Abstract

Depression is common in individuals with multiple sclerosis (MS). While psychotherapy is an effective treatment for depression, not all individuals benefit. We examined whether baseline social support might differentially affect treatment outcome in 127 participants with MS and depression randomized to either Telephone-administered Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (T-CBT) or Telephone-administered Emotion-Focused Therapy (T-EFT). We predicted that those with low social support would improve more in T-EFT, since this approach emphasizes the therapeutic relationship, while participants with strong social networks and presumably more emotional resources might fare better in the more structured and demanding T-CBT. We found that both level of received support and satisfaction with that support at baseline did moderate treatment outcome. Individuals with high social support showed a greater reduction in depressive symptoms in the T-CBT as predicted, but participants with low social support showed a similar reduction in both treatments. This suggests that for participants with high social support, CBT may be a more beneficial treatment for depression compared with EFT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic and disabling autoimmune disease of the central nervous system. The disease can produce a wide variety of symptoms, including impaired motor function or feeling in limbs, debilitating fatigue, pain, loss of bowel or bladder control, sexual dysfunction, blindness due to optic neuritis, impaired cognitive functioning and emotional symptoms (Goodkin 1992; Mohr and Cox 2001). Depression is common—individuals with MS have a lifetime risk of major depressive disorder of over 50% (Patten et al. 2003; Sadovnick et al. 1996; Schubert and Foliart 1993)—and depression is likely both a primary symptom of MS and secondary to the unpredictability and impairment of the disease. Depression not only exacerbates functional impairment in patients (Mohr et al. 2007), there is also evidence that it also increases inflammatory processes in MS (Gold and Irwin 2006; Mohr et al. 2001a, b).

Both psychotherapy and antidepressant medications have been shown to be effective in reducing depression in patients with MS (Foley et al. 1987; Mohr et al. 1999, 2000b). One issue MS patients face, however, is difficulty in accessing mental health care, particularly psychotherapy. Like many other people living with chronic illness, MS patients face fatigue and mobility issues that can make it difficult for them to physically get to regular appointments. Telephone therapy may help overcome some of the barriers to direct care that people with chronic medical conditions often face (Mohr et al. 2006). Telephone therapy has been found to be an effective modality for delivering depression treatment in several studies (Miller and Weissman 2002; Mohr et al. 2000a, 2005; Sandgren and McCaul 2003; Simon et al. 2004). In fact, a recent study found that telephone therapy was as effective as face-to-face therapy in the treatment of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (Lovell et al. 2006).

But while the telephone administration of psychotherapy for depression may overcome certain barriers to care, there remains the vexing problem that even the most effective depression treatments (no matter how they are delivered) fail to help a large percentage of the patients in randomized control trials—25–50% do not show improvement at post-treatment, and among those who do improve, many relapse by the 1–2 year follow-ups (DeRubeis et al. 2005; Westen and Morrison 2001). This may partly be due to the fact that different patients may fare better in one type of treatment over another, depending on individual characteristics and factors. The key to improving outcome, then, is to better match patients to particular treatments. In searching for variables that may differentially affect outcome in one depression approach versus another, social support stands out as a likely treatment outcome moderator.

There is a well-documented literature establishing a relationship between social support and depression. In naturalistic studies it has been found that lower levels of social support are associated with higher levels of depression (for a review, see Bagby et al. 2002; Brugha et al. 1987; Grant et al. 2006). Others have described the lack of a social support structure as an important vulnerability factor for depression in both healthy (Bosworth et al. 2002; Bromberger et al. 1994; Ezquiaga et al. 1998; Vanderhorst and McLaren 2005) and medically ill populations (Liu et al. 2006; Revenson et al. 1991). Some studies also suggest that social support positively predicts better treatment outcome in depression. In several controlled trials for inpatient treatment of depression, higher levels of social support predicted improvement (George et al. 1989; Keitner et al. 1997; Nasser and Overholser 2005; Szadoczky et al. 2004). Others have reported similar results in outpatients who received either psychopharmacological interventions or psychotherapy for depression (Ezquiaga et al. 1998; Lyness et al. 2006; Oxman and Hull 2001).

