Abstract

This systematic review and meta-analysis aims to evaluate the effectiveness of internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy (ICBT) on anxiety and depression among persons with chronic health conditions. A systematic database search was conducted of MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycInfo, EMBASE, and Cochrane for relevant studies published from 1990 to September 2018. A study was included if the following criteria were met: (1) randomized controlled trial involving an ICBT intervention; (2) participants experienced a chronic health condition; (3) participants ≥ 18 years of age; and (4) effects of ICBT on anxiety and/or depression were reported. The Cochrane Risk of Bias tool was used to assess the risk of bias on the included studies. Pooled analysis was conducted on the primary and condition specific secondary outcomes. Twenty-five studies met inclusion criteria and investigated the following chronic health conditions: tinnitus (n = 6), fibromyalgia (n = 3), pain (n = 7), rheumatoid arthritis (n = 3), cardiovascular disease (n = 2), diabetes (n = 1), cancer (n = 1), heterogeneous chronic disease population (n = 1), and spinal cord injury (n = 1). Pooled analysis demonstrated small effects of ICBT in improving anxiety and depression. Moderate effects of therapist-guided approach were seen for depression and anxiety outcomes; while, self-guided approaches resulted in small effects for depression and moderate effects in anxiety outcomes. ICBT shows promise as an alternative to traditional face-to-face interventions among persons with chronic health conditions. Future research on long-term effects of ICBT for individuals with chronic health conditions is needed.

Trial Registration PROSPERO registration number: CRD42018087292.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is growing interest in the use of internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy (ICBT) as an alternative to face-to-face cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) (Andersson & Titov, 2014). In ICBT, patients have access to online treatment materials that are based on CBT self-help manuals and designed to provide the same information that is provided in face-to-face CBT (e.g., psychoeducation on the cognitive behavioural model, cognitive restructuring, behavioural skills, relapse prevention). In addition to core treatment materials, ICBT can also include supplementary materials related to common problems such as sleep disturbances, and thus can also address comorbidities during treatment. As reviewed by Andersson (2016), the nature of the ICBT materials varies in the research literature, but often includes text and images and sometimes audiovisual content. Lessons are typically delivered weekly and are followed by homework assignments. Treatment duration in ICBT is similar to face-to-face CBT, with patients partaking in the program for a duration of 5–15 weeks (Andersson, 2016).

ICBT overcomes several barriers associated with face-to-face CBT, such as geography, limited mobility or time constraints, and the stigma patients experience related to seeking psychological treatments (Andersson & Titov, 2014). The online format of ICBT enables patients to access lessons in a time and location that best suits their schedule, and may foster self-efficacy in patients who complete the programs (Andersson, 2016). Additionally, ICBT reduces therapist burden, as on average, therapists spend between 15 and 20 min per week supporting each patient (Andersson et al., 2013).

ICBT can either be self-guided or therapist-guided. In self-guided ICBT, participants do not have regular contact with a therapist. In contrast, therapist-guided ICBT programs usually involve weekly contact with an online therapist or guide, either through asynchronous online messaging or by telephone. Some studies have found that there is no difference in the efficacy of therapist-guided or self-guided ICBT programs for depression (Titov et al., 2015), social anxiety (Dear et al., 2016), and panic disorder (Fogliati et al., 2016). It has been hypothesized that self-guided programs result in strong outcomes when they involve pre-screening, and include well-developed engaging materials and automated emails and contact information for a therapist if this is required (Dear et al., 2016).

In general, there is growing evidence supporting the use of ICBT for a variety of mental health conditions (Andersson et al., 2014). A review of 30 studies found that therapist-guided ICBT is an effective treatment for anxiety disorders, with large effect sizes (Olthuis et al., 2015). Similar effects have been found in studies comparing ICBT to face-to-face CBT for mild and moderate depression, although more research is required to identify if ICBT is suitable for more severe cases of depression (Andersson, 2016). Adherence rates are similar in guided ICBT (80.8%) and face-to-face treatments (83.9%) for depression when there is a clear deadline for when treatment will end (e.g., 8 weeks), as opposed to when patients have no clear deadline and ongoing access to treatment materials (van Ballegooijen et al., 2014).

In addition to the above research, there is growing literature on the use of ICBT for chronic health conditions as these conditions are often comorbid with depression and anxiety (van Beugen et al., 2014). Several reviews have previously examined the effect of internet-based psychological interventions in improving outcomes among those with chronic health conditions (Beatty & Lambert, 2013; Cuijpers et al., 2008; van Beugen et al., 2014). When targeting anxiety and depression outcomes among those with chronic illness, improvement has also been found on secondary outcomes such as disability (Jasper et al., 2014; Kaldo et al., 2008; Vallejo et al., 2015), pain severity (Buhrman et al., 2004; Chiauzzi et al., 2010; Dear et al., 2013, 2015), and fatigue (Friesen et al., 2017; Williams et al., 2010).

Since these reviews were completed, there has been additional research on ICBT for chronic health conditions, including research on some additional chronic health conditions such as fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, and spinal cord injury. Furthermore, there remains a gap in the literature on ICBT for chronic conditions examining the efficacy of ICBT compared to various control groups. Finally, the effect of self-guided versus therapist-guided approaches on outcomes has yet to be determined in a review. Thus, the purpose of the current paper was to conduct an updated systematic review and meta-analysis on ICBT for chronic health conditions. This study differs from previous reviews by examining: the effects of self-guided compared to therapist-guided ICBT on both anxiety and depression outcomes; how ICBT compares to different comparator groups beyond waiting-list comparison (e.g., attention control, online discussion, treatment as usual); the effect of ICBT on condition specific secondary outcomes; and existing gaps in research in terms of methodological quality to provide direction for future research.

Methods

Literature search strategy

The systematic review and meta-analysis followed guidelines of the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; Liberati et al., 2009). A literature search was conducted to locate the studies published from 1990 to September 2018 from several databases, including MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycInfo, EMBASE, and Cochrane. Keywords used in the literature search to retrieve articles included: online, cognitive behavioural therapy, chronic disease. In addition to the keywords originally listed in the PROSPERO trial registration, specific keywords related to chronic health conditions were also searched. “Appendix” provides a list of specific keywords and exact search strategies. Reference lists of the included articles were also scanned to identify additional articles missed in the original literature search.

