Abstract

Although the Artist’s Contract, first developed in 1971, was not broadly adopted in its early decades, renewed interest in it fifty years later has led to inventive related structures that are enabled by blockchain technology, in particular the phenomenon of NFT (non-fungible token) sales in art. We argue that the Contract’s conceptual roots have laid groundwork for a potentially powerful funding mechanism via the Contract’s resale royalties terms. Blockchain technology radically alters risks of incomplete contracting and lowers transaction costs, making the Quixotic terms of the Artist’s Contract newly actionable. We study the artist Hans Haacke’s longtime experimentation with the Artist’s Contract, along with contemporary data from the blockchain registry SuperRare, which pays royalties to artists. Blockchain companies such as SuperRare generally sell digital works outside the taste-making and gatekeeping systems of the upper echelons of the traditional art market. This arc from conceptual practice within the arts to commercial practice at the edge of the traditional art market points to the Contract’s legacy as a model for potentially disruptive technology and a new fundraising model for artists.

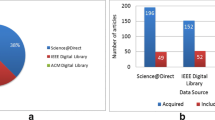

Source: Franceschet (2020)

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

Our data are not publicly available, though SuperRare shares with researchers who may wish to contact the firm for other projects.

Notes

These contracts date back to the early 1900s in France when André Level’s Peau de L’Ours (Bearskin) club, recognized as the first art-buying syndicate, shared resale proceeds with artists after their 1914 sale at the Hôtel Drouot in Paris (FitzGerald 1996: 16). The proceeds to artists constituted a substantial, e.g., 20%, share of the artists’ annual wage (FitzGerald 1996: 44).This sharing of proceeds with artists took place six years before French law came to require resale royalties or droit de suite to be shared back to artists (FitzGerald 1996: 17). The Hôtel Drouot sale brought 116,545 francs ($44,535 in 2020 dollars). Pablo Picasso’s (1881–1973) twelve works in the sale accounted for 31,201 francs, of which 3,979 francs was shared with Picasso; that amount represented 20% of the profits above the artworks’ acquisition costs and made up 20% of Picasso’s recorded income for the year 1914 (FitzGerald 1996: 44, 276, 278). Even artists who did not receive large payments wrote thank you letters to Level (FitzGerald 1996: 44).

The contract also granted artists copyright protections, moral rights, the right to a portion of rental fees when the work is loaned to exhibition, the right to borrow their work, and other economic rights in their works.

Royalty payments following the California Resale Royalty Act were not closely monitored. The only available data reflects payments made by sellers who reverted funds to the California Arts Council for disbursement. There are no public data on royalty payments made by individual sellers.

His institutional impact includes a scheduled retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum in 1971 which was cancelled owing to Haacke’s artworks investigating the actions of New York City slumlords and other social-political issues (Deutsche 1986). Haacke received subsequent retrospectives at the New Museum in 1986 and 2019, in addition to numerous major exhibitions in Europe.

There is little consistency among auction records in terms how the Artist’s Contract is noted, and sometimes it is not mentioned in auction listings for affected works at all (van Haaften-Schick 2020). Haacke has also emphasized that his ability to secure a teaching job early in his career gave him financial security to refuse certain buyers. He was able to use the Artist’s Contract because he never relied on art sales for his income and as such was willing to risk alienating buyers and dealers. (Eichhorn 2009: 74).

Whitaker and Kräussl (2020) have proposed retained fractional equity as a privately contracted alternative to resale royalties, with artists “purchasing” the equity in foregone primary-market proceeds, circumventing arguments made my scholars such as Rub (2014; Sprigman and Rub 2018) that royalties constitute a special class of welfare to artists. The work is divisible as property so that the rights persist after first sale (Hansmann and Kraakman 2002).

Whitaker and Kräussl (2020) have shown that if various mid-twentieth-century US artists had retained equity in their work they would have outperformed US equities markets substantially.

Potts et al., (2008) have proposed “social network markets” as a framing device, characterizing creative industries as both market-driven and dependent on networked relationships, emphasizing Granovetter’s (1985) concept of embeddedness of markets within social structures. Social networks have also been applied to crowdfunding, though some scholars have critiqued crowdfunding for potentially accidentally replacing public funding with a neoliberal logic (Brabham 2016). At the same time, public funding in the USA often comes under threat by conservative administrations, and the administrative requirements and legal structures that art organizations must adopt in order to qualify for most public funding, such as 501(c)(3) non-profit status, can also force them to adopt that neoliberal logic regardless (Wallis 2002). Models of financial reliance on artists’ resale royalties and retained equity could fall prey to this criticism as well.

