Abstract

Compassion is in high demand within organizational research, with important implications for leadership, well-being, and productivity. However, thus far only meditation-based interventions have been implemented to increase compassion in organizations. Our aim was to explore whether compassion could be increased among managers through improving their emotional skills. We implemented a quasi-randomized controlled trial with pre-test and post-test design of a new emotional skills cultivation training among managers, measuring the treatment group (N = 68), the control group (N = 90), and their followers (N = 85 and N = 72). Compared to the control group, the managers exhibited significantly increased sense of emotional skills, with some evidence for an improved sense of compassion. We also found that emotional skills mediated the impact of participating in the intervention group and compassion. Additionally, servant leadership behaviors in the intervention group improved following the intervention. These results demonstrate that instead of being something innate, compassion is a skill that can be increased through training emotional skills, with observable benefits for the organization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

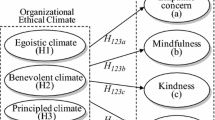

Compassion—defined as an interpersonal process involving the noticing, feeling, acting, and sense-making that alleviate the suffering of another person (Dutton, Workman, & Hardin, 2014)—is in high demand in today’s workplace. Traditionally, emotions, particularly the management of negative emotions, have been neglected in organizational life (Zineldin & Hytter, 2012). An increasing amount of burnout and stress, low levels of employee engagement, pain and suffering spilling over from employees’ personal lives, constant changes, and increasing demands with less resources have, however, made compassion an important and timely, but difficult, challenge for organizations and for leadership. Recently, organizational and leadership studies have called for more research on compassion-related topics, including mindfulness in leadership (Nübold, Van Quaquebeke, & Hülsheger, 2019) as well as organizational concern and ethical leadership (Lu, Zhou, & Chen, 2018).

A growing body of research has begun to document the many positive impacts of compassion on organizations (e.g., Dutton, Lilius, & Kanov, 2007; Lilius, Worline, Dutton, Kanov, & Maitlis, 2011; Tsui, 2013) and the fundamental role that compassion plays in human interrelating (e.g., De Waal, 2009; Keltner, 2009). For instance, compassion in organizations has been associated with improved cooperation and trust (Dutton et al., 2007), a more prosocial identity (Grant, Dutton, & Rosso, 2008), and increased sense of worth and value (Frost, 2003; Frost, Dutton, Worline, & Wilson, 2000). In an IT firm, compassionate meditation practice improved employees’ daily experiences of positive emotions, which in turn impacted purpose in life, mindfulness, social support, illness symptoms, life satisfaction, and depressive symptoms (Fredrickson, Cohn, Coffey, Pek, & Finkel, 2008). Moreover, among public service employees, a longitudinal study showed that compassion from supervisors positively predicted future work engagement, organizational citizenship behavior, client-rated service-oriented performance, and decreased job burnout (Eldor, 2017). Compassionate behavior has also been associated with increased attachment and commitment to one’s organization and with lower turnover rates (Grant et al., 2008; Lilius et al., 2008). Also, acting compassionately has been related to others perceiving one’s leadership capability and intelligence as higher (Melwani, Mueller, & Overbeck, 2012). Moreover, an organizational culture of companionate love—a more stable disposition of feeling affection, compassion, caring, and tenderness for others (Reis & Aron, 2008)—has been associated with increased job satisfaction and better teamwork and less absenteeism and emotional exhaustion (Barsade & O’Neill, 2014). These studies suggest that there is much potential in compassion training for enabling more humane and successful work life and leadership.

Today, several meditation-based compassion training programs have been developed and studied outside occupational settings among various clinical populations (Gilbert, 2009; Jazaieri et al., 2012; Kirby, Tellegen, & Steindl, 2017; Neff & Germer, 2013). These intervention studies have illustrated that compassion can be increased leading to other positive outcomes such as increased positive emotions, social support, and purpose in life, as well as decreased illness symptoms, depression, and self-criticism (e.g., Fredrickson et al., 2008; Gilbert & Procter, 2006; Kirby et al., 2017).

Despite an increasing number of studies suggesting positive effects of compassion in organizations and success of compassion interventions in clinical samples, surprisingly little is known about how compassion could be increased in organizations through interventions. In this study, our aim is to examine whether compassion could be strengthened by learning emotional skills. For this purpose, we developed a new emotional skills cultivation training (ESCT) intervention and set out to assess its impact among managers in order to enrich the understanding of the ways compassion could be increased in organizations. In particular, we were interested in whether increasing managers’ emotional skills would increase their sense of compassion as well as their ability to be servant leaders and support the autonomy of their subordinates.

Promoting Compassion in Organizations

Thus far the few intervention studies carried out in organizations to foster compassion have focused on meditation (Fredrickson et al., 2008; Scarlet, Altmeyer, Knier, & Harpin, 2017). However, meditation may not always be well-suited for everyone or fit well to the everyday constraints of organizations without appropriate resources in terms of professional guidance, flexibility in matching an employee with right kind of meditation, and skillful management of possible challenging or harmful experiences (Lindahl, Fisher, Cooper, Rosen, & Britton, 2017). Thus, it would be highly valuable to develop and test other types of interventions that potentially could increase compassion in organizations, ones that are non-meditation based, as is the case in the present study.

Moreover, previous organizational compassion interventions have focused on employees as opposed to those in managerial roles (Fredrickson et al., 2008; Scarlet et al., 2017). A particular focus on strengthening managers’ compassion could, however, be important for three reasons. First, it has been suggested that managers’ behaviors are especially important in facilitating compassion in organizations through modeling the appropriateness of compassionate responses (Dutton et al., 2014). Second, managers are likely to have a higher sense of power in organizations than followers, which can lead managers to experience less distress and less compassion (Van Kleef et al., 2008). Third, more compassionate managers could be more sensitive to the needs of their followers, making them more autonomy supportive and servant leadership-oriented, which have both been associated with various positive effects for employees such as increasing their autonomous motivation, engagement, and commitment to the organization (e.g., Otis & Pelletier, 2005; Van Dierendonck, 2011).

Given the suggested benefits of compassion in organizations, there is a clear need to learn more about the different ways compassion could be increased in organizations. Accordingly, to our best knowledge, our study presents the first non-meditation-based intervention study to investigate whether compassion could be increased in organizations among managers through increasing their emotional skills with a new in-depth emotional skills cultivation training. In summary, this study adds to the previous research in three ways: (1) It focuses on the organizational context instead of general or clinical populations, (2) instead of being based on meditation, our study aims to enhance compassion by improving emotional skills, and 3) while the few previous meditation-based compassion intervention studies in organizations have focused on employees, the current study focuses on managers.

