Abstract

I study the relationship between land concentration and the expansion of state education in 19C England. Using a broad range of education measures for 40 counties and 1,387 School Boards, I show a negative association between land concentration and local taxation, school expenditure, and human capital. I estimate reduced-form effects of 19C land concentration, geographic factor endowments, and the land redistribution after the Norman conquest of 1066. The negative effects on state-education supply are stronger where rural labour can easily migrate, where landowners had political power, is not offset by voluntary schooling, and not driven by a demand channel. This suggests that landowners opposed taxation in order to reduce state education provision.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Inequality can be harmful for economic growth (Galor and Zeira 1993). One reason is that growth-promoting institutions, such as state education, may be difficult to implement where wealth is concentrated in the hands of a small elite (Galor and Moav 2006). Galor et al. (2009) formalize a negative relationship between state education and land concentrated in the hands of a small group of landowners. This relationship is explained by landowners influencing the political process in order to prevent the expansion of education and, hence, to reduce the mobility of the rural labour force.

This paper investigates the relationship between land concentration and education provision in England. I show that the expansion of state education in the late 19C is strongly negatively associated to two deep-rooted factors which laid the groundwork for inequality: geographical factor endowments and the Norman conquest of 1066, a historical event that massively redistributed landownership. I document empirically the sheer persistence of land inequality from 1066 to 1870, and examine the contemporaneous effect of land concentration on state education and the mechanisms behind it. My results support Galor et al. (2009)’s proposed mechanism: the opposition of great landowners to state education provision through the political process.

To study these questions, I focus on the 1870 Education Act. Prior to 1870, elementary schooling was provided by religious societies, who established and ran voluntary schools funded by non-tax donations, school fees, and government subsidies. The 1870 Education Act sought to expand elementary schooling to the entire school-aged population. To do so, it introduced new, state-run, non-denominational board schools funded by local taxation (henceforth board schools).Footnote 1 Between 1870 and 1902, ca. 5,700 board schools for 2.6 million children were created. This setting offers a number of advantages. First, the expansion of education was decentralized: in each education district, a School Board taxed local residents through a tax on property (e.g., land) to fund the building and expenditures of board schools. Historical evidence suggests that large landowners opposed local taxes for education and that, in some areas, they took over School Boards by placing individuals favourable to their interests in the Boards (Stephens 1998). The local nature of education provision allows me to examine the relation between land concentration and the expansion of education at a highly disaggregated local level.

Second, my data on education provision is very rich. I digitize a source that, to the extent of my knowledge, remains unexplored by economists: the reports of the Committee of Council on Education. These reports provide yearly data on the taxes set by 1,387 local School Boards in 1873–78 and on 22 different education measures for 40 counties in 1871–99: On board schooling, I record all sources of funding and expenditures. On board and voluntary schooling, I record the number of schools, teachers hired and expenditures on their salaries, pupils enrolled and attending, and measures of human capital accumulation in arithmetics, reading, and writing. This rich data allows me to disentangle the mechanisms behind the relationship between land concentration and education to which the existing literature—mostly restricted to literacy and enrolment rates—remains silent.

My first contribution is to evaluate the relationship between education provision and two deep-rooted determinants of land concentration: one historical, another geographical. The historical determinant is the Norman conquest of 1066. Before 1066, England was a mosaic of landowners. After the conquest, more than half of the land was given to 190 Norman nobles, laying the groundwork for future land inequality. The main geographical determinant of land concentration is soil texture, a factor deemed important for land concentration in England (Clark and Gray 2014).Footnote 2 In addition, I consider a broad set of geographic and climatic covariates which, in Engerman and Sokoloff (2000)’s framework, may also be important determinants of land concentration and later education provision: terrain ruggedness, suitability for each of the main crops grown in England, temperature, precipitation, distance to rivers and to the coast.

I document a strong reduced-form effect of land concentration in 1086 on all my education measures. Using digitized data from the Domesday book, I construct measures of land concentration in 1086 in the areas around each School Board and at the county level. I show that local taxes for education, aggregate board and voluntary schooling expenditures, and human capital accumulation were lower where the largest Norman landowners received more lands. The geographic determinants of land concentration are also associated with education provision, but the relationship is weaker.

I show that these reduced-form effects are likely driven by a strong persistence of land inequality from 1086 to 1870. I construct measures of land concentration in 1870 from Bateman (1883) and show that the estates of 19C great landowners (i.e., peers with 2,000 acres or more) emerged where land was given in a more concentrated manner in 1086.Footnote 3 I discuss institutional arrangements that contributed to this persistence by restricting access to land, and rule out alternative persistence channels empirically. Specifically, I show that local differences in land concentration in 1086 are not associated to pre-conquest economic development—proxied by the density of Roman roads—nor to a range of economic and religious county characteristics in the 1871 Census.Footnote 4

My second contribution is to examine the contemporaneous relationship between education provision and land concentration, as well as the mechanisms behind it. After controlling for local geographic, climate, and population characteristics, I find that School Boards located near the 19C great landowners set lower taxes to fund the expansion of education. The estimated effects are quantitatively important: Increasing land concentration by one standard deviation is associated with a reduction in tax rates by 8%. I also exploit cross-county variation to examine the relationship between landownership and a wider range of education measures. I find that in counties where land was more concentrated School Boards raised fewer funds from taxes, and that funds from other sources (e.g., Parliament grants) did not compensate. Less money was invested per child in board schools. Aggregate measures of board and voluntary schooling are also negatively associated with land concentration: overall, fewer teachers and class assistants were employed and expenditures on their salaries were lower. This suggests that voluntary schooling could not fully compensate the under-provision of board schools. This had important consequences on human capital accumulation: children were less likely to pass the reading, writing, and arithmetics’ national exams.

Although these reduced-form effects are based on the predictions of well-founded theoretical models, I avoid causal language in their interpretation. I gain insights into identification from an IV-estimation using the two deep-rooted determinants of land inequality as instruments for land concentration in 1870.

Finally, I examine the contemporaneous mechanisms through which land concentration affected education provision. Land concentration can affect the expansion of education through a supply or a demand mechanism. The former emphasizes the landowner’s economic incentives to oppose education provision through the political process (Galor et al. 2009). The latter, the individuals’ underinvestment in human capital in areas where land is concentrated (Cinnirella and Hornung 2016; Ashraf et al. 2017). Another mechanism through which landowners may affect education provision is by favouring voluntary vs. board schooling. Finally, the relation may also be affected by smaller landowners (Tollnek and Baten 2017). These different mechanisms have critically different implications for economic growth and to evaluate available policy instruments, e.g., land reform or public delivery systems. But disentangling these mechanisms is difficult. The reason is that in most settings the available data is limited to enrolment or literacy rates—measures related both to education supply and demand—and does not distinguish different types of schooling. My rich dataset allows me to overcome these issues.

On the supply mechanism, the evidence supports Galor et al. (2009)’s mechanism. Because of the lack of complementarity between human capital and land, the expansion of education is associated with a loss of rural labour force which landowners try to prevent. Consistently, I find stronger, more negative effects of land concentration on School Board activity near large towns which could attract rural labour force. Next, I use School Board taxes to show that the great landowners’ opposition to taxation was stronger where they held local political power. I code the biographies of 369 great landowners and record their appointments to political offices that reflect local power. I find that the effect of land concentration on local taxes is 1.6% stronger for School Boards ten miles closer to a great landowner who held important local offices (e.g., Lord Lieutenant) or who was elected Member of Parliament. This differential effect is entirely driven by Conservative great landowners. This lends credence to the hypothesis that landowners opposed the expansion of education through the political process.

