Abstract

We investigated individual differences in faking in simulated high-stakes personality assessments through the lens of expectancy (VIE) theory, using a novel experimental paradigm. Three hundred ninety-eight participants (MTurk) completed a “low-stakes” HEXACO personality assessment for research purposes. Three months later, we invited all 398 participants to compete for an opportunity to complete a genuine, well-paid, one-off MTurk job, and 201 accepted. After viewing the selection criteria, which described high levels of perfectionism as critical for selection, these participants completed the HEXACO personality assessment as part of their applications (“high-stakes”). All 201 participants were then informed their applications were successful and were invited to complete the performance task, with 189 accepting the offer. The task, which involved checking text data for inconsistencies, captured two objective performance criteria. We observed faking on measures of diligence and perfectionism. We found that perceived job desirability (valence) was the strongest (positive) determinant of individual differences in faking, along with perceived instrumentality and expectancy. Honesty-humility was also associated with faking however, unexpectedly, the association was positive. When all predictors were combined, only perceived job desirability remained a significant motivational determinant of faking, with cognitive ability also being a positive predictor. We found no evidence that cognitive ability moderated the relations of motivation and faking. To investigate the role of faking on predictive validity, we split the sample into those who had faked to a statistically large extent, and those who had not. We found that the validity of high-stakes assessments was higher amongst the group that had faked.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Supported by overwhelming evidence that describes the associations between personality traits and key work behaviors (Barrick & Mount, 1991; Pletzer et al., 2019; Tett et al., 1991), self-report personality assessments are often used to aid personnel selection (Kantrowitz et al., 2018). Nonetheless, many practitioners and researchers suspect that such measures are susceptible to “faking” behavior by applicants (e.g., Hough & Oswald, 2008; Morgeson et al., 2007). In this context, faking refers to a job applicant adopting a response set that (a) is designed to make a positive impression on a prospective employer, and (b) produces scores on the assessment that are different from his or her true personality scores (Ziegler et al., 2011). It is generally acknowledged that applicants do not all fake to the same extent nor in all application circumstances (Donovan et al., 2003; Robie et al., 2007), and a line of research has been dedicated to try to understand the individual (who) and contextual (when) factors that are most likely to trigger faking. In this study, we contribute to this line of research by examining motivational determinants of faking, through the lens of Vroom’s (1964) expectancy (VIE) theory, as adapted by Ellingson and McFarland (2011).

In addition to the debate about the causes of faking, there is also uncertainty regarding the impact of faking on the validity of self-report assessments. Some have argued that any situationally induced discrepancy between true and observed scores represents a loss of construct validity of the personality measure, and thus, it is assumed that faking would ultimately undermine criterion-related validity (Heggestad, 2011; Mueller-Hanson et al., 2003; Rosse et al., 1998; Tett & Simonet, 2021). By contrast, others have argued that faking, rather than being deceptive, is a form of adaptive self-presentation that is indicative of social intelligence, or a transparent signal that the applicant desires the job. According to this perspective, discrepancies between true and observed scores induced by the selection situation represent signals of better performance at work and therefore criterion-relation validity of the assessment would be unaffected or improved by faking (e.g., Hogan, 2005; Marcus et al., 2020; Morgeson et al., 2007). Others, still, suggest that both mechanisms could feasibly be at play simultaneously in a single sample, potentially yielding no net effect of faking on validity (Marcus, 2009). Altogether, the data necessary to evaluate the effects of faking on criterion validity are scarce and thus researchers often use simulations to estimate the effects of faking (e.g., Converse et al., 2009; Komar et al., 2008). Through this study, we contribute to this line of research by directly measuring faking and task performance from the same sample, allowing for a rare and important investigation of the extent of differential validity attributable to faking.

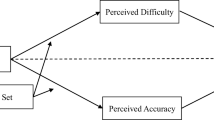

Finally, we note that a vast volume of research into faking, and especially that which seeks to discover the individual and situational determinants of it, has relied on “classical” laboratory designs. In typical applications of these designs, faking is induced by having participants imagine they have applied for a desirable job. As we explain later in detail, these designs help inform questions of how much people can fake but are less useful for examining faking in context. Accordingly, in this investigation, we contribute to the study of faking by introducing an enhanced laboratory design that aims to simulate a job application setting more realistically than classical designs. All hypotheses and the research question are summarized in Fig. 1.

Preamble

Owing to the fact that research on faking has revealed that individuals are very sensitive to the contextual relevance and desirability of certain traits (Dunlop et al., 2012; Hughes et al., 2021), and that the job context can affect the traits on which people fake most of all (Furnham, 1990; Pauls & Crost, 2005; Raymark & Tafero, 2009), it pays to first explain this study’s context and how we expected it to influence the manifestation of faking. In brief, we conducted this study in the context of a crowdsourcing platform, Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk), and designed a competitive application for an opportunity to complete a well-paying task very similar in form to those often completed on MTurk (Schmidt, 2015). Based on our description of the work, we expected that it would activate two facets of conscientiousness (Tett & Burnett, 2003): diligence and perfectionism. Diligence refers to one’s tendency to work hard (Lee & Ashton, 2004) and is arguably relevant to nearly all types of work. Perfectionism refers to one’s attentiveness to detail and, in our study, was signaled clearly as a desired worker characteristic that we would be selecting for. Thus, to operationalize faking, we focused on these two traits. Using faking on these traits, we investigated the motivational determinants of faking as they are described in the VIE theory (Ellingson & McFarland, 2011).

Understanding Individual Differences in Faking Through the Lens of VIE Theory

In seeking to understand the motivational factors that predispose some people to fake more than others, Ellingson and McFarland (2011) undertook a review of the literature focusing on hypothesized individual determinants of faking and integrated their findings using Vroom’s (1964) Expectancy (“VIE”) theory as a framework. These authors noted that faking represents a behavior that, if performed successfully, would be very clearly associated with receiving an extrinsic outcome. Accordingly, VIE theory, which has shown to predict other behaviors in the presence of extrinsic rewards, provides a simplifying framework that integrates the wide variety of specific predictors of faking that have been proposed or studied in the past.

VIE theory draws a distinction between level-one outcomes, namely performance of the behavior (in the context of faking, providing responses to the personality questionnaire that would be seen as desirable by a hiring committee) and level-two outcomes, or the resultant extrinsic reward (receiving a job offer). For an individual applicant to be motivated to fake, as opposed to engaging in an alternative behavior (e.g., respond honestly, withdraw an application) several conditions must be met. First, to satisfy the Valence condition, both the level-one outcome (i.e., providing desirable responses) and the extrinsic reward (i.e., receiving a job offer) must be regarded as more desirable than the alternatives. Second, to satisfy the Instrumentality condition, providing desirable responses must be perceived as somehow conducive to receiving the level-two outcome. Third, to satisfy the Expectancy condition, respondents must believe they are likely to be successful in achieving the level-one outcome (i.e., providing desirable responses). Despite numerous citations, indicating a strong belief in its propositions, the VIE framework has rarely been tested in its entirety with respect to faking on personality assessments (Bott et al., 2010; Komar, 2013). Below, we discuss each of these three conditions separately and present our hypotheses in relation to each individually.

Valence

Valence refers to an outcome’s desirability or the anticipated satisfaction when receiving the outcome, relative to alternative outcomes. At level 2, in the context of a competitive opportunity, valence can be construed as the perceived desirability of that opportunity, where the alternative outcome is one where the opportunity is not granted. In line with this, several models have proposed perceived desirability of a job (the job being the level-two outcome) as a determinant of faking (Goffin & Boyd, 2009; McFarland & Ryan, 2000; Snell et al., 1999). Using VIE theory, Bott et al. (2010) operationalized valence as the perceived desirability of a hypothetical job in a classical lab study of faking, but they did not observe any association of this variable with faking. By contrast, Komar (2013) found that job desirability was a key determinant of the motivation to fake in her first two studies, but, again, it was not associated with actual faking behavior in a third study that used a classical lab design.

