Abstract

In this essay, we discuss how the COVID-19 pandemic drove key changes in schooling and what forces can sustain these changes. Responding to the argument that COVID-19-driven changes may not be sustainable, this essay offers a counter narrative from the Korean context, in which educators re-visited existing school systems and re-constructed policies and teaching practices to fill the educational vacuum caused by the pandemic. This essay specifically builds on interviews conducted with Korean educators throughout the 2020 school year during COVID-19. First, we discuss ownership of educational change as reflected in educators’ narratives. We then explore three driving forces behind the transformation of the “grammar of Korean schooling”: policy discourse about “future education,” professional teaching culture, and administration for creativity. Based on our analysis, we offer several suggestions for policymakers, district leaders, and educators around the world for how to leverage and sustain the educational changes catalyzed by COVID-19. We conclude by arguing that educators’ desires to achieve change must be actualized in schools and policies through collaborative foresight and system-level support.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has altered multiple aspects of everyday life, especially those requiring personal interactions and daily routines. As a result, the core practices of things like schooling and student learning have had to be fundamentally revised. Schools across the world have thus adopted policies and practices to facilitate virtual learning, which have forced educators to quickly learn how to design and enact online lessons with limited resources (United Nations, 2020). Schools have invented and established these routines as the “new normal,” all while navigating a persistent level of uncertainty. Although COVID-19 has highlighted and exacerbated the digital divide as well as social inequalities like economic and racial injustice (United Nations, 2020), scholars and educators have argued that this disruption also presents an opportunity for the equitable redesign of school systems (Zhao, 2020). With massive vaccination efforts, schools are now preparing to go back to “normalcy” for post-COVID-19 education (see Durston et al., 2021; Meckler & George, 2021). In reflecting on the many innovations schools have made during COVID-19 (e.g., online and blended learning, individualized support), it is important to consider Zhao and Watterston’s (2021) argument that the educational changes imposed by the pandemic may be unsustainable for the long-term.

While superficial changes in schooling made during the pandemic may not be sustainable, this essay offers a counter-narrative from the Korean context, in which educators re-constructed policies and teaching practices to fill the educational vacuum caused by COVID-19. The lessons we address here build on 23 Zoom interviews (including 17 individual interviews and six focus groups) conducted throughout the 2020 school year with Korean teachers, school and district leaders, and parents across the country. As education researchers residing in the US during the pandemic who previously worked as Korean school teachers, we wanted to present stories of how Korean schools implemented online and hybrid classes without large-scale school closures and how educators made meaning of the changes forced by COVID-19.

What was most striking to us was the ownership of educational change reflected in the educators’ narratives. This sense of ownership can be understood as a “mental or psychological state of feeling owner of an innovation” that enables educators to understand how changes are applied and their specific roles in initiating these changes (Ketelaar et al., 2012, p. 5). In navigating and reflecting on the pandemic’s unexpected challenges, they placed themselves at the center of efforts to realize “future education.” Teachers and leaders thereby perceived educational innovations as both a short-term reaction to the pandemic and as sustainable transformations to lead in the long run. This sentiment was apparent in their responses to the sudden onset of COVID-19, as well as in their approach to schooling a year into the pandemic. For the Korean educators we interviewed, “back to school” does not mean back to pre-pandemic schooling of the past. Although we do not generalize their responses as “the Korean case,” our surveys of news articles, books, and online teacher communities in Korea indicate strong aspiration for changes stemming from critiques of pre-pandemic education.

Behind the ownership of sustainable changes: Three driving forces

Throughout the research process, we consistently asked what led the Korean educator participants to take ownership of school changes. As an irresistible force (Stone-Johnson, 2021), COVID-19 has imbued education communities with a sense of urgency and purpose to collectively revise school systems. One teacher participant explained that educators were dragged into “a situation where we’re [teachers] making something new from nothing.” To fill the vacuum of structures and daily practices created by the crisis, school constituents had to collaborate to “create something” to help students learn. For instance, one teacher association representative who worked closely with the Ministry of Education (MOE, hereafter), expressed that these initiatives eventually led to changes in the “old grammar of Korean education,” which he described as heavily focused on college preparation, competition-driven learning, and bureaucratic school culture. We found the disruption of these conditions by COVID-19 required educators to research and reconstruct new values, such as “individualized student needs,” “democratic schooling,” and “learning focused professional culture,” to replace the old grammar of schooling (Tyack & Tobin, 1994). Our interviewees’ responses also affirm the emergence of collective contemplation regarding “future education” through policy agendas, research initiatives, and daily news outlets.

