Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has created a sense of threat, and stress that has surged globally at an alarming pace. University students were confronted with new challenges. This study examined university students’ functional difficulties and concerns during COVID-19 pandemic in two countries: Israel and Ukraine. Additionally, it examined the similarities and differences in prediction of COVID-related concerns in both countries. Two large samples of university students were drawn from both countries. Results showed that students’ main functional difficulties in both countries were: worries about their family health status and their learning assignments. In both countries, COVID-related functional difficulties and stress associated with exposure to the media added a significant amount of the explained variance of COVID-related concerns after controlling for background variables. In conclusion—while the level of exposure and difficulties may differ by country and context, their associations with students’ concerns seem robust. Additionally, repeated exposure to media coverage about a community threat can lead to increased anxiety.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has created a sense of threat, uncertainty, and stress that has surged globally at an alarming pace. It has invaded many domains of daily life and abruptly changed the routine behaviors of individuals and communities. The most frequent word to be associated with the COVID-19 outbreak in both professional literature and media coverage is “unprecedented” (appearing as of June 10 in more than 2.5 million results in a Google search), highlighting the lack of existing scripts for coping with the new reality.

A few weeks into the COVID-19 crisis, a growing number of publications had already appeared on the adverse mental health effect, mostly in terms of depression and anxiety. Płomecka et al. [1] documented the prevalence of psychological symptoms related to the COVID-19 pandemic among more than 13,000 individuals from 12 countries and five WHO regions worldwide (from March 29 to April 14, 2020). The study identified as notable risk factors: having female gender, a pre-existing psychiatric condition, or prior exposure to trauma, whereas optimism, the ability to share concerns with family and friends, having positive predictions about COVID-19, and daily exercise predicted fewer psychological symptoms. Other research emphasized the psychological consequences of quarantine [2, 3], the psychological burden on the health-care workforce [4], and the specific psychological consequences on adolescents [5]. In terms of policy, a large group of 25 mental health and trauma experts published a call for multidisciplinary research priorities for the psychological and social aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic [6].

University students are not usually considered among the most vulnerable groups that should be prioritized for early mental health interventions. However, the new reality of the rapid, global surging of COVID-19 confronted the cohort of university students with many new challenges. The abrupt disruption of everyday life and routines, the frequent loss of income and temporary unemployment, the need to change housing arrangements or return to living with their families, the loss of social connections, the new concerns about the health of their parents and extended family, and in addition, the urgent need to adapt to distance learning, created the potential for a unique combination of accumulated stress and difficulties in functioning that should therefore be studied [7]. Differences and similarities among countries in how individuals cope with COVID and what are the protective factors are relevant for understanding the consequences of the events, as well as for implementing policy in the fight against COVID-19 [6]. The current study addressed university students’ level of exposure to COVID-19, including being in quarantine and knowing people and family members who were sick, levels of exposure to media coverage of COVID and stress associated with the level of exposure to media, functional difficulties, and COVID-related concerns in two countries: Israel and Ukraine. These countries differ in many aspects as will be further discussed. Yet students may share similar functional difficulties and concern or the same risks and protective factors for increased concerns.

Level of exposure to COVID-19, including being in quarantine, is a potential source of stress [8] and therefore was addressed in this study. Another source of potential stress is exposure to media coverage of the pandemic. Unlike prior virus threats, such as SARS, Ebola, and MERS, which were perceived as localized and contained epidemics, the current COVID outbreak is more vividly present in abundant and continual worldwide media coverage. In parallel, the continual flow of information is kept pouring through various apps and social media networks. Garfin et al. [9] argued that the public health consequences of the novel COVID outbreak are amplified by media exposure. Indeed, in China, Gao et al. [10] reported on the positive association of mental health problems, especially depression and anxiety, with frequent social media exposure among the general population during the COVID-19 outbreak. Thus, level of exposure to COVID-19 media coverage, especially among young people who are connected to immediate notifications with alarming statistics, may be experienced as stressful and consequently may be associated with increased distress or impaired coping.

