Abstract

This study investigates individual and organizational factors that motivate employees to enact the work role in the nonwork domain (work-to-nonwork integration behavior). We argue that implications of work-to-nonwork integration may be better understood by learning more about the reasons why employees perform integration behavior. Based on the reasoned action approach (RAA), we examined four antecedents of employee integration behavior: individuals’ attitudes toward integration (integration preference), perceived employer expectations (injunctive norms), perceived integration behavior of coworkers (descriptive norms), and perceived control to manage the work–nonwork interface (behavioral control). The results of structural equation modeling with a heterogeneous sample of 748 employees indicated the relevance of all four RAA factors in explaining integration behavior 1 month later. Specifically, the individual preference to integrate evolved as the strongest motivational aspect, followed by injunctive norms. Additionally, our results suggest that injunctive and descriptive norms each explained unique variance in integration behavior. Organizational interventions may aim at shaping both norms and behavioral control to improve employees’ work–nonwork boundary management. Furthermore, making employees aware of the importance of their integration preferences is a critical factor for actively managing the work–nonwork interface.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Innovations and societal changes are well-known factors impacting the way we work. In this regard, recent technological innovations, the rise of dual-income families, and globalization, among others, have contributed to an increased integration of work aspects into the nonwork domain (Rothbard & Ollier-Malaterre, 2016). This study focuses on work-to-nonwork integration behavior (integration behavior), which we define as the enactment of behaviors relevant to the work role in the nonwork domain, thereby integrating work and nonwork roles (e.g., working at home, during vacations, and/or when spending time with friends and family). This definition draws upon the permeability of role boundaries, namely, the extent to which an individual is involved in the work role, while being physically located in another role’s domain (Ashforth, Kreiner, & Fugate, 2000).

A growing research body has dealt with potential implications of increased work-to-nonwork integration for employee health and well-being, yet findings remain inconclusive (Allen, Cho, & Meier, 2014; Rothbard & Ollier-Malaterre, 2016): While work-to-nonwork integration allows for positive spillover and enrichment (e.g., Powell & Greenhaus, 2010), work-to-nonwork integration also facilitates negative spillover and conflict (e.g., Hecht & Allen, 2009; Kossek, Ruderman, Braddy, & Hannum, 2012; Powell & Greenhaus, 2010; Wepfer, Allen, Brauchli, Jenny, & Bauer, 2018).

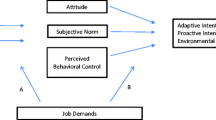

We argue that research concerning the impact of work-to-nonwork integration behavior on employee health and well-being may be better understood when we learn more about the reasons that initially lead to work-to-nonwork integration. For example, it seems plausible that the impact of work-to-nonwork integration may differ if employees perform work-to-nonwork integration behavior due to personal interest or organizational pressure. Thus, we regard it essential to shed light on the initial employee motivation to perform integration behavior. This study seeks to examine individual and organizational factors that motivate employees to integrate work into the nonwork domain. For this purpose, we draw on the reasoned action approach (RAA; Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010), which focuses on the initial motivation phase of a behavior (Schwarzer, 2014). According to the RAA, human behavior is a function of attitude toward the behavior, perceived norms, and perceived behavioral control. Drawing on this conceptual framework, we suggest that (a) individual integration preference, (b) integration norms of the employees’ organizations (perceived employer expectations and coworkers’ integration behavior), and (c) perceived behavioral control are main antecedents of employee integration behavior.

This study makes a unique contribution to the work–nonwork literature by applying a well-established theoretical framework to work–nonwork research in order to break down the complexity in understanding the factors that motivate employees’ work-to-nonwork integration behavior. To this end, we examine the degree to which antecedents defined by the RAA jointly contribute to performing work-to-nonwork integration behavior. While various antecedents have been investigated by existing work–nonwork integration research hitherto, our study brings together constructs that are often studied in isolation or piecemeal combination. Through this theory-guided approach to the combined study of significant antecedents, we also propose the RAA as a framework to organize existing findings. Furthermore, by making use of the RAA as a well-established theoretical framework, we answer the call for increased application of theory in work–nonwork research (Matthews, Wayne, & McKersie, 2016). Furthermore, this study meets demands to empirically interrelate individual (integration preference) and organizational antecedents (integration norms) of integration behavior (e.g., Kossek & Lautsch, 2012; Kreiner, 2006). Finally, we also contribute to research on organizational norms and social pressure in the context of integration behavior by distinguishing between two forms of perceived norms, namely injunctive norms (perceptions of what one should do) and descriptive norms (perceptions of what others actually do; Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010).

Work-to-Nonwork Integration Behavior

According to the boundary theory (Ashforth et al., 2000; Nippert-Eng, 1996), individuals create and maintain idiosyncratically constructed lines of demarcation around specific domains of their lives, so-called boundaries, to simplify and order their environment. These boundaries may be understood as “mental fences” (Zerubavel, 1991, p. 16) that an individual perceives as real and acts upon. Two typical examples of domains that arise by creating boundaries around them are the work domain and the nonwork domain. The work domain includes employees’ professional lives, particularly characterized by pursuing a profession in return for wage. The nonwork domain comprises employees’ private lives, including their families, hobbies, volunteer work, etc. While these domains are characterized by a general consensus about what they are (e.g., domains like “work” and “home” are defined similarly by many individuals), there are individual variations in the definition and the separation of these domains (Ashforth et al., 2000; Nippert-Eng, 1996). Opportunities to idiosyncratically construct these domains are abundant in contemporary work, where boundaries between work and nonwork domains are becoming much more permeable and flexible (Ashforth et al., 2000). As a result, they allow for work or nonwork activities to be integrated in the other domain, which encompasses enacting a certain role in another role domain (e.g., bringing work home). The extent of such cross-domain integration can be understood as a continuum, where complete segmentation of domains marks one end and complete integration the other end (Ashforth et al., 2000; Nippert-Eng, 1996). Previous research has shown that an individual’s work–nonwork integration activities are often asymmetrical (Hecht & Allen, 2009; Kossek et al., 2012). Thus, scholars have proposed to discriminate between the directions of integration to clarify the specific processes between work and nonwork domains (e.g., Kossek & Lautsch, 2012). Because investigating the work-to-nonwork direction allows to identify aspects of the work environment that are vital to designing health-promoting working conditions, this study focuses on work-to-nonwork integration behavior.

The RAA as a Framework for Understanding Integration Behavior

Previous research has examined a number of contextual antecedents of integration behavior, among which are individual preferences (Matthews, Barnes-Farrell, & Bulger, 2010; Methot & LePine, 2016; Powell & Greenhaus, 2010; Richardson & Benbunan-Fich, 2011), social norms and expectations (Park, Fritz, & Jex, 2011; Piszczek, 2016), and the perceived scope of action concerning integration possibilities and abilities (Clark, 2002; Matthews et al., 2010). Until now, however, little attempt has been made to investigate these potential antecedents within a theory-based framework (e.g., Kossek & Lautsch, 2012). We regard the RAA by Fishbein and Ajzen (2010) as a suitable theoretical framework to integrate previously identified antecedents and relate them to integration behavior. The RAA is applied as a powerful predictive model of behavior in many fields (e.g., McEachan et al., 2016) and has also received consideration in the field of vocational behavior (e.g., Kim, Hornung, & Rousseau, 2011; Sheeran & Silverman, 2003). Recently, the RAA has been reviewed as a theoretical framework to expand work–family research (Matthews et al., 2016).

