Abstract

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 disease (COVID-19) was first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, China, and was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on 11 March, 2020. Since then, physical distancing measures such as confinement have been adopted by different governments to control human to human transmission. This study aimed to determine how confinement affects children’s routines, more specifically their physical activity (PA) and sedentary time. An online survey was launched to assess how Portuguese children under 13 years of age adjusted their daily routines to confinement. Parents reported the time each child was engaged in different activities throughout the day, which was used to calculate overall sedentary time and overall physical activity time. Based on the data of 2159 children, our study showed that during confinement: (i) there was a decrease in children’s physical activity time and an increase in screen time and family activities; (ii) boys engaged in more playful screen Time than girls (p < 0.05), and girls played more without PA than boys (p < 0.05); (iii) along the age groups, there was a trend for an increase of the overall sedentary time and an associated decrease of the overall physical activity time. In summary, PA of confined children showed low levels and a clear decreasing trend along childhood. Conjoint family and societal strategies to target specific age groups should be organized in the future.

Highlights

-

This study aimed to analyze how confinement affected children’s physical activity (PA) and sedentary time, during the COVID-19 pandemic, in Portugal.

-

There was a decrease in children’s PA time, an increase in screen time, and family activities.

-

The only sex differences were found on playful screen time and in play without PA.

-

Along age groups, there was a trend for the increase of the overall sedentary time and an associated decrease of overall PA time.

-

Low levels of PA among children have psychological, social, physical, and overall health implications that might persist in the long term.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Since the first cases reported in the city of Wuhan, China, COVID-19 has spread across many countries infecting more than 40,269,921 people worldwide (Coronatracker 2020). Hong-Kong and Singapore’s previous experience in dealing with the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak, in 2002/2003, provided many lessons to other countries and showed the efficacy of timely quarantine and isolation measures (Giubilini et al. 2018; WHO 2003). Furthermore, the three weeks lockdown experience of China (Wuhan), which resulted in travel restrictions, home quarantine, social distancing and outside activities limited to 30 min every second day, were quite effective, reinforcing the idea that this kind of measures could help to contain the epidemic (WHO 2020; Lau et al. 2020). So, due to the highly contagious nature of this virus, and in the absence of effective treatments, enforcing social isolation and confinement was the best way to control the infection (Sun et al. 2020).

Most of the European affected countries enforced different measures to keep people at home, such as closing the entire school system, closing non-essential government and private services, and asking employees to work from home (Islam et al. 2020). Portugal responded quickly to the coming menace. The first case was reported on the last week of February 2020 and, on March 16, schools, companies, and non-essential public services were closed across the country. Two days later, the state of emergency was declared by the Portuguese President. Restrictions on circulation were imposed for the entire population, all shops were closed (except for supermarkets, pharmacies, and gas stations), and restaurants could only operate as take-away. Despite the benefit of preventing high rates of the virus transmission, being in quarantine is an unpleasant experience, since it gives a feeling of loss of freedom, boredom, and uncertainty over disease status, affecting one’s health status (Mattioli et al. 2020). During this time, people are likely to experience fear, helplessness, and stigma (Jeong et al. 2016), and with the closure of schools and businesses, such emotions can become exacerbated (Hall et al. 2008; Rubin et al. 2010).

Confinement brought a new paradigm to children’s lives. Children, who used to spend their days at school and playing outside, were suddenly confronted with a home-schooling program, locked in their homes. This signaled the beginning of a long period of movement restriction, with no organized physical activity (PA), no free playtime outdoors, and no opportunities to spend time with friends. School programs for primary-school children and most secondary-school children were transferred to a mixed system of broadcast television and on-line home schooling from April to June, and all sports/leisure activities were suspended until September. Although quick walks and outdoor playtime (20 min) were permitted during the confinement, all outside playgrounds were closed and children were encouraged to maintain social distance between themselves. The confinement period was quite effective in reducing the virus spread in Portugal, so a gradual lifting of the emergency measures led to the reopening of daycares on May 18, 2020, and preschools on June 1, 2020. However, many families with younger children whose parents were still working from home, decided that their children would only go back to school in September.

