Abstract

Objective

Adjuvantation of an H5N1 split-virion influenza vaccine with AS03A substantially reduces the antigen dose required to produce a putatively protective humoral response and promotes cross-clade neutralizing responses. We determined the effect of adjuvantation on antibody persistence and B- and T-cell-mediated immune responses.

Methods

Two vaccinations with a split-virion A/Vietnam/1194/2004 (H5N1, clade 1) vaccine containing 3.75–30 μg hemagglutinin and formulated with or without adjuvant were administered to groups of 50 volunteers aged 18–60 years.

Results

Adjuvantation of the vaccine led to better persistence of neutralizing and hemagglutination-inhibiting antibodies and higher frequencies of antigen-specific memory B cells. Cross-reactive and polyfunctional H5N1-specific CD4 T cells were detected at baseline and were amplified by vaccination. Expansion of CD4 T cells was enhanced by adjuvantation.

Conclusion

Formulation of the H5N1 vaccine with AS03A enhances antibody persistence and induces stronger T- and B-cell responses. The cross-clade T-cell immunity indicates that the adjuvanted vaccine primes individuals to respond to either infection and/or subsequent vaccination with strains drifted from the primary vaccine strain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Novel influenza viruses arising as a result of antigenic shift can potentially lead to an influenza pandemic in humans due to the lack of immunity in the general population. The 2009 pandemic outbreak was due to the emergence of the influenza A H1N1/2009 virus [1]. The highly pathogenic avian influenza A H5N1 virus, which has been circulating among poultry and birds in several countries during the last decade, remains as a pandemic threat however due to its potential to evolve into a strain with efficient human-to-human transmission [2]. Concern about the H5N1 virus focused attention on the development of pandemic vaccines [3–6]. The experience gained using H5N1 as a model antigen in vaccines can be applied to H1N1/2009 or other pandemic strains. The principal strategy to develop H5N1 vaccines was based on the use of reverse genetics to generate attenuated strains which express H5 surface antigens [7, 8]. The formulation of H5N1 vaccines with oil-in-water adjuvants has been found to substantially enhance vaccine immunogenicity [9–15], thereby minimizing the amount of antigen required and alleviating pressure on the limited global influenza antigen manufacturing capacity.

We conducted a dose–response study with four antigen doses (3.75, 7.5, 15, or 30 μg hemagglutinin antigen—HA) of recombinant H5N1 (A/Vietnam/1194/2004 NIBRG-14, clade 1) split-virion vaccine adjuvanted with AS03A, an oil-in-water emulsion-based Adjuvant System containing α-tocopherol, squalene, and polysorbate-80 [11]. The vaccine was administered as a two-dose schedule to volunteers aged 18–60 years and the study included matched control groups where the same antigen doses were administered without adjuvant [11]. We demonstrated that adjuvantation with AS03A conferred significant antigen sparing so that the hemagglutination–inhibition (HI) antibody response with the lowest antigen dose of 3.75 μg HA met all US and European immunological licensure criteria [11]. Large safety studies [16, 17] with the adjuvanted vaccine indicated a clinically acceptable safety profile and the vaccine has now been licensed in Europe [18].

Another important observation was the ability of AS03A-adjuvanted H5N1 vaccine to induce cross-reactive seroprotective immune responses against heterologous recombinant H5N1 strains. Thus, adjuvantation of the A/Vietnam/1194/2004 H5N1 strain, which belongs to clade 1, induced cross-reactive neutralizing responses against three other H5N1 strains associated with human disease belonging to clade 2 [11, 12]. The same vaccine was also shown to induce protection against heterologous lethal H5N1 challenge in ferrets [19]. An influenza vaccine with cross-immunogenic potential could play a key role in pandemic mitigation by promoting a rapid immune response to infection and/or subsequent vaccination with strains drifted from the primary vaccine strain.

Although an effective vaccination against influenza is routinely measured in terms of the humoral response, it is also important to monitor the induction of antigen-specific T and B cells which are crucial components of the immune response, particularly with respect to long-term memory. In addition to the provision of CD4 T-cell help for B-cell differentiation, both CD4 effector and memory T cells appear to have multifaceted roles in the protective responses to influenza infection [20, 21].

Here, we determine the effect of AS03A adjuvantation on B- and T-cell responses following vaccination with the clade 1 H5N1 A/Vietnam/1194/2004 in the dose–response study. We found that AS03A adjuvantation enhanced antibody persistence, promoted stronger B-cell and CD4 T-cell responses and induced polyfunctional cross-clade T-cell responses to two heterologous clade 2 H5N1 isolates A/Indonesia/5/2005 (subclade 2.1) and A/Anhui/1/2005 (subclade 2.3).

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

This was a single-centre, randomized, and observer-blind phase I clinical trial to assess the safety and immunogenicity of the candidate H5N1 vaccine. The Ethics Committee of the Ghent University Hospital, Ghent, Belgium, approved the protocol and other relevant study documentation and the trial was registered with the ClinicalTrials.gov registry (number NCT00309634). The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki, with written informed consent obtained from all participants. Four hundred healthy male and female volunteers aged 18 to 60 years were enrolled.

Procedures

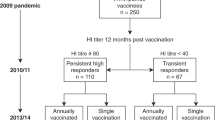

A detailed account of the study procedures has been published along with the results for the co-primary objectives (safety and humoral immune responses at day 42) [11, 12]. The inactivated split A/Vietnam/1194/2004 (NIBRG-14) H5N1 vaccine was manufactured by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals. The vaccine strain, a recombinant H5N1 strain engineered by reverse genetics, was obtained from the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control, UK. Two doses of the vaccine were administered by deltoid muscle injection at 21 days apart to eight groups of 50 volunteers (Fig. 1). Four HA antigen doses (3.75, 7.5, 15, or 30 μg) were given with or without AS03A, an oil-in-water emulsion-based Adjuvant System containing α-tocopherol (11.86 mg) [11], (Morel et al., manuscript submitted).

Blood samples were collected at days 0, 21, 42, and 180 (Fig. 1). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque (Lymphoprep, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) density centrifugation following standard procedures. The cells were washed twice in Hank’s balanced salt solution and cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen until use.