The RAA is the latest expansion of Fishbein and Ajzen’s theoretical work to predict and change human behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010; for an overview of theory development, see Head & Noar, 2014). Fishbein and Ajzen (2010) assume that the prediction of human behavior is not as complex as commonly perceived as it can be broken down into a limited set of constructs. According to the RAA, human behavior can be predicted from a person’s intentions to engage in a certain behavior, and these intentions are determined by (a) the person’s attitude toward the behavior, (b) perceived norms in terms of social pressure and social desirability regarding the behavior, and (c) perceived control over the behavior in question. Corresponding behavioral, normative, and control beliefs underlie these three proposed antecedents.

In this study, we draw on the RAA to investigate the influence of employees’ perceptions on integration behavior regarding (a) their individual attitude toward integration behavior (integration preference), (b) the extent to which others expect them to integrate (injunctive norms) and the extent to which their direct work environment shows integration behavior (descriptive norms), and (c) last but not least their amount of skills and abilities to perform integration behavior (behavioral control).

Although our research approach is based on the RAA, we have undertaken two theoretical simplifications for this study that are common in the context of the RAA (Head & Noar, 2014). The first adaption concerns the measurement of behavioral, normative, and control beliefs, which, from a theoretical perspective, are assumed to determine attitudes, norms, and behavioral control, respectively. However, the added value of beliefs to the RAA model is considered to be overrated, both from a content-related perspective (conceptual similarity and overlap with attitudes, norms, and control) and from a methodological perspective (negligible increase of explained variance; Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). In congruence with the majority of research that applies the RAA, we will directly measure attitudes, norms, and behavioral control as antecedents of integration behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). The second adaption concerns the “intention-behavior gap,” which refers to the phenomenon that in contrast to the clear prediction of the RAA, individuals often do not engage in their intended behavior (Head & Noar, 2014; Sheeran, 2002). Because this shortcoming of the RAA questions the utility of measuring intentions in seeking to predict behavior (Schwarzer, 2014), we chose to disregard intentions and instead look at the direct links between antecedents and actual (integration) behavior.

In conclusion, we chose the RAA as theoretical framework for this study for two reasons: Firstly, the RAA is established in work and organizational psychology research and Fishbein and Ajzen (2010) report positive experience concerning the application in this field. Secondly, the research field of work–nonwork boundary dynamics is complex with various agents (e.g., members, demands, and needs of both the work and nonwork domain) and directions (e.g., within and between domains; Allen et al., 2014; Ashforth et al., 2000). Because the RAA has the potential to break down the complexity of human behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010), we consider it to be a good theoretical framework for work–nonwork research, specifically to predict, explain, and understand integration behavior. The next section of this paper will introduce the behavioral antecedents of the RAA and illustrate the respective links to integration behavior (see also Fig. 1).

Antecedents of Work-to-Nonwork Integration Behavior

Individual Attitude Toward Integration Behavior: Integration Preference

An attitude, quite generally, may be defined as a “latent disposition or tendency to respond with some degree of favorableness or unfavorableness to a psychological object” (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010, p. 125) and is thus bipolar evaluative in nature. In the RAA context, the psychological object is the behavior of interest and the evaluation concerns the attitude toward personally performing this behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). Two types of attitudes can be distinguished: experiential and instrumental (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). While experiential attitudes are concerned with positive or negative emotional experiences associated with performing the behavior, the concept of instrumental attitudes focuses on positive or negative consequences of the behavior. It is strongly influenced by the expectancy-value model (see Feather, 1982), which posits that individuals are likely to engage in behavior they anticipate leading to a desired and personally valued result (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). In regard to integration behavior, interindividual differences in the attitude toward integration behavior and the corresponding anticipated results have shown to be of prime importance (Kreiner, 2006; Nippert-Eng, 1996). In keeping with both aspects of attitudes, it thus stands to reason that individuals act according to both emotional experiences associated with performing a certain integration behavior and cognitive evaluations concerning its consequences.

In accordance with Kossek and Lautsch (2012), determinants and constraints from both the work (e.g., work setting) and the nonwork domain (e.g., family) are partially captured in the individual’s attitude toward integration behavior. For example, study results by Matthews et al. (2010) suggest that an individual’s work and nonwork centrality (i.e., individual’s attribution of meaningfulness to each domain) are reflected in the individual’s attitude toward integration behavior. Likewise, family involvement, marital status, and the number of children aged 18 or under in the same household show positive significant relations with the preference to segment work from the family domain (Powell & Greenhaus, 2010). In sum, a person’s attitude toward integration behavior has evolved through various work and nonwork influences, and this attitude expresses a person’s preference to integrate work into the nonwork domain (integration preference). Individuals with a high integration preference prefer to merge or blend work aspects into their nonwork lives, while individuals with a low integration preference prefer to keep work aspects out of their nonwork lives, and thus prefer to segment their work lives from their nonwork lives. Integration preference is usually measured as a global favorability attitude, which omits the differentiation between experiential and instrumental attitudes. However, according to Fishbein and Ajzen (2010), a valid measure of attitude need not necessarily capture both instrumental and experiential aspects of attitude.

In their cross-level model of work–family boundary management styles in organizations, Kossek and Lautsch (2012) proposed a direct relationship between an individual’s preference and their integration behavior. Empirical evidence confirms the proposition such that individuals who prefer to segment (integrate) work and nonwork domains report less (more) work aspects being integrated into the nonwork domains (e.g., Matthews et al., 2010; Methot & LePine, 2016; Powell & Greenhaus, 2010). Segmentation/integration preferences also show significant relations to work-related technology use in nonwork time (Park et al., 2011; Piszczek, 2016; Richardson & Benbunan-Fich, 2011). Of course, various work and nonwork factors may prevent employees from fully aligning their integration behavior with their integration preferences (Methot & LePine, 2016). Nevertheless, in line with previous research (e.g., Methot & LePine, 2016), we expect that employees will adjust their integration behavior to reflect their integration preference to the best possible degree.

Hypothesis 1: Integration preference is positively related to work-to-nonwork integration behavior.

Perceived Integration Norms: Injunctive and Descriptive Norms

In the RAA context, norms are understood as “perceived social pressure to perform (or not to perform) a given behavior” (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010, p. 130) and constitute another significant antecedent in the prediction of behavior. Work–nonwork research has also recognized the potential influence of norms on employee integration behavior through organizational context and climate (e.g., Fenner & Renn, 2004; Kossek & Lautsch, 2012).

The RAA includes the notion of perceived norms consisting of two different aspects of social pressure (Cialdini, Reno, & Kallgren, 1990; Deutsch & Gerard, 1955). The first and originally single aspect, injunctive norms, refers to the perceptions of what important referent individuals or groups think “should or ought to be done with respect to performing a given behavior” (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010, p. 131). Injunctive norms often affect behavioral rules that apply equally to all members of a specific group (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). The second aspect added later, descriptive norms, is based on the assumption that peer pressure is an important determinant for behavior and thus refers to perceptions that important others “are or are not performing the behavior in question” (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010, p. 131). The distinction of injunctive and descriptive norms has been supported both theoretically (e.g., Kok & Ruiter, 2014) and empirically (e.g., Manning, 2009).

