Abstract

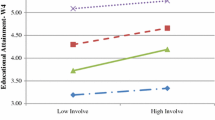

We investigated the direct and indirect pathways through which parental constructive behavior may influence the adolescent’s affiliation with achievement-oriented peers. Using a longitudinal survey data set from nine California and Wisconsin high schools (from 9th through 12th grades, with an approximate age range from 14 through 18) structural equation models were estimated. Our longitudinal analyses confirmed an indirect effect from Time 1 parental constructive behavior and a direct effect from Time 2 parental constructive behavior on an increase in the perceived achievement orientation of friends at Time 2, net of the stability effect from the prior values of the perceived achievement orientation of friends at Time 1. A point to be emphasized is that parental influence on peer affiliation in late adolescence remains significant even as parental involvement in adolescents’ lives diminishes. In addition, the direct effect from Time 2 parental constructive behavior on the perceived achievement-orientation of friends appears stronger for boys than for girls.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Astone, N. M., & McLanahan, S. S. (1991). Family structure, parental practices and high school completion. American Sociological Review, 56, 309–320.

Baharudin, R., & Luster, T. (1998). Factors related to the quality of the home environment and children’s achievement. Journal of Family Issues, 19, 375–403.

Bakan, D. (1966). The duality of existence: Isolation and communion in western man. Boston: Beacon Press.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Baumrind, D. (1968). Authoritarian versus Authoritative Parental Control. Adolescence, 3, 255–272.

Berndt, T. J. (1996). Transitions in Friendship and Friends’ Influence. In J. A. Graber, J. Brooks-Gunn, & A. C. Peterson (Eds.), Transitions through adolescence: Interpersonal domains and context (pp. 57–84). Mahwah, NJ, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Bijou, S. W., & Baer, D. M. (1961) Child development: A systematic and empirical theory (Vol. 1). New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Blake, J. (1989). Family size and achievement. Studies in demography, Vol. 3. Berkeley, CA, USA: University of California Press.

Bogenschneider, K., Wu, M., Raffaelli, M., & Tsay, J.C. (1998). Parent influences on adolescent peer orientation and substance use: The interface of parenting practices and values. Child Development, 69, 1672–1688.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1991). Discussant’s commentary. In S. Lamborn (Chair), Authoritative parenting and adolescent development. Symposium presented at the biennial meetings of the Society for Research in Child Development, Seattle.

Brown, B. B. (1990). Peer groups and peer cultures. In S. S. Feldman & G. R. Elliott (Eds.), At the Threshold: The developing adolescent (pp. 171–196). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Brown, B. B. (1996). Buzz off or butt in: Parental involvement in adolescent peer relationships. Symposium organized for the biennial meetings of the Society for Research on Adolescence, Boston, MA.

Brown, B. B., Mounts, N., Lamborn, S. D., & Steinberg, L. (1993). Parenting practices and peer group affiliation in adolescence. Child Development, 64, 467–482.

Chen, Z. (2000). The relationship between parental constructive behavior and the adolescent’s association with achievement oriented peers: A longitudinal study. Sociological Inquiry, 70, 360–381.

Coleman, J. C. (1980). Friendship and the peer group in adolescence. In J. Adelson (Ed.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 408–431). New York: Wiley.

Coleman, J. S. (1961). The adolescent society. New York: Free Press.

Conger, R. D. (1997). The social context of substance abuse: A developmental perspective. In E. B. Robertson, Z. Sloboda, G. M. Boyd, L. Beatty, & N. J. Kozel (Eds.), Rural substance abuse: State of knowledge and issues (NIDA research monograph 168: pp. 6–36). Rockville, MD, National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Corsaro, W. A., & Eder, D. (1990). Children’s peer cultures. Annual Review of Sociology, 16, 197–220.

Davies, M., & Kandel, D. B. (1981). Parental and peer influences on adolescents’ educational plans: Some further evidence. American Journal of Sociology, 87, 363–387

Demie, F. (2001). Ethnic and gender differences in educational achievement and implications for school improvement strategies. Educational Research, 43, 91–106.

Demo, D. H. (1992). Parent-child relations: assessing recent changes. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 54, 104–117.

Dornbusch, S. M., Ritter, P. L., Leiderman, P. H., Roberts, D. F., & Fraleigh, M. J. (1987). The relation of parenting style to adolescent performance. Child Development, 58, 1244–1257.

Durbin, D. L., Darling, N., Steinberg, L., & Brown, B. B. (1993). Parenting style and peer group membership among European-American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 3, 87–100.

Elder, G. H., Jr., Caspi, A., & Downey, G. (1986). Problem behavior and family relationships: Life-course and intergenerational themes. In A. M. Sorenses, F. E. Weiner, & L. R. Sherrod (Eds.), Human development and the life course: Multidisciplinary perspectives (pp. 293–342). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Everhart, R. (1983). Reading, writing and resistance: Adolescence and labor in a junior high school. Boston: Routledge.

