Abstract

The effect of temperature on insect-plant interactions in the face of changing climate is complex as the plant, its herbivores and their interactions are usually affected differentially leading to an asymmetry in response. Using experimental warming and a combination of biochemical and herbivory bioassays, the effects of elevated temperatures and herbivore damage (Helicoverpa zea) on resistance and tolerance traits of Solanum lycopersicum var. Better boy (tomato), as well as herbivory performance and salivary defense elicitors were examined. Insects and plants were differentially sensitive towards warming within the experimental temperature range. Herbivore growth rate increased with temperature, whereas plants growth as well as the ability to tolerate stress measured by photosynthesis recovery and regrowth ability were compromised at the highest temperature regime. In particular, temperature influenced the caterpillars’ capacity to induce plant defenses due to changes in the amount of a salivary defense elicitor, glucose oxidase (GOX). This was further complexed by the temperature effects on plant inducibility, which was significantly enhanced at an above-optimum temperature; this paralleled with an increased plants resistance to herbivory but significantly varied between previously damaged and undamaged leaves. Elevated temperatures produced asymmetry in species’ responses and changes in the relationship among species, indicating a more complicated response under a climate change scenario.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Consideration of asymmetry in plant-herbivore responses to climate warming is crucial to predicting how these systems will change over time. The global average temperature is predicted to rise by at least 4.0 °C by the end of the twenty-first century, resulting in increased frequency and intensity of drought and heat waves (Field 2014; Brown and Caldeira 2017). Rising temperatures can directly affect plant-herbivore relationships as the rates of insect metabolism and consumption are temperature-dependent. Plants also face challenges when exposed to multiple stresses (biotic and abiotic), and the plant’s response to mitigate one stressor may exacerbate another (Atkinson and Urwin 2012; Suzuki et al. 2014; Waterman et al. 2019). Previous predictions of insect pest populations and crop losses postulate an increase in both with elevated temperatures (Deutsch et al. 2018). However, the effects of climate change on plant-herbivore interactions may be asymmetric, with the plant, its herbivores and their interaction affected differentially. Additionally, the changes in one member in a plant-herbivore system can affect the response of the other leading to ecological impacts that are difficult to predict.

Insect-plant interactions in a warming climate will depend upon a range of independent and interactive factors such as sensitivity of insect and host plant, changes in host plant quality (chemistry, morphology and defense responses), and herbivore feeding behavior (compensatory or antagonistic). Being ectothermic, insect herbivores are directly influenced by temperature changes. Temperature increase within a range of critical thermal minimum (CTmin) and maximum (CTmax) accelerates insect metabolism leading to higher consumption and growth (Bale et al. 2002; Berggren et al. 2009). This changes the nutritional demands of insect herbivores (Lee et al. 2015). For example, protein denaturation increases at higher temperatures, which requires herbivores to consume protein-rich plants (Angilletta and Angilletta 2009). Similarly, efficiency of N digestion are also reduced in insect herbivores (e.g Spodoptera exigua) at elevated temperatures altering metabolic demands (Lemoine and Shantz 2016).

The changes in dietary requirements of insect affect the amount of caterpillar salivary elicitors (e.g Glucose Oxidase, GOX) (Peiffer and Felton 2005; Hu et al. 2008). Therefore, increasing temperatures alter herbivory (elicitor) derived plant defense responses (Rivera-Vega et al. 2017). Glucose oxidase (GOX), the most abundant salivary protein in Helicoverpa zea and commonly found in many lepidopteran larva, is secreted by the labial salivary glands during feeding and acts as an elicitor or suppressor of plant defenses, depending upon the host plant (Musser et al. 2002, 2005). Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is one of the enzymatic byproducts of GOX activity and acts as a secondary messenger that induces plant defenses in tomato (Orozco-Cárdenas et al. 2001; Tian et al. 2012).

Plant vegetative growth and reproductive success are strongly dependent on temperature. Each species in a particular environment has a specific or optimum temperature range for maximum productivity (Hatfield and Prueger 2015). For example, heat stress in most tomato varieties occurs at a mean temperature of 28–29 °C, a few degrees above the optimum range of 21–24 °C (reviewed by Hazra et al. 2007). Plant’s growth and reproductive success are compromised at above-optimum temperatures as photosynthetic ability is affected, resulting in limited energy reserves (Berggren et al. 2009; Sharkey and Zhang 2010; Sumesh et al. 2008; Todorov et al. 2003).

Temperature change induces phytochemical and morphological changes in host plants. In tomato (S. lycopersicum var. Heinz), the concentration of catecholic phenolics (chlorogenic acid and rutin) were significantly higher at a nighttime temperature of 17 °C than at other temperatures (Bradfield and Stamp 2004). Similarly, Rivero et al. (2003) reported a low level of polyphenol oxidase(PPO), peroxidase (POX) activity at 35 °C in tomato (S. lycopersicum cv Tmknvf2); Green and Ryan (1973) reported a significant reduction in the activity of protease inhibitors in tomato (S. lycopersicum var. Bonnie Best) at temperatures below 22 °C. Peroxidase activity in St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum cv. Topas) was, in contrast, increased at elevated temperatures (Zobayed et al. 2005). The density of leaf trichomes typically increases at elevated temperatures (Ehleringer and Mooney 1978; Pérez-Estrada et al. 2000; Bickford 2016). Limited information, however, exists on the combined effect of elevated temperature and insect herbivores on induction of plant defenses (Bidart-Bouzat and Imeh-Nathaniel 2008).

Studies on warming-induced changes in host plant quality and subsequent effects on herbivore performance have produced mixed results (Jamieson et al. 2017; Zavala et al. 2008; Zvereva and Kozlov 2006). In alfalfa (Medicago sativa), concentrations of plant secondary metabolites (sapogenins and saponins) were increased at higher temperatures, depressing caterpillar growth (Spodoptera exigua). In contrast, the Green-veined butterfly (Pieris napi) responded to warming-mediated poor-quality foliage in Brassicaceae by consuming a significantly higher amount of plant tissue (Bauerfeind and Fischer 2013). The performance of aphids (Myzus persicae and Brevicoryne brassicae), however, was not affected when fed on oilseed rape plants with differences in nutritional quality exposed to different temperatures (Himanen et al. 2008). Furthermore, temperature induced changes on tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) and devil’s claw (Proboscidea louisianica) were so impactful to the tobacco hornworm (Manduca sexta) that it reversed the widely accepted temperature-size rule, which predicts an increased final mass of ectotherms (e.g insects) at low temperatures (Diamond and Kingsolver 2010).

Plants have acquired tolerance strategies, which may be affected by warmer temperatures. Tolerance minimizes plant fitness costs in response to herbivores, which can be manifested in physiological and developmental traits such as altered photosynthetic ability and regrowth capacity (Bita and Gerats 2013; Mitchell et al. 2016). Photosynthetic activity was reduced in wild parsnip (Pastinaca sativa) following herbivore damage (Zangerl et al. 2002). However, evidence of compensatory photosynthesis in response to defoliation (e.g. in Salix planifolia ssp. planifolia; Houle and Simard 1996) has been noted, but it is not universal. Regrowth capacity or compensatory growth is an adaptive mechanism to stimulate growth in response to biotic and abiotic stresses (e.g. temperature) (Agrawal 2007; Bjorndal et al. 2003; Gong et al. 2015; Liu et al. 2012). Han et al. (2015) reported a reduction in compensatory growth with high-temperature stress. The combined effect of temperature and herbivory on plant tolerance traits are largely unknown (Jamieson et al. 2012).