Within the visual arts’ current diffusion of registrarial systems, there is no centralized database of museum collections or gallery inventories; certificates of authenticity can be lost or forged; incomplete provenance records can make sales and authentication impossible; and the only public sale data is that from auction houses, leaving a huge percentage of private and gallery transactions unaccounted for and difficult to retrace. Blockchain-based approaches have numerous use cases. Yet these systems also contend with art’s illiquidity as an asset, the industry’s aversion to transparency (Velthuis and Coslor 2012), and the difficulty obtaining price information (Velthuis 2005: 166). Opacity especially governs the secondary art market, where auction houses and dealers protect the identities of buyers so that even artists do not know who owns their works. The Artist’s Contract was in part designed to mitigate these problems by requiring sellers to inform the artist of the sale price and the identity of the new owner whenever works are sold or ownership is transferred, serving its own vetting function.

Monegraph uses Ethereum as a layer-one blockchain protocol in tandem with Polygon, a layer-two protocol.

For early entrants to SuperRare, the royalty rate was 10%; it is now 3% (Author correspondence Charles Crain, SuperRare, November 2020).

Also employing smart contracts to secure resale royalties was the Calgary-based Uppstart, founded in 2018 and dormant at time of publication, offered a 4% resale royalty via self-executing smart contract (Addapcity, Inc., 2018).

Proof of work (PoW) and proof of stake (PoS) are two different methods of verifying new blocks that are added to a blockchain. In the Proof of Work system, computers compete to solve brute computer processing puzzles with the winner receiving cryptocurrency. This method is especially criticized for consuming power and therefore damaging the environment (Kahn 2021). Ethereum network has announced its intentions to move from proof of work to proof of stake with its launch of Eth2 (Ethereum.org 2021a; 2021b).

The blockchain ventures also hold numerous similarities, for instance, employing some kind of physical tagging technology, such as RFID tags, QR codes, and synthetic DNA.

Artory’s system maintains an immutable record of every event in the lifecycle of an artwork, such as a sale or valuation request. When a new record is created, it is given a timestamp that can be located on Artory’s Ethereum-based blockchain. In 2021, Artory announced a move to the Algorand blockchain (Artory 2021). This system offers a secure register of when each record was entered, “with a goal of providing greater confidence in an artwork’s ongoing provenance and greater efficiency in its eventual resale” (Artory 2018). In November 2018, Christie’s auction house held the first sale wherein all works sold were registered on Artory’s Ethereum blockchain. That sale, the Barney A. Ebsworth Collection, brought $318 million (Elhanani 2018).

Counteracting these limitations of art as illiquid and private-value asset, Maecenas has worked by tokenizing art (called the ART token) to convert blue chip artworks into smaller financial units that can be bought and sold as digital certificates, or securities. Investors can then resell them via the Maecenas exchange (Maecenas 2020).

These blockchain companies offering fractional ownership in art are contextualized by a broad literature on studies of the returns to investment in art. Baumol (1986) found returns similar to corporate bonds with higher volatility (Renneboog and Spaenjers 2013; Burton and Jacobson 1999). These studies have drawn primarily on repeat sales methods (e.g., Goetzmann, 1993; Mei and Moses 2002, 2005) and hedonic regression or mixed methods (e.g., Renneboog and Spaenjers 2013; Korteweg et al. 2016). Further studies have identified significant variation in returns across works within a sample (Spaenjers et al., 2015) and high transaction costs (Ashenfelter and Graddy 2003).

Precedents for clarifying these exist in the analog art world. For example, certain ephemeral art forms such as performance and idea-based conceptual artworks are readily acquired by museums via certificates of authenticity and other forms of documentation, so that while there is no tangible art object to own, and anyone could hypothetically execute the work, such works are nonetheless able to be exclusively owned and command substantial prices via certificates or contract-like paperwork (Abrams & Whitaker 2021; Buskirk 2003).

The Contract was designed to be revised by artist users, and terms could be waived. Levy and others have argued that the very nature of technologically self-executing contracts does not allow for interpersonal exchange, negotiation, and for consensual non-enforcement (Levy 2017), which legal realists have long-held are important aspects of the sociality of contracts (Macaulay 1963; Macneil 1978). As such these technologies may not capture the bond between artists and collectors that the Artist’s Contract anticipated (Library Stack 2017). Siegelaub’s goal for artists to keep “aesthetic and exhibition control” remains to be tested, by technologies that could be built to retain relationality without sacrificing the economic and enforcement benefits of automation.

It would remain to be determined whether those investment trusts included artists as currently defined or a broader realm of visual and cultural producers.

We use the pre-pandemic market report, which shows the relatively stable size of the art market prior to COVID.

The Artist’s Contract exposes the previous selling price when works are resold, though Siegelaub and Projansky were aware that the actual price paid might not be recorded on the contract (Siegelaub and Projansky 1971: 3).

