Abstract

The electrical properties of double perovskite Ho2NiTiO6 (HNT) are investigated by impedance spectroscopy in the temperature range 30–420 °C and frequency range 100 Hz to 1 MHz. The X-ray diffraction analysis reveals that the compound crystallizes in monoclinic phase. The imaginary part of impedance (Z″) as a function of frequency shows Debye type relaxation. The frequency dependence of Z″ peak is found to obey an Arrhenius law with an activation energy of 0.129 eV. Impedance data presented in the Nyquist plot (Z″ vs. Z′) are used to identify an equivalent circuit and to know the bulk and interface contributions. The complex impedance analysis of HNT exhibits the appearance of both the grain and grain-boundary contribution. The results of bulk ac conductivity as a function of temperature and frequency are presented. The activation energy (0.129 eV), calculated from the slope of log τ versus 103/T plot, is found to be the nearly same as calculated (0.130 eV) from dc conductivity. The frequency dependent conductivity spectra obey the power law.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The perovskite structure class ceramic material is one of the most commonly occurring and important in all of materials science and has been extensively investigated in the last decades. Physical properties of interest among perovskite are of great importance in microelectronics and telecommunication [1]. It is well known that structural distortions, vacancies and compositional modifications can induce a great variety of physical and chemical properties [2]. When the ideal perovskite structure with the general formula ABO3 is changed to introduce two different types of cations on the octahedral site of the primitive perovskite unit cell, the cationic ordering leads to a cubic complex superstructure perovskite so-called double perovskite with general stoichiometry A2BB′O6 [3]. This permits to infer the possibility of producing new materials by the introduction of a rare-earth or alkaline-earth ion A and B, B′ transition metal ions. In ideal structure of these compounds, there is a regular arrangement of corner-sharing B′O6 and B″O6 octahedra, alternating along the three directions of the crystal, with the voluminous A cations occupying the voids in between the octahedra. The crystal structure and physical properties of double perovskite oxides depend considerably on the size and valencies of the A, B′ and B″ cations. The capacity of perovskite structure to incorporate almost all the elements in the periodic table has resulted in materials showing a large range of properties including dielectric, piezoelectric, ferroelectric, optical, superconducting and magnetoresistive properties [4]. A large number of extensive studies relating to different aspects of these double perovskites have been made especially for their potential applications arising from their interesting electrical and magnetic properties [5, 6].

The complex impedance spectroscopy (CIS) is a useful technique to analyze the electrical properties of electroceramics. This technique offers several advantages such as the determination of relaxation frequency and separation of grain, grain boundary and grain-electrode effects. The complex impedance spectroscopic studies involve measurement of real and imaginary parts of impedance for a wide range of frequency. In recent years, this technique has become a well-accepted fundamental tool for characterizing ionic conductors in terms of ionic conductivity, electrode polarization and activation energy for ion migration. Moreover, this technique has been exploited to probe the solid electrolytes, particularly to distinguish the inter-grain, intra-grain conduction, micro-heterogeneity and electrode-material interface.

The extensive literature survey reveals that the detailed studies on the electrical properties of double perovskite using CIS technique received little attention. In the present investigation, we have carried out complex impedance formalism and relaxation process of the newly proposed double perovskite Ho2NiTiO6 ceramic material in the temperature range 30–420 °C (here we have shown 300–420 °C) and frequency range 100 Hz to 1 MHz.

Experimental procedure

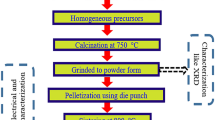

The complex perovskite oxide of Ho2NiTiO6 (HNT) was synthesized by solid state reaction technique. Nanopowders of Ho2O3 (Aldrich, 99.9+%), NiCO3 (Loba Chemie, 99%) and TiO2 (Laboratory reagent, 98%) were taken as primary raw materials and mixed in stoichiometric ratio in the presence of acetone (MERCK) for 12 h. The mixture was calcined in a Pt crucible at 1200 °C in air for 10 h and brought to room temperature under controlled cooling. The calcined powder was analyzed by X-ray diffraction technique and it was found to have monoclinic structure. The calcined sample was palletized into a circular disc (of thickness 1.6 mm and dia. 10 mm) using PVA as binder which was burnt out during high temperature sintering at 1250 °C for 5 h, and cooled slowly to room temperature by adjusting the cooling rate. The sintered pellets were polished to make both their faces parallel, electroded by high purity ultrafine silver paste and then connected to the LCR meter for their electrical characterization. In order to dry the paste the samples were evaporated onto both sides of the disc at 200 °C for 2 h prior to conducting experiment. Capacitance (C), impedance (Z), phase angle (φ) and conductance (G) of the sample were measured both as a function of frequency (100 Hz to 1 MHz) and temperature (300–420 °C) using a computer-controlled LCR meter (HIOKI-3552, Japan). The temperature was controlled with a programmable oven. All the electrical data were collected while heating at a rate of 0.05 °C/min. These results were found to be reproducible.