It is time to dissect the broad predictions of biological population changes under climate warming and delve into the details of how individual species might change and how the interaction of these changes among species might produce new relationships that are not simply linear projections of individual species change. Consideration of this asymmetric change will give a truer picture of what is to come. The purpose of this study was to examine potential asymmetric responses of elevated temperatures on tomato (Solanum lycopersicum var. Better boy) in the presence of an herbivore, Helicoverpa zea that uses this crop as one of its major host plants. First, we hypothesized that elevated temperature affects performance of insect herbivore and host plant differently resulting in an asymmetry. Second, level of salivary defense elicitors in caterpillars is temperature-dependent subsequently affecting plant defense responses. Third, plant- and herbivory (elicitor)-derived changes in host plants in response to elevated temperatures will affect herbivore growth influencing overall insect-plant interactions. In plant, we measured changes in plant growth and leaf phytochemical and morphological traits (leaf defensive proteins; trypsin protease inhibitors (TPI) and polyphenol oxidase (PPO), and leaf trichomes). For the herbivore, we measured larval growth and development as well as activity of the caterpillar salivary defense elicitor, glucose oxidase (GOX). For the interactions between plant and herbivore at different temperatures we compared herbivore growth on damaged and undamaged plants, induction of plant defenses, and tolerance capacity (insect feeding damage recovery and shoot regrowth ability).

Materials and Methods

Temperature Treatments

Growth chambers (Caron, 700X/730X-50/75-X Series) at Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA during 2017–2018 were used for both insects and plants and allocated to three different day/night temperature treatments- i) 25 °C/14 °C (ambient temperature; TA, mean = 19.5 °C), based on the mean temperature in the Mid-Atlantic United States (40.7934° N, 77.8600° W) during the normal tomato growing season (statecollege.com, 2018), ii) 30 °C/18 °C (elevated temperature 1; TE1), and iii) 35 °C/ 22 °C (elevated temperature 2; TE2). The TE1 and TE2 are 4.5 °C above TA and 4.5 °C above TE1 respectively, consistent with the temperature increase expected by the end of this century (Brown and Caldeira 2017). Additionally, TA falls in the below-optimum range for normal tomato growth and production, TE1 is within the optimum range, and TE2 is above-optimum (Hazra et al. 2007). For the insect herbivore (H. zea), the maximum and minimum developmental temperature threshold for larvae are 36 °C and 12.5 °C, respectively (Mangat and Apple 1966; Butler 1976). Thus, TE2 is close to the thermal limit for H. zea, whereas TA and TE1 are within the maximum and minimum threshold range. The experiments were conducted in three temperoral blocks and seedlings were randomly allocated to temperature treatments. Chambers were switched for each block to ensure that the observerved effects were not due to any differences between the chambers.Temperatures inside growth chambers were monitored constantly with a digital thermometer.

Effect of Temperature on Insect Herbivore

Helicoverpa zea eggs were obtained from Benzon Research (Carlisle, PA, USA). H. zea (Family: Noctuidae) is a generalist herbivore, also known as corn earworm or tomato fruit worm, and is a major agricultural pest of a wide variety of crops including tomato (Fitt 1989). For majority of the experiments, neonates were reared individually inside a plastic cup until the end on a wheat gern and casein-based artificial diet (30 ml) (Peiffer and Felton 2005). However, neonates were fed on the tomato leaves for measuring relative growth rates on leaf samples.

Growth and Development

The effect of temperature on larval growth rate, larval duration, pupal duration and pupal mass were evaluated at TA, TE1 and TE2, using 60–70% RH and a photoperiod of 16:8 L:D. Mean larval weights (g) (n = 81–83) were recorded after 5 days. Times to reach pupation from neonate (days) (Larval period) (n = 60–62) and from pupation to adult (days) (pupation period) (n = 60–62) were also recorded. Pupal weights (g) (n = 60–62) were measured 48 h after entering the pupal stage. To ensure high moisture content in the artificial diet, the diet was replaced every two days.

Glucose Oxidase (GOX) Enzyme Assay and Protein Determinations

To evaluate if temperature affects the caterpillar defense elicitor, GOX (enzyme activity and protein amount), H. zea salivary glands (from TA and TE2) were dissected from actively feeding 5th instars (n = 26–29/treatment) (Tian et al. 2012). Glands were homogenized with phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7) and supernatant was collected after centrifugation (4 °C, 7500×g, 10 min) (Eichenseer et al. 1999). The GOX enzyme activity was quantified using a spectrometer at the temperature at which larvae were reared- 25 °C for TA-samples and 35 °C for TE2-samples. Homogenized samples were also used to extract GOX proteins with sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (n = 4). Western blots were blocked using 1:10,000 diluted anti-GOX antibody (Peiffer and Felton 2005). Band intensity on the Western blot gel was quantified using image analysis software (Adobe Photoshop CC 2018 (version 19)). RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis were also conducted as described by Tan et al. (2018). The gox gene expression was tested by qRT-PCR analysis using actin (ACT) as a reference gene. Relative gene expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔct method (n = 5–6) (Livak and Schmittgen 2001).

Effect of Temperature on Host Plants

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum cv Better Boy) seeds were procured commercially (Harris seeds, Rochester, NY, USA). Seedlings were grown in Metromix 400 potting mix (Premier Horticulture, Quakertown, PA, USA) in growth chambers (TA, TE1 and TE2) with a 16 L:8D h photoperiod during 2017–18 until the end of the experiment. Relative humidity (RH) was maintained at 60–70% with photosynthetic active radiation (PAR) of 300 μmol m−2 s−1. A continuous supply of water was provided (every 1–2 days) to ensure that the plants were not water-stressed.

Growth and Development

Roots and shoots of 3-week old plants (n = 8) were separately removed and dried in an oven (60 °C for 48 h) to compare the dry weight (DW) of shoot and root biomass for the three different temperature treatments (TA, TE1 and TE2).

Plant Defense Responses

The activities of two jasmonic acid (JA)-related defensive proteins, PPO and TPI, were measured as a proxy for host plant defense responses against H. zea. PPO and TPI play important roles in enhancing plant defenses in tomato, particularly against H. zea (Broadway and Duffey 1986; Felton et al. 1989; Bhonwong et al. 2009). Two different experiments were conducted to measure the plant-derived and herbivory-derived effects of temperature on plant defense responses.

Plant Derived Effects

Tomato seedlings were grown at three different temperature regimes, whereas H. zea larvae were reared on artificial diet in a common incubator at a constant day/night temperature (TC: 23 °C/19 °C) until placed on experimental plants. At the four-leaf stage, fully expanded terminal leaflets (with and without caterpillar damage) were used as the focal leaves for defensive protein bioassays (Tan et al. 2018). Leaflets were damaged by allowing 5th instar H. zea to completely feed (usually 2–3 h) on leaf tissues inside a clip cage (3.15 cm2), while an empty clip cage was used for the ‘control’ leaflets (terminal). Leaf tissues were sampled from the local leaves. PPO and TPI activities were measured and compared after 48 h of caterpillar damage using a spectrophotometric method (Acevedo et al. 2017). PPO activity was expressed as mOD/min/mg protein; TPI activity was first calculated as TPI (%) = (1-(slope of sample/slope of noninhibitor)) × 100 and then normalized by the protein amount (mg) in the sample (% inhibition/mg protein).

Herbivory (elicitor)-derived effects

H. zea caterpillars were reared on artificial diet under two different day/night temperature regimes, TA (25 °C/14 °C) and TE2 (35 °C/22 °C). Fifth instar larvae were placed on fully expanded terminal leaflets from four-week old tomato plants (n = 10–13) that were grown at a constant temperature and allowed to feed on leaf tissues inside a clip cage (3.15 cm2) under greenhouse conditions (temperature: 27 °C ± 2 °C, humidity: 60–70%, 16 h daylight). PPO and TPI activities were analyzed after 48 h of caterpillar damage as described above to evaluate temperature effects on the ability of herbivory to induce plant defenses. Further, an excised leaf bioassay with 1st instar larvae was conducted for 24 h to test if herbivory (elicitor)-derived changes in plant defense responses influence growth rate of herbivory. Two-days before the bioassay experiment, terminal leaflets from four-week old tomato plants were first mechanically wounded followed by application of 15 μL of salivary gland supernatant from two caterpillar treatments (TA (25 °C/14 °C) and TE2 (35 °C/22 °C)). Supernatant were collected from each caterpillar treatment as described above and was diluted to 1 μg/μL using Bradford assay (Bradford 1976). The ‘control’ leaves were mechanically wounded but did not receive gland supernatant. First-instar H. zea were then allowed to feed on excised leaves from two caterpillar treatments for 24 h and the relative growth rate (RGR) was calculated as:

Where, W1 and W0 are larval weight at days, d0 and d1, and W0 is the initial larval weight before the start of the experiment (Waldbauer 1968).