However, studies do not show a uniformly positive relationship between social support and improvement in depression in treatment outcome research (Beekman et al. 1997; Paykel et al. 1996), suggesting that the relationship of social support to outcome may vary with the treatment approach. In a study by Helgeson and colleagues, individuals with high levels of social support fared less well in a peer support group than did those who reported low levels of social support at baseline (Helgeson et al. 2000). One explanation for this finding is that those with low social support benefited more from group therapy than their high social support cohorts because the treatment provides what these individuals lack—group members’ empathy and support. In the realm of individual therapy, some theoretical approaches place a heavy emphasis on the therapeutic relationship, and it is possible that individuals with low social support might benefit more from the direct support provided by these depression treatments compared with more practical, skill-building approaches such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). Those with high social support, on the other hand, may have more emotional resources to take on the challenging tasks of CBT including doing homework, testing out new behaviors, and developing new skills.

In the current study, we tested whether social support moderates outcome in two telephone treatments targeting depressive symptoms in patients with MS: Telephone-administered Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (T-CBT) and Telephone-administered Emotion-Focused Therapy (T-EFT). T-EFT is based on Greenberg’s Process-Experiential therapy manual (Greenberg et al. 1993), and is a humanistic approach that emphasizes using the therapeutic bond to help patients express and process emotional material. T-EFT also includes specific interventions that target self-criticism and dependence, which can interfere with relationships and social support. While the therapeutic alliance between the therapist and patient is an important factor in T-CBT as well (Beckner et al. 2007), T-CBT is highly structured and session time is focused on teaching communication and problem-solving skills, fatigue management planning, and cognitive restructuring of depressogenic automatic thoughts and beliefs. We predicted that MS patients with low levels of received social support and low satisfaction with that support at baseline would improve more in the T-EFT condition, while patients who score high on these baseline social support variables would do preferentially well in the T-CBT condition. We looked at both level of received social support and satisfaction with that support separately, given that these constructs are conceptually unique (i.e., one may have large social network but feel unhappy with the quality of that support). Several studies have also found that satisfaction with support (quality) may be a better predictor of depression outcome than quantity of support received (Beedie and Kennedy 2002; Rintala et al. 1992).

Methods

This study is a secondary analysis from a randomized clinical trial examining telephone-administered psychotherapy treatments for depression among patients with multiple sclerosis (please see Mohr et al. 2005 for additional details regarding methods and primary treatment outcomes).

Participants

Participants were recruited to participate in a telephone-administered depression treatment by letter to Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Group of Northern California members and advertising and outreach through regional chapters of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. All potential participants were verbally consented over the telephone prior to a screening interview. If after the initial screening process participants were still eligible to participate, they were mailed a written consent before being more thoroughly assessed on all inclusion and exclusion criteria. The consent process was approved by the Human Subjects Review Committees of both the University of California at San Francisco and Kaiser Permanente. Participants were paid $10.00 to $50.00 per assessment, depending on the length of the assessment.

Inclusion criteria included: (1) a neurologist confirmed diagnosis of MS, (2) functional impairment resulting in limitations in activity as measured by a score of at least 3 (out of a total of 6) on one or more functional areas assessed by the Guy’s Neurological Disability Scale (Sharrack and Hughes 1999), (3) a score of at least 16 on the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II, Beck et al. 1996) and at least 14 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D, Hamilton 1960), (4) ability to speak and read English, (5) at least age 18. Participants were excluded if they (1) met criteria for dementia using a standard battery for MS (Mohr et al. 2001b), (2) were currently in psychotherapy, (3) showed severe psychopathology including psychosis, current substance abuse, plan and intent to commit suicide, (4) were currently experiencing an MS exacerbation, (5) reported physical deficits that would prevent participation in treatment or assessment, including inability to speak, read, or write, and (6) use of medications, other than antidepressants, that impact mood (e.g. steroidal anti-inflammatories). Use of antidepressant medications was not exclusionary.

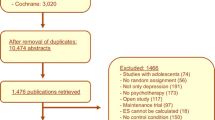

Among the 748 participants who completed a telephone screen, 223 were eligible for and agreed to a complete eligibility assessment. Of those, 150 were found to be eligible for randomization, though 23 (15.3%) refused to be randomized. Therefore, 127 participants were randomized: 62 were assigned to the T-CBT condition and 65 were assigned to the T-EFT condition. There were 3 participants in the T-CBT condition and four in the T-EFT condition who dropped out of treatment; of those, 2 in the T-CBT condition and 3 in the T-EFT condition completed the remaining assessments. Two participants discontinued assessments once treatment was completed in the T-CBT condition, and 3 in the T-EFT condition.