Referring to Deutsch and Gerard (1955), Manning (2009) points out that injunctive and descriptive norms may refer to different sources of motivation. Injunctive norms, on the one hand, may be triggered by the motivation to comply or to avoid social sanctions (Ajzen, 1991; Lapinski & Rimal, 2005). Injunctive norms may thus be viewed as organizational performance expectations whose compliance will be rewarded (Fenner & Renn, 2004; Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). Descriptive norms, on the other hand, may be valued as behavioral cues concerning appropriate and effective behavior in a specific situation, in terms of “if everyone is doing it, it must be a sensible thing to do” (Cialdini et al., 1990, p. 1015). Parallels may be drawn to social learning theory (Bandura, 1977), according to which employees rely on role models (e.g., supervisors, colleagues) and imitate their behavior when positive consequences are expected.

Both injunctive and descriptive norms have been studied in the context of technology-assisted integration behavior, albeit rarely together within a single study. Barber and Santuzzi (2015) found prescriptive (injunctive) but not descriptive norms to be associated with technology-related boundary crossing behaviors. Derks, van Duin, Tims, and Bakker (2015) found both normative (injunctive) supervisor expectations and peer (colleague) influence regarding smartphone use during after-work hours to be positively associated with daily smartphone use after work hours. While their measure of peer influence comprised both normative pressure (injunctive norms) and behavioral aspects (descriptive norms), they investigated neither injunctive nor descriptive peer norms separately. Concerning injunctive norms studied in isolation, a study by Piszczek (2016) found a significant positive relation between organizational expectations to be available through mobile technologies in nonwork time (injunctive norms) and the extent of employee technology-assisted integration behavior. Two qualitative studies support this positive relation (Duxbury, Higgins, Smart, & Stevenson, 2014; Mazmanian, Orlikowski, & Yates, 2013). Concerning descriptive norms studied in isolation, research by Richardson and Benbunan-Fich (2011), for example, has identified descriptive norms as one of several antecedents of work connectivity behavior after hours. In addition, the results of Park et al. (2011) show that perceived segmentation behavior of an employee’s close work environment is related to less work-related technology use at home. The qualitative results of Mazmanian et al. (2013) illustrate how descriptive norms regarding technology-assisted integration behavior develop organically in an organization as they are shared among employees, and how these norms are self-reinforcing over time, as work-related technology use of colleagues and supervisors in their nonwork domains increases. Finally, there is reason to believe that integration behavior in general may signal effectiveness, competency (Mazmanian et al., 2013), and career commitment (Roberts, 2007), and may thus be critical for career success. Analyses of Song (2009) point toward this signal effect of integration behavior as the results indicate that unpaid overtime work at home is both motivated by and associated with future wage increases and promotions.

While these studies focused primarily on technology-assisted integration behavior, we propose the findings also apply to a broader definition of integration behavior used in this study. In congruence with the RAA framework (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010), we thus assume that perceived integration norms, and specifically injunctive norms (i.e., employer expectations regarding integration behavior) and descriptive norms (i.e., integration behavior of coworkers), are antecedents of integration behavior.

Hypothesis 2: Injunctive norms are positively related to work-to-nonwork integration behavior.

Hypothesis 3: Descriptive norms are positively related to work-to-nonwork integration behavior.

Behavioral Control

Behavioral control is valued as a further relevant antecedent in the RAA framework, as a lack of control to perform a certain behavior may impede its successful performance. The notion of control includes both internal (e.g., skills and abilities) and external (e.g., working conditions) elements (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). However, the factors that determine actual control over a certain behavior are often unclear, and so is relevant information about these factors. Instead, perceived behavioral control is acknowledged as a proxy for actual control, considered to reflect the latter accurately to an acceptable extent (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). Perceived behavioral control reflects “the extent to which people believe that they are capable of, or have control over, performing a given behavior” (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010, p. 64), which points to two distinct aspects: capacity (i.e., the belief that one is capable to perform the behavior) and autonomy (i.e., the degree of control over performing the behavior). According to Fishbein and Ajzen (2010), capacity and autonomy represent two aspects of both perceived behavioral control and self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977). Thus, by definition, perceived behavioral control and self-efficacy are two conceptually very close constructs.

In the work–nonwork context, a further finding of two previously mentioned qualitative studies suggests that employer-provided mobile technologies are perceived as a factor enabling and actively promoting integration behavior (Duxbury et al., 2014; Mazmanian et al., 2013). While some regard these technologies as a tool to successfully manage the work–nonwork interface, others perceive them as a tool that deprives them of control in their work–nonwork boundary management.

According to Kossek et al. (2012), it is not the ease or the amount of work–nonwork boundary transitions that determine the success of individual work–nonwork boundary management but the extent of perceived control over these work–nonwork integration processes. Individuals in jobs with low control over where, when, and how they work (e.g., assembly line employees, on-site customer service employees) will not have the same opportunities to decide on their integration behavior as employees with high flexibility in determining when and where they work (Kossek & Lautsch, 2012). Preliminary correlative evidence by Clark (2002) supports this line of research and implies that perceived flexibility around work is positively related to work-to-nonwork integration. In contrast, research by Matthews et al. (2010) could not establish a significant link between work flexibility-ability and integration behavior.

Based on the RAA and work–nonwork research, we thus define behavioral control as the degree to which individuals perceive that they are capable of, or have control over, performing integration behavior. Because empirical evidence concerning behavioral control and integration behavior is ambiguous, we assume that behavioral control is related to integration behavior, with both directions being possible.

Hypothesis 4: Behavioral control is related to work-to-nonwork integration behavior.

Method

Procedure and Participants

The study was conducted in winter 2016 in Austria and Germany with the support of students generating data for their bachelor’s theses in psychology. On the condition that participants of the study had to be employed at least part-time (15 h per week), we were able to secure a heterogeneous sample including a wide range of ages, occupations, and job levels. This sampling approach (1) helps to overcome a previously stated work–nonwork research limitation of overly homogeneous samples of one organization or occupation (e.g., Parasuraman & Greenhaus, 2002) and (2) secures the essential sample variance to assess the question raised in this study. To help reduce common method variance (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, & Podsakoff, 2012), the survey was conducted in two waves 1 month apart with integration behavior being assessed in wave 2 (M = 30.05 days; SD = 4.68 days).