Density of Leaf Trichomes

Fourteen days post caterpillar feeding, the youngest terminal leaflets were randomly selected from plants (n = 10) from each temperature treatment to compare the density of trichomes on the adaxial leaf surface (Paudel et al. 2019). Both glandular and non-glandular trichomes were counted. Two leaf discs of 0.6-cm diameter were punched out from each side of the mid-vein of a leaflet, and the density (number/cm2) of all glandular and non-glandular trichomes was determined using a light microscope.

Effect of Temperature on Insect-Plant Interactions

Two different strategies, resistance and tolerance, were measured as determinants of insect-plant interactions (Mitchell et al. 2016). Herbivore feeding bioassays were used to measure the plants’ resistance, whereas compensatory photosynthesis and regrowth ability were examined to measure plant tolerance.

Herbivore Feeding Bioassay

Excised leaf bioassays with damaged (D) or undamaged (UD) leaves from three different temperature regimes (TA, TE1 and TE2) were used to measure the temperature effect on host plant quality and resistance to herbivores. The full expanded terminal leaflet from a four-week old tomato plant was damaged by allowing a single 5th instar H. zea to feed inside a clip cage (3.15 cm2), whereas an empty cage was placed on undamaged leaves (control). At 48 h post-damage, randomly selected 1st instars (n = 30) from a stock colony were individually weighed (day 0) and placed into plastic cups (30 ml) with ‘damaged’ and ‘undamaged’ leaves from plants grown under TA, TE1 and TE2-treatments. Individual larvae were then weighed after 48 h and the relative growth rate (RGR) was calculated as described above.

Photosynthesis Rate

Three-week old plants (n = 11) were randomly selected from a group of plants grown in growth chambers under three temperature regimes (TA, TE1 and TE2). The rate of photosynthesis (μmol m−2 s−1) in both damaged and undamaged leaves was repeatedly measured at three different time points, 2 h, 24 h and 120 h post-damage. Fully expanded terminal leaflets were damaged similarly by H. zea larvae as described above. The distal portion of each terminal leaflet (6-cm2 leaf area) was inserted into a cuvette connected to a Li-Cor 6400 (Li-C0r, Lincoln, NE) gas-exchange system with a red/blue LED light source (irradiance of 600 μmol m−2 s−1). The CO2 concentration of the incoming air was adjusted to 400 μmol at a flow rate of 200 μmol m−2 s−1. Output CO2 was measured to determine the rate of photosynthesis as μmol m−2 s−1 (Meyer and Whitlow 1992).

Regrowth Ability (Compensatory Growth)

The shoot tissue above the 2nd mature leaf from 3-week old plants (n = 12) grown under three temperature regimes (TA, TE1 and TE2) were removed mechanically to simulate herbivore (Moreira et al. 2012; Dostálek et al. 2016). Biomass of tissues removed were determined as dry weight (DW; g, 70 °C for 72 h in oven). Plants were then placed back inside respective growth chambers. After 10 days, the shoot regrowth above the 2nd mature leaf was again removed and dry mass was determined. Regrowth percent (%) was calculated as (Van Der Meijden et al. 2000):

Statistical Analyses

Using a completely randomized block design, larval weight gain (g/day), pupal mass (g), developmental time (larval and pupal period in days), GOX enzyme activity, GOX protein determinations (band intensity), gox gene expression, activities of defensive proteins (herbivory-mediated effect), root and shoot biomass (g), and herbivore RGR were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with temperature as the main effect and block as the random effect. Experiments on plant defensive proteins activities (plant-derived effect), trichome density, and herbivore RGR were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA with the main effects being temperature and insect treatment (damaged or undamaged) plus all interaction terms and block as the random effect. Photosynthetic rates (determined at multiple time points) were analyzed with a repeated-measures ANOVA using temperature and treatment (damaged or undamaged leaflets) as independent variables. Generalized linear model with logistic distribution was used to anaylize shoot regrowth (%) data. Means were separated with Tukey’s Honest Significant Differences (HSD) mean comparison tests. Data were checked for normality and analyzed using ‘Minitab 18.0’ software (Minitab Inc. 2018).

Results

Effect of Temperature on Insect Herbivore

Herbivore Growth and Development

There was a significant effect of temperature on H. zea growth when they fed on artificial diet (Fig. 1a). Larval growth increased with elevated temperatures; growth at TE2 (35 °C/ 22 °C) was 2.3-fold and 6.8-fold higher compared to TE1 and TA, respectively. Both the larval and pupal durations were significantly shorter at the highest temperature regime, TE2 (Fig. 1b and c). On average, TE2- caterpillars took 15.05 d and 10 d to complete their larval and pupal stages, whereas TA- caterpillars took 18.6 and 13.5 d, respectively. Pupal weight was significantly lower at TE2 compared to both TE1 and TA (Fig. 1d).

Growth and development of H. zea reared on artificial diets at three different day/night temperatures: 25 °C/14 °C (ambient temperature; TA-caterpillars), 30 °C/18 °C (elevated temperature 1; TE1-caterpillars) and 35 °C/ 22 °C (elevated temperature 2; TE2-caterpillars). a) Mean larval weight gain (g/day) calculated by dividing the weight of the larvae after 5 d by the number of days (n) b) Larval period calculated by counting number of days (n) from neonate to pupa c) Pupal period calculated by counting number of days (n) from pupation to adult, and d) Mean pupal weight (g). Bars are mean ± SEM and means with different letters are statistically different as determined by a Tukey HSD. There was significant effect of temperature on larval weight gain (F = 1003, df = 2, P < 0.001), larval period (F = 250.1, df = 2, P < 0.001), pupal period (F = 345.5, df = 2, P < 0.001), and pupal weight gain (F = 230.84, df = 2, P < 0.001)

Glucose Oxidase (GOX) Enzyme Assay and Protein Determinations

Temperature had a significant effect on the activity of GOX in the labial salivary glands of H. zea caterpillars (Fig. 2a). TA-caterpillars had 1.2-fold higher GOX activity than the TE2-treated caterpillars. This result was further confirmed by the immunoblot analyses, where a reduction in GOX protein accumulation in the labial glands of larvae reared at TE2 compared to TA was observed (Fig. 2b). However, there was no significant difference in the transcript level of gene encoding gox (Fig. 2c).

Glucose oxidase (GOX) enzyme activity and transcript levels in labial salivary glands of 5th instar H. zea reared at two different day/night temperatures: 25 °C/14 °C (ambient temperature; TA-caterpillars) and 35 °C/ 22 °C (elevated temperature 2; TE2-caterpillars). a) GOX enzyme activity (mOD/min/mg protein) b) Absolute intensity of bands from immunoblot analysis of glucose oxidase (GOX) protein, and c) Relative expression of gox transcript levels. Caterpillars were reared on artificial diet post-hatching. Bars are mean ± SEM and means with different letters are statistically different as determined by a Tukey HSD. There was a significant effect of temperature on GOX enzyme activity (F = 8.5, df = 1, P < 0.001) and band intensity (F = 8.0, df = 1, P < 0.05), but not on H. zea gox transcript level (F = 0.7, df = 1, P = 0.15)

Effect of Temperature on Host Plants

Growth and Development

Temperature had a significant effect on both shoot and root biomass of tomato plants (Fig. 3a and b). With elevated temperature (TE1), root and shoot biomass was increased but declined with TE2. On average, TE1-plants had 1.3-fold and 2.4-fold higher shoot biomass, and 1.5-fold and 2-fold higher root biomass than those grown at TA and TE2, respectively.