The final intent-to-treat sample of 127 was largely female (77%) and Caucasian (90%), with 5% African American, 1.5% Hispanic, and about 1% Asian. The gender and ethnicity of the sample reflects the epidemiology of multiple sclerosis, which largely afflicts women and Caucasians. The mean age of participants was 47.96 (SD = 10.10). The sample was educated (M = 15.36 years, SD = 2.56), with 26% employed, 11% unemployed, over half on disability (54%), and 9% indicating “other.” The monthly household income was M = $3,825.69 (SD = $2,612.09). The majority (78%) lived with a spouse or partner, and the mean number of people in the household was between 2 and 3 (M = 2.54, SD = 1.32). Just over half of the sample was taking medication for depression (55% in each group). The two treatment groups did not differ significantly on any of these measures (ps > 0.41; see Table 1 for demographics by group).

Treatments

T-CBT and T-EFT are manualized psychotherapy treatments for depression. Both treatments were delivered over 16 weekly 50-min telephone sessions by licensed, doctoral-level psychologists with 1–5 years of postdoctoral practice. While CBT and EFT both include many “non-specific” characteristics of therapy (active listening by the therapist, a supportive therapeutic relationship), each had their own unique therapeutic interventions (see below). Adherence to treatment was confirmed (see section on clinicians below for fidelity measurement).

Telephone-administered Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (T-CBT)

T-CBT is a structured, manualized approach based on standard CBT for depression (Beck et al. 1979; Beck 1995). We have developed a participant workbook to guide the treatment (Mohr et al. 2001a, 2000a). The manual included five chapters that are used by all participants which focused on teaching the participants methods to identify and modify depressogenic thoughts, increase the number pleasant activities in their life, enhance effective problem solving, and manage interpersonal difficulties (through improving communication skills and increasing social support). There were also 11 optional modules for specific problems such as fatigue management and sexual difficulties. The participants worked with their therapist to identify areas they believe to be particularly problematic from these 11 modules, and to focus on and apply the skills learned in every day settings. The T-CBT manual did not include interventions specific to T-EFT (below), such as having patients focus on deepening their emotional experience by forming an image of the emotion and describing it’s shape, color, and so on.

Telephone-administered Emotion Focused Therapy (T-EFT)

T-EFT is a manualized process-experiential therapy developed by Greenberg and adapted for this study (Greenberg et al. 1993). The approach was chosen because of its emphasis on non-CBT components, including a primary focus on empathic attunement and the facilitation of communicating emotional experience in the moment. T-EFT emphasizes the creation of a genuine, supportive and validating therapeutic relationship as the necessary condition for using process interventions aimed at carefully exploring emotional experience. Through careful attunement to affective material in the moment, T-EFT therapists help clients work though emotional difficulties presumed to underlie depression. In the current study, T-EFT therapists were instructed to avoid interventions that focused on modifying cognitions, behaviors, or skill attainment, to minimize the overlap between the two approaches. Some of the processes used in Greenberg’s original treatment, such as empty chair and two-chair work, were impossible given that the therapy was conducted over the phone. T-EFT was also chosen because it successfully controlled for all non-specific factors associated with T-CBT, including the therapeutic relationship and the use of a manualized treatment.

Clinicians and treatment fidelity

A total of 9 therapists were used. The 5 T-CBT therapists were trained in the model and reported that they primarily used CBT in their practices. The 4 T-EFT therapists expressed a strong belief that change in therapy is primarily driven by the therapeutic relationship. In addition, all T-EFT therapists denied using CBT techniques or using skill-based training in their practices. Therapist adherence to the model was rated by blinded research assistants with 2 days of training on rating adherence. Two sessions from each therapist were randomly selected for rating, using a modified version of the Cognitive Therapy Scale (Vallis et al. 1986) that included all original items as well as some specific to T-EFT therapeutic procedures. T-CBT therapists were rated as performing significantly more cognitive-behavioral interventions on the summary score (t(240) = −49.36, p = 0.001) and overall rating of CBT performance (t(240) = 54.40, p = 0.01). T-EFT therapists were rated as making significantly more interventions aimed at evoking emotional expression (t(240) = 33.67, p = 0.01) and fostering participants’ awareness of internal experience (t(240) = 4.03, p = 0.01).

Assessments

Outcome measures were assessed at baseline and week 16 (post-treatment). Social support was measured at baseline. Self-report measures were mailed to participants along with stamped addressed return envelopes. All interview assessments were conducted over the telephone by trained and blinded clinical evaluators. Participants were instructed to complete all self-report measures on the day of the interview; if the measures were not completed at the onset of the interview, the assessment was rescheduled. In order to maintain the blind, all assessment interviews were preceded by a request not to discuss any aspect of therapy. In addition, all interviews were audiotaped and the clinical evaluators met monthly to co-rate an assessment tape in order to calibrate and maintain reliabilities. Eight evaluators were used during the study.