Other studies have manipulated valence experimentally. Roess and Roche (2017) found that respondents asked to imagine applying for their “dream” job returned higher scores on the Big Five than those imagining an unattractive job. This study, however, did not include a low-stakes condition (i.e., with “honest” responses), so faking across the job conditions could not be measured directly. By contrast, Dunlop et al. (2015) used a mixed design that included a low-stakes assessment. These authors manipulated valence by contrasting a condition where participants imagined they were unemployed and desperate for work (higher valence) to one where participants imagined they were employed in a satisfactory job and were just testing the market (lower valence). These authors found, however, that this manipulation had only very small effects on faking.

Altogether, it remains somewhat unclear precisely what role that the perceived desirability of a job opportunity plays in motivating faking. Previous lab studies may have yielded conflicting evidence because perceptions of job desirability are often induced through hypothetical situations that are perhaps difficult for participants to truly conceptualize. In real job application settings, however, people may have access to multiple job opportunities, and these may vary organically in their desirability when compared to the opportunities portrayed in typical lab studies. Accordingly, we followed the lead of the VIE model and, using perceived job desirability as a direct measure of level 2 valance, proposed:

-

H1a: Perceived job desirability is positively associated with faking on the diligence and perfectionism scales.

In addition to the extrinsic outcome, VIE theory proposes that valence evaluations are also pertinent to the level 1 behavior. For some, responding to a personality questionnaire in a desirable manner rather than genuine way may be inherently less satisfying than it is for others. Although valence in this respect has been captured in lab studies involving hypothetical job applications (McFarland & Ryan, 2006) accurately capturing, during a real job application, applicants’ perceived desirability of faking is likely to be difficult to achieve. Thus, instead of directly measuring valence of faking, researchers have examined stable traits relating to moral character, namely integrity, personal ethics, honesty-humility, and (low) Machiavellianism that authors consider to be plausible indicators of the proclivity to view faking as relatively less desirable (Ellingson & McFarland, 2011; Goffin & Boyd, 2009; Roulin et al., 2015; Snell et al., 1999). Empirical research using classical lab studies has revealed mixed evidence regarding the role of these moral traits in driving faking. In an early investigation of individual differences in faking, McFarland and Ryan (2000) observed a negative association of faking-good with participants’ integrity. Similarly, honesty-humility was found by J.A. Komar (2013) to be negatively correlated with faking intentions. Bott et al. (2010), however, did not observe an association of integrity with participants’ trait score elevations for a hypothetical job application assessment, and Schilling et al. (2020), using a similar classical lab design, also did not find associations with honesty-humility with faking. Further, more recently, in a study of real applicants to fire-fighter jobs who participated in a research project 3 months after their applications, Holtrop et al. (2021) did not observe a relation of faking in the job application with honesty-humility; however, we note that very little faking was observed in that study overall. Nonetheless, following the VIE model, here we examined whether those with a greater trait-like proclivity to deceive were more motivated to fake and test the following hypothesis:

-

H1b: Honesty-humility is negatively associated with faking on the diligence and perfectionism scales.

Instrumentality

In the context of the present study, instrumentality refers to the respondents’ perceptions that providing desirable responses to a personality questionnaire would be necessary for receiving the job offer. Ellingson and McFarland (2011) proposed that instrumentality perceptions would be higher among respondents who believed that other applicants would be faking their responses. Holtrop et al. (2021) asked their sample of firefighter applicants to estimate the percentage of the applicant pool who had responded completely honestly, managed impressions a little, and outright fabricated their responses to the personality questionnaire that was used for selection. Although these researchers found that this “faking norm” variable was not associated with observed faking, again, there was very little faking observed in their study overall. Thus, in line with VIE theory, here we repeat the endeavor, and hypothesize that:

-

H2a: Participants’ estimates of the proportion of the applicants who respond dishonestly are positively associated with faking on the diligence and perfectionism scales.

In their experimental study, Bott et al. (2010) measured perceived instrumentality more directly by asking participants whether obtaining a high score would increase the chances of being hired, and found that these perceptions were indeed positively associated with faking-good. In our study, we take a similar approach to the measurement of instrumentality and hypothesize:

-

H2b: Perceived instrumentality is positively associated with faking on the diligence and perfectionism scales.

Expectancy

The belief that one can successfully respond to a personality questionnaire in a manner that a hiring committee regards as desirable reflects a respondent’s perceived expectancy. In describing the antecedents of lower expectancy, Ellingson and McFarland (2011) identified characteristics of the assessment processes, including the presence of warnings (Dwight & Donovan, 2003; Fan et al., 2012), and of the assessment itself, such as forced-choice response formats (Cao & Drasgow, 2019). Indeed, both sets of characteristics have been shown to be very effective tools for reducing the prevalence of faking behavior. In this investigation, however, we were interested in observing individual differences in, rather than situational determinants of, expectancy and therefore used a single-stimulus assessment format (i.e., one such as a Likert scale where respondents answer each item, or stimulus, independently), without any warning, to maximize the opportunity for these individual differences to manifest. Accordingly, we measured expectancy perceptions directly, hypothesizing the following:

-

H3a: Perceived expectancy is positively associated with faking on the diligence and perfectionism scales.

We also examined a facet of trait self-monitoring as a stable indicator of expectancy. Self-monitoring describes the extent to which individuals observe and adjust their own behavior in response to situational demands or social appropriateness (Snyder, 1974). In the context of applying for work, individuals who are adept at self-monitoring are thought to recognize the way they portray themselves to the hiring organization and adjust their responses to create a strong impression (Ellingson & McFarland, 2011; Goffin & Boyd, 2009; Marcus, 2009). Studies using classical lab paradigms have found weak positive associations with faking and self-monitoring (e.g., McFarland & Ryan, 2000; Raymark & Tafero, 2009). We are not aware of any field study that has examined self-monitoring as a predictor of faking. In line with the approach of Raymark and Tafero (2009), we focused on a narrower facet of self-monitoring, in this case, the perceived ability to modify self-presentation (henceforth abbreviated to “self-presentation”). This facet captures individuals’ self-assessed ability to adjust their behavior strategically; the very essence of faking. As it is framed as a perceived ability, we position it as an indicator of expectancy, and hypothesize that:

-

H3b: Perceived ability to modify self-presentation is positively associated with faking on the diligence and perfectionism scales.

Ability to Fake

While the VIE factors described above are expected to determine a person’s motivation to fake, motivation alone may not be sufficient for a person to fake, specifically, in an effective manner. In measurement terms, effective attempts at faking are those that result in respondents increasing their standing on the criterion-relevant personality scales during a high-stakes assessment, relative to their “honest” assessment. Some people that are highly motivated to fake may, however, lack the requisite ability to adopt an effective faking strategy, as opposed to an ineffective one. For example, such an individual might adjust their responses to some items from a desired scale to yield higher scores, but also adjust responses to other items from that scale to yield lower scores. Thus, Ellingson and McFarland (2011; see also Snell et al., 1999) proposed that, in addition to being motivated to fake, faking effectively would require a respondent to possess the requisite ability to identify and select responses to the assessment that are the most desirable. In other words, absent the ability to fake effectively, a high motivation to fake would merely lead to “faked” scale scores that are statistically indistinguishable from honest scale scores or, in particularly ineffective cases, scores that are even lower in desirability than honest scores. Similarly, absent a motivation to fake, very little faking—effective or otherwise—would be expected, notwithstanding a person’s ability.