The unprecedented aspects of the COVID-19 crisis call indeed for re-thinking or re-calculating innovative approaches not just to inform the development of novel prevention and interventions [11], but also for conceptualizing and measuring its consequences [12]. Therefore, rather than focusing on mental health distress and symptoms of depression and anxiety, which are measured in a general way, the students’ survey in the present study focused on constructing specific tools (or tailor-made instruments) for the assessment of functional difficulties and concerns within the specific COVID-related context. By using the term “concerns,” we encompassed a variety of worries, in different domains, that were relevant to the impact of the COVID-19 crisis. These concerns can be conceptualized somewhat differently from “objective fears” and “subjective anxiety,” and under the unique circumstances of the COVID threat might be a combination of the objective and subjective domains. Therefore, this study examined COVID-related functional difficulties, which were the immediate, associated difficulties in daily functioning (e.g., loneliness, boredom, and major functional difficulties in academic learning); and then examined their relationships with various COVID-related concerns; for example, concerns regarding various aspects of uncertainty intertwined in the new pandemic.

Using a cross-national lens can shed light on the relative importance of the specific risk factors that play a role in this specific global crisis. Israel and Ukraine each have a long history of trauma and moreover have faced continual traumatic stress for prolonged periods of time [13, 14]. Yet aside from their vast cultural differences, they are currently facing a common global threat in COVID-19. The COVID outbreak confronted these two countries with the backdrop of different systems of medical care, different levels of media exposure and trust in the health-care authorities, and with different levels of accessible resources. The numbers of infected and deceased people in the two countries, according to John Hopkins sources (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.htm) for June 10, 2020, were 18,268 infected people and 299 deaths, and a ratio of 34.3 deaths per million citizens in Israel; and 28,381 infected people and 833 deaths, and a ratio of 19.7 deaths per million citizens in Ukraine. However, these statistics reflect only part of the experienced phenomena in each of the countries, since media coverage played a very different role in each of the countries. In Israel, a policy of monitoring, lockdown, and increased testing was implemented very early in the process, and in addition, very detailed information about the first infected people was provided in the public media in order to alert all potential contacts to enter an immediate quarantine lasting 14 days. In Ukraine, no such policy and early measures were taken. At the beginning of 2020, COVID-19 was reported by the Ukrainian media as a threat that was happening far away, and mostly as a foreign news topic. However, in March and April, the Ukrainian media revealed the lack of an adequate testing system for detecting the disease and isolating any infected individuals. Therefore, the statistics for infected population and mortality in Ukraine were much lower than in other countries where the monitoring was very high.

This cross-national research study aimed at presenting and comparing the level of University students COVID-related exposure, the level of exposure to media coverage of the COVID pandemic and the stress associated with exposure to the media, the main COVID-related functional difficulties, and the COVID-related concerns among university students. Additionally, we examined the similarities and differences in prediction of COVID-related concerns in both countries, after adjusting for background variables. Students have been shown to generally perceive themselves as a healthy group [15]. Studies on COVID have shown that young age and good health status prior to COVID are protective factors for COVID mortality and complications [16, 17]. This evidence may be related to their potentially experiencing fewer concerns. Female gender was associated with higher level of symptoms in COVID-19 studies [2, 3]. We therefore adjusted for gender, age, and perceived health status in the multivariate analyses.

Method

Research Population and Sample

Israel

The Israeli population included all students (ages 18+) of one of the research Universities in Israel: more than 20,000 students, who learn in 14 different faculties. We approached all students via an e-mail from the Office of the Dean of Students. Of the total, 4658 (21%) responded to the questionnaire. However, 502 students did not respond to any background variables, and were therefore removed from the analyses. The final sample included 4156 students (19% response rate). The sample included 66% females, an average age of 27.52, (SD = 6.21), and 15.4% who were parents. In addition, 68.2% were undergraduates, with 53% studying in the humanities or the social sciences faculties.

Ukraine

The Ukrainian population included participants from a University in West Ukraine, with 14,105 students from 14 colleges and faculties. It is located in the Volyn Oblast, estimated to have the highest number of combat fatalities in the war in the Eastern Ukraine, and internally displaced persons after the Chernobyl disaster. We approached all students through the Students’ Union Office; 656 students responded. However, 102 students did not respond with any background variables and did not complete the questionnaire. They were therefore removed from the analyses. The final sample included 554 students; 67.4% females, an average age of 20.93, (SD = 3.29), and 3.2% who were parents. In addition, 74.0% were undergraduates, while 88.4% were studying in the humanities or the social sciences faculties.

Measurements

In order to ensure the questions were relevant to the new phenomena of COVID-19, measurement tools were tailored specifically for this study. The scales were first developed in the Hebrew language and then were translated into English. The English translation, which was also tested for language and translation accuracy by three English native-speaking experts who are fluent in Hebrew, was translated into Ukrainian and back-translated into English.

