Abstract

Despite important advances, empirical evidence regarding the impact of divorce on children is mixed, ranging widely in its conclusions regarding the intensity, chronicity, and harmfulness of parental divorce on their post-divorce adjustment. To explain the broad range of findings, we suggest that successful and dysfunctional adjustment following parental divorce may not be mutually exclusive. Rather, they may be partly independent, and children may report divorce-specific traumatic feelings as well as a relatively high post-divorce adjustment. We examined these suggestions in a sample of 142 six-to-18-year-old Dutch children whose parents were involved in high-conflict divorces. Children completed self-reported measures of post-divorce traumatic impact and adjustment. Consistent with our suggestion, children showed, on average, both high levels of trauma and high levels of post-divorce adjustment. Nevertheless, illustrating domain spill-over, at the individual level, children who experienced more traumatic impact of the divorce also reported lower levels of post-divorce adjustment. These results suggest that high-conflict divorce represents a risk for traumatic impact, and, at the same time, children demonstrate resilience. Future research examining which children are more susceptible to trauma and/or resilience over time would be promising.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In the Netherlands, nearly 40% of first marriages end in divorce (Centraal Bureau voor Statistiek 2016), and in more than 50% of divorce cases children are involved (Spruit and Kormos 2010). Given the large number of children affected by divorce each year, a key question is whether and how children adjust to their parents’ divorce. This is especially important in high-conflict divorce cases, in which a divorce is at its worst. In the Netherlands, around 20% of the divorce cases develop into a high-conflict divorce (Association of Dutch Municipalities 2015). Although there is no clear definition of high-conflict divorce, researchers and professionals agree that parents involved in a high-conflict divorce are characterized by long-lasting conflict, hostility, blame, criticism, and the inability to take responsibility for their part in the dispute (Anderson et al. 2010), and may even engage in domestic violence (Fotheringham et al. 2013). Additionally, parents who are involved in high-conflict divorces typically show minimal, and often even a complete lack, of understanding of the effects of their conflicts on the children (Amato 2001; Johnston 1994; Kelly and Emery 2003). Given the potentially devastating effects of a high-conflict divorce on children’s adjustment (Amato 2001; Johnston 1994; Kelly and Emery 2003), it is surprising that only little research attention has been devoted to children’s post-divorce adjustment following high-conflict divorce.

The literature on the effects of parental divorce for children often has focused on whether experiencing divorce affects children’s post-divorce adjustment and, if so, why and how. Despite important advances, empirical evidence regarding the impact of divorce on children is mixed, ranging widely in its conclusions regarding the intensity, chronicity, and harmfulness of parental divorce on children’s adjustment (Amato 2010; Cherlin 1999; Kelly and Emery 2003; Lansford 2009). On the one hand, research suggests that the effects of divorce on children are irreversible and devastating, and that children carry a long-lasting, traumatic burden years after the divorce, particularly in terms of psychological wellbeing and social relationships (e.g., Amato 2000, 2010; Hetherington 2006; Sun 2001; Sun and Li 2002; Wolfinger 2000, 2005). On the other hand, research suggests that divorce has few measurable long-term effects on children, and instead, after the initial impact of divorce, most children adapt well to the divorce of their parents (e.g., Amato and Afifi 2006; Harris 1998; Kelly 2000; Kelly and Emery 2003). To explain these disparities, it could be that both conclusions may hold simultaneously. High-conflict parental divorce represents a risk for traumatic impact, and, at the same time, it may represent a risky context in which children may demonstrate resilience (Masten 2011).

According to a divorce-stress-adjustment perspective (Amato 2000), children’s adjustment is a complex combination of parent, child, and contextual factors before, during, and after the divorce (e.g., Amato 2001, 2010; Lansford 2009). Importantly, research suggests that the legal divorce itself has few direct effects on children (e.g., Amato 2000). Rather, risk factors preceding and following the divorce in the short- and in the long-term (e.g., parental conflict, residential moves, change of school) heighten the chance of behavioral, social, and academic problems among children. Most existing research on children’s adjustment following parental divorce can be interpreted within this comprehensive framework (e.g., Amato 2010; Lamb 2012).

To understand the disparities in children’s adjustment following divorce, it is important to consider additionally that children function in different life domains, including school, friendships, leisure, and family. Although the different domains may partly overlap, they are also partly independent. In the context of divorce, it is likely that children’s divorce-specific experiences (e.g., emotions, cognitions, behavior) spill over to their general adjustment to the divorce (e.g., Flook and Fuligni 2008). Indeed, parental divorce can create lingering feelings of pain, worry, and regret that negatively affects children’s daily functioning in different domains (e.g., Alisic et al. 2008; Hetherington and Stanley-Hagan 1999). Nevertheless, it is also possible that children’s divorce-specific experiences are partly independent of their experiences in other domains, especially in the long-run as the time since the divorce increases (e.g., Kelly and Emery 2003). Laumann-Billings and Emery (2000), for example, showed that children whose parents divorced for two or more years did not score lower than children with continuously married parents on measures of psychological symptoms, such as depression or anxiety. These findings suggest that children may experience both divorce-specific trauma and post-divorce adjustment at the same time.