Data for both points of measurement were collected online, yet paper/pencil questionnaires were provided on demand. Respondents’ participation was voluntary and anonymity was guaranteed. Wave 1 yielded 985 respondents, 748 of which participated in wave 2 and could be matched to their wave 1 participation. The paper–pencil option was chosen by 36 participants. We checked the data for data entry mistakes and careless responding, employing a technique similar to the “LongString” response pattern method in Meade and Craig (2012). An analysis of missing values revealed that among all variables included in the study, two showed 9 missing values (1.2%), which was the highest number of missing values. Little’s MCAR test yielded a statistically nonsignificant result, χ2(455) = 486.56, p = 0.15, which suggests a “missing completely at random” (MCAR) pattern of missing values. Wave 2 had a stronger contribution of women, 58.3 vs. 50.5%, χ2(1) = 4.16, p = 0.04, and participants had fewer children under the age of 18 living in the same household, MW2 = 0.27, MW1 = 0.41, t(291) = − 2.34, p = 0.02, but were otherwise similar to those who participated only in wave 1. The final sample was 58% female with an average age of 37.86 years (range 18–67, SD = 13.05), 75% of participants had a partner, and 18% had children under the age of 18 living in the same household. The average working hours were 34.44 h per week (range 15–60, SD = 8.19) and 26% of the participants held a leadership position. Participants in the teaching profession (primary school, secondary school, university) constituted the biggest homogeneous subgroup (14%) in the wide range of represented professions.

Measures

Integration preference was measured with three items of the segmentation preference scale developed by Kreiner (2006; e.g., “I prefer to keep work life at work”; “I don’t like work issues creeping into my home life”; Cronbach’s alpha [α] = 0.90). Since we were unaware of a measure that differentiates between instrumental and experiential attitudes in the context of boundary management, we resorted to an instrument that captures a global favorability attitude. Furthermore, in order to maintain a stronger behavioral focus, we omitted one item from the original scale that referred to cognitions about work at home. Items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). We reverse-coded the items so that higher values indicated a stronger individual preference for integrating work into the nonwork domain.

Injunctive norms were measured with four items of the temporal flexibility requirements scale developed by Höge (2011). In accordance with the RAA, the injunctive norms measure directly refers to the perceived expectations of an important other, here the employer (e.g., “In my work, my employer expects from me to be flexible as far as my working hours are concerned”; “In my work, my employer expects from me to work in the evenings, at night and at weekends”; α = 0.75). We omitted one item because it referred to family life affecting work, which was not a focus of this study. Participants rated each item on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree).

Descriptive norms were measured with three items of the modified segmentation supplies scale developed by Kreiner (2006). In accordance with the approach of Park et al. (2011), the scale was modified to capture the behavior of people at the respondents’ workplace rather than describing the workplace itself (e.g., “The people I work with can keep work matters at work”; “The people I work with are able to prevent work issues from creeping into their home life”; α = 0.94). Focusing on coworkers’ integration behavior also aligns with the RAA requirements to measure descriptive norms (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). In accordance with our measure for integration preference, we omitted one cognition-related item so that wordings of the remaining items corresponded to the integration preference items. Participants rated each item on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). We subsequently reverse-coded the items so that higher values indicated stronger perceptions of the descriptive workplace norms favoring the integration of work into the nonwork domain.

Behavioral control was measured with three items of the boundary control scale by Kossek et al. (2012; e.g., “I control whether I combine my work and personal life activities throughout the day”; “I control whether I am able to keep my work and personal life separate”; α = 0.76). We were not aware of a measure that assesses the internal capacity aspect of boundary control and therefore focused on the aspect of external autonomy. Respondents rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

The dependent variable, work-to-nonwork integration behavior, was measured in wave 2 with five items of the work interrupting nonwork behaviors scale developed by Kossek et al. (2012). While several scales have been developed with different labels to measure integration behavior (a phenomenon referred to as “jangle fallacy” by Allen et al., 2014), we chose this measure because the items capture the actual performance of work-to-nonwork integration behavior (e.g., “I regularly bring work home”; “I work during my vacations”; α = 0.89) rather than difficulties arising from it (such as interruptions or conflict, which are referred to as “dysfunctional permeations” by Allen et al., 2014). Participants answered on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

According to the RAA, individual background factors can influence both formation of the antecedents and subsequent behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). Following recommendations by Becker et al. (2016), we carefully selected conceptually meaningful covariates and give justifications for each. Seven covariates pertaining to gender, life stage, family, and work structure were included (i.e., age, gender, relationship status, number of children under the age of 18 in household, weekly working hours, leadership position, teaching profession). Because research suggests that men and women differ in preference for and enactment of integration strategies in the course of various life stages (Duxbury et al., 2014; Nippert-Eng, 1996; Powell & Greenhaus, 2010), gender (1 = female; 2 = male) and age (continuous) were controlled. Because the individual’s family structure is assumed to influence the work–nonwork interface (Ashforth et al., 2000; Friedman & Greenhaus, 2000; Nippert-Eng, 1996; Powell & Greenhaus, 2010), relationship status (0 = not in relationship; 1 = in relationship) and number of children under the age of 18 living in the same household (continuous) were controlled. Because the work–nonwork time ratio is likely associated with an individual’s integration strategies (Nippert-Eng, 1996), we controlled for average weekly working hours (continuous). Because a higher hierarchical position is likely to lead to greater work demands and greater flexibility that could both influence an individual’s experience of the work–nonwork interface (Nippert-Eng, 1996; Powell & Greenhaus, 2010), leadership position (0 = no; 1 = yes) was controlled. Finally, because work–nonwork experiences may vary by occupation and work organization (Kossek & Lautsch, 2012; Nippert-Eng, 1996), and teachers make up the largest homogenous group in the explicitly heterogeneous sample, we controlled for teaching profession (0 = no; 1 = yes).

Data Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to establish the measurement model of latent variables. Hypothesized effects of antecedents of integration behavior (Hypotheses 1–4) were tested through structural equation modeling (SEM) with full maximum likelihood estimation. All analyses were conducted using AMOS 23. Model fit was evaluated using an established set of goodness-of-fit indices and conventional rules of thumb for their cutoffs (e.g., Hu & Bentler, 1999). Besides the chi-square value (χ2), we used the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) which should be 0.90 or higher. Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) values below 0.08 signify satisfactory and below 0.05 good fit. Together with the RMSEA, we report its 90% confidence interval (CIRMSEA) and a p value for the test of the null hypothesis that the RMSEA for the model in the overall population does not exceed 0.05.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

CFA were conducted to ensure that the measures were distinct latent constructs. The measurement model was tested by allocating the respective 18 items to five latent factors (integration preference, injunctive norms, descriptive norms, behavioral control, integration behavior). The 5-factor model fit the data well, χ2(125) = 456.00, p < 0.01; χ2/df = 3.65; CFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.94; RMSEA = 0.06; CIRMSEA = [0.05; 0.07], p < 0.01. Since injunctive and descriptive norms are occasionally consolidated into a single norms factor (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010), we computed an alternative 4-factor measurement model with a single integration norms factor (indicators of both injunctive and descriptive norms loading on this factor). Fit indices for this alternative 4-factor measurement model were unacceptable, χ2(129) = 1164.19, p < 0.01; χ2/df = 9.03; CFI = 0.87; TLI = 0.83; RMSEA = 0.10; CIRMSEA = [0.10; 0.11], p < 0.01, and, accordingly, inferior to the 5-factor measurement model. Descriptive statistics, intercorrelations, and internal consistencies of all study variables are shown in Table 1. The four antecedent variables were all significantly correlated with the dependent variable integration behavior (all p < 0.01) in expected directions. In addition, descriptive norms were positively correlated with both integration preference (r = 0.35, p < 0.01) and injunctive norms (r = 0.10, p < 0.01), and behavioral control was negatively correlated with injunctive norms (r = − 0.12, p < 0.01).