Assessment of Antibody Response

Neutralization and HI assays were performed as described previously [11].

Assessment of Memory B-Cell Response

Memory B cells were induced to differentiate into plasma cells in vitro following cultivation of PBMC with unmethylated DNA (CpG2006 at 3 μg/ml, Eurogentec, Belgium) for 5 days [22]. In vitro-generated antigen-specific plasma cells were enumerated using the memory B-cell detection ELISPOT assay as described by Crotty et al. [22]. Briefly, in vitro-generated plasma cells were incubated in culture plates previously coated with 100 μl of A/Vietnam/1194/2004 NIBRG-14 split antigen at 10 μg/ml or with 100 μl of anti-human IgG at 50 μg/ml (Goat anti-human Affinipure, Jackson Laboratories) in order to enumerate influenza-specific antibody or IgG secreting plasma cells, respectively. The antibody/antigen spots formed were detected by a conventional immuno-enzymatic procedure. The results were expressed as frequencies of influenza-specific memory B cells per million of IgG-producing memory B cells.

Assessment of T-Cell Response

We used an adaptation of the method described by Maecker and coworkers [23, 24] in which the T cells are re-stimulated ex vivo by incubation with antigen in the presence of costimulatory antibodies to CD28 and CD49d [25] and Brefeldin A to inhibit cytokine secretion and allow intracellular accumulation. The cells were then stained using fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies to phenotypic (CD4 or CD8) surface markers, intracellular cytokines, and other markers before enumeration by flow cytometry. To specifically measure the response to H5 antigen, cells were stimulated ex vivo with influenza H5N1 split antigen or H5 peptide pools (with overlaps to ensure all that T-cell epitopes are represented—see below) (Fig. 2). Recombinant H5N1 strains derived from the clade 2 isolates A/Indonesia/5/2005 and A/Anhui/1/2005 were provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Overlapping peptides for T cell stimulation. Sequences of the A/Vietnam and A/Indonesia HA proteins are shown with overlapping peptides indicated in black (conserved) or red (non-conserved). Note that the last conserved A/Indonesia peptide was included in the non-conserved rather than in the conserved pool

Peptides

Peptides (15-mer overlapping by 11 amino acids) spanning the entire H5 HA antigen were synthesized by Eurogentech, Belgium and shown to have >80% purity by HPLC. Lyophilized peptides were reconstituted in phosphate-buffered saline PBS/DMSO (less than 0.1% final concentration). Six different pools of peptides were used for T-cell stimulation. Three of these covered the H5 HA sequences from (1) H5N1 A/Vietnam/1194/2004 (clade 1), (2) H5N1 A/Indonesia/5/2005 (subclade 2.1), and (3) H5N1 A/Anhui/1/2005 (subclade 2.3). Three additional peptide pools, comprising the sequences conserved between A/Vietnam and A/Indonesia or between A/Vietnam, A/Indonesia, and A/Anhui or covering the A/Vietnam sequences that are not conserved in A/Indonesia (Fig. 2), were used.

Antibodies

The antibodies used for cell stimulation were unconjugated and azide-free anti-CD28 and anti-CD49d. The conjugated antibodies used for staining were anti-CD3-PE-Cy5, anti-CD4-PerCP, or -Pacific Blue (PB), anti-CD8-allophycocyanin (APC)-Cy7, anti-IFN-γ-FITC or -PE-Cy7, anti-IL-2-APC or -FITC, anti-TNF-α-PE-Cy7, anti-CD40L-PE, anti-CCR7-FITC, anti-CD45RA-PE, anti-CD27-AlexaFluor 700, and anti-IL-13-PE (all BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA).

Cell Stimulation and Staining

Purified PBMC were thawed, washed twice in culture medium (RPMI 1640, Cambrex, East Rutherford, NJ, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) (PAA Laboratories GMbH, Austria), 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate, 2 mM l-glutamine, MEM nonessential amino acids, 100 mM sodium pyruvate, 50 mM 2-mercapto-ethanol (all from Life Technologies, Belgium), examined for viability and counted (Trucount, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA USA), washed again, and resuspended to 2 × 107 cells/ml in culture medium. The PBMC (106 cells per well) were incubated in 96-well microtiter plates with costimulatory anti-human CD28 and CD49d antibodies (1/250 dilution each) and stimulated for 20 h at 37°C with either H5N1 split antigen from the A/Vietnam/1194/2004 NIBRG-14 vaccine strain (final concentration 1 μg/ml HA) or one of the peptide pools (final concentration 1.25 μg/ml of each peptide). Brefeldin A (BD Pharmingen, final concentration 1 μg/ml) was added for the last 18 h of culture. Positive (Staphylococcus enterotoxin B, 1 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and negative controls (unstimulated; no antigen) were included in each assay. Following incubation, the cells were washed (PBS containing 1% FCS) and stained with anti-CD4-PerCP and anti-CD8- APC- Cy7. The cells were then washed again, fixed, and permeabilized with the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Pharmingen) according to instructions and stained with anti-IFN-γ-FITC, anti-IL-2-APC, anti-TNF-α-PE Cy7, and anti-CD40L-PE. Following washing (Perm/Wash buffer, BD Pharmingen), the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. To characterize IFN-γ and IL-13 (Th1/Th2)-expressing T cells after in vitro stimulation, we followed the same protocol as described above but used anti-IFN-γ-PE-Cy7, anti-IL-2-FITC, and anti-IL-13-PE for intracellular staining. The procedure to characterize the memory phenotype of antigen-specific T cells differed from the one described above in that anti-CCR-7-FITC was incubated at the onset of in vitro incubation, followed by extra-cellular staining with anti-CD3-PE-Cy5.5, anti-CD4-PB, anti-CD8-APC-Cy7, and anti-CD27-Alexa Fluor 700 in addition to anti-IL-2 APC and anti-IFN-γ-PE Cy7.

Flow Cytometry

Cells were acquired on a FACSCanto flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) using six-color panels. Data were analyzed using FACSDiva software. The results were expressed as frequencies of CD4 or CD8 T cells responding to the antigen and expressing two or more immune markers among CD40L, IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α per million total CD4 or CD8 T cells. Background (unstimulated control) was subtracted from all values. The remaining positive events were regarded as significant. Samples were only included for analysis if viability was 80% or more. The analyses identifying the Th profiles and the memory phenotypes of the specific T cells are described in the “Results” section.