In non-quarantine conditions, measured data on PA shows that only 36% of Portuguese children aged 10–11 years accomplished the WHO PA guidelines of 60 min per day of moderate-to-vigorous PA (Baptista et al. 2012) and, although 61.8% of 6- to 9-year-old children and 59% of 10- to 17-year-old youths practice some form of organized sports at least once per week (Lopes et al. 2017), school has a major role in promoting PA habits in this population. In Portugal, Physical Education (PE) classes are mandatory for all students, from pre-school until the 12th grade. Time allocated to PE classes ranges from 90 to 150 min/week over 2 or 3 sessions/week and are taught by a certified PE teacher (Mota et al. 2018). Considering other PA habits of Portuguese children, some points deserve further consideration. Portugal has low levels of independent mobility (i.e., children’s freedom to get about and play in their neighborhood unaccompanied by adults), and screen time is popular among children and adolescents. For example, 76.6% of the children between 6- and 10-years old commute by car to school, and only 17.5% walk or cycle to school. On weekdays 22% of children spend more than 1 h a day watching TV or using electronic devices, and this percentage more than triples at weekends (79%) (Lopes et al. 2017). When compared to other countries, Portuguese children rank low in their levels of independent mobility. In a study with 16 countries published in 2015 (Shaw et al. 2015), Portugal ranked in 14th place, along with Italy and just before South Africa, as the countries with less independent mobility. More recently, results from the WHO Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative (COSI), which provide an overview of the PA habits of children in the WHO European Region, showed that Portuguese children were the ones with the lowest levels of active travel to school (Whiting et al. 2020). Conversely, although most Portuguese children spent about 1 h a day watching TV or using electronic devices, their levels of screen time involvement were not as high as in most other countries (Whiting et al. 2020).

The low values of children’s PA and the high values of sedentary behavior have a negative impact on their motor competence (Vandorpe et al. 2011), body composition, and cardiovascular fitness (Tomkinson and Olds 2007). PA provides significant health benefits, such as high bone density, high levels of motor competence, better physical fitness and a healthy weight. Besides, it promotes children’s mental health, psychosocial skills, academic performance (Biddle et al. 2004) and a more robust immune system (Lasselin et al. 2016), which is essential in the pandemic situation we live in.

This pandemic event has disrupted many aspects of the daily life of children and their families around the world. PA behaviors decreased (Moore et al. 2020; Pietrobelli et al. 2020), screen time increased (Carroll et al. 2020), and eating habits changed in most cases for the worst (Direção-Geral da Saúde 2020). But little is known about the motor behaviors of the Portuguese children through the weeks of confinement. We recently published data from a similar study (Pombo et al. 2020), which found that such as younger age, access to a large outdoor space, presence of other children in the household and at least one non-working adult at home, positively influenced the percentage of physical activity done by children during confinement. However, a more complete description of the Portuguese children’s routines during confinement has not yet been presented. This study fills that gap in the preceding literature, intending to describe the Portuguese children’s routines during confinement that is not presented in the previous article. Nowadays, we are seeing the acute effects of the confinement in children’s behaviors but, we still do not know what future will bring. In that sense, we feel that this description is fundamental, not only to understand the implications of this confinement in children’s health, but it can also lay the foundations for future studies in this field.

So, we aimed to understand how Portuguese families with children under 13 years old, faced the confinement period, mainly concerning their routines of physical activity, sedentary activity, intellectual activity, play, outdoor and screen time. We decided to focus on children under age 13 because even though families are always important in the upbringing of their children, in the younger ages the role of parents and families is fundamental. In fact, in Portugal the law recognizes this role and, for that reason, parents with children up to 12 years of age have specific privileges to give assistance to their children when needed.

We hypothesized that children would spend more time in sedentary, intellectual, and screen time behaviors than in PA, play, and outdoor time. Hence, we believe that studying the behavior of children during this period can help to understand how daily activity is impacted, supporting the selection of specific action strategies to minimize the negative effects of prolonged confinement.

Materials and Methods

The Survey

To assess how children under 13 years of age were dealing with confinement due to the COVID-19 situation, we created a survey on LimeSurvey, hosted by the Faculty of Human Kinetics, University of Lisbon. The survey was approved by the Faculty of Human Kinetics ethics committee. After a first validation of the questions by a group of five child development experts and a first pilot testing with 23 families, the survey was launched online on the 23rd March 2020 and advertised through social media (Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp), and by email. The survey—to be completed by the parent/adult responsible for the child(ren)—took approximately 5 min to complete the following 4 sections:

-

1.

Household (3 items, numerical input, and single choice questions): questions regarding the composition of the household and the number of children and adults who were at home, and how many were working from home.

-

2.

Housing characteristics (4 items, single choice questions): type and characteristics of the house (e.g., apartment or detached house; the number of rooms), existence or not of indoor space for physical activity (gym or exercise room) and outdoor space (no outdoor space, small outdoor space—up to 12 m2; large outdoor space—more than 12 m2).

-

3.

Household routines (6 items, Likert scale questions): questions about the level of concern regarding the situation of Covid-19 and the way routines were being adjusted (i.e., comparison between time spent in different activities before and after confinement).

-

4.

Children’s routines (16 items, single choice, and numerical input questions): questions related to child characterization (age, sex, PA before confinement, health status) and the time (reported in minutes) spent in different activities during the previous day.