This line of reasoning fits well with the idea that children are active agents who adapt to challenges in the environment, thereby shaping their own adjustment (e.g., Frankenhuis et al. 2016; Lamb 2012). It is also consistent with the notion that while bad things happen and may be potentially traumatic for both adults and children (e.g., Bonanno 2004), not everybody reacts the same way. For example, research suggests that in the face of adversity, children show increased variability in behavior and outcomes, because they adapt and react differently to stressful environments (Belsky 2008; Ellis et al. 2012). Hence, the distinction between resilience and maladjustment to stressful events unfolds over time, resulting in heterogeneous trajectories, ranging from chronic dysfunction to recovery (Bonanno and Diminich 2013).

Also, a growing literature on resilience and positive developmental outcomes following adversities suggests that although the effects of traumatic experiences may spill over from one domain of functioning (e.g., family) to another (e.g., school) (Masten and Cicchetti 2010), this is not necessarily the case. Rather, despite experiencing adversity in one domain (e.g., sexual abuse, poverty), some children and adults may show competent functioning across multiple domains, including social relationships and job and school performance (Masten and Narayan 2012; Miller et al. 2011). Extending these findings to the context of parental divorce, a child may struggle (sometimes for years) with the social and emotional aftermath of parental divorce but may show resilience if he or she masters normal developmental tasks (e.g., initiating and maintaining friendships) and milestones (e.g., getting a diploma), and post-divorce adjustment.

In short, successful and dysfunctional adjustment following parental divorce may not be mutually exclusive. Rather, they may be partly independent, and children may on average report divorce-specific traumatic feelings as well as a relatively high post-divorce adjustment. This prediction bears particular importance in the realm of high-conflict divorces which are mired in conflict and separating parents are unable to resolve differences over alimentation, child custody, visitation, or methods of child rearing (Johnston 1994).

Studies of risk and resilience among varying populations of children exposed to traumatic events and adversity show that certain factors are associated with better psychosocial outcomes. Specifically, the literature has identified protective factors in the context of divorce that may buffer the potentially traumatic impact of parental divorce on children’s post-divorce adjustment. One of the most prominent moderating factors is the level of parental conflict children experience in the aftermath of their parents’ separation (e.g., Hetherington 2006; Tein et al. 2000). That is, children who are exposed to long-lasting, intense, and bitter conflict between their parents after the divorce are more depressed and show more psychological symptoms than children whose parents have only minor conflict (Amato and Keith 1991; Zill et al. 1993). Another factor that may moderate the association between divorce-specific trauma and adjustment is the time since the divorce took place. Many children show considerable improvements in adjustment and better adaptation over time (e.g., Hetherington 1989).

In order to develop interventions targeting children, it is important to identify child-specific resources that may play a role in children’s risk and resiliency following parental divorce. These resources can be promotive factors (i.e., predictors of better outcomes under high- as well as low-risk conditions) or protective factors (i.e., factors buffering high-risk conditions) (Brumley and Jaffee 2016; Cicchetti 2010; Masten 2001). Children’s level of self-esteem and perceived control may be resources that buffer the impact of parental divorce on children’s adjustment, either as promotive or protective factor. First, children with a relatively higher level of self-esteem are more likely to evoke positive responses and support from others (e.g., Dumont and Provost 1999), and are better able to adapt to new challenges and stressful life experiences than children with a relatively lower self-esteem (Hetherington 1991). Based on these findings, a higher self-esteem may be a promotive factor, because children with higher self-esteem are better in coping with the stressful divorce of their parents. It may also be a protective factor, which moderates the relation between divorce-specific traumatic impact and children’s adjustment. Second, a large number of children report that they are not adequately (or not at all) informed about the divorce and its implications for their lives (e.g., Dunn et al. 2001). This lack of information negatively affects children’s perceived control over their lives (Kelly and Emery 2003). Because perceived control is associated with higher wellbeing (e.g., Benight and Bandura 2004), level of perceived control may be a promotive factor. It may also be a protective factor, in which perceived control moderates the link between traumatic impact of divorce and children’s adjustment, such that divorce shows a weaker relation with children’s post-divorce adjustment if they perceive more control over their lives.

The main aim of the present research was to reconcile mixed findings on the adjustment of children whose parents are involved in a high-conflict divorce. While previous work mostly relied on samples of North American children, we examined our hypotheses in a group of children whose parents were involved in a high-conflict divorce in The Netherlands. In a first step, we adopted an average-level approach and included measures of divorce-related traumatic impact and children’s post-divorce adjustment. In a second step, we adopted a within-person approach to examine the link between divorce-specific trauma and post-divorce adjustment and identify promotive and protective factors (i.e., perception of parental conflict, time since divorce, self-esteem, and perceived control). In addition, we controlled for the gender and age of the child.

Method

Participants

We used data from the No Kids in the Middle [Kinderen uit de Knel] project (Schoemaker et al. 2017), a two-wave study among families involved in a high-conflict divorce in The Netherlands. All families were referred to a health care institution for a group intervention by judges or child protection services because the wellbeing of the children was threatened by the ongoing conflict between the parents. Participation in the intervention was obligatory, but participation in the study was voluntary. Of the 173 parents who were invited to participate in the study, 165 agreed, resulting in a response rate of 95% for parents. The data relevant to the current analyses were collected at the first wave before the intervention, among children of six years and older. Of the 193 children who were invited to participate in the study, 142 received parental permission and consented themselves, resulting in a response rate of 74% for children. The 142 children who participated in the study came from 81 families (first child; n = 81, second child; n = 51, third child; n = 9, fourth child; n = 1 and ranged in age from 6 to 18 years old (67 girls; Mage = 10.21, SDage = 2.77). Most of the children lived with their mother and father (co-parenting; 43%) or only the mother (40%). The rest of the children lived with only their fathers (7%), or in other living arrangements (10%).