Data Analysis

The HI antibody response was presented in terms of geometric mean titers (GMTs) at all time points for all eight vaccine groups as well as in terms of seroconversion rates (SCRs), i.e., the percentage of subjects with post-vaccination titers ≥1:40 (deemed to be the seroprotective threshold for seasonal influenza vaccines). We analyzed the cellular immune responses (for 3.75 and 7.5 μg HA formulations or 3.75 μg HA formulations only) for the per-protocol population as the median (and interquartile ranges Q1 and Q3) specific T or memory B cell numbers per million total T or memory B cells prior to vaccination (day 0) at 21 days following the first vaccine dose (day 21; note that this time point was used only to measure T-cell responses after stimulation with A/Vietnam/1194/2004 H5N1 split antigen), at 21 days following the second vaccine dose (day 42), and at 180 days following the first vaccine dose (day 180). The B-cell response endpoint was the frequency of memory B cells responding to H5N1 split antigen for each vaccine group. The T-cell response endpoints were the frequencies of CD4 or CD8 T cells expressing two or more immune markers among CD40L, IL-2, TNF-α, and IFN-γ upon short term in vitro stimulation with A/Vietnam/1194/2004 H5N1 split antigen or H5 peptide pools. CMI results were further analyzed in terms of CD4 T cells expressing (1) CD40L and at least one other marker (IFN-γ, IL-2, or TNF-α), (2) IL-2 and at least one other marker (CD40L, TNF-α, or IFN-γ), (3) TNF-α and at least one other marker (CD40L, IL-2, or IFN-γ), or (4) IFN-γ and at least one other marker (IL-2, TNF-α, or CD40L) for each vaccine group. To test the adjuvantation and dose effects, we compared the B- or T-cell frequencies in the adjuvanted and non-adjuvanted groups using the Kruskal–Wallis test. Comparisons were done for day 42 values, for day 42 minus day 0 values (to account for any differences in pre-vaccination day 0 values), and for day 180 values.

Results

Antibody and B-Cell Responses

To evaluate the immunogenicity and safety of the AS03A-adjuvanted A/Vietnam/1194/2004 H5N1 vaccine, we conducted a single-center, randomized, observer-blind phase I clinical trial [11]. The subjects in this trial received two immunizations at a 21-day interval with either adjuvanted or non-adjuvanted vaccine (Fig. 1). Blood samples were collected at days 0, 21, 42, and 180 and used for the analysis of antibody, B-cell, and CD4 T-cell responses.

An analysis of neutralizing GMTs specific for A/Vietnam/1194/2004 antigen provided a clear evidence for the enhancing effect of adjuvant on both the magnitude [11] and the persistence of the antibody response. Indeed the enhancing effect of the adjuvant on the antibody response against Vietnam/1194/2004 H5N1 was still evident at 6 months after the first vaccination (day 180) (Fig. 3a). An evaluation of the SCRs of neutralizing and HI antibodies supported this conclusion. Neutralizing antibody SCRs at day 180 were 72% and 66% in the 3.75 and 7.5 μg HA-adjuvanted groups versus 8% and 21% in the corresponding non-adjuvanted groups, respectively (data not shown). HI SCRs at day 180 were 54% and 64% compared with 4% and 14% in the corresponding non-adjuvanted groups for the 3.75 and 7.5 μg HA formulations, respectively (Fig. 3b).

a Neutralizing antibody GMTs against the homologous A/Vietnam/1194/2004 NIBRG-14 vaccine strain after the first and second vaccine dose with 95% confidence intervals. Data shown for all groups at the different time points. b SCRs of HI antibodies to the homologous A/Vietnam/1194/2004 NIBRG-14 vaccine strain after the first and second vaccine dose with 95% confidence intervals

To determine whether the impact of the adjuvant on the magnitude and persistence of the antibody responses would be paralleled by enhanced B-cell responses, we measured the frequencies of memory B cells specific for A/Vietnam H5N1 split antigen (further referred to as ‘split antigen’) at the different time points in the groups vaccinated with the 3.75 μg HA dose with or without adjuvant. H5N1-specific memory B cells were detectable prior to vaccination (Fig. 4) at comparable frequencies in the two groups. At day 21 following the administration of the first vaccine dose, increases in memory B-cell frequencies were observed in both groups but the relative increase was higher in the adjuvanted 3.75 μg HA group than in the non-adjuvanted 3.75 μg HA group (Fig. 4). The administration of the second vaccine dose at day 21 further increased the response in the adjuvanted group, as measured on day 42, but had no impact in the non-adjuvanted group. Thus, the frequency of H5N1-specific memory B cells was significantly higher in the adjuvanted group versus the non-adjuvanted group when assessed either as day 42 values (p < 0.001) or as day 42 minus day 0 values (p < 0.001). The enhancing effect of the adjuvant on the memory B-cell response observed on day 42 was still evident at day 180 (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4). Similar results were found for the higher 7.5 μg HA vaccine dose, although in this case the data were only available for days 0 and 42 (Fig. 4).