The role that ability plays in driving faking behavior has been investigated empirically. For example, several studies have suggested that those higher on cognitive ability tend to be better able to identify context-relevant criteria, and fake to these more effectively (Buehl et al., 2019; Geiger et al., 2018; König et al., 2006). Further, a recent meta-analysis by Schilling et al. (2021) investigated the relation of cognitive ability and trait scale scores in situations where people would be expected to fake (in lab studies with faking instructions, and in real job applications). These authors found that people higher on cognitive ability tended to produce more desirable personality profiles (e.g., being more conscientious, emotionally stable) in these assessment situations. Of note, however, was that these associations of ability and personality scores were stronger in lab samples (ρ ranged from 0.161 to 0.249) when compared to field samples (ρ ranged from 0.078 to 0.153).Footnote 1 One possible explanation for the larger effect sizes in the lab samples is that the typical lab study of faking will induce high levels of motivation to fake among participants (e.g., through very explicit instructions to fake or to imagine a highly desirable job; high valence), whereas in field samples, respondents will vary more organically in their motivation. In other words, consistent with an ability × motivation interaction as per VIE theory, the effects of ability on faking are most pronounced when there is little doubt that motivation to fake in a sample is high, but less pronounced when motivation is more varied.

An advantage of the repeated measures design employed in the present study is that it is possible to measure faking directly through score differences, rather than indirectly by examining the desirability of responses in one condition only (Schilling et al., 2021). Thus, here we are able to examine cognitive ability as a moderator of relations between motivation and faking behavior itself. We investigate the moderating role of ability with the different measures of VIE individually through the following general hypothesis:

-

H4: Cognitive ability will moderate the relations of the VIE factors with faking on the diligence and perfectionism scales, such that these relations will be stronger for those with higher cognitive ability.

Impact of Faking on Criterion-Related Validity

Finally, competing theoretical perspectives have suggested that faking will introduce to personality scores criterion-irrelevant (Heggestad, 2011; Tett & Simonet, 2021), criterion-relevant information (Hogan, 2005), or a combination of the two (Marcus, 2009). Several lab studies found that scores collected under simulated job application conditions demonstrated relatively lower criterion-related validity than scores from low-stakes assessments (Bing et al., 2011; Christiansen et al., 2005; Mueller-Hanson et al., 2003). In a field study, Donovan et al. (2014) examined a group of applicants who completed an assessment for both selection and, after being hired, training purposes. They found that some applicants produced substantially higher scores on the selection assessment than the training assessment, and these individuals had lower performance levels than those whose scores were similar in both assessments. Similarly, Peterson et al. (2011) found, in a sample of applicants, that faking on a conscientiousness scale undermined its negative association with a self-reported measure of counterproductive work behaviors.

Nonetheless, other research has revealed evidence that faking can improve the criterion validity of an assessment. Buehl et al. (2019) compared the associations of academic performance and interview ratings collected under two conditions: a simulated application setting, and a low-stakes setting. They found that the “application” interview ratings were stronger predictors of academic performance, and that academic performance was also associated with the extent to which participants enhanced their interview responses from low-stakes to the application condition. Similarly, Huber et al. (2021) observed stronger correlations of some self-reported personality measures with a range of criteria when those measures were administered under conditions where participants were either instructed to fake, or incentivized to do so. In both studies, the authors attributed the higher validity of “faked” scores, compared to “honest” scores to the introduction of cognitive ability content into the constructs being assessed.

Because of the conflicting findings, in this study, we adopt an exploratory approach to investigating how faking affects criterion validity.

Enhancing Faking Research Design

As the theoretical review above suggests, faking is investigated in many ways and the strengths and directions of some effects seem to differ depending on the study’s design. We would argue that the progression of faking theory has been hampered by the challenges inherent to studying the phenomenon in context. For example, classical lab studies of faking involving imagined job application, “fake good,” or a prize for the “best response” manipulations reveal that faking is clearly possible, but not the extent to which, why, nor when it occurs in practice. By contrast, approaches that compare applicant samples to non-applicant samples can provide realistic estimates of the sizes of faking effects (Birkeland et al., 2006), however, these designs rarely allow for theory testing because they often rely on archival applicant data and because between-subjects designs preclude the direct observation of faking.

Because of the limitations of the two above designs, researchers regard within-person field studies as a “gold standard” (Ryan & Boyce, 2006), where assessments are completed by real job applicants under both applicant and non-applicant conditions (e.g., for training, development, or research purposes). Such studies are understandably rare, as collecting additional research data from job applicants is often impossible. Further, the studies where this has been achieved tend to vary considerably on “third” factors such as the length of time between, and order of, the low- and high-stakes assessments, the degree of heterogeneity in the job(s) being applied for in the high-stakes setting, and the nature of the personality instruments. A recent meta-analysis by Hu and Connelly (2021) identified 20 studies using this design. While this study revealed large point estimates of faking on the Big Five dimensions, these estimates were hugely variable, with 80% credibility intervals spanning from 0.75 to 1.80 standard deviation units, suggesting that the variable study features may be important moderators of faking. Additionally, because of practical constraints, researchers working in a field context can very rarely measure the theoretical mechanisms that are thought to drive faking.

Because within-person field studies are difficult to establish and come at a cost of researcher control, the reliance on these gold standard designs constrains theory development. Advancing theories of faking clearly requires methodological innovations that give researchers greater control over extraneous factors, without completely compromising the fidelity of a real selection context. Indeed, an impressive enhancement to the classical lab design was introduced by Peterson et al. (2009). In typical applications of this “enhanced lab” design (e.g., Ellingson et al., 2012), after signing up for a research study and completing a personality questionnaire as part of that, participants would be advised of an opportunity to be assessed for their suitability to undertake a desirable opportunity (e.g., a paid internship). Participants would then have the option to be re-assessed, this time under the guise of a selection situation. Afterwards, participants would be informed that the job application was bogus, though manipulation checks in these studies suggest that participants generally perceived the opportunity as legitimate. Thus, at the cost of introducing deception, this design appears to greatly improves the fidelity of the job application assessment conditions.

In our investigation, we introduce improvements to Peterson et al.’s (2009) enhanced lab design and investigate motivational causes of faking and its effects on validity. Specifically, we first assessed the personalities of MTurk workers under research conditions (i.e., low-stakes). Three months later, a much larger time gap than is typically seen in lab studies using this approach, we invited these same participants to apply for a legitimate competitive opportunity to complete a rare but well remunerated MTurk task. In doing so, we informed them we would be assessing their suitability for the task using a personality assessment, which they would then complete (i.e., high-stakes). In contrast to other lab-based approaches, we also then selected all the applicants and invited them to complete this highly paid task, and in doing so, measured their task performance. According to our thinking, this design offers an improved trade-off between the lab and the field: It closely mimics gold standard within-person field-studies but circumvents the dependency on rare and limited opportunities in the field, thus affording researchers a high degree of agency in progressing knowledge about faking and its causes. The design is also easily modified to investigate alternative theoretical perspectives and assessment types.

Method

This study employed a within-subjects design comprising three phases: “low-stakes” assessment condition, “high-stakes” assessment condition, and “performance.” All data, materials, and supplemental analyses are available for download from this project’s OSF page (https://osf.io/bewy3). The project was granted ethical approval by the Human Research Ethics Office of the University of Western Australia approval number RA/4/1/9002, project title “Measuring Impression Management Behavior in Personality Assessments in a Simulated Selection Situation.”