It is worth noting that compassion has been defined in many different ways in various research fields and is sometimes treated as an emotion (see Goetz, Keltner, & Simon-Thomas, 2010; Singer & Klimecki, 2014), but our treatment of compassion follows the paradigm in the organizational arena, where it is conceptualized not as an emotion but instead as a social process including the four steps of noticing, feeling, acting, and sense-making (see, e.g., Dutton, 2006; Dutton et al., 2014; Guinot, Miralles, Rodriquez-Sanchez, & Chiva, 2020; Kanov, Powley, & Walshe, 2016; Lilius et al., 2011; O’Donohoe & Turley, 2006).

The Importance of Emotional Skills for Compassion

In their review of emotional skills trainings, Satterfield and Hughes (2007) refer to the definition of emotional intelligence—awareness, understanding, and management of emotions in the self and others—(Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2000) to categorize emotional skills as the teachable set of cognitive and behavioral strategies (e.g., making empathic statements, de-escalating an angry client, challenging cognitive assumptions, or making soothing statements) that facilitate emotional awareness, understanding, and management of emotions in the self and in others, including attitudes, knowledge, and skills. Emotional skills thus make the person better able to understand and manage one’s own emotions as well as more capable of detecting emotions in others and navigate in emotionally charged situations. Our thesis here is that these varied emotional skills are important contributors to the social process of compassion. Compassion, as noted, involves four sub-processes: the noticing, feeling, acting, and sense-making (Dutton et al., 2014), which all, as we argue below, can be strengthened through certain emotional skills. Accordingly, we believe that a person’s sense of compassion could be improved through improving that person’s emotional skills. While a person’s ability to act compassionately might be dependent on various contextual factors as well as personality attributes, we argue that emotional skills are one key antecedent leading to more compassionate action. Below we elaborate on our thesis by examining how emotional skills could positively contribute to each of the four sub-processes of compassion.

First, the noticing of suffering takes place when one becomes aware of someone’s suffering. The awareness of another’s suffering might be obvious or more effortful depending on the clarity of the pain cues (Dutton et al., 2014). In work contexts, these cues might often be ambiguous (Frost, 2003). To follow the definition of emotional skills discussed above, the more skillful one is in one’s emotional skills such as emotional awareness and understanding, and the more likely one is to notice someone’s pain cues. For example, the more elaborated an emotional vocabulary one has, the more likely one is to understand the subtle differences in one’s own and others’ emotional cues (Kashdan, Barrett, & McKnight, 2015).

Second, the feeling most closely associated with compassion is empathic concern, which means “other-oriented feelings that are most often congruent with the perceived welfare of the other person” (Batson, 1994, p. 606). Empathic concern is said to be the motivator of prosocial thoughts and actions (Batson, 1994; Jordan, Amir, & Bloom, 2016). Sometimes feeling what others feel (affective empathy) may evoke personal distress instead of empathic concern (Jordan et al., 2016), demonstrating that feeling what others feel is distinct from caring about what others feel. As Jordan et al. (2016) suggest, caring about what others feel is likely to be related to perspective taking and cognitive efforts to understand what others are feeling rather than purely affective empathy. This would suggest that emotional skills defined as cognitive and behavioral strategies that facilitate the understanding and management of emotions in the self and in others could promote empathic concern leading to prosocial actions. For example, better knowledge of how different emotions affect our performance and well-being differently, and how we all strive to manage our emotions to the best of our capabilities in the effort to feel good, could improve our capabilities to care about what others feel.

Third, acting compassionately stands for all the behaviors intended to improve the experience of a person suffering including concrete and more abstract resources such as attention (see Dutton et al., 2014). Sometimes people might have a strong motivation to act compassionately, but refrain, because they simply do not have the necessary skills to address the other in pain, fear, for example, that being compassionate would make them appear weak, or do not know what to do. Indeed, Kanov et al. (2016) have addressed the importance of courage in the face of such obstacles to acting compassionately. The cognitive and behavioral strategies including attitudes, knowledge, and skills to understand and manage emotions are likely to strengthen a person’s sense of competence and courage to act compassionately, when motivated to do so. For example, being able to understand the different meanings and action tendencies related to different emotions or simply to label different emotions might improve the capability to choose the most appropriate emotional strategy (Kashdan et al., 2015).

Fourth, sense-making takes place throughout the process of compassion. It refers to the interpretive work (Weick, 2012) people do to find meaning and understanding to the ambiguity of things (Weick, Sutcliffe, & Obstfeld, 2005). When faced with suffering, people aim to make sense of it in order to understand and decide whether it is worthy of compassion. At least three appraisals—accounts used to explain the causes of suffering to ourselves and others—have been argued to be relevant to compassion (Atkins & Parker, 2012): Does the person suffering deserve help? How relevant is the sufferer or their situation to the one helping? Does the person helping have a sense of self-efficacy? A person is appraised as being more deserving of compassion if they are perceived as morally good character, trustworthy, and altruistic (Atkins & Parker, 2012). A focal actor may also judge whether their own values and goals are congruent with the experiences of the sufferer. Moreover, focal actors may weight out their own abilities to cope with the situation and bring about desired and helpful outcomes (Atkins & Parker, 2012). Accordingly, emotional skills such as being more aware of and understanding our attitudes and other cognitive and behavioral strategies better could help make sense of situations in a way that would facilitate compassion. For example, knowledge of generous interpretations, i.e., appraisals grounded in a positive default assumption of people being good, capable, and worthy of compassion, when suffering (Worline & Dutton, 2017), could strengthen emotional skills that facilitate compassionate sense-making of the unfolding events at work.

Developing an Emotional Skills Cultivation Training

In order to improve participants’ emotional skills, we designed a new emotional skills cultivation training (ESCT) (Table 1). ESCT was designed together with a highly experienced organizational psychologist specialized in emotional skills in organizations, and the contents were grounded in emotion and compassion literature (e.g., Ekman, 2007; Goleman, Boyatzis, & McKee, 2009; Keltner, 2009). Each module taught emotional skills together with teachings of compassionate motivation. The training was taught by the first author of this paper in six 3-h modules spanning over 8 weeks. Each module included literature, discussions, and exercises designed to deliver both didactic and experiential training in emotional skills. In between sessions, the participants were asked to do a homework exercise.

Hypotheses

We considered important to measure expected changes in the participants, but as the true test for positive changes is, whether these changes are also experienced by others, here by the followers of the participating managers, we also included other-rated measures that are relevant indicators for increased compassion. As a guiding framework, we followed existing compassion training studies in which improvements in compassion are considered as increases in the levels of compassion and decreases in the levels of fear of compassion (Gilbert & Procter, 2006; Jazaieri et al., 2012). Accordingly, we expect changes in the participants’ levels of compassion and levels of fear of compassion. Secondly, to test whether the expected changes are also experienced by the followers of the participating managers, we studied existing measures on leaders’ compassionate behaviors. As a result, we chose two other-rated measures on leaders’ behavior that are most relevant indicators for increased compassion, namely, servant leadership and autonomy support. Thus, to test whether our ESCT intervention would have positive impacts, we formulated six hypotheses four of which were self-rated and two other-rated by the followers of the managers.