Independent Variables

Exposure to COVID-19

Three questions were asked: “Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, were you in isolation due to infection or suspected infection?” “Do you personally know anyone who was tested positive for COVID-29?”; and “Has anyone from your family or close friends been tested positive for COVID-19?” A composite score of exposure to COVID was created by averaging the three items.

Exposure to Media Coverage of COVID

One question was asked: “Do you actively search for information about the progress of the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., read news websites, use apps that are continually updated, listen to radio/TV, etc.) to learn about new developments?” Responses were: 1. “never or almost never,” 2. “a few times a day,” and 3. “all the time.”

Stress Associated with Exposure to the Media

One item was asked: “To what extent is the information you hear in the news calming vs. stressful?” Responses were provided on a 10-item scale ranging from 1. “Very stressful” to 10. “Very calming.”

COVID-Related Functional Difficulties

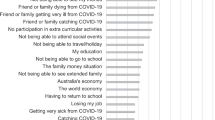

Seven items were asked, introduced by a statement: “These days, to what extent do you experience difficulty in the following situations? Items and their distributions are presented in Table 1. Inter-item reliability (α Cronbach) was reasonable (α Cronbach = 0.67 and 0.70 in the Israeli and Ukrainian samples respectively). A composite score of COVID-related functional difficulties was constructed by averaging all seven items.

Dependent Variable

Students’ COVID-Related Concerns

Seven questions were asked, beginning with the statement: “To what extent are you concerned about each of the following things regarding COVID…”. Items and their distributions are presented in Table 2. Inter-item reliability (α Cronbach) was high and similar in both countries (0.84 and 0.83 in the Israeli and Ukrainian samples respectively). We constructed a composite scale, averaging all seven items.

Background variables of gender, age, country, and 1-item “perceived health status” [18] were included as control variables.

Study Design

A cross-sectional survey.

Data Collection and Ethical Consideration

Ethic approval was provided by the Hebrew University, School of Social Work Ethic Committee and by the University in West Ukraine ethic committee. Following ethical approval, we constructed the questionnaire with the Qualtrics program, and delivered it as a link to all students in both universities. The dean’s office distributed the questionnaire link to all students via their institutional e-mail addresses. Three reminders were sent. The questionnaire was anonymous. An informed consent was presented first, and only students who marked “agree” were referred to the questionnaire. Data collection in Israel took place in the midst of the pandemic, March 23–April 26, 2020. During most of that time there were guidelines instructing citizens to “stay at home,” and for a few days during the Jewish holidays, there was even a curfew.

In Ukraine, data collection took place from March 29 to April 17, 2020.

Data Analysis

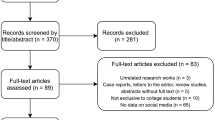

Descriptive analyses were conducted first, following by comparisons between countries for the level of each variable included in the study, through the Independent t-test. Multiple hierarchical regressions for the dependent measure were conducted. We also examined the potential interaction effect between country and each of the predictors of COVD-related concerns included in the regression equation, using the PROCESS macro for SPSS [19].

Results

Israeli students reported larger exposure to COVID than Ukrainian students: 10.7% of the Israeli students versus 1.2% of the Ukrainian students were in quarantine due to suspected or actual COVID infection (χ2(2) = 55.63, p < .001). Higher rates of Israeli students also reported knowing at least one person who tested positive for COVID-19 (23.6% versus 6.4% among Israeli and Ukrainian students respectively; χ2(2) = 87.28, p < .001). Students generally reported good health status. Ninety percent of the Israeli students and 74.9% of the Ukrainian students reported “good” or “very good” physical health. Table 1 presents the distribution and means (and SD) of COVID-related functional difficulties. It shows that students from both countries indicated their main difficulty was worrying about their family health status, followed by “dealing with learning assignments.”

Table 2 presents the distribution and means (and SD) of students’ concerns. The means of each item showed that the Israeli students’ major concern was “the fact that it is not clear when the state of emergency will end,” followed by “the quick spreading of the virus around the world” and “the restriction on daily life due to COVID.” For Ukrainian students the main concern was “the fact that there is no vaccination for the virus,” followed by “the quick spreading of the virus around the world” and “it is not clear when the state of emergency will end.”