Procedure

US residents were recruited in April 2017 using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) via TurkPrime (now CloudResearch; Litman et al., 2016). In the low-stakes phase, 401 participants completed five items that asked about their motivation to do work on MTurk, a cognitive ability test, a personality questionnaire, and self-monitoring scale in return for US$5. In this phase, participants were informed that the research was “investigating individual differences.” There was no mention of the forthcoming two phases. Instead, participants were informed that they could be invited to participate in future data collections, and that they could opt out if they wished; three did so.

In July 2017, 3 months after the low-stakes phase completed, the 398 participants who did not opt out of future contact were invited via TurkPrime to participate in the high-stakes phase. These participants were not made aware, however, that the invitation was contingent on having participated in the low-stakes phase; as far as they knew, this phase was open to all. The instructions to participants, shown in Fig. 2, were carefully written to portray a legitimate, competitive selection situation. The opportunity described a once-off, high-paying task on MTurk that we needed people to complete. We explained in the instructions that we would be evaluating all applicants against selection criteria and would invite the most suitable applicants to complete this task. The advertised pay for this opportunity was US$12 for 30 min of work, roughly 12 times the median hourly rate of pay on MTurk as estimated by Hara et al. (2018), and accordingly, we expected participants to be motivated to be selected. Altogether, the high-stakes condition ostensibly represented a legitimate competitive job application, albeit for a one-off task rather than ongoing work. Additionally, the participants were compensated US$2 for the time invested in completing their application assessments. Participants who applied completed a personality questionnaire and a short survey asking them about their attitudes towards the selection process.Footnote 2

Altogether, 201 of the original 398 participants completed the high-stakes assessment. Given that the participants had no reason to expect us to approach them a second time, and that 3 months had passed, we expected a high attrition rate. Aside from age and years in full-time work (final participants were older and had accumulated more full-time work), comparisons on all measured demographic variables and individual differences (personality and cognitive ability) revealed no significant differences between those who did and did not apply for the job.

Finally, three weeks after the high-stakes phase, all 201 applicants who completed the job application phase were contacted via TurkPrime to inform them that their application was successful, and they could now access the performance task they had applied for. After accessing the task, participants were informed that the researchers needed human judges to correct some automatically digitally coded handwriting. Participants completed a practice item and then the performance task. In total, 193 participants completed the task, however, data from four participants were excluded, leaving a final study sample of 189.Footnote 3

Participants

Among the final 189 participants, 52.9% were women and the mean age was 38.6 years (SD = 11.2). The mean years of formal education was 15.2 (SD = 2.3) and the mean years of full-time work experience was 16.1 (SD = 11.0).

Measures

Motivation to Complete Tasks on MTurk

For a manipulation check, during the low-stakes phase, we asked participants to report on the extent to which five factors (kill time, make money, have fun, enjoy interesting tasks, and gain self-knowledge) motivated them, using a 4-point scale from not at all to a very great extent.

Cognitive Ability

To measure general cognitive ability in the low-stakes phase, the 16-item sample International Cognitive Ability Resource (ICAR) test was used. The test is presented in the supplement of Condon and Revelle (2014), and includes four items of four types: number sequence, letter sequence, three-dimensional rotation, and matrix reasoning. We observed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78, slightly lower than that reported by Condon and Revelle (alpha = 0.81).

Personality

The 192-item HEXACO personality inventory revised (HEXACO-PI-R) was used to measure participants’ personalities in both the low- and high-stakes phase (Lee & Ashton, 2004). This measure comprises 24 facet scales (8 items apiece) that combine to form measures of the six major HEXACO dimensions (32 items apiece). Full psychometric information for each facet and dimension scale is provided in the online supplement.

Perceived Ability to Modify Self-Presentation

In the low-stakes phase, participants responded to seven items from Lennox and Wolfe’s (1984) perceived ability to modify self-presentation (henceforth “self-presentation”) revised self-monitoring scale (e.g., “In social situations, I have the ability to alter my behavior if I feel that something else is called for.”). Participants responded on a six-point response scale ranging from certainly, always false to certainly, always true. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.92.

Job Desirability, Instrumentality, Expectancy

Following the personality questionnaire in the high-stakes phase, participants were asked for some candid feedback regarding our use of self-report assessments to identify high-quality workers on the MTurk platform. In line with Bott et al. (2010), we adapted items from the test-taking expectancy motivation sub-scale, first presented by Sanchez et al. (2000), to assess job desirability (three items), and directly measure both instrumentality and expectancy (two items each). Examples include, “The opportunity to do the MTurk job is a desirable one for me” (job desirability, alpha = 0.82), “I feel I have a good chance of being hired if the research team likes my answers on the personality questionnaire.”, instrumentality, alpha = 0.53), and, “I am confident that I could get a good score on the personality questionnaire if I tried hard” (expectancy, alpha = 0.87). Participants responded to these items on a five-point strongly disagree–strongly agree scale.

Faking Norms

Finally, in the high-stakes phase, participants were asked to allocate 100 points according to their estimate of the percentage of the other applicants they believed would do the following when completing the personality assessment: (a) respond honestly, (b) try to make a good impression on some aspects of their personality, and (c) focus only on making a good impression. We operationalized faking norms as the number of points assigned to the third category.

Faking

The extent of faking was quantified through regression adjusted difference scores (RADS; Burns & Christiansen, 2011), which were first calculated for diligence and perfectionism separately. RADS for a scale are derived by regressing the high-stakes scale scores onto their low-stakes counterparts and saving the standardized residuals. We then constructed a faking composite, formed by the mean of the two RADS (alpha = 0.73).

Task Performance

In the performance phase, participants completed a checking task that required them to compare hand-written text to computer-coded text and identify any discrepancies (see Fig. 3 for an example). Participants inspected a total of twenty-five stimuli, one at a time, for errors. Each stimulus included 10 hand-written ID numbers juxtaposed against computer-encoded ID numbers, and participants were asked to identify the errors by clicking on the region in the computer-encoded text that contained an error. Of the twenty-five stimuli, five contained zero errors, seven contained one error, seven contained two errors, and six contained three errors. The order in which the stimuli were presented to each participant was randomized. Performance was operationalized through the total number of “misses” (errors not identified, 39 maximum possible) and “false alarms” (non-errors flagged as errors). The mean number of misses (M = 2.35, SD = 2.88) and the mean number of false alarms (M = 0.74, SD = 1.05) were low.

Results

Manipulation Checks

We first sought to verify that an opportunity to complete a highly paid task on MTurk would be coveted by MTurk workers and found that making money was rated as the strongest of the five reasons we examined (M = 3.65 out of 4; 94% selected moderate or very great extent). The next most highly rated reason was to complete interesting tasks (M = 2.57; 52%). Second, using paired-samples t tests we sought to verify that the diligence and perfectionism scales were indeed faked to a significant extent in the high-stakes condition. Diligence in the low-stakes condition exhibited a mean of 3.65 (SD = 0.70) whereas in high-stakes, the mean was significantly higher (M = 3.82; SD = 0.64; Mdif = 0.167, SDdif = 0.53, t(188) = 4.37, p < 0.001, Cohen’s dz = 0.32). Similarly, the mean low-stakes perfectionism score was 3.72 (SD = 0.63) whereas in the high-stakes condition, the mean was significantly higher (M = 3.97, SD = 0.62; Mdif = 0.251, SDdif = 0.51, t(188) = 6.82, p < 0.001, Cohen’s dz = 0.50). Next, we inspected the elevations of the remaining 22 HEXACO facets and full information is available in the online supplement. In brief, we found significant score elevations on seven additional facets; however, the point estimates of all elevations were smaller in size than those of diligence and perfectionism (Cohen’s d ranged from − 0.10 to 0.30, M = 0.08, SD = 0.05).Footnote 4 Additionally, the test–retest correlations of diligence (r = 0.69) and perfectionism (r = 0.67) were the lowest of all facets (range of the remaining facets: 0.73 to 0.88, Fisher-transformed mean r of 0.83). Thus, we concluded that (a) a well-paying opportunity would likely have appealed to the MTurk participants, and (b) the diligence and perfectionism facets were indeed viewed as selection criteria by the participants when in the high-stakes assessment condition.