Study selection

Articles were reviewed by 2 independent reviewers (S.M. and V.P.) and were included if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) randomized controlled trial (RCT) involving an ICBT intervention; (2) had a study sample with a chronic health condition (i.e., duration ≥ 3 months); (3) included participants ≥ 18 years of age; and (4) reported the effects of the ICBT intervention on anxiety and/or depression. Only those articles available in English were retrieved. Articles without sufficient reporting detail to enable pooling of data were excluded (e.g., studies that did not provided means or medians for their outcomes). Before excluding articles for insufficient data, corresponding authors were contacted. Studies that only provided specific modules of CBT such as relaxation training or psychoeducation were excluded. Studies were also excluded if ICBT only targeted physical health-related outcomes such as physical activity or nutritional wellness. Articles were excluded if they were review studies or case studies. A third independent reviewer (H.H.) resolved any disagreements about article inclusion.

Study appraisal and data analysis

Two independent reviewers (S.M. and V.P.) extracted the following data from each of the selected articles: author, year, sample size, population, country, health condition, time since diagnosis, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, study design, comparator, type of contact with therapist, automated emails, intervention duration, time points of measures, primary outcomes (anxiety and depression), secondary condition specific outcomes (e.g., fatigue, disability, pain), dropout rates (defined as those that did not complete the full program), concomitant treatments, and adverse effects. To assess the risk of bias on the included studies, two independent reviewers (S.M. and V.P.) used the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (Higgins et al., 2011). The tool includes criteria for random sequence generation, allocation concealment, selective reporting, other bias, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, and incomplete outcome data (i.e., not reporting on the primary outcomes post treatment). Thresholds for bias including incomplete outcome data were based on the Cochrane guidelines. The Cochrane Risk of Bias tool has thresholds for good, fair, and poor quality studies.

Pooled analysis was conducted on the primary outcomes: depression and anxiety. A sub-analysis was conducted on secondary condition specific outcomes. Cohen’s d was used to calculate standard difference in means (SDM) (± SE) for outcomes using the software package Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (version 3). Effect sizes were interpreted as small > 0.2; moderate > 0.5; and large > 0.8 (Cohen, 1988). Heterogeneity between studies was examined using the I2 statistic. A threshold of an I2 statistic of greater than 50% was used to identify significant heterogeneity based on Cochrane guidelines. Random effects model was used when threshold was met and a fixed effects model was used threshold was not reached.

Results

Study selection and background

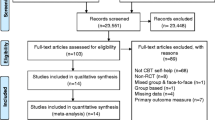

Of the 456 studies reviewed, 25 met inclusion criteria. Figure 1 provides a PRISMA Flow Diagram of the study selection process. The included studies consisted of ICBT interventions in various populations including: pain (n = 7; Buhrman et al., 2011, 2004; Carpenter et al., 2012; Chiauzzi et al., 2010; Dear et al., 2013, 2015; Peters et al., 2017); tinnitus (n = 6; Abbott et al., 2009; Andersson et al., 2002; Hesser et al., 2012; Jasper et al., 2014; Kaldo et al., 2008; Weise et al., 2016); fibromyalgia (n = 3; Friesen et al., 2017; Vallejo et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2010); rheumatoid arthritis (RA; n = 3; Ferwerda et al., 2017; Shigaki et al., 2013; Trudeau et al., 2015); cardiovascular disease (n = 2; Glozier et al., 2013; Lundgren et al., 2016); diabetes (n = 1; Newby et al., 2017); cancer (n = 1; Compen et al., 2018); spinal cord injury (SCI; n = 1; Migliorini et al., 2016), and heterogeneous chronic disease population (n = 1; Wilson et al., 2018). The sample size ranged from 27 to 562 with the pooled number of participants being 3450. Specific participant and study characteristics are provided in Table 1. ICBT was provided through a self-directed approach in seven studies (Carpenter et al., 2012; Chiauzzi et al., 2010; Glozier et al., 2013; Migliorini et al., 2016; Trudeau et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2010; Wilson et al., 2018) and therapist-guided approach which involved weekly or biweekly contact in 18 studies (Abbott et al., 2009; Andersson et al., 2002; Buhrman et al., 2004, 2011; Compen et al., 2018; Dear et al., 2013, 2015; Ferwerda et al., 2017; Friesen et al., 2017; Hesser et al., 2012; Jasper et al., 2014; Kaldo et al., 2008; Lundgren et al., 2016; Newby et al., 2017; Peters et al., 2017; Shigaki et al., 2013; Vallejo et al., 2015; Weise et al., 2016). The studies compared ICBT to waiting-list control (n = 13; Andersson et al., 2002; Buhrman et al., 2004, 2011; Carpenter et al., 2012; Dear et al., 2013, 2015; Friesen et al., 2017; Migliorini et al., 2016; Newby et al., 2017; Peters et al., 2017; Shigaki et al., 2013; Trudeau et al., 2015; Vallejo et al., 2015), face-to-face group CBT (n = 4; Compen et al., 2018; Ferwerda et al., 2017; Jasper et al., 2014; Kaldo et al., 2008; Vallejo et al., 2015), online discussion forum (n = 4; Hesser et al., 2012; Jasper et al., 2014; Lundgren et al.,2016; Weise et al., 2016), treatment as usual (TAU) (n = 2; Compen et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2010), information only (n = 2; Abbott et al., 2009; Chiauzzi et al., 2010), attention control (n = 1; Glozier et al., 2013), positive psychology intervention (n = 1; Peters et al., 2017), and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) (n = 1; Hesser et al., 2012). Duration of treatment among the studies ranged from 3 to 65 weeks. Study drop-out rates, or those that did not complete the entire ICBT program, ranged from 5 to 38% among therapist-guided approaches and 19–34% among self-guided approaches.