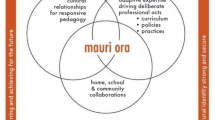

Echoing the argument that COVID-19 catalyzed the realization of school reforms (Kim et al., in press), we identified three macro-level driving forces in participants’ stories that enabled transformations in Korean schools: policy discourse about “future education,” professional teaching cultures, and using bureaucratic administration creatively.

Policy discourse about “future education”

In the Korean context, the discourse of “future education” driven by the MOE during COVID-19 was critical in orienting multiple policy actors to navigate the new and uncertain policy environment. The slogan of “future education” in Korea, a widely spread discourse in multiple policy initiatives during the pandemic, was not a new idea. For instance, at the global level, international organizations have highlighted new ways of thinking for the “Future of Education,” including paradigm shifts, 21st-century skills, digital revolution, and curricular redesign (e.g., OECD, 2013; UNESCO, 2019), and the Korean government has adopted many of these global discourses in their national policy agendas (Howells, 2018). When COVID-19 made education transformation urgent, policymakers at the top effectively utilized the discourse of “future education” as a rationale for educators’ prompt shift in instruction to online platforms. Therefore, although the MOE had already invested time and resources in classroom technologies and online instruction in the past decade, the pandemic further opened a window of opportunity (Kingdon, 2010) for educators across the country to implement online teaching.

The MOE’s active spread of the “future education” discourse through multiple initiatives drove and, to some extent, forced policy actors on the ground to make innovations using available digital infrastructures and online teaching skills (Ministry of Education, 2020a). For example, the MOE strategically used the media as a key tool for publicizing major policy decisions while disseminating new school guidelines through local districts (Kim et al., in press). The use of media in this way facilitated sensegiving in the policy process (Maitlis & Lawrence, 2007) and was helpful in framing the urgent changes caused by the pandemic. Although teachers were unexpectedly forced to teach online, the idea of engaging methods of “future education” led them to accept this enforced change in the name of preparing students for their futures. While resistance to change is a prevalent phenomenon in teaching (Lortie, 1975), the Korean case shows that coalition between policymakers’ engagement with “future education” discourse and policy actors’ sense of urgency regarding the crisis provided the necessary momentum for promoting and retaining educational changes.

More surprisingly, the discourse of “future education” evolved to sustain itself as multiple policy actors constructed and enacted new education strategies via collective reflection on the needs of future education. We found that multiple policy actors, including researchers, educational leaders, teachers, and professional organizations, actively generated and fostered these ideas about future education in their own settings throughout the 2020 school year. Specifically, they identified what had been missing in the existing model of Korean education—i.e., support for students’ individual needs, efforts to narrow equity gaps exacerbated by COVID-19, and school-level authority for self-governance (Kim et al., in press). In doing so, educators imagined and implemented new practices for post-pandemic education and demonstrated that the pre-pandemic grammar of schooling could be productively altered for greater equity. They strongly believed education could be continuously developed as a long-term enterprise with collective visions and values, even after the end of COVID-19. Our observations of the Korean context imply that the effective use of policy discourse by upper-level policymakers can help schools achieve systematic changes (Spillane et al., 2002). The stories shared with us showed this process included the provision of consistent messages and a shared space wherein diverse policy actors could reflect on policy purposes and generate their own ideas.

Professional teaching culture

Another fundamental change in Korean schools during COVID-19 occurred in professional teaching culture, wherein Korean teachers collaboratively construct professionalism as educators. In general, teaching cultures guide teachers in establishing and strengthening the beliefs, values, and norms that make policy-initiated changes possible in daily school practices (Fullan, 1996; Kim & Reichmuth, 2021). The emphasis on collaboration in teacher communities is specifically essential to sustainable change because ideas can circulate and last beyond any one individual teacher (Hargreaves & O’Connor, 2018a). Our interviews with Korean educators suggest a shared sense of professionalism in teaching culture facilitated collaborative learning among teachers and promoted Korean educators’ ownership in leading educational changes during the pandemic.

