Abstract

Fierce competition coupled with an increasing presence of dual-earning couples and blurred boundaries between work and family, increasingly render work–family lives of employees important. In this context, one strategy to enable employees achieve greater work–family interface is via Family Supportive Supervisor Behaviors (FSSBs), defined as supervisors’ informal discretion to implement family-friendly policies at work. Inspired by the growth in research on FSSBs, the over-arching goal of this study is to explore (a) the triggers of FSSBs from an organizational context perspective and (b) the role of FSSBs as a mechanism to translate the impact of organizational context on subordinates’ overall health and work–family balance satisfaction. Furthermore, we expand our model by integrating the (c) role of supervisors’ and subordinates’ elderly care responsibilities as an individual boundary condition to explain how the FSSBs unfold and for whom they are most effective. Using the Work–Home Resources model (i.e., W-HR model; Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012), we test our hypotheses with matched data of subordinates and their supervisors collected in El Salvador and Peru. Our model was largely supported. Findings point to the importance of organizational and supervisor support as well as the importance of involvement with elder-care responsibilities in driving FSSBs and enhancing employee perceptions of health and their work–family balance satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In today’s work environments, characterized by intense competition and constant pressure to be accessible, employees experience intensifying work–family issues and problems (Kossek, Pichler, Bodner, & Hammer, 2011; Straub, 2012). While organizations adopt and implement supportive policies to alleviate these problems, the supervisors’ role in enabling their employees achieve greater work–family balance and hence create a resourceful work environment is undeniable (Hammer, Kossek, Yragui, Bodner, & Hanson, 2009, Allen, 2001). One such way is exhibiting Family Supportive Supervisor Behaviors (FSSBs), which are informal policies that encompass emotional and cognitive support for subordinates’ family lives, and which entail creative ways of enabling subordinates to enjoy work–family balance (Bagger & Li, 2014; Hammer et al., 2009). In the light of the growing evidence demonstrating the positive impact of FSSBs on employees’ work behaviors (e.g., Rofcanin, Las Heras, & Bakker, 2017) and attitudes (e.g., Odle-Dusseau, Britt, & Greene-Shortridge, 2012), the over-arching goal of this study it to explore the nomological network of FSSBs taking into account the organizational culture as a trigger of FSSBs and domain-specific outcomes. Furthermore, we expand our model by integrating the individual level contextual conditions as boundary conditions. We build on the Work–Home Resource (W-HR; Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012) model as our theoretical framework.

In a growing field of research, studies have mainly focused on the consequences of FSSBs, overlooking the question of what drives supervisors to engage in these behaviors (Crain & Stevens, 2018). Among the few studies that explored the triggers of FSSBs, a predominant focus has been on the characteristics of supervisors (e.g., workaholism, LMX) who engage in FSSBs. Accordingly, our first goal is to introduce an organizational-culture perspective and explore how working in a supportive and unsupportive work environment impacts the FSSBs. Such a focus is important because FSSBs are low cost and informal practices of driving employee performance (Hammer et al., 2009; Crain & Stevens, 2018); thus, understanding the nature and characteristics of organizations that facilitate FSSBs holds strategic importance for organizations and for employees (Hammer, Kossek, Bodner, & Crain, 2013). To capture the former, we introduce a resource angle and integrate perceived organization (POS) support, which is defined as employees’ general belief that their organization values their contribution and cares about their well-being (Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison, & Sowa, 1986; Eisenberger, Stinglhamber, Vandenberghe, Sucharski, & Rhoades, 2002). To capture the latter, we integrate a hindering demand angle and focus on a particular form of work–family culture, in which work is prioritized over family. We refer to it as unsupportive work–family culture, characterized by (a) pressuring employees to work over-time at the cost of their family lives and (b) negative career consequences for employees using family-friendly policies (Thompson, Beauvais, & Lyness, 1999).

Building on one of the core tenets of the W-HR model that resources at work generate further resources in another domain and motivate employees while hindering work demands deplete from one’s resources (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017), we extend FSSB research by exploring two key, yet untested, antecedents from a resource perspective (Craine & Stevens, 2018): POS and unsupportive work–family culture. Our focus on POS is important to cultivate and breed an organizational culture supportive of such informal policies, which are less costly for organizations, and yet effective (Bagger & Li 2014; Russo, Buonocore, Carmeli, & Guo, 2015). Our focus on unsupportive work–family culture is important to inform organizations and HR executives of the potentially negative consequences when work environment is hindering (e.g., Las Heras, Rofcanin, Bal, & Stollberger, 2017).

Our second goal is to explore the mediating role of FSSBs on the association between the organizational culture (i.e., POS and unsupportive work–family culture) and the subordinates’ outcomes: perceived overall health and work–family balance satisfaction. We propose that engaging in FSSBs carries over the positive impact of POS on employees’ overall health and work–family balance satisfaction, indicating a trickling down effect from organizations to subordinates via supervisors. Similarly, but in an opposite direction, the negative impact emanating from an unsupportive work–family culture ripples down to subordinates via FSSBs, signaling that, in such contexts, working long hours and under pressure are prioritized over the employees’ family lives.

A focus on FSSBs as a mediating mechanism between organizational culture and subordinate outcomes, and thus bringing a behavioral perspective, is novel in that it echoes research on the role of supervisors in sense giving, signaling, and implementing various informal HR policies that ultimately impact and shape employees’ performance (McDermott, Conway, Rousseau, & Flood, 2013; Maitlis, 2005; Matthews, Mills, Trout, & English, 2014; Russo et al., 2015). From a trickle-down model perspective, this is, to the best of our knowledge, the first study that (a) explores both a positive and negative route and that (b) takes organizational culture as a starting point, cascading down the hierarchy to impact on the subordinates’ work outcomes. In so doing, we respond to calls to go beyond the dyadic relationship between a supervisor and a subordinate (Wo, Ambrose, & Schminke, 2015) and focus on a wider organizational context in understanding how various family supportive policies are adopted and implemented (Rofcanin, Las Heras, Bal, van der Heijden, & Erdogan, 2018; Bakker, Westman, & Van Emmerik, 2009).

Our third goal is to expand our understanding on the contextual conditions of FSSBs by focusing on supervisors’ and subordinates’ own elderly care responsibilities. Due to prevalence of chronic diseases and disability among older people, there have been increasing demands upon family members to manage both paid work and informal unpaid elder care (Crimmins & Beltran-Sanchez, 2011; Neal & Hammer, 2007). Few studies have revealed that elderly care has been associated with stress and lowered work performance of caregivers (Zacher, Jimmieson, & Winter, 2012). On the contrary, recent studies demonstrate that employees with elderly care responsibilities are likely to understand better the needs of others and, hence, engage in helpful behaviors towards their colleagues (Las Heras et al., 2017). Given the inconclusive results on the impact of elderly care, organizations face the challenge of how to keep employees with elder-care responsibilities motivated and productive (Zacher & Winter, 2011).

Drawing on one of the tenets of the W-HR model that employees equipped with resources (either from work or home) generate further personal resources, (such as positive effect, resilience, and integrating the buffer), boost hypotheses from the J-DR theory (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017), we propose that supervisors who are more (less) involved with elderly care are more (less) likely to exhibit FSSBs, boosting the impact of POS on FSSBs while buffering the impact of unsupportive work–family culture on FSSBs. Similarly, we propose that subordinates who are more (less) involved with elderly care responsibilities are more (less) likely to translate the positive impact of FSSBs on their perceived overall health and satisfaction with work–family life balance (Cameron & Caza, 2004, Carmeli, 2014, Chen et al., 2014).