On the board vs. voluntary schooling mechanism, I use the number of board and voluntary schools in each county, as well as aggregate expenditures in all schools. The evidence suggests that great landowners’ supported voluntary schooling, but this support did not offset the negative impact on School Board activity. This likely reflects the fact that voluntary schooling partly relied on non-tax charitable donations, which are subject to externalities and market failures similar to those in private schooling provision (Galor and Zeira 1993).

On the demand mechanism, I use a supply-side instrument to correct for the fact that enrolment and attendance can be affected by supply factors. The instrument is the Fee Grant Act (1891), which increased school funds nationally in order to eliminate school fees. I use this supply-side instrument to estimate the demand for education—that is, the intercept and the slope of the relationship between enrolment (or attendance) and school fees. The estimated demand schedules are almost identical in counties with low and high land inequality. That is, where land was concentrated the demand for education was not lacking.

On the role of smaller landowners, I show that yeomen had positive effects on education provision, yet these did not offset the impact of great landowners.

Relative to the existing literature, I make the following contributions. First, previous work has documented a negative effect of inequality on education in the Americas.Footnote 5 For industrial economies, the evidence in favor of the hypothesis of a negative relation appears overwhelming, in the time period in which industrial demand for human capital is significant. Galor et al. (2009), Vollrath (2009), and Ramcharan (2010) show that land inequality distorted education provision in the United States during the Second Industrial Revolution. Cinnirella and Hornung (2016) find a similar relationship in 19C Prussia, driven by a demand mechanism. Baten and Hippe (2018) confirm a negative relationship between land inequality and numeracy in a large sample of European regions, and show that this relationship is altered in industrial economies.Footnote 6 My paper is the first to show that land concentration distorted state education in England. Since England was the cradle of the Industrial Revolution, this result has implications for unified growth theories that emphasize the role of human capital for technological progress and the demographic transition (Galor and Weil 2000; Galor and Moav 2002). Specifically, my findings support (1) that land–human capital complementarity can affect education supply, (2) that land concentration is important for the changes initiated after the Industrial Revolution, and (3) that the structural relationship between landownership and the expansion of education had not broken before the Second Industrial Revolution (1870–1914). This is in line with Galor et al. (2009)’s prediction that the balance of power between landed and industrial elites is crucial for education reforms. It is also consistent with the fact that he landed aristocracy retained substantial local political power in the late-19C (Allen 2009).

My second contribution is to bring together two literatures studying the relation between inequality and education: one that emphasizes contemporary mechanisms;Footnote 7 another that emphasizes its deep roots (Engerman and Sokoloff 2000). Specifically, Engerman and Sokoloff (2000) suggest that in certain areas of Latin America, factor endowments favored the emergence of intensely unequal societies after colonization. There, the elite attempted to deprive masses from tools, such as voting rights and education, that could alter the political status quo and permit redistribution. I find that deep-rooted historical and geographic factors were important in England, but that history tops geography. This finding contributes to a large literature highlighting the importance of history and critical junctures for later economic outcomes, over and above unchanging geographic factors (Nunn 2014). In detail, I show that inequality originated in the Norman conquest eventually distorted a large redistributive policy in the 19C. This illustrates how deep-rooted land inequality can transform itself into regional differences in human capital, and hence, persist through periods of transformation like the Industrial Revolution. Similarly, Heldring et al. (2021) show that the dissolution of the English monasteries in 1535 redistributed land from the Church to the gentry and triggered local differences in industrialization by 1830.Footnote 8

My third contribution is to build a new dataset with several measures on board- and voluntary-education provision and human capital. This allows to me to study the different causal mechanisms proposed in the literature in a unified framework. I find that land concentration affected education provision through the political process (Galor and Moav 2006; Galor et al. 2009). This supports the idea that political inequality may be more important than economic inequality for long-run development (Acemoglu et al. 2008).Footnote 9 Voluntary schooling did not compensate this lack of provision and the masses’ demand for education was not the binding factor for the expansion of schooling in my setting.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 presents the underlying theoretical framework and the historical background. Section 3 describes the data. Section 4 examines the persistence of land concentration from 1066 to 1870. Section 5 presents estimates of the reduced-form relationship between education provision, historical land concentration, and geography. Section 6 examines the contemporaneous relationship and the mechanisms behind it. Finally, Sect. 7 concludes.

2 Theoretical and historical background

Different conceptual frameworks predict a negative relation between inequality and education provision. Engerman and Sokoloff (2000) emphasize the deep roots of this relation. They suggest that early inequality can persist over centuries through institutions that restrict land access, limit suffrage, and block education reforms aimed at the masses. Their case study considers two deep-rooted determinants of inequality: one historical (colonization), another geographic (factor endowments).Footnote 10 Hence, two predictions stem from this theory: First, a persistence of inequality over long periods. Second, a negative reduced-form relation between historical and geographical deep-rooted determinants of inequality and later education provision.

Galor et al. (2009) also predict a negative relation between land inequality and state education. For them, the relation is driven by a contemporaneous mechanism: the lack of complementarity between human capital and land. In detail, state education increases the human capital of the masses which, due to the lack of complementarity with land, boosts labour productivity and wages in industry more than in agriculture. In turn, migrating to cities becomes attractive for the rural labour force, which raises wages in agriculture. The loss of rural labour force and the rise of wages in agriculture reduces the value of land. Landowners, hence, have economic incentives to oppose state education. The theory shows that the adverse effects of state education for landowners are aggravated if landownership is concentrated. In addition, if the tax burden to fund state education falls on landowners—e.g., via a tax on land—the value of land falls further, magnifying the landowners’ losses.Footnote 11 Altogether, two predictions stem from this theory: that landownership concentration leads to lower taxation to ensure lower state education provision and that a crucial mechanism behind this relation is the landowners’ political power to effectively oppose education taxes.

Finally, the relation may be driven by a demand channel. Where inequality is high, landowners may use labour coercion to reap the returns of their workers’ private investments. As a result, rural workers may underinvest in their human capital (Cinnirella and Hornung 2016; Ashraf et al. 2017).Footnote 12 The testable prediction is that the demand for education is lower where land is more concentrated.

2.1 Education provision in late-19C England

In the Second Industrial Revolution, the demand for skilled labour increased. For example, job advertisements in the 1850s mentioned literacy as a desired characteristic (Mitch 1993, p. 292). At that time, however, England’s education system struggled to meet this demand. The illiteracy rate in 1852 was higher than in Prussia and the US, countries that had introduced a state education system at least 50 years before England (Sanderson 1995).Footnote 13

Before 1870, elementary education was provided almost exclusively by two religious societies: the Church of England’s National Society and the nonconformist British and Foreign School Society. These societies established and ran voluntary schools, which operated with “limited and indirect state support” (Sanderson 1995, p.77). From 1833, many voluntary schools (not all) received Parliament grants,Footnote 14 but 2/3 of their funds still came from non-tax donations and school fees by 1873 (see Appendix Table A2).Footnote 15 These schools enjoyed considerable autonomy. The state had no control over the curricula until 1862, when Parliament grants were conditioned on children’s reading, writing, and arithmetics’ results (‘payment by results’).Footnote 16 State supervision was often limited by the sparsity of inspectors,Footnote 17 whom bishops could veto for anglican voluntary schools (Mitch 2019, p.304). Even in cases of severe mismanagement, voluntary school governance could not be replaced (Gordon 1974, p.8). Overall, although a significant network of voluntary schools was created before 1870, there was “a clear limit to their potential expansion” (Green 1990, p.16). Hurt (1974) estimates that voluntary schooling did not reach 1 in 3 children (p.34).Footnote 18

The 1870 Education Act (Forster’s Act) aimed to expand elementary schooling to the entire school-aged population, “filling in the gaps" of the voluntary system (Mitch 2019, p.305). The main motivation was to meet the industrialists’ and trade unions’ demand for an educated workforce (McCann 1970).Footnote 19 This is illustrated by Forster’s address to the House of Commons: “Upon the speedy provision of elementary education depends our industrial prosperity” (Hurt 1971, p.223-4). That said, the Act was supported by a diverse coalition which also included liberals and non-conformists. Liberals sought to educate the men newly enfranchized in 1867 (Lawson and Silver 2013, p.308). Non-conformists supported the non-denominational board schools to undermine the anglican control of the school system through voluntary schools. The stalemate between non-conformists and anglicans was broken by the agreement to fund board schools with local taxes and, in return, increase Parliament grants to anglican voluntary schools.