Results and discussion

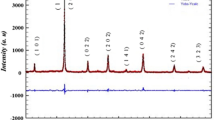

The X-ray diffraction pattern of HNT measured at room temperature is shown in Fig. 1. All the reflection peaks of the X-ray profile are indexed and lattice parameters are determined using a least-squares method with the help of a standard computer programmed (Crysfire). Good agreement between the observed and calculated interplanner spacing (d-values) suggests that the compound crystallizes in monoclinic phase at room temperature with β = 119.863° (A = 8.772741, B = 7.687233, C = 5.691668) and unit cell volume V = 332.87 Å3.

Figure 2 shows the angular frequency dependence of Z′(ω) and Z″(ω) of HNT as a function of temperature. In Fig. 2a, Z′ decreases with increase in frequency for all temperatures implies relaxation process in the sample. The magnitude of Z′ decreases at lower frequencies with increasing temperature which indicates increase in the ac conductivity and this can also be attributed to the fact that Z′ values decrease with increase of temperature indicating reduction of grains, grain boundaries and electrode interface resistance. This indicates the negative temperature coefficient of resistance (NTCR) in the sample. At higher frequencies (above 11 kHz) the value of Z′ merges for all the temperatures indicating release of space charges. From Fig. 2b it is clear that the position of the peak in Z″ is centred at the dispersion region of Z′ and it shifts to higher frequencies with increase in temperature which is mainly due to change in relaxation in the sample. The asymmetric broadening of the peaks suggests the presence of electrical process of the material with a distribution of relaxation times as indicated by the peak width. The relaxation species may be possibly due to presence of electron at low temperature and defects at higher temperature. In such a situation, the most probable relaxation time τm (= 1/ωm) from the position of the peak in the Z″ versus log ω plots can be determined (ωm = relaxation frequency, i.e. frequency at which Z″ is found to be maximum). The most probable relaxation time follows the Arrhenius law given by the relation:

where τ0 is the pre-exponential factor, E a is the activation energy, k is Boltzmann constant and T is the absolute temperature. The variation of relaxation time (log τ) with inverse of absolute temperature (103/T) is shown in the inset of Fig. 3, where the circles are the experimental data and the solid line is the least-squares straight-line fit. The activation energy E a calculated from the least-squares fit to the points is 0.129 eV. It is observed that the value of relaxation time is found to be decreasing with increasing temperature which indicates semiconductor behaviour of the sample.

Scaling behaviour of Z″ at various temperatures for Ho2NiTiO6. The temperature dependence of the most probable relaxation time (τm) obtained from the frequency-dependent plot of Z″ is shown in the inset where the symbols are the experimental points and the solid line is the least-squares straight-line fit

In polycrystalline samples, grains are semiconducting while the grain boundaries are insulating [7]. The semiconducting nature of the grains in ceramics is believed to be due to the loss of oxygen during high temperature sintering process.

If we plot the Z″(ω,T) data in the scaled coordinates, i.e. Z″(ω,T)/Z″max and log (ω/ωm), where ωm corresponds to the frequency of the peak value of Z″ in the Z″ versus log ω plots, the entire data of imaginary part of impedance can collapse into one master curve as shown in Fig. 3. Thus, the scaling behaviour of Z″ clearly indicates that the relaxation mechanism is nearly temperature independent.

Figure 4 shows the complex-plane impendence plots (called Nyquist plots, i.e. Z″ vs. Z′ plot) of different temperatures for HNT compound. In this Z-plot, one can expect a separation of the bulk phenomena from the surface phenomena [8, 9]. The surface (electrode) polarization as a highly capacitive phenomenon is characterized by larger relaxation times than the polarization mechanism in the bulk (grain interior). This fact usually results in the appearance of two separate area of semicircle in the Z″ and Z′ plots in which one representing the bulk effect at high frequencies while the other represents surface effect in lower frequency range. It is observed from Fig. 4 that the values of impedance decreases sharply as the temperature increases which indicates that the conductivity increases sharply with increase in temperature and showing the semiconducting behaviour of the material. It is observed from the inset of Fig. 4 that in the temperature range from 300 to 340 °C both the grain and grain-boundary contribution are present in this material. With the increase of temperature the grain contribution shifted to the higher frequency side and not observed in the measured frequency window, i.e. after 340 °C only grain-boundary contribution is dominated. As obtained from the intercept of the low frequency semicircle with the X-axis, the grain-boundary resistance (R gb) values at 300, 320, 340, 360, 380, 390, 400 and 420 °C are 3.234, 2.063, 1.221, 0.820, 0.670, 0.488, 0.372, and 0.315 MΩ, respectively. And the corresponding grain-boundary capacitance (C gb) values are 12.3 × 10−11, 9.21 × 10−11, 8.95 × 10−11, 7.67 × 10−11, 6.49 × 10−11, 6.17 × 10−11, 5.60 × 10−11 and 5.50 × 10−11 F. The corresponding relaxation times (τg) in this temperature range are 3.97 × 10−4, 1.90 × 10−4, 1.09 × 10−4, 0.63 × 10−4, 0.44 × 10−4, 0.30 × 10−4 and 0.21 × 10−4 s.