Sample

The survey was completed with information provided by parents, regarding 2948 children under 13 years of age, during the second week and beginning of the third week of confinement (between March 23 and April 1). All respondents read the information about the study and gave their consent to the conditions by clicking to proceed on the first page of the survey. Withdraw from the survey could occur at any time by not proceeding or not submitting the survey at the end. After cleaning the database for missing or obvious wrong information (e.g., more than 24 h reported in a day, or no sleep time reported for children; n = 789 total), information regarding 2159 children under 13 (1.117 boys and 1.042 girls) was considered in this study.

Statistical Analysis

The analysis of the results was based on answers relative to a total of 2159 children. Children were divided into four age groups according to the school levels in Portugal, which respect the different stages of children’s development (infancy and toddlerhood, group 1 = 0–2 years; n = 462, early childhood, group 2 = 3–5 years, n = 765; childhood, group 3 = 6–9 years, n = 606 and pre-adolescence, group 4 = 10–12 years, n = 326). A priori power analysis was conducted using G∗Power3 (Faul et al. 2007) to test the difference between four independent group means using a two-tailed test, a medium effect size (d = 0.50), and an alpha of 0.05. The result showed that a sample of 74 participants was required to achieve a power of 0.80.

Descriptive statistics and frequency analysis were used to describe children’s living environments and routines during this period. Five categories of activities were analysed: intellectual activity (school assignments and online classes); playful screen time (games, movies, social networks, internet, audio, and video calls); play without physical activity (reading, drawing, painting, board games, cards, Legos, etc.); play with physical activity (hide and seek, jumping, running, etc.); physical activity (organized physical activity indoors, physical activity outdoors, walking the dog). The first three categories (intellectual activity, playful screen time, and play without physical activity) were added to calculate overall sedentary time, and the last two categories (play with physical activity and physical activity) were added to calculate overall physical activity time.

Separate 4 × 2 ANOVAs (age group by sex) were performed to investigate how the different activities and routines of the confined children were being organized according to children’s age and sex.

Results

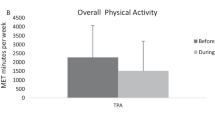

Although most children lived in apartments (60.3%), without any outside space (26.4% of the households) or with small outdoor spaces up to 12 m2 (37.6%), and 80.8% did not have a space dedicated to physical exercise (gym or exercise room) a relevant number of parents (44.8%) reported that it was easy to be in isolation with their children. Families acknowledged having changed their routines, more specifically the family schedule organization during the social confinement. Even though family activities have increased, most parents reported a decrease in the level of their children’s PA and an increased in screen time and sleep (Fig. 1).

The effect of age and sex on time spent by the children in the different groups of activities performed during the day are presented in Table 1 and Fig. 2.

As reported above, all categories presented main effects of age groups, although with different trends depending on age groups. For intellectual activity and playful screen time, we found that, as children get older, they significantly spent more time in these activities than the younger ones. Boys from the two older groups (6–12 years old) engaged more in playful screen time than girls.

Children in the 0-to-2 age group showed low involvement in both playtime categories (Play with PA and Play without PA), and 3- to-5-year-old children were the most engaged in playtime. Older age groups showed a steady significant decrease in both categories of Play after the age of 5. Girls older than 2 years of age engaged more in Play without PA than boys.

Regarding time spent in PA during confinement, we can see that all childhood groups (from 3 to 12 years old) showed similar values, whereas the 0-to-2 age group had significantly lower values of PA time.

For a better understanding of the relative importance of each of the five categories of activities in the child’s day for the different age groups, the time spent in each activity was converted into percentage, considering the total time reported for all categories. Overall physical activity and sedentary time were also calculated (Fig. 3).

The mean percentage analysis (Fig. 3) showed that intellectual activity and playful screen Time increased across the age groups, while the opposite trend occurred for all other categories. Play without Physical Activity was predominant in the two younger age groups. The 6 to 9-year-old age group showed higher values on playful screen time and the older age group shown higher intellectual activity.

When categories were grouped on overall physical activity (sum of physical activity and play with physical activity), and overall sedentary time (sum of intellectual activity, playful screen time, and play without physical activity), the results evidenced a decrease in the overall physical activity percentage and an associated increase in sedentary time day allocation as children’s age increases.

Discussion

With this study, we aimed to assess the immediate changes in PA and sedentary behaviors, in school-aged Portuguese children during the confinement period of the COVID-19 pandemic. Confirming the hypotheses that this type of restrictions are adverse to children movement behaviors (Guan et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2020), we found that during confinement Portuguese children were less active, more sedentary, more engaged in recreational screen-based activities, and spending more time sleeping when compared to the pre-confinement period.

The increase in sedentary behaviors and screen time, alongside the decrease of PA, is a serious concern. In school-aged children, sedentary behavior has been associated with inadequate body composition, decreased fitness, lower self-esteem and pro-social behavior, and decreased academic achievement (Tremblay et al. 2017). Reduced PA during childhood also hast long-term implications. As a child ages, the relationship between PA and motor competence (MC) becomes more reciprocal. Higher levels of MC foster more PA and, reciprocally, more PA fosters greater MC, this creates a positive spiral of engagement in PA across childhood, into adolescence bringing the healthy habits to adulthood (Stodden et al., 2008).