Antecedents of Integration Behavior

Based on the measurement model, the hypothesized structural model was specified. Age, gender, relationship status, number of children under 18 years in household, working hours, leadership position, and teaching profession were included as covariates. The model showed good fit, χ2(217) = 684.59, p < 0.01; χ2/df = 3.15; CFI = 0.95; TLI = 0.92; RMSEA = 0.05; CIRMSEA = [0.05; 0.06], p = 0.09. Standardized estimates for this model and intercorrelations of the main study variables appear in Fig. 2.

According to the structural model, and in support of Hypothesis 1, integration preference was positively related to integration behavior 1 month later (β = 0.27, p < 0.01). Both injunctive norms (β = 0.24, p < 0.01) and descriptive norms (β = 0.12, p < 0.01) related positively to integration behavior and thus supported Hypothesis 2 and Hypothesis 3, respectively. Finally, behavioral control was negatively associated with integration behavior 1 month later (β = − 0.14, p < 0.01) supporting Hypothesis 4.

The significant effects and correlations of covariates in the structural model, not shown in Fig. 2 to keep the figure simple, were as follows: Teaching profession was positively related to integration behavior (β = 0.44, p < 0.01), and the positive association between leadership position and integration behavior approached statistical significance (β = 0.06, p = 0.05). Participants’ age (r = 0.14, p < 0.01), leadership position (r = 0.10, p < 0.05), and teaching profession (r = 0.33, p < 0.01) were positively related to integration preference, whereas weekly working hours (r = − 0.16, p < 0.01) were negatively related to integration preference. The number of children under 18 years in the household was negatively related to injunctive norms (r = − 0.10, p < 0.05), whereas weekly working hours (r = 0.14, p < 0.01) and leadership position (r = 0.14, p < 0.01) were positively related to injunctive norms. Being male rather than female (r = − 0.12, p < 0.01) and weekly working hours (r = − 0.12, p < 0.01) were negatively related to descriptive norms, whereas teaching profession was positively related to descriptive norms (r = 0.29, p < 0.01). Age (r = 0.08, p < 0.05) and being male rather than female (r = 0.09, p < 0.05) were positively related to behavioral control, whereas teaching profession was negatively related to behavioral control (r = − 0.08, p < 0.05).

Additional Analyses

In order to assess whether the effect magnitudes of injunctive norms and descriptive norms could be assumed to differ in the population, we computed a χ2 difference test for the hypothesized structural model and an alternative model with equality constraints placed on the loadings of both norms factors. The result showed a significantly better fit for the model without equality constraints, Δχ2(1) = 6.93, p < 0.01, which suggests a higher effect magnitude of injunctive norms compared to descriptive norms.

While we controlled our analyses for weekly working hours due to inclusion of part-time workers employed as little as 15 h per week, this strategy could not account for possible qualitative differences between part-time and full-time workers regarding the extent, need, and ability for work–nonwork integration. Since 30.1% of our participants reported working no more than 30 h per week, we conducted an additional moderator analysis in order to assess whether the main effects of the investigated antecedents of integration behavior depended upon the degree of employment. In doing so, we tested three different models using 20, 30, and 35 h per week as cutoff values. We found no evidence for a moderating effect of degree of employment in any model, ∆χ2(4) = 3.30, p = 0.51 (20 h), ∆χ2(4) = 1.96, p = 0.74 (30 h), ∆χ2(4) = 3.29, p = 0.51 (35 h). This suggests that our results are not affected by the rather large variation in participants’ weekly working hours.

To investigate the possible impact of covariates on the relationships between independent variables (antecedents) and the dependent variable (integration behavior), we tested two additional models and compared them to the proposed model. According to Becker et al. (2016), if the standardized coefficients of predictors differ by less than 0.10 between two models in- and excluding covariates, the differences may be regarded as negligible. First, we tested the structural model without covariates, χ2(126) = 456.05, p < 0.01; χ2/df = 3.62; CFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.94; RMSEA = 0.06; CIRMSEA = [0.05; 0.07], p < 0.01, which resulted in fit indices comparable to the proposed model with covariates. Comparing coefficients across both models revealed that differences between standardized coefficients were smaller than 0.10, except for integration preference with a 0.13 lower effect magnitude in the model with covariates. Second, as reported above, teaching profession showed particularly strong bivariate correlations with both integration preference and integration behavior. As a result, we tested the structural model with teaching profession as sole covariate. Again, fit indices were acceptable, χ2(139) = 530.98, p < 0.01; χ2/df = 3.82; CFI = 0.95; TLI = 0.94; RMSEA = 0.06; CIRMSEA = [0.06; 0.07], p < 0.01, and differed only negligibly from those of the proposed model with covariates. Differences between standardized coefficients across these two models now differed by less than 0.10, which suggested that controlling for teaching profession impacted the effect of integration preference on integration behavior. A subsequent analysis investigating differential effects of antecedents on integration behavior in teaching professions vs. other occupations suggested no moderating effect of teaching profession, Δχ2(4) = 4.52, p = 0.34. The results of these additional analyses point to a crucial role of the teaching profession in our analyses, which will be elaborated in the discussion.

Discussion

The aim of our research was to apply the RAA in order to shed light on why employees integrate work into their nonwork domain. In doing so, we gained an understanding of the factors that motivate employees’ integration behavior by examining the relationship between individual and organizational antecedents of integration behavior and the respective employee behavior in a manner more comprehensive than that of previous work. Specifically, integration preference, integration norms, and behavioral control were considered as antecedents of employees’ integration behavior. In addition, we examined the differing impact of two distinct types of integration norms on employee integration behavior, namely injunctive and descriptive norms.

On the whole, the results exhibit a meaningful pattern of antecedents of employee integration behavior. All four antecedent factors of the RAA made significant contributions to the prediction. The variance of integration behavior explained by those four factors is comparable to previous RAA research (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). Compared to the other three factors, integration preference was found to be a particularly strong predictor for work-to-nonwork integration behavior. This result implies a strong link between the individual desire how to manage the work–nonwork interface and the resulting behavior. In line with person–environment fit research (e.g., Kreiner, 2006), the results suggest that individuals may anticipate the challenge to actively manage potential incongruence between their work–nonwork boundary management preferences and work characteristics and proactively enter work domains that seem to align with their preferences. Because many characteristics of the work and nonwork domain are difficult to alter, and individuals’ typical integration behavior is relatively stable (Hecht & Allen, 2009), this line of thought may be especially relevant. Noteworthy in this regard is the significant positive correlation between integration preference and descriptive norms. Consistent with the attraction–selection–attrition framework (Schneider, 1987), this could suggest that individuals self-select into organizations that are populated by like-minded people. Furthermore, organizational socialization plays a role in transforming new employees from organizational outsiders into insiders (Bauer & Erdogan, 2011). Therefore, the interrelations between integration preference, descriptive norms, and integration behavior may also be explained, at least in part, by individuals accommodating to organizational norms over time. In line with previous research, a complementary process of a priori selection and ex-post socialization is likely to contribute to this finding (Semmer & Schallberger, 1996).

