Abstract

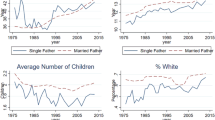

Using the 1977 Quality of Employment Survey and the 1997 National Study of the Changing Workforce this study showed that the temporal increase in fathers’ time with children was three times larger on non-workdays than workdays. Multivariate analyses revealed that both work (e.g., job autonomy) and family (presence of young children, dependence on wives’ earnings) factors increased men’s time with children. A decomposition analysis showed that changes in men’s behavior accounted for 70% of the temporal increase in fathers’ time with children, and that structural change in work and family life (especially wives’ increased contributions to household income) accounted for the remaining 30%. The implications of these findings and the need for further study of these issues were briefly discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Hall (2005) focused on cohort and aging effects on men’s paternal interaction with children (controlling for fathers’ race, education, work hours, and income, mother’s employment status, and number of children and age of the youngest child), finding that in the more recent cohort of fathers (surveyed in 1997), younger fathers spent more time with children on workdays and non-workdays.

Dependent children were defined as those who were biologically related to either the respondent or the spouse and who were ages 0–17 years old. Because of increased rates of divorce and remarriage (Bianchi et al. 2006), the 1997 sample included more step-fathers. Yet, data limitations precluded distinguishing biological children from step-children in the household, and from distinguishing between custodial fathers and fathers with joint custody of their children from a prior marriage.

In both survey years, respondents were asked to estimate their total annual earnings from their jobs including overtime, bonuses, commissions, etc. In addition, men were asked to provide an estimate of their wives’ annual pay; values on this measure were set to zero for men whose wives did not work for pay. Approximately 2 and 7% of men in 1977 and 1997, respectively, refused to report their earnings. Rather than deleting these cases, missing values were set to the year-specific mean and a binary measure of missing earnings was entered into the models to control for this assignment. But, because the missing earnings control had no impact on the results and failed to reach statistical significance, it was dropped from the analytic models.

In preliminary analyses, the models also controlled for wife’s employment status (two-thirds and 41% of fathers were married to a non-working spouse in 1977 and 1997, respectively) and wife’s hours worked per week (with zero assignment for non-working spouses, yielding means of 10 and 22 h per week in 1977 and 1997, respectively). Because wives’ work efforts correlate with their contributions to the couple’s income, including all three measures in the analytic models affected the results. That is, when spouse’s employment status and hours worked per week were included in the model, the effects of these measures were insignificant in predicting fathers’ time in child care, a non-finding consistent with findings reported in other studies (e.g., Bryant and Zick 1996a; Nock and Kingston 1988). More important, compared with the significant effect shown in Table 1, the effect of the relative income measure was insignificant when the analytic models also controlled for spouse’s employment status and hours worked. Yet, when the relative income measure was omitted from the analytic models, the two measures of spouse’s work attachment were insignificant in predicting fathers’ time with children. For reasons of parsimony and because of the theoretical importance of wives’ relative income, the measures of spouses employment status and hours worked were omitted from the model.

The scale was constructed from the mean of at least two of four non-missing items tapping individual control over working conditions. The items were: (1) "I have the freedom to decide what I do on my job;" (2) "It is basically my own responsibility to decide how my job gets done; (3) "I have a lot of say about what happens on my job;" and (4) "I decide when I take breaks." Individual items were scored on a five-point Likert scale (with "don’t know" responses coded in the middle of the range); higher scale scores indicate more autonomy on the job (alpha = 0.73).

Missing data on wives’ work schedules in 1997 precluded the control for non-overlapping work schedules between respondents and their wives, a factor that is positively related to men’s participation in family life (Presser 2003).

Self-employed respondents had missing data on the measures of job autonomy, firm size, promotion expectations, and concerns about layoffs. Rather than deleting these measures from the analytic models or limiting the sample to wage and salary workers, self employed respondents were recoded to the maximum value for job autonomy, scored 0 on the dummy measures for large firm size and concerned about layoffs, and scored 1 on the dummy measure for expecting a promotion. The binary control for self-employment status controlled for these assignments.

Unexpectedly, worries about losing one’s job has a significant positive effect on non-workday time with children in 1977, but is not significant in 1997. It is possible that in 1977, men who are worried about their jobs attempted to soothe their children’s anxieties by spending more time with them on non-workdays, but as job instability became more widespread by 1997, this covariate no longer predicted non-workday time with children (Galinsky 1999; Townsend 2002). Similarly, working at home has the expected negative effect on workday and non-workday time with children in 1977, but as the incidence of working at home increased over time (i.e., the 1997 mean significantly exceeds the 1977 mean), its effect of shared time with children weakened significantly by 1997.

Readers might wish to see the contributions of individual slopes and the constants to explaining the temporal increase in child-care time investments. But, the magnitude of slopes and constants can vary greatly by measurement choices for predictor variables, yet the sum of these factors is fixed. For that reason, Jones and Kelley (1984) recommend summing the change in slopes and constants into a single component that taps overall change in behavioral propensities (see also Sayer et al. 2004).

References

Bianchi, S. M. (2000). Maternal employment and time with children: Dramatic change or surprising continuity? Demography, 37, 401–414.

Bianchi, S. M., Robinson, J. P., & Milkie, M. A. (2006). Changing rhythms of American family life. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Bond, J. T., Galinsky, E., & Swanberg, J. E. (1998). The 1997 national study of the changing workforce. New York: Families and Work Institute.

Brewster, K. L., & Padavic, I. (2000). Change in gender-ideology, 1977–1996: The contributions of intrachohort change and population turnover. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 477–487.