Reducing children’s sedentary behavior is an important goal, not only for the prevention and treatment of childhood (Epstein et al. 2000), but also to help to satisfy some of the children’s basic psychological needs, like social connected-ness, self-acceptance, and purpose in life (Rodriguez-Ayllon et al. 2019).

In Portugal, school provides a fundamental environment to achieve PA guidelines, mainly due to three reasons. First, physical education is mandatory, although school offer varies regarding the number of hours children have PE during the week (from 90 to 150 min/per week). Second, school sports clubs exist in most schools. These clubs work as extra-curricular activities, which offer structured practice under the supervision of a PE teacher and have within and between school competitions. Finally, recess is generally viewed as a time for students to be active, so in most schools, few restrictions to movement are imposed during that time (Mota et al. 2018). The role of school as an important environment to promote children’s PA is highlighted by the fact that when Portuguese children do not go to school, their average PA time drops for less than half of the total time reported by accelerometry during school days, which is about 5.0 h for boys and 4.5 h for girls (Marques et al. 2016).

Although we were anticipating confirmation of the observed Portuguese trend of a moderate to vigorous decrease in moderate to vigorous PA followed by an increase in sedentary behaviors as children grow up (Baptista et al. 2011), we were not expecting the non-existing difference between boys and girls in PA engagement time. Usually, girls have lower involvement in PA and higher engagement in sedentary behaviors (Fu et al. 2016; Kann et al. 2018; Telford et al. 2016). However, during confinement, all children were in the same constrained space situation that did not allow the practice of vigorous PA, which usually needs large spaces to happen for children of this age range. This constraint might explain the lack of sex differences regarding PA engagement time in our sample.

Acknowledging that these children were taking online school classes, we saw an increase of 30–120 min (De Sousa and Mendes 2017) per day of screen time, not only to study but also for leisure purposes, when compared to the pre-confinement period. This increase was probably heavily influenced by the popularity of social networking, which was the preferred way children had to keep in touch with their friends during this period, but other screen time, related to playing video games or just watching TV, also played an important role. The fact that many children, especially the older ones, have a smartphone (Mascheroni and Ólafsson 2016; Zilka 2020), can also help to explain our results regarding the higher percentage of screen time as ages increase.

Previous research has shown that children who watch TV for more than 3 h a day have a 65% higher chance of being obese compared to children who watch less than 1 h (Singh et al. 2008) and that the presence of a TV, computer, or video game device in the child’s bedroom increases sedentary behavior (Tandon et al. 2014). Also, children with greater screen time values, show a lower academic achievement, fail more often to deliver their homework (Shin 2004), study and read less (Wiecha et al. 2001), have focusing and attention difficulties (Johnson et al. 2007), and show more learning problems (Özmert et al. 2002).

The percentage of time allocated to intellectual activities in the child’s day steadily increases with age. In the two older groups, children spent circa 4 h per day in organized or leisure intellectual activities. These values were not surprising, since children in the older age groups were already in primary school (1st to 6th grade) and many of them had several school tasks to do. It is important to emphasize that, we do not know if all children were affected in the same magnitude. We do not have any direct data regarding the social-economic status of the children or their accessibility to a computer and the internet. In Spain, middle-class families were able to maintain higher standards of education quality, while children from socially disadvantaged families had few learning opportunities both in terms of time and learning experiences (Bonal and González 2020). Access to screens is not equal across children from different SES, but we did not address this issue in the present study.

Regarding play time, we saw a decline in primary school children when compared to younger age groups, also probably caused by the number of school tasks they were required to do.

Practical Implications

Although social confinement seems to be a necessary and effective strategy to prevent the human-to-human transmission of the COVID-19, our results suggest that it is detrimental to children’s PA levels, as suggested by previous opinions (Chen et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2020). Moreover, prolonged homestay can lead to an increase in sedentary behaviors, such as spending excessive amounts of time sitting, reclining, or lying down for screening activities (playing games, watching television, using mobile devices); reducing regular PA (hence having lower energy expenditure); or engaging in activities that, consequently, lead to an increased health risk (Owen et al. 2010).