Indeed, Korea has long invested in systems that support teachers’ collaborative development through both national and local policies (Kim et al., in press; OECD, 2020; Park & Byun, 2015). For instance, the government’s human resource policy requires teachers and administrators to rotate schools within a given region every four to six years to ensure equitable teacher quality across schools for all students. This has helped teachers establish networks and professional cultures beyond their individual schools. These structures have been helpful in developing solidarity and solidity (Hargreaves & O’Connor, 2018b) among Korean teachers. Furthermore, the country’s social and historical background of valuing teaching have shaped conceptions of teachers as highly regarded professionals and teaching jobs as long-term careers (Kang & Hong, 2008; Kim & Han, 2002; NCEE, 2021). Together these shared notions have been an engine for sustaining and strengthening collaborative professionalism within the teaching culture in Korea.

At the height of the pandemic, this culture drove Korean teachers’ collaborative learning and creation of new knowledge in response to challenges. Teachers intensively learned skills for virtual instruction through online and in-person teacher networks outside schools as well as through professional learning communities within schools. When describing the pressures of the immediate implementation of online classes, one educator expressed that all educators were in the “same boat” and what they needed was a sense of shared responsibility, or “a sense of community to address challenges together.” Ironically, the teachers we interviewed noted that the online instruction forced by COVID-19 offered them key opportunities to learn from each other and make shared decisions. Without this established culture of support, schools across the country might not have been able to implement online classes with only a month of preparation.

At the system level, the MOE and local districts have backed solidarity among teachers through the provision of systematic supports, such as suspending teacher evaluations, financial support for teacher development, and resources for professional learning communities (NCEE, 2021). This culture of professionalism offered the foundation necessary for making sustainable changes during COVID-19. Of course, not all schools and teachers successfully implemented online and hybrid classes, but professional culture in Korean teaching society allowed space for collaboratively discussing which methods worked, which did not, and why. Teachers were thus able to share evidence from their experiences in both schools and districts that led them to learn from one another beyond their own schools. In this way, the shared norms and vision of Korea’s teaching culture significantly helped build and shape educators’ sense of ownership in making, leading, and sustaining changes in schools (Saunders et al., 2017).

Administration for organizational creativity

The Korean case suggests that bureaucratic systems can effectively support organizational creativity in response to crises when accompanied by close communication and resources. Compared to countries with decentralized or market-based school systems, the central government and MOE in Korea have primarily driven the development of education policy through a highly developed bureaucratic system (Kim, 2020) despite efforts to decentralize school operations for the last three decades (e.g., local and school level curricula, direct elections for superintendents at the municipal level, democratic decision-making in schools) to meet and support local needs (Jeong et al., 2017). In this context, we found bureaucratic structures functioned to implement policy decisions in rapidly changing circumstances, such as those induced by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our interviews with Korean educators and leaders suggest this bureaucratic system can support and sustain systematic changes when relevant resources and flexibility are provided to local schools. While Weber (1968) has argued bureaucracy to be the most technically efficient form of modern organization because it promotes speed, accuracy, clarity, and knowledge accumulation, such impediments can be seen as red tape in systems that do not offer individuals what they need (Labaree, 2020). We acknowledge these aspects of bureaucracy as a double-edged sword. Yet, we also argue that, during the unprecedented COVID-19 crisis, the timely delivery of guidelines and resources to local schools relied on the efficiency of Korea’s bureaucratic administration to prevent infections and implement online classes (Kim et al., in press). The MOE used centralized guidelines to continue to support autonomy and professional discretion in schools, which allowed each school to adopt various approaches based on their local needs. At the municipal level, the MOE and Offices of Education lifted restrictions in existing policies related to human resources, curriculum, and budget to increase flexibility in school-level decisions. Moreover, the MOE provided public IT infrastructure, online learning resources, and guidelines for schools on how to implement new educational activities (Ministry of Education, 2020b).

The use of close communication within this hierarchical administrative system was critical to the collection and distribution of information that ultimately promoted successful policy decisions (Kim et al., in press). We found that, during the pandemic, districts and schools actively utilized (in)formal networks both vertically (e.g., between the MOE and schools) and horizontally in virtual settings. To cope with the uncertainty and lack of knowledge about COVID-19, organizations turned to smartphone messenger apps and video calls in professional work settings instead of mainly relying on official chain of command (Song, 2020). For example, policymakers at the upper levels used smartphone messenger apps instead of official documents or emails to conduct multiple surveys and listen to local voices (Ministry of Education, 2020a). Local districts further utilized an anonymous group chat wherein teachers could express complaints and opinions so that district officials could deliver teachers’ needs to the MOE. Moreover, it was typical for educators to use multiple group chats to communicate with their grade teams, subject groups, and leadership teams across the region to collect information for making informed decisions at the school level. Combined with Korea’s highly developed bureaucracy, this kind of technology driven communication fostered timely and speedy communication among education professionals and institutions. It also helped overcome the rigidness of bureaucratic structure and stoked creativity in the development of policies under the crisis (Ansell & Boin, 2019). Overall, this enabled individuals at the local level to understand and quickly implement macro-level policy decisions that reflected their local needs.