By conceptualizing elderly care as a resource that generates energy and positive effects for the caregiver (Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012), we contribute to recent research which has started to highlight the importance of care-giving needs as boundary conditions and contextual elements in FSSB research (e.g., Bagger & Li, 2014; Russo et al., 2015) as well as to broader work–family literature (Las Heras et al., 2017; Kossek et al., 2017). Yet, we depart from recent research (e.g., Kim & Gordon, 2014) in turning the limelight to both supervisors’ and subordinates’ elderly care responsibilities and argue how experiencing such challenging family conditions might generate positive personal resources and translate into enhanced work experiences for subordinates (Hammer et al, 2011, Hammer et al, 2007, Hayes, 2013, Hobfoll, 2002).

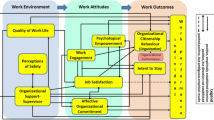

Drawing on the W-HR model (Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012) as a guiding framework, our overall contribution lies in relatively unintegrated literatures on FSSBs, elderly care and organizational culture. We test our conceptual model (depicted in Fig. 1) with matched data collected from subordinates and their supervisors across three companies in El Salvador and Peru. Our study context is a strength and contribution to FSSB research which is dominated mainly by the USA and other Western contexts. Investigating FSSBs in non-Western and resource-cursed contexts such as ours is important, because it fine tunes our understanding of the presence of such behaviors and addresses the question of how they unfold (Xanthopoulou et al., 2007). In the next sections, we develop our hypotheses.

Theory and Hypotheses Development

The Work–Home Resource Model in the Context of Our Study

The W-HR model (Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012) provides the over-arching framework for our study. The model elucidates how enrichment or conflict may occur between the work and home domains, by focusing on the generation or depletion of resources. Contextual resources, such as support from coworkers or leadership, facilitate enrichment while contextual threats, such as hindering work demands, may cause conflict between the work and home domains. Furthermore, the model delineates situational conditions, such as personal resources and energies that strengthen (vs. weaken) the work–home enrichment (vs. conflict). These resources may be objects (e.g., a house), personal characteristics (e.g., health), conditions (e.g., marital status), energy (e.g., mood, physical energy), support (e.g., love), and psychological states (e.g. optimism) that a person values and can be present either in the work or home domain.

As starting points of enrichment between work and home, we focused on POS (as a resource) and work–family culture (time demands and negative consequences of using family-oriented initiatives) as contextual resources. In addition to our focus on POS and work–family culture, we extend the W-HR model by introducing (a) FSSB as a mechanism and (b) elderly care involvement of supervisors and subordinates as contextual conditions to explore our model. We focused on two outcomes: subordinates’ perceived overall health as indication of well-being and subordinates’ satisfaction with work–family balance. We develop our hypotheses in the next sections.

Direct Associations: Unsupportive Work–Family Culture, POS, and FSSBs

We propose that unsupportive work–family supportive culture is negatively associated with FSSBs. One element of unsupportive work–family culture is time demands; they can be quantitative (e.g., the amount of work hours required to complete work tasks either at home or in the work domain) or cognitive (e.g., pressure to prioritize work over home; de Lange et al., 2003) in nature. Such job demands cost time and energy for employees (Crawford et al., 2010) and deplete from their personal resources, such as positive effect (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014). The second aspect of unsupportive work–family culture underscores negative reprimands and costs to one’s career and advancement at work due to participation in work–family initiatives (Thompson et al., 1999). FSSBs refer to managers’ informal discretion to provide employees with family-oriented flexibility so that they can deal with various responsibilities at home (e.g., Lapierre & Allen, 2006; Matthews et al., 2014). These behaviors consist of providing employees with emotional and instrumental support, being role models, and coming up with creative solutions to work–family challenges (Hammer et al., 2009).

The WH-R model underlines that contextual demands and resources are the starting points for enrichment and conflict (Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012). Hindering demands at work cost employees’ time, energy, and focus, thwarting effective task accomplishment (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014). In a work climate where employees work under time pressure and where the completion of tasks is seen as a priority over the family lives of subordinates, managers are less likely to exhibit family-oriented behaviors. This is likely because (over) working with a tight schedule depletes one’s mental, physical and cognitive energy and leaves them with limited (or) no resources to exhibit FSSBs toward their subordinates. Moreover, supervisors working under time pressure are less likely to understand the family needs of their subordinates (i.e., they lack perspective taking and empathy skills to consider their subordinates’ needs). Furthermore, if the work climate is defined by a demanding work schedule (e.g., working during weekends or evenings) and a culture where employees are looked down for promotion when using flexible work practices, supervisors may feel reluctant to exhibit FSSBs because such behavior is not in line with the norms of their culture and may, therefore, backfire on the supervisor. Indirectly supporting this argument, few studies demonstrate that managers who have limited or no knowledge of or access to various work–family benefits present in their organization (Prottas, Thompson, Kopelman, & Jahn, 2007) are less likely to encourage and refer their subordinates to work–family-oriented benefits and programs (Casper, Fox, Sitzmann, & Landy, 2004). These findings suggest that exhibiting FSSBs is influenced by one’s social work setting (Straub, 2012) and, in the context of our study, an unsupportive work–family culture is expected to relate to FSSBs negatively.

Contrary with the direction of the influence of unsupportive work–family culture on FSSBs, we propose that there is a positive association between POS and FSSBs. The W-HR model argues that contextual resources generate enrichment between work and home domains by replenishing personal resources such as motivation, positive effect, or energy (Bakker, Ten Brummelhuis, Prins, & van der Heijden, 2011). Driven by this logic, POS is likely to trigger FSSBs for a variety of reasons. Firstly, POS indicates to employees that the organization cares for their well-being and performance, enhancing their sense of attachment to it (Bhave, Kramer, & Glomb, 2010). A supportive culture, in general, signals that employees are valued in terms of allocating their time and energy for matters above and beyond their work lives and that their well-being is of utmost importance to the organization (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014). This sense of supportiveness creates a positive effect, energy, and motivation for employees. Secondly, the employees’ perceptions of greater organizational support are important, because they (i.e., supervisors) may feel safer in implementing FSSBs and worry less about the others’ reactions to FSSBs. This safety perception emanating from the perception of overall organizational support is likely to relate to their willingness to implement FSSBs to contribute to the employees’ self-growth opportunities and their well-being (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). We thus set our first hypothesis as below:

H1A. Unsupportive work–family culture is negatively associated with FSSBs.

H1B. POS is positively associated with FSSBs.

Direct Associations: FSSBs and the Subordinates’ Outcomes

In exploring the consequences of FSSBs, we focus on the employees’ perceived overall health and their satisfaction with work–family balance. Our focus is driven by research on FSSBs (Straub, 2012; Russo et al., 2015) and work–family interface research (van Steenbergen & Ellemers, 2009), which underscore the need to capture the well-being consequences of FSSBs (i.e., self-rated perceived health as indication of morbidity and longevity; Idler & Benyamini, 1997) and how FSSBs may impact on the employees’ non-work lives (i.e., satisfaction with work–family balance).

FSSBs refer to discretionary supportive behaviors exhibited by supervisors towards the employees’ family roles (Hammer et al., 2013). Emotional support (e.g., expressing concern and care regarding how work impacts on employees’ family and personal life commitments), instrumental support (e.g., providing day-to-day resources to enable employees to address work–family demands), role modeling (e.g., exemplary behaviors, such as enjoying a balanced work life) and creative work–family management (e.g., re-scheduling work in a way that employees can take of their commitments at home) are resources which contribute to the development of emotional, physical and cognitive resources (Hammer et al., 2015). These resources can then be diverted towards increasing their engagement in and satisfaction with domain-related activities (Hammer et al., 2009), driving the employees’ satisfaction with work-life balance.

