Abstract

Objectives

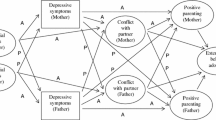

The impact of parental depressive problems on children’s depressive symptoms has been widely studied. The stress-buffering hypothesis states that social support acts as a protective factor between the impacts of stress from negative life events on physical and psychological health. The current study examined the stress-buffering hypothesis in terms of the relationship between parental depressive problems and emerging adult depressive problems.

Methods

Participants included 708 emerging adults who reported on their parents’ and their own depressive problems as measured by the Adult Behavior Checklist and Adult Self Report, respectively. Participants also reported their perceived social support using a modified version of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, received social support using the Inventory of Socially Supportive Behavior, and negative life events using the Risky Behavior and Stressful Events Scale.

Results

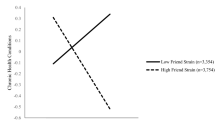

Neither perceived nor received social support significantly moderated the aforementioned relationship. When parental depressive problems were added to the model, the three-way interaction among received social support, perceived stress, and paternal depressive problems on male depressive problems was significant (b = 0.22).

Conclusions

Perceptions of available support may be more important than received support when buffering between stress and depression. Likewise, parental depression may have a stronger influence on emerging adult outcomes over and beyond negative life events. Other significant pathways and models were discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2003). Manual for the ASEBA adult forms and profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families.

Appleyard, K., Egeland, B., & Sroufe, L. A. (2007). Direct social support for young high risk children: relations with behavioral and emotional outcomes across time. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35, 443–457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-007-9102-y.

Auerbach, R. P., Bigda-Peyton, J. S., Eberhart, N. K., Webb, C. A., & Ho, M. H. (2011). Conceptualizing the prospective relationship between social support, stress, and depressive symptoms among adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 475–487. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9479-x.

Barker, E. D., Copeland, W., Maughan, B., Jaffee, S. R., & Uher, R. (2012). Relative impact of maternal depression and associated risk factors on offspring psychopathology. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 200, 124–129. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.092346.

Barrera, M., Sandler, I. N., & Ramsay, T. B. (1981). Preliminary development of a scale of social support: studies on college students. American Journal of Community Psychology, 9, 435–447. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00918174.

Bodie, G. D., Burleson, B. R., & Jones, S. M. (2012). Explaining the relationships among supportive message quality, evaluations, and outcomes: a dual-process approach. Communication Monographs, 79, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2011.646491.

Burton, E., Stice, E., & Seeley, J. R. (2004). A prospective test of the stress-buffering model of depression in adolescent girls: no support once again. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 689–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.689.

Campbell, S. B., Morgan-Lopez, A. A., Cox, M. J., & McLoyd, V. C. (2009). A latent class analysis of maternal depressive symptoms over 12 years and offspring adjustment in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118, 479–493. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015923.

Cassel, J. (1976). The contribution of the social environment to the host resistance. American Journal of Epidemiology, 104, 107–123.

Colarossi, L. G., & Eccles, J. S. (2003). Differential effects of support providers on adolescents’ mental health. Social Work Research, 27, 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/27.1.19.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191.

Hammen, C., Hazel, N., Brennan, P. A., & Najman, J. (2012). Intergenerational transmission and continuity of stress and depression: depressed women and their offspring in 20 years of follow-up. Psychological Medicine, 42, 931–942.

Hyde, J. S., Mezulis, A. H., & Abramson, L. Y. (2008). The ABCs of depression: integrating affective, biological, and cognitive models to explain the emergence of the gender difference in depression. Psychological Review, 115, 291–313.

Kendler, K. S., Gardner, C. O., Neale, M. C., & Prescott, C. A. (2001). Genetic risk factors for major depression in men and women: similar or different heritabilities and same or partly distinct genes? Psychological Medicine, 31, 605–616.

Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 4th edn. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Lakey, B., & Cohen, S. (2000). Social support theory and measurement. In S. Cohen, L. G. Underwood & B. H. Gottlieb (Eds.), Social support measurement and intervention: a guide for health and social scientists (pp. 29–52). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Maulik, P. K., Eaton, W. W., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2010). The effect of social networks and social support on common mental disorders following specific life events. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 122, 118–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01511.x.