Growth and development of tomato plants, a) Shoot biomass (dry weight (g)) and b) root biomass (dry weight (g)) of three-week old plants grown at three different day/night temperatures: 25 °C/14 °C (ambient temperature; TA-plants), 30 °C/18 °C (elevated temperature 1; TE1-plants) and 35 °C/ 22 °C (elevated temperature 2; TE2-plants). Bars are mean ± SEM and means with different letters are statistically different as determined by a Tukey HSD. Temperature had a significant effect on both shoot (F = 209.7, df = 2, P < 0.001) and root biomass (F = 131.7, df = 2, P < 0.001)

Plant Defense Responses

Plant-Derived Effects

Trypsin Protease Inhibitor

Activity of TPI in leaves was significantly affected by both temperature and insect damage (Fig. 4a). In both undamaged and damaged leaves, the TPI activity in TE1-plants was highest. While TE2-plants had the lowest activity of TPI in undamaged leaves, they had the highest percent (%) induction (17-fold increase) followed byTE1 (8.5-fold increase) and TA (7-fold increase) in response to caterpillar damage.

Activity of defensive proteins: a) Trypsin protease inhibitor (TPI; mOD/min/mg protein) and b) Polyphenol oxidase (PPO; % inhibition/mg protein) activity in undamaged and damaged leaves from four-leaf stage plants grown at three different day/night temperature: 25 °C/14 °C (ambient temperature; TA-plants), 30 °C/18 °C (elevated temperature 1; TE1-plants) and 35 °C/ 22 °C (elevated temperature 2; TE2-plants). Fifth-instar H. zea, reared at a common day/night temperature (TC: 23 °C/19 °C) were used to damage leaves. Bars are mean ± SEM and means with different letters are statistically different as determined by a Tukey HSD, P < 0.05. There were significant temperature (PPO; F = 147.6, df = 2, P < 0.001,TPI: F = 357.5, df = 2, P < 0.001), insect damage (PPO: F = 1150.6, df = 1, P < 0.001, TPI: F = 5741.3, df = 1, P < 0.001), and interactive effects of temperature and insect damage (PPO: F = 70.8, df = 2, P < 0.001, TPI: F = 209.4, df = 2, P < 0.001) on PPO and TPI activities

Polyphenol Oxidase (PPO)

There were significant effects of temperature and insect feeding on PPO activity (Fig. 4b). Compared to both TA and TE2, plants grown at TE1 had significantly higher PPO activity in both damaged and undamaged leaves. In contrast, percent (%) induction of PPO following larval damage was highest at TE2 (3.5-fold increase), followed by TA (2.5-fold increase) and TE1 (2.3-fold increase).

Herbivory (Elicitor)-Derived Effects

When fed on leaves from plants grown at a common temperature (TC), caterpillars reared under a warmer temperature (TE2) induced significantly lower levels of both TPI and PPO activities in plants (Fig. 5a and b). On average, the activity of PPO and TPI was 1.1-fold and 1.6-fold higher, respectively, in the leaves damaged by TA-caterpillars compared to TE2-caterpillars.

Activity of defensive proteins: a) Trypsin protease inhibitor (TPI; mOD/min/mg protein) and b) Polyphenol oxidase (PPO; % inhibition/mg protein) activity in leaves damaged by 5th instar H. zea, which were reared at two different temperature regimes: 25 °C/14 °C (ambient temperature; TA-caterpillars) and 35 °C/ 22 °C (elevated temperature 2; TE2-caterpillars). Control plants didn’t receive any herbivore treatment. Plants were grown in a common greenhouse environment. Caterpillars were reared on artificial diet until placed on experimental leaves. Bars are mean ± SEM and means with different letters are statistically different as determined by a Tukey HSD. There was a significant effect of caterpillar rearing temperature on PPO (F = 169.9, df = 1, P < 0.001) and TPI (F = 153.1, df = 1, P < 0.001) activities

In addition, the growth rate of caterpillars was significantly higher when fed on leaves treated with salivary gland homogenate from TE2-caterpillars compared to those from TA-caterpillars (Fig. 6).

Relative growth rate (RGR) (mass gained((mg)/g/day)) of 1st instar H. zea fed on detached leaves to which salivary gland homogenate was added from 5th instar H. zea reared at two different temperature regimes: 25 °C/14 °C (ambient temperature; TA-caterpillars) and 35 °C/ 22 °C (elevated temperature 2; TE2-caterpillars). Gland homogenate was applied 2 d prior to collecting leaves for bioassays. Tomato plants were grown in a common greenhouse environment. Caterpillars were reared on artificial diet. Bars are mean ± SEM and means with different letters are statistically different as determined by a Tukey HSD (F = 6.6, df = 1, P < 0.05)

Density of Leaf Trichomes

Temperature and insect damage each had a significant effect on leaf trichome densities, but there was no significant interaction (Fig. 7). In both damaged and undamaged leaves, the density of leaf trichomes increased at warmer temperatures. On average, TE2-plants had a 1.5 and 2-fold higher trichome density in undamaged leaves and and a 1.47 and 1.41-fold higher trichome density in damaged leaves compared to TE1 and TA-plants respectively. Post-insect damage, a significant induction of trichomes was only noted in TE2-plants.

Density of glandular and non-glandular trichomes (number of trichomes/cm2) on undamaged (UD) and damaged (D) leaf surface (adaxial) at three different day/night temperatures: 25 °C/14 °C (ambient temperature; TA-plants), 30 °C/18 °C (elevated temperature 1; TE1-plants) and 35 °C/ 22 °C (elevated temperature 2; TE2-plants). Fifth-instar H. zea, reared at a common day/night temperature (TC: 23 °C/19 °C) were used to damage leaves; trichomes on damaged and undamaged leaves were counted 14 d post-damage. Bars are mean ± SEM and means with different letters are statistically different as determined by a Tukey HSD. Differences are between ‘damaged’ and ‘undamaged’ leaves within temperature. Both temperature (F = 159.2, df = 2, P < 0.001) and insect damage (F = 19.3, df = 1, P < 0.001) had significant effects on the density of leaf trichomes. There was no interactive effect of temperature and insect damage (F = 1.15, df = 2, P = 0.324)

Effect of Temperature on Insect-Plant Interactions

Herbivore Feeding Bioassay

There was a significant effect of temperature and previous insect damage on herbivore growth (Fig. 8). The relative growth rate (RGR) of larvae was lowest on undamaged leaves from TA-plants, followed by TE1- and TE2-plants. However, the percent reduction in growth was comparatively higher on damaged leaves from TE2-plants. On average, RGR was reduced by 1.4-fold, 1.2-fold, and 1.16-fold on damaged leaves compared to undamaged leaves from plants grown under TE2, TA, and TE1 regimes, respectively.

Effect of temperature on relative growth rate (RGR) (mass gained((mg)/g/day)) of 1st instar H. zea fed on detached leaves (damaged or undamaged) from plants grown at three different day/night temperatures: 25 °C/14 °C (ambient temperature; TA-plants + caterpillars), 30 °C/18 °C (elevated temperature 1; TE1- plants + caterpillars) and 35 °C/ 22 °C (elevated temperature 2; TE2- plants + caterpillars). Insects and leaves were placed in a bioassay cup and placed inside respective growth chambers during the experiment. Fifth instar H. zea, reared at a common day/night temperature (CT: 23 °C/19 °C) were used to damage leaves and the bioassay was conducted 48 h post-damage. Bars are mean ± SEM and means with different letters are statistically different as determined by a Tukey HSD. There was a significant independent and interactive effect of temperature and insect damage on herbivore growth (temperature: F = 161.4, df = 2, P < 0.001; insect damage: F = 188.5, df = 1, P < 0.001; temperature× insect damage: F = 43.0, df = 2, P < 0.001)

Photosynthesis Rate

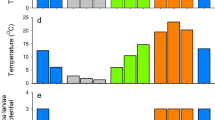

Temperature and insect damage significantly affected leaves’ photosynthetic rates, and the recovery of photosynthetic capacity after herbivore damage varied with time (Fig. 9). In both damaged and undamaged control leaves, photosynthetic rate was highest in TE1-plants followed by TA- and TE2-plants. In damaged leaves, photosynthesis remained consistently lower compared to undamaged controls throughout the experiment, but varied greatly among temperature treatments. Post-hoc results are presented in Supporting Information Table S1.