The display of FSSBs also indicates that supervisors care about the needs and well-being of their subordinates by providing them with the platform to allocate time and energy to their lives beyond the family, enhancing their overall health. FSSBs also signal to the employee that supervisors are empathetic, accessible and have good will to help employees handle family-related problems (Koch & Binnewies, 2015). This can expand one’s overall health positively as employees work in an environment where they can freely exchange their problems and needs with their supervisors without the risk of being reprimanded for this. In support of the positive impact of FSSBs on the employees’ functioning at work, studies have demonstrated that FSSBs impact on work performance (Rofcanin et al., 2017), job satisfaction lowered turnover intentions (Hill, Matthews, & Walsh, 2016), as well as thriving at work (Russo et al., 2015). Extending these studies to include the overall health of employees which encompasses the summary assessment of one’s health and their satisfaction with work–family balance, we set our second hypothesis as:

H2A. FSSBs are positively associated with the overall perceived health of employees a

H2B. FSSBs are positively associated with the employees’ satisfaction with work–family balance satisfaction.

Indirect Associations: the Mediating Role of FSSBs

We further argue that FSSBs constitute mechanisms that mediate the associations between organizational culture and the subordinates’ work outcomes. We build on the gain spiral principle of the W-HR model (Ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012), which underlines that people with more resources are also more capable of resource gains. The initial resource gains, thus, lead to future resource gains, referring to as “gain cycle” between the work and home domains. Regarding time demands, working in an environment where employees are pressured to work long hours and in which the priority is work over their family lives (e.g., time demands), managers are less likely to engage in FSSBs because demonstrating such behaviors does not align with the norms and culture of the organization, and even if they are implemented, they are less likely to be effective (Straub, 2012). Furthermore, in a time-demanding culture, supervisors may feel they have fewer resources with which to support employees and, thus, be more constrained in the ways and willingness to exhibit FSSBs. In turn, lack of FSSBs indicates a lack of emotional, cognitive, instrumental, and other creative resources that supervisors make available to their subordinates to enable them achieve better work–family balance (Hammer et al., 2015). Not having access to these family-oriented resources is likely to impact negatively on the subordinates’ work–family balance and well-being. To illustrate this, one can imagine a work context, in which supervisors pressure their subordinates to work late from their homes or where supervisors are not accessible to discuss issues related to their subordinates’ family problems. These two contexts represent a lack of FSSBs and working in such contexts is likely to thwart the subordinates’ work–family balance and overall health negatively (Hammer et al., 2009).

On the contrary, managers working in supportive organizations are likely to feel secure in implementing FSSBs. They also acknowledge that their organization values the employees’ family lives. This is because high POS suggests that organizations care for the well-being of their employees and are likely to implement any programs to boost their well-being and health (Eisenberger et al., 2009). Working in a resourceful context where subordinates have access to family-oriented resources through FSSBs, subordinates are likely to feel valued, cared for and flexible in addressing their family issues and talking with their supervisors openly and in a trust-driven work environment when it comes to family matters. These employees are likely to perceive that they have resources at their disposal, including social support from work, that they can build on to address as they perform their work and family roles (Russo, Shteigman, & Carmeli, 2016). Receiving emotional, instrumental, and cognitive support from their supervisors and benefiting from creative ways to deal with issues around work–family interface (Hammer et al., 2009), these employees are likely to feel satisfied with the way they divide work and family and develop a positive sense of well-being.

While research on FSSBs has mainly focused on the consequences of this construct, overlooking its potential role as a mechanism, related research on work-life interface provides indirect support for our argument: In their study, Russo et al. (2016) demonstrated that work-life balance mediates the positive associations between perceived supportiveness of organizations, (measured as perceived workplace support and perceived family support) and thriving at work. The findings in Greenhaus, Ziegert, and Allen (2012) revealed that work interfering family (WIF) mediates the positive association between FSSBs and work-life balance. We extend research on FSSBs by drawing on its role as a mediating mechanism and set our third and fourth hypotheses as below:

H3. FSSBs mediate the negative association between unsupportive work–family culture and the perceived overall health of employees (3A), as well as between unsupportive work–family culture and their satisfaction with work–family balance (3B).

H4. FSSBs mediate the positive association POS and the overall perceived health of employees (4A), as well as between POS and their satisfaction with work–family balance (4B).

The Moderating Role of Elderly Care Responsibilities

Supervisors’ Elderly Care Responsibilities as First-Stage Moderator

We expand our model by integrating the moderating role of the supervisors’ elderly care responsibilities into the associations between an unsupportive work–family culture, POS, and FSSBs. The W-HR model emphasizes the role of personal resources—the individuals’ positive self-evaluations and a sense of ability to control and impact upon their environment successfully (Hobfoll, Johnson, Ennis, & Jackson, 2003)—in facilitating the enrichment between the work and family domains. Guided by this logic, we propose that the positive association between POS and FSSBs will be stronger for supervisors with (high) elderly caregiving responsibilities.

The W-HR suggests that the benefits associated with certain resources are boosted when aligned with personal resources such as resilience, self-confidence, or positive self-evaluations. In the context of this study, elder caregiving can be among the most challenging family responsibilities, since—although it can be rewarding—it can also be physically and emotionally taxing (Kim & Gordon, 2014). Yet, dealing with it can lead to the generation of personal resources, such as empathy and taking the perspective of other people’s needs. From a perspective-taking angle (Batson & Shaw, 1991), research has demonstrated that perspective taking is positively associated with directing the attention to other employees, helping them (e.g., helping colleagues; Bakker & Demerouti, 2009), and addressing their work needs (Batson & Shaw, 1991). Drawing on this line of thinking, supervisors, who have elderly caregiving responsibilities and who work in a supportive work environment, are better equipped to translate the potentially rewarding and positive impact of a resourceful and supportive work environment into FSSBs. These supervisors are not only able to put themselves in the shoes of their subordinates (i.e., high elderly care) but also perceive that the overall organization is supportive and cares for the employees’ well-being (i.e., high POS); they are, thus, likely to engage in more FSSBs. As such, supervisors who perceive organizational support to be higher may feel more comfortable in making full use of their informal discretion and decision making powers (e.g., implementing FSSBs), because they observe that the organization as a whole is concerned with the well-being of its employees and values their contributions (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002). The supervisors’ perceptions of greater organizational support are crucial, as they may feel safer in exhibiting FSSBs to care for the well-being and family lives of their subordinates (Las Heras et al., 2017). As a consequence, we argue that supervisors who are involved in elderly care responsibilities and who work in supportive organizations, are likely to exhibit more FSSBs.

We also argue that the supervisors’ elderly care responsibilities buffer the negative association between unsupportive work–family culture and FSSBs. The buffer hypothesis from the JD-R theory states that the costs associated with high hindering work demands are likely to be buffered with sufficient personal resources that the employees have, because these resources enable efficient coping with taxing work conditions (Bakker, Demerouti, & Euwema, 2005; Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). Juggling with their own elderly caregiving responsibilities in a demanding work environment (i.e., high elderly care responsibilities in an unsupportive work–family culture), these supervisors are more likely to understand and acknowledge the family-oriented needs of their subordinates. This is mainly because they have experienced similar hurdles (e.g., working under time pressure at home while dealing with caregiving tasks and being looked down for promotion for using a flexible schedule) and have created a more functioning work environment. They realize that their subordinates need flexibility in terms of addressing their own family needs (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). Working in a work environment where work is prioritized over one’s family, these supervisors are likely to engage in informal support mechanisms such as FSSBs, because they acknowledge that the organization is not supportive of their family lives. Engaging in FSSBs could be one way to translate the overall work environment into a supportive and resourceful work context (Hall, Dollard, Winefield, Dormann, & Bakker, 2013). Thus, these supervisors are likely to exhibit more FSSBs, which buffers the negative association between unsupportive work–family culture and FSSBs. In other words, the supervisors’ elderly care responsibilities prevent the conflict between an unsupportive work–family culture (i.e., time demands—negative consequences of using flexible work practices) and FSSBs. In support of our buffer argument, the study by Tadic, Bakker, and Oerlemans (2015) shows that personal resources buffer the negative association between hindering work demands and work engagement. Xanthopoulou, Bakker, and Fischbach (2013) show that emotional demands and emotional dissonance negatively relate to work engagement when self-efficacy is low (but this negative association does not weaken when self-efficacy is high). Finally, using the J-DR theory, Van Woerkom, Bakker, and Nishii (2016) reveals that personal resources (e.g., strengths use) buffer the negative impact of hindering work demands on employee well-being.