Knowing that PA can provide protection from viral infections, especially among vulnerable populations (Laddu et al. 2020), and that it seems to be associated with a lower prevalence of COVID-19-related hospitalizations (Ribeiro de Souza et al. 2020), it is necessary to think on fast solutions to protect against sedentarism and minimize the impact of such confinement in health. Considering that some countries are already experiencing a second wave of Covid-19 infection, leading to a new confinement period, along with the fact that this virus will probably not be the last one linked to zoonotic spillover events (Rodriguez-Morales et al. 2020), we recommend that:

-

(1)

Support guidelines for parents should be designed to support the interaction with their children during extraordinary periods like this one. Parents play an important role as health behavior models for children, and active parents bring up more physically active children (Sigmund et al. 2008). So, physical activity family-centered interventions, that can be done within the home environment, are important for healthy living and should be promoted during the coronavirus crisis or any other similar crisis in the future. Involving children in family activities, such as physically active games, walks in nature (following public health recommendations), and engaging in daily outside sports activity should be encouraged.

-

(2)

Playtime can also be used to improve more intense movement involvement. Combining movement and story-telling interventions enhance motor competence (Duncan et al. 2019), which is a key contributor to children’s physical, cognitive and social development, and provides the foundations for healthy living trajectories (Lubans et al. 2010).

-

(3)

Replace leisure screen time by active screen time (Tremblay et al. 2017) in which children are encouraged to engage in PA, can be another viable solution. Active video games (AVGs), also called “exergames”, are video games that require movement or physical exertion (Kann et al. 2018). Studies have shown that playing AVGs over short periods of time is similar to light-to-moderate physical activities (Biddiss and Irwin 2010; Wagener et al. 2012). However, play and PA away from screens should be the parent’s first choice for their children, when possible.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although this study provides important information considering the routines of children during this confinement situation, it is important to highlight that it has some limitations. First, it is a cross-sectional study design and thus susceptible to biases. Second, it is a parental report online and not a direct or quantifiable observation of the time children spent in each activity. We believe that these methodological options were necessary considering the confinement situation we were living in. Lastly, the fact that we could not collect any data on the SES of the respondents was a limitation. We do have indirect indicators, such as the type of house, but we do not really know the SES of the respondents, which is probably an influent factor in the way families dealt with the confinement.

Along the confinement period, different attempts to improve movement time and quality within the households appeared. Social media, YouTube channels, television programs, social influencers, organized groups (e.g., sports clubs, health clubs, universities, government health authorities, etc.), and many others tried to deliver to families and children the best ideas to help them keep active and healthy. The final consequences of this forced living style will be lived long after the end of the confinement, but a better understanding of the effects will only be possible if a thorough description of this period is possible. With this study, we hope to contribute to characterize the Portuguese children’s PA routines during the confinement period, but also to offer possible ways for changing the families’ present situation.

In conclusion, this study offers a first look at the Portuguese children’s routines within the families’ households during confinement, highlighting the impact on children’s physical activity time during this period. The results suggest that the known general decreasing trend in physical activity time that occurs along childhood also occurs when children are mandatorily confined to their homes, where the amount of physical activity is much lower. Although screen time increased along age groups, and a gender effect was detected, with girls being more involved in play without physical activity, and boys in playful screen time, there were no sex differences in overall physical activity.

Overall, this pandemic can have a harmful impact on the children’s health by increasing their sedentary behavior and decreasing their levels of physical activity, but the follow up of this situation is warranted to act appropriately. Strategies to increase activity during confinement must be targeted to each child’s specific age group, and conjoint family strategies should be promoted. The tracking of the situation over time will allow evaluating the effect of different physical activity initiatives that are appearing every day in the community intending to minimize the impact of this situation on children’s health.

Change history

31 December 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-02216-7

References

Baptista, F., Silva, A. M., Santos, D. A., Mota, J., Santos, R., & Vale, S., et al. (2011). Livro verde da actividade física. Lisboa: Instituto do Desporto de Portugal.

Baptista, F., Santos, D. A., Silva, A. M., Mota, J., Santos, R., Vale, S., Ferreira, J. P., Raimundo, A. M., Moreira, H., & Sardinha, L. B. (2012). Prevalence of the Portuguese population attaining sufficient physical activity. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 44(3), 466–473. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e318230e441.

Biddiss, E., & Irwin, J. (2010). Active video games to promote physical activity in children and youth: a systematic review. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 164(7), 664–672. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.104.

Biddle, S. J. H., Gorely, T., & Stensel, D. J. (2004). Health-enhancing physical activity and sedentary behaviour in children and adolescents. Journal of Sports Sciences, 22(8), 679–701. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410410001712412.

Bonal, X., & González, S. (2020). The impact of lockdown on the learning gap: family and school divisions in times of crisis. International Review of Education, 15, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-020-09860-z.

Carroll, N., Sadowski, A., Laila, A., Hruska, V., Nixon, M., Ma, D. W. L., & Haines, J. (2020). The impact of covid-19 on health behavior, stress, financial and food security among middle to high income Canadian families with young children. Nutrients, 12(8), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082352.

Chen, P., Mao, L., Nassis, G. P., Harmer, P., Ainsworth, B. E., & Li, F. (2020). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): The need to maintain regular physical activity while taking precautions. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 9(2), 103–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2020.02.001.

