Abstract

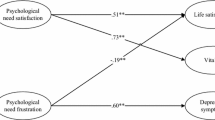

Although numerous studies have demonstrated the hedonic benefits of spending money on life experiences instead of material possessions, there has been no attempt to determine how different motivations for experiential consumption relate to psychological need satisfaction and well-being. Across five studies (N = 931), guided by self-determination theory, we developed a reliable and valid measure of motivation for experiential consumption—the Motivation for Experiential Buying Scale—to test these relations. Those who spend money on life experience for autonomous reasons (e.g., “because they are an integral part of my life”) report more autonomy, competence, relatedness, flourishing, and vitality; however, those who spend money on life experiences for controlled (e.g., “for the recognition I’ll get from others”) or amotivated reasons (e.g., “I don’t really know”) reported less autonomy, competence, and relatedness. These results demonstrated that the benefits of experiential consumption depend on why one buys life experiences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Throughout the article, we use the terms “experiential consumption,” “experiential purchase(s),” “spending money on life experiences,” “experiential buying,” and “buying life experiences” interchangeably.

For clarification, we present the six items intended to measure introjected regulation here: “I feel an increase in self-esteem from the experience,” “I would feel bad if I didn’t purchase the experience,” “I would feel guilty if I didn’t purchase the experience,” “I would feel anxious if I didn’t purchase the experience,” “Buying this experience makes me feel good about myself,” “Because it is important to buy such things.” The original 43-items are available upon request from the first author.

References

Assor, A., Vansteenkiste, M., & Kaplan, A. (2009). Identified versus introjected approach and introjected avoidance motivations in school and in sports: The limited benefits of self-worth strivings. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101, 482–497.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529.

Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588–606.

Brown, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Busseri, M. A., & Sadava, S. W. (2011). A review of the tripartite structure of subjective well-being: Implications for conceptualization, operationalization, analysis, and synthesis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(3), 290–314.

Caprariello, P. A., & Reis, H. T. (2010). To do with others or to have (or to do alone)? The value of experiences over material possessions depends on the involvement of others. Advances in Consumer Research, 37, 762–763.

Carter, T. J., & Gilovich, T. (2010). The relative relativity of material and experiential purchases. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(1), 146–159.

Carter, T. J., & Gilovich, T. (2012). I am what I do, not what I have: The differential centrality of experiential and material purchases to the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(6), 1304–1317.

Cattell, R. B. (1969). Comparing factor traits and state scores across ages and cultures. Journal of Gerontology, 24(3), 348–360.

Cronbach, L. J., & Meehl, P. E. (1955). Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin, 52(4), 281–302.

deCharm, R. (1968). Personal causation. New York: Academic Press.

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (1999). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125(6), 627–668.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2004). An overview of self-determination theory. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 3–33). Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology, 49(3), 182–185.

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., et al. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97(2), 143–156.

Dunn, E. W., Gilbert, D. T., & Wilson, T. D. (2011). If money doesn’t make you happy, then you probably aren’t spending it right. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 21, 115–125.

Fromm, E. (1976). To have or to be?. New York: Harper & Row.

Gagné, M. (2003). The role of autonomy support and autonomy orientation in prosocial behavior engagement. Motivation and Emotion, 27, 199–223.

Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Swann, W. B., Jr. (2003). A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality, 37, 504–528.

Guay, F., Vallerand, R. J., & Blanchard, C. (2000). On the assessment of situational intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: The situational motivation scale (SIMS). Motivation and Emotion, 24(3), 175–213.

Henson, R. K., & Roberts, J. K. (2006). Use of exploratory factor analysis in published research: Common errors and some comment on improved practice. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66, 393–416.

Howell, R. T., Chenot, D., Hill, G., & Howell, C. J. (2011). Momentary happiness: The role of psychological need satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12(1), 1–15.

Howell, R. T., & Hill, G. (2009). The mediators of experiential purchases: Determining the impact of psychological needs satisfaction and social comparison. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(6), 511–522.

Howell, R. T., & Howell, C. J. (2008). The relation of economic status to subjective well-being in developing countries: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 134(4), 536–560.

Howell, R. T., Pchelin, P., & Iyer, R. (2012). The preference for experiences over possessions: Measurement and construct validation of the experiential buying tendency scale. Journal of Positive Psychology, 7, 57–71.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternative. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55.