Lessons learned: Suggestions for back to school with COVID-19

The urgency of the COVID-19 crisis required policymakers and educators around the globe to reimagine and transform school education. Stories of the Korean case show that while educators encountered unprecedented challenges, the pandemic allowed them to take ownership in creating and leading relevant changes in school settings. In doing so, teachers and education leaders have continued to reflect on these ongoing changes to actualize more effective ways of schooling during and beyond COVID-19. By asking what educators did to take ownership of educational changes, we identified a widely shared policy discourse of “future education,” collaborative professionalism in Korean teaching culture, and administrative systems that supported organizational creativity as macro-level driving forces. Based on participants’ stories, we offer several suggestions for policymakers, district leaders, and educators around the world for how to more leverage and sustain the educational changes catalyzed by COVID-19.

Policymakers: Seize policy window for large-scale changes

Policymakers must realize that educators and school leaders on the ground are likely to resist or distort policy goals when feeling uncertainty and threat, even when policies are carefully designed (Evans, 1996). While COVID-19 increased the level of uncertainty in policy decisions and messages, the sense of urgency from the pandemic also opened a window of opportunity for policymakers to implement system-wide reforms (Kingdon, 2010). It is thus important for policymakers seeking sustainable change to effectively utilize this opportunity to realize large-scale changes they and others have been longing for.

Create and spread consistent policy messages

The Korean case illustrates that policymakers must provide consistent messaging while prioritizing students’ and educators’ safety and welfare during crisis. Although policy environments fluctuated as the virus spread and political controversies took hold in the wider society, policymakers should take care to maintain consistency and regularity in communication. First, policymakers should follow health professionals’ guidelines for prioritizing the safety and well-being of each individual and community. In Korea, people’s lives were top priority throughout the policy process, which enabled them to share values and cooperate with new guidelines. With shared values, policymakers can maintain continuity by linking newly adopted COVID-19 policy mandates to existing policy efforts. For example, the sudden shift to online and hybrid schooling caused chaos in schools and student families, but Korean policymakers successfully linked these forced sudden changes to the discourse of “future education” from existing initiatives for national curriculum reform. In addition, consistency was achieved via the process of active sensegiving with the use of technology-driven communications. As COVID-19 forced individuals to rely on online-based communications (e.g., video conferences), policymakers can use multi-directional communication tools with traditional media to generate and disseminate policy messages in response to crises.

Offer a shared space for diverse policy actors

A shared space for diverse policy actors—including teachers, leaders, students, and families—helps actors reflect on policy purposes and generate their own ideas. Policymakers must thus continue asking: What challenges need to be addressed? What resources are needed for schools? Do the current policies really help people on the ground and student learning? Doing so enables policymakers to utilize educators’ prior beliefs, knowledge, and practices as key drivers of successful policy implementation with a message of supplementing educators’ work rather than supplanting it (McLaughlin, 1987; Spillane et al., 2002). As an ongoing reciprocal process, policy development needs to be done at multiple levels, including schools, districts, and states, by engaging a wide range of individuals impacted by the policy. Policymakers can offer flexibility in implementation processes so policy actors can engage new meanings, adaptations, and narratives regarding the needs of their own schools (Maitlis & Lawrence, 2007). Throughout such a process, policymakers would support educators in becoming active agents who can positively adopt changes imposed by the pandemic that revise old systems of schooling.