Drawing on the above lines of thinking and the research indicated, we propose that the supervisors’ elderly care responsibilities not only amplify the positive association between POS and FSSBs (boosting effect), but they also buffer the negative association between an unsupportive work–family culture and FSSBs (buffering effect). We thus hypothesize the following:

H5A. The positive association between POS and FSSBs will be moderated by the supervisors’ elderly care responsibilities, such that this association will be stronger for supervisors with higher levels of elderly care involvement.

H5B. The negative association between an unsupportive work–family culture and FSSBs will be moderated by the supervisors’ elderly care responsibilities, such that this association will be weaker for supervisors with higher levels of elderly care involvement.

Subordinates’ Elderly Care Responsibilities as Second-Stage Moderators

Furthermore, we propose that for subordinates with elderly care responsibilities, the positive impact of FSSBs on their overall health and work–family satisfaction is likely to strengthen. Elderly care responsibilities are usually focused on the declining health and death-related problems of parents, which negatively impacts on the well-being of caregivers (Gillespie, Barger, Yugo, Conley, & Ritter, 2011). As such, elderly care can thwart the employees’ functioning at work, because it usually focuses on the declining life cycle of parents, who require time, energy and attention (e.g., dealing with their medical problems, providing emotional, cognitive, and financial support to them; Cavanaugh, Boswell, Roehling, & Boudreau, 2000). In this regard, the resources offered by FSSBs may be useful for these employees to develop personal resources, manage stress, and deal with elderly care effectively (Kossek, Colquitt, & Noe, 2001). From this angle, FSSBs may alleviate the burden of elderly care for these subordinates by providing a platform where these employees benefit from FSSBs; for example, in a work context where they can discuss family-related issues with their supervisors, benefit from family-oriented flexible work schedules without jeopardizing their careers, and receive instrumental support to learn how to deal with the caring needs of the elderly (Hammer et al., 2009). Thus, subordinates who are caregivers of their elderly parents are more likely to make use of FSSBs, with positive downstream consequences on their overall health and satisfaction with their work-life balance (Zacher & Schulz, 2015).

However, we propose that for subordinates who are not involved in caring for their elderly parents, the positive associations between FSSBs and work outcomes are not likely to change. Elderly care responsibility is a challenging, yet only one aspect of family life; other demanding family situations may include childcare, spouse care, or the time that is needed to devote to one’s personal hobbies or other personal development opportunities (Kossek et al., 2017). The enactment of FSSBs may contribute to these intricacies of the subordinates’ family life, impacting on their outcomes positively. To illustrate this, one can imagine a work context, in which a focal employee can take certain afternoons off to take care of his or her toddler at home. This is likely to impact positively on the health and work–family satisfaction of this focal employee. One can also think of a work context, in which a focal employee can discuss with and ask for solutions from his or her supervisor about the specific physical needs of his or her partner. Irrespective of whether these employees are engaged with elderly care responsibilities or not, the display of FSSBs is likely to be positively associated with the subordinates’ outcomes. Our last hypotheses are:

H6. The positive association between FSSBs and the subordinates’ outcomes (overall health and satisfaction with work–family balance) will be moderated by their elderly care responsibilities, such that these associations will be stronger for subordinates with higher levels of elderly care involvement.

Methods

Procedure and Sample

Through the involvement of a European Business School, we have gathered matched supervisor–subordinate data via an on-line survey from two companies (one operating in financial services and one operating in financial services) in El Salvador and one retail company in Peru. One of the authors sent links to the survey via e-mail using e-mail addresses of employees provided by the companies. We used two different on-line surveys, one for the subordinates and one for their supervisors. As the local language in El Salvador and Peru is Spanish, we translated the scale items from the original English version to Spanish using back translation (Brislin, 1986). Participants received two reminders over the course of 2 weeks. We invited 520 supervisors and 1340 subordinates to participate in the study. Due to missing data, in the end, we regained and used matched data from 346 supervisors and 822 of their subordinates. The overall response rate was 67% for supervisors and 61% for subordinates.

Of the subordinate sample 58% were female. The mean age was 34.88 (SD = 9.26) and, on average, they have 1.05 children (SD = 1.06). Of the supervisor sample 47% were female. The mean age was 42.20 years (SD = 9.17) and, on average, they had 1.48 children (SD = 1.11).

Measures

Except for the supervisors’ elderly care responsibilities, all questions were measured by subordinates on a 7-point Likert scale.

Unsupportive Work–Family Culture-Time Demands and Negative Consequences

We assessed unsupportive work–family culture (time demands and negative consequences) using a nine-item measure developed by Thompson et al. (1999). Four items capture time demands. The following is an example of one item: “To get ahead in this organization, employees are expected to work for more than 50 h a week, whether at the workplace or at home.” Five items capture the negative consequences of using work–family-oriented initiatives. One example item is the following: “To turn down a promotion or transfer for family-related reasons will seriously hurt one’s career progress in this organization.” We aggregated items to an average score to represent unsupportive work–family culture. Higher scores indicate a lack of a family supportive culture. α = .85.

POS

To assess positive organizational support (POS), we used the four-item measure developed by Shore and Wayne (1993). Sample items include, “When I have a problem the organization tries to help me.” α = .93.

FSSBs

Subordinates evaluated the FSSBs of their supervisors using the FSSB-Short Form (Hammer et al., 2013). These four items tap into the multiple underlying dimensions of FSSB. The first item, “Your supervisor makes you feel comfortable talking to him/her about your conflicts between work and non-work” captures the dimension of emotional support. The second item, “Your supervisor demonstrates effective behaviors in how to juggle work and non-work issues” assesses the role-modeling dimension of FSSB. The item “Your supervisor works effectively with employees to creatively solve conflicts between work and non-work” evaluates the instrumental support dimensions of FSSB. And the final item, “Your supervisor organizes the work in your department or unit to jointly benefit employees and the company” taps the creative work–family management dimensions of FSSB. We aggregated these four items to an overall FSSB value. α = .95.

Supervisors’ and Subordinates’ Elderly Care Responsibilities

We gathered data from the supervisors and their subordinates to assess the extent to which they are involved with elder care. We measured elderly care involvement by counting the number of ways in which a supervisor (or a subordinate) is involved in caring for one or more of his or her parents (mother, father or both), for natural and in-law parents, giving a combination of six. They indicated whether they help each living parent to fulfill a variety of needs. These needs include: medical care (e.g., taking them to the doctor), social life (e.g., driving them to events), financial (e.g., helping them pay bills and budget), and emotional help (e.g., speaking with the parents by phone to help them feel connected). Scores could, thus, range from 0 to 24. To illustrate this, we can give an example of a supervisor, who may help her mother set a monthly budget and pay bills (e.g., financial help) as well as take her to medical appointments and help coordinate her mother’s care with the doctor (e.g., medical help). This same employee may also help her father-in-law feel connected by calling him once a week (e.g., emotional help). This supervisor would, thus, have a score of 3 on this measure. Supervisors exhibited a range of scores on elder care, from a low of 0 to a high of 8, 289 out of 346 (84%) had elder-care responsibilities (88% in company A, 80% in company B, and 82% in company C), with an average of 1.84. Subordinates also exhibited a range of scores between 0 and 8, 649 out of 822 (79%) had elder-care responsibilities (77% in company A, 67% in company B, and 87% in company C), with an average value of 2.

Perceived Overall Health

We evaluated perceived overall health with the following question: “How do you rate your health compared to other people your age?” Respondents answered using a 7-point Likert scale (1—poor, 7—excellent). Our choice of one-item measure was guided by recent research which underlines that the specific item we used is reliable and valid (de Salvo et al., 2006), and that this approach of utilizing single items is suggested to reduce participant exhaustion and increase retention rate (Cunny & Perri, 1991; Wilson, Dejoy, Vandenberg, Richardson, & Mcgrath, 2004).