The Education Act created 5,700 schools for 2.6 million children in 1870–1902 (Maclure 1968, p.152). This expansion of schooling was decentralized and funded mostly by local taxes. Specifically, School Boards were created and given the power to tax local residents with a tax on property similar to the poor rate. This tax was mostly levied on land, especially in rural areas. In addition, School Boards were eligible for Parliament grants. These grants were based on children’s grades in the national exams, which limited education to exam topics (Green 1990, p.7). All these funds were then used by School Boards to build board schools. In addition, School Boards had discretion over expenditures in board schools, could pay the school fees of poor children, and pass by-laws making attendance compulsory in their district (Stephens 1998). As explained above, the 1870 Act did not fully break with the past. The new, non-denominational board schools coexisted with voluntary schools, which were ran mostly by the Church of England, funded through non-tax donations, and continued receiving Parliament grants.

Initially, School Boards were created in municipal boroughs, parishes, and Poor Law districts where existing voluntary schools could not accommodate all school-age children.Footnote 20 Much of the initial impetus came from municipal boroughs (e.g., London, Birmingham) and from a 1871 survey reporting school needs in most parishes. By 1878, School Boards spanned most of England, including rural areas—90% of my sampled School Boards were in parishes with less than 5,000 inhabitants. Later, several Acts extended education, making it compulsory at ages 3-11 (1880) and free (Fee Grant Act 1891).Footnote 21 Overall, School Boards had a positive impact on schooling (Mitch 1992). Where School Board activity was effective, intergenerational mobility increased (Milner 2022). That said, School Boards did not reach everyone—by 1895, as many children attended board schools as voluntary schools run by Church of England (Sutherland 1973, p.350). In this paper, I will show that differences in land concentration resulted in an uneven expansion of schooling within England.

2.2 Great Landowners’ incentives

The historical evidence lends credence to the conceptual framework of Galor et al. (2009). Universal compulsory schooling generally met the resistance of rural, landed interests in late-19C England (Sutherland 1973, pp.115-125). Great landowners opposed local taxes by School Boards. The main reason was a lower complementarity between land and human capital; they argued that schooling did not increase the value of land. Offer (1981, p.164) summarizes this view when describing the dogma of the Conservative party, to which most landowners adheredFootnote 22:

‘Local’ or ‘beneficial’ taxation for paving the streets, laying sewers and similar expenditure was admissible; it increased the value of land and was therefore a legitimate charge on tenure. Not so the poor rates and the costs of prisons, asylums, hospitals, trunk roads, and schools.

Appendix F presents additional evidence on the lower complementarity between land and human capital than between human and physical capital based on the distribution of employment. Data from Long (2006) shows that 47.7% of those employed in agriculture in 1881 had attended school in 1851. The corresponding figure for those employed in manufacturing was 60.7%.Footnote 23 The appendix also presents evidence on the raising demand for human capital in the industrial sector after 1870. Finally, it examines urban-rural wage differentials (Clark 2005) and reviews research showing that rural migration increased rural wages and responded to changes in the industrial sector—particularly, to a higher demand for education (Williamson 1990; Boyer and Hatton 1997). Specifically, by 1881, rural migrants where positively selected in terms of education and the benefits of migrating from rural to urban areas were two times larger for those who had attended school in 1851 (Long 2005). Altogether, this suggests that the expansion of education could exacerbate the loss of rural labour force, which provided landowners with economic incentives to oppose the 1870 Education reform.

In addition, great landowners disliked School Board taxes even though the formal liability fell on the occupiers of land, i.e., the tenant farmers that rented most of their lands. The Conservative party, representing landowners’ interests, argued that such land taxes were ultimately shifted to landowners (Offer 1981, p. 163-4). Ricardian economics was used as proof. Liberals admitted that landowners were effectively liable, but argued that this burden was their hereditary obligation (ibid). These different dogmas show that, beyond taxation, the landowners’ ideology (Liberal or Conservative) shaped their view on School Boards.

After 1870, great landowners were galvanized into “a flurry of activity to ward off the dread intrusion of a School Board” (Thompson 1963, p. 208). One way in which they opposed School Board activity was by capturing them. Great landowners used their local power to secure the election of Board members pledged to their interests, who would then lower local taxes for education. Lawson and Silver (2013, p. 319) describe board elections as:

sectarian battles between Church of England and nonconformity, between candidates pledged to educational development and those pledged to save the ratepayers’ money, or between political parties ... Some of the smaller boards in rural areas were controlled by people who had opposed their creation, and were pledged to restrict their activities.

The election system facilitated the capture of School Boards by great landowners: First, because only those paying an annual rent of £10 or owning land valued at £10 could vote in Board elections. Second, because Board elections were based on cumulative voting, which favoured the election of candidates supported by great landowners (Stephens 1998). In addition, many great landowners were peers, a political elite that dominated local politics in rural areas. According to Allen (2009, p. 301), “[i]t is hard to exaggerate the extent to which [the peerage] ruled Britain through its control over ... public offices.” The large political power of great landowners likely helped them influence Board elections.

Another way in which great landowners opposed School Boards is by increasing their non-tax donations to anglican voluntary schools (Thompson 1963, p. 208). This was intended to foster voluntary schooling and, hence, reduce the need to introduce new board schools; which were not managed by religious societies and where no religious catechism was taught. This suggests that landowners were not openly hostile to schooling (Clark and Gray 2014), but preferred a voluntary-provision system with anglican religious schools.Footnote 24 A testable implication is whether the landowners’ support for voluntary schooling offset their negative effects on School Board activity. If not, this would reflect externalities and market failures similar to a private-provision system (Galor and Zeira 1993).Footnote 25

A full account of all the interest groups is beyond the scope of this paper, but I highlight three beyond great landowners. First, the Church of England was mostly aligned with great landowners’ interests, particularly in supporting voluntary schools (Stephens 1998). Second, the tenants who rented the great landowners’ lands usually complied with the latter’s political views.Footnote 26 Since they shared the burden of taxation, great landowners would likely hire tenants with similar views on key issues like School Boards and support their election to the Boards. In 1871, the Liberal party tried to break the tenant-landowner unity of action, but their policies “failed completely as political banners” (Offer 1981, p. 179). Third, yeomen, as other smaller landowners in Europe (Tollnek and Baten 2017; Baten and Hippe 2018), were supportive of schooling. Yeomen’s children, especially those with non-conformist beliefs, were more likely to attend board schools than great landowners, 95% of whom attended five Public Schools—Eton, Harrow, Rugby, and Westminster (Bateman 1883). Hence, one would expect more board schooling where yeomen owned a larger share of land.