Hanson, S. L. (1994). Lost talent: Unrealized educational aspirations and expectations among U.S. youths. Sociology of Education, 67, 159–183.

Haynie, D. L., & Osgood, D. W. (2005). Reconsidering Peers and Delinquency: How do Peers Matter? Social Forces, 84, 1109–1130.

Heaven, P. C. L., Ciarrochi, J., Vialle, W., & Cechavicuite, I. (2005). Adolescent peer crowd self-identification, attributional style and perceptions of parenting. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 15, 313–318.

Hinde, R. A., & Stevenson-Hinde, J. (Eds.). (1988). Relationships within families: Mutual influences. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press.

Hirschi, T. (1969). Causes of delinquency. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Joreskog, K. G., & Soerbom, D. (1993). Lisrel 8 user’s reference guide. Chicago: Scientific Software International.

Kandel, D. B. (1996). The parental and peer contexts of adolescent advance: an algebra of interpersonal influences. Journal of Drug Issues, 26, 289–315.

Ladd, G. (1992). Themes and theories: Perspectives on processes in family-peer relationships. In R. D. Parke & G. W. Ladd (Eds.), Family-peer relationships: Modes of linkage (pp. 3–34). Hillsdale, NJ, England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Licht, B. G., & Dweck, C. S. (1984). Determinants of academic achievement: the interaction of children’s achievement orientations with skill area. Developmental Psychology, 20, 628–636.

Melby, J. N., Conger, R. D., Conger, K. J., & Lorenz, F. O. (1993). Effects of parental behavior on tobacco use by young male adolescents. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 55, 439–454.

Mounts, N. S. (2000). Parental management of adolescent peer relationships: What are its effects on friend selection? In K. Kerns, J. Contreras, & Neal-Barnett (Eds.), Family and peers: Linking two social worlds (pp. 169–193). Westport, CT: Praeger.

Mounts, N. S. (2001). Young adolescents’ perceptions of parental management of peer relationships. Journal of Early Adolescence, 21, 92–122.

Mounts, N. S. (2002). Parental management of adolescent peer relationships in context: The role of parenting style. Journal of Family Psychology, 16, 58–69.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2004). Digest of education statistics (Table 169). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Newcomb, T. M. (1956). The prediction of interpersonal attraction. The American Psychologist, 11, 575–586.

Parke, R. D., & Buriel, R. (1998). Socialization in the family: Ethnic and ecological perspectives. In W. Damon (Series Ed.) & N. Eisenberg (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (5th ed., pp. 463–552). New York: Wiley.

Parke, R. D., & Ladd, G. W. (1992). Family-peer relationships: Modes of linkage. Hillsdale, NJ, England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Parke, R. D., MacDonald, K. B., Burks, V. M., Carson, J., Bhavnagri, N. P., Barth, J. M., et al. (1989). Family and peer systems: In search of the linkages. In K. Kreppner & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Family systems and life-span development (pp. 65–92). Hillsdale, NJ, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Patterson, G. R. (1996). Some characteristics of a developmental theory for early onset delinquency. In M. F. Lenzenweger & J. J. Haugaard (Eds.), Frontiers of developmental psychopathology (pp. 81–124). New York: Oxford University Press.

Patterson, G. R., DeBaryshe, B. D., & Ramsey, E. (1989). A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. Special Issue: Children and their development: Knowledge base, research agenda, and social policy application. American Psychologist, 44, 329–335.

Richards, M., & Larson, R. (1989). The life space and socialization of the self: Sex differences in the young adolescent. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 18, 617–626.

Rubin, Z., & Sloman, J. (1984). How parents influence their children’s friendships. In M. Lewis (Ed.), Beyond the dyad (pp. 115–140). New York: Plenum.

Ryan, A. M. (2001). The peer group as a context for the development of young adolescent motivation and achievement. Child Development, 72, 1135–1150.

Sameroff, A. J. (1983). Developmental systems: Contexts and evolution. In P. H. Mussen (series Ed.) & W. Kessen (Vol. Ed), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. History, theory and methods (pp. 237–294). New York: Wiley.

Scaramella, L. V., Conger, R. D., Spoth, R., & Simons, R. L. (2002). Evaluation of a social contextual model of delinquency: A cross-study replication. Child Development, 73, 175–195.

Schroeder, K. A., Blood, L. L., & Maluso, D. (1992). An intergenerational analysis of expectations for women’s career and family roles. Sex Roles, 26, 273–291.