Individual Differences in Faking

In testing H1-4, we used the diligence and perfectionism RADS composite as a measure of faking. We first examined the descriptive statistics and intercorrelations among the predictors of faking, which are shown in Table 1. We found that gender was associated with faking and with several hypothesized predictors of it. We also noted that age correlated significantly with several of the hypothesized predictors of faking. Accordingly, in our analyses of combined predictors, we controlled for both gender and age. We also control for cognitive ability in anticipation of examining it as a moderator variable to test H4.

Overall, perceived job desirability was very high in this sample (M = 4.56, SD = 0.53). Regarding the relation of valence and faking, we found job desirability was positively associated with faking (r = 0.37, p < 0.001) whereas, surprisingly, honesty-humility was also positively associated with faking (r = 0.21, p = 0.005). Thus, H1a was supported but H1b was not. Model 2 in Table 2 shows the combined relation of valence antecedents and faking, and altogether they explained 13% of additional variance over the control variables. Only job desirability remained statistically significant, however.

To explore why honesty-humility was a positive correlate of faking (r = 0.21, p = 0.005), we inspected the relations of the low-stakes honesty-humility facets and faking. We discovered that the modesty facet was driving this relationship, showing a correlation of 0.28 (p < 0.001); we return to this in the Discussion.

With respect to the instrumentality antecedents, we did not observe a substantial relation of faking norms with faking (r = − 0.03, p = 0.679), however, the perceived instrumentality measure was positively associated with faking (r = 0.16, p = 0.027). Thus, H2a was not supported but H2b was. In combination (model 3 in Table 2), the two antecedents did not explain significant additional variance in faking over the control variables, and neither predictor was statistically significant (the p value for perceived instrumentality was 0.054).

We found that the direct measure of expectancy was significantly associated with faking (r = 0.15, p = 0.036), supporting H3a. Self-presentation, however, was not (r = 0.06, p = 0.405); thus, H3b was not supported. When the two expectancy antecedents were combined (model 4 in Table 2), the direct measure of expectancy remained statistically significant, with the overall model explaining an additional 3% over the control variables.

Finally, we examined a model with all six VIE antecedents combined, with the results shown in Table 2 (model 5). This analysis revealed that the valence antecedents were most strongly associated with faking behavior.

Moderating Role of Cognitive Ability

Although cognitive ability was significantly and negatively associated with both instrumentality (r = − 0.19, p = 0.008), and expectancy (r = − 0.24, p = 0.001), it was not a significant zero-order correlate of faking (r = 0.09, p = 0.243). Given the association of cognitive ability and gender, we inspected the partial correlation of cognitive ability and faking, controlling for gender, and found that it was larger (partial r = 0.14, p = 0.051), albeit not significant, suggesting confounding by gender may have occurred. Indeed, in all regression models including gender shown in Table 2, cognitive ability emerged as a positive and significant predictor.

To examine cognitive ability as a moderator of the relations of each of the motivational factors with faking behavior (H4), we employed hierarchical regression analyses. In a baseline model (model 5 in Table 2), we included cognitive ability and all the motivational measures as predictors of faking. We then ran six regression models—one model for each motivation measure—with each model including the additional corresponding multiplicative cognitive ability × [motivation measure] term. We standardized all predictors before computing interaction terms. Detailed results are reported in the supplement but, overall, we found no evidence of a moderating effect of cognitive ability, thus H4 received no support. That is, cognitive ability appeared be a positive linear predictor of faking only.

Impact of Faking on Criterion-Related Validity

Finally, we turned our attention to predictive validity. Initially, we inspected the raw correlations (shown in Table 1) of low- and high-stakes-assessed diligence and perfectionism with the two performance indicators: misses and false alarms. Generally, the correlations were very close to zero, with the largest being between high-stakes perfectionism and number of misses (r = − 0.14, p = 0.063). Cognitive ability was a significant negative predictor of both misses (r = − 0.29, p < 0.001), and false alarms (r = − 0.23, p = 0.001), however, controlling for ability did not meaningfully affect the correlations of performance with diligence or perfectionism. Thus, when considering the whole sample, it appears that the two focal personality traits, whether assessed in low- or high-stakes, were not valid predictors of the two criteria.

The analyses above, however, do not provide a test of whether the criterion related validity of the assessments is affected specifically by faking. Accordingly, following the procedure used by other researchers (Donovan et al., 2014; Griffith et al., 2007), we next divided the sample into those participants who had more clearly faked their responses and those who had not. Here, clear “fakers” were defined as anyone whose score on either scale increased by more than 1.96 times the standard error of measurement, estimated using Cronbach’s alpha from the low-stakes assessment. Absent any faking, by chance approximately nine of the 189 participants could be expected to be classified as fakers using this procedure. We discovered, however, that 51 participants fell into this category, with the remaining 138 being classified as non-fakers. We then calculated, separately for the two groups, the correlations of low- and high-stakes diligence and perfectionism with the two criteria. These correlations are shown in Table 3. The results pointed to several trends. First, for the non-fakers, validity was very low, with all correlations very close to zero and many being in the opposite direction than expected. Second, for the fakers, three of the four low-stakes correlations were also very small. Third, for the fakers, all four of the high-stakes correlations exhibited stronger relations in the expected direction compared to their low-stakes counterparts, with the correlation of high-stakes perfectionism and misses reaching statistical significance (r = − 0.34, p = 0.015). Altogether, these results lean towards the interpretation that predictive validity was highest among the sample of fakers’ and the high stakes personality scores.

Discussion

Despite receiving significant theoretical and empirical attention, research into applicant faking behavior and its causes has proven challenging, with the central problem being balancing the trade-off between researcher control and external validity. In this investigation, we introduced a new paradigm to study faking that aimed to combine the control afforded by a “lab” environment while improving the realism afforded by a higher-fidelity simulation of a personnel selection experience. Using this paradigm, we advanced understanding of how motivational factors and ability determine faking, using a VIE theory lens (Bott et al., 2010; Ellingson & McFarland, 2011). Altogether, we found that perceived desirability of the opportunity (in VIE terms, the valence of the level-two outcome) was the strongest predictor of faking, although direct measures of faking expectancy and instrumentality were also positive correlates. Higher-ability participants also appeared to fake to greater extent, however, in contrast to VIE theory, ability did not moderate the effects of the motivational factors. We also examined the effects of faking on predictive validity of personality. We found the strongest evidence for predictive validity among the participants who had faked, giving weight to the interpretation that faking may represent an adaptive response to a situation rather than being a deceptive act. Indeed, in line with this, we found no evidence that people’s perceived ability to modify their self-presentation, nor their expectations about the proportion of others who would fake were associated with faking. Further, and contrary to expectations, we observed a positive association of honesty-humility, and in particular its modesty facet, with faking. We discuss these findings and their implications both in relation to the context of this investigation and for future faking research.

Valence, Instrumentality, and Expectancy of Faking

In seeking to understand how motivation determines faking behavior, we found the strongest evidence for the valence component of VIE. Specifically, we found that the perceived desirability of the opportunity (i.e., valence of the level two outcome) to be the single strongest predictor of faking, and it remained so when placed into a regression model combining all VIE predictors. Perceived desirability of a job has been found to be associated with personality (Komar, 2013) and interview (Buehl & Melchers, 2018) faking intentions, however its relation with faking behavior is somewhat uncertain (Bott et al., 2010; Dunlop et al., 2015; Komar, 2013). We note that the cited investigations all employed classical lab designs to prompt faking, whereas this study suggests that job desirability may be an important determinant of faking in situations where individuals have self-selected into an applicant pool.