Table 3 presents the level of each of the study’s variables among students from both countries and reports significant differences that were found in the Independent sample t-tests. “Degrees of freedom” varies as a function of the confirmation of an equal variance assumption based on Levene’s test. It shows that while Ukrainian students reported worse perceived health status than Israeli students (t(654.87) = 12.06, p < .001), Israeli students reported a higher level of COVID-related concerns (t(4,726) = 10.67, p < .001), higher exposure to media coverage of COVID (t(738.99) = 2.92, p < .01), and greater stress associated with exposure to the media (t(4,709) = 27.93, p < .001). Students in both countries showed a similar level of COVID-related functional difficulties (t(680.62) = 0.13, p = .91).

Table 4 presents separate hierarchical regression analyses for COVID-related concerns for Israeli and Ukrainian students. It shows that female gender was related to greater COVID-related concerns in both samples (β = .21, p < .001 and β = .09, p < .05 for Israeli and Ukrainian samples respectively). Better perceived health status was also associated with a lower level of concern (β = − .22, p < .001 and β = − .10 for Israeli and Ukrainian samples respectively, p < .05). Overall, these background (control) variables explained 10% and 2% of the variance among Israeli and Ukrainian students, respectively.

While direct exposure to COVID-19 was not significantly associated with COVID-related concerns, exposure to media coverage of the COVID-19 crisis was significantly associated with COVID-related concerns in the two countries (β = .27, p < .001 and β = .21, p < .001 for Israeli and Ukrainian samples respectively). COVID-related functional difficulties and the stress associated with exposure to the media were included in the third step and added a significant amount to the explained variance (24% and 15% among Israeli and Ukrainian students respectively). COVID-related functional difficulties were significantly and positively associated with COVID-related concerns: the greater the functional difficulties, the higher their concerns (β = .34, p < .001 and β = .25, p < .001 for Israel and Ukraine samples respectively). The level of stress associated with exposure to the media showed opposite directions in the two samples, as discussed below. The complete model explained 41% and 22% of the variance among Israeli and Ukrainian students respectively.

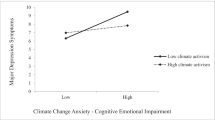

Potential differences between the two countries in the strengths of the associations between each of the predictors and COVID-related concerns were tested as interactions effect, using the PROCESS macro for SPSS [19]. Each potential interaction effect was tested separately, while all the other seven variables were entered into the regressions analyses as covariates. The analyses revealed only one significant interaction effect (p < .001), which explained .027 of COVID-related concerns variance over and above the main effects and the control variables; while stress associated with exposure to media was positively associated with COVID-related concerns (the greater the stress, the higher the concerns; B = 0.13, SE[B] = 0.006, p < .0001) among Israeli students, it was negatively associated with COVID-related concerns among Ukrainian students (B = − 0.09, SE[B] = 0.015, p < .0001).

Discussion

The COVID-19 outbreak introduced new stressors and concerns for university students, including concerns about the uncertainty surrounding the fast surging of the disease [3]. This study is a preliminary effort to examine student COVID-related concerns and whether level of exposure to COVID, exposure to media-coverage, stress associated with the media exposure, and functional difficulties are related to COVID-19 related concerns.

Our findings showed that students were concerned mainly with the uncertainty of when the pandemic will end, the fact that a vaccine was not yet available and not expected to be available in the near future, and the wide spread of the virus around the world. Ukrainian students reported a lower level of COVID-related concerns than their Israeli counterparts. This finding can be interpreted in several ways. First, testing for COVID-19 was extremely limited in Ukraine due to the lack of tests, especially at the beginning of lockdown in the country. Therefore, due to insufficient testing, the statistics in Ukraine were more “favorable” than in other countries, which might have decreased students’ concerns aligned with COVID-19. Another potential interpretation for lower COVID-related concerns among Ukrainian students is that they are experiencing many other, perhaps more severe concerns, such as temporary unemployment, limited mobility, and social isolation during the COVID outbreak. These interpretations should be investigated further in future studies.

The study’s findings showed that students from both countries expressed common core difficulties: worrying about their family health status, followed by dealing with learning assignments and online learning. The students’ worries for their family health may reflect a perceived responsibility to watch and monitor the health of family members, an interpretation supported by a recent commentary indicating that among COVID-related fears is concern for significant others, especially attachment figures such as parents and intimate partners [20]. This fear represents a reversal of the more usual situation [20]: instead of being protected by attachment figures and in turn protecting them, students experience themselves as potentially dangerous to those they love and responsible for their health. The high level of fear among Ukrainian students for their families’ health may indicate that they relied on their families for caring and support [21], and reflect the lack of qualified psychosocial support for university students, which also emphasizes the important role of the family in the pandemic. Students reported only mild fear for their own health. This finding may be explained by their perceived good health and the cumulative evidence that young age is a protective factor for COVID-19 complications and deaths [17]. Nonetheless, Ukrainian students reported worse health status than their Israeli counterparts. This finding supports previous results identifying a health crisis in Ukraine aligned with decreasing life expectancy, and a low quality of health care [22, 23].