Coronatracker (2020). Corona tracker. https://www.coronatracker.com/analytics.

De Sousa, R. C., & Mendes, S. (2017). Surveillance childhood obesity initiative.

Direção-Geral da Saúde (2020). REACT-COVID—inquérito sobre alimentação e atividade física em contexto de contenção social. 1–15.

Duncan, M., Cunningham, A., & Eyre, E. (2019). A combined movement and story-telling intervention enhances motor competence and language ability in pre-schoolers to a greater extent than movement or story-telling alone. European Physical Education Review, 25(1), 221–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X17715772.

Epstein, L. H., Paluch, R. A., Gordy, C. C., & Dorn, J. (2000). Decreasing sedentary behaviors in treating pediatric obesity. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 154(3), 220–226. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.154.3.220.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146.

Fu, Y., Gao, Z., Hannon, J. C., Burns, R. D., & Brusseau, T. A. (2016). Effect of the SPARK program on physical activity, cardiorespiratory endurance, and motivation in middle-school students. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2015-0351.

Giubilini, A., Douglas, T., Maslen, H., & Savulescu, J. (2018). Quarantine, isolation and the duty of easy rescue in public health. Developing World Bioethics, 18(2), 182–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/dewb.12165.

Guan, H., Okely, A. D., Aguilar-Farias, N., del Pozo Cruz, B., Draper, C. E., El Hamdouchi, A., Florindo, A. A., Jáuregui, A., Katzmarzyk, P. T., Kontsevaya, A., Löf, M., Park, W., Reilly, J. J., Sharma, D., Tremblay, M. S. & & Veldman, S. L. C. (2020). Promoting healthy movement behaviours among children during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Child and Adolescent Health, 4(6), 416–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30131-0.

Hall, R. C. W., Hall, R. C. W., & Chapman, M. J. (2008). The 1995 Kikwit Ebola outbreak: lessons hospitals and physicians can apply to future viral epidemics. General Hospital Psychiatry, 30(5), 446–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.05.003.

Islam, N., Sharp, S. J., Chowell, G., Shabnam, S., Kawachi, I., Lacey, B., Massaro, J. M., D’Agostino, R. B., & White, M. (2020). Physical distancing interventions and incidence of coronavirus disease 2019: natural experiment in 149 countries. The BMJ, 370, m2743 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2743.

Jeong, H., Yim, H. W., Song, Y. J., Ki, M., Min, J. A., Cho, J., & Chae, J. H. (2016). Mental health status of people isolated due to middle east respiratory syndrome. Epidemiology and Health, 38, e2016048 https://doi.org/10.4178/epih.e2016048.

Johnson, J. G., Cohen, P., Kasen, S., & Brook, J. S. (2007). Extensive television viewing and the development of attention and learning difficulties during adolescence. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 161(5), 480–486. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.161.5.480.

Kann, L., McManus, T., Harris, W. A., Shanklin, S. L., Flint, K. H., Hawkins, J., Queen, B., Lowry, R., Olsen, E. O. M., Chyen, D., Whittle, L., Thornton, J., Lim, C., Yamakawa, Y., Brener, N., & Zaza, S. (2018). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 67(8), 1–114. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6708a1.

Laddu, D. R., Lavie, C. J., Phillips, S. A., & Arena, R. (2020). Physical activity for immunity protection: Inoculating populations with healthy living medicine in preparation for the next pandemic. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2020.04.006.

Lasselin, J., Alvarez-Salas, E. & & Jan-Sebastian, G. (2016). Well-being and immune response: a multi-system perspective. Current Opinion in Pharmacology, 29, 34–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2016.05.003.

Lau, H., Khosrawipour, V., Kocbach, P., Mikolajczyk, A., Schubert, J., Bania, J., & Khosrawipour, T. (2020). The positive impact of lockdown in Wuhan on containing the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Journal of Travel Medicine, 27(3). https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taaa037.

Lopes, C., Torres, D., Oliveira, A., Severo, M., Alarcão, V., Guiomar, S., Mota, J., Teixeira, P., Rodrigues, S., Lobato, L., Magalhães, V., Correia, D., Pizarro, A., Marques, A., Vilela, S., Oliveira, L., Nicola, P., Soares, S., & Ramos, E. (2017). Inquérito alimentar nacional e de atividade fisica. Dgs.

Lubans, D. R., Morgan, P. J., Cliff, D. P., Barnett, L. M., & Okely, A. D. (2010). Fundamental movement skills in children and adolescents: review of associated health benefits. Sports Medicine, 40(12), 1019–1035. https://doi.org/10.2165/11536850-000000000-00000.

Marques, A., Ekelund, U., & Sardinha, L. B. (2016). Associations between organized sports participation and objectively measured physical activity, sedentary time and weight status in youth. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2015.02.007.