In sum, the theoretical frameworks and historical evidence suggest a negative relation between land concentration and education provision. I empirically investigate this relation using deep-rooted historical and geographic determinants of land concentration (Sect. 5) as well as contemporaneous, 19C land concentration (Sect. 6). I then explore the mechanisms outlined here: the great landowners’ economic incentives; their political power and Conservative affiliation; their support for voluntary and opposition to board schooling; a demand channel; and the role of smaller landowners.

3 Data

3.1 Sources and main variables

State education data to study the expansion of state education, I computerize the annual reports of the Committee of Council on Education. The reports cover 1871-1899, most of the period when School Boards were active. They provide a wide range of education measures. On School Board funding, I compile the local tax rate and the total funds raised from taxation, Parliament grants, school fees, and other sources. On expenditures, I collect the money spent in board schools and aggregate investments in all schools (board and voluntary): the number of certified teachers and female class assistants and their salary expenditures. I normalize all monetary amounts by the number of children aged 5 to 10, based on the 1881 Census. On schools, I record the number of board and voluntary schools (anglican, wesleyan, non-conformist, and catholic). On human capital of children in all schools, I record the percentage passing the reading, writing, and arithmetics’ national exams. On proxies of education demand in all schools, I record the number of pupils attending, enrolled, or examining, broken down by age and by standards (see Appendix Table A4). For illustration, Appendix Figure A1 shows parts of a report.

I compile the data at two different levels: at the local and at the county level. First, I digitize the local tax rates set by all 1,387 School Boards operating in 1873–78;Footnote 27 the initial years after the 1870 reform. Second, I add the other variables for all 40 counties in England in 1871–99.Footnote 28 This is because all aggregate investments in board and voluntary schools, their numbers, and exam results are only reported at the county level. Overall, my dataset contains 23 different education measures. This allows me to evaluate many dimensions of education on which existing historical studies—restricted to literacy and enrolment rates—remain silent.

Historical land concentration I use the Domesday Book, a survey of all landholdings commissioned after the Norman conquest (1086). No survey approaching its extent was attempted until the nineteenth century. The Domesday covers most of England—except northern counties, London, and Winchester (Harvey 1971: 770). For each manor, it lists the owner and the value of the land before and after the conquest.Footnote 29 Here, I use the Domesday electronic version digitized by Palmer (2010), which provides records for 22,634 manors in 1086.

I measure historical land concentration as the percentage of land value owned by the five largest landowners in each 25-mile radius around the 1,387 School Boards for the local-level analysis (in each county for the county-level analysis).Footnote 30 To capture land inequality generated by the 190 Norman landowners that received land from William the Conqueror, I exclude Church and Crown estates from both numerator and denominator of the percentage. I measure land concentration in land values, not landholdings’ size because the Domesday only provides the former. These land values are based on taxes. To get a measure similar to concentration in landholdings’ size, I use land values based on taxes on the landholdings’ size and ignore taxes on the presence of mills, markets, or justice (Palmer 2010).Footnote 31

Contemporaneous land concentration I digitize a new dataset on 19C landownership from Bateman (1883). Bateman provides an entry for each owner of 3,000 acres or more and for 1,300 owners of 2,000 acres or more in the 1870s (henceforth, great landowners). Entries list the the great landowner’s family seat, the acres he owned in each county, and other information—see Appendix Figure A2.Footnote 32 I compile this individual-level data for all great landowners who were also in the peerage. I add geo-references for 532 seats listed in the book or in Burke (1826), and indicators for old families based on Shirley (1866).Footnote 33 Old families are those which by 1870 held land in England in unbroken male line since Henry VII’s reign (1485–1509). Finally, Bateman’s appendix reports the total arable acres owned by great landowners, squires (1,000-3,000 acres), yeomen (100-1,000), and small proprietors (1-100) in each county. I compile this data for all counties in England.

I measure land concentration at two levels: For the analysis at the local level, I use the average acres of all great landowners whose seats are located in a 25-miles radius around each School Board. I consider acres only in the county where a great landowner’s seat is located rather than his total acreage, which may include estates elsewhere in Britain or Ireland. Note that this measure only includes peer great landowners. For the analysis at the county level, I use the percentage of arable land in each county owned by all great landowners.Footnote 34

Geographic determinants of land inequality In addition to the Norman conquest, I consider another deep-rooted determinant of land inequality: geographical variation in soil texture. Specifically, sandy and chalky soils are associated with landownership concentration (Cinnirella and Hornung 2016). Since soil texture does not change over time and cannot be altered by human intervention, I use modern-day soil textures from the British Geological Survey, reported by 1x1km cells. For the local-level analysis, I use an indicator for sandy and chalky soils in the cell where each School Board is located. For the county-level analysis, I compute the percentage of sandy and chalky soils in each county.Footnote 35

Peers’ biographies I measure the political power of the 19C great landowners using their biographies in thepeerage.com (Lundy 2018), which are based on several peerage records (see Figure A3). Using regular expressions, I record appointments to Lord Lieutenant, Deputy Lieutenant, High Sheriff, Sheriff, and Member of Parliament (MP). I record the political affiliation of great landowners, and whether they gained or lost a seat in Parliament in the 1874 general election.

Other I collect geographic and climate covariates at a highly disaggregated level: terrain ruggedness (Nunn and Puga 2012), suitability for cereal, pasture, and tubers (FAO 2007), 19C temperatures (mean and standard deviation; Luterbacher et al. 2006), precipitation (ESRI), and distance from School Boards to the sea and rivers (Ordnance Survey 2018).Footnote 36 I compute the distance to industrial centres and cathedrals. I collect the population of the district served by each School Board from the Reports of the Committee of Council on Education, and the county-level population density (children under 5 per sq. km) from the 1881 Census. I also use county-level employment in manufacturing, income p.c., religiosity, and the share of non-conformists from the 1871, 1881, and 1891 Census (Hechter 1976). Finally, I use Roman roads (McCormick et al. 2013) to construct proxies for pre-1066 economic development. All variables are described in detail in Appendix B.

3.2 Data descriptives

Here I discuss descriptive statistics for my main variables (see Appendix Table A1 for complete descriptives). Most of the funds raised by School Boards came from taxation. In 1873–78, the average tax rate was 2.5 percent. This amounted to 80 pence per child in the average county. Other sources of School Board funding, e.g., Parliament grants and fees, have a lower mean and standard deviation, suggesting that local differences were mostly associated with differences in taxation.

School Boards in the average county spent 150 pence per child in board schools. As explained above, board schools coexisted with voluntary schools, funded through non-tax donations and Parliament Grants. Specifically, the average county had 103 board vs. 353 voluntary schools per square kilometre.

The percentage of children passing the national exams in both board and voluntary schools was high. Rather than educational progress, this reflects the fact that Parliament grants were partly based on children’s grades (Green 1990, p. 7). That said, there is meaningful variation across counties, especially in arithmetics. Hence, I can assess whether underinvestment in schooling affected human capital accumulation in this dimension.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that education provision is negatively associated to landownership concentration. Figure 1 shows the case of Macclesfield and Cottenham. The lands around these two School Boards were distributed differently. This can be traced back to the land redistribution that followed the Norman conquest. In 1086, around Macclesfield, 40% of the land was given to five landowners. Around Cottenham, the corresponding figure was ‘only’ 25%. These differences persisted over centuries. By 1870, Macclesfield was surrounded by seats of great landowners (blue circles). Larger landholdings (larger circles) emerged where the Normans redistributed land more unequally (darker cells). On average, great landowners near Macclesfield owned 11,700 acres in the county. Differently, Cottenham was surrounded by fewer 19C great landowners who, on average, owned ‘only’ 5,000 acres in the county. These persistent differences in landownership are associated with different levels of education provision. Macclesfield set taxes at only 0.96% between 1873 and 1878. Instead, the lower land concentration around Cottenham seemingly facilitated the expansion of education. Cottenham set taxes at 3.3%—more than three times larger than that in Macclesfield.