References

Abbing, H. (2002). Why Are Artists Poor? Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Abrams, N.B. & Whitaker, A. (2021, April 22). NFTs: WTF?An illuminating program about non-fungible tokens. Denver, CO: Museum of Contemporary Art Denver [video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qi8NHe2PJvc

Adam, G. (2020, March 20). From hot new thing to ‘cryptowinter’ chill: Sizing up fractional ownership of art. The Art Newspaper. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2020/03/20/from-hot-new-thing-to-cryptowinter-chill-sizing-up-fractional-ownership-of-art

Addapcity, Inc. (2018, June 24). “UppstArt app pays resale royalties to emerging artists with blockchain technology.” Cision. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/uppstart-app-pays-resale-royalties-to-emerging-artists-with-blockchain-technology-300685396.html

Artory. (2021, November 25). Artory partners with Algorand. The Artory Blog. https://www.artory.com/blog/artory-partners-with-algorand/.

Artory. (2018). Artory collaborates with Christie’s on an industry first: Registration of major art collection. Medium. https://medium.com/artory/artory-collaborates-with-christies-on-an-industry-first-registration-of-major-art-collection-5228ed94a567

Arts Council England, TBR, a-n The Artists Information Company & Doeser, J. (2018). Livelihoods of Visual Artists: Literature and Data Review. https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/download-file/Livelihoods%20of%20Visual%20Artists%20Literature%20and%20Data%20Review.pdf

Ashenfelter, O., & Graddy, K. (2003). Auctions and the price of art. Journal of Economic Literature, 41(3), 763–786.

Banternghansa, C., & Graddy, K. (2011). The impact of the “Droit de Suite” in the UK: An empirical analysis. Journal of Cultural Economics, 35(2), 81–100.

Baumol, W. (1986). Unnatural value: Or art investment as floating crap game. American Economic Review, 76(2), 10–14.

Becker, H. S. (2008). Art worlds (25th anniversary ed., updated and expanded.). University of California Press.

Bianco, P. (2019). The Droit De Suite or resale royalty right under the Brazilian framework. IIC – International Review of Intellectual Property and Competition Law, 50, 196–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40319-019-00784-2.

Block, J. H., Colombo, M. G., Cumming, D. J., & Vismara, S. (2018). New players in entrepreneurial finance and why they are there. Small Business Economics, 50(2), 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9826-6

Brabham, D. C. (2016). How crowdfunding discourse threatens public arts. New Media & Society, 19(7), 983–999.

Bradley, C. G., & Frye, B. L. (2019). Art in the age of contractual negotiation. Kentucky Law Journal, 107(4), 2.

Brunton, F. (2019). Digital cash: The unknown history of the anarchists, utopians, and technologists who created Cryptocurrency. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Burton, B. T., & Jacobsen, J. P. (1999). Measuring returns on investments in collectibles. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 13(4), 193–212.

Catlow, R., Garrett, M., Jones, N., & Skinner, S. (Eds.). (2017). Artists re:thinking the blockchain. Torque Editions, Furtherfield

Caves, R. E. (2003). Contracts between art and commerce. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(2), 73–84.

Caves, R. E. (2000). Creative industries: Contracts between art and commerce. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Childress, C., Baumann, S., Rawlings, C., & Nault, J.-F. (2021). Genres, objects, and the contemporary expression of higher-status tastes. Sociological Science, 8, 230–264. https://doi.org/10.15195/v8.a12

Chow, A. R. (2021, March 22). NFTs are shaking up the art world: But they could change so much more. Time Magazine. https://time.com/5947720/nft-art/.

Christensen, C. (1997). The Innovator’s Dilemma. Cambridge: Harvard Business Review.

CleanNFTS. (2021, December 9). CleanNFTS. https://cleannfts.org/

Coase, R. H. (1960). The problem of social cost. Journal of Law and Economics, 3(October), 1–44.

Coase, R. H. (1937). The nature of the firm. Economica, 4(16), 386–405.

Cohen, P. (2011, Nov 1). Artists file lawsuits, seeking royalties. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/02/arts/design/artists-file-suit-against-sothebys-christies-and-ebay.html

Colonna, C. M., & Colonna, C. G. (1982). An economic and legal assessment of recent visual artists’ reversion rights agreements in the United States. Journal of Cultural Economics, 6(2), 77–85.

Creative Independent. (2018). A study of the financial state of visual artists today, available at: https://thecreativeindependent.com/artist-survey/.

DACS. (2018). Annual review 2018. Available at: https://www.dacs.org.uk/DACSO/media/DACSDocs/DACS-Annual-Review-2018.pdf.

DACS. (2019, unpublished). Artists and the art market: Survival and success, Internal DACS unpublished report.