Frequencies of memory B cells specific to the split-virion A/Vietnam/1194/2004 NIBRG-14 strain obtained before vaccination (Pre), at 21 days after the first dose (D21), and at 21 or 159 days after the second dose (D42 and D180). Data shown are for the study groups administered with 3.75 μg HA (all time points) or 7.5 μg HA (Pre and D21) of recombinant H5N1 (A/Vietnam/1194/2004 NIBRG-14) split-virion vaccine adjuvanted with AS03A or unadjuvanted (AS03 vs Plain)

CD4 T-Cell Response to A/Vietnam/1194/2004 H5N1 Split Antigen

Following the observation that the adjuvant had a positive effect on long-lived HI antibody responses and memory B-cell frequencies, we investigated whether these improved responses would be associated with similar changes in the H5N1-specific CD4 T-cell responses. To this end, A/Vietnam/1194/2004 H5N1-specific CD4 T-cell responses were measured in the two lowest dose groups (3.75 and 7.5 μg HA) with or without adjuvant by intracellular cytokine staining (Fig. 5a) [23, 24] following overnight stimulation of PBMC with A/Vietnam/1194/2004 H5N1 split antigen and using the expression of CD40L, IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α as read-outs. H5N1-specific CD4 T-cell responses, defined as CD4 T cells producing at least two of these immune markers after the stimulation, were evident in all the groups prior to vaccination (Fig. 5a). Vaccination induced increased frequencies of H5N1-specific CD4 T cells in all groups (compare day 21 with day 0; Fig. 5a). However, while a modest increase was observed in groups receiving non-adjuvanted vaccine (p < 0.0001 when comparing day 21 or 42 response to day 0 response), much stronger responses were observed in the groups that received adjuvanted vaccine. The second vaccination did not result in an increase of the CD4 T-cell frequency when measured at day 42, i.e., at 21 days after the second vaccination. The adjuvant had a clear enhancing effect on the T-cell response as demonstrated by the significantly higher post-vaccination frequencies of H5N1-specific CD4 T cells (when comparing adjuvanted and non-adjuvanted formulations, p < 0.0001 for day 21 and p < 0.0001 for day 42 values) (Fig. 5a). H5N1-specific CD4 T cells were still detectable at day 180 (Fig. 5a), indicating the persistence of the T-cell response. The frequencies remained significantly higher (p = 0.0001) in the adjuvanted formulation groups as compared to the non-adjuvanted ones at day 180. Both within the adjuvanted and non-adjuvanted groups, no statistically significant antigen dose effects on the H5N1-specific CD4 T-cell response were observed (3.75 versus 7.5 μg HA) (Fig. 5a).

a Frequencies of CD4 T cells specific to the split-virion A/Vietnam/1194/2004 NIBRG-14 strain obtained before vaccination (Pre), 21 days after the first dose (D21), and 21 or 159 days after the second dose (D42 and D180) in study groups administered with 3.75 or 7.5 μg HA of recombinant H5N1 (A/Vietnam/1194/2004 NIBRG-14, clade 1) split-virion vaccine adjuvanted with AS03A or unadjuvanted (AS03 vs plain). b Functional characterization of the split-virion A/Vietnam/1194/2004-specific CD4 T cells obtained at 21 days after the second vaccination in study groups administered with 3.75 or 7.5 μg HA of recombinant H5N1 (A/Vietnam/1194/2004 NIBRG-14, clade 1) split-virion vaccine adjuvanted with AS03A or not (AS03 vs plain). The frequencies of specific CD4 T cells are represented as expressing (after in vitro stimulation) two or more immune markers among CD-40 L, IL-2, TNF-α, or IFN-γ (‘all double’) or expressing CD40L, IL-2, TNF-α, or IFN-γ and at least one of the other immune markers evaluated within CD-40 L, IL-2, TNF-α, or IFN-γ (indicated as +CD40L+, +IL-2+, +TNF-α+, +IFN-γ+)

In six out of 200 subjects, antigen-specific CD8 T cells producing IFN-γ and TNF-α were detected in pre-vaccination samples following stimulation with split antigen. However, vaccination did not have any impact on the frequencies of these CD8 T cells as measured at 21 days after vaccination (data not shown).

The H5N1-Specific CD4 T-Cell Pool is Composed of Polyfunctional Effector and Memory Cells

The polyfunctionality of H5N1-specific CD4 T-cell responses was evaluated on the basis of the expression patterns of CD40L, IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α in antigen-stimulated CD4 T cells. The predominant vaccine-induced response following ex vivo stimulation with A/Vietnam/1194/2004 split antigen consisted of CD40L- and IL-2-producing CD4 T cells (Fig. 5b). A similar pattern was observed in H5N1-specific CD4 T cells at baseline (data not shown). When expressed as antigen-specific CD4 T cells expressing at least two immune markers (‘all doubles’), fewer CD4 T cells expressed IFN-γ and/or TNF-α as compared to CD40L/IL-2-double-positive CD4 T cells (Fig. 5b). This pattern was observed for both the 3.75 and 7.5 μg HA formulations (Fig. 5b). In each subpopulation, higher frequencies were observed in the adjuvanted groups (Fig. 5b). Indeed the frequencies of all polyfunctional H5N1-specific CD4 T cells (expressing all marker combinations) at day 42 were significantly higher in the adjuvanted 3.75 and 7.5 μg HA formulation groups than in the corresponding non-adjuvanted formulation groups (all p < 0.0001 for both day 42 values and day 42 minus day 0 values) (data not shown).

To examine the Th1/Th2 balance of the response, IL-13 production in antigen-specific CD4 T cells was analyzed by intracellular cytokine staining and compared with IFN-γ expression in adjuvanted and non-adjuvanted groups (Fig. 6). PMA/ionomycin-stimulated CD4 T cells were used as a positive control for IL-13 staining (data not shown). Very few IL-13-producing CD4 T cells were detected at day 42, whereas IFN-γ/IL-2 double-positive CD4 T cells were readily observed. In addition, no increase in the frequencies of IL-13-secreting CD4 T cells was observed when comparing day 42 with day 0 (Fig. 6).

Frequencies of CD4 T cells specific to the split-virion A/Vietnam/1194/2004 NIBRG-14 strain expressing IFN-γ (IFNγ +) or IL-13 (IL-13 +) obtained before (Pre) and 21 days after the second dose (D42) in study groups administered with 3.75 or 7.5 μg HA of recombinant H5N1 (A/Vietnam/1194/2004 NIBRG-14, clade 1) split-virion vaccine adjuvanted with AS03A or not (AS03 vs plain)