Assessment of study risk of bias

Figure 2 provides risk of bias among the RCTs. Of the included studies, only one was classified as “good” quality as it was the only study that met criteria for blinding of participants and personnel in addition to the other criteria assessed by the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (Glozier et al., 2013). Nineteen studies were rated as fair quality (Andersson et al., 2002; Buhrman et al., 2011; Carpenter et al., 2012; Chiauzzi et al. 2010; Compen et al., 2018; Dear et al., 2015; Ferwerda et al., 2017; Friesen et al., 2017; Hesser et al., 2012; Lundgren et al., 2016; Jasper et al., 2014; Migliorini et al., 2016; Newby et al., 2017; Peters et al., 2017; Trudeau et al., 2015; Vallejo et al., 2015; Weise et al., 2016; Williams et al., 2010; Wilson et al., 2018), and five studies were rated as being of poor quality (Abbott et al., 2009; Buhrman et al., 2004; Dear et al., 2013; Kaldo et al., 2008; Shigaki et al., 2013).

Efficacy of ICBT

Overall

Significant heterogeneity was evident for the primary outcomes of anxiety (I2= 81.2%, p < .01) and depression (I2= 68.8%, p < .01); therefore, a random-effects model was used. Pooled analysis demonstrated small effects of ICBT in improving overall anxiety (SDM = 0.45 ± 0.09, p < .001) and overall depression (SDM = 0.31 ± 0.04, p < .001) (Figs. 3, 4) at post-treatment. A sensitivity analysis was conducted in order to confirm that the poor-quality studies were not overinflating or underinflating the effect size. Exclusion of these studies resulted in similar small effects of ICBT on anxiety (SDM = 0.46 ± 0.05, p < .001) and depression (SDM = 0.49 ± 0.04, p < .001) overall. Moderate effects of ICBT were found at 3-month follow up for anxiety (SDM = 0.51 ± 0.03, p < .001; Buhrman et al., 2004; Chiauzzi et al., 2010; Dear et al., 2013, 2015; Ferwerda et al., 2017; Trudeau et al., 2015) and depression (SDM = 0.66 ± 0.08, p < .001; Buhrman et al., 2004; Chiauzzi et al., 2010; Dear et al., 2013, 2015; Ferwerda et al., 2017; Trudeau et al., 2015; Vallejo et al., 2015) outcomes. At 6-month follow up, large effects were seen for anxiety (SDM = 1.69 ± 0.10, p < .001; Chiauzzi et al., 2010; Ferwerda et al., 2017; Trudeau et al., 2015) and depression (SDM = 1.71 ± 0.14, p < .001; Chiauzzi et al., 2010; Ferwerda et al., 2017; Trudeau et al., 2015; Vallejo et al., 2015).

Small to moderate effects of ICBT were seen on anxiety outcomes when compared to attentional control (SDM = 0.22 ± 0.08, p = .008; Glozier et al., 2013), online discussion (SDM = 0.59 ± 0.12, p < .001; Hesser et al., 2012; Jasper et al., 2014; Weise et al., 2016), TAU (SDM = 0.63 ± 0.22, p = .005; Ferwerda et al., 2017; Newby et al., 2017), and waiting-list control (SDM = 0.55 ± 0.07, p < .001; Andersson et al., 2002; Friesen et al., 2017; Buhrman et al., 2004, 2011; Dear et al., 2013, 2015; Migliorini et al., 2016; Peters et al., 2017; Trudeau et al., 2015) groups. No significant difference was seen among ICBT and ACT (SDM = 0.11 ± 0.25, p = .66; Hesser et al., 2012), face-to-face group CBT (SDM = 0.04 ± 0.17, p = .83; Jasper et al., 2014; Kaldo et al., 2008), PPI (SDM = 0.0.8 ± 0.13, p = .56; Peters et al., 2017), or information control (SDM = 0.96 ± 0.90, p = .29; Abbott et al., 2009; Chiauzzi et al., 2010). Similarly, ICBT was found to have small to moderate effects on depression outcomes when compared to attentional control (SDM = 0.22 ± 0.08, p = .007; Glozier et al., 2013; Wilson et al., 2018), online discussion (SDM = 0.40 ± 0.11p < .001; Hesser et al., 2012; Jasper et al., 2014; Lundgren et al., 2016; Weise et al., 2016), TAU (SDM = 0.57 ± 0.22, p = .008; Compen et al., 2018; Ferwerda et al., 2017; Newby et al., 2017; Williams et al., 2010), and waiting-list control (SDM = 0.60 ± 0.12, p < .001; Andersson et al., 2002; Buhrman et al., 2004, 2011; Dear et al., 2013, 2015; Friesen et al., 2017; Migliorini et al., 2016; Peters et al., 2017; Shigaki et al., 2013; Trudeau et al., 2015; Vallejo et al., 2015) groups. No significant difference was seen among ICBT and ACT (SDM = 0.25 ± 0.25, p = .32; Hesser et al., 2012), face-to-face group CBT (SDM = 0.18 ± 0.11, p = .10; Compen et al., 2018; Jasper et al., 2014; Kaldo et al., 2008; Vallejo et al., 2015), PPI (SDM = 0.07 ± 0.13, p = .61; Peters et al., 2017), or information control (SDM = 0.49 ± 0.41, p = .23; Abbott et al., 2009; Chiauzzi et al., 2010).

Pooled analysis of studies comparing self-guided and therapist-guided found a moderate effect size in overall efficacy of self-guided (SDM = 0.57 ± 0.12, p < .001) and therapist-guided (SDM = 0.54 ± 0.08, p < .001) on anxiety symptoms compared to waiting-list control groups. Pooled studies examining depression outcomes found moderate effects of therapist-guided approach (SDM = 0.64 ± 0.15, p < .001), while a small effect was seen in self-guided (SDM = 0.45 ± 0.18, p < .01). Pooled analysis comparing studies that provided telephone only compared to email only support found moderate effects of both on anxiety (SDM = 0.41 ± 0.19, p < .03 vs. SDM = 0.31 ± 0.10, p < .01) and depression (SDM = 0.35 ± 0.07, p < .001 vs. SDM = 0.36 ± 0.08, p < .001) outcomes.