Mascheroni, G., & Ólafsson, K. (2016). The mobile internet: access, use, opportunities and divides among European children. New Media and Society, 18(8), 1657–1679. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814567986.

Mattioli, A. V., Sciomer, S., Cocchi, C., Maffei, S., & Gallina, S. (2020). Quarantine during COVID-19 outbreak: Changes in diet and physical activity increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases, 30(9), 1409–1417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2020.05.020.

Moore, S. A., Faulkner, G., Rhodes, R. E., Brussoni, M., Chulak-Bozzer, T., Ferguson, L. J., Mitra, R., O’Reilly, N., Spence, J. C., Vanderloo, L. M., & Tremblay, M. S. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 virus outbreak on movement and play behaviours of Canadian children and youth: a national survey. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 17(1), 85–85. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-00987-8.

Mota, J., Santos, R., Coelho-E-Silva, M. J., Raimundo, A. M. & & Sardinha, L. B. (2018). Results from Portugal’s 2018 report card on physical activity for children and youth. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 15(2), S398–S399. https://doi.org/10.1123/JPAH.2018-0541.

Owen, N., Sparling, P. B., Healy, G. N., Dunstan, D. W., & Matthews, C. E. (2010). Sedentary behavior: emerging evidence for a new health risk. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 85(12), 1138–1141. https://doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2010.0444.

Özmert, E., Toyran, M., & Yurdakök, K. (2002). Behavioral correlates of television viewing in primary school children evaluated by the child behavior checklist. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 156(9), 910–914. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.156.9.910.

Pietrobelli, A., Pecoraro, L., Ferruzzi, A., Heo, M., Faith, M., Zoller, T., Antoniazzi, F., Piacentini, G., Fearnbach, S. N., & Heymsfield, S. B. (2020). Effects of COVID‐19 lockdown on lifestyle behaviors in children with obesity living in Verona, Italy: a longitudinal study. Obesity, 28(8), 1382–1385. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22861.

Pombo, A., Luz, C., Rodrigues, L. P., Ferreira, C., & Cordovil, R. (2020). Correlates of children’s physical activity during the Covid-19 confinement in Portugal. Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.09.009.

Ribeiro de Souza, F., Motta-Santos, D., dos Santos Soares, D., Beust de Lima, J., Gonçalves Cardozo, G., Santos Pinto Guimarães, L., Eduardo Negrão, C., & Rodrigues dos Santos, M. (2020). Physical activity decreases the prevalence of COVID-19-associated hospitalization: Brazil EXTRA study. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.14.20212704.

Rodriguez-Ayllon, M., Cadenas-Sánchez, C., Estévez-López, F., Muñoz, N. E., Mora-Gonzalez, J., Migueles, J. H., Molina-García, P., Henriksson, H., Mena-Molina, A., Martínez-Vizcaíno, V., Catena, A., Löf, M., Erickson, K. I., Lubans, D. R., Ortega, F. B. & & Esteban-Cornejo, I. (2019). Role of physical activity and sedentary behavior in the mental health of preschoolers, children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 49(9), 1383–1410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-019-01099-5.

Rodriguez-Morales, A. J., Bonilla-Aldana, D. K., Balbin-Ramon, G. J., Rabaan, A. A., Sah, R., Paniz-Mondolfi, A., Pagliano, P., & Esposito, S. (2020). History is repeating itself, a probable zoonotic spillover as a cause of an epidemic: the case of 2019 novel Coronavirus. Le Infezioni in Medicina, 1, 3–5.

Rubin, G., Potts, H., & Michie, S. (2010). The impact of communications about swine flu (influenza A H1N1v) on public responses to the outbreak: results from 36 national telephone surveys in the UK. Health Technology Assessment, 14(34), 183–266. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta14340-03.

Shaw, B., Bicket, M., Elliott, B., Fagan-Watson, B., Mocca, E., & Hillman, M. (2015). Children’s independent mobility. An International Comparison and Recommendations for Action. Retrieved from: http://www.psi.org.uk/children_mobility.

Shin, N. (2004). Exploring pathways from television viewing to academic achievement in school age children. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 165(4), 367–382. https://doi.org/10.3200/GNTP.165.4.367-382.

Sigmund, E., Turoňová, K., Sigmundová, D., & Přidalová, M. (2008). The effect of parents’ physical activity and inactivity on their children’s physical activity and sitting. Acta Gymnica, 38(4), 17–24.

Singh, G. K., Kogan, M. D., Van Dyck, P. C., & Siahpush, M. (2008). Racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, and behavioral determinants of childhood and adolescent obesity in the United States: analyzing independent and joint associations. Annals of Epidemiology, 18(9), 682–695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2008.05.001.