Hutcheson, G., & Sofroniou, N. (1999). The multivariate social scientist: Introductory statistics using generalized linear models. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Kasser, T. (2002). Sketches for a self-determination theory of values. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 123–140). Rochester, NY, USA: University of Rochester Press.

Kasser, T., Ryan, R. M., Couchman, C. E., & Sheldon, K. M. (2004). Materialistic values: Their causes and consequences. In T. Kasser & A. D. Kanfer (Eds.), Psychology and consumer cultures: The struggle for a good life in a materialistic world (pp. 11–28). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Landau, E. (2009). Study: Experiences make us happier than possessions. Retrieved from http://articles.cnn.com/2009-02-10/health/happiness.possessions_1_leaf-van-boven-experiences-psychological-research?_s=PM:HEALTH.

Mallett, C., Kawabata, M., Newcombe, P., Otero-Forero, A., & Jackson, S. (2007). Sport motivation scale-6 (SMS-6): A revised six-factor sport motivation scale. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 8, 600–614.

Marsh, H. W., Balla, J. R., & McDonald, R. P. (1988). Goodness-of-fit indexes in confirmatory factor analysis: The effect of sample size. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 391–410.

McDonald, R. P., & Marsh, H. W. (1990). Choosing a multivariate model: Noncentrality and goodness of fit. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 247–255.

Millar, M., & Thomas, R. (2009). Discretionary activity and happiness: The role of materialism. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(4), 699–702.

Nicolao, L., Irwin, J. R., & Goodman, J. K. (2009). Happiness for sale: Do experiential purchases make consumers happier than material purchases? Journal of Consumer Research, 36, 188–198.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

O’Connor, B. P. (2000). SPSS and SAS programs for determining the number of component using parallel analysis and velicer’s MAP test. Behavior Research Methods, Instrumentation, and Computers, 32, 396–402.

Patil, V. H., Surendra, N. S., Sanjay, M., & Donavan, D. T. (2007). Parallel analysis engine to aid determining number of factors to retain [Computer software]. Available from: http://ires.ku.edu/~smishra/parallelengine.html.

Paulhus, D. L., & Vazire, S. (2007). The self-report method. In R. W. Robins, R. C. Fraley, & R. F. Krueger (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in personality psychology (pp. 224–239). New York: Guilford.

Pelletier, L. G., Fortier, M. S., Vallerand, R. J., Tucson, K. M., Briere, N. M., & Blais, M. R. (1995). Toward a new measure of intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and amotivation in sports: The sport motivation scale (SMS). Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 17, 35–53.

Pelletier, L. G., Tuson, K. M., Green-Demers, I., Noels, K., & Beaton, A. M. (1998). Why are you doing things for the environment? The motivation toward the environment scale. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28(5), 437–468.

Pelletier, L. G., Tuson, K. M., & Haddad, N. K. (1997). Client motivation for therapy scale: A measure of intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and amotivation for therapy. Journal of Personality Assessment, 68(2), 414–435.

Rammstedt, B., & John, O. P. (2007). Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the big five inventory in English and German. Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 203–212.

Reis, H. T., Sheldon, K. M., Gable, S. L., Roscoe, J., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). Daily well-being: The role of autonomy, competence and relatedness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(4), 419–435.

Rettner, R. (2010). To buy happiness, book a plane ticket. Retrieved from http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/35729524/ns/health-behavior/t/buy-happiness-book-plane-ticket/.

Robins, R. W., Hendin, H. M., & Trzesniewski, K. H. (2001). Measuring global self-esteem: Construct validation of a single-item measure and the Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(2), 151–161.

Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Cutrona, C. E. (1980). The revised UCLA loneliness scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(3), 472–480.

Ryan, R. M. (1995). Psychological needs and the facilitation of integrative processes. Journal of Personality, 63(3), 397–427.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78.

Ryan, R. M., & Frederick, C. M. (1997). On energy, personality and health: Subjective vitality as a dynamic reflection of well-being. Journal of Personality, 65, 529–656.

Saucier, G. (1994). Mini-markers: A brief version of Goldberg’s unipolar Big-Five markers. Journal of Personality Assessment, 63, 506–516.