District leaders: Utilize bureaucracy as resources for local needs

The Korean case reconfirms that policy discourse and professional culture can be achieved through highly developed bureaucracy if local needs are prioritized via technical efficiency and organizational creativity. COVID-19 ironically imposed bureaucratic shifts away from adhocracy towards a network governance. Therefore, to implement and sustain systemic changes, administration systems must offer relevant resources attuned to local needs and timely communication for effective decision-making and operationalization of goals and practices on a large scale (Hubers, 2020). During the pandemic, district leaders were required to tap into creativity and flexibility beyond the rigidity of administration to collect and disseminate accurate information, create timely resources, and share knowledge for schools and local communities. In other words, system-wide change can be achieved during and after COVID-19 depending on how district leaders creatively organize and use bureaucratic structures.

Adopt hybrid governance to coordinate resources

We advise districts play the role of a hub that coordinates all available information and policy resources for local schools and communities by utilizing existing bureaucratic systems as infrastructure. The pandemic forced different divisions of governmental and public organizations to cooperate at both the national and global levels, which influenced all aspects of people’s social lives, including schooling. District administrators are now tasked with collecting new information on health guidelines, education policies, and social welfare resources from their local government offices and health department, as well as the Ministry of Education. This hybrid form of governance—i.e., utilizing networks and the hierarchal chain of the bureaucracy—can promote efficiency in knowledge accumulation and coordinating policy resources (Kim, 2020). With this form of governance, district leaders can actively hear voices of educators in schools and local communities to know what resources are needed for them.

With the rise in online and hybrid classes, COVID-19 has created opportunities for districts to better utilize technology-based communications for making democratic decisions in a timelier manner. For example, Korean districts created interactive online forums wherein communities were invited to share their experiences, use smartphone app chat rooms for exchanging instant messages, and discuss financial and human resources with one another. These open approaches to communication can increase democratic engagement from local schools and communities toward the shared goal of supporting student learning. District leaders need to effectively utilize centralization as an enabling factor to accumulate and spread knowledge and innovation. For instance, Korean district leaders shared successful and unsuccessful strategies horizontally with other districts and lessons were further shared with multiple Offices of Education at the municipal level and the Ministry of Education. In this way, the accumulated knowledge at the top of the system was successfully shared with local schools across the country. This demonstrated that centralization, one of the key characteristics of bureaucracy, can facilitate knowledge creation and dissemination during crises like the pandemic. Given this, information transparency, technology-based communication that allows for timely responses, and organizational creativity utilizing bureaucratic structures can be critical for quickly and effectively addressing sudden mass changes.

Reorganize bureaucracy to serve educators as professionals

Districts can additionally reframe and reorganize bureaucratic structures to promote collaborative foresight and system-level support for sustainable changes in schools. As the COVID-19 pandemic has lasted beyond the span of a single school year, educators are continuing to realize that old grammar of schooling is incompatible with the “new normal.” This realization has pushed them to equip themselves with new competencies, such as skills for online and/or blended teaching, addressing students’ individualized needs, equity minded teaching, as well as collaborative curriculum development and teaching. Districts must therefore support teachers’ desires to achieve change through collective efforts by solidifying systemic supports and policies (Hargreaves & O’Connor, 2018b). Districts can, for instance, create professional networks at the district level for teachers to collaborate and learn from each other across schools. Moreover, teacher learning should be rewarded with financial and human resources that support collaborative professionalism because teachers and school leaders have been the drivers of meaningful policy changes that continue to make student learning during the pandemic possible. As such, bureaucracy should not be a fixed code, rule, or chain of commands—rather, it should be supportive in providing resources that prioritize educators’ development of professional insights that lead to new ideas and more equitable systems.

School leaders and teachers: Prioritize equity and care through professional teaching culture

Schooling during COVID-19 placed teachers and school leaders at the center of crisis management for student learning. This resulted in broader understandings of students’ needs as COVID-19 underscored existing inequities in social systems. More than ever before, school leaders and teachers have been critically reflecting on and reconceptualizing the role of schooling in student learning. To leverage these opportunities, we contend educators must shape professional teaching culture to prioritize equity and care for students and teachers toward the production of quality learning.

Develop culture of equity-minded teaching and learning

Like other educators across the world, the Korean educators in our study realized that a one-size-fits-all model of education does not work for student engagement and meaningful learning. They especially found that virtual learning spaces require more effort to identify and address students’ unique needs, all of which are closely associated with their families’ socio-economic situations. While policymakers and district leaders offer resources for schools and local communities, teachers and school leaders need to be cognizant regarding matters of access and equity in education systems because they are the ones directly engaging with students. Without meeting the needs of student well-being, teachers cannot effectively nor meaningfully support students. In other words, we argue teacher professionalism should prioritize and centers equity and care.