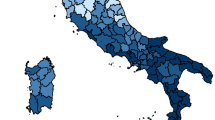

These examples are not exceptional. Figure 2 shows the geographical distribution of land concentration in 1086 (panel a), land concentration in 1870 (panel b), and School Board taxes and the funds raised from taxation (panel c). The top panels use local-level data from 1,387 School Boards and 532 great landowners’ seats, the bottom panels use county-level data. Although there is variation across and within areas, three general patterns emerge:

First, it is hard to exaggerate the extent to which land was concentrated in 19C England: The average great landowner owned an estate of 8,000 acres in the county where his seat was located. Overall, 40% of all the lands belonged to them.

Spatial distribution of local taxes for education and land concentration. Notes: Top for local-level data: (a) av. tax rate in 1873-78 by 1,387 School Boards; (b) land concentration in 1086; (c) acres in county by 532 seats. Bottom for county-level data: (a) av. funds from taxes in 1871-94; (b) land concentration in 1086; (c) land concentration in 1870

Second, land concentration in 1870 is remarkably similar to that in 1086. The largest 19C estates (dark blue dots) emerged in areas where large Norman landowners received a higher percentage of land (dark purple dots). The persistence of land inequality is also evident at the county level. For example, in Cheshire, 68% of the land was owned by the five largest Norman landowners. Eight centuries later, 52% of the land was owned by great landowners. In contrast, in counties between the Walsh and the Severn estuaries, the Norman land grab was smaller and so was landownership concentration in 1870.

Third, the spatial distribution of education funds and land concentration are opposite. At the local level, landownership was more concentrated in 1086 and in 1870 mostly in the north. In contrast, School Boards imposing the largest tax rates (dark brown dots) were mostly in the south-east, where the land distribution was historically relatively more equal. This is also visible at the county level. For example, counties in the West Midlands only raised 7-21 pence per child and land there was heavily concentrated: 30-80% of the land belonged to the five largest Norman landowners and 40-70% to 19C great landowners.

To visualize these two patterns, Figure 3 presents binned scatter plots.Footnote 37 Panel (a) uses local data to show that areas where land was more concentrated in 1086 are also the areas where great landowners own the largest estates in 1870. In turn, where land was more concentrated in 1086, we observe lower tax rates for education. Panel (b) reproduces these two patterns at the county level.

Taken together, these descriptives suggest that the Norman conquest laid the groundwork for inequality in England. This land inequality persisted until the 19C, when it distorted education provision by local School Boards.

4 Persistence of land inequality

My first goal is to investigate the deep roots of the relationship between inequality and education provision. Here I examine Engerman and Sokoloff (2000)’s prediction that land inequality can persist over centuries and is deep-rooted in historical and geographic factors (Sect. 5 examines the reduced-form effect of these deep-rooted factors on 19C education provision). Specifically, I discuss how the Normans redistributed landownership in 1066 and how much this reshaped land inequality. I then examine empirically the persistence of historical land inequality from 1066 to the reign of Henry VII (1485–1509) and to the 19C. I contrast these estimates with the contribution of geographical factors to land inequality. Finally, I test alternative channels of persistence that, potentially, could confound the reduced-form effect of historical land inequality on 19C education provision.

4.1 The Norman land redistribution

In 1066, William the Conqueror crossed the Channel from Normandy, defeated the Anglo-Saxons in Hastings, and became King of England. One of his first acts was to redistribute landownership: He took one fifth of the land for himself, gave a quarter to the Church, and divided the remaining 55% among 190 Norman nobles. How were these lands assigned? Brooke (1961) suggests that William gave land in a more concentrated manner in areas with threats specific to the eleventh century. The receivers of land had to provide the King with a number of knights proportional to the size of their landholdings.Footnote 38 Hence, larger landholdings were given in conflict-prone areas—e.g., where Anglo-Saxons threatened with rebellion.

William’s land redistribution laid the groundwork for inequality. Before the conquest, England was a mosaic of landowners (Cahill 2001). To illustrate this, I identify the 4,690 farms given to 29 Norman nobles who fought in the Battle of Hastings and/or appear in the Bayeux Tapestry—a Norman embroidery depicting the conquest. Table 1 lists the number of owners in these farms before and after the conquest. For example, in Buckinghamshire, 285 farms that used to have 181 different owners were given to 10 Norman nobles. Overall, the surveyed farms saw a 93% reduction in the number of landowners. In other words, the conquest resulted in a massive increase in landownership concentration.

4.2 Land persistence estimates

Here I examine empirically the persistence of land inequality from the Norman conquest to the 19C. I also discuss the evolution of the land market and the legal mechanisms that enforced the persistence of the great estates.

Formally, I examine the persistence of land inequality by estimating:

where i indicates a 25-miles area around each of the 1,387 School Boards under analysis. Land concentration in 1870, \(L^{1870}\), is the average acres of all 19C great landowners whose seats are located in i. I consider acres only in the county where a landowner’s seat is located rather than his total acreage, which may include estates elsewhere in Britain or Ireland. The variables \(L^{1086}_{i}\) and \(G_{i}\) capture two deep-rooted determinants of land inequality: one historical, another geographical. The historical determinant of land inequality, \(L^{1086}_i\), is the percentage of land value that in 1086 was given to the largest five landowners in i. The main geographical determinant of land inequality, \(G_i\), captures variation in soil texture, a factor that Clark and Gray (2014) deem important for land concentration in England. Specifically, \(G_i\) is an indicator for the presence of sandy and chalky soils over 1x1 km cells. Sandy and chalky soils are typically associated with land concentration because these soils do not retain water well, are drought-prone, and, hence, worse for agriculture (Leeper and Uren 1993). In turn, areas with less productive agriculture are subject to lower population pressure and a weaker land demand. As a result, landownership tends to be concentrated in the long run. In extended specifications, \({{\textbf {X}}}_i\) includes a broad set of geographic and climate covariates which, under Engerman and Sokoloff (2000)’s framework, may also be important determinants of land inequality and of later education provision.

I also examine the persistence of land inequality at the county level:

where \(L^{1870}_{c}\) and \(L^{1086}_{c}\) are the percentage of land in county c owned, respectively, by great landowners in 1870 and by the county’s largest five landowners in 1086. The variable \(G_{c}\) is the percentage of sandy and chalky soils in county c and \({{\textbf {X}}}_c\) includes geographic and climate covariates at the county level.

Table 2 documents a strong persistence in land inequality from the Norman conquest to the 19C. Panel A reports standardized beta coefficients from estimating Eq. (1). The largest estates in 1870 arose in areas where land was more concentrated in 1086. A percentage point increase in historical land inequality is associated with an increase of 70 acres in the size of the landholdings of an average 19C great landowner around a School Board (column [1]).

Geographic characteristics are also important long-run determinants of land inequality. Larger estates emerged in areas with sandy and chalky soils. This relation between soil texture and land inequality is consistent with previous findings for England but also for Prussia and India.Footnote 39 Importantly, the coefficient on soil texture remains significantly different from zero conditional on land concentration in 1086. In other words, soil texture seems to have a compound effect over time, increasing 19C land concentration over and above the level of land concentration already present in 1086. In contrast, in Engerman and Sokoloff (2000)’s framework geography determines the level of land concentration around critical junctures rather than as part of a process of continuing concentration.