Sheldon, K. M. (2011). Integrating behavioral-motive and experiential-requirement perspectives on psychological needs: A two process model. Psychological Review, 118(4), 552–569.

Sheldon, K. M., Abad, N., & Hinsch, C. (2010). A two-process view of Facebook use and relatedness need-satisfaction: Disconnection drives use, and connection rewards it. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(4), 766–775.

Sheldon, K. M., & Elliot, A. J. (1999). Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well- being: The self-concordance model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(3), 482–497.

Sheldon, K. M., & Gunz, A. (2009). Psychological needs as basic motives, not just experiential requirements. Journal of Personality, 77(5), 1467–1492.

Sheldon, K. M., Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L., & Kasser, T. (2004). The independent effects of goal contents and motives on well-being: It’s both what you pursue and why you pursue it. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 475–486.

Snook, S. C., & Gorsuch, R. L. (1989). Component analysis versus common factor analysis: A Monte Carlo study. Psychological Bulletin, 106(1), 148–154.

Steiger, J. H. (1990). Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 25(2), 173–180.

Streiner, D., & Norman, C. (1995). Health measurement scales: A practical guide to their development and use (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., Blais, M. R., Briere, N. M., Senecal, C., & Vallieres, E. F. (1992). The academic motivation scale: A measure of intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivation in education. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 52, 1003–1017.

Van Boven, L., Campbell, M. C., & Gilovich, T. (2010). Stigmatizing materialism: On stereotypes and impressions of materialistic and experiential pursuits. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(4), 551–563.

Van Boven, L., & Gilovich, T. (2003). To do or to have? That is the question. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(6), 1193–1202.

Vansteenkiste, M., Niemiec, C., & Soenens, B. (2010). The development of the five mini-theories of self-determination theory: An historical overview, emerging trends, and future directions. In T. Urdan & S. Karabenick (Eds.), Advances in motivation and achievement, vol. 16: The decade ahead (pp. 105–166). UK: Emerald Publishing.

White, R. (1963). Ego and reality in psychoanalytic theory. Psychological issues series, Monograph No. 11. New York: International Universities Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Motivation for Experiential Buying Scale (MEBS)

Appendix: Motivation for Experiential Buying Scale (MEBS)

There are many ways in which people can choose to utilize their money to make themselves happier. One such way is by acquiring life experiences—an event or series of events that you personally encounter or live through (e.g., eating out, going to a concert, traveling, etc.). When using money in this way, you do not acquire a physical, tangible object that remains in your possession. Instead, you obtain only a memory of the experience or the event. This is known as an experiential purchase.

We want you to think about the reasons you typically make experiential purchases. Please indicate to what extent you agree with each of the following items as the reasons you make experiential purchases.

One of the reasons I typically spend money on life experiences is…

-

1.

They are part of how I have chosen to live my life

-

2.

They are an integral part of my life

-

3.

Because life experiences represent the kind of person I am

-

4.

Because I find life experiences stimulating

-

5.

They are in line with things I value in life

-

6.

Because I value buying life experiences

-

7.

Because life experiences improve the quality of my life

-

8.

Because I enjoy the satisfaction of being immersed in the experiences

-

9.

For the pleasure I feel during the life experience

-

10.

Because it is important to buy life experiences

-

11.

For the recognition I’ll get from others

-

12.

Because life experiences allow me to be well regarded by people I know

-

13.

For the chance to discover what others think of me

-

14.

To avoid others thinking negative thoughts about me

-

15.

Because people around me think it is really important to buy life experiences

-

16.

To impress other people

-

17.

I don’t know if I really had any good reason to buy life experiences

-

18.

I don’t really know

-

19.

Never thought about why; hard to say

-

20.

I just buy life experiences without any reason

Participants responded to items on a scale from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree).

Autonomous Motivation: sum 1–10; Controlled Motivation: sum 11–16; Amotivation: sum 17–20. To compute the short version: items 2, 7, and 8 are autonomous motivation, items 11, 13 and 16 are controlled motivation, and items 21, 23, and 24 are Amotivation.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, J.W., Howell, R.T. & Caprariello, P.A. Buying Life Experiences for the “Right” Reasons: A Validation of the Motivations for Experiential Buying Scale. J Happiness Stud 14, 817–842 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9357-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9357-z