Procedure

Parents were recruited from 17 outpatient health care institutions in different urban and rural regions of the Netherlands and Belgium. All parents were referred by judges, Youth Care Agencies (in Dutch: Bureau Jeugdzorg or Veilig Thuis), or a physician, because the wellbeing of their child(ren) was severely compromised by the severity of the conflicts between the separated or divorced parents. After the referral, parents enrolled in the intervention No Kids in the Middle (Van Lawick and Visser 2015), which is a two-weekly intervention program for families involved in high-conflict divorces. Parents and children start together in one group, and after 10 min they separate and participate in two parallel groups, one for the parents and one for the children (8 sessions).

Parents were invited for clinical intake as soon as they had both signed up for the intervention separately. Together with the written invitation, parents received information about the study entitled “Parenting in the Aftermath of Divorce and No Kids in the Middle: an ongoing study among divorced families.” During the first clinical intake, questions about the study were answered. Children between the ages of 6 and 18 were also invited to participate in the study, provided both authoritative parents had given permission. Children from 12 years of age additionally had to sign a consent form themselves. Before signing, the children received an information letter and were given the opportunity to ask questions. Children under the age of 6 could not participate in the study, because they are likely unable to read independently, and the questions would be too difficult to answer for them.

All children completed the questionnaire at the first meeting in the institution in the presence of research assistants to diminish parental influence that they may experience when answering the questions at home. Young children or children with reading problems received additional assistance. There was always the possibility for children to ask questions during the study. All questionnaires were programmed in Qualtrics, an online survey software program

Measures

Post-divorce adjustment

We measured children’s post-divorce adjustment with the KIDSCREEN-10 (Ravens-Sieberer et al. 2010). This unidimensional measure represents a global score for the dimensions of the longer KIDSCREEN versions (Ravens-Sieberer et al. 2013). Children rated each of the 10 items for the past week, on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = moderately, 4 = much, and 5 = always). Example items are: “Have you felt fit and well?”, and “Have you had fun with your friends?”. Two items were reversed when scoring the questionnaire, so that higher values indicate better adjustment. The calculation of the KIDSCREEN index involves three steps: firstly, a raw overall score is summed; secondly, the sum scores are converted to a score by assigning Rasch person parameters to each possible sum score; and lastly, the person parameters are transformed into values with a mean of approximately 50 and standard deviation of approximately 10 (see e.g., Ravens-Sieberer et al. 2010). Cronbach’s α in this sample was .82.

Traumatic impact

Children’s traumatic impact of the high-conflict divorce of their parents was measured with the Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale (CRIES-13; originally developed by Horowitz et al. 1979; translated to Dutch by Van der Ploeg et al. 2004), which provides a stable assessment of traumatic impact across different types of trauma and life-threatening events (e.g., Perrin et al. 2005). Children rated 13 items according to the frequency of their occurrence in the past week in relation to the conflicts and divorce of their parents (1 = none, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, and 4 = often). Example items are: “Do you think about the divorce of your parents even when you don’t mean to?”, and “Do you avoid talking about the divorce of your parents?” We used the sum score as an indicator of traumatic impact (ranging from 0 to 65). A score of 30 and over has been suggested as the most efficient cut-off for discriminating heightened risk for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD, Verlinden et al. 2014). Cronbach’s α in this sample was .87.

Perceived parental conflict

To assess perceived parental conflict, children were asked to indicate on a 5-point scale (1 = never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = regularly, 4 = often, and 5 = always) to what extent their parents fight in their presence.

Time since divorce

Parents indicated the date they separated. We used the difference between participation date (this study) minus the separation date as indicator of time since the divorce, which ranged from 0 to 12 years.

Self-esteem

Children’s level of self-esteem was measured with a single item, as suggested by Robins et al. (2001). On a 5-point scale, children indicated to what extent they generally feel good about themselves (1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = moderately, 4 = much, and 5 = always). This is a reliable indicator of self-esteem and existing research demonstrated it to be as valid as a multi-item scale (Robins et al. 2001).

Perceived control

Children’s level of perceived control was also measured with one-item. On a 5-point scale, children indicated to what extent they have the feeling that they have control over what happens to them (1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = moderately, 4 = much, and 5 = always).

Data Analyses

First, we ran descriptive and average-level analyses in order to provide more information about the outcome scores of children’s adjustment and traumatic impact as compared to norm scores. Next, we zoomed in on within-person analyses and conducted correlational analyses between children’s adjustment and level of traumatic impact. Finally, we explored promotive or protective factors on the impact of divorce on children’s post-divorce adjustment. Given that 81 of the 142 children belonged to the same family, the data had a nested structure. To deal with this interdependence, we conducted multilevel modelling analyses using the SPSS mixed-effects models procedure and restricted maximum likelihood estimation. We mean-centered children’s traumatic impact, perceived parental conflict, time since divorce, self-esteem, and perceived control. In addition, as control variables, we added children’s gender (−1 represented boys and 1 represented girls) and children’s age.

We ran four separate moderation analyses exploring the effects of each of the promotive or protective factors; perceived parental conflict, time since divorce, self-esteem, and perceived control. In all four analyses, we entered participants’ self-reported post-divorce adjustment, traumatic impact, one of the promotive/protective factors, and the interaction effect between traumatic impact and one of the promotive/protective factors as continuous variables, and family as a fixed effect. All models tested the main effects of traumatic impact, children’s gender and age, and additionally the main effects of one of the promotive/protective factors, and the interaction effects between one of the promotive/protective factors and traumatic impact (i.e., traumatic impact and perceived parental conflict, traumatic impact and time since divorce, traumatic impact and self-esteem, and traumatic impact and perceived control).