Social support

Social support was assessed using the UCLA-Social Support Inventory (UCLA, Dunkel-Schetter et al. 1986). This measure is designed to be flexible in order to accommodate different research questions. We looked at items tapping two aspects of social support: level of received support and satisfaction with that support. Level of received support included 5 items such as “When you were stressed, how often did you receive encouragement and reassurance?” and “How often did you feel loved and cared for?” The participant then rated on a 5-point scale the degree to which this support was provided by four different sources of support: partner/family members, friends, medical providers, and organizations/groups. Following each of these questions, we asked how satisfied the participants felt with that support (5 satisfaction questions). Both level of received support and satisfaction with support had good reliability (level of received support, α = 0.87; satisfaction with that support, α = 0.84).

Depression severity

Depressive symptoms were assessed at baseline and post-treatment using the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II, Beck et al. 1996) and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D, Hamilton 1960). The BDI-II is a 21-item self-report measure of depression, which is both widely used and reliable. In addition, the BDI-II is not confounded with MS symptom severity (Aikens et al. 1999; Moran and Mohr 2005). The HAM-D is a 17-item semi-structured interview that was adapted for use over the telephone (Potts et al. 1990). Raters were trained by listening to previous tapes and engaging in mock interviews. Reliability checks were conducted throughout the study duration; using interclass correlations, reliabilities averaged 0.89 (range, 0.75–0.97).

MS-related disability

MS-related disability was assessed as part of the inclusion criteria in the study, and was determined using The Guy’s Neurological Disability Scale (Sharrack and Hughes 1999), which is a structured interview that assesses 11 basic areas of function (eg, limb function and vision). It produces a single score that is highly related (r = 0.81) to objective measures of functional impairment based on neurologist examination. We dropped the item assessing mood because it is confounded with our outcome measures. Each item rates a basic area of functioning from 1 (no symptoms) to 5 (a specific criterion reflecting extremely severe impairment). A 3 on any item reflects the point at which the functional impairment interferes with normal daily functioning.

Results

Baseline measures

Baseline variables were analyzed using the student t-test for continuous variables and chi square analysis for categorical variables to confirm integrity of randomization. None of the baseline demographic variables differed between treatment groups (see Table 1). We also confirmed that the treatment groups did not differ at baseline on depression severity. Means and standard deviations on the BDI-II for the T-EFT group and T-CBT groups respectively were: M = 28.32, SD = 7.91; M = 27.00, SD = 7.78; p = 0.34. Means for the two groups on the Hamilton were: M = 21.66, SD = 3.53; M = 21.35, SD = 3.90; p = 0.65. In addition, no differences between treatment groups were found for the baseline social support measures: level of received support (M = 49.60, SD = 12.56; M = 48.32, SD = 11.40; p = 0.55) and satisfaction with support (M = 21.64, SD = 5.34; M = 20.73, SD = 5.89; p = 0.36).

Main effects and moderator analyses

Hierarchical multiple linear regression techniques were used to examine the interaction effect between baseline social support and treatment condition on depression outcomes. Because demographics and disease related variables are not specifically relevant to the question, are unrelated to baseline social support variables, and are known not to affect these outcomes (Mohr et al. 2005), they were not included in the analyses. This reduces the risk of spurious findings related to overfitting regression models (Babyak 2004).

Each social support measure (level of received support and satisfaction with support) was tested separately. Baseline depression was entered first to control for depression severity at the start of treatment, given that it was a significant predictor of end of treatment depression in every model (ps ≤ 0.01). Baseline social support was entered next, followed by treatment assignment, and finally the cross-product of treatment condition and social support at baseline. The direction of the interaction in significant models was explored using scatter plots of the unstandardized predicted value from the interaction model and the social support variable at baseline. Examination of the moderation effect was also done within each treatment condition for each social support outcome found to have a significant moderation effect with treatment. The main effect model was tested separately within the T-EFT and T-CBT conditions to determine the relationship between baseline social support and depression outcome within each treatment condition, controlling for baseline depression level.