With respect to perceived instrumentality, we found the direct measure was a positive correlate of faking, though it did not remain significant when combined with the remaining VIE factors, a finding that was inconsistent with those of Bott et al. (2010). We urge some caution with respect to the latter result, however. First, our direct measure of instrumentality was brief and internal reliability unfortunately suffered as a result. Thus, perhaps a longer measure would have revealed a stronger association with faking. Second, the referent of the instrumentality scale was the whole personality assessment, which included many scales that would reasonably have seemed irrelevant to the context (e.g., aesthetic appreciation). If the perceived instrumentality measure had referred directly to the two focal personality scales, its relations with faking may have been stronger. Because most personality assessments used for selection contain several scales, some of which may not be used for selection decision making, we thought it most appropriate to frame instrumentality with reference to the whole measure. Nonetheless, future researchers could consider assessing instrumentality in relation to specific personality content, much like recent attempts to do so with respect to the ability to identify criteria (Holtrop et al., 2021).

In the context of our study, the indirect measure of instrumentality, namely the participants’ estimate of the base rates or norms around faking was not associated with faking. This pattern was also observed by Holtrop et al. (2021) in their study of real job applicants. In this study, participants’ estimates of how many other applicants would fake strongly showed a very wide range (0–80%). Moreover, the selection ratio for the job was unclear; we did not state how many others were invited for the selection phase and how many would be selected for the task. Combining these facts, participants may have found it difficult to estimate how most other MTurkers would have behaved in relation to this opportunity. Perhaps if a selection process is more plainly competitive, the effect of perceived norms may be related more clearly to faking behavior too.

With respect to expectancy, we found that the direct measure was positively associated with faking but, again, it did not remain a significant predictor of faking in a larger VIE model. Further, perceived self-presentation ability was essentially unassociated with faking. Thus, people’s faking did not appear to be strongly determined by whether people believed they could fake effectively nor whether they could effectively manage their impressions on others generally. These results suggest that expectancy might be most strongly influenced by situational factors such as forced-choice response formats (Cao & Drasgow, 2019) and the presence of preventative warnings (Fan et al., 2012), rather than individual differences.

When considering our operationalization of valence, instrumentality, and expectancy together, we noted that the direct measures of the motivational factors related more clearly to faking behavior. Indeed, compared to the direct measures, our alternative measures to capture valence (honesty-humility), instrumentality (perceived faking norms), and expectancy (perceived self-presentation ability), all showed weaker, non-significant, or unexpected relations. From this, we tentatively conclude that measures that directly reference the behavior or outcome, are likely to better capture respondents’ motivation to fake.

We observed a positive association of cognitive ability with faking, though we note the relation emerged only in models that controlled for age, gender, and the VIE predictors. Indeed, it appeared that gender confounded the relation of cognitive ability with faking in our study. Other research using the same version of the ICAR with a large MTurk sample did not show a gender difference (Merz et al., 2020), and thus, we suspect that the relation we observed was a sampling fluke. The association of ability with faking also emerged in other research (Geiger et al., 2018; Schilling et al., 2021) and most notably in samples where the motivation to fake is manipulated (e.g., laboratory studies with job application instructions) rather than free to vary organically. However, cognitive ability did not appear to moderate the relations of any of the motivational predictors of faking and faking itself, and thus, in contrast to VIE theory predictions, possessing requisite ability appears from this research not to be a necessary condition for a motivated person to fake effectively (Ellingson & McFarland, 2011). Instead, it appears that ability acts as an independent contributor to effective faking.

The Impact of Faking on Criterion-Related Validity

At the level of the whole sample, neither of the two performance criteria were strongly associated with the low- or high-stakes personality measures that we expected would be activated by the task (Tett & Burnett, 2003). Indeed, the strongest association we observed was a modest negative association with high-stakes perfectionism. Thus, when examining the whole sample, we were unable to conclude whether faking detracts from or enhances validity. When we examined separately, however, the sub-sample of participants who had adjusted their scores substantially in the high-stakes condition, relative to the low-stakes condition (i.e., the “fakers”), we found larger and consistently negative relations of high-stakes diligence and perfectionism scores with both criteria. By contrast, among the “non-fakers” both low- and high-stakes assessments appeared essentially unrelated to the criteria. We acknowledge that it is impossible to prove that any given one of those “fakers” was truly attempting to produce a higher score, nor do we think it is likely that all the “non-fakers” were not trying to fake. We believe, however, that it is fair to consider the former group as faking suspects. Put together, the findings of this study suggest that those who had faked had produced more valid predictor scores in the high-stakes phase than those who had not faked (Huber et al., 2021).

The Nature of Faking

Considering the findings of this investigation in combination, we believe that a reasonable interpretation is that faking, at least in the context of a competitive opportunity to undertake work in a gig marketplace, represents an adaptive situational self-presentation strategy rather than an attempt at deception (Marcus, 2009; Marcus et al., 2020). First, we observed a positive association with faking and honesty-humility, with the driver of that relation being the modesty facet (and not sincerity or fairness, which are conceptually linked with a proclivity for deceptive conduct). In other words, the people who tend to be relatively more unassuming adjusted their scores on diligence and perfectionism to a relatively greater extent in the high-stakes condition. Perhaps modest individuals tend to downplay their diligence or perfectionism in a low-stakes setting, but recognize that in a competitive setting, they must “let go” of their modesty, put on their “worker hats,” and respond accordingly. Indeed, researchers of job interviewees construe this type of behavior as an “honest” form of impression management (cf. Bourdage et al., 2018, 2020). Further, the absence of a relation of faking with self-presentation, perceived faking norms, or (low) honesty-humility is very surprising if working from an assumption that faking is a deceptive act. Finally, the observation that validity was highest among the fakers is also difficult to reconcile with the view that all faking involves deception. Instead, it suggests that the response set being activated in the high-stakes conditions, among those who adopted a response set at all, was generally more diagnostic of behavior necessary to completing the performance task. Nonetheless, honesty-humility is typically theorized to be a negative determinant of faking (opposite to what we found with modesty) and thus we encourage future researchers to conduct further empirical investigations to ascertain its position as a determinant of faking.

Enhanced Faking Research

In reaching the conclusions above, we must recognize several of the important differences between applying for a one-off task on MTurk and applying for an ongoing paid position that may limit their external validity. Indeed, the task we had described in our high-stakes assessment phase was relatively simple and probably familiar in form to many MTurk workers (Schmidt, 2015). Thus, it may be reasonable for the fakers in our MTurk sample, knowing what to expect, to wear their proverbial “worker hats” for a personality assessment and, once more, while completing a 20–30-min task. It raises questions, however, about whether these same mechanisms also be relevant to longer-term employment situations, or in work roles that are magnitudes more complex and require prolonged effort. We suggest that future researchers could glean insights by enhancing this design even further through the repeated measurement of performance over time (Zyphur et al., 2008). However, we recognize that expanding the paradigm to contexts involving with ongoing paid work will remain challenging.

Nevertheless, the prevalence of faking elicited by the present study seems to resemble effect sizes found in field studies, suggesting that this study’s design might enhance ecological validity of experimental faking research. Specifically, across the sample, as intended by the stimuli we presented in the high-stakes assessment phase, we observed the greatest score elevations on diligence and perfectionism, with respective increases from low- to high-stakes of about a third to half a standard deviation of the differences. Compared to meta-analytically estimated effect sizes of faking, the effects observed here were smaller than those observed in classical “directed faking” lab studies (dz = 0.89 for conscientiousness; Viswesvaran & Ones, 1999), similar to those observed in applicant-non applicant comparisons (ds = 0.45 for conscientiousness; Birkeland et al., 2006), and smaller than those observed in applicant within-person studies (corrected dz = 0.72 for conscientiousness; Hu & Connelly, 2021), though we note that the effect sizes from the latter meta-analysis were highly variable.