Work–Family Balance Satisfaction

We measured the subordinate’s satisfaction with work–family balance with five items from a scale developed by Valcour (2007). The subordinates were asked to indicate their level of satisfaction with regard to five work-life-related areas. A sample item is the following: “The way you divide you time between work and personal or family life”. α = .95.

Controls

In all analyses, we controlled the supervisor’s age, marital status, number of children, hours worked, proportion of time spent caring for children, proportion of time spent doing housework, and gender. Gender can play an important role in how individuals experience their family roles. Women often take on more of the work involved with caring for children and other family responsibilities (Rothbard & Edwards, 2003); this increased involvement in the family role can lead to a greater importance placed on it (Aryee & Luk, 1996). Women leaders are typically described, and expected to be, as communal. Communal behaviors include expressing affection with words and gestures, listening attentively to the other, compromising a decision, complimenting or praising the other person, smiling and laughing with the other, and being emotionally stable (Kidder & McLean Parks, 2001; Marinova, Moon, & Van Dyne, 2010). On the other hand, men are expected to be agentic. Agency includes being achievement-orientated, taking charge, being autonomous and rational; these are considered to be male-gendered workplace behaviors (Kidder & McLean Parks, 2001; Marinova et al., 2010). As these differences in behavior may shape how supervisors are perceived in the workplace, it is important to place control on gender. The supervisor’s gender is represented by 0 for men and 1 for women. Lastly, we controlled the size of the group of subordinates that the supervisor managed.

Analytical Procedure

Due to the nested structure of our data, (the subordinates reporting to supervisors and evaluating FSSBs on their behalf), we utilized multi-level regression analyses (MLWIN) to rule out potential biases emanating from the hierarchical relationship in our data set. In order to evaluate whether multi-level modeling was the right approach, we calculated ICC (1) values for variables rated on behalf of supervisors and for supervisor-rated variables (Hox, 2002): 16% of variance for FSSBs is attributable to hierarchical relationship between the subordinates and their supervisors. These findings suggested that it was appropriate to use multi-level analysis. To adequately control both within-group and between-group variances, we used grand-mean-centered estimates for all level 1 predictors, and unit-level mean-centered estimates for all level 2 predictors (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002).

To test our mediation hypotheses, we conducted Monte Carlo simulations with 20,000 iterations to obtain confidence intervals for our proposed indirect effects (Preacher, 2015). To test our moderation hypotheses (Hu & Bentler (1999), using Dawson’s (2016) suggestions to interpret the results, we plotted simple slopes at one standard deviation above and below the mean of the moderator (Aiken & West, 1991); Bauer et al., 2006; Behson, 2002.

Findings

Table 1 displays the correlations, means, and standard deviations for the study variables.

Hypothesis 1 proposed that unsupportive work–family culture is negatively associated with FSSBs while POS is positively associated with FSSBs. The results support our hypotheses (H1A: γ = − 0.17 (0.03), p < 0.001 for unsupportive work–family culture; H1B: γ = 0.46 (0.03), p < 0.001 for POS). Hypothesis 2 proposed that FSSBs are positively associated with the perceived overall health and work–family balance satisfaction of subordinates. After controlling of POS and unsupportive work–family culture, the results support this hypothesis (H2A: γ = 0.08 (0.02), p < 0.001 for perceived overall health; H2B: γ = 0.08 (0.03), p < 0.001 for work–family balance satisfaction). Hypotheses 3 and 4 proposed that FSSBs mediate the associations between unsupportive work–family culture, POS and the subordinates’ outcomes. FSSBs mediated the positive associations between POS and perceived overall health (Sobel test, 3.77; p < 0.001; 95% CI = [0.018/0.055]) as well as POS and work–family balance satisfaction (Sobel test, 2.59; p < 0.001; CI = [0.009/0.065]). Hypothesis 3 is accepted. FSSBs also mediated the negative associations between unsupportive work–family culture and perceived overall health (Sobel test, − 3.26; p < 0.001; 95% CI = [−0.022/− 0.006]) as well as unsupportive work–family culture and work–family balance satisfaction of subordinates (Sobel test, −2.41; p < 0.05; 95% CI = [− 0.025/− 0.003]) lending support to hypothesis 4 (see Table 2 for details).

Hypothesis 5 proposed that the supervisors’ elderly care involvement moderates the associations between POS and FSSBs as well as an unsupportive work–family culture and FSSBs. The results do not support this hypothesis: The interaction term is not significant for both POS (γ = − 0.01 (0.02; n.s.), and for the unsupportive work–family culture (γ = 0.02 (0.02); n.s.). Hypothesis 5 is not supported (Table 3).

Hypothesis 6 proposed that the subordinates’ elderly care involvement moderates the associations between FSSBs and the subordinates’ outcomes. The results partially support this hypothesis as the interaction term is not significant for the subordinates’ work–family balance satisfaction (γ = 0.008 (0.01); n.s.), but it is significant for the subordinates’ overall health (γ = 0.03 (0.01); p < 0.01). Fig. 2 depicts that for subordinates with high levels of elderly care involvement, the positive association between FSSBs and their overall health is stronger (gradient = 0.19, t = 2.02, p < 0.05). This association is still significant for subordinates with low levels of elderly care involvement (gradient = 0.12, t = 2.21, p < 0.05).

Discussion

Our findings show that POS and unsupportive work–family culture (time demands and negative consequences of using work–family initiatives) negatively relate to FSSBs (H1) and FSSBs are positively associated with the overall health and work–family balance satisfaction of employees (H2). Our findings also support the argument that FSSB is a mediator between unsupportive work–family culture and POS on one hand, and the subordinates’ outcomes, indicting a trickle-down model from organization to supervisors with downstream consequences for subordinates (H3 and H4) on the other hand. With regard to the role of context, our findings provide support that for subordinates with elderly care responsibilities, the positive association between FSSBs and the overall perceived health is made stronger (H6), providing partial support for the moderating role of elderly care responsibilities in our conceptual model. Contrary with our expectations, our results do not support the moderating role of the supervisors’ elderly care responsibilities (H5) on the association between context at the organizational level and FSSBs. We discuss the theoretical contributions below.

This study extends the growing literature on FSSBs in a number of ways. First of all, our findings demonstrate that the presence of a supportive and resourceful work environment (POS) enables FSSBs, while time pressure and negative consequences of using work–family initiatives prevent the display of FSSBs (Bakker & Demerouti, 2003; Bakker & Sanz-Vergel, 2013). This finding deepens our knowledge of the antecedents of FSSBs (Crain & Stevens, 2018) and addresses the lack of empirical evidence particularly from an organizational culture perspective (Rofcanin et al., 2017). Understanding what drives FSSBs is crucial in the light of the evidence that they constitute practical and relatively less-costly interventions that organizations can capture to drive the subordinates’ functioning at work (Kossek et al., 2017; Bond et al., 2006; Burch et al., 2018).

Furthermore, FSSBs constitute resources translating the impact of POS and unsupportive work–family culture on the subordinates’ outcomes. While research to date has mainly focused on the consequences of FSSBs, understanding the mediating role of FSSBs is key as it signals the role of supervisors as enablers of family-friendly behaviors and may trigger a work environment where subordinates look up to and learn from their supervisors (Russo et al., 2015). Previous research has mainly focused on work–family balance (Aryee, Walumbwa, Gachunga, & Hartnell, 2016), work–family enrichment or work–family satisfaction (Qing & Zhou, 2017) as mediating mechanisms between various enabling resources at work (e.g., organizational culture, family supportive culture) and employee outcomes (e.g., work performance, work engagement). Our focus on FSSBs as a mechanism extends this body of literature by pointing out to the informal role of supervisors in displaying family supportive behaviors (Hammer et al., 2015) and, therefore, underscores the trickling down effect from supervisors to their subordinates in enhancing their overall health and the work–family satisfaction of their subordinates. By focusing on the resource-mechanism role of FSSBs, we also contribute to research on trickle-down models which explore how positive experience cascades down from upper to lower levels of hierarchy (Wo et al., 2015). The findings in Rofcanin et al. (2018) reveal that the supervisors’ support trickles down to the subordinates’ performance and promotability via its influence on the subordinates’ family performance. The results in Las Heras et al. (2017) reveal that supervisors’ elderly care trickles down to impact on the subordinates’ use of flexible work practices, with downstream consequences on their work performance. By focusing on and integrating a supportive and unsupportive work context as antecedents to FSSBs, we expand this body of research (Demerouti et al., 2001, Demerouti et al., 2001, Dupré & Day, 2007, Eby et al., 2005).