Results

Confirmatory Analyses: Children’s Adjustment and Traumatic Impact

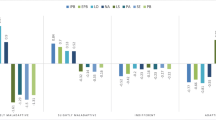

The descriptive statistics are reported in Table 1. As can be seen, children scored relatively high on post-divorce adjustment (M = 52.23, SD = 15.03, with a range from 17.50 to 87.88, which is comparable to national norm data of Dutch children and adolescents aged 8–18 years old (M = 53.90 SD = 10.40; see Ravens-Sieberer et al. 2010)). This finding supports the idea that children seem to be resilient and may—ultimately—adjust well to the divorce of their parents (Amato 2010). At the same time, on average, children continued to experience the traumatic impact of their parents’ divorce (M = 27.27, SD = 15.28, with a range from 0 to 65). More specifically, in our sample, 45.8% of the children scored within the clinical range (which is a score of 30 or higher; n = 49; Verlinden et al. 2014). This means that almost half of the children reported to have divorce-related post-traumatic stress symptoms. In addition, and in line with previous work (e.g., Wigfield, Eccles, Mac Iver, Reuman, & Midgley, 1991), we found a significant gender difference on self-esteem, such that boys reported higher levels of self-esteem than girls.

The correlations are reported in Table 2. Most importantly, there was a strong negative correlation between post-divorce adjustment and traumatic impact (r = −.57). In addition, post-divorce adjustment correlated positively with self-esteem (r = .42), whereas traumatic impact correlated negatively with self-esteem (r = −.32). Traumatic impact was also positively correlated with perceived parental conflict (r = .19). Children’s age correlated positively with time since divorce (r = .37), and with perceived control (r = .20). The same correlations were computed for boys and girls separately and compared using Fisher’s r-to-z transformations. None of the correlations differed by gender, p’s > .05.

In summary, on average children scored relatively high on post-divorce adjustment and relatively high on traumatic impact. These findings are in line with our reasoning suggesting that, on an average level, successful and dysfunctional adjustment following parental divorce may be partly independent from each other. At the same time, we found a correlation between children’s post-divorce adjustment and traumatic impact of divorce, with better adjustment being associated with relatively less traumatic impact. This indicates that successful and dysfunctional adjustment following divorce partly overlap when focusing on individual children.

Exploratory Analyses: Promotive or Protective Effects

To explore protective and promotive factors, we conducted four sequential moderation analyses with traumatic impact as independent variable, post-divorce adjustment as dependent variable, and respectively perceived parental conflict, time since divorce, self-esteem, and perceived control as moderators, while controlling for children’s gender and age.

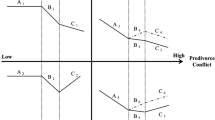

Consistent with the above-reported results of the correlational analyses, in the first analysis with perceived parental conflict as moderator, we found a main effect of traumatic impact, b = −9.43, 95% CI [−12.12 to −6.74], p < .001, suggesting that a higher traumatic impact following divorce is associated with lower levels of post-divorce adjustment. Additionally, we found a significant main effect of age, b = −4.91, 95% CI [−7.76 to −2.07], p = .001, indicating that older children tend to have relatively lower levels of post-divorce adjustment. Importantly, we did not find a significant interaction effect between traumatic impact and perceived parental conflict, p = .263 (Fig. 1), nor a main effect of perceived parental conflict, p = .547, or children’s gender, p = .871.

In the second analysis with time since divorce as moderator, we again found a main effect of traumatic impact, b = −9.43, 95% CI [−12.13 to −6.73], p < .001, and a significant main effect of age, b = −4.57, 95% CI [−7.75 to −1.39], p = .005. We did not find a significant interaction effect between traumatic impact and time since divorce, p = .974 (Fig. 2), nor a main effect of time since divorce, p = .587, or children’s gender, p = .906.

The third analysis with children’s self-esteem as potential moderator revealed a main effect of traumatic impact, b = −7.88, 95% CI [−10.40 to −5.36], p < .001, and a main effect of self-esteem on children’s post-divorce adjustment, b = 4.57, 95% CI [1.84 to 7.29], p = .001. This indicates that higher levels of self-esteem are positively associated with post-divorce adjustment. We also found a significant main effect of age, b = −3.91, 95% CI [−6.61 to −1.21], p = .005. We did not find an interaction effect between traumatic impact and self-esteem, p = .509 (Fig. 3), nor a main effect of children’s gender, p = .348.

Finally, the fourth analysis with perceived control as moderator revealed a main effect of traumatic impact, b = −9.34, 95% CI [−11.90 to −6.77], p < .001, and a main effect of age, b = −5.25, 95% CI [−8.15 to −2.35], p = .001. We did not find a main effect of perceived control, p = .127, nor an interaction effect between traumatic impact and perceived control, p = .585 (Fig. 4), nor a main effect of gender, p = .946.