Results of the analyses are displayed in Tables 2 and 3. There were no significant main effects for either baseline level of received social support or satisfaction with support on the BDI-II or the HAM-D at end of treatment (ps ≥ 0.13). However, the two social support variables did appear to moderate treatment outcome for depression. First, a significant interaction between level of received support and treatment was found when predicting end of treatment residualized BDI-II and HAM-D scores (ps < 0.03). The meaning of these interactions was examined using separate regressions within each treatment condition, as displayed in Fig. 1. For participants assigned to the T-CBT condition, higher baseline received support was associated with lower residualized end-of-treatment BDI-II and HAM-D scores (β = −0.33 and β = −0.35, respectively, ps ≤ 0.01). This relationship was not significant for those assigned to T-EFT (ps ≥ 0.43). Next, a significant interaction was observed for satisfaction with support and treatment when predicting end of treatment residualized BDI-II and HAM-D scores (ps ≤ 0.01). Again looking within each treatment (see Fig. 2), baseline satisfaction with support significantly predicted both end of treatment BDI-II and HAM-D scores within the T-CBT condition (β = −0.42 and β = −0.44, respectively, ps ≤ 0.01), but not within the T-EFT condition (ps ≥ 0.33).Footnote 1

Relationship between level of received support at baseline and post-treatment depressive symptoms (residualized BDI-II and HAM-D scores) as a function of treatment. Separate regression analyses demonstrated that level of received social support predicted depression scores within the Telephone-administered Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (T-CBT) condition, but not within the Telephone-administered Emotion Focused Therapy (T-EFT) condition

Relationship between satisfaction with support at baseline and post-treatment depressive symptoms (residualized BDI-II and HAM-D scores) as a function of treatment. Separate regression analyses demonstrated that support satisfaction predicted depression scores within the Telephone-administered Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (T-CBT) condition, but not within the Telephone-administered Emotion Focused Therapy (T-EFT) condition

To further examine the moderation effect, the two social support variables were subdivided into binary categorical variables using the median social support value as the cut-point. This allowed us to directly compare treatment outcome for individuals who entered the study with either low or high social support using a t-test. Figures 3 and 4 show the mean depression scores and standard errors in the high and low social support groups (received support and satisfaction, respectively) by treatment assignment. Among participants who scored below the median on the received support scale, t-tests showed no difference between treatments for either the BDI-II or the HAM-D (ps ≥ 0.31). However, t-tests conducted with participants who scored above the median on received support showed that those in the T-CBT group had greater reduction in depression on the HAM-D (p = 0.04); this relationship only reached a trend level on the BDI-II (p = 0.087). For satisfaction with support, the t-tests conducted with those below the median again showed no significant differences between treatments in change scores for the BDI-II or HAM-D (ps ≥ 0.41). However, those who fell above the median did significantly better in the T-CBT compared with the T-EFT on both the BDI-II and HAM-D (ps ≤ 0.03).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine whether two bona fide depression treatments differentially impact depressive symptoms depending on the participant’s baseline level of social support. We found that both the level of social support participants reported receiving at baseline, as well as their satisfaction with that support, moderated treatment outcome among participants with MS and depression. Specifically, individuals with higher levels of received support and satisfaction with their social support network showed greater reductions in depressive symptoms when enrolled in T-CBT compared with T-EFT. Participants with low social support at baseline improved similarly in both treatments. This suggests that depression outcomes do vary depending on baseline levels of social support and treatment type, but that the important differences are only seen in participants with high social support. These results have important implications for matching participants to treatments. For participants with high social support, CBT may be a more beneficial treatment for depression than emotion-focused therapy. These results need to be replicated, however, given recent findings that challenge the robustness of interaction findings (Risch et al. 2009).

While the data supported our prediction that those with high social support would see greater reductions in depression with a cognitive-behavioral approach compared with an experiential emotion-focused approach, there are several possible explanations for this finding. Our hypothesis was based on the idea that individuals with a strong social network do not need the supportive “ear” of a therapist in the same way that those with little social support do. They already have empathetic people in their life; what they need to do is make some behavioral changes to break the depression cycle (i.e., challenge negative interpretations, engage in pleasurable activities, etc.). We also suspect that high social support may be a “marker” for certain skills or traits that facilitate improvement in T-CBT, such as greater openness to trying new behaviors, or more cognitive resources for learning new skills. Additional research is needed to investigate these or other possible explanations.

In contrast, we expected that participants with lower baseline levels of social support (both level of received and satisfaction with that support) would improve more in the T-EFT treatment. Because the T-EFT intervention focuses specifically on the therapeutic relationship—encouraging clients to express and explore emotional issues within the context of this safe and empathetic bond—we expected that this approach would fill an important social support gap for those who lack family and friends with whom they can talk to. The data did not support this hypothesis: participants low in social support improved similarly in both treatment groups.