Compared to descriptive norms, perceived injunctive norms from the organization to integrate work into the nonwork domain were not related to integration preference. Yet, the effect of injunctive norms on integration behavior was about twice as strong as that of descriptive norms. These results suggest that both types of norms contribute to integration behavior by providing information about what is adaptive behavior in the individual’s work–nonwork context (Cialdini et al., 1990). The fact that injunctive norms emerged as a stronger predictor of integration behavior than descriptive norms suggests that perceptions of what one should do are more influential than perceptions of what others, i.e., colleagues and supervisors, actually do. A possible explanation for this finding may be that injunctive norms are associated with social sanctions in case of noncompliance with these norms, whereas descriptive norms are not (Lapinski & Rimal, 2005). Nevertheless, both forms of integration norms contributed uniquely as factors that motivate integration behavior. The superior fit of the 5-factor measurement model and the differing loadings in the structural model suggest the conceptual distinctness of injunctive and descriptive norms. Thus, our results are in line with previous RAA findings and support the distinction between injunctive and descriptive norms as two types of social pressure (e.g., Manning, 2009).

In relation to the explained variances of integration norms and integration preference as antecedents of integration behavior, behavioral control appears to play a more ambiguous role regarding the question why employees integrate. The results of our study imply that merely “feeling in control” to integrate work into the nonwork domain does not indicate its behavioral realization. On the contrary, our results show that perceived control over individual work–nonwork boundaries was associated with less integration behavior. A possible explanation for this finding is that just because a person perceives to have control to carry out a certain behavior (i.e., the person perceives to have the necessary skills and abilities and a favorable work environment) does not automatically imply that the person will also act on the behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). Indeed, while control by itself merely indicates the possibility to realize a certain behavior, the factors that motivate a behavior stem from other sources, such as individual preferences and organizational norms. If preferences and norms coincide, that is, individuals want what organizations expect, control may be of subordinate relevance. If preferences and norms deviate, however, perceived control may be a decisive control unit that determines whether individuals’ behavior will be autonomous (i.e., guided by their preferences) or heteronomous (i.e., guided by norms that do not conform to their preferences).

In our sample, we found evidence for such a deviation between a strong tendency to prefer the segmentation of work from nonwork, and comparably strong perceptions of injunctive norms to integrate work into the nonwork domain. Regarding behavioral control, a rather high overall level was observed. Therefore, employees in our sample were able to pursue their preference to segment and refrain from adhering to injunctive norms, which consequently led to a low integration level. The negative effect of behavioral control on integration behavior, then, may be regarded as an indicator of this process. Conversely, if employees had perceived no or little behavioral control toward integration, we assume that employees’ realized behavior would have been strongly guided by perceived integration norms. Alternatively, the finding of more behavioral control relating to less integration behavior may also, at least in part, be explained by our choice to measure the latter. While we agree with Allen et al. (2014) that our measure does not capture dysfunctional permeations per se, the behaviors described in the items may nevertheless be perceived as disruptive, which is something people are very likely to avoid if they perceive behavioral control over their job, even if they prefer (nondisruptive) integration. Therefore, while a possibly decisive function of behavioral control should be investigated in future studies, particular attention should also be given to item wordings of involved measures.

Following the recommendations of Becker et al. (2016) on dealing with covariates, we performed our analyses both with and without covariates to assess the significance of added background factors to the main study variables. Results of this assessment show a particular impact of employees with a teaching profession in the otherwise heterogeneous sample. This finding suggests that teachers are faced with profession-specific job characteristics and, in a wider sense, that job characteristics of different professional groups affect the varying degree of the antecedents of integration behavior considered here. In our case, teachers’ jobs may be characterized by increased workplace flexibility when it comes to the preparation and follow-up of classes, for example (Cinamon, Rich, & Westman, 2007). The present study focused on a general picture of employees’ motivational factors to integrate work into the nonwork domain, thus analyzing a heterogeneous sample. Against the backdrop of job characteristics as contextual factors that may affect people’s integration behavior, future studies investigating this aspect would be very interesting.

Research Implications

There have been a few previous studies that addressed antecedents of employee integration behavior in a broader sense (e.g., Park et al., 2011; Richardson & Benbunan-Fich, 2011); however, none have employed a strong theoretical framework. In specifying antecedents of integration behavior, we have drawn on the RAA (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010), which has been proposed as a suitable framework to conceptualize the degree to which individual, work, and nonwork factors contribute to work–nonwork integration behavior (Matthews et al., 2016). Our predictors of integration behavior reflect the three RAA domains: attitude toward the behavior, perceived norm, and perceived behavioral control. Taking these elements together, this study makes an important contribution to overcoming what has been criticized as the atheoretical nature of work–nonwork research (Matthews et al., 2016). It provides further evidence for the utility of using established models of human behavior from other fields to inform work–nonwork research.

A further implication of this study relates to the differentiated consideration of perceived organizational integration norms. Partly corresponding to our results that showed a stronger influence of injunctive vs. descriptive norms, Barber and Santuzzi (2015) found injunctive but not descriptive norms to be related to increased technology-related boundary crossing behaviors. This finding of a stronger effect of injunctive norms compared to descriptive norms must be tested in future studies. Interestingly, Derks et al. (2015) found that peer influence (using a mixed injunctive and descriptive norms measure) related stronger to smartphone use after work hours than supervisor influence did (using an injunctive norms measure). Whether this result can be explained by different sources of influence (colleagues vs. supervisor) or by the measure combining both normative aspects (albeit at the cost of differentiated results) should be explored in future studies.

Through the differentiated analysis of integration norms, this study thus adds to our understanding of distinct types of perceived social pressure in work–nonwork research. Since previous research associates social pressure for work in nonwork time with negative consequences for employee well-being (e.g., Höge, 2011; Ohly & Latour, 2014; Park et al. 2011; Piszczek, 2016), further research is needed to identify and act on relevant organizational processes to ensure employee well-being. In regard to perceived norms in general and in line with the RAA, we have focused on two forms of social pressure which originate from inside the organization (employers, supervisors, colleagues). However, further outside sources of social pressure to integrate work into nonwork may exist, for example suppliers, customers, but also society in general (Matusik & Mickel, 2011).

As a final research implication, we would like to refer to the additional evidence on relevant background factors that may impact people’s decisions whether to integrate or not. Specifically, the findings of this study suggest that the relative impact of the antecedents of integration behavior may be subject to a person’s type of occupation, or specific job demands and resources. The influence of people’s job characteristics on integration behavior should be further investigated in future studies.

Practical Implications

Apart from theoretical explanations, several practical implications of the present study exist. First, results of this study indicate that the individual’s desire to integrate is reflected in the person’s degree of integration behavior. However, if the degree of integration behavior shown cannot align with the individual integration preference, this organizational–individual misfit may lead to increased work–nonwork conflict, stress, and decreased job satisfaction (Kreiner, 2006). Therefore, we recommend that people realize the importance of the fit between their individual preferences and organizational norms. If a misfit is identified, employees may seek talks with their supervisor or the HR department to improve their work situation. In addition, individuals looking for a job have the opportunity to obtain information on the integration norms of prospective employers and compare them with their individual preferences in terms of a realistic job preview (Buckley et al., 2002). This step increases the chances to settle into a work environment that aligns with the individual’s preference to manage the work–nonwork interface.