Having established that H5N1 vaccination leads to an increase in the frequencies of polyfunctional H5N1-specific CD4 T cells, we next evaluated the phenotypic characteristics of these cells and their differentiation into memory cells. To this end, CD45RA, CCR7, and CD27 were used as phenotypic markers to distinguish effector, effector–memory, and central memory T cells [20, 26–28]. H5N1-specific CD4 T cells were identified as IFN-γ- and/or IL-2-producing CD4 T cells after stimulation with either H5N1 split antigen or a pool of overlapping peptides spanning the entire A/Vietnam/1194/2004 H5 HA sequence (Fig. 2). All H5N1-specific CD4 T cells, at day 42, were CD45RAneg (data not shown). Cytokine expression patterns clearly revealed three different populations of antigen-specific CD4 T cells: IL-2+/IFN-γ−, IL-2−/IFN-γ+, and IL-2+/IFN-γ+ (Fig. 7a). A phenotypic analysis of these three populations, using CCR7 and CD27 as markers, revealed that the IL-2−/IFN-γ+ cells were mainly CCR7− CD27− effector/effector–memory cells, whereas the population of IL-2+ T cells, with or without IFN-γ, respectively (IL-2+/IFN-γ+ and IL-2+/IFN-γ−), consisted of CCR7+ CD27+ central memory cells and CCR7− CD27+ effector–memory cells (Fig. 7a). A quantitative analysis indicated that the response was dominated by CCR7− CD27+ effector–memory CD4 T cells, with smaller populations of CCR7+ CD27+ central memory cells and CCR7− CD27− effector/effector–memory cells (Fig. 7b). Although the amplitude of the H5N1-specific response was significantly higher in the groups vaccinated with adjuvanted vaccine, the ratios between the three major populations were stable over time (day 42 compared to day 180), were similar to the pre-vaccination pattern, and did not differ between the adjuvanted and non-adjuvanted groups (Fig. 7b).

a Expression of CCR7 and CD27 on H5N1-specific CD4 T cells obtained after stimulation of PBMC with a pool of peptides spanning the A/Vietnam/1194/2004 H5 sequence. Antigen-specific CD4 T cells were identified by intracellular cytokine staining (left panel) and analyzed for the expression of the CCR7 and CD27 memory markers (right panel). b Distribution of the different CCR7/CD27 expression patterns at different time points (D0, D42, and D180) and after vaccination with 3.75 μg HA AS03A-adjuvanted (‘adj’) or non-unadjuvanted vaccine

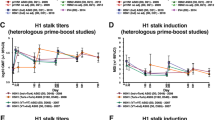

H5N1 A/Vietnam/1194/2004 vaccine-induced CD4 T-cell responses are clade 2 cross-reactive

As we have shown previously, vaccination with the clade 1 H5N1 A/Vietnam/1194/2004 vaccine induced clade 2 cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies [11, 12]. To determine whether this cross-reactive humoral response was associated with similarly cross-reactive CD4 T-cell responses, PBMC were stimulated with sets of peptides spanning the HA sequences from A/Vietnam/1194/2004 (clade 1) and the clade 2 strains H5N1 A/Indonesia/5/2005 (subclade 2.1) and A/Anhui/1/2005 (subclade 2.3) (Figs. 2 and 8a). With respect to the A/Vietnam-specific responses, it was observed that the absolute frequencies of CD4 T cells responding to the peptide pool (Fig. 8b) were lower than those observed after H5N1 split antigen stimulation (Fig. 5a). A possible explanation for this difference may be that the peptide pools do not contain split virus components such as the neuraminidase N1 protein. Nevertheless, HA-specific CD4 T-cell responses were observed for all six peptide pools used, at day 42 as well as at day 0, albeit to a lower extent (Fig. 8b). These data demonstrate that the clade 1 H5N1 A/Vietnam/1194/2004 vaccine induced a clade 2 cross-reactive CD4 T-cell response (A/Indonesia/5/2005 and A/Anhui/1/2005) and also confirm that a pool of cross-reactive CD4 T cells existed before vaccination. In all cases, responses were dominated by CD40L+ IL-2-producing CD4 T cells, with fewer cells expressing IFN-γ and TNF-α (data not shown). Thus, the CD40L and cytokine expression patterns of the HA-specific CD4 T cells for all three H5N1 strains were similar to those observed after the stimulation with the A/Vietnam/1194/2004 split antigen (Fig. 5b). In addition, the responses were measured against the conserved regions of the HA antigen using two peptide pools covering the sequences that are identical between A/Vietnam and A/Indonesia or between all three H5N1 strains. Finally, the responses were measured against the region that is unique to the A/Vietnam strain (Figs. 2 and 8a). As might be expected, a response was evident following ex vivo stimulation with the peptide pool covering the conserved region (Fig. 8b). Also, a CD4 T-cell response was observed to the peptide pool spanning the region that is unique to A/Vietnam/1194/2004 (Fig. 8b). In all cases, cross-reactive CD4 T-cell responses were clearly enhanced by the presence of the adjuvant.

a Schematic representation of the peptide pool design covering conserved and unconserved amino acid sequences between H5N1 A/Vietnam/1194/2004 and A/Indonesia/5/2005 strains. b Frequencies of CD4 T cells specific to the HA proteins of A/Vietnam, A/Indonesia, or A/Anhui or specific to the conserved and unconserved sequences among these three strains (Vietnam–Indonesia conserved, Vietnam–Indonesia non-conserved, Vietnam–Indonesia–Anhui conserved). CD4 T-cell responses were obtained before (Pre) and 21 days after the second dose (D42) in study groups administered with 3.75 or 7.5 μg HA of recombinant H5N1 (A/Vietnam/1194/2004 NIBRG-14, clade 1) split-virion vaccine adjuvanted with AS03A or unadjuvanted (AS03 vs unadjuvanted)

Discussion

We have previously shown that the formulation of a clade 1 A/Vietnam/1194/2004 H5N1 split-virion vaccine with an α-tocopherol containing oil-in-water emulsion-based Adjuvant System (AS03A) induced broad clade 2 cross-reactive humoral immunity and reduced the amount of antigen required to produce a humoral response that meets the European Union Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use and US Food and Drug Administration licensure criteria [11, 12]. Two doses of adjuvanted H5N1 split-virion vaccine containing 3.75 μg HA induced high levels of neutralizing and HI antibodies against the clade 1 vaccine strain, as well as a significant cross-reactive neutralizing antibody response against the clade 2 H5N1 isolates A/Indonesia/5/2005 (subclade 2.1), A/turkey/Turkey/1/2005 (subclade 2.2), and A/Anhui/1/2005 (subclade 2.3) [11, 12]. Here, we have investigated the CD4 T-cell and memory B-cell responses underlying these cross-reactive antibody responses. CD4 T-cell responses were detected by intracellular cytokine staining after stimulation with either split virus or overlapping peptides. The present study makes four points: First, we show that all responses, i.e., antibodies, B cell memory, and CD4 T cells, are increased when the vaccine is formulated with AS03A adjuvant. Second, persistent neutralizing antibody responses are mirrored by long-lived memory B-cell responses. Third, vaccination induces polyfunctional and highly cross-reactive CD4 T-cell responses and results in long-lived central and effector CD4 T-cell memory. Fourth, H5N1-specific CD4 T and memory B cells are already detected before vaccination.