The Korean teachers and leaders in our study sought new roles for themselves during and beyond the pandemic that included the provision of additional care for students from economically disadvantaged homes, developing individualized mentoring time for students beyond regular work hours, and engaging with local communities. While the level of commitment varied depending on each individual, we advise that teachers and leaders establish a collective norm and culture centered on equity driven approaches to teaching and guiding students through professional learning communities. When issues of inequality are addressed beyond an individual level, schools can ensure equity in teaching and thereby ensure quality in student learning.

Balance commitments to others and self-care

Indeed, the pandemic forced educators to embrace additional commitments to their students and vulnerable adults. In doing so, they showed these commitments were paramount to overcoming a crisis as devastating and far-reaching as COVID-19. At the same time, we acknowledge many school leaders and teachers in Korea and other countries have been experiencing burnout and emotional difficulties under the pressure of meeting the needs of others. Their work environments impose long hours of working in virtual spaces and their in-person interactions require risking infection and mental fatigue. Furthermore, social distancing led to distance in the emotional and relational aspects of their daily work. Prioritizing the well-being of students and local communities over an educator’s own self-care can and has depleted the well-being of school leaders and teachers. Many of Korean teachers in our study explained that they kept away from family and social gatherings for a year to protect the students and colleagues they worked with. As the pandemic endures, it is important for school leaders and teachers to achieve balance in their commitments to others and to themselves if they are to effectively and healthily continue their jobs. We believe school leaders can shape school culture to support teachers balancing these demands, and that they can help encourage the establishment of collective resources toward this end. Doing so, we hold, can better support meaningful learning for students.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has shaken the structure and practices of education systems around the world. It forced schools to change their core activities from the bottom up and create new ideas and systems to support student learning. Schooling during the pandemic has thus necessarily revealed challenges that must be addressed (e.g., widening achievement gaps), but it also surfaced opportunities for challenging the “old grammar of schooling” in how Korean educators took ownership of educational changes to collectively envision better ways of schooling during and after COVID-19. In reflecting on how to actualize these aspirations as sustainable changes in the post-COVID era, we offered implications for policymakers, district leaders, and educators based on what we identified as important factors that can lead individual-level changes to sustainable systematic changes—i.e., policy discourse, collaborative teaching culture, and using bureaucracy for organizational creativity. As diverse agents proceed in creating and leading educational changes initiated by the spread of COVID-19, we hope this essay and the stories shared by Korean educators here can offer opportunities for other educators to reflect on, take ownership of, and lead changes in schooling that benefit all students.

References

Ansell, C., & Boin, A. (2019). Taming deep uncertainty: The potential of pragmatist principles for understanding and improving strategic crisis management. Administration & Society, 51(7), 1079–1112.

Durston, E. A., Levin, D., & Kim, J. (2021). ‘I was so nervous’: Back to class after a year online. The New York Times. Retrieved April 30, 2021, from https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/09/us/schools-reopen-covid.html.

Evans, D. (1996). Before the roll call: Interest group lobbying and public policy outcomes in House committees. Political Research Quarterly, 49(2), 287–304.

Fullan, M. (1996). Professional culture and educational change. School Psychology Review, 25(4), 496–500.

Hargreaves, A., & O'Connor, M. T. (2018a). Leading collaborative professionalism. Centre for Strategic Education.

Hargreaves, A., & O’Connor, M. T. (2018b). Solidarity with solidity: The case for collaborative professionalism. Phi Delta Kappan, 100(1), 20–24.

Howells, K. (2018). The future of education and skills: Education 2030: The future we want. Working Paper. OECD. http://www.oecd.org/education/2030/E2030%20Position%20Paper%20(05.04.2018).pdf.

Hubers, M. D. (2020). In pursuit of sustainable educational change-Introduction to the special section. Teaching and Teacher Education, 93, 103084.

Jeong, D. W., Lee, H. J., & Cho, S. K. (2017). Education decentralization, school resources, and student outcomes in Korea. International Journal of Educational Development, 53, 12–27.

Kang, N. H., & Hong, M. (2008). Achieving excellence in teacher workforce and equity in learning opportunities in South Korea. Educational Researcher, 37(4), 200–207.

Ketelaar, E., Beijaard, D., Boshuizen, H. P., & Den Brok, P. J. (2012). Teachers’ positioning towards an educational innovation in the light of ownership, sense-making and agency. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(2), 273–282.