There are a number of ways to interpret this outcome. It may be that while the T-CBT therapists are focused more on education and skills training, they are also providing a supportive bond within the therapeutic relationship. Indeed, evidence suggests that the therapeutic alliance is as strong between clients and therapists using a cognitive-behavioral approach compared to therapists using various process-oriented approaches that specifically emphasize the therapeutic bond (Beckner et al. 2007). An alternative interpretation is that among participants with low social support, similar levels of improvement resulted for different therapeutic processes. For example, those who received T-EFT may have responded positively to the focus on the therapy relationship, while those in the T-CBT may have benefited from the CBT skills training. No matter what the explanation, however, it is clear that for participants who entered the study with a weak social network, it didn’t matter which treatment they received: both reduced depression similarly.

An important caveat is that that all of the participants were managing a chronic, debilitating medical illness. Social support may interact with depression in a unique way within certain medical populations, like MS. While short-term illness often elicits social support, chronic illness can exhaust people’s network and strain relations with family and close friends, leading to isolation or less satisfaction with one’s social support. Physical symptoms and related disability can also make attending social activities difficult. Participants in this study all had at least one symptom that impaired their daily functioning (i.e., mobility issues, fatigue, etc.) that could have impacted social relationships. It is therefore difficult to know whether the findings in this study would generalize to individuals in good health or without a disability.

It is also important to consider the fact that both treatments in this study were delivered over the phone. While the data indicates that both T-CBT and T-EFT are effective in reducing depression (see Mohr et al. 2005), it is difficult to know whether the interaction of social support with the treatments was affected by their mode of delivery. There is evidence that good rapport was established and maintained in therapy, and did not differ between conditions (Beckner et al. 2007). However, non-verbal communication may be essential to fully facilitate the emotional processing that is the core of Emotion-Focused Therapy. It remains an empirical question whether those with low social support might indeed benefit more from an experiential approach emphasizing the therapeutic relationship if it was delivered face-to-face.

In summary, if our findings are confirmed in subsequent research, it may be important in treating depression in people with chronic illness that their baseline level of social support is assessed prior to selecting a treatment approach. Although our study suggests that individuals who report low social support may do just as well in a variety of treatments, this does not appear to be the case for individuals with MS who entered treatment for depression with a relatively strong social support network. Matching these individuals with a CBT based treatment may significantly improve the likelihood of a positive outcome.

Notes

In our exploratory analyses, we also looked at items on our social support measure that tap instrumental versus emotional support, to determine whether type of support might moderate outcome differently. We obtained the same moderating and within-treatment group findings using these support variables: participants with higher instrumental or higher emotional support at baseline improved more in the T-CBT group, while level of instrumental or emotional support did not affect depression outcome in the T-EFT group.

References

Aikens, J. E., Reinecke, M. A., Pliskin, N. H., Fischer, J. S., Wiebe, J. S., McCracken, L. M., et al. (1999). Assessing depressive symptoms in multiple sclerosis: Is it necessary to omit items from the original Beck Depression Inventory? Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 22(2), 127–142.

Babyak, M. A. (2004). What you see may not be what you get: A brief, nontechnical introduction to overfitting in regression-type models. Psychosomatic Medicine, 66(3), 411–421.

Bagby, R. M., Ryder, A. G., & Cristi, C. (2002). Psychosocial and clinical predictors of response to pharmacotherapy for depression. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 27(4), 250–257.

Beck, J. S. (1995). Cognitive therapy: Basics and beyond. New York: Guilford Press.

Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Beck depression inventory—second edition: Manual. San Antonio TX: Psychological Corporation.

Beckner, V., Vella, L., Howard, I., & Mohr, D. C. (2007). Alliance in two telephone-administered treatments: Relationship with depression and health outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(3), 508–512.

Beedie, A., & Kennedy, P. (2002). Quality of social support predicts hopelessness and depression post spinal cord injury. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 9(3), 227–234.

Beekman, A. T., Penninx, B. W., Deeg, D. J., Ormel, J., Braam, A. W., & van Tilburg, W. (1997). Depression and physical health in later life: Results from the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam (LASA). Journal of Affective Disorders, 46(3), 219–231.

Bosworth, H. B., Hays, J. C., George, L. K., & Steffens, D. C. (2002). Psychosocial and clinical predictors of unipolar depression outcome in older adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17(3), 238–246.

Bromberger, J. T., Wisner, K. L., & Hanusa, B. H. (1994). Marital support and remission of treated depression. A prospective pilot study of mothers of infants and toddlers. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 182(1), 40–44.

Brugha, T., Bebbington, P. E., MacCarthy, B., Potter, J., Sturt, E., & Wykes, T. (1987). Social networks, social support and the type of depressive illness. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 76(6), 664–673.