A second way through which our study extends FSSB research is our focus on elderly care responsibilities. With regard to the role of the subordinates’ elderly care responsibilities, our findings reveal that the positive association between FSSBs and the subordinates’ overall health strengthens in subordinates who have more elderly care responsibilities. This finding is in line with the research conceptualizing elderly care as a hindering situation, which requires compensation with additional resources from work to enable these employees to deal with stress associated with elder care (Kim & Gordon, 2014; Kossek et al., 2017). Indeed, in their recent review on elderly care responsibilities, Calvano and Dixon (2015) show that taking care of the elderly is resource depleting and that supportive resources at work may create an enrichment effect for these employees, who deal with elderly care. In this sense, work may become a protective factor, because it bolsters a care-giver’s sense of self-efficacy, confidence, and belonging to an organization (Zuba & Schneider, 2013). While in our research, we have not measured these underlying assumptions, we suggest future research to explore how the depleting impact of elderly care is buffered with resources from work (Frone et al., 2011, Grawitch et al., 2006, Greenhaus & Kossek, 2014).

However, how employees view elderly care may also depend on the appraisal process and we suggest future research to explore whether elder care is viewed as a challenge or a hindrance situation for employees (Staufenbiel & König, 2010). The subordinates’ elderly care does not moderate the association between FSSBs and their satisfaction with work–family balance. This may be explained by the fact that FSSBs address various family needs of subordinates above and beyond those associated with elderly care (Hammer et al., 2009). Thus, irrespectively of having elderly care or not, the display of FSSBs still bears positive impact on the extent to which the subordinates achieve and feel satisfied with their work–family balance.

This finding has important theoretical implications as it echoes previous research showing that FSSBs are more beneficial for employees who need care. In a recent review study on the implications of elderly care, Calvano and Dixon (2015) call for more research to explore how and why elderly care could be viewed as a resource and enrich the lives of those who have elderly care. Furthermore, our findings contribute to recent debates integrating FSSBs and elderly care. The findings in Russo et al. (2015) reveal that FSSBs are more effective and salient for employees who need care (e.g., who like to be taken care of and spend time with those who care for them). The results in Matthews et al. (2014) point out that FSSBs are more effective for employees with dependent care responsibilities. Our findings expand this line of research by turning the focus on the subordinates’ elderly care involvement (rather than being in need of care) and underscoring that elderly care involvement may indeed be compensated by the existence of work resources, here FSSBs. Indeed, previous research has rarely considered individual factors as moderators in relation to FSSBs, focusing more on organizational factors (Bagger & Li, 2014). From this perspective, this research responds to calls for studies to explore other individual-level contextual conditions, when it comes to explore the consequences of FSSBs (Straub, 2012; Russo et al., 2015).

Interestingly, our hypothesis in relation to the moderating role of the supervisors’ elderly care responsibilities was not supported. It may be that in work environments (a) where employees are valued and cared for (high POS) and (b) where employees are reprimanded for the use of family-oriented work practices (lack of work–family culture), supervisors with high elderly caregiving responsibilities may already acknowledge that exhibiting more or less FSSBs does not make a difference to the benefit of their subordinates. This is because in one way or another, a supportive and resourceful organizational context signals that employees’ family lives and well-being are prioritized (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002). On the contrary, a work context which does not support family-friendly policies signals to employees that their family lives are not prioritized (Thompson, Jahn, & Kopelman, 2004). In such extreme contexts, supervisors may have limited resources and informal power to engage in FSSBs to support their subordinates. Indeed, previous research shows that in strong organizational contexts, the supervisors’ sense-giving roles may be over-ridden by organizational culture, reflecting their inability to implement informal flexible policies (e.g., Maitlis, 2005; McDermott et al., 2013).

The context of this study can also be considered a strength. While previous research on FSSBs and work-life interface in general has been dominated by the context of the USA, this study is unique in that it represents non-USA, less-developed contexts: El Salvador and Peru (Las Heras, Trefalt, & Escribano, 2015). A common denominator of these two countries is the importance placed on family ties and relationships (Annavarjula & Das, 2013; Ollier-Malaterre, Valcour, den Dulk, & Kossek, 2013). Yet, these countries are also resource-cursed, meaning that operating within a macro-economic environment defined by uncertainty, these companies may cut on and limit the implementation of flexible work practices as means of maintaining financial stability. In that regard, employees who receive FSSBs may perceive such practices as something of value (rather than something they are entitled to), which may signal a high-quality relationship between supervisors and subordinates and which may, therefore, explain why the supervisors’ elderly care involvement buffers the negative association between time demands and FSSBs.

A final strength of this study is its extension of the W-HR model. Drawing on the W-HR model, a recent study by Du et al. (2017) reveals that homesickness, conceptualized as a contextual resource, attenuates the positive association between job resources (feedback and social support) and work performance (task and contextual performance). The authors argue that homesickness depletes a focal employee’s time, energy and other personal resources, hence diminishing work performance. In another study, building on the W-HR model, Las Heras et al. (2017) demonstrates that high hindering work demands deplete one’s resources at home, preventing the gain spiral between the home and work domains. The way we hypothesized for the moderating role of the subordinates’ elderly care responsibilities is similar to these studies; high levels of elderly care responsibilities may deplete a focal employee’s limited resources and this negative impact on the subordinates’ outcomes may be compensated by the provision of work resources (i.e., FSSB) to subordinates.

Limitations and Future Research Suggestions

As in all studies, this study has some limitations. Firstly, the sample used in our study is cross-sectional in nature, preventing us to test the causal claims among our proposed associations (see: Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). Future research can contribute to our understanding by collecting data in multiple waves and testing our hypothesized model. Secondly, a related limitation is that we measured perceived health using a single item, as perceived by the subordinates. This is in line with previous research (Goh, Pfeffer, Zenios, & Rajpal, 2015; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014); however, the use of multi-item measures for health will add to the rigor of studies on FSSBs. As a further limitation, we have not measured some of the underlying processes and mechanisms defining our research model and hypotheses. For example, we have not measured whether supervisors develop personal resources, such as resilience, that weaken the association between the work–family culture and FSSBs. Future research is suggested to test these mechanisms (Perlow, 1998, Perlow et al.,2004, Thompson & Prottas, 2006, Voydanoff, 2005, Westman et al., 2008).