Discussion

To shed light on disparities in children’s adjustment after divorce in high-conflict divorce situations, we adopted a risk-and-resilience perspective. We proposed that high-conflict divorce may be a context may put children at risk for suffering and trauma but at the same time may be a context in which children may show their resilience. A first goal of the present research was therefore to examine both the traumatic impact of divorce and the post-divorce adjustment in children whose parents are involved in a high-conflict divorce. Consistent with our suggestion, the findings of our study revealed that despite the high-conflict divorce of their parents, on average, children reported post-divorce adjustment and, simultaneously, considerable levels of divorce-specific traumatic impact. At the same time, at the individual level, we observed domain spill-over, such that children who experienced higher traumatic impact following the divorce demonstrated a lower post-divorce adjustment. Together, these findings underline that the analytical approach shapes the answer to the question how children adjust to the adversity of high-conflict divorce. Using an average-level approach allows researchers to examine differences between individuals or groups. In our study, the mean of children’s post-divorce adjustment was, despite the experienced adversity of their parents’ high-conflict divorce, comparable to the national norm, highlighting children’s resilience. At the same time, the mean divorce-related post-traumatic stress symptoms were considerable with almost half of the children experiences clinical levels. Using a correlational within-person approach, on the contrary, our results highlighted the risk of divorce-related trauma for children’s post-divorce adjustment, showing that children who experienced more divorce-related trauma experienced less post-divorce adjustment.

The differences in the statistical approaches used in different studies investigating children’s adjustment after divorce (mean level differences between groups vs. correlations between variables within individuals and between groups) may have hampered the translation of findings from one field of study to the other and may have contributed to the disparities in research findings. For example, professionals in the field may feel confused about how a child can report high adjustment, and yet psychosocial intervention studies can target and improve this same adjustment, by targeting divorce-related traumatic symptoms, as suggested by our findings. Consistent with other studies on trauma in children (e.g., Alisic et al. 2008), our findings encourage professionals and research to look at the broad range of reactions, positive and negative, that children show in the aftermath of divorce. The high rate of divorce-related post-traumatic stress found in our sample of children whose parents were involved in high-conflict divorces may indicate that these divorces can be considered a traumatic event as defined by the A1 criterion of the DSM-IV-TR or DSM-5 Trauma, especially if domestic violence or abuse is involved (Alisic et al. 2014; Fotheringham et al. 2013).

A second goal of the present research was to explore the influence of several promotive or protective factors on children’s adjustment following divorce. Based on previous work, we reasoned that children would differ in the extent to which the traumatic impact spills over to their overall adjustment, exploring the moderating roles of perceived parental conflict, time since the divorce, self-esteem, and perceived control (e.g., Dumont and Provost 1999; Hetherington 2006; Kelly and Emery 2003). These analyses yielded a main effect of self-esteem on post-divorce adjustment, suggesting that self-esteem is a promotive, rather than a protective factor. Self-esteem is crucial to mental and social wellbeing across the life-span by fostering aspirations and personal goals, active coping with adversity, and interaction with others (Kuster et al. 2013; Mann et al. 2004; Thoits 2010). High self-esteem also helps vulnerable youth to cope with the psychological consequences of divorce (e.g., Palosaari and Aro 1995). This result suggests that pre-divorce, peri-divorce, and post-divorce interventions that further bolster children’s sense of empowerment and self-esteem may be particularly promising in ameliorating distress and fostering resilience among children whose parents are involved in high-conflict divorces (Van der Wal et al. 2017).

The results did not reveal conclusive evidence for a promotive or protective role of perceived parental conflict, time since the divorce, or perceived control on the association between traumatic impact and post-divorce adjustment. The exploratory analyses revealed a main effect of age on post-divorce adjustment, such that younger children tended to adjust better than older children. Previous studies have shown mixed results with respect to how children’s age affects their adjustment to divorce (e.g., Allison and Furstenberg 1989; Lansford et al. 2006). Because the transition from childhood to adolescence is marked by developmental changes at all levels of functioning, examining whether this effect is related to divorce-related experiences and/or age-related developmental changes would be particularly informative.

Although previous work recognized the disparity of findings regarding children’s adjustment following divorce, most of these inconsistencies were attributed to pre- and post-divorce differences between groups of children (e.g., Amato 2010; Lansford 2009). Such a divorce-stress-adjustment perspective helps to get a better understanding of the impact of divorce on children’s post-divorce adjustment. As described above, we suggest that, in addition to such a mean-level approach, it is essential to differentiate between average and within-person effects. Specifically, the relatively high mean levels of post-divorce adjustment, on the one hand, and high levels of divorce-related traumatic symptoms, on the other hand, suggest that children whose parents are involved in high-conflict divorces, on average, show resilience in the face of adversity. These average effects are consistent with research showing that positive and negative outcomes following traumatic life-events can coexist (Alisic et al. 2008). However, significant correlations between divorce-related traumatic impact and children’s post-divorce adjustment illustrate that, at the individual level, divorce-specific trauma spill over and extend beyond the specific domain of family to broader areas of life. In addition, more research, ideally, prospective, longitudinal studies are needed to examine boundary conditions to our findings. For instance, it is important to explore to what extent the quality of post-separation co-parenting relationships may alleviate the spill-over effect of divorce-related trauma (see e.g., Hardesty et al. 2017). Also, the role of domestic violence warrants attention (Fotheringham et al. 2013), such that future research should examine whether children who are targets vs. witnesses of domestic violence are differentially susceptible to suffer from divorce-specific stress.