McCarty, C. A., & McMahon, R. J. (2003). Mediators of the relation between maternal depressive symptoms and child internalizing and disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of Family Psychology, 17, 545–556. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.545.

Miller, E. D. (2013). Why the father wound matters: consequences for male mental health and the father-son relationship. Child Abuse Review, 22, 194–208. https://doi.org/10.1002/car/2219.

O’Hare, T., Sherrer, M. V., & Shen, C. (2006). Subjective distress from stressful events and high-risk behaviors as predictors of PTSD symptom severity in clients with severe mental illness. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 19, 375–386. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20131.

Pakenham, K. I., & Bursnall, S. (2006). Relations between social support, appraisal and coping and both positive and negative outcomes for children of a parent with multiple sclerosis and comparisons with children of healthy parents. Clinical Rehabilitation, 20, 709–723. https://doi.org/10.1191/0269215506cre976oa.

Pakenham, K. I., Smith, A., & Rattan, S. L. (2007). Application of a stress and coping model to antenatal depressive symptomatology. Psychology, Health, & Medicine, 12, 266–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500600871702.

Raffaelli, M., Andrade, F. C. D., Wiley, A. R., Sanchez‐Armass, O., Edwards, L. L., & Aradillas‐Garcia, C. (2013). Stress, social support, and depression: a test of the stress‐buffering hypothesis in a Mexican sample. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 23, 283–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12006.

Rueger, S. Y., Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2008). Gender differences in the relationship between perceived social support and student adjustment during early adolescence. School Psychology Quarterly, 23, 496–514. https://doi.org/10.1037/1045-3830.23.4.496.

Rueger, S. Y., Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2010). Relationship between multiple sources of perceived social support and psychological and academic adjustment in early adolescence: comparisons across gender. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 47–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9368-6.

Rueger, S. Y., Malecki, C. K., Pyun, Y., Aycock, C., & Coyle, S. (2016). A meta-analytic review of the association between perceived social support and depression in childhood and adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 142, 1017–1067. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000058.

Rughani, J., Deane, F. P., & Wilson, C. J. (2011). Rural adolescents’ help‐seeking intentions for emotional problems: the influence of perceived benefits and stoicism. The Australian Journal of Rural Health, 19, 64–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1584.2011.01185.x.

Santini, Z. I., Koyanagi, A., Tyrovolas, S., Mason, C., & Haro, J. M. (2015). The association between social relationships and depression: a systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 175, 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.049.

Sen, B. (2004). Adolescent propensity for depressed mood and help seeking: race and gender differences. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 7, 133–145.

Thoits, P. A. (2011). Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52, 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510395592.

Väänänen, A., Vahtera, J., Pentti, J., & Kivimäki, M. (2005). Sources of social support as determinants of psychiatric morbidity after severe life events: prospective cohort study of female employees. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 58, 459–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.10.006.

WHOQOL Group (1998). Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychological Medicine, 28, 551–558.

Wilson, S., & Durbin, E. (2010). Effects of paternal depression on fathers’ parenting behaviors: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 167–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.10.007.

Winer, E. S., & Salem, T. (2016). Reward devaluation: dot-probe meta-analytic evidence of avoidance of positive information in depressed persons. Psychological Bulletin, 142, 18–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000022.

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52, 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2.

Zubenko, G. S., Hughes, H. B.III, Maher, B. S., Stiffler, J. S., Zubenko, W. N., & Marazita, M. L. (2002). Genetic linkage of region containing the CREB1 gene to depressive disorders in women from families with recurrent, early‐onset, major depression. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 114, 980–987.

Author Contributions

ES designed and executed the study, performed the data analyses, and wrote the paper. CM assisted with the data analyses and collaborated in the writing and editing of the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All participants were treated according to APA ethical standards. IRB approval was received from Mississippi State University.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from every participant in the study in accordance with APA ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Szkody, E., McKinney, C. Stress-Buffering Effects of Social Support on Depressive Problems: Perceived vs. Received Support and Moderation by Parental Depression. J Child Fam Stud 28, 2209–2219 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01437-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01437-1