Beyond soil texture, I consider a broad set of geographic and climate covariates which can also be considered long-run determinants of land inequality. In column [2], I add terrain ruggedness and the geographic suitability for cereal, pasture, and tuber production—the main crops grown in England. Rugged terrains were dominated by small family farms in England (Clark and Gray 2014). Cereals dominate in the midlands and in the south east. The south west was predominantly pastoral and tubers were grown in the north east. These different crops are associated with different economies of scale, and hence, with different landownership structures. Consistent with Clark and Gray (2014)’s predictions, I find that terrain ruggedness is negatively associated with large estates and that the suitability for different crops predicts regional differences in land concentration in 1870. In column [3], I add climatic covariates: precipitation and the mean and standard deviation of temperature. Precipitation is an important pre-condition for large-scale agriculture (Baten and Hippe 2018, p. 15). Together with temperature, it affects the length of the growing season, which Clark and Gray (2014) identify as an important determinant of land concentration in England. I find that precipitation is positively associated with land concentration, reflecting the fact that it is a pre-condition for large-scale agriculture. That said, the F-statistic of the joint test of all these geographic and climate covariates is around 20, half of that corresponding to land concentration in 1086. Similarly, the estimated effect for soil texture is smaller than that of land concentration in 1086 across specifications. This suggests that historical determinants of land inequality top geographic determinants in this setting.

In columns [4] and [5], I add the distance to the coast, rivers, 19C industrial centres, and cathedrals as well as population served by each School Board in the 19C. These covariates have little impact on the main coefficients of interest. Yet, some of the estimates are interesting in its own right: Land inequality is larger in areas further from industrial centres, rivers, and the coast. Overall, the Conley (1999) and robust standard errors are similar, suggesting that my estimates are not driven by spatial correlation. In addition, results are robust to calculating land concentration using a 10-, 15-, and 20-miles’ cut-off around School Boards.

Panel B reports standardized beta coefficients from Eq. (2). The persistence of land inequality is also visible at the county level. Counties where land was more concentrated in 1086 also had a more concentrated landownership in the 19C. A one ppt increase in the land owned by the five largest landowners in 1086 is associated with an increase of 0.26-0.35 ppts in the land owned by great landowners in 1870. The magnitude of the persistence is large: increasing land inequality in 1086 by one standard deviation would increase land inequality in 1870 by more than half a standard deviation. As before, this effect is larger than that of soil texture and geographic and climate factors (cols. [2]-[3]). The combined F-statistic is 3.8 for the latter vs. 10.6 for land concentration in 1086. Including the full set of controls does not alter the persistence in land inequality (cols. [4]-[5]).

Admittedly, land was not transferred directly from the 1066 Norman lords to the nineteenth-century great landowners. Some Norman families died out and their lands were acquired by other landowners. This gave rise to new landowning classes, like the yeomen (Mokyr 1993), in the late-middle ages. In the early-modern period, the gentry benefited from the dissolution of the monasteries (Heldring et al. 2021), but the aristocracy’s share of land in England remained virtually unchanged from 1436 to 1688 (Overton 1996, Table 4.8). In contrast, in the 18C, there was “a drift in property ... in favor of the great lord" (Habakkuk 1940, p. 2,4). From 1750, the great estates were stable (Beckett 1977, p. 567). Despite these episodes, the strong spatial correlation between the land inequality in 1086 and in 1870 suggests that the large Norman estates consolidated and, to some extent, survived over eight centuries—even if the families owning them changed or, in some periods, sold parts of their lands.

To evaluate this hypothesis quantitatively, I examine the persistence of land inequality from 1086 to the 1500s. This midpoint absorbs the early processes discussed above, e.g., the rise of yeomen, but stands before Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries and the 18C property drift towards great lords. Unfortunately, no land survey approaching the extent of the Domesday is available for this time. Instead, I proxy for land inequality in the 1500s using Shirley (1866). This genealogy identifies the families who held land in England from Henry VII’s reign (1485–1509) to the 19C in unbroken male line.Footnote 40 I combine this information with the landholdings in Bateman (1883) and evaluate the size (in 1870) of the estates owned by old families who held land from the 1500s to 1870.

Panel C reports standardized beta coefficients from Eq. (1) using the measure defined above as dependent variable. I find a strong persistence from 1086 to the 1500s. The estates of old families who held land from the 1500s to 1870 arose where land was more unequally redistributed in 1086. Specifically, one ppt increase in land concentration in 1086 is associated with an increase by 110-120 acres in the estates of these old families. As expected, this estimate is larger than that capturing persistence from 1086 to 1870. As before, this relationship is robust to controlling for the full set of geographic, climate, and population controls.

In addition, Appendix Table A12 shows that the land redistribution in 1086 is associated with the share of land in a county owned by great landowners, but not to the corresponding share by squires, yeomen, and small proprietors.Footnote 41 Hence, although some of the lands redistributed in 1086 were later acquired by smaller landowning classes, this did not happen systematically where land inequality was higher. In other words, it did not break the large concentration of landownership in some areas of England. I discuss small landowners in more detail in Sect. 6.1, where I evaluate their role for education provision.

Altogether, the evidence suggests that land inequality, particularly at the top of the distribution, survived over eight centuries—despite the extinction of some Norman families and the emergence of other landowning classes. Engerman and Sokoloff (2000) suggest several institutional mechanisms through which inequality can persist over such long periods. One such mechanism is norms and legal instruments that consolidate large estates and restrict land access. In my setting, social norms partly enforced the persistence of great estates. Selling land was stigmatized among the landed elite (e.g., Stone and Stone 1984, p. 78). In addition, most estates remained unbroken from 1650 thanks to the strict settlement. With this contract, aristocrats forced their heirs to pass down the family estate intact to the next generation—estates could not be partitioned, sold, or mortgaged (Habakkuk 1994). According to Habakkuk (1950, p. 18), “about one-half of the land of England was held under strict settlement in the mid-eighteenth century.” This legal instrument likely contributed to the persistence in land inequality documented here.

4.3 Other channels of persistence

So far, I argued that land inequality in England was deep-rooted in the Norman land redistribution. Before examining its reduced-form effect on 19C education provision, I test alternative channels of persistence which, potentially, could directly affect education provision without resort to the persistence of land inequality.

Pre-conquest economic development The land distribution after the Norman conquest may have reflected local differences in pre-conquest economic development. If these differences persisted up to the 19C, they could directly affect state education provision. That said, Darby et al. (1979) show that the regional distribution of income changed substantially after the Norman conquest. In addition, Brooke (1961) suggests that land was not given in a more concentrated manner in richer areas but in areas with military threats specific to post-conquest England that were eventually controlled.

To substantiate this, I show empirically that land concentration in 1086 is orthogonal to local pre-conquest economic development. To proxy for the latter, I use the density of Roman roads—which promoted development through trade and city growth. Importantly, even though Roman Britain collapsed long before the Norman conquest, elsewhere it has been shown that the density of Roman roads reflects economic conditions centuries later (Wahl 2017; Dalgaard et al. 2022).

Table 3 shows regressions of the density of Roman roads in 410 on land concentration in 1086 and the full set of geography and climate controls. The unit of observation is a 10x10 mile cell (see Appendix Figure A5). Associations are close to and not significantly different from zero: a one standard deviation increase in land concentration in 1086 is associated with a 0.06-0.08 standard deviation reduction in Roman road density (cols. [1]-[2]). The magnitude is substantially lower than the persistence of land inequality (Table 2).

Post-1066 institutions, religion, and local development Norman reforms—other than redistributing land—could have triggered local differences in institutions, religion, or development within England which persisted until the 19C. This is unlikely. According to Angelucci, Meraglia, and Voigtländer (2017, p.1), the conquest “resulted in largely homogenous formal institutions across England.” The Normans introduced institutional and religion reforms (e.g., feudalism, church reform), but they did so nationwide. The authors show that local differences in institutions emerged when some boroughs were granted a Charter of Liberties (before 1348). These boroughs were typically close to Roman roads (ibid, p. 3)—which, as shown before, is orthogonal to the land concentration in 1086.