Figure 5 shows the variation of grain-boundary resistance as a function of temperature. It is clear that the grain-boundary resistance decreases sharply with rise in temperature up to 360 °C and then decreases slowly (Fig. 5). The rate of increase of grain-boundary conductivity is different in different regions, which means different activation energies involved in different temperatures regions for the conductivity due to grain-boundary.

The complex impedance plots of HNT at three temperatures 340, 360 and 400 °C is shown in Fig. 6. The values of grain and grain-boundary resistances and capacitances can be obtained by an equivalent circuit of two parallel resistance–capacitance (RC) elements connected in series (inset of Fig. 6). This RC elements give rise to two semicircular arcs on the complex-plane plot, representing the grain and grain-boundary effect. The equivalent electrical equations for grain is

where C g and C gb are the grain and grain-boundary capacitances and R g and R gb are the grain and grain-boundary resistances, respectively. We have fitted the experimental data using these expressions and the best fit of data at 340, 360 and 400 °C are shown by solid line in Fig. 6.

Figure 7 shows the log σac–log ω plot of frequency dependence of ac conductivity for HNT sample at different temperatures. It is obvious that the conductivity increases with increasing frequency and increasing temperatures (Fig. 7). At higher temperatures, a plateau is observed in the conductivity plots at lower frequency range where σac is frequency-independent. The plateau region extends to higher frequencies with the increase of temperature. Notice that at low frequencies, random diffusion of charge carriers via hopping gives rise to a frequency-independent conductivity. At higher frequencies, σac exhibit dispersion, increasing in a power law fashion and eventually becoming almost linear. The real part of conductivity σ in such a situation can be given by Jonscher power law [10]:

where σdc is the dc conductivity, ωH is the hopping frequency of charge carriers and n is the dimensionless frequency exponent. The experimental data are fitted to Eq. 4 at various temperatures (300–420 °C) where n is 0.65–0.69. The best fit of conductivity spectra is shown by solid lines in Fig. 7.

Frequency-dependent ac conductivity (σac) of Ho2NiTiO6 at various temperatures where the symbols are the experimental points and the solid lines represent the fitting to Eq. 4

Figure 8 shows the Arrhenius plot of ac conductivity of HNT at various frequencies. The activation energies calculated from the slopes of Arrhenius plots are given in Table 1. It is interesting to note that ac conductivity activation energy decreases with increasing frequency and different activation energies involved in different temperature regions in the conduction process.

The reciprocal temperature dependence of dc conductivity (σdc) is shown in Fig. 9 which obeys Arrhenius law. The activation energy for dc conductivity is found to be 0.130 eV. The values of activation energy indicate that the conductivity in HNT is mainly due to the hopping of charge carriers, because the activation energy corresponding to hopping process is small.

Conclusion

The complex perovskite oxide of Ho2NiTiO6 (HNT) was synthesized by solid state reaction technique. The X-ray diffraction analysis shows that the compound is monoclinic. Complex impedance analysis of the material reveals that both the grain and grain-boundary contribution are present in the relaxation process of HNT. The electrical properties of HNT can be described by RC equivalent circuit. A significant broadening of the Z″-peaks with rise in temperature suggests the presence of temperature-dependent relaxation process of the material. The decrease of relaxation time (τ) with increasing temperature represents the semiconductor behaviour of the sample. The activation energy (0.129 eV), calculated from the slope of log τ versus 103/T plot, is found to be the nearly same as calculated (0.130 eV) from dc conductivity. The values of activation energy indicate that the conductivity in HNT is mainly due to the hopping of charge carriers.

References

Cava RJ (2002) J Mater Chem 11:54

Hazen RM (1988) Sci Am 258:54

Ortiz-Diaz O, Rodriguez MJA, Fajardo F, Tellez DAL, Roa-Rojas J (2007) Phys B 398:248

Raveau B (2007) Prog Solid State Chem 35:171

Kobayashi KI, Kimura T, Sawada H, Terakura K, Tokura Y (1998) Nature 395:677

DeMarco M, Blackstead HA, Dow JD, Wu MK, Chen DY, Chien FZ, Haka M, Toorongian MS, Fridmann J (2000) Phys Rev B 62:14301

Singh SP, Singh AK, Pandey D (2003) J Mater Res 18:1

Mckubre MCH, Macdonald JR (1987) In: Macdonald JR (ed) Impedance spectroscopy. Wiley, New York

Gerhardt R (1994) J Phys Chem Solids 55:1491

Jonscher AK (1983) Dielectric relaxation in solids. Chelsea Dielectric Press, London

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahato, D.K., Dutta, A. & Sinha, T.P. Impedance spectroscopy analysis of double perovskite Ho2NiTiO6 . J Mater Sci 45, 6757–6762 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-010-4771-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-010-4771-2