Rate of photosynthesis (μmolm−2 s−1) in undamaged (control) and damaged (by H. zea) leaves (treatment) at 2 h, 48 h and 120 h post-feeding periods at three different day/night temperatures: 25 °C/14 °C (ambient temperature; TA-plants), 30 °C/18 °C (elevated temperature 1; TE1-plants) and 35 °C/ 22 °C (elevated temperature 2; TE2-plants). Fifth instar H. zea, reared at a common day/night temperature (TC: 23 °C/19 °C), were used to damage leaves. Bars are mean ± SEM and different letters indicates a statistically difference. There was a significant effect of temperature (F = 998.9, df = 2, P < 0.001), insect damage (F = 305.6, df = 1, P < 0.001) and time (F = 20.2, df = 1, P < 0.001) on photosynthetic rates of leaves. Two-way interactive effects were also significantly different (temperature × time: F = 4.4, df = 4, P < 0.005; temperature × insect damage: F = 14.8, df = 2, P < 0.001; time × insect damage: F = 31.3, df = 2, P < 0.001)

Recovery of photosynthetic rate post herbivore damage varied with time and temperature treatments. At 2 h post insect damage, photosynthetic rate in damaged leaves was reduced by 31.0%, 11.5%, and 43.1% compared to the undamaged control leaves from TA-, TE2- and TE2-plants, respectively. Within temperature treatments, photosynthesis after insect damage was most inhibited in leaves from TE2-plants (% reduction in photosynthetic rate- 2 h/48 h/120 h; 43.1%/27.3%/19.6%), with a drastic reduction immediately after damage; these plants failed to recover to the level of the control rate until 120 h post-damage. Photosynthetic activity of leaves from the TA-plants was also affected strongly by insect feeding; however, it recovered to some extent during the post-damage period (% reduction in photosynthetic rate- 2 h/48 h/120 h; 31.0%/18.5%/5.3%). Photosynthesis on leaves from TE1-plants was least affected 2 h after damage (11.5%) and recovered to a greater extent at 120 h post-damage (% reduction in photosynthetic rate- 48 h/120 h; 8.8%/4.0%).

Regrowth Ability (Compensatory Growth)

Temperature affected the rate of shoot regrowth (Fig. 10). On average, the regrowth percentage (%) for TE1-plants was 1.7-fold and 2.2-fold higher than for TA- and TE2-plants, respectively. TE2-plants showed considerably less capacity to compensate for shoot loss.

Shoot regrowth (%) of plants grown at three different day/night temperatures: 25 °C/14 °C (ambient temperature; TA-plants), 30 °C/18 °C (elevated temperature 1; TE1-plants) and 35 °C/ 22 °C (elevated temperature 2; TE2-plants). Bars are mean ± SEM and means with different letters are statistically different as determined by a Tukey HSD. Temperature significantly affected the rate of shoot regrowth (F = 408.38, df = 2, P < 0.001)

Discussion

Temperature is one of the most important abiotic factors affecting both insects and plants. Temperatures are projected to increase around the globe for the foreseeable future. However, predicting the impacts of temperature change in an ecological system is complex because the response of individual species may be asymmetric. Each organism in the system may react differently to temperature change, and the interaction of species may alter responses of the individual species in an asymmetric manner. The asymmetry will produce new relationships among species, further complication predictions. In our tomato/herbivore system we found an asymmetric effect of elevated temperature on insects and plants, which consequently altered overall herbivore-plant interactions. Patterns of variation included differences in insect and plant growth, production of herbivore salivary elicitors, plant defensive protein activities and their inducibility, leaf trichome density, impacts on herbivore growth rates and plants’ tolerance ability. The effect of temperature on a plant defense elicitor, GOX, has not been previously reported.

The growth rate of an insect herbivore, H. zea, was accelerated with elevated temperatures when fed on an artificial diet. This is consistent with the prediction that, within physiological limits, temperature increase accelerates insect growth (Bale et al. 2002; Berggren et al. 2009). For H. zea, maximum and minimum temperature threshold are 12.5 °C and 36 °C respectively (Butler 1976; Mangat and Apple 1966). Higher larval weight is positively correlated with fecundity (Honěk 1993), whereas accelerated growth increases the number of generations per year, thus, reducing the window of vulnerability of the herbivore to predators and pathogens (Jaworski and Hilszczański 2013). In contrast to larval weight, pupal weight was reduced at higher temperatures (Atkinson 1994). A negative correlation between accelerated larval growth rate and pupal mass has also been demonstrated in the Monarch caterpillar (Danaus plexippus) (York and Oberhauser 2002) and tobacco hornworm (Manduca sexta) (Kingsolver 2007).

Amounts of the salivary defense elicitor GOX were significantly higher in caterpillars reared at low temperatures compared to a warmer temperature. A reduced level of GOX in caterpillars reared at a warmer temperature may be a result of a tradeoff between the investment in body size and immunity at higher temperatures (Triggs and Knell 2012). Changing nutritional demand at higher temperatures may have also negatively affected the level of salivary elictor production (Hu et al. 2008; Lee et al. 2015). Interestingly, while gox gene expression was not significantly different among larvae grown at different temperatures, a higher level of GOX protein was observed in TA-caterpillars. Transcript levels (mRNA) are generally a good indicator of enzyme expression, however, there are various post-transcriptional processes (e.g., increased protein half-life) that are important to the final synthesis of a protein, which might have affected the correlation (Maier et al. 2009). While correlations between salivary defense elicitor protein levels and temperature have not been previously reported, there are studies on the effect of temperature on immune-related enzymes (Ouedraogo et al. 2003; Adamo and Lovett 2011; Perry 2017). For example, Adamo and Lovett (2011) found increased activity of two immune-related enzymes, phenoloxidase and lysosome-like enzymes in the cricket (Gryllus texensis) when the temperature was enhanced by 7 °C above average field temperature (26 °C). In contrast, Perry (2017) reported weakened immune functions at a warmer temperature (28.5 °C compared to 21.5 °C) in Drosophila (Drosophila melanogaster). It should be noted that GOX, besides its role in induction of plant defenses, also plays a role in cellular immunity (Musser et al. 2005).

Temperature influenced plant defense responses- a) by impacting temperature-sensitive plant defensive traits (plant-derived) and b) through temperature-induced changes in the ability of caterpillars to elicit plant defensive proteins (herbivory-derived). Further, the plant-derived effects varied between undamaged and damaged leaves. In undamaged leaves, constitutive defensive enzyme activities increased initially with increases in temperature, but were significantly reduced at the highest temperature regime. A similar result was reported for broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica) where seedlings grown at a comparable temperature (30/15 °C: day/night) to our experiment had significantly higher glucosinolate (GS) levels compared to those grown at lower temperatures (22/15 °C and 18/12 °C) (Pereira et al. 2002). Rivero et al. (2003) also reported a reduced level of PPO and POX activities in tomatoes at a warmer temperature of 35 °C. In contrast, in response to herbivory damage, the percent induction of defensive enzymes was highest in leaves grown at the highest temperature (TE2- plants). While very little information exists on the effect of elevated temperature on induction of plant defenses (Bidart-Bouzat and Imeh-Nathaniel 2008), a few studies have reported a higher induction of defensive enzymes in response to other environmental stressors. For example, there was significant induction in Arabidopsis thaliana of GS in response to insect feeding under drought stress and elevated C02 (Bidart-Bouzat et al. 2005). Interestingly, induction of defensive proteins, in addition to the plant-derived effects, were also affected by changes in GOX in the herbivore; a low level of induced defensive proteins in plants was coupled with a reduced level of GOX in caterpillars reared at an elevated temperature (Tian et al. 2012). The overall implications of elevated temperature on plant defense responses should, therefore, reflect a composite effect of both plant and herbivory-derived effects.