Our first hypothesis is straightforward: ESCT intervention should improve people’s sense of having emotional skills. Measuring this sense of emotional skills is important in order to validate that the intervention actually improves what it ought to improve, namely, emotional skills. As we outlined above, the intervention mainly aimed to teach participants various emotional skills. Thus, we decided to measure participants’ self-rated emotional skills in order to see whether they themselves experienced any improvement in their emotional skills.

-

Hypothesis 1: ESCT will result in improved self-rated sense of emotional skills.

In the section on the importance of emotional skills for compassion, we already outlined our reasons for why we believe that emotional skills contribute positively to people’s capability to act compassionately. The emotional skills cultivation training (ESCT) developed for this study included elements related to each of the four sub-processes of compassion (Dutton et al., 2014)—the noticing, feeling, acting, and sense-making that alleviate the suffering of another person. The participants engaged in exercises and discussions that aimed to teach them (1) to better notice and be aware of different emotions and suffering in the self and in others, thus supporting the noticing sub-process of compassion; (2) to better understand and care about what others are feeling, thus supporting the feeling sub-process of compassion; 3) to feel more knowledgeable, competent, and courageous to act in various emotionally loaded situations, thus contributing to the acting sub-process of compassion; and (4) to better make sense of emotionally loaded situations, thus contributing to the sense-making sub-process of compassion. As follows, we believe that ESCT should have a positive impact on self-rated compassion among the participants of the training. Furthermore, we believe that a key reason why ESCT has a positive impact on sense of compassion is because the participants’ emotional skills have improved. Accordingly, we predict that any positive relation between the intervention and sense of compassion will be mediated by sense of emotional skills (we acknowledge and thank the editor for suggesting during the review process that we test this mediation).

-

Hypothesis 2. ESCT will result in improved self-rated sense of compassion.

-

Hypothesis 3: The relation between intervention and sense of compassion will be mediated by sense of emotional skills.

Another way to test improvements in compassion is to measure decreases in the levels of fear of compassion (Gilbert & Procter, 2006; Jazaieri et al., 2012). One inhibitive characteristic associated with compassionate behavior is fear of compassion for others, meaning that people may actively resist engaging in compassionate experiences or behaviors (Gilbert, McEwan, Matos, & Rivis, 2011). For example, people might be afraid that exhibiting compassion is too costly or that it could be perceived as a sign of weakness. In general, because compassion is seen as a costly resource to dispense from an evolutionary perspective (Gilbert et al., 2011), people are more likely to be compassionate to people they like or find potential reciprocators of helpfulness (Burnstein, Crandall, & Kitayama, 1994). Especially in competitive environments such as work context, people are at risk of increasing uncaring or exploitative behaviors towards others (Bakan, 2005) rather than compassion, or they might worry compassion means letting people off the hook, or people taking advantage of you (McLaughlin, Huges, Fergusson, & Westmarland, 2003). Thus, acting compassionately in organizations might often be inhibited by a fear of what expressing compassion would entail. We argue that teaching emotional skills could decrease such fears and such active resistance by making people more aware of the ubiquitous presence of emotions in human interactions and the negative consequences of not attending to various negative emotions that employees might be having. Furthermore, through having increasing confidence in one’s ability to address emotionally loaded situations right, one should become less fearful that acting compassionately in such situations might lead to negative consequences for oneself. Thus, even in a competitive environment such as the work organization, we posit:

-

Hypothesis 4: ESCT will result in decreased self-rated fear of compassion.

As we believed that the ESCT would awaken compassion among the participants, we expected the participants to adopt more compassionate ways to interact with their followers. Servant leadership has been suggested to be the leadership theory that most closely emphasizes compassion (Van Dierendonck & Patterson, 2014) as servant leaders are thought to be motivated by a genuine concern for their followers underlining leadership practices related to compassionate concern (Greenleaf, 1977). A servant leader is said to go beyond self-interest with the aim of helping their followers to succeed at work while also growing as humans, that is, to become healthier, wiser, freer, and more autonomous (Greenleaf, 1977). Accordingly, servant leadership has been shown to create better team and leadership effectiveness, organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behavior (Van Dierendonck, 2011).

Van Dierendonck and Patterson (2014) have integrated the concepts of compassion and servant leadership by suggesting that compassionate love—the unselfish moral love that centers on the good of the others (Patterson, 2003)—is the cornerstone of and the underlying motivation to become a servant leader. They theorize that compassionate love promotes virtuous attitude, which in turn fosters servant leader behavior. More specifically, servant leader behaviors have been characterized by many of the strategies and practices taught in the ESC training, such as listening, presence, empathy, courage, authenticity, appreciation of others, and awareness (e.g., Greenleaf, 1977; Van Dierendonck, 2011; Van Dierendonck & Patterson, 2014). Thus, we argue that from the point of view of the followers, the manager’s compassion manifests itself in servant leadership behavior. Accordingly, to examine whether the manager’s compassion has increased not only in their self-perception but also in the perception of their followers, we see it as crucially important to measure servant leadership, as servant leadership behavior can be seen as a key potential outcome of manager’s increased capability for compassion. As follows, we posit:

-

Hypothesis 5: ESCT will result in increased follower-rated servant leadership.

Alongside servant leadership, we expected the participants of the ESCT to adopt increased autonomy support (behavior) as rated by their followers. Autonomy support, like servant leadership, begins with the manager taking the followers’ perspective in relating to their followers and in aiming to support them in their needs (Baard, Deci, & Ryan, 2004). More specifically, autonomy support in work organizations concerns the interpersonal orientation used by a manager (Deci, Connell, & Ryan, 1989) to support the basic psychological needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Ryan & Deci, 2000)—of employees. This kind of autonomy support has been shown to relate to trust, satisfaction (Deci et al., 1989), innovation, and learning (Ryan & Deci, 2000). We assume that the ability to take the followers’ perspective to support these three needs requires compassion and emotional skills. More concretely, in order to support, for example, the need of relatedness, a manager needs to be skillful at strengthening the feelings of being understood and appreciated, highlighting meaningfulness, and encouraging socializing (Reis, Sheldon, Gable, Roscoe, & Ryan, 2000). Taken that ESCT specifically taught related skills such as perspective taking and fostering connection and compassionate giving, we believe that increased autonomy support is another way that the increased emotional skills and compassion of the manager manifest to the employees. Thus, we posit:

-

Hypothesis 6: ESCT will result in increased follower-rated autonomy support.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

We conducted a quasi-randomized controlled trial of a new in-depth emotional skills cultivation training (ESCT) versus a control condition (CC) to test whether compassion could be taught and increased in organizations through emotional skills training. The ESCT was repeated with seven groups. Data was collected from managers through self-reported questionnaires and from their followers in two waves: a week before (T1) and a week after (T2) the training. Participants were managers from five different organizations representing different industries from private and public sectors, including financing and insurance, commercial TV channel, a large art institution, and a large municipality. One ESCT group consisted of 10–20 managers in the treatment group and at least an equivalent number of managers in the control group. Sixty-eight treatment group participants and 90 control group participants answered both the T1 and the T2 questionnaires so that the answers could be matched. Additionally, followers of four of the intervention groups participated in the study. Eighty-five treatment group followers and 72 control group followers answered both the T1 and the T2 questionnaires so that the answers could be matched (Fig. 1). That is, only the answers from those followers who answered the questionnaire at both time points were kept for analysis. Thus, leaders were rated by the same followers at the two time points for analysis. Groups did not differ in terms of gender, age, or ethnicity.