Students’ academic and online learning difficulties can be explained by the rupture in their routine tasks and surroundings as students and are also in accord with previous literature revealing challenges in online learning [24, 25].

Students reported high stress associated with exposure to the media coverage of COVID-19. This finding is in accord with previous studies showing that heightened exposure to media coverage of crises and disasters is associated with increased stress reactions, worries, and impaired functioning, and may have downstream effects on health [9]. Ukrainian students reported lower stress associated with exposure to media than Israeli students. This can be explained by the limited access of Ukrainian students to real COVID-19 statistics. Alarming information and statistics were presented mostly about countries other than Ukraine. Thus, information on COVID spread in other countries was probably not perceived by the students as a personal threat to their own or their family’s health and was therefore not so stressful.

Results of the regression analysis emphasize the relationships between COVID-19 functional difficulties and COVID-19 concerns. Specifically, after controlling for background variables and level of exposure, COVID-19 functional difficulties were highly related to COVID concerns and explained a significant amount of their variance. Furthermore, these associations were similar in the two countries. Our findings are in accord with a previous study conducted during a more routine time before COVID [26], and a commentary related to COVID-19 [27] indicating that, at least among students, disruption of their daily routine and the closing of the academic institutes are associated with fears and concerns [27]. Thus, the vast interruption to daily routine caused by the COVID-19 outbreak, as well as the new perceived duty of protecting their family members from being infected, may take a heavy toll on students’ mental health.

One unanticipated finding of regression analysis, however, was that while stress associated with exposure to the media was positively associated with greater concerns for Israeli students, as would have been expected, it was associated with lower concerns among Ukrainian students. This can be explained in line with the previous findings regarding low stress levels associated with exposure to the media among Ukrainian students. If stress associated with exposure to the media was low due to general concern about occurrences in the world but not in Ukraine, then students might not have been engaged in COVID-related concerns, while being stressed by the media, as this was “others’ problems,” not their own, and such a perception might be even comforting. This interpretation should be further studied.

Study Limitations and Future Directions

This study had several limitations that should be addressed. First, it relied on a cross-sectional survey and therefore cannot make an argument regarding causality. Second, it was conducted during the peak of the pandemic and therefore did not show potential long-term consequences. A longitudinal study could show whether the concerns fade or worsen over time. Finally, this study did not include potential protective factors, such as better housing conditions, online counseling services, and high support from the university. Such potential protective factors and others should be addressed in future studies.

Conclusions

We join the initiative of mental health experts in pointing out that insights from the social and behavioral sciences need to guide the recommendations of epidemiologists, public health experts, policy makers, and community leaders [28]. Additionally, we support the urgent call of professionals from the trauma field [12] to develop novel approaches for diagnosis, prevention, and public outreach and communications for future global health crises like the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, for university students there is a need to develop and adapt counseling services geared to addressing both the potential learning difficulties and the emotional distress that may emerge in times of stress and trauma. A related concern is that media coverage of global health crises can have unintended consequences for those at relatively low risk for direct exposure to the disease, leading to potentially severe public health repercussions [9]. Thus, there is a need to warn of the risk that repeated exposure to media coverage about the community threat can lead to increased anxiety and stress responses, which in turn can impact health and help-seeking behaviors [9].

References

Płomecka, M., Jawaid, A., Radziński, P., & Baranczuk, Z. (2020). Mental health impact of COVID-19: A global study of risk and resilience factors. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/zj6b4.

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., et al. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395(10227), 912–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8.

McGinty, E. E., Presskreischer, R., Han, H., & Barry, C. L. (2020). Psychological distress and loneliness reported by US adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.9740.

Adams, J. G., & Walls, R. M. (2020). Supporting the health care workforce during the COVID-19 global epidemic. JAMA, 323(15), 1439–1440. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.3972.

Oosterhoff, B. (2020). Psychological correlates of news monitoring, social distancing, disinfecting, and hoarding behaviors among US adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/rpcy4.

Holmes, E. A., O'Connor, R. C., Perry, V. H., Tracey, I., Wessely, S., Arseneault, L., et al. (2020). Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(6), 547–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1.