Limitations and Suggested Future Directions

In addition to the differences noted above with respect to the complexity and permanency of the selection situation we simulated, we also note several other threats to external validity of this study. Although participants reported that earning money is a very strong reason why they complete work on MTurk and that they valued this particular opportunity very highly, knowing that the work opportunity was one-off may have reduced some of the perceived costs of faking (König et al., 2012), potentially inflating the sizes of the faking effects. Nonetheless, we note that reputation for completing good work is vital for online workers who use the MTurk platform to earn an income, as it affects their approval rates and potentially their access to lucrative tasks (Peer et al., 2014). We also contend that with the prevalence of gig work increasing, it would be useful to identify potential predictors of performance in it (Kan & Drummey, 2018; Peer et al., 2014), and mechanisms that may disrupt these predictors’ utilities. Overall, we encourage future researchers to consider adapting our paradigm with alternative performance tasks and/or tasks that are completed multiple times over an extended period to promote consistent and regular activation of the relevant personality traits.

We also must note that our measures of the VIE factors were brief, coming at a cost to reliability, especially with respect to the instrumentality scale. Longer measures of these factors would have provided a more liberal test of their roles as causal determinants of faking, and their interactions with cognitive ability. While we had adapted a well-used measure of VIE in selection contexts (Sanchez et al., 2000), the original measure was developed for police recruits to assess their motivation in relation to a performance test and, thus, several items could not be easily adapted to this context. We therefore encourage researchers to consider developing revised measures of the VIE factors that would apply to a wider range of assessment contexts.

Finally, we also wish to point out that while recruiting from a diverse population of MTurk workers served to improve the representativeness of our study’s sample, in practice, job applicants tend to self-select, and their application decisions are known to be associated with various individual differences including interests, personality, values, education, experience, and many others. Our sample included people who, at a minimum, had used MTurk for three months, and thus may be representative of people who tend to enjoy, or be competent at, checking tasks. Thus, it remains an open question as to whether the sizes of the effects observed here will generalize to other settings. Nonetheless, we are reassured by the fact that our observed faking effect sizes were similar to those observed in the Birkeland et al. (2006) meta-analysis.

Although our design included a lengthy gap between the low- and high-stakes assessment that was intended to ensure that participants’ memory of completing the original assessment would be weak (Burns & Christiansen, 2006), some participants may nevertheless have recalled their responses to their initial assessment and sought to maintain consistency. The absence of a low-stakes–low-stakes control group also prevents us from ruling out other mechanisms such as maturation, though we note that true personality changes tend to be modest during age range studied here (Bleidorn et al., 2013).

Practical Implications

The prevalence of faking seemed to be fairly low in our study, but there were substantial individual differences in faking, meaning that it will affect candidate ranking substantially. Nonetheless, its effect on validity remains uncertain. Our findings lean towards the view that faking often takes the form of authentic contextualized self-presentation, however, they come with the caveat that the study context does not resemble selection for ongoing employment. Thus, we recommend that detecting faking is a useful step towards trying to manage it. Nonetheless, to our knowledge, many methods that have been developed to detect faking are not effective (e.g., Impression Management scales; Tett & Christiansen, 2007), or are not sensitive enough to confidently identify an applicant as a faker (Dunlop et al., 2020). Therefore, as an alternative, practitioners can focus on reducing faking through faker detection warnings (Fan et al., 2012; Li et al., 2021) or designing harder-to-fake assessment formats (Cao & Drasgow, 2019; Roulin & Krings, 2016).

Second, the results of this study suggest that, of the set we examined, motivation was the strongest predictor of faking behavior, and especially the perceived desirability of the job (valence). This result might suggest that highly attractive, persuasive, or desirable job advertisements may serve as a prompt for more faking during a selection process. Similarly, as applicants move through a process and become more invested in a positive outcome, they may be more prone to faking. Accordingly, we suggest to recruiters that fakeable assessments may be best administered at an earlier stage of a selection process.

Conclusion

Overall, we found that faking was most strongly driven by the perceived desirability of the work opportunity and cognitive ability. We found no evidence, however, of additive VIE effects nor interactive effects of ability on faking. Our study also appeared to lend some support to the hypothesis that faking can be a situationally adaptive behavior, leading to improvements in validity, at least in the prediction of performance in the short term. Methodologically, we believe this study’s design represents an advance in the investigation of faking behavior and encourage future researchers to consider using this design for other assessments that also rely on self-reporting, such as situational judgement tests, video interviews, biodata questionnaires, interest inventories, and values assessments. Moreover, this design allows the systematic study of faking-reducing interventions, or faking inducing or faking suppressing contextual factors, in a naturalistic, but still experimental setting.

Notes

We excluded openness from the reported ranges because this trait is a known correlate of cognitive ability.

We made it clear that the responses to these attitude questions would not affect their chances of being selected.

Data were removed from: two participants who did not follow the instructions of the performance task correctly, one participant who requested that their data not be used for research, and one participant who we later discovered had completed their two 192-item personality assessments in under a minute. We also re-ran all analyses after excluding cases that met the criteria specified by Barends and De Vries (2019) for potentially careless responding within the personality questionnaire and Ward et al. (2017) for long strings of similar responses, but the results were not substantively affected.

These summary statistics were calculated after reversing the direction of differences for the Emotionality facets, where higher scores are typically regarded as less desirable.

References

Barends, A. J., & De Vries, R. E. (2019). Noncompliant responding: Comparing exclusion criteria in MTurk personality research to improve data quality. Personality and Individual Differences, 143, 84–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.02.015

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The Big Five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1991.tb00688.x

Bing, M. N., Kluemper, D. H., Davison, H. K., Taylor, S., & Novicevic, M. (2011). Overclaiming as a measure of faking. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 116(1), 148–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2011.05.006

Birkeland, S. A., Manson, T. M., Kisamore, J. L., Brannick, M. T., & Smith, M. A. (2006). A meta-analytic investigation of job applicant faking on personality measures. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 14(4), 317–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2389.2006.00354.x

Bleidorn, W., Klimstra, T. A., Denissen, J. J., Rentfrow, P. J., Potter, J., & Gosling, S. D. (2013). Personality maturation around the world: A cross-cultural examination of social-investment theory. Psychological Science, 24(12), 2530–2540. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613498396

Bott, J., Snell, A., Dahling, J., & Smith, B. N. (2010). Predicting individual score elevation in an applicant setting: The influence of individual differences and situational perceptions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40(11), 2774–2790. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00680.x

Bourdage, J. S., Roulin, N., & Tarraf, R. (2018). “I (might be) just that good”: Honest and deceptive impression management in employment interviews. Personnel Psychology, 71(4), 597–632. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12285

Bourdage, J. S., Schmidt, J., Wiltshire, J., Nguyen, B., & Lee, K. (2020). Personality, interview performance, and the mediating role of impression management. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 93, 556–577. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12304

Buehl, A.-K., & Melchers, K. G. (2018). Do attractiveness and competition influence faking intentions in selection interviews? Journal of Personnel Psychology, 17(4), 204–208. https://doi.org/10.1027/1866-5888/a000208

Buehl, A.-K., Melchers, K. G., Macan, T., & Kühnel, J. (2019). Tell me sweet little lies: How does faking in interviews affect interview scores and interview validity? Journal of Business and Psychology, 34(1), 107–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-018-9531-3

Burns, G. N., & Christiansen, N. D. (2006). Sensitive or senseless: On the use of social desirability measures in selection and assessment. In R. L. Griffith & M. H. Peterson (Eds.), A closer examination of applicant faking behavior (pp. 113–148). Information Age Publishing.