Bryant, W. K., & Zick, C. D. (1996a). An examination of parent-child shared time. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58, 227–237.

Bryant, W. K., & Zick, C. D. (1996b). Are we investing less in the next generation? Historical trends in time spent caring for children. Journal of Family and Econcomic Issues, 17, 365–392.

Budig, M. J., & England, P. (2001). The wage penalty for motherhood. American Sociological Review, 66, 204–225.

Bulanda, R. E. (2004). Paternal involvement with children: The influence of gender ideologies. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 66, 40–45.

Coltrane, S. (2000). Research on household labor: Modeling and measuring the social embeddedness of routine family work. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 1208–1233.

Craig, L. (2007). How employed mothers in Australia find time for both market work and children. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 28, 69–87.

Dermott, E. (2008). Intimate fatherhood: A sociological analysis. London: Routledge.

Estes, S. B., Noonan, M., & Maume, D. J. (2007). Is work-family policy use related to the gendered division of housework? Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 28, 527–545.

Fried, M. (1998). Taking time: Parental leave policy and corporate culture. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Galinsky, E. (1999). Ask the children. New York: Quill.

Gerson, K. (1993). No man’s land: Men’s changing commitments to family and work. New York: Basic Books.

Golden, L. (2008). Limited access: Disparities in flexible work schedules and work-at-home. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 29, 86–109.

Gornick, J. C., & Meyers, M. (2003). Families that work: Policies for reconciling parenthood and employment. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Greenstein, T. N. (1996). Gender ideology and perceptions of the fairness of the division of household labor: Effects on marital quality. Social Forces, 74, 1029–1042.

Hakim, C. (2002). Lifestyle preferences as determinants of women’s differentiated labor market careers. Work and Occupations, 29, 428–459.

Hall, S. S. (2005). Change in paternal involvement from 1977 to 1997: A cohort analysis. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 34, 127–139.

Hays, S. (1996). The cultural contradictions of motherhood. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Hochschild, A. (1989). The second shift. New York: Viking.

Hochschild, A. (1997). The time bind: When work becomes home and home becomes work. New York: Metropolitan.

Hofferth, S. L. (2003). Race/Ethnic differences in father involvement in two-parent families: Culture, context, or economy? Journal of Family Issues, 24, 185–216.

Hofferth, S. L., Forry, N. D., & Peters, H. E. (2010). Child support, father–child contact, and preteens’ involvement with nonresidential fathers: Racial/ethnic differences. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 31, 14–32.

Jacobs, J. A., & Gerson, K. (2004). The time divide: Work, family, and gender inequality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Jones, F. L., & Kelley, J. (1984). Decomposing differences between groups: A cautionary note on measuring discrimination. Sociological Methods and Research, 12, 323–342.

Lareau, A. (2002). Invisible inequality: Social class and childrearing in black families and white families. American Sociological Review, 67, 747–776.

LaRossa, R. (1997). The modernization of fatherhood: A social and political history. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Maume, D. J., & Bellas, M. L. (2001). The overworked American or the time bind? Assessing competing explanations for time spent in paid labor. American Behavioral Scientist, 44, 1137–1156.

Maume, D. J., Sebastian, R. A., & Bardo, A. R. (2009). Gender differences in sleep disruption among retail food workers. American Sociological Review, 74, 989–1007.

Monna, B., & Gauthier, A. (2008). A review of the literature on the social and economic determinants of parental time. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 29, 634–653.

Nock, S. L., & Kingston, P. W. (1988). Time with children: The impact of couples’ work-time commitments. Social Forces, 67, 59–85.

Pleck, J. H. (2004). Paternal involvement: Levels, sources, and consequences. In J. H. Pleck & B. P. Masciadrelli (Eds.), The role of father in child development (4th ed., pp. 221–271). New York: Wiley.

Presser, H. (2003). Working in a 24/7 economy: Challengers for American families. New York: Russell Sage.

Risman, B. J. (1987). Intimate relationships from a microstructural perspective: Mothering men. Gender and Society, 1, 6–32.

Ryder, N. (1960). The cohort as a concept in the study of social change. American Sociological Review, 23, 843–861.

Sandberg, J. F., & Hofferth, S. L. (2001). Changes in children’s time with parents: United States, 1981–1997. Demography, 38, 423–436.

Sayer, L. C., Bianchi, S. M., & Robinson, J. P. (2004). Are parents investing less in children? Trends in mothers’ and fathers’ time with children. American Journal of Sociology, 110, 1–43.

Staines, G. L., & Quinn, R. P. (1979). American workers evaluate the quality of their jobs. Monthly Labor Review, 102, 3–12.

Townsend, N. W. (2002). The package deal: Marriage, work, and fatherhood in men’s lives. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Waldron, I., Weiss, C. C., & Hughes, M. E. (1998). Interacting effects of multiple roles on women’s health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 39, 216–236.

Williams, J. (2000). Unbending gender: Why family and work conflict and what to do about it. New York: Oxford University Press.

Yeung, W. J., Sandberg, J. F., Davis-Kean, P. E., & Hofferth, S. L. (2001). Children’s time with fathers in intact families. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 63, 136–154.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R03-HD42411-01A1), and the Charles Phelps Taft Research Center at the University of Cincinnati. I thankfully acknowledge the comments of participants in the workshop series at the University of Chicago’s Sloan Center for Parents, Children, and Work, and the colloquium series at the University of Cincinnati.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Maume, D.J. Reconsidering the Temporal Increase in Fathers’ Time with Children. J Fam Econ Iss 32, 411–423 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-010-9227-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-010-9227-y