Participants—both managers and their followers—were recruited from the organizations by an open invitation or by an addressed invitation by their supervisor. Four of the seven ESCT groups were randomized with a 50% probability of treatment group or a 50% probability for control group. In the three groups that were not randomized, participants voluntarily enrolled to the training via, for example, the organization’s intranet or they participated out of a suggestion by their manager. The participants were given only a brief brochure of the main practicalities, background, and overall idea of the training. Providing of more information was avoided in order not to potentially influence the pre-questionnaire answers. In accordance with the design of the training, 10–20 participants were enrolled in each treatment group. The specific number of participants depended on the organization and especially on the timing and other resource constraints and the number of available employees with equivalent number of control condition candidates. Due to limited time resources available on behalf of the participant organizations, the study did not include an active control condition, which will be further discussed in the “Limitations and Future Research” section of this paper. While the treatment group participated in the training, the control group only filled out the surveys without receiving any training at that point. In other words, the control condition was passive. After the post-questionnaires had been collected, depending on the resources and willingness of the organization, the control group was given the same training or lectures with similar content. No data, however, was collected from these optional trainings.

As presented earlier, the training taught a wide array of emotional skills with the goal of increasing participant’s understanding and competence to manage emotions in the self and in others in order to better navigate emotionally loaded situations and positively affect one’s own and others’ emotions as well as the emotional climate of the organization. Specifically, the training focused on emotional skills related to strengthening each of the four sub-processes of the social process of compassion, as discussed in the Introduction. ESCT was designed to consist of six 3-h modules as outlined in Table 1, and the modules were designed to be held over an 8 weeks’ time period. The design decision was based on three criteria: first, the contents of the training required six topics; second, the established mindfulness, self-compassion, and loving-kindness compassion interventions were often described as 8-week trainings or to consist of six to eight modules (e.g. Fredrickson et al., 2008; Jazaieri et al., 2012; Neff & Germer, 2013); and third, the design of six 3-h modules enabled the modules to be spread across the 8 weeks so that there would be enough time for the participants to practice their home exercises in between the modules, digest and try out the new tools and learnings of each module in practice in between the modules, and to have enough time for learning during the training, including having several separate time points to meet with the participants in order to remind them of the new learnings.

The six modules included increasing the awareness of emotions at work; understanding the forces behind emotions; increasing and strengthening positive emotions; facing and dealing with negative emotions and difficult situations; leader’s toolkit to lead emotions; and systematically leading the emotional climate of an organization. Each module was built around literature and discussion, and they included in-class exercises, and exercises to be practiced in between modules (see Table 1). For example, module 1 focused on literature and discussions around compassion at work as well as management of emotions, understanding of the meaning and impacts of different emotions, and learning emotional vocabulary. Exercises were built around noticing of different emotions and practice of vulnerability, courage, and curiosity. Home exercises focused on noticing and analyzing emotions at the workplace and practicing curiosity. The contents of the module 1, as well as the contents of the other modules, were linked to the social process of compassion, as described in the Introduction. For example, skills taught in the first module such as noticing emotions, naming emotions, and staying curious of emotional experiences are likely to be important contributors to, for example, noticing of others emotional cues and making sense of others’ emotional experiences in a way that gives way for compassion.

Measures

Self-Rated Measures

Sense of compassion was measured with Santa Clara Brief Compassion Scale (Hwang, Plante, & Lackey, 2008), which is a brief five-item version of Sprecher and Fehr’s (2005) Compassionate Love scale (e.g., “One of the activities that provide me with the most meaning to my life is helping others in the world when they need help”) rated on a seven-point Likert scale (1, Do not agree at all; 7, Completely agree). Of the four sub-processes of compassion, it is most closely associated with the motivational feeling sub-process. In the scale development study, internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) was .90. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was .83.

Sense of emotional skills measure was developed for this study to measure emotional skills. The development of the measure and its psychometric properties will be reported below.

Fear of Expressing Compassion for Others measure (Gilbert et al., 2011) is comprised of 10 items (e.g., “People will take advantage of me if they see me as too compassionate” or “I worry that if I am compassionate‚ vulnerable people can be drawn to me and drain my emotional resources”) rated on a five-point Likert scale (1, Do not agree at all; 5, Completely agree). In the scale development study, internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) was .78. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was .79.

Follower-Rated Measures

Servant Leadership Survey measure (Van Dierendonck & Nuijten, 2011) assesses eight orientations of servant leadership: empowerment, standing back, accountability, forgiveness, courage, authenticity, humility, and stewardship. The measure is comprised of 30 items (e.g., “My manager helps me to further develop myself” or “My manager keeps himself/herself in the background and gives credits to others”) rated on a six-point Likert scale (1, Do not agree at all; 6, Completely agree). The scale development study did not report alpha for the whole scale but only for its sub-dimensions. Subsequent studies have analyzed the validity of the measure (e.g., Hakanen, Harju, Seppälä, Laaksonen, & Pahkin, 2012; Rodriguez-Carvajal, De Rivas, Herrero, Moreno-Jimenez, & Van Dierendonck, 2014; Cronbach’s alpha for the whole measure was = .95 and = .94, respectively). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was .90.

Autonomy Supportive Leadership was measured with scale taken from the Work Climate Questionnaire (WCQ) (Baard et al., 2004) and is comprised of six items (e.g., “My supervisor listens to how I would like to do things” or “I feel understood by my supervisor”) rated on a seven-point Likert scale (1, Do not agree at all; 7, Completely agree). Baard et al. (2004) did not report alpha for the six-item scale, but they reported alphas for the two comparable questionnaires (Williams & Deci, 1996; Cronbach’s alpha = .96; Williams, Grow, Freedman, Ryan, & Deci, 1996; Cronbach’s alpha = .92) used to develop the longer version, that is, the 15-item version of WCQ. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was .95.