Burns, G. N., & Christiansen, N. D. (2011). Methods of measuring faking behavior. Human Performance, 24(4), 358–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2011.597473

Cao, M., & Drasgow, F. (2019). Does forcing reduce faking? A meta-analytic review of forced-choice personality measures in high-stakes situations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 104(11), 1347–1368. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000414

Christiansen, N. D., Burns, G. N., & Montgomery, G. E. (2005). Reconsidering forced-choice item formats for applicant personality assessment. Human Performance, 18(3), 267–307. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327043hup1803_4

Condon, D. M., & Revelle, W. (2014). The international cognitive ability resource: Development and initial validation of a public-domain measure. Intelligence, 43, 52–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2014.01.004

Converse, P. D., Peterson, M. H., & Griffith, R. L. (2009). Faking on personality measures: Implications for selection involving multiple predictors. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 17(1), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2389.2009.00450.x

Donovan, J. J., Dwight, S. A., & Hurtz, G. M. (2003). An assessment of the prevalence, severity, and verifiability of entry-level applicant faking using the randomized response technique. Human Performance, 16(1), 81–106. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327043HUP1601_4

Donovan, J. J., Dwight, S. A., & Schneider, D. (2014). The impact of applicant faking on selection measures, hiring decisions, and employee performance. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29(3), 479–493. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9318-5

Dunlop, P. D., Bourdage, J. S., & De Vries, R. E. (2015). VIE Predictors of Faking on HEXACO Personality in Simulated Selection Situations 30th Annual Conference for the Society of Industrial and Organizational Psychologists, Philadelphia

Dunlop, P. D., Bourdage, J. S., de Vries, R. E., McNeill, I. M., Jorritsma, K., Orchard, M., Austen, T., Baines, T., & Choe, W.-K. (2020). Liar! Liar! (when stakes are higher): Understanding how the overclaiming technique can be used to measure faking in personnel selection. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(5), 784–799. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000463

Dunlop, P. D., Telford, A. D., & Morrison, D. L. (2012). Not too little, but not too much: The perceived desirability of responses to personality items. Journal of Research in Personality, 46, 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2011.10.004

Dwight, S. A., & Donovan, J. J. (2003). Do warnings not to fake reduce faking? Human Performance, 16(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327043HUP1601_1

Ellingson, J. E., Heggestad, E. D., & Makarius, E. E. (2012). Personality retesting for managing intentional distortion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(5), 1063–1076. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027327

Ellingson, J. E., & McFarland, L. A. (2011). Understanding faking behavior through the lens of motivation: An application of VIE theory. Human Performance, 24(4), 322–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2011.597477

Fan, J., Gao, D., Carroll, S. A., Lopez, F. J., Tian, T., & Meng, H. (2012). Testing the efficacy of a new procedure for reducing faking on personality tests within selection contexts. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(4), 866–880. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026655

Furnham, A. (1990). Faking personality questionnaires: Fabricating different profiles for different purposes. Current Psychology: Research and Reviews, 9(1), 46–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02686767

Geiger, M., Olderbak, S., Sauter, R., & Wilhelm, O. (2018). The “g” in faking: Doublethink the validity of personality self-report measures for applicant selection. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2153–2153. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02153

Goffin, R. D., & Boyd, A. C. (2009). Faking and personality assessment in personnel selection: Advancing models of faking. Canadian Psychology, 50(3), 151–160. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015946

Griffith, R. L., Chmielowski, T., & Yoshita, Y. (2007). Do applicants fake? An examination of the frequency of applicant faking behavior. Personnel Review, 36(3), 341–355. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480710731310

Hara, K., Adams, A., Milland, K., Savage, S., Callison-Burch, C., & Bigham, J. P. (2018). A data-driven analysis of workers’ earnings on amazon mechanical turk. Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems

Heggestad, E. D. (2011). A conceptual representation of faking: Putting horse back in front of the cart. In M. Ziegler, C. MacCann, & R. D. Roberts (Eds.), New perspectives on faking in personality assessment (pp. 87–101). Oxford University Press Inc.

Hogan, R. T. (2005). In defense of personality measurement: New wine for old whiners. Human Performance, 18(4), 331–341. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327043hup1804_1

Holtrop, D., Oostrom, J. K., Dunlop, P. D., & Runneboom, C. (2021). Predictors of faking behavior on personality inventories in selection: Do indicators of the ability and motivation to fake predict faking? International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 29(2), 185–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12322

Hough, L. M., & Oswald, F. L. (2008). Personality testing and industrial organizational psychology: Reflections, progress, and prospects. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 1(3), 272–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-9434.2008.00048.x

Hu, J., & Connelly, B. S. (2021). Faking by actual applicants on personality tests: A meta-analysis of within-subjects studies. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 29(3–4), 412–426. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12338

Huber, C. R., Kuncel, N. R., Huber, K. B., & Boyce, A. S. (2021). Faking and the validity of personality tests: An experimental investigation using modern forced choice measures. Personnel Assessment and Decisions, 7(1), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.25035/pad.2021.01.003

Hughes, A. W., Dunlop, P. D., Holtrop, D., & Wee, S. (2021). Spotting the “ideal” personality response. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 20(1), 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1027/1866-5888/a000267

Kan, I. P., & Drummey, A. B. (2018). Do imposters threaten data quality? An examination of worker misrepresentation and downstream consequences in Amazon’s Mechanical Turk workforce. Computers in Human Behavior, 83, 243–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.005

Kantrowitz, T. M., Tuzinski, K. A., & Raines, J. M. (2018). Global assessment trends report 2018. https://www.shl.com/en/assessments/trends/global-assessment-trends-report/

Komar, J. A. (2013). The faking dilemma: Examining competing motivations in the decision to fake personality tests for personnel selection University of Waterloo]. https://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.item?id=TC-OWTU-7697&op=pdf&app=Library&is_thesis=1&oclc_number=860777893

Komar, S., Brown, D. J., Komar, J. A., & Robie, C. (2008). Faking and the validity of conscientiousness: A Monte Carlo investigation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 140–154.

König, C. J., Melchers, K. G., Kleinmann, M., Richter, G. M., & Klehe, U.-C. (2006). The relationship between the ability to identify evaluation criteria and integrity test scores. Psychology Science, 48(3), 369–377.

König, C. J., Merz, A.-S., & Trauffer, N. (2012). What is in applicants’ minds when they fill out a personality test? Insights from a qualitative study. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 20(4), 442–452. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12007

Lee, K., & Ashton, M. C. (2004). Psychometric properties of the HEXACO personality inventory. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(2), 329–358. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3902_8

Lennox, R. D., & Wolfe, R. N. (1984). Revision of the Self-Monitoring Scale. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(6), 1349–1364. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.46.6.1349

Li, H., Fan, J., Zhao, G., Wang, M., Zheng, L., Meng, H., Weng, Q. D., Liu, Y., & Lievens, F. (2021). The role of emotions as mechanisms of mid-test warning messages during personality testing: A field experiment. Journal of Applied Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000885

Litman, L., Robinson, J., & Abberbock, T. (2016). TurkPrime.com: A versatile crowdsourcing data acquisition platform for the behavioral sciences. Behavior research methods, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-016-0727-z

Marcus, B. (2009). ‘Faking’ from the applicant’s perspective: A theory of self-presentation in personnel selection settings. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 17(4), 417–430. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2389.2009.00483.x