Pain

The pooled sub-analysis of the pain population (n = 950) demonstrated moderate effects in anxiety (SDM = 0.64 ± 0.249, p = .01; Buhrman et al., 2004, 2011; Chiauzzi et al., 2010; Dear et al., 2013, 2015; Peters et al., 2017), depression (SDM = 0.64 ± 0.16, p = .001; Buhrman et al., 2004, 2011; Chiauzzi et al., 2010; Dear et al., 2013, 2015; Peters et al., 2017), and pain severity (SDM = 0.41 ± 0.14, p = .003; Buhrman et al., 2004, 2011; Chiauzzi et al., 2010; Dear et al., 2013, 2015; Peters et al., 2017). Small effects of ICBT were seen on self-efficacy (SDM = 0.47 ± 0.15, p = .001; Carpenter et al., 2012; Chiauzzi et al., 2010; Dear et al., 2013, 2015). No significant effects were seen on catastrophizing (SDM = 1.11 ± 0.58, p = .06; Chiauzzi et al., 2010; Dear et al., 2013; Peters et al., 2017).

Tinnitus

A pooled sub-analysis among those with tinnitus (n = 493) revealed small effects in anxiety (SDM = 0.31 ± 0.07, p < .001; Abbott et al., 2009; Andersson et al., 2002; Hesser et al., 2012; Jasper et al., 2014; Kaldo et al., 2008; Weise et al., 2016), depression (SDM = 0.28 ± 0.07p < .001) (Abbott et al., 2009; Andersson et al., 2002; Hesser et al., 2012; Jasper et al., 2014; Kaldo et al., 2008; Weise et al., 2016), insomnia (SDM = 0.31 ± 0.09, p < .001; Hesser et al., 2012; Jasper et al., 2014; Kaldo et al., 2008; Weise et al., 2016), acceptance (SDM = 0.36 ± 0.10, p < .001; Hesser et al., 2012; Jasper et al., 2014; Weise et al., 2016), and disability (SDM = 0.48 ± 0.09, p < .001; Hesser et al., 2012; Jasper et al., 2014; Kaldo et al., 2008; Weise et al., 2016).

Fibromyalgia

Among those with fibromyalgia (n = 238), moderate effects were seen in anxiety (SDM = 0.57 ± 0.26, p = .03; Friesen et al., 2017), depression (SDM = 0.42 ± 0.13, p < .001; Friesen et al., 2017; Vallejo et al., 2015; Williams et al., 2010), catastrophizing (SDM = 0.59 ± 0.17, p < .001; Friesen et al., 2017; Vallejo et al., 2015), and pain severity (SDM = 0.51 ± 0.15, p < .001; Friesen et al., 2017; Williams et al., 2010). Small effect size was found in disability (SDM = 0.40 ± 0.17, p = .02; Friesen et al., 2017; Vallejo et al., 2015). No significant effect was seen in fatigue (SDM = 0.12 ± 0.15, p = .43; Friesen et al., 2017).

Rheumatoid arthritis

Pooled analysis among those with RA (n = 484) demonstrated moderate effects in anxiety (SDM was 0.53 ± 0.11, p < .001; Ferwerda et al., 2017; Trudeau et al., 2015) and small effects in depression (SDM = 0.44 ± 0.10, p < .001; Ferwerda et al., 2017; Shigaki et al., 2013; Trudeau et al., 2015) outcomes. No significant effect was seen on pain severity (SDM = 0.17 ± 0.11, p = .14) or self-efficacy (SDM = 2.01 ± 1.30, p = .12; Shigaki et al., 2013; Trudeau et al., 2015).

Cardiovascular disease

In the cardiovascular disease population, two RCTs evaluated the effectiveness of ICBT in improving anxiety and depression. The first, by Glozier et al. (2013), demonstrated small effects of self-guided ICBT (n = 562) on anxiety (SDM = 0.22 ± 0.08, p = .008) and depression (SDM = 0.20 ± 0.08, p = .02) compared to an attention control. The second, by Lundgren et al. (2016), found no significant effect of therapist guided ICBT on depression (SDM = 0.31 ± 0.29, p = .27) compared to an online discussion form.

Cancer

Among those with cancer, Compen et al. (2018) found no significant effects of therapist-guided ICBT on depression (SDM = 0.19 ± 0.17, p = .26) compared to face to face group Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) control. However, large effects were seen compared to TAU on depression (SDM = 0.74 ± 0.17, p < .001).

Diabetes

Newby et al. (2017)demonstrated large effects of therapist-guided ICBT (n = 91) on anxiety SDM = 0.86 ± 0.22, p < .001) and depression (SDM = 1.11 ± 0.23, p < .001) compared to TAU control.

Spinal cord injury

Among those with SCI, Migliorini et al. (2016) found no significant effects of self-guided ICBT (n = 30) on anxiety (SDM = 0.52 ± 0.29, p = .07) or depression (SDM = 0.17 ± 0.29, p = .55) compared to waiting-list control.

Heterogeneous chronic disease population

One RCT examined the efficacy of a transdiagnostic ICBT program among those from a variety of chronic illnesses including chronic pain, diabetes, cardiac, and respiratory disease (Wilson et al., 2018). The study found no significant effect of self-guided ICBT on depression (SDM = 0.42 ± 0.30, p = .15) compared to the attention control group who received weekly phone calls.

Discussion

The current meta-analysis evaluated the efficacy of ICBT on anxiety and depression among those with chronic health conditions including pain, tinnitus, fibromyalgia, RA, cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, spinal cord injury, and mixed chronic conditions. Pooled analysis of all 25 studies found that ICBT resulted in significant improvements in overall anxiety and depressive symptoms. Similar effect sizes were reported in previous systematic reviews on psychosocial outcomes among those with chronic health conditions (van Beugen et al., 2014; Cuijpers et al., 2008). The current study was the first to show improvements in secondary l outcomes including acceptance, catastrophizing, and self-efficacy. Small to moderate effects were seen among condition specific outcomes, including pain severity, disability, and insomnia.