Results

Developing the Measure for Emotional Skills

Given that we were unable to identify any measure of emotional skills aligned with our definition of it, we decided we need to develop such a measure ourselves. We initially generated 15 face valid items that aimed to capture various emotional skills people might have related to (1) understanding the importance of emotions, (2) having a sense of ability to influence emotions, and (3) approaching situations with right kinds of emotional strategies. Examining the psychometric properties of these items using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), we dropped five items based on too high modification indices, leading to a final model with 10 items that cover various aspects of emotional skills (e.g. “I understand what emotions are,” “I find that I can affect my own emotions,” and “I feel that I have the means and the ability to face and handle negative emotions at the workplace”) rated on a seven-point Likert scale (1, Do not agree at all; 7, Completely agree). The scale had three subdimensions. To examine their distinctiveness, we performed a confirmatory factor analysis with maximum likelihood using lavaan package in RStudio 1.0 to compare a model where all items were part of one large factor (χ2 (df = 35) = 178.28, CFI = .82, TLI = .76, RMSEA = .16, SRMR = .13), and another model with three latent variables together comprising a higher-level factory (χ2 (df = 32) = 48.24, CFI = .98, TLI = .97, RMSEA = .06, SRMR = .04). The latter had satisfactory psychometric properties, thus demonstrating that there are three subscales within the emotional skills scale. Nevertheless, as we did not have separate predictions for the subscales and were interested in emotional skills in general, we decided to use the aggregate scale in further analyses. The Cronbach’s alpha for this final scale was .85. To assess construct validity, we expected emotional skills to correlate positively with compassion and negatively with fear of compassion, in accordance with our hypotheses. Examining the correlations confirmed these expectations: Emotional skills and compassion had positive but relatively low mutual correlations (.273 at T1, .34 at T2); emotional skills and fear of compassion had negative and low mutual relations (r = − .11 at T1, r = − .20 at T2, only significant at T2). Despite the low mutual correlations, we decided to examine discriminant validity by examining the separateness of emotional skills from compassion and fear of expressing compassion. To this purpose, we used confirmatory factor analysis with maximum likelihood using lavaan package in RStudio 1.0 to compare the following models: (1) a model where the items for each of the three scales loaded on separate factors, with emotional skills comprising of three subfactors, and (2) a model where the items of all three scales loaded on one common factor. In both models, the items for fear of compassion were reverse coded. The fit indices of model 1 (χ2 (df = 269) = 552.803, CFI = .831, TLI = .812, RMSEA = .083, SRMR = .089) compared favorably to model 2 (χ2 (df = 275) = 1304.806, CFI = .388, TLI = .332, RMSEA = .155, SRMR = .171), thus giving support for treating emotional skills as a separate construct as compared to compassion or the fear of expressing compassion.Footnote 1 The psychometric properties of the scale were thus deemed as satisfactory.

Main Results

Means, standard deviation, and intercorrelations between the study variables are presented in Table 2. In order to compare the progress in the treatment and control groups, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was run for each dependent variable. Before the intervention, no significant differences in any of the self-rated measures were shown between managers in the treatment and control groups.

Starting the examination with sense of emotional skills, a 2 group (treatment, control × 2 time (T1, T2) repeated-measures ANOVA yielded a significant interaction of time X group: (F(1,149) = 4.35, p = .039, η2 = .028). Follow-up within group t tests examining T2 differences between the treatment and control groups showed significant improvement for the treatment group (Table 3). Thus, the intervention was successful in increasing the sense of emotional skills supporting our first hypothesis.

For sense of compassion, a 2 group (treatment, control) × 2 time (T1, T2) repeated-measures ANOVA yielded a significant interaction of time X group: (F(1,156) = 4.89, p = .028, η2 = .030). Follow-up within group t tests examining T2 differences between the treatment and control groups showed improvement for the treatment group (Table 3), although the difference between the groups was not significant (t = 1.890, p = .061). A post hoc paired-sample t test between T1 and T2 intervention group averages (t = 2.05, p = .04) demonstrated that there was a significant improvement in the intervention group. Thus, our second hypothesis was partly supported, as compassion increased in the intervention group.

Our next hypothesis suggested that the increase in compassion in the intervention group would be mediated by emotional skills. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a mediation analysis using PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes, 2018; model 4) that uses a bootstrapping approach with 5000 bootstrap samples. In the model, compassion at T2 was the dependent variable, and condition (dummy-coded) was the independent variable, with emotional skills at T2 as the mediator. The results showed that path from condition to emotional skills was significant (b = .256, SE = .116, p = .029) and the path from emotional skills to compassion was significant (b = .392, SE = .096, p < .001) with the direct path from condition to compassion becoming insignificant (b = .228, SE = .139, p = .104). The bootstrapping for indirect effects showed that the indirect effect through emotional skills (.100, 95% CI [.012, .212]) was significant, indicating full mediation in support of our third hypothesis.

For fear of compassion, a 2 group (treatment, control) × 2 time (T1, T2) repeated-measures ANOVA yielded a significant interaction of time X group: (F(1,150) = 8.07, p = .005, η2 = .051). However, follow-up t tests examining T2 differences between the treatment and control groups showed no significant (p = .12) difference between the groups (Table 3). A post hoc paired-sample t test between T1 and T2 intervention group averages (t = 2.60, p = .01) demonstrated that there was a significant improvement in the intervention group. Thus, the results lend partial support for our fourth hypothesis.

Turning to follower-rated variables, a t test comparing baseline (T1) servant leadership ratings between treatment and control group showed a non-significant difference (t = 1.96, p = .05). A 2 group (treatment, control) × 2 time (T1, T2) repeated-measures ANOVA of servant leadership yielded a significant interaction of time X group: (F(1,155) = 6.86, p = .01, η2 = .042). Follow-up within group t tests examining T2 differences between the treatment and control groups, however, showed that the improvement was not significant (t = − .55, p = .59) for the treatment group at T2 (Table 3). However, a post hoc paired samples t test between T1 and T2 servant leadership conducted separately for treatment and control groups revealed that while there was no significant change in the control group between T1 and T2 (t = 1.19, p = .24), for the treatment group, there was a significant increase in servant leadership between T1 and T2 (t = 2.74, p = .01). Thus, our fifth hypothesis concerning the impact of the intervention on follower ratings of servant leadership was partly supported.

For autonomy support, a t test comparing baseline (T1) autonomy support ratings between treatment and control group showed no significant difference (t = − 1.02, p = .31). A 2 group (treatment, control) × 2 time (T1, T2) repeated-measures ANOVA of Autonomy Supportive Leadership yielded an insignificant interaction of time X group: (F(1,155) = 3.90, p = .05, η2 = .025). As Table 3 demonstrates, the autonomy support of the treatment group had a trend of increasing during the intervention, while the autonomy support of the control group demonstrated a decreasing trend. Follow-up within group t tests examining T2 differences between the treatment and control groups, however, showed that the improvement was not significant (t = − .08, p = .94) for the treatment group at T2 (Table 3). Thus, our sixth hypothesis was not supported.