DeRubeis, R. J., Hollon, S. D., Amsterdam, J. D., Shelton, R. C., Young, P. R., Salomon, R. M., et al. (2005). Cognitive therapy vs medications in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(4), 409–416.

Dunkel-Schetter, C., Feinstein, L., & Call, J. (1986). UCLA Social Support Inventory (UCLA-SSI) (Unpublished psychometric instrument). Los Angeles: University of California, Los Angeleso (Document Number).

Ezquiaga, E., Garcia, A., Bravo, F., & Pallares, T. (1998). Factors associated with outcome in major depression: A 6-month prospective study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 33(11), 552–557.

Foley, F. W., Bedell, J. R., LaRocca, N. G., Scheinberg, L. C., & Reznikoff, M. (1987). Efficacy of stress-innoculation training in coping with multiple sclerosis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55, 919–922.

George, L. K., Blazer, D. G., Hughes, D. C., & Fowler, N. (1989). Social support and the outcome of major depression. British Journal of Psychiatry, 154, 478–485.

Gold, S. M., & Irwin, M. R. (2006). Depression and immunity: Inflammation and depressive symptoms in multiple sclerosis. Neurologic Clinics, 24(3), 507–519.

Goodkin, D. E. (1992). The natural history of multiple sclerosis. In R. A. Rudick & D. E. Goodkin (Eds.), Treatment of multiple sclerosis: Trial design, results and future perspectives (pp. 17–46). New York: Springer-Verlag.

Grant, J. S., Elliott, T. R., Weaver, M., Glandon, G. L., Raper, J. L., & Giger, J. N. (2006). Social support, social problem-solving abilities, and adjustment of family caregivers of stroke survivors. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 87(3), 343–350.

Greenberg, L. S., Rice, L. N., & Elliott, R. (1993). Facilitating emotional change: The moment-by-moment process. New York: Guilford Press.

Hamilton, M. (1960). A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 23, 56–62.

Helgeson, V. S., Cohen, S., Schulz, R., & Yasko, J. (2000). Group support interventions for women with breast cancer: Who benefits from what? Health Psychology, 19(2), 107–114.

Keitner, G. I., Ryan, C. E., Miller, I. W., & Zlotnick, C. (1997). Psychosocial factors and the long-term course of major depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 44(1), 57–67.

Liu, C., Johnson, L., Ostrow, D., Silvestre, A., Visscher, B., & Jacobson, L. P. (2006). Predictors for lower quality of life in the HAART era among HIV-infected men. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 42(4), 470–477.

Lovell, K., Cox, D., Haddock, G., Jones, C., Raines, D., Garvey, R., et al. (2006). Telephone administered cognitive behaviour therapy for treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder: Randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. BMJ, 333(7574), 883.

Lyness, J. M., Heo, M., Datto, C. J., Ten Have, T. R., Katz, I. R., Drayer, R., et al. (2006). Outcomes of minor and subsyndromal depression among elderly patients in primary care settings. Annals of Internal Medicine, 144(7), 496–504.

Miller, L., & Weissman, M. (2002). Interpersonal psychotherapy delivered over the telephone to recurrent depressives. A pilot study. Depress Anxiety, 16(3), 114–117.

Mohr, D. C., Boudewyn, A. C., Goodkin, D. E., Bostrom, A., & Epstein, L. (2001a). Comparative outcomes for individual cognitive-behavior therapy, supportive-expressive group psychotherapy, and sertraline for the treatment of depression in multiple sclerosis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(6), 942–949.

Mohr, D. C., & Cox, D. (2001). Multiple sclerosis: Empirical literature for the clinical health psychologist. Journal of Clinical Psycholology, 57(4), 479–499.

Mohr, D. C., Goodkin, D. E., Islar, J., Hauser, S. L., & Genain, C. P. (2001b). Treatment of depression is associated with suppression of nonspecific and antigen-specific T(H)1 responses in multiple sclerosis. Archives of Neurology, 58(7), 1081–1086.

Mohr, D. C., Goodkin, D. E., Masuoka, L., Dick, L. P., Russo, D., Eckhardt, J., et al. (1999). Treatment adherence and patient retention in the first year of a Phase-III clinical trial for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis, 5(3), 192–197.

Mohr, D. C., Hart, S. L., Howard, I., Julian, L., Vella, L., & Feldman, M. D. (2006). Barriers to psychotherapy among depressed and non-depressed primary care patients. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 32(3), 254–258.

Mohr, D. C., Hart, S. L., Julian, L., Catledge, C., Honos-Webb, L., Vella, L., et al. (2005). Telephone-administered psychotherapy for depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(9), 1007–1014.