We observed stronger memory B-cell responses for the H5N1 antigen when the vaccine was formulated with adjuvant. Memory B-cell frequencies were increased after the first vaccination and rose further after the second vaccination. Since antibody-secreting plasma cells and memory B cells may represent independently regulated cell populations [29], long-lived memory B cells may not play a direct role in the maintenance of antibody levels, but they could differentiate into plasma cells after booster vaccination or natural infection. Therefore, higher levels of memory B cells would predict a better ‘boostability’ of the response. We further observed increased H5N1-specific CD4 T-cell responses with the adjuvanted vaccine. The frequencies of antigen-specific, polyfunctional CD4 T cells increased strongly at day 21 post-vaccination with the adjuvanted vaccine. There appeared to be no increase in the response after the second vaccination, i.e., at day 42. A possible explanation for this perceived lack of further expansion is that the peak of the CD4 T-cell response occurred earlier after the second vaccination [30] and that the day 42 time point measures the response in the contraction phase. Alternatively, it is possible that specific CD4 T cells may have migrated towards the injection site, thereby affecting CD4 T-cell frequencies in peripheral blood. The fact that the response levels at days 21 and 42 were nearly identical may suggest that the antigen-specific CD4 T cells underwent an expansion phase prior to the day 42 sampling time point. Further investigation of the kinetics of the response should shed further light on this question.

Phenotypically, the responding CD4 T-cell population consisted of both effector–memory-like cells (CD45RA−, CCR7−, CD27+/−) and central memory cells (CD45RA−, CCR7+, CD27+) with a tendency for CCR7− CD27+ effector–memory cells to dominate the response at day 180. Overall, the adjuvanted vaccine induced a significantly larger memory pool as compared to the non-adjuvanted vaccine. The functional profiles of the responding CD4 T cells were similar for both adjuvanted and non-adjuvanted vaccines, with responses being dominated by CD40L+- and IL-2-producing cells. Fewer IFN-γ- and TNF-α-producing cells were evident. This bias towards IL-2-producing CD4 T cells was noted previously in healthy adults that received the hepatitis B virus, tetanus, or diphtheria vaccines [30, 31] and it has been suggested that this phenotype is typical for protein subunit vaccines in general [31].

Overall, the H5N1-specific CD4 T-cell responses had a Th1 bias and very few IL-13-producing cells were detected at any time point. Confirming recently published results [32], cross-reactive CD8 T-cell responses were measured at baseline, indicating the capacity of our assay to detect CD8 T-cell responses. However, no increased CD8 T-cell responses were observed after vaccination, which is in contrast to the responses usually induced by a viral infection [33]. Indeed FluMist® (MedImmune LLC, Gaithersburg, MD), which is a live-attenuated influenza vaccine, induces CD8 T-cell responses [20]. Besides the antigen content, the most likely explanation for this is that protein antigens are efficiently presented through the MHC class II pathway but not via the MHC class I pathway. The induction of CD8 T-cell responses to protein antigen depends on the cross-presentation pathway which, in mice, critically depends on type-I IFN [34] and specialized CD8α+ DCs, but which is not yet fully understood in humans.

Immune responses to inactivated influenza virus adjuvanted with a different oil-in-water emulsion, MF59, have recently been described [35, 36]. Although a direct comparison between the adjuvants is complicated by the fact that different methodologies may have been used to measure immune responses, our data indicate that AS03A-adjuvanted influenza vaccines induce strong HI responses and CD4 T-cell frequencies relative to those induced with the MF59-adjuvanted product.

It is interesting to note that H5-specific CD4 T cells and H5N1-specific memory B cells were detectable prior to vaccination. The identification of CD4 T-cell responses after peptide stimulation in day 0 samples clearly indicates that an H5-specific T-cell response exists before vaccination. However, since the split antigen used for the stimulation of B cells and CD4 T cells also contains the neuraminidase (NA) protein, it cannot be excluded that part of the pre-existing response was in fact specific for NA. Indeed there was a discrepancy between readily detected pre-existing H5N1-specific memory B cells and weaker pre-existing A/Vietnam-specific HI responses (detectable in only seven of 400 subjects (11)).

No correlations were observed between the frequencies of pre-existing H5N1-specific CD4 T cells and post-vaccination HI titers at days 42 or 180. Moreover, there was no correlation between the frequencies of pre-existing H5N1-specific CD4 T cells and post-vaccination CD4 T-cell responses, suggesting that at least part of the response is not dependent on pre-existing CD4 memory T cells.

Pre-existing memory CD4 T cells responded to peptide pools covering the HA sequences from the clade 1 A/Vietnam/1194/2004 vaccine virus as well as the clade 2 A/Indonesia virus. This suggests that the H5-cross-reactive CD4 T cells were induced by a previous infection with seasonal influenza. Thus, these results confirm recently published data showing that memory CD4 T cells, and also CD8 T cells, established by seasonal influenza A cross-react with H5N1 strains [32]. The combined data raise the question on whether this memory T-cell pool expands after vaccination, instead of or in addition to the naïve T-cell repertoire. A further question is how this potential balance between the recruitment of naïve and memory responses is affected by the adjuvant. A related question is whether the adjuvant simply amplifies the response induced by the non-adjuvanted vaccine (i.e., more of the same) or whether it induces qualitative changes in the repertoire of the responding T cells (i.e., more but not the same). Recent data indicate that vaccine adjuvants change the clonal composition of antigen-specific CD4 T-cell populations responding to vaccines, favoring the selection of higher-affinity T cells [37]. Thus, it seems likely that the adjuvant changes the T-cell response both quantitatively and qualitatively.