Khan-Burki, T. (2020). COVID-19: Consequences for higher education. Lancet: Oncology, 21(6), P758. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30287-4.

Kim, H.-C., Yoo, S.-Y., Lee, B.-H., Lee, S. H., & Shin, H.-S. (2018). Psychiatric findings in suspected and confirmed middle east respiratory syndrome patients quarantined in hospital: A retrospective chart analysis. Psychiatry Investigation, 15(4), 355–360. https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2017.10.25.1.

Garfin, D. R., Silver, R. C., & Holman, E. A. (2020). The novel coronavirus (COVID-2019) outbreak: Amplification of public health consequences by media exposure. Health Psychology, 39(5), 355–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000875.

Gao, J., Zheng, P., Jia, Y., Chen, H., Mao, Y., Chen, S., et al. (2020). Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE, 15(4), e0231924. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231924.

Wang, C., Pan, R., Wan, X., Tan, Y., Xu, L., Ho, C. S., et al. (2020). Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), 1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051729.

Horesh, D., & Brown, A. D. (2020). Traumatic stress in the age of COVID-19: A call to close critical gaps and adapt to new realities. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(4), 331–335. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000592.

Doty, S. B., Haroz, E. E., Singh, N. S., Bogdanov, S., Bass, J. K., Murray, L. K., et al. (2018). Adaptation and testing of an assessment for mental health and alcohol use problems among conflict-affected adults in Ukraine. Conflict and Health, 12(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-018-0169-6.

Pat-Horenczyk, R., & Schiff, M. (2019). Continuous traumatic stress and the life cycle: Exposure to repeated political violence in Israel. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(8), 71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-1060-x.

Prokhorov, A. V., Warneke, C., de Moor, C., Emmons, K. M., Jones, M. M., Rosenblum, C., et al. (2003). Self-reported health status, health vulnerability, and smoking behavior in college students: Implications for intervention. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 5(4), 545–552. https://doi.org/10.1080/1462220031000118649.

Dowd, J. B., Andriano, L., Brazel, D. M., Rotondi, V., Block, P., Ding, X., et al. (2020). Demographic science aids in understanding the spread and fatality rates of COVID-19. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(18), 9696. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2004911117.

Jordan, R. E., Adab, P., & Cheng, K. K. (2020). Covid-19: Risk factors for severe disease and death. BMJ, 368, m1198. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1198.

DeSalvo, K. B., Bloser, N., Reynolds, K., He, J., & Muntner, P. (2006). Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21(3), 267–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00291.x.

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford publications.

Schimmenti, A., Billieux, J., & Starcevic, V. (2020). The four horsemen of fear: An integrated model of understanding fear experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 17(2), 41–45.

Yablonska, T., & Melnychuk, T. (2017). Psychological support for families during crises (as exemplified by families members of Ukrainian war veterans). Current Problems of Psychiatry, 18(2), 87–94.

Luck, J., Peabody, J. W., DeMaria, L. M., Alvarado, C. S., & Menon, R. (2014). Patient and provider perspectives on quality and health system effectiveness in a transition economy: Evidence from Ukraine. Social Science & Medicine, 114, 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.05.034.

Peabody, J. W., Luck, J., DeMaria, L., & Menon, R. (2014). Quality of care and health status in Ukraine. BMC Health Services Research, 14(1), 446. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-446.

Kearns, L. R. (2012). Student assessment in online learning: Challenges and effective practices. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 8(3), 198.

Tanyel, F., & Griffin, J. (2014). A ten-year comparison of outcomes and persistence rates in online versus face-to-face courses. B> Quest, 1, 22.

Agnew, M., Poole, H., & Khan, A. (2019). Fall break fallout: Exploring student perceptions of the impact of an autumn break on stress. Student Success. https://doi.org/10.5204/ssj.v10i3.1412.

Zhai, Y., & Du, X. (2020). Addressing collegiate mental health amid COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Research, 288, 113003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113003.

Van Bavel, J. J., Baicker, K., Boggio, P. S., Capraro, V., Cichocka, A., Cikara, M., et al. (2020). Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nature Human Behaviour, 4, 460–471.

Funding

No Funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schiff, M., Zasiekina, L., Pat-Horenczyk, R. et al. COVID-Related Functional Difficulties and Concerns Among University Students During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Binational Perspective. J Community Health 46, 667–675 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-020-00930-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-020-00930-9