Second, as an explanatory theory, the RAA predicts behavior under defined conditions. In doing so, the RAA may also contribute to practical interventions by providing the “modifiable factors” that should be targeted for change (Kok & Ruiter, 2014). The antecedents of integration behavior examined here represent such factors to consider when developing organizational health interventions and supporting employees in the successful management of the work–nonwork interface. For example, injunctive norms evolve through explicit or implicit organizational policies and procedures, which organizations are able to change. Organizations may address their existing injunctive norms by making organizational integration expectations more conscious and clarifying the level of their prevalence in the organization. It is recommended to discuss existing injunctive norms in order to agree on a level of integration expectations that is acceptable for all parties involved (e.g., employer, employees, suppliers, customers). In this way, organizations can actively develop and shape their injunctive norms around integration behavior. In contrast, because descriptive norms mainly evolve by employee habit, interventions to actively shape descriptive norms will be more difficult. Nevertheless, a possible approach could be the emphasis of role model behavior through company campaigns to stimulate the desired degree of integration or segmentation behavior.

Limitations and Future Research

Finally, the current study was limited in several ways. First, a frequently mentioned limitation concerning common method variance is the collection of individual and organizational data solely based on self-reports. However, common method variance should be less of a concern when self-report measures are appropriate and of prime interest (Conway & Lance, 2010). The focus of the present study was on employee attitudes, individual perceptions of social norms, and perceived behavioral control, all of which are characterized as personal information, and are thus not easily observed through other sources (Conway & Lance, 2010).

Second, the reliance on student-recruited samples may be susceptible to sampling bias. As a preventive measure, we followed guidelines for quality assurance in the process of data collection, e.g., providing clear instructions to recruiters and participants, and raising recruiters’ interest in high-quality data collection (Wheeler, Shanine, Leon, & Whitman, 2014). Moreover, a meta-analysis by Wheeler et al. (2014) indicates that student-recruited samples do not show particular differences to nonstudent-recruited samples. An advantage of a student-recruited data sampling technique is indeed the possibility to secure sample heterogeneity, which was a prerequisite for answering the question raised in this study.

Third, because work–nonwork research is sensitive to context, cultural influence may be a limitation to cross-cultural generalization of the results (Shockley et al., 2017). Clearly, Austria and Germany are comparable in terms of labor policies and the prevalence of flexible work (Kassinis & Stavrou, 2013). However, because the main body of work–nonwork research has been conducted in North America so far (Casper, Allen, & Poelmans, 2013), we regard our results as a valuable contribution to the cultural diversity of work–nonwork research. Nevertheless, the influence of cultural context on the study’s research question compels scrutiny.

In addition to limiting aspects, this research has also identified questions in need of further investigation. First, we applied the RAA to identify antecedents and their combined effects on integration behavior. To advance successful strategies to manage the work–nonwork interface, future research may further disentangle antecedents of work-to-nonwork integration by (1) investigating potential interplays between the factors identified here, (2) relating potential consequences of integration to antecedents and integration behavior, and (3) including the nonwork-to-work direction of integration.

Second, our measurement of attitudes and perceived behavioral control was somewhat limited by the lack of differentiated instruments. We therefore suggest a more comprehensive test of the RAA in future studies by differentiating empirically (1) experiential and instrumental forms of attitudes toward integration and (2) capacity and autonomy as two aspects of perceived behavioral control. Regarding the former, Olson-Buchanan and Boswell (2006) measured emotional reactions to role boundary interruptions, which may serve fruitful for capturing experiential attitudes. As concerns instrumental attitudes, items from challenge/hindrance appraisal measures (e.g., Peacock & Wong, 1990; Webster, Beehr, & Love, 2011) may be adapted to capture whether integration behavior is perceived as having helpful vs. harmful consequences. Regarding perceived behavioral control, we suggest measuring internal capacity in addition to established measures of external autonomy, thereby assessing one’s confidence about being able to achieve a desired goal of integration behavior.

Third, we found meaningful effects of four antecedents of integration behavior. Yet, despite our time-lagged data, statements about causality need to be interpreted with due caution. Of course, the performance of integration behavior and the experience of its consequences form a feedback loop that guides further adjustment of those factors that we modeled as antecedents in this study. Because these feedback loops are also anticipated in the RAA framework (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010), we propose that future studies should specifically address the chain of possibly reciprocal effects of integration antecedents, behavior, and consequences.

Conclusion

In this study, we demonstrated the applicability and utility of the RAA framework for work-to-nonwork integration research. Overall, the proposed model offers new insights into the linkages between integration preference, injunctive and descriptive norms, behavioral control, and employee integration behavior. By looking at potential antecedents of integration behavior, researchers and practitioners alike gain a deeper understanding of the driving forces that motivate work-to-nonwork integration. This understanding may serve as a starting point for a better alignment of individual needs and organizational expectations.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211.

Allen, T. D., Cho, E., & Meier, L. L. (2014). Work-family boundary dynamics. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1, 99–121.

Ashforth, B. E., Kreiner, G. E., & Fugate, M. (2000). All in a day’s work: Boundaries and micro role transitions. The Academy of Management Review, 25, 472–491.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Barber, L. K., & Santuzzi, A. M. (2015). Please respond ASAP: Workplace telepressure and employee recovery. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20, 172–189.

Bauer, T. N., & Erdogan, B. (2011). Organizational socialization: The effective onboarding of new employees. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 51–64). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Becker, T. E., Atinc, G., Breaugh, J. A., Carlson, K. D., Edwards, J. R., & Spector, P. E. (2016). Statistical control in correlational studies: 10 essential recommendations for organizational researchers. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37, 157–167.

Buckley, M. R., Mobbs, T. A., Mendoza, J. L., Novicevic, M. M., Carraher, S. M., & Beu, D. S. (2002). Implementing realistic job previews and expectation-lowering procedures: A field experiment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61, 263–278.

Casper, W. J., Allen, T. D., & Poelmans, S. A. (2013). International perspectives on work and family: An introduction to the special section. Applied Psychology, 63, 1–4.

Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R., & Kallgren, C. A. (1990). A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 1015–1026.

Cinamon, R. G., Rich, Y., & Westman, M. (2007). Teachers’ occupation-specific work-family conflict. Career Development Quarterly, 55, 249–261.

Clark, S. C. (2002). Communicating across the work/home border. Community, Work & Family, 5, 23–48.

Conway, J. M., & Lance, C. E. (2010). What reviewers should expect from authors regarding common method bias in organizational research. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25, 325–334.

Derks, D., van Duin, D., Tims, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2015). Smartphone use and work–home interference: The moderating role of social norms and employee work engagement. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 88, 155–177.

Deutsch, M., & Gerard, H. B. (1955). A study of normative and informational social influences upon individual judgment. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 51, 629–636.

Duxbury, L., Higgins, C., Smart, R., & Stevenson, M. (2014). Mobile technology and boundary permeability. British Journal of Management, 25, 570–588.

Feather, N. T. (1982). Expectations and actions: Expectancy-value models in psychology. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Fenner, G. H., & Renn, R. W. (2004). Technology-assisted supplemental work: Construct definition and a research framework. Human Resource Management, 43, 179–200.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2010). Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. New York: Psychology Press.