Discussion

Our aim was to examine whether compassion could be increased in organizations among managers through a new in-depth training program that teaches compassion through improving emotional skills. In support of our hypotheses, compared to the control group, ESCT was related to significant improvement in managers’ sense of emotional skills as indicated both by a significant time X group interaction in repeated-measures ANOVA and a significant difference between the groups at time 2.

Also, managers’ sense of compassion seemed to increase, based on a significant time X group interaction, a significant increase in the intervention group between time 1 and time 2, and a difference, although not significant (p = .061), between the groups at time 2. This finding suggests that the emotional skills training could improve compassion as hypothesized. The improvement of sense of compassion was expected, because the training taught emotional skills related to strengthening of each of the four sub-process of compassion. Additionally, the training taught the three dimensions of self-compassion—mindfulness, shared humanity, and kindness—which could have contributed to an increase in compassion towards others as well, as suggested by Neff and Pommier (2012). In further support of this hypothesis that improvements of emotional skills lead to improvements in compassion, we found support for a hypothesized mediation model where the positive relationship between intervention condition and compassion was fully mediated by emotional skills.

As regards managers’ fear of compassion, it is harder to make a definitive conclusion about improvement based on this study. The time X condition interaction was significant, indicating a difference between the groups over time. Also, time 2 score of the intervention group was significantly higher than the time 1 score. However, the t test between the groups at T2 showed no significant difference (p = .12). This might be due to the effect being too subtle to be discoverable with current statistical power. Alternatively, it could be that while the training increased managers’ sense of compassion, it did not alleviate the fears they had towards compassion, perhaps because people are strongly influenced by the expectations of their social environment (Rand, Brescoll, Everett, Capraro, & Barcelo, 2016).

In partial support of our hypotheses, servant leadership showed some signs of improvement after the ESC training. The time X condition interaction was significant, and a comparison of the intervention group scores at time 1 and time 2 showed that there was a significant increase in servant leadership in the treatment group over time. However, the difference between the treatment and control groups remained insignificant at T2. It is likely that the higher baseline levels of servant leadership in the control group contributed to the time 2 difference not being significant despite a significant increase in the intervention group. The results are partly inconclusive, but they suggest that servant leadership may be improved by emotional skills training aimed to strengthen compassion. As an exploratory analysis suggested during the review process, we also tested a mediation model from intervention to servant leadership through changes in compassion, but found no support for this model as the 95% confidence intervals for indirect effects included zero [− .028, .033].

As regards autonomy support, while there was an interaction effect approaching significance, there was no significant difference at T2 between treatment and control group nor a significant improvement in the treatment group between T1 and T2. It might be that even though autonomy support begins with the manager taking the followers’ perspective in relating to their followers’ needs (Baard et al., 2004), changes in managers’ autonomy supportive behavior would need either some additional skills or a bit more time to become observable.

Overall, as most previous compassion interventions have been domain-free (Jazaieri et al., 2012; Kirby et al., 2017) or focused on meditation and employees as opposed to managers (e.g., Fredrickson et al., 2008; Scarlet et al., 2017), this study contributes to the literatures on compassion in organizations, leadership, and compassion interventions by suggesting that compassion can be increased in organizations among managers through teaching emotional skills and by introducing a new compassion-inducing emotional skills intervention and a new emotional skills measure.

Practical Implications

Organizations and employees as well as managers themselves benefit from experiencing and witnessing compassion at work (e.g., Lilius et al., 2011), while lack of compassion may result in feelings of disconnection from co-workers and decreased commitment to an organization (Lilius et al., 2008). It would thus be important for leaders and organizations to invest in building compassionate cultures by, for example, investing in compassion training, and by decreasing obstacles to compassion such as fear of appearing as weak if compassionate (Gilbert et al., 2011), or strengthening the four sub-processes of compassion process (Dutton et al., 2014). In organizations, in addition to the many positive outcomes of compassion on the sufferer and the focal actor (e.g., Dutton et al., 2007; Lilius et al., 2011), compassionate acting may give birth to feelings of elevation in observers, which, in turn, has been associated with improved commitment and increased feelings of wanting to do good and be more cooperative (Haidt, 2003). While each employee should be equipped and encouraged to do this, such behavior exemplified by managers could be particularly impactful, as employees are said to pay more attention to their managers’ behavior than vice versa (Worline & Dutton, 2017).

Limitations and Future Research

This study has limitations, which in turn point to directions for future research. First, this study reported pre- and post-findings from ESCT. Although we aimed to collect data 6 months after the intervention, unfortunately, the number of answers received at T3 was too small for analytic purposes. As behavioral changes in managers might take time to become observable, future research should carefully design longitudinal studies to help understand whether the positive impacts are sustained over time. Also, future research should study the potential factors that might facilitate or hinder the long-term effect of the training intervention. For example, factors of organizational culture, such as shared norms and perceived emotion rules related to compassion, individual personality traits related to compassion such as agreeableness, as well as exemplary behavior by leaders, and supervisory incentives that support or undermine compassion may impact whether the intervention effects will live on.

Second, while four of the seven intervention groups were randomized, three groups were quasi-randomized by the organization. This could have led to some selection bias. However, as four of the groups were randomized and the follower-rated results indicated higher baseline levels of compassion-focused servant leadership for the control instead of the treatment group, we believe the quasi-randomization was not likely to affect the results.

Third, this study did not include a placebo control group or an active comparison group in order to rule out non-specific effects like prior experience. The current study did, however, include seven different intervention groups from five different organizations, which decreases the chances of non-specific effects affecting all groups. Still, future research should carefully design randomized controlled trials and consider including a placebo or an active comparison group.

Fourth, while compassion was assessed with different compassion-related measures—compassion and fear of compassion—as well as follower-rated servant leadership and autonomy support that arguably ought to track compassionate behavior, we could not measure each of the four sub-processes of compassion separately due to the lack of existing measures for these four sub-processes. Accordingly, we call for future studies to develop separate scales for each sub-dimension of compassion and include additional methods of examining changes in compassion such as qualitative interview data. It is worth noticing that this kind of emotional skills training could potentially increase many other things as well, besides compassion, such as work engagement and work-life balance, as well as team level outcomes, such as team psychological safety and intrateam trust. However, as our focus in this paper was on compassion and constructs related to it, and on managers instead of teams, we leave testing these to future research. Also, the measure for emotional skills was developed for this study, and although the psychometric properties we tested were favorable, the scale ought to be further validated in future studies.

Fifth, the effect sizes and changes in means for the outcomes were relatively small. This was expected, as it is typical to similar kind of intervention studies (e.g., Vuorinen, Erikivi, & Uusitalo-Malmivaara, 2019), yet it still means that one has to carefully balance the time invested in such training with how big changes one can expect in the organization. Future research ought to identify the most effective modules of this and similar kinds of trainings to build briefer yet still effective compassion trainings.