Sewell, W. H., & Hauser, R. M. (1980). The Wisconsin longitudinal study of social and psychological factors in aspirations and achievements. In A. C. Kerckjoff (Ed.), Research in sociology of education and socialization (Vol. 1, pp. 59–99). Greenwich, Conn: JAI Press.

Stockard, J., & Wood, J. W. (1984). The myth of female underachievement: A reexamination of sex differences in academic underachievement. American Educational Research Journal, 21, 825–838.

Tilton-Weaver, L. C., & Galambos, N. L. (2003). Adolescents’ Characteristics and Parents’ Beliefs as Predictors of Parents’ Peer Management Behaviors. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 13, 269–300,

Updegraff, K. A., McHale, S. G., Grouter, A. C., & Kupanoff, K. (2001). Parents’ involvement in adolescents’ peer relationships: A comparison of mothers’ and fathers’ roles. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 63, 655–668.

Vernberg, E. M., Beery, S. H., Ewell, K. K., & Abwender, D. A. (1993). Parents’ use of friendship facilitation strategies and the formation of friendships in early adolescence: A prospective study. Journal of Family Psychology, 7, 356–369.

Youniss, J., & Smollar, J. (1985). Adolescent relations with mothers, fathers, and friends. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Acknowledgment

Preparation of this article was supported by Mini Grants, Summer Research Fellowships and Professional Development Grants to Zeng-yin Chen from California State University-San Bernardino. The study on which this article is based was supported by grants to Sanford M. Dornbusch and P. Herbert Leiderman from the Spencer Foundation and the Carnegie Foundation of New York, and to Laurence Steinberg and B. Bradford Brown from the U.S. Department of Education, through the National Center on Effective Secondary Schools at the University of Wisconsin—Madison.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Measurements of endogenous variables

Appendix: Measurements of endogenous variables

Parental Constructive Behavior (T1/T2): (Latent construct with four additive indexes) Monitoring (alpha = .80/.81):

How much do your parents REALLY know … (Answering categories: 1 = Don’t know, 2 = Know a little, 3 = Know a lot.)

-

Who your friends are?

-

Where you go at night?

-

How you spend your money?

-

What you do with your free time?

-

Where you are most afternoons after school?

Involvement (alpha = .71/.73):

How much are your mother and father involved in your high school education? (Answering categories: 1 = Never, 2 = Sometimes, 3 = Usually.)

(Note: Students answered the question for mother, father, stepmother and stepfather separately, and the index takes on the highest score among the four possible parents.)

-

Helps with homework when I ask.

-

Makes sure I do home work.

-

Checks my homework over.

-

Knows how I’m doing in school.

-

Goes to school programs for parents.

-

Helps me in choosing my courses.

Spend time together (alpha = .71/.68):

How often do these things happen in your family? (Answering categories: 1 = Almost every day, 2 = A few times a week, 3 = A few times a month, 4 = Almost never. Reverse coded.)

-

My parents spend time just talking with me.

-

My family does something fun together.

-

My parent(s) eat the evening meal with me.

-

My parent(s) are home in the evening with me.

Family functionally organized (alpha = .77/.73):

How much do you agree or disagree with these statements? (Answering categories: 1 = Strongly agree, 2 = Agree somewhat, 3 = Disagree somewhat, 4 = Strongly disagree. Reverse coded.)

-

In my family, we check in or out with each other when someone leaves or comes home.

-

Our family is pretty organized.

-

My family has certain routines that help our household run smoothly.

Education Orientation (T1/T2): (Latent construct with two indicators)

Educational expectations (single-item indicator):

Considering your situation, what is the highest level that you really expect to go in school? (Answering categories: 1 = Leave school as soon as possible, 2 = Finish high school, 3 = Get some vocational or college training, 4 = Finish a two-year community college degree, 5 = Finish college with a four-year college degree, 6 = Finish college and take further training.)

Homework (alpha = .79/.78):

For each class, how much do you currently put into homework each week, including reading assignments: (Answering categories: 1 = None, 2 = About 15 min, 3 = About 30 min, 4 = About an hour, 5 = About 2 or 3 hr, 6 = About 4 hours or more.

-

Math.

-

English.

Perceived Achievement Orientation of Friends (T1/T2): (Latent construct with four single-item indicators)

Among the friends you hang out with, how important is it to: (Answering categories: 1 = Extremely important, 2 = Pretty important, 3 = Sort of important, 4 = Not at all important. Reverse coded.)

-

Get good grades.

-

Be involved in school activities

-

Finish high school

-

Continue your education past high school

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Zy., Dornbusch, S.M. & Liu, R.X. Direct and Indirect Pathways between Parental Constructive Behavior and Adolescent Affiliation with Achievement-Oriented Peers. J Child Fam Stud 16, 837–858 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-006-9129-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-006-9129-7