The current study also added to the literature by comparing the effect sizes of self- and therapist-guided interventions on anxiety and depression outcomes. Therapist-guided ICBT resulted in moderate effects on depression outcomes; while only a small effect was seen on depression in self-guided ICBT approach. This is consistent with previous studies among individuals in the community with depression. Specifically, in a meta-analysis examining the efficacy of ICBT for adults with depression, Andersson and Cuijpers (2009) found a moderate effect of guided ICBT (d = 0.61) compared to a small effect in self-guided ICBT (d = 0.25).

The current study found that among those with chronic health conditions, self-guided interventions had similar effect sizes to therapist-guided interventions for anxiety symptoms. Several factors can account for the similar effects of ICBT between self- and therapist-guided interventions. Dear et al. (2016) reported that self-guided ICBT can be effective when participants are carefully screened for suitability and provided with automated messages to guide their progress. In the current review, both self-guided and therapist-guided studies screened participants to only include those that reported symptoms of distress, anxiety, or depression. Furthermore, in the current review, participants in most of the self-guided studies received automated messages as they progressed through the lessons. Additionally, several of the self-guided studies included reminder emails or telephone calls from the researcher if the participant did not log into the lesson. Hence, the current finding that the two types of guidance have similar effect sizes in improving anxiety symptoms may be attributed to the well-planned design of the self-guided interventions. Other studies have also found that self-guided approaches are effective when designed well to help the participant progress through the program (Titov et al., 2013, 2014).

Despite the similar effects on anxiety symptoms between self- and therapist-guided approaches, therapist-guided ICBT was found to have a greater effect on depression symptoms than self-guided ICBT. This may be explained by difference in adherence to intervention among the two groups. Previous evidence suggests those in the therapist-guided approaches have greater level of adherence to treatment protocols compared to those in self-guided interventions (Andersson et al., 2014; Andrews et al., 2016). Richards and Richardson (2012) found that levels of adherence among those with depression receiving self-guided interventions is around 26% and therapist-guided is at 72%. However, the current review found a small difference in self- and therapist-guided ICBT that did not complete the program (18% self-guided vs. 11% therapist-guided). It is possible that this small difference may account for the slight difference in effect size between the self- and therapist-guided approaches (d = 0.45 vs 0.59) in the current meta-analysis. The difference in dropout rates and adherence may indicate that individuals in the therapist-guided approaches may continue to remain in the course and continue to adhere to the treatment protocol resulting in more beneficial effects of the interventions. Thus, the differential effect of self-guided compared to therapist-guided approaches in depression outcomes could be explained by adherence related to therapist-guidance rather than factors such as greater insight or a supportive relationship.

Most studies in the current review used a waiting-list control group as a comparator. Not surprisingly, ICBT was significantly more effective in improving outcomes compared to waiting-list controls. Previous reviews have also reported on the benefit of ICBT over no treatment (van Beugen et al., 2014; Eccleston et al., 2014; Newby et al., 2016). The use of an inactive control group does not provide insight into potential confounding factors that may influence outcomes. That is, improvement in primary outcomes among waiting-list control studies could be due to the ICBT intervention or other factors such as increased activity or attention to condition. Pooled analysis from studies that provided participant social contact but not CBT-related content such as those with online discussion, TAU, and attention control groups as comparators provide evidence of small to moderate effects of ICBT on the primary outcomes. These results indicate that ICBT is more beneficial than social support or attention alone.

In the current meta-analysis, it was found that among studies which compared ICBT with active face-to-face control groups, including ACT and CBT, no significant differences in the primary outcomes were found. These findings are consistent with the meta-analysis by Andersson et al. (2014) which compared ICBT with face-to-face CBT. Furthermore, effects of ICBT seen in the current meta-analysis were comparable to those previously reported by meta-analysis of face-to-face CBT (Beltman et al., 2010; Hoffman et al., 2007). Evidence from the current study and those mentioned above indicate ICBT is equally as effective at improving psychosocial outcomes among those with chronic health conditions as face-to-face interventions.

Previous studies have reported on the acceptability of ICBT (Alberts et al., 2018; Newby et al., 2016; Soucy & Hadjistavropoulos, 2017), as well as on development of therapeutic alliance during ICBT (Alberts et al., 2018). Furthermore, ICBT may result in potential cost savings compared to traditional face-to-face interventions due to lower operating costs (Alaoui et al., 2017; Hedman et al., 2011). Future research on cost-effectiveness of ICBT among those with chronic health conditions may help to provide evidence for the adoption of ICBT in current rehabilitation settings in order to increase support for patients without added cost burden.

In addition to improvement in primary outcomes, the current study demonstrated improvement in some secondary outcomes including acceptance, catastrophizing, and self-efficacy. These secondary outcomes may be important mediators for maintenance and long-term self-management among participants with chronic health conditions. Hesser et al. (2014) found that acceptance was a mediator for therapeutic change among those with tinnitus participating in ICBT. Hence, it is important to examine the role of these secondary outcomes in long-term management of individuals with chronic health conditions. Exploration of interventions that target these outcomes may be warranted.

The current study had several limitations. First, condition-specific pooled analysis was sometimes based on relatively few or single studies which resulted in large confidence intervals. Second, most studies were of fair to poor quality indicating potential risk of bias in the outcomes assessed. Only one study blinded participants to treatment allocation. Though blinding is difficult among psychological trials, lack of blinding may introduce placebo effects. Third, when comparing ICBT against different interventions including face-to-face therapy, factors such as preference or satisfaction with intervention were not examined. Since these studies randomly allocated participants to receive ICBT or traditional face-to-face therapy, it could be argued that those who preferred face-to-face therapy were not satisfied with ICBT and did not make as large of an improvement as they would have if they received their preferred intervention. Fourth, level of engagement (e.g., completion of homework, log-ins, emails sent) with therapist was not reported in several studies, making it difficult to determine factors such as treatment engagement and optimal amount of support required to improve outcomes. Fifth, none of the studies compared ICBT to pharmacotherapy or reported on how ICBT impacted use of medication. Since the trials included participants with chronic health conditions, it is likely that many participants were prescribed drug treatments. Hence, in the future, it is important to examine the influence of pharmacotherapy on outcomes of interest. Sixth, some studies had to be excluded because they did not report information needed to be included in the analysis and the corresponding authors did not subsequently respond to emails requesting information. Lastly, most studies did not provide data on long-term follow-ups. Future studies should examine the effectiveness of ICBT among chronic health conditions over longer time periods including 1 year follow-up.