When H. zea fed on tomato leaves, growth rate varied with temperature and was further affected by feeding on damaged versus undamaged leaves. Elevated temperatures accelerated H. zea growth on undamaged leaves (Gillooly et al. 2001; O’Connor et al. 2011). A similar finding was reported by Lemoine et al. (2014), where most herbivores (from 21 herbivore-plant pairs) from three orders (Lepidoptera, Coleoptera, Hymenoptera) demonstrated a higher consumption rate within a range of average temperatures of 20 °C and 30 °C. In contrast, larval growth in damaged leaves yielded a variable response; the larval growth rate increased at TE1 -temperature, however, it was reduced at the highest temperature regime (TE2). The percent reduction in larval growth rate between undamaged vs damaged leaves was also highest on leaves grown under the highest temperature regime, which indicated that TE2-plants elicited higher levels of resistance once attacked, which in turn, negatively influenced herbivore performance. Higher inducibility of PPO and TPI in TE2-plants may have contributed partly to a higher resistance against H. zea larvae. Previous reports have shown strong larval growth inhibition with induction of PPO and TPI (Duffey and Stout 1996; Felton et al. 1989; War et al. 2012). The variation in insects’ response to undamaged and damaged leaves illustrated the importance of induced resistance when estimating the impact of environmental changes on insect-plant interactions. Interestingly, higher leaf trichome densities at warmer temperatures failed to affect herbivore growth; therefore, trichomes in our system may play a physiological role to help plants adapt to temperature stress instead (Bickford 2016; Xiao et al. 2017). Additionally, leaf trichomes in tomatoes have been found to offer resistance mostly against small insects such as whiteflies (Bleeker et al. 2009; Firdaus et al. 2012), leafhoppers (Dellinger et al. 2006; Kaplan et al. 2009) and mites (Maluf et al. 2007).

The ability of a plant to tolerate stresses was compromised at the highest temperature regime (TE2) as measured by the growth, photosynthesis recovery and regrowth ability, whereas plant grown at the TE1 regime were the most tolerant. For tomatoes, the TE1- temperature regime corresponds to an optimum temperature range for growth and production, whereas TE2 is above-optimum (Berggren et al. 2009; Hazra et al. 2007;). Reduced vegetative growth of plants may also affect reproductive success due to limited energy reserves (Sumesh et al. 2008). A decline in photosynthetic activity (Sharkey and Zhang 2010; Todorov et al. 2003) and regrowth ability (Han et al. 2015) with above-optimum temperatures has been previously reported. However, other reports found no evidence of compensatory photosynthesis and growth responses to herbivory and mechanical damage, respectively (Han et al. 2015; Retuerto et al. 2004; Strauss and Agrawal 1999).

Within the experimental temperature range, our study revealed that insects are differentially sensitive compared to their host plants based on a phenotypic response (growth); insect growth was accelerated in both TE1 and TE2-temperature regimes, whereas, plant growth was increased initially (TE1) but reduced significantly at TE2 (Fig. 11a). This may disrupt phenological synchrony affecting insect herbivore populations (Renner and Zohner 2018). For example, insects like Japanese beetles (Popilia japonica) may emerge earlier than their hosts (soybean and corn) as a result of climate warming, and therefore, have to feed on low quality foliage negatively affecting herbivore fitness (Delucia et al. 2012). Similarly, competitive relationships among herbivores may also depend on temperature, as was shown with two aphid vector species of barley yellow dwarf virus (Porras et al. 2018).

Graphical illustrations of major findings a) Within the experimental temperature range, when insects and plants were reared and grown independently, growth of insect herbivores continued to rise with temperature (red line), whereas tomato growth increased initially and declined at the highest temperature (green line) b) Temperature altered induced plant defense by influencing level of caterpillar plant defense elicitor, GOX (herbivory-derived); Activity of GOX was reduced at a warmer temperature c) Consitutive level of plant defensive proteins increased initially but declined with elevated temperature (blue line). Inducibility (induced/constitutive) of plant defensive proteins, however, was highest in plants grown at highest temperature regime d) When tomato plants were exposed simultaneously to temperature and herbivore treatment, plant resistance mechanisms were enhanced resulting in reduced herbivore growth (blue line) e) Plants’ tolerance to temperature and herbivory stress as measured by photosynthesis recovery rate and shoot regrowth increased significantly initially but declined at the highest temperature

A novel finding that salivary elicitors of induced plant defenses in caterpillars is regulated by temperature is also reported here. Temperature change not only influenced the insect’s metabolic activity but also its capacity to manipulate plant defenses (Fig. 11b). Future studies are warranted to determine the adaptive ability of herbivores to respond to changes in temperature by altering the level of plant elicitors. Inducibility of plant defenses to insect herbivory was highest in plants grown at above-optimum temperatures (TE1) and larval growth response varied between previously damaged and undamaged leaves (Fig. 11c and d). Some of these induced effects persist over an entire season, therefore, may have a significant impact on overall crop losses (Paudel et al. 2014; Strapasson et al. 2014). This emphasizes the importance of induced resistance to estimate the impact of climatic change on insect-plant interactions (Paudel et al. 2019), which has generally been overlooked in past studies. In contrast to plants’ resistance, tolerance ability as measured by the photosynthesis recovery rate and shoot regrowth increased initially but was compromised at the above-optimum temperatures (TE2) (Fig. 11e).

Elevated temperature thus produced an asymmetric effect between an herbivore and its host plant, illustrating the complexity of changes in insect-plant interactions that could result as the climate warms. In theory, while activity of insect herbivores is expected to increase with global warming, independent and interactive changes in insect and plant traits as demonstrated by our results will determine the amount of crop losses. Therefore, the potential developmental plasticity of insects and plants in coping with environmental changes as well as a transformation of the interactions between them will determine species distribution and community structure. Predicitions of the future under climate change that do not take this complexity into consideration will be unconvincing.

References

Acevedo FE, Peiffer M, Tan CW, Stanley BA, Stanley A, Wang J, Jones AG, Hoover K, Rosa C, Luthe D, Felton G (2017) Fall armyworm-associated gut bacteria modulate plant defense responses. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact 30(2):127–137

Adamo SA, Lovett MM (2011) Some like it hot: the effects of climate change on reproduction, immune function and disease resistance in the cricket Gryllus texensis. J Exp Biol 214(12):1997–2004

Agrawal AA (2007) Macroevolution of plant defense strategies. Trends in ecology and evolution 22(2):103–109

Angilletta Jr, M. J., and Angilletta, M. J. (2009). Thermal adaptation: a theoretical and empirical synthesis. Oxford University Press

Atkinson D (1994) Temperature and organism size: a biological law for ectotherms? Adv Ecol Res 25:1–58

Atkinson NJ, Urwin PE (2012) The interaction of plant biotic and abiotic stresses: from genes to the field. J Exp Botany 63(10):3523–3543

Bale JS, Masters GJ, Hodkinson ID, Awmack C, Bezemer TM, Brown VK et al (2002) Herbivory in global climate change research: direct effects of rising temperature on insect herbivores. Glob Chang Biol 8(1):1–16

Bauerfeind SS, Fischer K (2013) Increased temperature reduces herbivore host-plant quality. Glob Chang Biol 19(11):3272–3282

Berggren Å, Björkman C, Bylund H, Ayres MP (2009) The distribution and abundance of animal populations in a climate of uncertainty. Oikos 118(8):1121–1126

Bhonwong A, Stout MJ, Attajarusit J, Tantasawat P (2009) Defensive role of tomato polyphenol oxidases against cotton bollworm (Helicoverpa armigera) and beet armyworm (Spodoptera exigua). J Chem Ecol 35(1):28–38

Bickford CP (2016) Ecophysiology of leaf trichomes. Functional Plant Biol 43(9):807–814

Bidart-Bouzat MG, Imeh-Nathaniel A (2008) Global change effects on plant chemical defenses against insect herbivores. J Integrative Plant Biol 50(11):1339–1354

Bidart-Bouzat MG, Mithen R, Berenbaum MR (2005) Elevated CO2 influences herbivory-induced defense responses of Arabidopsis thaliana. Oecologia 145(3):415–424

Bita C, Gerats T (2013) Plant tolerance to high temperature in a changing environment: scientific fundamentals and production of heat stress-tolerant crops. Frontiers Plant Sci 4:273