Kingdon, J. W. (2010). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies (2nd ed.). Longman.

Kim, E. G., & Han, Y. K. (2002). Attracting, developing and retaining effective teachers Background report for Korea. Korean Educational Development Institute.

Kim, T. (2020). Revisiting the governance narrative: The dynamics of developing national educational assessment policy in South Korea. Policy Futures in Education, 18(5), 574–596.

Kim, T., Lim, S., Yang, M., & Park, S. (in press). Making sense of schooling during COVID-19: Crisis as opportunity in Korean schools. Comparative Education Review.

Kim, T., & Reichmuth, H. L. (2021). Exploring cultural logic in becoming teacher: A collaborative autoethnography on transnational teaching and learning. Professional Development in Education, 47(2–3), 257–272.

Labaree, D. F. (2020). Two cheers for school bureaucracy. Phi Delta Kappan, 101(6), 53–56.

Lortie, D. C. (1975). Schoolteacher: A sociological study (2nd ed.). The University of Chicago Press.

Maitlis, S., & Lawrence, T. B. (2007). Triggers and enablers of sensegiving in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 57–84.

McLaughlin, M. W. (1987). Learning from experience: Lessons from policy implementation. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 9, 171–178.

Meckler, L., & George, D. (2021, April). Will school be back to normal this fall? Kind of, sort of, maybe. The Washington Post. Retrieved April 30, 2021, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/schools-fall-plans/2021/03/30/0fb982a8-8daf-11eb-a730-1b4ed9656258_story.html.

Ministry of Education (2020a). Responding to COVID-19: Online Classes in Korea. https://www.gcedclearinghouse.org/sites/default/files/resources/200292eng.pdf.

Ministry of Education (2020b). Proposal of 10 major policy tasks post COVID-19. https://www.moe.go.kr/boardCnts/view.do?boardID=294&lev=0&statusYN=W&s=moe&m=0204&opType=N&boardSeq=82145

National Center on Education and the Economy (NCEE). (2021). South Korea: Teacher and principal quality. Retrieved May 6, 2021, from https://ncee.org/center-on-international-education-benchmarking/top-performing-countries/south-korea-overview/south-korea-teacher-and-principal-quality/.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2013). Teachers for the 21st century: Using evaluation to improve teaching. Author

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2020). School education during COVID-19: Were teachers and students ready? https://www.oecd.org/education/Korea-coronavirus-education-country-note.pdf.

Park, H., & Byun, S. Y. (2015). Why some countries attract more high-ability young students to teaching: Cross-national comparisons of students’ expectation of becoming a teacher. Comparative Education Review, 59(3), 523–549.

Saunders, M., Alcantara, V., Cervantes, L., Del Razo, J., Lopez, R., & Perez, W. (2017). Getting to Teacher Ownership: How Schools Are Creating Meaningful Change. Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University.

Song, H. (2020, September). COVID-19 led to 40% increase in the video call time through Kakao Talk. News1. http://news1.kr/articles/?4064342.

Spillane, J. P., Reiser, B. J., & Reimer, T. (2002). Policy implementation and cognition: Reframing and refocusing implementation research. Review of Educational Research, 72(3), 387–431.

Stone-Johnson, C. (2021). Impact of Covid-19 on educational change: Back to school. Retrieved May 10, 2021, from https://www.springer.com/journal/10833/updates/18340814.

Tyack, D., & Tobin, W. (1994). The “grammar” of schooling: Why has it been so hard to change? American Educational Research Journal, 31(3), 453–479.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (2019). Futures of education: The initiative. https://en.unesco.org/futuresofeducation/initiative.

United Nations (2020, August). Policy Brief: Education during COVID-19 and beyond. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2020/08/sg_policy_brief_covid-19_and_education_august_2020.pdf.

Weber, M. (1968). Economy and society: An outline of interpretive sociology. Bedminster Press

Zhao, Y. (2020). COVID-19 as a catalyst for educational change. Prospects, 49(1), 29–33.

Zhao, Y., & Watterston, J. (2021). The changes we need: Education post COVID-19. Journal of Educational Change, 22, 3–12.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, T., Yang, M. & Lim, S. Owning educational change in Korean schools: three driving forces behind sustainable change. J Educ Change 22, 589–601 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-021-09442-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-021-09442-2