Stodden, D. F., Goodway, J. D., Langendorfer, S. J., Roberton, M. A., Rudisill, M. E., Garcia, C., & Garcia, L. E. (2008). A Developmental Perspective on the Role of Motor Skill Competence in Physical Activity: An Emergent Relationship. Quest, 60(2), 290–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2008.10483582.

Sun, P., Lu, X., Xu, C., Sun, W., & Pan, B. (2020). Understanding of COVID-19 based on current evidence. Journal of Medical Virology. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25722.

Tandon, P., Grow, H. M., Couch, S., Glanz, K., Sallis, J. F., Frank, L. D., & Saelens, B. E. (2014). Physical and social home environment in relation to children’s overall and home-based physical activity and sedentary time. Preventive Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.05.019.

Telford, R. M., Telford, R. D., Olive, L. S., Cochrane, T., & Davey, R. (2016). Why are girls less physically active than boys? Findings from the LOOK longitudinal study. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150041.

Tomkinson, G. R., & Olds, T. S. (2007). Secular changes in aerobic fitness test performance of Australasian children. Medicine and Sport Science, 50(Feb), 168–182. https://doi.org/10.1159/0000101361.

Tremblay, M. S., Aubert, S., Barnes, J. D., Saunders, T. J., Carson, V., Latimer-Cheung, A. E., Chastin, S. F. M., Altenburg, T. M., Chinapaw, M. J. M., Aminian, S., Arundell, L., Hinkley, T., Hnatiuk, J., Atkin, A. J., Belanger, K., Chaput, J. P., Gunnell, K., Larouche, R., Manyanga, T., … Wondergem, R. (2017). Sedentary behavior research network (SBRN)—terminology consensus project process and outcome. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0525-8.

Vandorpe, B., Vandendriessche, J., Lefevre, J., Pion, J., Vaeyens, R., Matthys, S., Philippaerts, R., & Lenoir, M. (2011). The körperkoordinationstest für kinder: reference values and suitability for 6-12-year-old children in flanders. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports, 21(3), 378–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01067.x.

Wagener, T. L., Fedele, D. A., Mignogna, M. R., Hester, C. N., & Gillaspy, S. R. (2012). Psychological effects of dance-based group exergaming in obese adolescents. Pediatric Obesity, 7(5), e68–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00065.x.

Wang, G., Zhang, Y., Zhao, J., Zhang, J., & Jiang, F. (2020). Mitigate the effects of home confinement on children during the COVID-19 outbreak. The Lancet, 395(10228), 945–947. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30547-X.

Whiting, S., Buoncristiano, M., Gelius, P., Abu-Omar, K., Pattison, M., Hyska, J., Duleva, V., Musić Milanović, S., Zamrazilová, H., Hejgaard, T., Rasmussen, M., Nurk, E., Shengelia, L., Kelleher, C. C., Heinen, M. M., Spinelli, A., Nardone, P., Abildina, A., Abdrakhmanova, S., … Breda, J. (2020). Physical activity, screen time, and sleep duration of children aged 6–9 years in 25 countries: an analysis within the WHO European childhood obesity surveillance initiative (COSI) 2015-2017. Obesity Facts. https://doi.org/10.1159/000511263.

Wiecha, J. L., Sobol, A. M., Peterson, K. E., & Gortmaker, S. L. (2001). Household television access: associations with screen time, reading, and homework among youth. Ambulatory Pediatrics, 1(5), 244–251. https://doi.org/10.1367/1539-4409(2001)001<0244:HTAAWS>2.0.CO;2.

WHO (World Health Organization) (2003). WHO | Update 58—first global consultation on SARS epidemiology, travel recommendations for Hebei Province (China), situation in Singapore. World Health Organization. http://www10.who.int/csr/sars/archive/2003_05_17/en/.

WHO, W. H. O. (2020). Situation Report-44.

Zilka, G. C. (2020). Аlways with them: smartphone use by children, adolescents, and young adults—characteristics, habits of use, sharing, and satisfaction of needs. Universal Access in the Information Society, 19, 145–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-018-0635-3.

Funding

R.C. work was partly supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology under Grant UIDB/00447/2020 to CIPER—Centro Interdisciplinar para o Estudo da Performance Humana (unit 447). L.P.R. work was partially supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., under project UID04045/2020

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing of interests.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Faculty of Human Kinetics—Lisbon University ethics committee, CEIFMH No.: 6/2020.

Research Involving Human Participants and/ or Animals

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the Helsinki Declaration on Ethical Principles for Medical Research in Human Beings (2013) and the Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine (“Oviedo Convention”, 1997).

Informed Consent

All respondents read the information about the study and gave their consent to the conditions by clicking to proceed on the first page of the survey.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pombo, A., Luz, C., Rodrigues, L.P. et al. Effects of COVID-19 Confinement on the Household Routines Of Children in Portugal. J Child Fam Stud 30, 1664–1674 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-01961-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-01961-z