Strengths, Limitations and Future Research Directions

Before closing, it is important to note several strengths and limitations of the present work. First, the cross-sectional design of the present study prevents us from drawing firm conclusions about causal effects of the divorce itself on traumatic impact and post-divorce adjustment. For example, differences in children’s adjustment measured after the divorce may be influenced by pre-divorce differences between children (e.g., Sun 2001; Sun and Li 2002). Yet, despite pre-divorce differences, it is also likely that children exhibit a further decrease in adjustment following divorce (e.g., Strohschein 2005). Future prospective, longitudinal research whereby wellbeing is measured before and after the divorce is needed to reveal such causal relations. Second, the data employed in this study relied on a single study among children in The Netherlands whose parents were involved in high-conflict divorce. In our study, all families were referred to treatment by child protection services or judges, because the wellbeing of the child was threatened by parents’ ongoing conflict. While this sample provides unique insights in an understudied group of children, our findings warrant replication in other studies, for example, with groups of children whose parents divorced but not necessarily with a lot a conflict, or with groups of children whose parents did not marry but only cohabitated. Moreover, because legal and clinical decision-making regarding divorce differ across regions, professionals, and countries, research is needed to examine whether these differences affect the generalizability and robustness of our results. Third, the findings rely on self-reports. We chose self-report in the first meeting to ensure confidentiality and avoid socially desirable answers. Nevertheless, replication of the study with clinical interviews would be valuable. Finally, only the children themselves were asked to report on their experiences of parental conflict. Parents and children may differ in their interpretation and evaluation of conflict. For example, what parents may describe as a heated discussion, children may perceive as negative and threatening, especially when they have been exposed to interparental conflict during longer periods of time (Davies et al. 2006). Research in which parents, children, and other informants, such as teachers, can complement each other in reports of conflict would be particularly promising to increase our understanding of children’s perception of parental conflict in the divorce context.

The finding that these high-risk children reported comparable adjustment levels to other Dutch children is somewhat surprising and warrants further research. First, it is possible that our findings validly reflect children’s perceptions and experiences and indicate that children have adapted to their parents’ divorce, regretting some aspects but creating a new normal. Second, based on Hetherington’s (2006) observations, it is possible that some children attempt to protect their parents by minimizing their distress. Third, it is also possible that the timing of the assessment, just before an intervention program that reunites parents for the better of the children, may have led children to feel hopeful about change in their families, and possibly a parental reunification. Indeed, research suggests that children’s irrational beliefs about divorce, especially hope for reunification is persistent and long-lasting (DeLucia-Waack and Gellman 2007). More research, ideally longitudinal studies, including children whose parents are involved in high-conflict divorces but do not participate in interventions would be promising.

Future research further examining individual differences in children’s adjustment following divorce would also be promising. Which environmental factors and/or personality traits may buffer the traumatic impact of divorce on children’s post-divorce adjustment? To illustrate, because the relationship between child(ren) and (one of) the parents is often damaged when parents decide to divorce (e.g., Booth and Amato 1994), being able to forgive the parents for the divorce may help to restore and re-establish this relationship. This, in turn, may help children to adjustment to the divorce of their parents (e.g., Van der Wal et al. 2016). Conversely, children who tend to feel guilty for the divorce of their parents (e.g., Laumann-Billings & Emery, 2000), or hold in grief for the parents’ sake (e.g., Stroebe et al. 2013) may be at higher risk for post-traumatic symptoms. It would be interesting to examine whether processes such as forgiveness, feelings of guilt, or grief may help to gain a better understanding of differences in children’s adjustment following parental divorce. By combining self-report indices of children’s adjustment with open interviews, scholars will be better able to thoroughly examine individual differences in children’s adjustment to divorce.

The current article provides evidence of both risk and resilience in relation to children’s experience of their parents’ high-conflict divorce. Not only do they report high levels of divorce-related traumatic impact, on average, they also report relatively high levels of post-divorce adjustment. At the same time, children with more divorce-specific trauma reported less post-divorce adjustment. There may be important differences between children that contribute to these outcomes, and future research is needed to illuminate individual differences to explain the disparity in children’s reactions and experiences related to parental divorce.

References

Alisic, E., Zalta, A. K., van Wesel, F., Larsen, S. E., Hafstad, G. S., Hassanpour, K., & Smid, G. E. (2014). Rates of posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed children and adolescents: meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 204, 335–340.

Alisic, E., Van der Schoot, T. A., van Ginkel, J. R., & Kleber, R. J. (2008). Looking beyond posttraumatic stress disorder in children: Posttraumatic stress reactions, posttraumatic growth, and quality of life in a general population sample. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69, 1455–1461.

Allison, P. D., & Furstenberg, F. F. (1989). How marital dissolution affects children: Variations by age and sex. Developmental Psychology, 25, 540–549.

Amato, P. R. (2000). The consequences of divorce for adults and children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62, 1269–1287.

Amato, P. R. (2001). Children of divorce in the 1990s: an update of the Amato and Keith (1991) meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, 15, 355–370.

Amato, P. R. (2010). Research on divorce: Continuing trends and new developments. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 650–666.

Amato, P. R., & Afifi, T. D. (2006). Feeling caught between parents: Adult children’s relations with parents and subjective well‐being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 222–235.

Amato, P. R., & Keith, B. (1991). Parental divorce and adult well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 53, 43–58.

Anderson, S. R., Anderson, S. A., Palmer, K. L., Mutchler, M. S., & Baker, L. K. (2010). Defining high conflict. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 39, 11–27.

Association of Dutch Municipalities (2015). https://vng.nl/onderwerpenindex/maatschappelijke-ondersteuning/veilig-thuis-kindermishandeling-en-huiselijk-geweld/publicaties/factsheet-vechtscheidingen-feiten-en-cijfers

Belsky, J. (2008). War, trauma and children’s development: Observations from a modern evolutionary perspective. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 32, 260–271.