Despite these limitations, the findings from the current study provide important clinical implications for the use of ICBT among individuals with chronic conditions. First, ICBT is an effective approach for managing anxiety, depression, and secondary condition specific outcomes among those with chronic conditions. Second, adoption of ICBT provides increased access to mental health services for individuals with chronic health conditions that may be experiencing barriers to engaging in traditional services. Access to ICBT appears to provide individuals with chronic conditions with tools and skills required to maintain a better quality of life. Beyond delivering self-guided ICBT it would be interesting to examine the delivery of ICBT to individuals who have chronic conditions in ways that could potentially reduce operational costs and thus increase the number of clients who can be treated. For example, Hadjistavropoulos et al. (2017a, b) previously evaluated the effectiveness of ICBT with participants receiving weekly support from a designated therapist compared to a group which received ICBT only when patients initiated contacted with the therapist (optional support). This research suggests that optional therapist contact obtains positive outcomes, but substantially reduces therapist time to deliver guided-ICBT. Future studies could also examine the feasibility of ICBT delivered by a team rather than single provider; this has a scheduling advantage and may allow for increased access to guidance and lower operational costs.

An important area that still warrants research is adherence to Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines among behavioural trials (Boutron et al., 2017). The current study noted inadequate reporting of data in several domains including level of participant engagement and adherence to treatment protocol. Future trials should aim to adhere to reporting guidelines established by CONSORT in order to help standardize methodology and improve transparency. This lack of adherence to reporting guidelines can be an important barrier for evaluating the evidence and incorporating it into actionable recommendations in clinical practice guidelines (Boutron et al., 2017).

Future research should also examine preference-based trials that allow participants to select their preferred level of engagement and contact. The current study demonstrated that effect sizes were similar among those receiving telephone compared to email only support. However, future studies should record amount of time spent interacting with patients as well as quality of therapist-guidance in order to develop benchmarks for therapist contact (Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2018b). To date, there has been very little research on the nature of therapist-guidance that is provided to individuals who receive ICBT. Schneider et al. (2016) found that therapist behaviours such as task prompting and psychoeducation were correlated with lower symptom improvement during ICBT for depression. While the findings were correlational, the authors hypothesized that it was lower symptom improvement and patient engagement that prompted therapist behaviours. Overall, it is important to examine the role specific therapist behaviours may play on outcomes among patients with chronic health conditions.

Research which examines ICBT compared to traditional active treatments should evaluate patient satisfaction and therapist contact time between the groups. Studies that compare the effectiveness of ICBT with pharmacotherapy are still lacking. Future studies that examine the adjunct use of medication along with its comparative effect sizes are warranted. Additional clinical research is needed on the use of ICBT for specific chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, and spinal cord injury, as there continues to be limited research on ICBT for these patient groups. Furthermore, we require larger scale studies that would allow for examination of predictors or ICBT outcomes in those with chronic health conditions.

It is also interesting to note that all the ICBT studies currently evaluated were tailored to a specific chronic health condition. Only one study (Wilson et al., 2018) evaluated a transdiagnostic intervention to improve psychosocial outcomes amongst those with chronic health conditions. From an operational perspective, it would be desirable to treat many health conditions with a single chronic health conditions course rather than having single disease-specific ICBT programs. Future research should examine the effects of transdiagnostic chronic health conditions courses similar to how transdiagnostic programs are now being used to treat patients with symptoms of anxiety and or depression. Previous literature on transdiagnostic ICBT programs have found comparable results in improving psychosocial symptoms compared to disorder-specific ICBT (Dear et al., 2016; Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2016).

In conclusion, the current study adds to the body of evidence for the efficacy of ICBT in improving psychosocial and condition specific physical symptoms among those with chronic health conditions. Since most studies were conducted at a research setting, there is a potential for implementing ICBT in traditional outpatient and rehabilitation settings where access to trained mental health care workers is lacking (Hadjistavropoulos et al., 2018a). Furthermore, study of implementation facilitators and barriers would enhance understanding of how to best integrate ICBT in routine practice. Examination of long-term effects and satisfaction with treatment may be beneficial. Further research among specific chronic conditions is warranted.

References

Abbott, J. A. M., Kaldo, V., Klein, B., Austin, D., Hamilton, C., Piterman, L., et al. (2009). A cluster randomised trial of an internet-based intervention program for tinnitus distress in an industrial setting. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 38, 162–173.

Alaoui, S., Hedman-Lagerlöf, E., Ljótsson, B., & Lindefors, N. (2017). Does internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy reduce healthcare costs and resource use in treatment of social anxiety disorder? A cost-minimisation analysis conducted alongside a randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal Open, 7, e017053.

Alberts, N. M., Hadjistavropoulos, H. D., Titov, N., & Dear, B. F. (2018). Patient and provider perceptions of Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for recent cancer survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer, 26, 597–603.

Andersson, G. (2016). Internet-delivered psychological treatments. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 12, 157–179.

Andersson, G., Carlbring, P., Ljótsson, B., & Hedman, E. (2013). Guided Internet based CBT for common mental disorders. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 43, 223–233.

Andersson, G., & Cuijpers, P. (2009). Internet-based and other computerized psychological treatments for adult depression: A meta-analysis. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 38, 196–205.

Andersson, G., Cuijpers, P., Carlbring, P., Riper, H., & Hedman, E. (2014). Guided Internet based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry, 13, 288–295.

Andersson, G., Strömgren, T., Ström, L., & Lyttkens, L. (2002). Randomized controlled trial of internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for distress associated with tinnitus. Psychosomatic Medicine, 64, 810–816.

Andersson, G., & Titov, N. (2014). Advantages and limitations of internet-based treatments for common mental disorders. World Psychiatry, 13, 4–11.

Andrews, G., Hobbs, M. J., & Newby, J. M. (2016). Computerised cognitive behaviour therapy for major depression: A reply to the REEACT trial. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 19, 43.