Adjuvantation of the split antigen vaccine with AS03A resulted in a strong increase in the numbers of antigen-specific B cells and CD4 T cells. AS03A does not contain a ‘classical’ TLR ligand and further studies into its mode of action are ongoing. Based on the results presented here and our recent data on the mode of action of the AS03A Adjuvant System (Morel et al., manuscript submitted), we propose the following model: AS03A induces a recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes at the injection site and induces the maturation of the recruited monocytes. Indeed AS03A activates monocytes and macrophages but not dendritic cells (Morel et al., manuscript submitted). Our current data show that the presence of α-tocopherol in AS03 was required to achieve an optimal antibody response in mice immunized with HBsAg (Morel et al., manuscript submitted). Furthermore, the presence of α-tocopherol in the AS03A Adjuvant System modulated the levels and kinetics of other cytokines and chemokines, including CCL2, CCL3, IL-6, CSF3, and CXCL1, increased the antigen loading in monocytes, and increased the recruitment of granulocytes in the draining lymph nodes (Morel et al., manuscript submitted). Thus, the ability of α-tocopherol to qualitatively and quantitatively modulate the innate immune response is correlated with a positive impact on the adaptive immune responses in pre-clinical models. Interestingly, IL-6 has been involved in the induction of follicular T helper cells [38] which are essential to provide B-cell help and to promote germinal center reactions. This, in turn, could lead to increased antibody responses.

Conclusions

In summary, we show that the AS03A-adjuvanted H5N1 split-virion vaccine is capable of inducing superior antibody, memory B-cell and CD4 T-cell responses when compared to non-adjuvanted vaccine and that the CD4 T-cell responses were notably cross-reactive with clade 2 viruses. The induction of cross-clade immune responses clearly indicates that H5N1 vaccines formulated with AS03A could prime against infection or revaccination with drifted strains. This property of the adjuvanted vaccine is appealing in the context of the development of a vaccine against the 2009 H1N1 A/California pandemic strain and the potential of this vaccine to protect against drifted strains.

References

Girard MP, Tam JS, Assossou OM, Kieny MP. The 2009 A (H1N1) influenza virus pandemic: a review. Vaccine. 2010;28:4895–902.

World Health Organization. Avian influenza. World Health Organization. 2009. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/avian_influenza/en/index.html. Accessed 27 Aug 2010.

European Agency for Proprietary Medicinal Products. Guideline on influenza vaccine prepared from viruses with the potential to cause a pandemic and intended for use outside of the core dossier context (EMEA/CHMP/VWP/263499/2006). European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products; 2007.

Leroux-Roels I, Leroux-Roels G. Current status and progress of prepandemic and pandemic influenza vaccine development. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2009;8:401–23.

Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: clinical data needed to support the licensure of pandemic influenza vaccines. 2007.

European Agency for Proprietary Medicinal Products. Guideline on dossier structure and content for pandemic influenza vaccine marketing authorisation application (CPMP/VEG/4717/03). European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products; 2004.

Nicolson C, Major D, Wood JM, Robertson JS. Generation of influenza vaccine viruses on Vero cells by reverse genetics: an H5N1 candidate vaccine strain produced under a quality system. Vaccine. 2005;23:2943–52.

Webby RJ, Perez DR, Coleman JS, Guan Y, Knight JH, Govorkova EA, et al. Responsiveness to a pandemic alert: use of reverse genetics for rapid development of influenza vaccines. Lancet. 2004;363:1099–103.

Banzhoff A, Gasparini R, Laghi-Pasini F, Staniscia T, Durando P, Montomoli E, et al. MF59-adjuvanted H5N1 vaccine induces immunologic memory and heterotypic antibody responses in non-elderly and elderly adults. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4384.

Bernstein DI, Edwards KM, Dekker CL, Belshe R, Talbot HK, Graham IL, et al. Effects of adjuvants on the safety and immunogenicity of an avian influenza H5N1 vaccine in adults. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:667–75.

Leroux-Roels I, Borkowski A, Vanwolleghem T, Drame M, Clement F, Hons E, et al. Antigen sparing and cross-reactive immunity with an adjuvanted rH5N1 prototype pandemic influenza vaccine: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370:580–9.

Leroux-Roels I, Bernhard R, Gerard P, Drame M, Hanon E, Leroux-Roels G. Broad Clade 2 cross-reactive immunity induced by an adjuvanted clade 1 rH5N1 pandemic influenza vaccine. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1665.

Levie K, Leroux-Roels I, Hoppenbrouwers K, Kervyn AD, Vandermeulen C, Forgus S, et al. An adjuvanted, low-dose, pandemic influenza A (H5N1) vaccine candidate is safe, immunogenic, and induces cross-reactive immune responses in healthy adults. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:642–9.

Schwarz TF, Horacek T, Knuf M, Damman HG, Roman F, Drame M, et al. Single dose vaccination with AS03-adjuvanted H5N1 vaccines in a randomized trial induces strong and broad immune responsiveness to booster vaccination in adults. Vaccine. 2009;27:6284–90.

Stephenson I, Nicholson KG, Hoschler K, Zambon MC, Hancock K, DeVos J, et al. Antigenically distinct MF59-adjuvanted vaccine to boost immunity to H5N1. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1631–3.

Chu DW, Hwang SJ, Lim FS, Oh HM, Thongcharoen P, Yang PC, et al. Immunogenicity and tolerability of an AS03(A)-adjuvanted prepandemic influenza vaccine: a phase III study in a large population of Asian adults. Vaccine. 2009;27:7428–35.

Rümke HC, Bayas JM, de Juanes JR, Caso C, Richardus JH, Campins M, et al. Safety and reactogenicity profile of an adjuvanted H5N1 pandemic candidate vaccine in adults within a phase III safety trial. Vaccine. 2008;26:2378–88.

EMEA. European public assessment report for Prepandrix, 2010.