Bjorndal KA, Bolten AB, Dellinger T, Delgado C, Martins HR (2003) Compensatory growth in oceanic loggerhead sea turtles: response to a stochastic environment. Ecology 84(5):1237–1249

Bleeker PM, Diergaarde PJ, Ament K, Guerra J, Weidner M, Schütz S, de Both MTJ, Haring MA, Schuurink RC (2009) The role of specific tomato volatiles in tomato-whitefly interaction. Plant Physiol 151(2):925–935

Bradfield M, Stamp N (2004) Effect of nighttime temperature on tomato plant defensive chemistry. J Chem Ecol 30(9):1713–1721

Bradford MM (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72(1–2):248–254

Broadway RM, Duffey SS (1986) Plant proteinase inhibitors: mechanism of action and effect on the growth and digestive physiology of larval Heliothis zea and Spodoptera exiqua. J Insect Physiol 32(10):827–833

Brown PT, Caldeira K (2017) Greater future global warming inferred from Earth’s recent energy budget. Nature 552(7683):45–50

Butler GD Jr (1976) Bollworm: development in relation to temperature and larval food. Env Entomol 5(3):520–522

Dellinger TA, Youngman RR, Laub CA, Brewster CC, Kuhar TP (2006) Yield and forage quality of glandular-haired alfalfa under alfalfa weevil (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) and potato leafhopper (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) pest pressure in Virginia. J Econ Entomol 99(4):1235–1244

DeLucia EH, Nabity PD, Zavala JA, Berenbaum MR (2012) Climate change: resetting plant-insect interactions. Plant Physiol 160(4):1677–1685

Deutsch CA, Tewksbury JJ, Tigchelaar M, Battisti DS, Merrill SC, Huey RB, Naylor RL (2018) Increase in crop losses to insect pests in a warming climate. Science 361(6405):916–919

Diamond SE, Kingsolver JG (2010) Fitness consequences of host plant choice: a field experiment. Oikos 119(3):542–550

Dostálek T, Rokaya MB, Maršík P, Rezek J, Skuhrovec J, Pavela R, Münzbergová Z (2016) Trade-off among different anti-herbivore defence strategies along an altitudinal gradient. AoB plants 8

Duffey SS, Stout MJ (1996) Antinutritive and toxic components of plant defense against insects. Archives of Insect Biochem Physiol 32(1):3–37

Ehleringer JR, Mooney HA (1978) Leaf hairs: effects on physiological activity and adaptive value to a desert shrub. Oecologia 37(2):183–200

Eichenseer H, Mathews MC, Bi JL, Murphy JB, Felton GW (1999) Salivary glucose oxidase: multifunctional roles for Helicoverpa zea? Arch Insect Biochem Physiol 42(1):99–109

Felton GW, Donato K, Del Vecchio RJ, Duffey SS (1989) Activation of plant foliar oxidases by insect feeding reduces nutritive quality of foliage for noctuid herbivores. J Chem Ecol 15(12):2667–2694

Field, C. B. (Ed.). (2014). Climate change 2014–impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: regional aspects. Cambridge University Press

Firdaus S, van Heusden AW, Hidayati N, Supena EDJ, Visser RG, Vosman B (2012) Resistance to Bemisia tabaci in tomato wild relatives. Euphytica 187(1):31–45

Fitt GP (1989) The ecology of Heliothis species in relation to agroecosystems. Annu Rev Entomol 34(1):17–53

Gillooly JF, Brown JH, West GB, Savage VM, Charnov EL (2001) Effects of size and temperature on metabolic rate. Science 293(5538):2248–2251

Gong XY, Fanselow N, Dittert K, Taube F, Lin S (2015) Response of primary production and biomass allocation to nitrogen and water supplementation along a grazing intensity gradient in semiarid grassland. Eur J Agron 63:27–35

Green TR, Ryan CA (1973) Wound-induced proteinase inhibitor in tomato leaves: some effects of light and temperature on the wound response. Plant Physiol 51(1):19–21

Han H, Tian Z, Fan Y, Cui Y, Cai J, Jiang D, Cao W, Dai T (2015) Water-deficit treatment followed by re-watering stimulates seminal root growth associated with hormone balance and photosynthesis in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seedlings. Plant Growth Regul 77(2):201–210

Hatfield JL, Prueger JH (2015) Temperature extremes: effect on plant growth and development. Weather Climate Extremes 10:4–10

Hazra P, Samsul HA, Sikder D, Peter KV (2007) Breeding tomato (Lycopersicon Esculentum mill) resistant to high temperature stress. Internat J Plant Breeding 1(1):31–40

Himanen SJ, Nissinen A, DONG WX, NERG AM, Stewart CN Jr, Poppy GM, Holopainen JK (2008) Interactions of elevated carbon dioxide and temperature with aphid feeding on transgenic oilseed rape: are Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) plants more susceptible to nontarget herbivores in future climate? Glob Chang Biol 14(6):1437–1454

Honěk A (1993) Intraspecific variation in body size and fecundity in insects: a general relationship. Oikos 66:483–492

Houle G, Simard G (1996) Additive effects of genotype, nutrient availability and type of tissue damage on the compensatory response of Salix planifolia ssp. planifolia to simulated herbivory. Oecologia 107(3):373–378

Hu YH, Leung DW, Kang L, Wang CZ (2008) Diet factors responsible for the change of the glucose oxidase activity in labial salivary glands of Helicoverpa armigera. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol 68(2):113–121

Jamieson MA, Burkle LA, Manson JS, Runyon JB, Trowbridge AM, Zientek J (2017) Global change effects on plant–insect interactions: the role of phytochemistry. Curr Opinion Insect Sci 23:70–80

Jamieson MA, Trowbridge AM, Raffa KF, Lindroth RL (2012) Consequences of climate warming and altered precipitation patterns for plant-insect and multitrophic interactions. Plant Physiol 160(4):1719–1727

Jaworski T, Hilszczański J (2013) The effect of temperature and humidity changes on insects development their impact on forest ecosystems in the expected climate change. Forest Res Papers 74(4):345–355

Kaplan I, Dively GP, Denno RF (2009) The costs of anti-herbivore defense traits in agricultural crop plants: a case study involving leafhoppers and trichomes. Ecol Appl 19(4):864–872

Kingsolver JG (2007) Variation in growth and instar number in field and laboratory Manduca sexta. Proc Royal Soc B: Biol Sci 274(1612):977–981

Lee KP, Jang T, Ravzanaadii N, Rho MS (2015) Macronutrient balance modulates the temperature-size rule in an ectotherm. American Natur 186(2):212–222

Lemoine NP, Shantz AA (2016) Increased temperature causes protein limitation by reducing the efficiency of nitrogen digestion in the ectothermic herbivore Spodoptera exigua. Physiol Entom 41(2):143–151

Lemoine NP, Burkepile DE, Parker JD (2014) Variable effects of temperature on insect herbivory. PeerJ 2:e376

Liu J, Wang L, Wang D, Bonser SP, Sun F, Zhou Y, Gao Y, Teng X (2012) Plants can benefit from herbivory: stimulatory effects of sheep saliva on growth of Leymus chinensis. PLoS One 7(1):e29259

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2− ΔΔCT method. Methods 25(4):402–408

Maier T, Güell M, Serrano L (2009) Correlation of mRNA and protein in complex biological samples. FEBS Lett 583(24):3966–3973

Maluf WR, Inoue IF, Ferreira RDPD, Gomes LAA, Castro EMD, Cardoso MDG (2007) Higher glandular trichome density in tomato leaflets and repellence to spider mites. Pesq Agrop Brasileira 42(9):1227–1235

Mangat BS, Apple JW (1966) Induction of diapause in the corn earworm, Heliothis zea (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Ann Entomol Soc America 59(5):1014–1015

Meyer GA, Whitlow TH (1992) Effects of leaf and sap feeding insects on photosynthetic rates of goldenrod. Oecologia 92(4):480–489

Minitab (Version 18) [Software] 2018. Available from: http://www.minitab.com/en-US/products/minitab/default.aspx. Accessed 12 Aug 2018

