layard, & J. Sachs (Eds.), World happiness report 2017 (pp. 1990–2015). New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

Graham, C., Zhou, S., & Zhang, J. (2017). Happiness and health in China: The paradox of progress. World Development,96, 231–244.

Gustafsson, B., & Ding, S. (2013). Unemployment and the rising number of non-workers in urban China: Causes and distributional consequences. In S. Li, H. Sato, & T. Sicular (Eds.), Rising inequality in China: Challenges to a harmonious society (pp. 289–331). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Helliwell, J. F., Layard, R., & Sachs, J. (2012). World happiness report 2012. New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

Helliwell, J. F., Layard, R., & Sachs, J. (2013). World happiness report 2013. New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

Huang, J. (2018). Income inequality, distributive justice beliefs, and happiness in China: Evidence from a nationwide survey. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-1905-4.

Kahneman, D., & Krueger, A. B. (2006). Developments in the measurement of subjective well-being. The Journal of Economic Perspectives,20(1), 3–24.

Kassenboehmer, S. C., & Haisken-DeNew, J. P. (2009). You’re fired! The causal negative effect of entry unemployment on life satisfaction. The Economic Journal,119(536), 448–462.

Keller, T. (2018). Caught in the monkey trap: Elaborating the hypothesis for why income aspiration decreases life satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-9969-z.

Knight, J., & Gunatilaka, R. (2011). Does economic growth raise happiness in China? Oxford Development Studies,39(01), 1–24.

Knight, J., & Xue, J. (2006). How high is urban unemployment in China? Journal of Chinese Economic and Business Studies,4(2), 91–107.

Knight, J. B., & Song, L. (2005). Towards a labour market in China. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lu, M., & Gao, H. (2011). Labour market transition, income inequality and economic growth in China. International Labour Review,150(1/2), 101–126.

Lucas, R. E., Clark, A. E., Georgellis, Y., & Diener, E. (2004). Unemployment alters the set point for life satisfaction. Psychological Science,15(1), 8–13.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2010). OECD Economic Surveys: China 2010. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-chn-2010-en.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2015). OECD Economic Surveys: China 2015. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-chn-2015-en.

Oshio, T., Nozaki, K., & Kobayashi, M. (2011). Relative income and happiness in Asia: Evidence from nationwide surveys in China, Japan, and Korea. Social Indicators Research,104, 351–367.

Smyth, R., & Qian, X. (2008). Inequality and happiness in urban China. Economics Bulletin,4(23), 1–10.

Stiglitz, J. E., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J. P. (2009). Report of the commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress. Available at: www.stiglitz-sen-fitoussi.fr. Accessed October 20, 2011.

Vendrik, M. C. (2013). Adaptation, anticipation and social interaction in happiness: An integrated error-correction approach. Journal of Public Economics,105, 131–149.

Wang, P., & Vander Weele, T. J. (2011). Empirical research on factors related to the subjective well-being of Chinese urban residents. Social Indicators Research,101(3), 447–459.

Wang, S., & Zhou, W. (2017). The unintended long-term consequences of Mao’s mass send-down movement: Marriage, social network, and happiness. World Development,90, 344–359.

Winkelmann, L., & Winkelmann, R. (1998). Why are the unemployed so unhappy? Evidence from panel data. Economica,65(257), 1–15.

Wolfers, J. (2003). Is business cycle volatility costly? Evidence from surveys of subjective well-being. International Finance,6(1), 1–26.

World Values Survey. (2014). WVS database. Available at: http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/. Accessed February 2015.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. P01AG022481); and Renmin University of China (Grant N. 581515101121).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendices

Appendix 1

See Table 6.

Appendix 2: Equivalence of Oaxaca Decomposition and This Paper’s Approach

The specification of the pooled cross-sectional regression used in the paper is

where \(d_{t}\) is a dummy for year t.

To implement Oaxaca decomposition, we run regressions for the years of 2002 and 2012, respectively, based on the same specification as in Eq. (4). Then, we have

where \(\widehat{\alpha }\) is the estimate of constant.

Then, the Oaxaca decomposition can be expressed as

where the second and third lines of Eq. (6) represent the Oaxaca decomposition with different base years, and the last line is an improved version of Oaxaca decomposition which avoids the issue of double base years. We assume \(\widehat{\varvec{\gamma}}\) is obtained from Eq. (4).

According to Eq. (4),

By comparing Eqs. (6) and (7), we can find that, the contribution of survey year dummies in (7), \(\hat{\delta }_{2012} - \hat{\delta }_{2002}\), is equivalent to the contribution of the regression coefficients in (6), and the rest parts, the contribution of the change in the values of variables are identical between (6) and (7).

The shortcoming of the approach in the paper compared to Oaxaca decomposition is that the former cannot distinguish the contribution of the change in each regression coefficient. However, the former could be acceptable if the total contribution of regression coefficients is relatively small, which is the case in the paper, or the study cares more about the contribution of the change in variable values.

Appendix 3: Calculation of p Values Reported in Tables 3 and 4

The p value of the percent contribution of variable \(x_{k}\) is derived from the following test.

H0 percent contribution of \(x_{k}\) = 0.

H1 percent contribution of \(x_{k}\) is not 0.

As the contribution of \(x_{k}\) is calculated from \(c_{k} = \frac{{\left( {\bar{x}_{k,2012} - \bar{x}_{k,2002} } \right)\hat{\beta }_{k} }}{{\Delta \overline{LS} }} \times 100\%\), it is equivalent to test if \(\beta_{k}\) is 0, conditional on the changes in life satisfaction (\(\Delta \overline{LS}\)) and in explanatory variables (\(\bar{x}_{k,2012} - \bar{x}_{k,2002}\)), or treating the two as constant.

If the percent contribution is calculated from the summation of many \(c_{k}\) (e.g., the percent contribution of age is equal to the summation of contributions of each age dummy), i.e., \(\sum c_{k} = \frac{{\sum \left( {\bar{x}_{k,2012} - \bar{x}_{k,2002} } \right)\hat{\beta }_{k} }}{{\Delta \overline{LS} }} \times 100\%\), then the p value is from the test whether \(\sum \left( {\bar{x}_{k,2012} - \bar{x}_{k,2002} } \right)\beta_{k}\) is 0, assuming \(\Delta \overline{LS}\) and each \(\left( {\bar{x}_{k,2012} - \bar{x}_{k,2002} } \right)\) are constant (or conditional on them).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Morgan, R., Wang, F. Well-Being in Transition: Life Satisfaction in Urban China from 2002 to 2012. J Happiness Stud 20, 2609–2629 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-0061-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-0061-5