I confirm this hypothesis empirically by showing that land concentration in 1086 is not associated with a range of regional economic and religious characteristics from the 1871 Census. Table 3 presents regression results with my full set of controls. All variables are at the county level and are standardized to facilitate the interpretation of the magnitudes. Columns [3] and [4] show that a one standard deviation increase in land concentration in 1086 is associated with a 0.04 standard deviation increase in income per capita and with a 0.03 standard deviation reduction in the share manufacturing workers in the late 19C. These two estimates are 15-20 times smaller in magnitude than the persistence of land inequality and are not significantly different from zero. This suggests that the Norman land redistribution neither triggered differences in local development nor significantly affected the pace of industrialization. In columns [5] and [6], I look at the share of non-conformists and religiosity. As explained in Sect. 2, non-conformists played an active role in the expansion of state education in 1870. That said, land concentration in 1086 is not significantly associated with these variables: estimates are three times smaller than those for the persistence of land inequality.Footnote 42 Finally, column [7] shows that soil texture is also balanced across counties with different levels of land concentration in 1086.

Capital destruction in 1066 If the capital destruction brought by the Norman conquest triggered long-run local differences in economic development, outcomes such as education provision may be affected. This caveat is important: my measure of historical land inequality is based on land values in 1086, which might reflect capital destruction or casualties related to the conquest. To address this, Appendix D defines historical land inequality using the pre-conquest values reported by the Domesday for a sub-sample of manors. Although the number of observations is reduced, my main conclusions are robust.

Church and Crown estates A reduced-form effect of historical land inequality on later outcomes may be driven by the lands that William took for himself or gave to the Church instead of those given to Norman nobles. Some Crown estates were sold to the gentry in 1436–1688 and monasteries were dissolved in 1535 (Overton 1996: Table 4.8). These events triggered local differences in development (Heldring et al. 2021) which, in turn, may have affected 19C education provision. My results are not confounded by these effects because I measure historical land inequality excluding Church and Crown estates from both numerator and denominator of the land concentration percentage.

Altogether, these results suggests that, while the Norman land redistribution was not random, it neither reflected underlying economic factors nor triggered persistent local differences in income per capita, industrialization, or religious composition. Only land inequality seems to have deep roots in the Norman conquest. This evidence suggests that the relation between historical land concentration and later education provision is plausibly not driven by omitted factors.

5 Reduced-form effects

This section examines Engerman and Sokoloff (2000)’s prediction of a negative reduced-form relation between historical and geographical deep-rooted determinants of land inequality and later education provision. To do so, I estimate:

where \(y_{i}\) is the average education tax rate set by School Board i in 1873–78. The historical determinant of land inequality, \(L^{1086}_i\), is the land concentration after the Norman conquest. The main geographical determinant of land inequality, \(G_i\), captures variation in soil texture. Both variables are defined as in Sect. 4. In extended specifications, \({{\textbf {X}}}_i\) includes the same geographic and climatic determinants of land inequality as before. The full specification includes the distance to cathedrals and industrial centres and the population served by each School Board.

I also examine the relation between land inequality and other sources of School Board funding, and aggregate expenditures and human capital accumulation in both board and voluntary schools. Unlike the education tax rates set by School Boards, this data is on the county level. I use a panel of 32 counties to estimate:

where \(y_{c, t}\) is an education measure, e.g., teachers’ salaries, in county c at year t. The remaining variables are analogous to those defined above but calculated at the county level. To account for the panel structure, I include year fixed effects, \(\mu _t\). Hence, the \(\beta\)-estimate is obtained by pooled cross-section OLS.

Table 4 presents estimates of Eq. (3) for 1,387 School Boards.Footnote 43 In column [1], I show a strong negative association between historical land concentration and local education provision: School Boards set lower education taxes in 1873-78 where land was more unequally distributed by the Normans. Specifically, increasing historical land concentration by one standard deviation is associated with a reduction in tax rates of 0.2-0.25 percentage points (ppts). Given that the average tax rate was only 2.5, the estimated effects amount to a decrease of 8-10%.

Education taxation is more strongly associated with historical than with geographic determinants of land inequality. My estimates suggest that the presence of sandy and chalky soils is associated to a 0.1 ppts reduction in tax rates for education. The estimated coefficient is marginally significant and smaller in magnitude than that of land concentration in 1086. Note that this smaller magnitude does not imply that soil texture was unimportant for education provision, but that it did not have a large direct effect conditional on land concentration in 1086. Appendix Table A6 shows the unconditional effect of soil texture on education provision. That is, it shows separate regressions using soil texture or historical land concentration as the main explanatory variable. The unconditional estimates for soil texture (i.e., excluding the historical land concentration variable) are 40% larger in magnitude than those in Table 4. Specifically, the presence of sandy and chalky soils is associated to a 0.15 ppts reduction in tax rates for education, an effect that is significantly different from zero. That said, this unconditional effect is smaller in magnitude than the unconditional effect of historical land inequality. This suggests that soil texture, a geographical determinant of land inequality, was important for later education provision, but that most of its effect acted through land inequality in 1086. In other words, soil texture may have affected land inequality after 1086, but this did not have a large direct effect on education provision over and above the degree of land concentration in 1086.

In columns [2] and [3] of Table 4, I consider a broad set of geographic and climate covariates: terrain ruggedness, suitability for cereal, pasture, and tuber production, precipitation, and the mean and standard deviation of late-19C temperatures. As shown before, these factors are associated with land inequality. Hence, under the Engerman and Sokoloff (2000) framework, we would expect them to have a reduced-form effect on education provision. Consistent with Clark and Gray (2014), however, I find that the geographic and climate factors above are poor predictors of 19C education provision in England. A joint hypothesis test for these covariates suggests they are marginally significant predictors. Specifically, the F-statistic of the joint test is 1.81, with an associated p-value of 0.08.Footnote 44

Importantly, geographic and climate covariates are also potentially correlated with agricultural productivity and local incomes, and hence, may have determined the wealth available for taxation in rural areas. That said, the estimates on land concentration in 1086 are similar in magnitude in columns [1] to [3]. This suggests that the relationship between historical land concentration and later education provision is not driven by systematic geographic and climatic differences between areas where the Normans redistributed land more unequally.

In column [4], I add location covariates: the distance from each School Board to the closest river, coast, industrial centre, and cathedral. Proximity to the water bodies may have been important for local development in the long run by fostering trade, the use of steam power, or early industrialization. Proximity to an industrial centre may have provided families with incentives to acquire schooling because migrating to an industrial centre was easier. Proximity to a cathedral proxies for cultural and religious factors. The estimate for land inequality is robust.

In column [5], I add the population in the parish, borough, or district served by each School Board. School Boards often issued by-laws exempting children living far from a school from attending. This illustrates a provision problem in scarcely populated areas (Boucekkine et al. 2007). If the areas where land was historically more concentrated were also scarcely populated, the strong association in column [1] may be spurious. Column [5] shows that this is not the case. If anything, the estimate for land inequality increases in magnitude, suggesting that areas where land was historically more concentrated where not systematically less populated. In addition, Appendix Table A8 shows that the results are robust to excluding School Boards in urban areas.

Altogether, the estimates are very consistent across specifications. This suggests that the historical land concentration resulting from the Norman conquest was an important determinant of education taxation in the 19C—over and above a broad set of geographic, climatic, and population characteristics.