Mitchell C, Brennan RM, Graham J, Karley AJ (2016) Plant defense against herbivorous pests: exploiting resistance and tolerance traits for sustainable crop protection. Frontiers Plant Sci 7:1132

Moreira X, Zas R, Sampedro L (2012) Quantitative comparison of chemical, biological and mechanical induction of secondary compounds in Pinus pinaster seedlings. Trees 26(2):677–683

Musser RO, Cipollini DF, Hum-Musser SM, Williams SA, Brown JK, Felton GW (2005) Evidence that the caterpillar salivary enzyme glucose oxidase provides herbivore offense in solanaceous plants. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol 58(2):128–137

Musser RO, Hum-Musser SM, Eichenseer H, Peiffer M, Ervin G, Murphy JB, Felton GW (2002) Herbivory: caterpillar saliva beats plant defences. Nature 416(6881):599–600

O’Connor MI, Gilbert B, Brown CJ (2011) Theoretical predictions for how temperature affects the dynamics of interacting herbivores and plants. American Nat 178(5):626–638

Orozco-Cárdenas ML, Narváez-Vásquez J, Ryan CA (2001) Hydrogen peroxide acts as a second messenger for the induction of defense genes in tomato plants in response to wounding, systemin, and methyl jasmonate. Plant Cell 13(1):179–191

Ouedraogo RM, Cusson M, Goettel MS, Brodeur J (2003) Inhibition of fungal growth in thermoregulating locusts, Locusta migratoria, infected by the fungus Metarhizium anisopliae var acridum. J Invert Pathol 82(2):103–109

Paudel S, Lin PA, Foolad MR, Ali JG, Rajotte EG, Felton GW (2019) Induced plant defenses against Herbivory in cultivated and wild tomato. J Chem Ecol 45(8):693–707

Paudel S, Rajotte EG, Felton GW (2014) Benefits and costs of tomato seed treatment with plant defense elicitors for insect resistance. Arthropod-Plant Inter 8(6):539–545

Peiffer M, Felton GW (2005) The host plant as a factor in the synthesis and secretion of salivary glucose oxidase in larval Helicoverpa zea. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol 58(2):106–113

Pereira FMV, Rosa E, Fahey JW, Stephenson KK, Carvalho R, Aires A (2002) Influence of temperature and ontogeny on the levels of glucosinolates in broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica) sprouts and their effect on the induction of mammalian phase 2 enzymes. J Agric Food Chem 50(21):6239–6244

Pérez-Estrada LB, Cano-Santana Z, Oyama K (2000) Variation in leaf trichomes of Wigandia urens: environmental factors and physiological consequences. Tree Physiol 20(9):629–632

Perry, D. (2017). Climate change and the evolution of insect immune function. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Central Florida

Porras M, De Moraes CM, Mescher MC, Rajotte EG, Carlo TA (2018) A plant virus (BYDV) promotes trophic facilitation in aphids on wheat. Sci Rep 8(1):11709

Renner SS, Zohner CM (2018) Climate change and phenological mismatch in trophic interactions among plants, insects, and vertebrates. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Systematics 49:165–182

Retuerto R, Fernandez-Lema B, Obeso JR (2004) Increased photosynthetic performance in holly trees infested by scale insects. Funct Ecol 18(5):664–669

Rivera-Vega LJ, Acevedo FE, Felton GW (2017) Genomics of Lepidoptera saliva reveals function in herbivory. Curr Opin Insect Sci 19:61–69

Rivero RM, Sánchez E, Ruiz JM, Romero L (2003) Influence of temperature on biomass, iron metabolism and some related bioindicators in tomato and watermelon plants. Jo Plant Physiol 160(9):1065–1071

Sharkey TD, Zhang R (2010) High temperature effects on electron and proton circuits of photosynthesis. J Integr Plant Biol 52(8):712–722

Strapasson P, Pinto-Zevallos DM, Paudel S, Rajotte EG, Felton GW, Zarbin PH (2014) Enhancing plant resistance at the seed stage: low concentrations of methyl jasmonate reduce the performance of the leaf miner Tuta absoluta but do not alter the behavior of its predator Chrysoperla externa. J Chem Ecol 40(10):1090–1098

Strauss SY, Agrawal AA (1999) The ecology and evolution of plant tolerance to herbivory. Trends Ecol Evol 14(5):179–185

Sumesh KV, Sharma-Natu P, Ghildiyal MC (2008) Starch synthase activity and heat shock protein in relation to thermal tolerance of developing wheat grains. Biol Plant 52(4):749–753

Suzuki N, Rivero RM, Shulaev V, Blumwald E, Mittler R (2014) Abiotic and biotic stress combinations. New Phytol 203(1):32–43

Tan CW, Peiffer M, Hoover K, Rosa C, Acevedo FE, Felton GW (2018) Symbiotic polydnavirus of a parasite manipulates caterpillar and plant immunity. Proc Nat Acad Sci 115(20):5199–5204

Tian D, Peiffer M, Shoemaker E, Tooker J, Haubruge E, Francis F, Felton GW (2012) Salivary glucose oxidase from caterpillars mediates the induction of rapid and delayed-induced defenses in the tomato plant. PLoS One 7(4):e36168

Todorov DT, Karanov EN, Smith AR, Hall MA (2003) Chlorophyllase activity and chlorophyll content in wild type and eti 5 mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana subjected to low and high temperatures. Biol Plantarum 46(4):633–636

Triggs AM, Knell RJ (2012) Parental diet has strong transgenerational effects on offspring immunity. Funct Ecol 26(6):1409–1417

Van Der Meijden E, De Boer NJ, Van Der Veen-Van CA (2000) Pattern of storage and regrowth in ragwort. Evol Ecol 14(4–6):439–455

Waldbauer GP (1968) The consumption and utilization of food by insects. In Adv Insect Physiol 5:229–288

War AR, Paulraj MG, Ahmad T, Buhroo AA, Hussain B, Ignacimuthu S, Sharma HC (2012) Mechanisms of plant defense against insect herbivores. Plant Signal Behav 7(10):1306–1320

Waterman JM, Cazzonelli CI, Hartley SE, Johnson SN (2019) Simulated herbivory: the key to disentangling plant defence responses. Trends Ecolog Evol 34(5):447–458

Xiao K, Mao X, Lin Y, Xu H, Zhu Y, Cai Q et al (2017) Trichome, a functional diversity phenotype in plant. Mol Biol 6:183

York, H. A., and Oberhauser, K. S. (2002). Effects of duration and timing of heat stress on monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus)(Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) development. J Kansas Entomol Soc, 290–298

Zangerl AR, Hamilton JG, Miller TJ, Crofts AR, Oxborough K, Berenbaum MR, de Lucia EH (2002) Impact of folivory on photosynthesis is greater than the sum of its holes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99(2):1088–1091

Zavala JA, Casteel CL, DeLucia EH, Berenbaum MR (2008) Anthropogenic increase in carbon dioxide compromises plant defense against invasive insects. Proc Natl Acad USA 105(13):5129–5133

Zobayed SMA, Afreen F, Kozai T (2005) Temperature stress can alter the photosynthetic efficiency and secondary metabolite concentrations in St. John's wort Plant Physiol Biochem 43(10–11):977–984

Zvereva EL, Kozlov MV (2006) Consequences of simultaneous elevation of carbon dioxide and temperature for plant–herbivore interactions: a metaanalysis. Glob Chang Biol 12(1):27–41

Acknowledgements

We thank Michelle Peiffer for her continuous assistance in carrying out the study. This study was supported by grants from the Integrated Pest Management Innovation Lab (IPM IL), United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Agreement No. AID-OAA-L-15-00001 (to E.G.R), US Department of Agriculture Grant AFRI 2017- 67013-26596 (to G.W.F. and K.H.) and National Science Foundation Grant IOS- 1645548 (to G.W.F. and K.H.)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 17 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Paudel, S., Lin, PA., Hoover, K. et al. Asymmetric Responses to Climate Change: Temperature Differentially Alters Herbivore Salivary Elicitor and Host Plant Responses to Herbivory. J Chem Ecol 46, 891–905 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-020-01201-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-020-01201-6