Baras B, Stittelaar KJ, Simon JH, Thoolen RJMM, Mossman SP, Pistoor FHM, et al. Cross-protection against lethal H5N1 challenge in ferrets with an adjuvanted pandemic influenza vaccine. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1401.

Doherty PC, Turner SJ, Webby RG, Thomas PG. Influenza and the challenge for immunology. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:449–55.

Swain SL, Agrewala JN, Brown DM, Jelley-Gibbs DM, Golech S, Huston G, et al. CD4+ T-cell memory: generation and multi-faceted roles for CD4+ T cells in protective immunity to influenza. Immunol Rev. 2006;211:8–22.

Crotty S, Aubert RD, Glidewell J, Ahmed R. Tracking human antigen-specific memory B cells: a sensitive and generalized ELISPOT system. J Immunol Methods. 2004;286:111–22.

Maecker HT. Multiparameter flow cytometry monitoring of T cell responses. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;485:375–91.

Nomura L, Maino VC, Maecker HT. Standardization and optimization of multiparameter intracellular cytokine staining. Cytom A. 2008;73:984–91.

Waldrop SL, Davis KA, Maino VC, Picker LJ. Normal human CD4+ memory T cells display broad heterogeneity in their activation threshold for cytokine synthesis. J Immunol. 1998;161:5284–95.

Sallusto F, Geginat J, Lanzavecchia A. Central memory and effector memory T cell subsets: function, generation, and maintenance. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:745–63.

de Bree GJ, Daniels H, Schilfgaarde M, Jansen HM, Out TA, van Lier RA, et al. Characterization of CD4+ memory T cell responses directed against common respiratory pathogens in peripheral blood and lung. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1718–25.

Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Understanding the generation and function of memory T cell subsets. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:326–32.

Amanna IJ, Carlson NE, Slifka MK. Duration of humoral immunity to common viral and vaccine antigens. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1903–15.

Cellerai C, Harari A, Vallelian F, Boyman O, Pantaleo G. Functional and phenotypic characterization of tetanus toxoid-specific human CD4+ T cells following re-immunization. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1129–38.

Divekar AA, Zaiss DM, Lee FE, Liu D, Topham DJ, Sijts AJ, et al. Protein vaccines induce uncommitted IL-2-secreting human and mouse CD4 T cells, whereas infections induce more IFN-gamma-secreting cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:1465–73.

Lee LYH, Ha DLA, Simmons C, de Jong MD, Chau NV, Schumacher R, et al. Memory T cells established by seasonal human influenza A infection cross-react with avian influenza A (H5N1) in healthy individuals. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3478–90.

Wherry EJ, Ahmed R. Memory CD8 T-cell differentiation during viral infection. J Virol. 2004;78:5535–45.

Le Bon A, Tough DF. Type I interferon as a stimulus for cross-priming. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2008;19:33–40.

Galli G, Medini D, Borgogni E, Zedda L, Bardelli M, Malzone C, et al. Adjuvanted H5N1 vaccine induces early CD4+ T cell response that predicts long-term persistence of protective antibody levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3877–82.

Galli G, Hancock K, Hoschler K, DeVos J, Praus M, Bardelli M, et al. Fast rise of broadly cross-reactive antibodies after boosting long-lived human memory B cells primed by an MF59 adjuvanted prepandemic vaccine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7962–7.

Malherbe L, Mark L, Fazilleau N, Heyzer-Williams LJ, Heyzer-Williams MG. Vaccine adjuvants alter TCR-based selection thresholds. Immunity. 2008;28:698–709.

Nurieva RI, Chung Y, Hwang D, Yang XO, Kang HS, Ma L, et al. Generation of T follicular helper cells is mediated by interleukin-21 but independent of T helper 1, 2, or 17 cell lineages. Immunity. 2008;29:138–49.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) Biologicals. GSK Biologicals provided the funding source and was involved in all stages of the study conduct and analysis. GSK Biologicals also took charge of all costs associated with the development and the publishing of the present manuscript. All authors had full access to the data and had final responsibility in submitting such for publication. We thank the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (Potters Bar, UK) for providing the vaccine virus strain and reference standards and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, Atlanta, USA) for supplying the A/Indonesia/5/2005 strain. The authors are indebted to the study volunteers, participating clinicians, nurses, and laboratory technicians at the study site and the sponsor’s project staff for their support and contributions throughout the study. We wish to thank Michel Janssens, Olivier Jauniaux, Sarah Charpentier, Valerie Mohy, Michael Mestre, Dinis Fernandes-Ferreira, Pierre Libert, Samira Hadiy, Murielle Carton, Luc Franssen, and Caroline Herve for their enthusiastic participation in this work; Jeanne-Marie Devaster, François Roman, and Paul Gillard for their involvement in the study; and Michel Bourgois for the help with statistical analyses. Finally, we thank Miriam Hynes (independent, UK) who provided medical writing services on behalf of GSK Biologicals and Ulrike Krause, Ellen Oe, Isabelle Gautherot, and Sophie Tambour for editorial assistance. FluMist® is a registered trademark of MedImmune, LLC.

Conflicts of interest

Geert Leroux-Roels has been a principal investigator of vaccine trials for several manufacturers, including GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, for which his institution obtained research grants. Geert Leroux-Roels has received honoraria for participation in scientific advisory boards. Isabel Leroux-Roels and Geert Leroux-Roels received speaker fees and travel grants from several manufacturers, including GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals. Frédéric Clement has no declared conflict of interest. Dr. Robbert van der Most, Dr. Philippe Moris, Dr. Mamadou Dramé, Dr. Emmanuel Hanon, and Dr. Marcelle Van Mechelen are employees of GSK Biologicals. Dr. Emmanuel Hanon, Dr. Robbert van der Most, and Dr. Marcelle Van Mechelen report ownership of equity or stock options. Dr. van der Most’s spouse is a scientific writer working with GSK Biologicals via a contract research organization.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Philippe Moris and Robbert van der Most contributed equally to this manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Moris, P., van der Most, R., Leroux-Roels, I. et al. H5N1 Influenza Vaccine Formulated with AS03A Induces Strong Cross-Reactive and Polyfunctional CD4 T-Cell Responses. J Clin Immunol 31, 443–454 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-010-9490-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-010-9490-6