Note that Table 4 reports results from spatial regressions. Hence, we may be concerned that the relation between historical land inequality and education taxation 800 years later reflects spatial autocorrelation. To address this, I follow two strategies: First, I calculate standard errors using the Conley (1999) approach, allowing for spatial dependence within 50 miles. The Conley standard errors are not significantly larger than before. Second, I follow Kelly (2019) and conduct a Moran test of spatial autocorrelation in regression residuals.Footnote 45 The p-values for the Moran test range between 0.66 and 0.7, strongly suggesting that residuals are not spatially autocorrelated. Finally, results are robust to calculating land concentration around each School Board using different cutoffs. Appendix C shows that results are similar using a 10, 15, and 20 miles’ cut-off.

Next, I examine a range of education measures beyond education taxes. In Sect. 6, I use these measures to disentangle different mechanisms through which contemporaneous landowners affected schooling. Here I briefly discuss their reduced-form relationship with historical and geographical determinants of land inequality.

Table 5 presents estimates of Eq. (4) at the county level. Panel A shows a negative reduced-form relationship for all the sources of School Board funding: Increasing land concentration in 1086 by 10 ppt is associated to a reduction in funds from taxes, Parliament grants, fees, and other sources by 15, 9, 3, and 0.5 pence per child (cols. [1]-[4]). As expected, the magnitude is larger for taxes, the main funding source. Importantly, these results show that other funding sources did not compensate for the low taxes where land was historically concentrated. Panel A also shows that fewer School Boards were established and expenditure in board schools was lower where land was historically concentrated (cols. [6]-[7]).

Panel B shows that education under-spending in board schools was not compensated by voluntary schools. The number of teachers and their salaries in all schools were lower in counties where land was historically concentrated (cols. [1]–[3]). In those counties children attending all schools were less likely to pass the national exams (cols. [4]–[7]), especially in arithmetics—a skill in demand at the time (Mitch 1993). In detail, a 10-ppts increase in historical land concentration is associated with a 7-ppts reduction of the percentage passing arithmetics.Footnote 46 This suggests that historical inequality is negatively associated with 19C human capital accumulation.

As at the local level, education provision at the county level is influenced more strongly by historical than by geographic determinants of land inequality: The percentage of sandy and chalky soil is negatively associated with all education variables, but the estimates are smaller than those of historical land inequality.Footnote 47 The F-statistic is 3.5 for the relation between tax funds and the geographic and climate covariates listed above, plus the density of rivers and coastline length. The statistic is higher than before but still lower than that of historical land inequality (12). All specifications in Table 5 include a population density control: the number of children below 5 per square kilometre. Appendix Table A11 considers an extended set of county controls.Footnote 48 Finally, note that I report pooled-OLS estimates where education variables vary over time but landownership does not. Hence, I cluster standard errors by county (in parenthesis). In addition, Appendix Figure A4 presents estimates of Eq. (4) for each year separately. My main conclusions are robust in this cross-sectional specification.

6 Contemporaneous effects and mechanisms

So far, I documented a strong persistence of land inequality from 1086 to 1870 and a negative reduced-form effect of historical land inequality on education provision. My second goal is to examine the contemporaneous relationship between 19C land inequality and education provision. Here I investigate Galor et al. (2009)’s prediction of a negative relationship. Next, I examine the potential mechanisms behind it highlighted in Sect. 2.

To examine the contemporaneous relationship, I estimate Eqs. (3) and (4) but instead of considering two deep-rooted determinants of land inequality (land concentration in 1086 and soil texture) I use the contemporaneous land concentration in 1870 (\(L^{1870}\)).Footnote 49 As before, \(L^{1870}\) is the average acres of all great landowners whose seats are within 25 miles of each School Board in the local-level analysis and the percentage of land by great landowners in the county-level analysis.

Table 6, Panel A presents the results at the local level.Footnote 50 Land concentration in 1870 is strongly negatively associated with contemporaneous education provision. In areas where land concentration was one standard deviation larger (i.e., where the average great landowner owned 4,200 more acres) School Boards set lower tax rates by 0.2 ppts. Given that the average tax rate in 1873–78 was 2.5, this amounts to an 8% decrease. This magnitude is very similar to that estimated for historical land concentration, suggesting that the persistence of land inequality is the main driver of Sect. 5’s reduced-form estimates (Table 4).

Results are robust to including the same set of geographic, climate, and population controls as before. Estimates are very consistent across specifications. Hence, it is unlikely that results are driven by large estates emerging where education provision was unattractive for other reasons—e.g., low agricultural productivity and low local incomes associated to geography and climate; or provision problems associated with low population density. In addition, Appendix Table A8 shows that results are robust to excluding School Boards in urban areas, which concentrated much of the initial impetus in the expansion of state education. Finally, results are also not driven by spatial correlation: the Conley (1999) and robust standard errors are similar and the p-values for the Moran test are around 0.7.

Although these estimates are based on well-founded theoretical predictions, so far I have avoided causal language. I gain insights into identification from an IV estimation using the Norman land redistribution as an instrument for late-19C land concentration. The evidence in Sect. 4.3 suggests that this instrument is relevant (see Tables 1 and 2) and satisfies the exclusion restriction (see Table 3), in the sense that the Norman land redistribution did not trigger long-run local differences in development or institutions other than by affecting the land distribution. In other words, the Norman land redistribution provides variation in landownership that is plausibly unrelated to other factors making 19C education attractive. Table 6, Panel B presents second-stage estimates for the relation between education provision and land concentration in 1870 (\(L_i^{1870}\)), where the latter is instrumented with land concentration in 1086 (\(L_i^{1086}\)). The second-stage estimates show that land concentration had a strong, negative effect on local education provision. Increasing land concentration in 1870 by one standard deviation decreases the tax rates for education set by local School Boards by 0.3 standard deviations (column [1]).Footnote 51 The magnitude is similar to the reduced-form estimates in Table 4 and larger than the OLS estimates in Panel A.Footnote 52 As before, IV-estimates are robust to including the full set of geographic, climate, and population controls (columns [2]-[5]). The F-statistic in the first stage is large across all specifications, confirming that the instrument is not weak. Altogether, these results suggest that the relation between land concentration and School Board taxes is plausibly causal.Footnote 53

Next, I examine the contemporaneous relation of land concentration and various education variables at the county level. As in Table 5, I present pooled-OLS estimates where only education varies over time. This is because Bateman (1883) does not record time variation in land concentration, which was stable in the studied period (Beckett 1977, p. 567). To account for the structure of the data, all specifications include year fixed effects and cluster standard errors by county.

Table 7, Panel A looks at School Board funding. Consistent with the results at the local level, I find that counties where land was more concentrated in 1870 raised fewer funds from taxes (col. [1]). As expected, the magnitude of the estimates is slightly larger than that for historical land inequality: increasing land concentration in 1870 by 10 ppt (i.e, by one standard deviation) is associated to a reduction in these funds by 19 pence per child. School Boards also received funds from Parliament grants and fees. One possibility is that, where land was more concentrated, these other funds substituted funds from taxes on land. This was not the case: Parliament grants, fees, and other funds are also negatively associated with contemporaneous land inequality (cols. [2] to [4]). Since local taxes were the main source of School Board funding, the magnitudes in columns [2] to [4] are lower than in [1]. Overall, the total funds of School Boards were lower by 35 pence per child where land was more concentrated by one standard deviation (col. [5]).

Counties raising less funds consequently underspent on board schools. Increasing land concentration in 1870 by one standard deviation is associated with 35 pence per child fewer expenditures in board schools (col. [7]). As expected, the magnitude is similar to that of the total funds raised by School Boards.