Beatty, L., & Lambert, S. (2013). A systematic review of internet-based self-help therapeutic interventions to improve distress and disease-control among adults with chronic health conditions. Clinical Psychology Review, 33, 609–622.

Beltman, M. W., Voshaar, R. C. O., & Speckens, A. E. (2010). Cognitive-behavioural therapy for depression in people with a somatic disease: Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 197, 11–19.

Boutron, I., Altman, D. G., Moher, D., Schulz, K. F., & Ravaud, P. (2017). CONSORT statement for randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatments: A 2017 update and a CONSORT extension for nonpharmacologic trial abstracts. Annals of Internal Medicine, 167, 40–47.

Buhrman, M., Fältenhag, S., Ström, L., & Andersson, G. (2004). Controlled trial of Internet-based treatment with telephone support for chronic back pain. Pain, 111, 368–377.

Buhrman, M., Nilsson-Ihrfelt, E., Jannert, M., Ström, L., & Andersson, G. (2011). Guided internet-based cognitive behavioural treatment for chronic back pain reduces pain catastrophizing: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 43, 500–505.

Carpenter, K. M., Stoner, S. A., Mundt, J. M., & Stoelb, B. (2012). An online self-help CBT intervention for chronic lower back pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 28, 14.

Chiauzzi, E., Pujol, L. A., Wood, M., Bond, K., Black, R., Yiu, E., et al. (2010). painACTION-back pain: A self-management website for people with chronic back pain. Pain Medicine, 11, 1044–1058.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates.

Compen, F., Bisseling, E., Schellekens, M., Donders, R., Carlson, L., van der Lee, M., et al. (2018). Face-to-face and Internet-based mindfulness-based cognitive therapy compared with treatment as usual in reducing psychological distress in patients with cancer: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 36, 2413–2421.

Cuijpers, P., van Straten, A., & Andersson, G. (2008). Internet-administered cognitive behavior therapy for health problems: A systematic review. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 31, 169–177.

Dear, B. F., Gandy, M., Karin, E., Staples, L. G., Johnston, L., Fogliati, V. J., et al. (2015). The pain course: A randomised controlled trial examining an internet-delivered pain management program when provided with different levels of clinician support. Pain, 156, 1920.

Dear, B. F., Staples, L. G., Terides, M. D., Fogliati, V. J., Sheehan, J., Johnston, L., et al. (2016). Transdiagnostic versus disorder-specific and clinician-guided versus self-guided internet-delivered treatment for social anxiety disorder and comorbid disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 42, 30–44.

Dear, B. F., Titov, N., Perry, K. N., Johnston, L., Wootton, B. M., Terides, M. D., et al. (2013). The pain course: A randomised controlled trial of a clinician-guided Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy program for managing chronic pain and emotional well-being. Pain, 154, 942–950.

Eccleston, C., Fisher, E., Craig, L., Duggan, G. B., Rosser, B. A., & Keogh, E. (2014). Psychological therapies (Internet-delivered) for the management of chronic pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2, CD010152.

Ferwerda, M., van Beugen, S., van Middendorp, H., Spillekom-van Koulil, S., Donders, A. R. T., Visser, H., et al. (2017). A tailored-guided internet-based cognitive-behavioral intervention for patients with rheumatoid arthritis as an adjunct to standard rheumatological care: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Pain, 158, 868–878.

Fogliati, V. J., Dear, B. F., Staples, L. G., Terides, M. D., Sheehan, J., Johnston, L., et al. (2016). Disorder-specific versus transdiagnostic and clinician-guided versus self-guided internet-delivered treatment for panic disorder and comorbid disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 39, 88–102.

Friesen, L. N., Hadjistavropoulos, H. D., Schneider, L. H., Alberts, N. M., Titov, N., & Dear, B. F. (2017). Examination of an internet-delivered cognitive behavioural pain management course for adults with fibromyalgia: A randomized controlled trial. Pain, 158, 593–604.

Glozier, N., Christensen, H., Naismith, S., Cockayne, N., Donkin, L., Neal, B., et al. (2013). Internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy for adults with mild to moderate depression and high cardiovascular disease risks: A randomised attention-controlled trial. PLoS ONE, 8, e59139.

Hadjistavropoulos, H. D., Nugent, M., Alberts, N., Staples, L., Dear, B., & Titov, N. (2016). Transdiagnostic Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy in Canada: An open trial comparing results of a specialized online clinic and nonspecialized community clinics. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 42, 19–29.

Hadjistavropoulos, H. D., Nugent, M., Dirkse, D., & Pugh, N. (2017a). Implementation of Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy within community mental health clinics: A process evaluation using the consolidated framework for implementation research. BMC Psychiatry, 17, 331. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1496-7)

Hadjistavropoulos, H. D., Schneider, L. H., Edmonds, M., Karin, E., Nugent, M. N., Dirkse, D., et al. (2017b). Randomized controlled trial of Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy comparing standard weekly versus optional weekly therapist support. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 52, 15–24.

Hadjistavropoulos, H. D., Schneider, L. H., Hadjistavropoulos, T., Titov, N., & Dear, B. F. (2018a). Effectiveness, acceptability and feasibility of an Internet-delivered cognitive behavioral pain management program in a routine online therapy clinic in Canada. Canadian Journal of Pain, 2, 62–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/24740527.2018.1442675

Hadjistavropoulos, H. D., Schneider, L. H., Klassen, K., Dear, B. F., & Titov, N. (2018b). Development and evaluation of a scale assessing therapist fidelity to guidelines for delivering therapist-assisted Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2018.1457079

Hedman, E., Andersson, E., Ljótsson, B., Andersson, G., Rück, C., & Lindefors, N. (2011). Cost-effectiveness of Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy vs. cognitive behavioral group therapy for social anxiety disorder: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49, 729–736.

Hesser, H., Gustafsson, T., Lundén, C., Henrikson, O., Fattahi, K., Johnsson, E., et al. (2012). A randomized controlled trial of internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy in the treatment of tinnitus. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80, 649.