As a further point of limitation, we focused only on the elderly care responsibilities of our participants (i.e., managers and their subordinates) and not on other types of care, such as childcare. Our choice was driven by two reasons. Firstly, the nature and characteristics of elderly care are different from taking care of children in that the former is emotionally and physically more demanding and taxing compared with the latter (Williams et al., 2011; James, Andershed, & Ternestedt, 2009). As a result of the demanding nature of elderly care, these caregivers exhibit stress and lowered well-being (Duxbury, Higgins, & Smart, 2011). However, recent research reveals that the impact of elderly care on employee outcomes is mixed: A stream of research unravels positive outcomes while another stream of research reveals negative outcomes (Calvano & Dixon, 2015). To contribute to these discussions and to understand better how elderly care responsibility translates into work outcomes, we focused solely on elderly care responsibilities. Secondly, there is growing evidence across the globe, showing that an increasing number of adults are working and caring for adults at the same time (Calvano & Dixon, 2015; UK, 17%; the USA, 22% with similar patterns observed in the European continent). Such a situation creates pressure on employers with regard to how they can keep caregivers motivated and productive at work while also allowing them to take of their elderly. Future research is suggested to explore how childcare responsibilities, separately and in combination with elderly care (i.e., a focal employee who is taking care of both children and elderly), is likely to play a role in translating the impact of FSSBs on employee outcomes. A resource enrichment and conflict perspective can be integrated in exploring such impacts (Jones et al., 2016, Judge et al., 2004, Kelloway, 2015, Li & Bagger, 2011, Oswald, 1996).

Practical Implications

Our study also suggests a number of practical implications for individuals and managers. Our findings demonstrate the importance of FSSBs as a mechanism to translate the impact of the organizational context on the subordinates’ outcomes. Given that FSSBs is relatively a new construct (Hammer et al., 2009), supervisors may not be aware of and trained in delivering FSSBs to their subordinates. Developing FSSB skills and tracking their effectiveness may be a fundamental training intervention approach for managers (Hammer et al., 2017). Furthermore, the training interventions may include a focus on elderly care responsibilities of the subordinates and understanding how the resources generated with FSSBs may actually help them to deal with their elderly care in more effective ways.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage.

Allen, T. D. (2001). Family-supportive work environments: The role of organizational perceptions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58(3), 414–435. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2000.1774.

Annavarjula, M., & Das, D. (2013). Toward a fine balance: Cross-cultural comparison of work–family identities. Journal of Asia-Pacific Business, 14(1), 40–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/10599231.2013.732406.

Aryee, S., & Luk, V. (1996). Balancing two major parts of adult life experience: Work and family identity among dual-earner couples. Human Relations, 49(4), 465–487. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679604900404.

Aryee, S., Walumbwa, F. O., Gachunga, H., & Hartnell, C. A. (2016). Workplace family resources and service performance: The mediating role of work engagement. African Journal of Management, 2(2), 138–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322373.2016.1175265.

Bagger, J., & Li, A. (2014). How does supervisory family support influence employees' attitudes and behaviors? A social exchange perspective. Journal of Management, 40(4), 1123–1150. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311413922.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2009). The crossover of work engagement between working couples: A closer look at the role of empathy. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 24, 220–236.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2014). Job demands-resources theory. In P. Y. Chen & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Work and wellbeing: Wellbeing: A complete reference guide (Vol. III, pp. 37–64). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands-resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22, 273–285.

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Euwema, M. C. (2005). Job resources buffer the impact of job demands on burnout. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10(2), 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.10.2.170.

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Taris, T. W. (2003). A multigroup analysis of the job demands-resources model in four home care organizations. International Journal of Stress Management, 10(1), 16–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.10.1.16.

Bakker, A. B., & Sanz-Vergel, A. I. (2013). Weekly work engagement and flourishing: The role of hindrance and challenge job demands. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83, 397–409.

Bakker, A. B., Ten Brummelhuis, L. L., Prins, J. T., & van der Heijden, F. M. M. A. (2011). Applying the job demands–resources model to the work–home interface: A study among medical residents and their partners. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(1), 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.12.004.

Bakker, A. B., Westman, M., & Van Emmerik, I. J. H. (2009). Advancements in crossover theory. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 24, 206–219.

Batson, C. D., & Shaw, L. L. (1991). Evidence for altruism: Toward a pluralism of prosocial motives. Psychological Inquiry, 2, 107–122.

Bauer, D. J., Preacher, K. J., & Gil, K. M. (2006). Conceptualizing and testing random indirect effects and moderated mediation in multilevel models: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 11(2), 142–163.

Behson, S. J. (2002). Which dominates? The relative importance of work–family organizational support and general organizational context on employee outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(1), 53–72. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1845.

Bhave, D. P., Kramer, A., & Glomb, T. M. (2010). Work–family conflict in work groups: Social information processing, support, and demo- graphic dissimilarity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95, 145–158. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017885.

Bond, J. T., Galinsky, E., Kim, S. S., & Brownfield, E. (2006). 2005 national study of employers. New York: Families and Work Institute.

Burch, K. A., Dugan, A. G., & Barnes-Farrell, J. (2018). Understanding what eldercare means for employees and organizations: A review and recommendations for future research. Work, Aging and Retirement, 5, 44–72. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/way011.

Calvano, L., & Dixon, J. (2015). Elderly care and work. In N. A. Pachana (Ed.), Encyclopedia of geropsychology. Singapore: Business Media Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-080-3_283-1.

Cameron, K. S., & Caza, A. (2004). Contributions to the discipline of positive organizational scholarship. American Behavioral Scientist, 47(6), 731–739. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764203260207.

Carmeli, E. (2014). The invisibles: Unpaid caregivers of the elderly. Frontiers in Public Health, 2(9), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2014.00091.

Casper, W. J., Fox, K. E., Sitzmann, T. M., & Landy, A. L. (2004). Supervisor referrals to work–family programs. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 9(2), 136–151.

Cavanaugh, M. A., Boswell, W. R., Roehling, M. V., & Boudreau, J. W. (2000). An empirical examination of self-reported work stress among U.S. managers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.1.65.

Chen, Y.-P., Shaffer, M., Westman, M., Chen, S., Lazarova, M., & Reiche, S. (2014). Family role performance: Scale development and validation. Applied Psychology. An International Review, 63, 190–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12005.

Crain, T. L., & Stevens, S. C. (2018). Family-supportive supervisor behaviors: A review and recommendations for research and practice. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(7), 869–888.

Crawford, E. R., LePine, J. A., & Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta–analytic test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95, 834–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019364.

Crimmins, E. M., & Beltran-Sanchez, H. (2011). Mortality and morbidity trends: Is there compression of morbidity? The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66(1), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbq088.

Cunny, K. A., & Perri, M. (1991). Single-item vs multiple-item measures of health-related quality of life. Psychological Reports, 69, 127–131.

Dawson’s (2016). Retrieved on and avaiable at (2016): https://www.jeremydawson.co.uk/slopes.htm.

De Lange, A. H., Taris, T. W., Kompier, M. A. J., Houtman, I. L. D., & Bongers, P. M. (2003). The very best of the Millennium’: Longitudinal research and the Demand-Control-(Support) Model. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 8, 282/305.

De Salvo, K. B., Fisher, W. P., Tran, K., Bloser, N., Merrill, W., & Peabody, J. (2006). Assessing measurement properties of two single-item general health measures. Quality of Life Research, 15(2), 191–201.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., & De Jonge, J. (2001). Burnout and engagement at work as a function of demands and control. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 27(4), 279–286. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.615.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.86.3.499.

Du, D., Derks, D., Bakker, A. B., & Lu, C. (2018). Does homesickness undermine the potential of job resources? A perspective from the work–home resources model. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39, 96–112. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2212.

Dupré, K. E., & Day, A. L. (2007). The effects of supportive management and job quality on the turnover intentions and health of military personnel. Human Resource Management, 46(2), 185–201. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20156.

Duxbury, L., Higgins, C., & Smart, R. (2011). Elder care and the impact of caregiver strain on the health of employed caregivers. Works, 40(1), 29–40.

Eby, L. T., Casper, W. J., Lockwood, A., Bordeaux, C., & Brinley, A. (2005). Work and family research in IO/OB: Content analysis and review of the literature (1980–2002). Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66(1), 124–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2003.11.003.

Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 500–507. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.71.3.500.

Eisenberger, R., Stinglhamber, F., Vandenberghe, C., Sucharski, I. L., & Rhoades, L. (2002). Perceived supervisor support: Contributions to perceived organizational support and employee retention. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(3), 565–573. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.565.