Friedman, S. D., & Greenhaus, J. H. (2000). Work and family—Allies or enemies? What happens when business professionals confront life choices. New York: Oxford University Press.

Head, K. J., & Noar, S. M. (2014). Facilitating progress in health behaviour theory development and modification: The reasoned action approach as a case study. Health Psychology Review, 8, 34–52.

Hecht, T. D., & Allen, N. J. (2009). A longitudinal examination of the work-nonwork boundary strength construct. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30, 839–862.

Höge, T. (2011). Perceived flexibility requirements at work and the entreployee-work-orientation: Concept and measurement. Psychology of Everyday Activity, 4, 3–21.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55.

Kassinis, G. I., & Stavrou, E. T. (2013). Non-standard work arrangements and national context. European Management Journal, 31, 464–477.

Kim, T. G., Hornung, S., & Rousseau, D. M. (2011). Change-supportive employee behavior: Antecedents and the moderating role of time. Journal of Management, 37, 1664–1693.

Kok, G., & Ruiter, R. A. C. (2014). Who has the authority to change a theory? Everyone! A commentary on Head and Noar. Health Psychology Review, 8, 61–64.

Kossek, E. E., & Lautsch, B. A. (2012). Work-family boundary management styles in organizations: A cross-level model. Organizational Psychology Review, 2, 152–171.

Kossek, E. E., Ruderman, M. N., Braddy, P. W., & Hannum, K. M. (2012). Work-nonwork boundary management profiles: A person-centered approach. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81, 112–128.

Kreiner, G. E. (2006). Consequences of work-home segmentation or integration: A person-environment fit perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27, 485–507.

Lapinski, M. K., & Rimal, R. N. (2005). An explication of social norms. Communication Theory, 15, 127–147.

Manning, M. (2009). The effects of subjective norms on behaviour in the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Social Psychology, 48, 649–705.

Matthews, R. A., Barnes-Farrell, J. L., & Bulger, C. A. (2010). Advancing measurement of work and family domain boundary characteristics. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77, 447–460.

Matthews, R. A., Wayne, J. H., & McKersie, S. J. (2016). Theoretical approaches to the study of work and family: Avoiding stagnation via effective theory borrowing. In T. D. Allen & L. T. Eby (Eds.), Oxford handbook of work and family (pp. 23–35). New York: Oxford University Press.

Matusik, S. F., & Mickel, A. E. (2011). Embracing or embattled by converged mobile devices? Users’ experiences with a contemporary connectivity technology. Human Relations, 64, 1001–1030.

Mazmanian, M., Orlikowski, W. J., & Yates, J. (2013). The autonomy paradox: The implications of mobile email devices for knowledge professionals. Organization Science, 24, 1337–1357.

McEachan, R., Taylor, N., Harrison, R., Lawton, R., Gardner, P., & Conner, M. (2016). Meta-analysis of the reasoned action approach (RAA) to understanding health behaviors. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 50, 592–612.

Meade, A. W., & Craig, S. B. (2012). Identifying careless responses in survey data. Psychological Methods, 17, 437–455.

Methot, J., & LePine, J. (2016). Too close for comfort? Investigating the nature and functioning of work and non-work role segmentation preferences. Journal of Business and Psychology, 31, 103–123.

Nippert-Eng, C. E. (1996). Home and work: Negotiating boundaries through everyday life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ohly, S., & Latour, A. (2014). Work-related smartphone use and well-being in the evening: The role of autonomous and controlled motivation. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 13, 174–183.

Olson-Buchanan, J. B., & Boswell, W. R. (2006). Blurring boundaries: Correlates of integration and segmentation between work and nonwork. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68, 432–445.

Parasuraman, S., & Greenhaus, J. H. (2002). Toward reducing some critical gaps in work-family research. Human Resource Management Review, 12, 299–312.

Park, Y., Fritz, C., & Jex, S. M. (2011). Relationships between work-home segmentation and psychological detachment from work: The role of communication technology use at home. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16, 457–467.

Peacock, E. J., & Wong, P. T. P. (1990). The stress appraisal measure (SAM): A multidimensional approach to cognitive appraisal. Stress Medicine, 6(3), 227–236.

Piszczek, M. M. (2016). Boundary control and controlled boundaries: Organizational expectations for technology use at the work-family interface. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38, 592–611.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569.

Powell, G. N., & Greenhaus, J. H. (2010). Sex, gender, and the work-to-family interface: Exploring negative and positive interdependencies. Academy of Management Journal, 53, 513–534.

Richardson, K., & Benbunan-Fich, R. (2011). Examining the antecedents of work connectivity behavior during non-work time. Information and Organization, 21, 142–160.

Roberts, K. (2007). Work-life balance—The sources of the contemporary problem and the probable outcomes: A review and interpretation of the evidence. Employee Relations, 29, 334–351.

Rothbard, N. P., & Ollier-Malaterre, A. (2016). Boundary management. In T. D. Allen & L. T. Eby (Eds.), Oxford handbook of work and family (pp. 109–123). New York: Oxford University Press.

Schneider, B. (1987). The people make the place. Personnel Psychology, 40, 437–453.

Schwarzer, R. (2014). Life and death of health behaviour theories. Health Psychology Review, 8, 53–56.

Semmer, N., & Schallberger, U. (1996). Selection, socialisation, and mutual adaptation: Resolving discrepancies between people and work. Applied Psychology, 45, 263–288.

Sheeran, P. (2002). Intention-behavior relations: A conceptual and empirical review. European Review of Social Psychology, 12, 1–36.

Sheeran, P., & Silverman, M. (2003). Evaluation of three interventions to promote workplace health and safety: Evidence for the utility of implementation intentions. Social Science & Medicine, 56, 2153–2163.

Shockley, K. M., Douek, J., Smith, C. R., Yu, P. P., Dumani, S., & French, K. A. (2017). Cross-cultural work and family research: A review of the literature. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 101, 1–20.

Song, Y. (2009). Unpaid work at home. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy & Society, 48, 578–588.

Webster, J. R., Beehr, T. A., & Love, K. (2011). Extending the challenge-hindrance model of occupational stress: The role of appraisal. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79, 505–516.

Wepfer, A. G., Allen, T. D., Brauchli, R., Jenny, G. J., & Bauer, G. F. (2018). Work-life boundaries and well-being: Does work-to-life integration impair well-being through lack of recovery? Journal of Business and Psychology, 33, 727–740.

Wheeler, A. R., Shanine, K. K., Leon, M. R., & Whitman, M. V. (2014). Student-recruited samples in organizational research: A review, analysis, and guidelines for future research. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 87, 1–26.

Zerubavel, E. (1991). The fine line: Making distinctions in everyday life. New York: Free Press.

Acknowledgments

We thank Christine Unterrainer, Severin Hornung, Lisa Hopfgartner, and two reviewers for helpful comments on a previous version of this manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Innsbruck and Medical University of Innsbruck. This work was supported by the DOC fellowship of the Austrian Academy of Sciences granted to Esther Palm.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Palm, E., Seubert, C. & Glaser, J. Understanding Employee Motivation for Work-to-Nonwork Integration Behavior: a Reasoned Action Approach. J Bus Psychol 35, 683–696 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-019-09648-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-019-09648-5