Mohr, D. C., Hart, S., & Vella, L. (2007). Reduction in disability in a randomized controlled trial of telephone-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy. Health Psychology, 26(5), 554–563.

Mohr, D. C., Likosky, W., Bertagnolli, A., Goodkin, D. E., Van Der Wende, J., Dwyer, P., et al. (2000a). Telephone-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy for the treatment of depressive symptoms in multiple sclerosis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(2), 356–361.

Mohr, D. C., Likosky, W., Bertagnolli, A., Goodkin, D. E., Van Der Wende, J., Dwyer, P., et al. (2000b). Telephone-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy for the treatment of depressive symptoms in multiple sclerosis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(2), 356–361.

Moran, P. J., & Mohr, D. C. (2005). The validity of Beck Depression Inventory and Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression items in the assessment of depression among patients with multiple sclerosis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 28(1), 35–41.

Nasser, E. H., & Overholser, J. C. (2005). Recovery from major depression: The role of support from family, friends, and spiritual beliefs. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 111(2), 125–132.

Oxman, T. E., & Hull, J. G. (2001). Social support and treatment response in older depressed primary care patients. Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 56(1), P35–P45.

Patten, S. B., Beck, C. A., Williams, J. V., Barbui, C., & Metz, L. M. (2003). Major depression in multiple sclerosis: A population-based perspective. Neurology, 61(11), 1524–1527.

Paykel, E. S., Cooper, Z., Ramana, R., & Hayhurst, H. (1996). Life events, social support and marital relationships in the outcome of severe depression. Psychological Medicine, 26(1), 121–133.

Potts, M. K., Daniels, M., Burnam, M. A., & Wells, K. B. (1990). A structured interview version of the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: Evidence of reliability and versatility of administration. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 24(4), 335–350.

Revenson, T. A., Schiaffino, K. M., Majerovitz, S. D., & Gibofsky, A. (1991). Social support as a double-edged sword: The relation of positive and problematic support to depression among rheumatoid arthritis patients. Social Science and Medicine, 33(7), 807–813.

Rintala, D. H., Young, M. E., Hart, K. A., Clearman, R. R., & Fuhrer, M. J. (1992). Social support and the well-being of persons with spinal cord injury living in the community. Rehabilitation Psychology, 37(3), 155–163.

Risch, N., Herrell, R., Lehner, T., Liang, K. Y., Eaves, L., Hoh, J., et al. (2009). Interaction between the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR), stressful life events, and risk of depression: A meta-analysis. JAMA, 301(23), 2462–2471.

Sadovnick, A. D., Remick, R. A., Allen, J., Swartz, E., Yee, I. M., Eisen, K., et al. (1996). Depression and multiple sclerosis. Neurology, 46(3), 628–632.

Sandgren, A. K., & McCaul, K. D. (2003). Short-term effects of telephone therapy for breast cancer patients. Health Psychology, 22(3), 310–315.

Schubert, D. S., & Foliart, R. H. (1993). Increased depression in multiple sclerosis patients. A meta-analysis. Psychosomatics, 34(2), 124–130.

Sharrack, B., & Hughes, R. A. (1999). The Guy’s Neurological Disability Scale (GNDS): A new disability measure for multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis, 5(4), 223–233.

Simon, G. E., Ludman, E. J., Tutty, S., Operskalski, B., & Von Korff, M. (2004). Telephone psychotherapy and telephone care management for primary care patients starting antidepressant treatment: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 292(8), 935–942.

Szadoczky, E., Rozsa, S., Zambori, J., & Furedi, J. (2004). Predictors for 2-year outcome of major depressive episode. Journal of Affective Disorders, 83(1), 49–57.

Vallis, T. M., Shaw, B. F., & Dobson, K. S. (1986). The cognitive therapy scale: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54, 381–385.

Vanderhorst, R. K., & McLaren, S. (2005). Social relationships as predictors of depression and suicidal ideation in older adults. Aging and Mental Health, 9(6), 517–525.

Westen, D., & Morrison, K. (2001). A multidimensional meta-analysis of treatments for depression, panic, and generalized anxiety disorder: An empirical examination of the status of empirically supported therapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(6), 875–899.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This investigation was supported in part by Victoria Lemle Beckner’s National Multiple Sclerosis Society Postdoctoral Fellowship and by David C. Mohr’s NIMH grant MH59708 R01.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Beckner, V., Howard, I., Vella, L. et al. Telephone-administered psychotherapy for depression in MS patients: moderating role of social support. J Behav Med 33, 47–59 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-009-9235-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-009-9235-2