Eisenberger, R., Karagonlar, G., Stinglhamber, F., Neves, P., Becker, T. E., Gonzalez-Morales, M. G., & Steiger-Mueller, M. (2009). Leader-member exchange and affective organizational commitment: The contribution of supervisor’s organizational embodiment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95, 1085–1103.

Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Cooper, M. L. (2011). Relation of work-family conflict to health outcomes: A four-year longitudinal study of employed parents. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 70(4), 325–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1997.tb00652.x.

Gillespie, J. Z., Barger, P. B., Yugo, J. E., Conley, C. J., & Ritter, L. (2011). The suppression of negative emotions in elder care. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 26, 566–583. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941111164481.

Goh, J., Pfeffer, J., Zenios, S. A., & Rajpal, S. (2015). Workplace stressors & health outcomes: Health policy for the workplace. Behavioral Science & Policy, 1(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1353/bsp.2015.0001.

Grawitch, M. J., Gottschalk, M., & Munz, D. C. (2006). The path to a healthy workplace: A critical review linking healthy workplace practices, employee well-being, and organizational improvements. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 58(3), 129–147. https://doi.org/10.1037/1065-9293.58.3.129.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Kossek, E. E. (2014). The contemporary career: A work–home perspective. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1, 361–388. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091324.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Powell, G. N. (2006). When work and family are allies: A theory of work family enrichment. Academy of Management Review, 31, 72–92. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2006.19379625.

Greenhaus, J. H., Ziegert, J. C., & Allen, T. D. (2012). When family-supportive supervision matters: Relations between multiple sources of support and work–family balance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80, 266–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.10.008.

Hall, G. B., Dollard, M. F., Winefield, A. H., Dormann, C., & Bakker, A. B. (2013). Psychosocial safety climate buffers effects of job demands on depression and positive organizational behaviors. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 26, 355–377.

Hammer, L. B., Johnson, R. C., Crain, T. L., Bodner, T., Kossek, E. E., Kelly, D., Kelly, E. L., Buxton, O. M., Karuntzos, G., Chosewood, L. C., & Berkman, L. (2015). Intervention effects on safety compliance and citizenship behaviors: Evidence from the work, family, and health study. Journal of Applied Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000047.

Hammer, L. B., Kossek, E. E., Anger, W. K., Bodner, T. E., & Zimmerman, K. L. (2011). Clarifying work–family intervention processes: The roles of work–family conflict and family-supportive supervisor behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(1), 134–150. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020927.

Hammer, L. B., Kossek, E. E., Bodner, T. E., & Crain, T. (2013). Measurement development and validation of the Family Supportive Supervisor Behavior Short-Form (FSSB-SF). Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18(3), 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032612.

Hammer, L. B., Kossek, E. E., Yragui, N. L., Bodner, T. E., & Hanson, G. C. (2009). Development and validation of a multidimensional measure of Family Supportive Supervisor Behaviors (FSSB). Journal of Management, 35, 837–856.

Hammer, L. B., Kossek, E. E., Zimmerman, K. L., & Daniels, R. (2007). Clarifying the construct of family-supportive supervisory behaviors (FSSB): A multilevel perspective. In P. L. Perrewé & D. C. Ganster (Eds.), Research in occupational stress and well-being (Vol. 6, pp. 171–211). Amsterdam: Emerald (MCB UP. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1479-3555(06)06005-7.

Hammer, L. B., Wan, W. H., Brockwood, K. J., Mohr, C. D., & Carlson, K. F. (2017). Military, work, and health characteristics of veterans and reservists from the Study for Employment Retention of Veterans (SERVe). Military Psychology, 29, 491–512.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (1st ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

Hill, R. T., Matthews, R. A., & Walsh, B. M. (2016). The emergence of family-specific support constructs: Cross-level effects of family-supportive supervision and family-supportive organization perceptions on individual outcomes. Stress and Health, 32(5), 472–484. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2643.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6(4), 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.6.4.307.

Hobfoll, S. E., Johnson, R. J., Ennis, N., & Jackson, A. P. (2003). Resource loss, resource gain, and emotional outcomes among inner city women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(3), 632–643. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.84.3.632.

Hox, J. (2002). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55.

Idler, E. L., & Benyamini, Y. (1997). Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38, 21–37. https://doi.org/10.2307/2955359.

James, I., Andershed, B., & Ternestedt, B. M. (2009). The encounter between informal and professional care at the end of life. Qualitative Health Research, 19, 258–271.

Jones, K. P., King, E. B., Gilrane, V. L., McCausland, T. C., Cortina, J. M., & Grimm, K. J. (2016). The baby bump: Managing a dynamic stigma over time. Journal of Management, 42(6), 1530–1556. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313503012.

Judge, T. A., Van Vianen, A. E. M., & De Pater, I. (2004). Emotional stability, core self-evaluations, and job outcomes: A review of the evidence and an agenda for future research. Human Performance, 17, 325–346.

Kelloway, E. K. (2015). The psychologically healthy workplace. Stress and Health, 31(4), 263–263. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2656.

Kidder, D. L., & McLean Parks, J. (2001). The good soldier: Who is s(he)? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(8), 939–959. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.119.

Kim, N., & Gordon, J. R. (2014). Addressing the stress of work and elder caregiving of the graying workforce: The moderating effects of financial strain on the relationship between work-caregiving conflict and psycho- logical well-being. Human Resource Management, 53, 723–747. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21582.

Koch, A. R., & Binnewies, C. (2015). Setting a good example: Supervisors as work-life-friendly role models within the context of boundary management. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(1), 82–92. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037890.

Kossek, E. E., Colquitt, J. A., & Noe, R. A. (2001). Caregiving decisions, well-being, and performance: The effects of place and provider as a function of dependent type and work-family climates. Academy of Management Journal, 44(1), 29–44. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069335.

Kossek, E. E., Pichler, S., Bodner, T. E., & Hammer, L. B. (2011). Workplace social support and work-family conflict: A meta-analysis clarifying the influence of general and work-family specific supervisor and organizational support. Personnel Psychology, 64(2), 289–313. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01211.x.

Kossek, E. E., Thompson, R. J., Lawson, K. M., Bodner, T., Perrigino, M. B., Hammer, L. B., Buxton, O. M., Almeida, D. M., Moen, P., Hurtado, D. A., Wipfli, B., Berkman, L. F., & Bray, J. W. (2017). Caring for the elderly at work and home: Can a randomized organizational intervention improve psychological health? Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 24 (1):36-54.https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000104.

Lapierre, L. M., & Allen, T. D. (2006). Work-supportive family, family-supportive supervision, use of organizational benefits, and problem-focused coping: Implications for work-family conflict and employee well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 11(2), 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.11.2.169.

Las Heras, M., Rofcanin, Y., Bal, M. B., & Stollberger, J. (2017). How do flexibility i-deals relate to work performance? Exploring the roles of family performance and organizational context. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 38, 1280–1294. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2203.

Las Heras, M., Trefalt, S., & Escribano, P. I. (2015). How national context moderates the impact of family-supportive supervisory behavior on job performance and turnover intentions. The Journal of the Iberoamerican Academy of Management, 13, 55–82.

Li, A., & Bagger, J. (2011). Walking in your shoes: Interactive effects of child care responsibility difference and gender similarity on supervisory family support and work-related outcomes. Group & Organization Management, 36(6), 659–691.

Maitlis, S. (2005). The social processes of organizational sense-making. Academy of Management Journal, 48, 21–49. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2005.15993111.

Marinova, S. V., Moon, H. K., & Van Dyne, L. (2010). Are all good soldier behaviors the same? Supporting multidimensionality of organizational citizenship behaviors based on rewards and roles. Human Relations, 63(10), 1463–1485. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709359432.

Matthews, R. A., Mills, M. J., Trout, R. C., & English, L. (2014). Family-supportive supervisor behaviors, work engagement, and subjective well-being: A contextually dependent mediated process. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 19(2), 168–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036012.