Lessons learned

Researchers interested in doing compassion-based intervention studies are advised to pay attention to the following lessons learned from this study. First, to ensure adequately powered sample sizes, including follow-up data 6 or 12 months post-intervention, we advise researchers to ask participants to answer questionnaires with their real names or other fool-proof way of matching participants between surveys, to avoid unnecessary losses of answers due to misspellings or forgetting of their IDs. Also, for the same reason, we advise researchers to consider asking participants to answer questionnaires face to face as a part of the training or control condition.

Second, to conduct high-quality randomized control trial with the control condition not as a waitlist or treatment as usual, but with an active comparison such as a mindfulness-based intervention, we advise researchers to make sure that there is enough time, monetary resources, and motivation from the participant organizations to allow such careful study design.

Third, our experience was that a design with multiple meetings and enough time to allow each participant to learn emotion skills in their own rhythm was valuable in terms of not only learning, but also giving room for trust to be built among the participants of the trainings. Our recommendation is to start assessing the components of intervention designs to determine the different mechanisms of change. For example, a sense of self-efficacy (Bandura, 1982) and courage (Kanov et al., 2016) could be potential mediating factors between emotional skills and compassionate behavior. Also, such assessment could help determine whether a shorter intervention could be as effective.

Overall, in the midst of high demand for compassion at work, it is promising to see that instead of being something innate, compassion is a skill (or a set of skills) that can be increased also through training emotional skills, with observable benefits for the organization.

Notes

The fit of model 1 was not optimal, and an examination of the modification indices and residuals revealed that this is mainly due to a few fear of compassion items and compassion items having mutual modification indices. Removing two such items from fear of compassion scale and two from compassion scale improved the fit of the model towards more acceptable levels: (χ2 (df = 183) = 292.83, CFI = .91, TLI = .90, RMSEA = .06, SRMR = .07).

References

Atkins, P., & Parker, S. (2012). Understanding individual compassion in organizations: The role of appraisals and psychological flexibility. Academy of Management Review, 37, 524–546.

Baard, P. P., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2004). Intrinsic need satisfaction: A motivational basis of performance and well-being in two work settings. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34, 2045–2068.

Bakan, J. (2005). The corporation: The pathological pursuit of profit and power. London: Robinson.

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanisms in human agency. American Psychologist, 37, 122–147.

Barsade, S. G., & O’Neill, O. A. (2014). What’s love got to do with it? A longitudinal study of the culture of companionate love and employee and client outcomes in a long-term care setting. Administrative Science Quarterly, 59, 551–598.

Batson, C. D. (1994). Why act for the public good? Four answers. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20, 603–610.

Burnstein, E., Crandall, C., & Kitayama, S. (1994). Some neo-Darwinian rules for altruism: Weighing cues for inclusive fitness as a function of biological importance of the decision. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 773–807.

De Waal, F. (2009). Primates and philosophers: How morality evolved. Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press.

Deci, E. L., Connell, J. P., & Ryan, R. M. (1989). Self-determination in a work organization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 580–590.

Dutton, J. (2006). Explaining compassion organizing. Administrative Science Quarterly, 51(2006), 59–96.

Dutton, J., Workman, K., & Hardin, A. (2014). Compassion at work. The Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1, 277–304.

Dutton, J. E., Lilius, J. M., & Kanov, J. M. (2007). The transformative potential of compassion at work. In S. K. Piderit, R. E. Fry, & D. L. Cooperrider (Eds.), Handbook of transformative cooperation: New designs and dynamics, 107–26. Stanford: Stanford Univ. Press.

Ekman, P. (2007). Emotions revealed. Recognizing faces and feelings to improve communication and emotional life. Henry Holt and Company: New York.

Eldor, L. (2017). Public service sector: The compassionate workplace—The effect of compassion and stress on employee engagement, burnout, and performance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 2017, 1–18.

Fredrickson, B. L., Cohn, M., Coffey, K. A., Pek, J., & Finkel, S. A. (2008). Open hearts build lives: Positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 1045–1062.

Frost, P. J. (2003). Toxic emotions at work: How compassionate managers handle pain and conflict. Boston: Harvard Bus. School Press.

Frost, P. J., Dutton, J. E., Worline, M. C., & Wilson, A. (2000). Narratives of compassion in organizations. In S. Fineman (Ed.), Emotion in Organizations (pp. 25–45). London: Sage 2nd ed.

Gilbert, P. (2009). Introducing compassion-focused therapy. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 15, 199–208.

Gilbert, P., McEwan, K., Matos, M., & Rivis, A. (2011). Fear of compassion: Development of three self-report measures. Journal of Psychology and Psychotherapy, 84, 239–255.

Gilbert, P., & Procter, S. (2006). Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self-criticism: Overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 13, 353–379.

Goetz, J., Keltner, D., & Simon-Thomas, E. (2010). Compassion: An evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin, 136(3), 351–374.

Goleman, D., Boyatzis, R., & McKee, A. (2009). Primal leadership. Realizing the power of emotional intelligence. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Grant, A. M., Dutton, J. E., & Rosso, B. D. (2008). Giving commitment: Employee support programs and the prosocial senseaking process. Academy of Management Journal, 51, 898–918.

Greenleaf, R. K. (1977). Servant-leadership: A journey into the nature of legitimate power and greatness. New York: Paulist Press.

Guinot, J., Miralles, S., Rodriquez-Sanchez, & Chiva, R. (2020). Do compassionate firms outperform? The role of organizational learning. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 42(3), 717–734.

Haidt, J. (2003). Elevation and the positive psychology of morality. In C. L. M. Keyes & J. Haidt (Eds.), Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived (pp. 275–289). Washington, DC: American psychological Association.

Hakanen, J. J., Harju, L., Seppälä, P., Laaksonen, A., & Pahkin, K. I. (2012). Towards spirals of inspiration. Työterveyslaitos: Helsinki.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Hwang, J., Plante, T., & Lackey, K. (2008). The development of the Santa Clara brief compassion scale: An abbreviation of Sprecher and Fehr’s compassionate love scale. Pastoral Psychology, 56, 421–428.

Jazaieri, H., Jinpa, G., McGonigal, K., Rosenberg, E., Finkelstein, J., Simon-Thomas, E., & Goldin, P. (2012). Enhancing compassion: A randomized controlled trial of a compassion cultivation training program. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14, 1113–1126.

Jordan, M. R., Amir, D., & Bloom, P. (2016). Are empathy and concern psychologically distinct? Emotion, 16(8), 1107–1116.

Kanov, J., Powley, E. H., & Walshe, N. D. (2016). Is it ok to care? How compassion falters and is courageously accomplished in the midst of uncertainty. Human Relations, 70, 751–777.

Kashdan, T. B., Barrett, L. F., & McKnight, P. E. (2015). Unpacking emotion differentiation: Transforming unpleasant experience by perceiving distinctions in negativity. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24, 10–16.