Benight, C. C., & Bandura, A. (2004). Social cognitive theory of posttraumatic recovery: The role of perceived self-efficacy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42, 1129–1148.

Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist, 59, 20–28.

Bonanno, G. A., & Diminich, E. D. (2013). Annual Research Review: Positive adjustment to adversity–trajectories of minimal–impact resilience and emergent resilience. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54, 378–401.

Booth, A., & Amato, P. R. (1994). Parental marital quality, parental divorce, and relations with parents. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 56, 21–34.

Brumley, L. D., & Jaffee, S. R. (2016). Defining and distinguishing promotive and protective effects for childhood externalizing psychopathology: A systematic review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51, 803–815.

Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (2016). Huwelijksontbindingen; door echtscheiding en door overlijden.

Cherlin, A. J. (1999). Going to extremes: Family structure, children’s well-being, and social science. Demography, 36, 421–428.

Cicchetti, D. (2010). Resilience under conditions of extreme stress: A multilevel perspective. World Psychiatry, 9, 145–154.

Davies, P. T., Sturge‐Apple, M. L., Winter, M. A., Cummings, E. M., & Farrell, D. (2006). Child adaptational development in contexts of interparental conflict over time. Child Development, 77, 218–233.

DeLucia-Waack, J. L., & Gellman, R. A. (2007). The efficacy of using music in children of divorce groups: Impact on anxiety, depression, and irrational beliefs about divorce. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 11, 272–282.

Dumont, M., & Provost, M. A. (1999). Resilience in adolescents: Protective role of social support, coping strategies, self-esteem, and social activities on experience of stress and depression. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 28, 343–363.

Dunn, J., Davies, L., O’Connor, T., & Sturgess, W. (2001). Family lives and friendships: The perspectives of children in step-, single-parent, and nonstop families. Journal of Family Psychology, 15, 272–28.

Ellis, B. J., Del Giudice, M., Dishion, T. J., Figueredo, A. J., Gray, P., & Griskevicius, V., et al. (2012). The evolutionary basis of risky adolescent behavior: Implications for science, policy, and practice. Developmental Psychology, 48, 598–623.

Fotheringham, S., Dunbar, J., & Hensley, D. (2013). Speaking for themselves: Hope for children caught in high conflict custody and access disputes involving domestic violence. Journal of Family Violence, 28, 311–324.

Flook, L., & Fuligni, A. J. (2008). Family and school spill over in adolescents’ daily lives. Child Development, 79, 776–787.

Frankenhuis, W. E., Panchanathan, K., & Nettle, D. (2016). Cognition in harsh and unpredictable environments. Current Opinion in Psychology, 7, 76–80.

Hardesty, J. L., Ogolsky, B. G., Raffaelli, M., Whittaker, A., Crossman, K. A., & Haselschwerdt, M. L., et al. (2017). Coparenting relationship trajectories: Marital violence linked to change and variability after separation. Journal of Family Psychology, 31, 844–854.

Harris, J. R. (1998). The nurture assumption. Why children turn out the way they do. New York: Free Press.

Hetherington, E. M. (1989). Coping with family transitions: Winners, losers, and survivors. Child Development, 60, 1–14.

Hetherington, E. M. (1991). The role of individual differences in family relations in coping with divorce and remarriage. In P. Cowan & E. M. Hetherington (Eds.), Advances in family research: Vol. 2. Family transitions (pp. 165–194). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Hetherington, E. M. (2006). The influence of conflict, marital problem solving and parenting on children’s adjustment in nondivorced, divorced and remarried families. In A. Clarke-Stewart & J. Dunn (Eds.), The Jacobs Foundation series on adolescence. Families count: Effects on child and adolescent development New York: Cambridge University Press, (pp. 203–237).

Hetherington, E. M., & Stanley-Hagan, M. (1999). The adjustment of children with divorced parents: A risk and resiliency perspective. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 40, 129–140.

Horowitz, M., Wilner, N., & Alvarez, W. (1979). Impact of Event Scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 41, 209–218.

Johnston, J. (1994). High-conflict divorce. The Future of Children, 4, 165–182.

Kelly, J. B. (2000). Children’s adjustment in conflicted marriage and divorce: A decade review of research. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 963–973.

Kelly, J. B., & Emery, R. E. (2003). Children’s adjustment following divorce: Risk and resilience perspectives. Family Relations, 52, 352–362.

Kuster, F., Orth, U., & Meier, L. L. (2013). High self-esteem prospectively predicts better work conditions and outcomes. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4, 668–675.

Lamb, M. E. (2012). Mothers, fathers, families, and circumstances: Factors affecting children’s adjustment. Applied Developmental Science, 16, 98–111.

Lansford, J. E. (2009). Parental divorce and children’s adjustment. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4, 140–152.

Lansford, J. E., Malone, P. S., Castellino, D. R., Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., & Bates, J. E. (2006). Trajectories of internalizing, externalizing, and grades for children who have and have not experienced their parents’ divorce. Journal of Family Psychology, 20, 292–301.

Laumann-Billings, L., & Emery, R. E. (2000). Distress among young adults from divorced families. Journal of Family Psychology, 14, 671–687.

Mann, M. M., Hosman, C. M., Schaalma, H. P., & De Vries, N. K. (2004). Self-esteem in a broad-spectrum approach for mental health promotion. Health Education Research, 19, 357–372.

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56, 227–238.

Masten, A. S. (2011). Resilience in children threatened by extreme adversity: Frameworks for research, practice, and translational synergy. Development and Psychopathology, 23, 493–506.