Hesser, H., Westin, V. Z., & Andersson, G. (2014). Acceptance as a mediator in internet-delivered acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive behavior therapy for tinnitus. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 37, 756–767.

Higgins, J. P., Altman, D. G., Gøtzsche, P. C., Jüni, P., Moher, D., Oxman, A. D., et al. (2011). The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ, 343, d5928.

Hoffman, B. M., Papas, R. K., Chatkoff, D. K., & Kerns, R. D. (2007). Meta-analysis of psychological interventions for chronic low back pain. Health Psychology, 26, 1.

Jasper, K., Weise, C., Conrad, I., Andersson, G., Hiller, W., & Kleinstaeuber, M. (2014). Internet-based guided self-help versus group cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic tinnitus: A randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 83, 234–246.

Kaldo, V., Levin, S., Widarsson, J., Buhrman, M., Larsen, H. C., & Andersson, G. (2008). Internet versus group cognitive-behavioral treatment of distress associated with tinnitus: A randomized controlled trial. Behavior Therapy, 39, 348–359.

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P., et al. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Medicine, 6, e1000100.

Lundgren, J. G., Dahlström, Ö., Andersson, G., Jaarsma, T., Köhler, A. K., & Johansson, P. (2016). The effect of guided web-based cognitive behavioral therapy on patients with depressive symptoms and heart failure: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18, e194.

Migliorini, C., Sinclair, A., Brown, D., Tonge, B., & New, P. (2016). A randomised control trial of an Internet-based cognitive behaviour treatment for mood disorder in adults with chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord, 54, 695.

Newby, J., Robins, L., Wilhelm, K., Smith, J., Fletcher, T., Gillis, I., et al. (2017). Web-based cognitive behavior therapy for depression in people with diabetes mellitus: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19, e157.

Newby, J. M., Twomey, C., Li, S. S. Y., & Andrews, G. (2016). Transdiagnostic computerised cognitive behavioural therapy for depression and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 199, 30–41.

Olthuis, J. V., Watt, M. C., Bailey, K., Hayden, J. A., & Stewart, S. H. (2015). Therapist-supported internet cognitive-behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in adults. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3, CD01156.

Peters, M. L., Smeets, E., Feijge, M., van Breukelen, G., Andersson, G., Buhrman, M., et al. (2017). Happy despite pain: A randomized controlled trial of an 8-week internet-delivered positive psychology intervention for enhancing well-being in patients with chronic pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 33, 962.

Richards, D., & Richardson, T. (2012). Computer-based psychological treatments for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 329–342.

Schneider, L. H., Hadjistavropoulos, H. D., & Faller, N. (2016). Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy for depressive symptoms: Therapist behaviours and their relationship to outcome and therapeutic alliance. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 44, 625–639.

Shigaki, C. L., Smarr, K. L., Siva, C., Ge, B., Musser, D., & Johnson, R. (2013). RAHelp: An online intervention for individuals with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care & Research, 65, 1573–1581.

Soucy, J. N., & Hadjistavropoulos, H. D. (2017). Treatment acceptability and preferences for managing severe health anxiety: Perceptions of internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy among primary care patients. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 57, 14–24.

Titov, N., Dear, B. F., Staples, L. G., Terides, M. D., Karin, E., Sheehan, J., et al. (2015). Disorder-specific versus transdiagnostic and clinician-guided versus self-guided treatment for major depressive disorder and comorbid anxiety disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 35, 88–102.

Trudeau, K. J., Pujol, L. A., DasMahapatra, P., Wall, R., Black, R. A., & Zacharoff, K. (2015). A randomized controlled trial of an online self-management program for adults with arthritis pain. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 38, 483–496.

Vallejo, M. A., Ortega, J., Rivera, J., Comeche, M. I., & Vallejo-Slocker, L. (2015). Internet versus face-to-face group cognitive-behavioral therapy for fibromyalgia: A randomized control trial. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 68, 106–113.

van Ballegooijen, W., Cuijpers, P., van Straten, A., Karyotaki, E., Andersson, A., Smit, J. H., et al. (2014). Adherence to internet-based and face-to-face cognitive behavioural therapy for depression: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 9, e100674.

van Beugen, S., Ferwerda, M., Hoeve, D., Rovers, M. M., Spillekom-van Koulil, S., van Middendorp, H., et al. (2014). Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for patients with chronic somatic conditions: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16, e88.

Weise, C., Kleinstäuber, M., & Andersson, G. (2016). Internet-delivered cognitive-behavior therapy for tinnitus: A randomized controlled trial. Psychosomatic Medicine, 78, 501–510.

Williams, D. A., Kuper, D., Segar, M., Mohan, N., Sheth, M., & Clauw, D. J. (2010). Internet-enhanced management of fibromyalgia: A randomized controlled trial. Pain, 151, 694–702.

Wilson, M., Hewes, C., Barbosa-Leiker, C., Mason, A., Wuestney, K. A., Shuen, J. A., et al. (2018). Engaging adults with chronic disease in online depressive symptom self-management. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 40, 834–853.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Swati Mehta, Vanessa A. Peynenburg, Heather D. Hadjistavropoulos declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and animal rights and Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Appendix

Appendix

# | Searches |

|---|---|

1 | Internet.mp. or exp Internet/ |

2 | Therapy, computer-assisted/or computers/ |

3 | Online Systems/or online.mp. |

4 | Cognitive behavioral therapy.mp. or Cognitive Therapy/ |

5 | Behavior Therapy/or behavioral therapy.mp. |

6 | cbt.mp. |

7 | Chronic disease/or chronic health.mp. |

8 | Health condition.mp. |

9 | Physical health.mp. |

10 | Exp musculoskeletal diseases/or respiratory tract diseases/or exp otorhinolaryngologic diseases/or nervous system diseases/or exp eye diseases/or exp cardiovascular diseases/or exp “wounds and injuries”/ |

11 | 1 or 2 or 3 |

12 | 4 or 5 or 6 |

13 | 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 |

14 | 11 and 12 and 13 |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Mehta, S., Peynenburg, V.A. & Hadjistavropoulos, H.D. Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic health conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Behav Med 42, 169–187 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-018-9984-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-018-9984-x