Keltner, D. (2009). Born to be good: The science of a meaningful life. New York: W.W. Norton.

Kirby, J. N., Tellegen, C. L., & Steindl, S. R. (2017). A meta-analysis of compassion-based interventions: Current state of knowledge and future directions. Behavior Therapy, 48, 778–792.

Lilius, J. M., Worline, M. C., Dutton, J. E., Kanov, J. M., & Maitlis, S. (2011). Understanding compassion capability. Human Relations, 64, 873–899.

Lilius, J. M., Worline, M. C., Maitlis, S., Kanov, J. M., Dutton, J. E., & Frost, P. J. (2008). The contours and consequences of compassion at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 29, 193–218.

Lindahl, J. R., Fisher, N. E., Cooper, D. J., Rosen, R. K., & Britton, W. B. (2017). The varieties of contemplative experience: A mixed-methods study of meditation-related challenges in Western Buddhists. PLoS One, 12(5), 1–38.

Lu, X., Zhou, H., & Chen, S. (2018). Facilitate knowledge sharing by leading ethically: The role of organizational concern and impression management climate. Journal of Business and Psychology, 2019(34), 1–20.

Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., & Caruso, D. (2000). Models of emotional intelligence. In R. Stenberg (Ed.), Handbook of intelligence (pp. 396–420). Cambridge: Cambridge Univ.Press.

McLaughlin, E., Huges, G., Fergusson, R., & Westmarland, L. (2003). Restorative justice: Critical issues. London: Sage.

Melwani, S., Mueller, J. S., & Overbeck, J. R. (2012). Looking down: The influence of contempt and compassion on emergent leadership categorizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97, 1171–1185.

Neff, K., & Germer, C. (2013). A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69, 28–44.

Neff, K. D., & Pommier, E. (2012). The relationship between self-compassion and other-focused concern among college undergraduates, community adults, and practicing meditators. Self and Identity, 2012, 1–17.

Nübold, A., Van Quaquebeke, N., & Hülsheger, U. (2019). Be(com)ing real: A multi-source and an intervention study on mindfulness and authentic leadership. Journal of Business and Psychology, 2019, 1–20.

O’Donohoe, S., & Turley, D. (2006). Compassion at the counter: Service providers and bereaved consumers. Human Relations, 59(10), 1429–1448.

Otis, N., & Pelletier, L. G. (2005). A motivational model of daily hassles, physical symptoms, and future work intentions among police officers. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 35, 2193–2214.

Patterson, K. A. (2003). Servant leadership: A theoretical model. Virginia Beach, VA:Regent University (ATT No. 3082719).

Rand, D. G., Brescoll, V. L., Everett, J. A. C., Capraro, V., & Barcelo, H. (2016). Social heuristics and social roles: Intuition favors altruism for women but not for men. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 145, 389–396.

Reis, H. R., & Aron, A. (2008). Love: What is it, why does it matter, and how does it operate? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 80–86.

Reis, H. T., Sheldon, K. M., Gable, S. L., Roscoe, J., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). Daily well-being: The role of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 419–435.

Rodriguez-Carvajal, R., De Rivas, S., Herrero, M., Moreno-Jimenez, B., & Van Dierendonck, D. (2014). Leading people positively: Cross-cultural validation of the servant leadership survey. Spanish Journal of Psychology, 17(2), 1–13.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68–78.

Satterfield, J. M., & Hughes, E. (2007). Emotion skills training for medical students: A systematic review. Medical Education, 41, 935–941.

Scarlet, J., Altmeyer, N., Knier, S., & Harpin, E. (2017). The effects of compassion cultivation training (CCT) on health-care workers. Clinical Psychologist, 21, 116–124.

Singer, T., & Klimecki, O. (2014). Empathy and compassion. Current Biology, 24(18), 875–878.

Sprecher, S., & Fehr, B. (2005). Compassionate love for close others and humanity. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 22, 629–651.

Tsui, A. (2013). On compassion in scholarship: Why should we care? Academy of Management Review, 38, 167–180.

Van Dierendonck, D. (2011). Servant leadership: A review and synthesis. Journal of Management, 37, 1228–1261.

Van Dierendonck, D., & Nuijten, I. (2011). The servant leadership survey: Development and validation of a multidimensional measure. Journal of Business and Psychology, 26, 249–267.

Van Dierendonck, D., & Patterson, K. (2014). Compassionate love as a cornerstone of servant leadership: An integration of previous theorizing and research. Journal of Business Ethics, 128, 119–131.

Van Kleef, G., Oveis, C., Can der Löwe, I., LuoKogan, A., Goetz, J., & Keltner, D. (2008). Power, distress, and compassion. Psychological Science, 19, 1315–1322.

Vuorinen, K., Erikivi, A., & Uusitalo-Malmivaara, L. (2019). A character strength intervention in 11 inclusive Finnish classrooms to promote social participation of students with special educational needs. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 19(1), 45–57.

Weick, K. E. (2012). Organized sensemaking: A commentary on processes of interpretive work. Human Relations, 65, 141–153.

Weick, K. E., Sutcliffe, K. M., & Obstfeld, D. (2005). Organizing and the process of sensemaking. Organization Science, 16, 409–421.

Williams, G. C., & Deci, E. L. (1996). Internalization of biopsychosocial values by medical students: A test of self-determination theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 767–779.

Williams, G. C., Grow, V. M., Freedman, Z., Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (1996). Motivational predictors of weight loss and weight-loss maintenance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 115–126.

Worline, M., & Dutton, J. E. (2017). Awakening compassion at work: The quiet power that elevates people and organizations. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Zineldin, M., & Hytter, A. (2012). Leaders’ negative emotions and leadership styles influencing subordinates’ well-being. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(4), 748–758.

Acknowledgments

Open access funding provided by University of Helsinki including Helsinki University Central Hospital. The authors gratefully acknowledge Business Finland (Tekes, The Finnish Funding Agency for Innovation), and University of Helsinki for funding of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix. All Items of the Sense of Emotional Skills Measure

Appendix. All Items of the Sense of Emotional Skills Measure

1. I understand what emotions are.

2. I find that emotions are important in the working life.

3. I find that I can affect my own emotions.

4. I find that I can influence my colleagues’ emotions.

5. I feel that I can, for my part, influence the working atmosphere of our work place.

6. I feel that I have the means and the ability to face and handle negative emotions at the work place.

7. I feel that I express interest towards my subordinates.

8. I feel that I express respect towards my subordinates.

9. I feel that I strengthen my subordinates’ feeling of managing their work.

10. I highlight/make visible my subordinates’ progress in their work.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Paakkanen, M., Martela, F., Hakanen, J. et al. Awakening Compassion in Managers—a New Emotional Skills Intervention to Improve Managerial Compassion. J Bus Psychol 36, 1095–1108 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-020-09723-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-020-09723-2