Masten, A. S., & Cicchetti, D. (2010). Developmental cascades. Development and Psychopathology, 22, 491–495.

Masten, A. S., & Narayan, A. J. (2012). Child development in the context of disaster, war, and terrorism: Pathways of risk and resilience. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 227–257.

Miller, G. E., Lachman, M. E., Chen, E., Gruenewald, T. L., Karlamangla, A. S., & Seeman, T. E. (2011). Pathways to resilience: Maternal nurturance as a buffer against the effects of childhood poverty on metabolic syndrome at midlife. Psychological Science, 22, 1591–1599.

Palosaari, U. K., & Aro, H. M. (1995). Parental divorce, self-esteem and depression: An intimate relationship as a protective actor in young adulthood. Journal of Affective Disorders, 35, 91–96.

Perrin, S., Meiser-Stedman, R., & Smith, P. (2005). The Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale (CRIES): Validity as a screening instrument for PTSD. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 33, 487–498.

Ravens-Sieberer, U., Erhart, M., Rajmil, L., Herdman, M., Auquier, P., & Bruil, J., et al. (2010). Reliability, construct and criterion validity of the KIDSCREEN-10 score: A short measure for children and adolescents’ well-being and health-related quality of life. Quality of Life Research, 19, 1487–1500.

Ravens-Sieberer, U., Horka, H., Illyes, A., Rajmil, L., Ottova-Jordan, V., & Erhart, M. (2013). Children’s quality of life in Europe: National wealth and familial socioeconomic position explain variations in mental health and wellbeing—A multilevel analysis in 27 EU countries. ISRN Public Health, 2013.

Robins, R. W., Hendin, H. M., & Trzesniewski, K. H. (2001). Measuring global self-esteem: Construct validation of a single-item measure and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 151–161.

Schoemaker, K., De Kruijff, A., Visser, M., Van Lawick, J., & Finkenauer, C. (2017). Vechtscheidingen: Beleving en ervaringen van ouders en kinderen en verandering na Kinderen uit de Knel. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit. Onderzoeksrapport.

Spruit, E., & Kormos, H. (2010). Handboek scheiden en de kinderen voor de beroepskracht die met scheidingskinderen te maken heeft. Houten: Bohn Stafleu Van Loghum.

Stroebe, M., Finkenauer, C., Wijngaards-de Meij, L., Schut, H., van den Bout, J., & Stroebe, W. (2013). Partner-oriented self-regulation among bereaved parents: The costs of holding in grief for the partner’s sake. Psychological Science, 24, 395–402.

Strohschein, L. (2005). Parental divorce and child mental health trajectories. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 1286–1300.

Sun, Y. (2001). Family environment and adolescents’ well‐being before and after parents’ marital disruption: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 697–713.

Sun, Y., & Li, Y. (2002). Children’s well‐being during parents’ marital disruption process: A pooled time‐series analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 472–488.

Tein, J. Y., Sandler, I. N., & Zautra, A. J. (2000). Stressful life events, psychological distress, coping, and parenting of divorced mothers: A longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology, 14, 27–41.

Thoits, P. A. (2010). Stress and health: Major findings and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(1 suppl.), S41–S53.

Van der Ploeg, E., Mooren, T., Kleber, R. J., van der Velden, P. G., & Brom, D. (2004). Construct validation of the Dutch version of the impact of event scale. Psychological Assessment, 16, 16–26.

Van der Wal, R. C., Karremans, J. C., & Cillessen, A. H. (2016). Interpersonal forgiveness and psychological well-being in late childhood. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 62, 1–21.

Van der Wal, R. C., Finkenauer, C., & Koelman, M. (2017). Van klacht naar kracht: Wanneer en hoe het empoweren van kinderen van gescheiden ouders bijdraagt aan een verhoogd welzijn. Onderzoeksrapport Niet Jouw Taak, Villa Pinedo.

Van Lawick, J., & Visser, M. (2015). No kids in the middle: Dialogical and creative work with parents and children in the context of high conflict divorces. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 36, 33–50.

Verlinden, E., Meijel, E. P., Opmeer, B. C., Beer, R., Roos, C., & Bicanic, I. A., et al. (2014). Characteristics of the children’s revised impact of Event Scale in a clinically referred Dutch sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27, 338–344.

Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Mac Iver, D., Reuman, D. A., & Midgley, C. (1991). Transitions during earlyadolescence: Changes in children's domain-specific self-perceptions and general self-esteem across thetransition to junior high school. Developmental Psychology, 27, 552–565.

Wolfinger, N. H. (2000). Beyond the intergenerational transmission of divorce: Do people replicate the patterns of marital instability they grew up with? Journal of Family Issues, 21, 1061–1086.

Wolfinger, N. H. (2005). Understanding the divorce cycle: The children of divorce in their own marriages. Cambridge University Press.

Zill, N., Morrison, D. R., & Coiro, M. J. (1993). Long-term effects of parental divorce on parent-child relationships, adjustment, and achievement in young adulthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 7, 91–103.

Author Contributions

R.W. analyzed the data and wrote the paper. C.F. collaborated with the design, collaborated in the writing and editing of the final manuscript. M.V. designed and executed the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee (provided by VU University Amsterdam) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

van der Wal, R.C., Finkenauer, C. & Visser, M.M. Reconciling Mixed Findings on Children’s Adjustment Following High-Conflict Divorce. J Child Fam Stud 28, 468–478 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1277-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1277-z