De Leon, J. M. (2020). Philippines: Enriching the lives of artists in the Philippines through the use of the resale right. Mondaq. https://www.mondaq.com/copyright/981186/enriching-the-lives-of-artists-in-the-philippines-through-the-use-of-resale-right

Dekker, E. (2015). Two approaches to study the value of art and culture, and the emergence of a third. Journal of Cultural Economics, 39, 309–326.

del Pesco, J. (2020, July 27). How a new kind of Artist’s Contract could provide a simple, effective way to redistribute the art market’s wealth. Artnet News. https://news.artnet.com/opinion/resale-royalties-contract-kadist-joseph-del-pesco-1897169

Deutsche, R. (1986). Property values: Hans Haacke, real estate, and the museum. In B. Wallis (Ed.), Hans Haacke: Unfinished Business (pp. 20–37). Cambridge: MIT Press and New Museum of Contemporary Art.

Eichhorn, M. (2009). The Artist’s Contract (G. Fietzek, Ed.). Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König.

Elhanahi Z. (Dec. 17, 201). How blockchain changed the art world in 2018. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/insights-inteliot/2018/11/29/intels-sameer-sharma-makes-a-brilliant-case-for-the-smart-city/?sh=332008a165cd

Espeland, W. N., & Stevens, M. L. (1998). Commensuration as a social process. Annual Review of Sociology, 24, 313–333. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.313

Essig, L. (2014). Arts incubators: A typology. The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society, 44, 169–180.

Ethereum.org. (2021a, September 12). ERC-721 non-fungible token standard. https://ethereum.org/en/developers/docs/standards/tokens/erc-721/

Ethereum.org. (2021b, December 9). The Eth2 upgrades. https://ethereum.org/en/eth2/

Farchy, J. & Graddy, K. (2017, November 6). The economic implications of the artist’s resale right, Standing Committee on Copyright and Related Rights, Thirty-Fifth Session Geneva, November 13 to 17, 2017, World Intellectual Property Organization. https://www.wipo.int/edocs/mdocs/copyright/en/sccr_35/sccr_35_7.pdf.

Feldman, F., & Weil, S. E. (1974). Droit de Suite. In Art Works: Law, Policy, Practice (pp. 81–97). Practising Law Institute.

Finley, C., van Haaften-Schick, L., Reeder, C., & Whitaker, A. (2021, November 22). The recent sale of Amy Sherald’s ‘Welfare Queen’ symbolizes the Urgent Need for Resale Royalties and Economic Equity for Artists,” ArtNet News, November 22, 2021. https://news.artnet.com/opinion/amy-sheralds-welfare-queen-resale-royalties-economic-equity-artists-2037904.

Fitzgerald, M. C. (1996). Making modernism: Picasso and the creation of the market for twentieth-century art. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Fourcade, M. (2011). Cents and sensibility: Economic caluation and the nature of ‘nature.’ American Journal of Sociology, 116(6), 1721–1777. https://doi.org/10.1086/659640

Franceschet, M. (2020). Primary and secondary markets in crypto art. http://users.dimi.uniud.it/~massimo.franceschet/ns/plugandplay/challenges/dada/dada.html

Franco, M., Haase, H., & Correia, S. (2018). Exploring factors in the success of creative incubators: A cultural entrepreneurship perspective. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 9(1), 239–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-015-0338-4

Frey, B. S., & Jegen, R. (2001). Motivation crowding theory. Journal of Economic Surveys, 15(5), 589–611.

Gerber, A., & Childress, C. (2017). I don’t make objects, I make projects: Selling things and selling selves in contemporary artmaking. Cultural Sociology, 11(2), 234–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975517694300

Glucksman, C. P. (1982). Art resale royalties: Symbolic or economic relief for the fine artist. Cardozo Arts & Entertainment Law Journal, 1, 115–136.

Glueck, G. (1969, April 6). Peepshows and put-ons. New York Times, D24.

Goetzmann, W. N. (1993). Accounting for taste: Art and financial markets over three centuries. American Economic Review, 83(5), 1370–1376.

Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic actions and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481–510.

Greenfield, A. (2018). Radical technologies: The design of everyday life. London: Verso.

Grimmelmann, J. (2019). All smart contracts are ambiguous. Journal of Law & Innovation, 2(1), 1–22.

Guadamuz, A. (2020). Smart contracts and intellectual property: Challenges and reality. In C. Heath, A. K. Sanders, & A. Moerland (Eds.), Intellectual Property and the 4th Industrial Revolution. Amsterdam: Kluwer International Law.

van Haaften-Schick, L. (2018). Conceptualizing artists’ rights: Circulations of the Siegelaub-Projansky Agreement through art and law. Oxford: Oxford Handbooks Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935352.013.27

van Haaften-Schick, L. (2020). Subversion in the fine print: ‘The Artist’s Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement’ at auction, The College Art Association Annual Conference, Chicago, IL. February 12–15, 2020.

van Haaften-Schick, L. (2021). Remedies for inequity 1971–2021: Resale royalties to redistribution. Working with Intellectual Property: Legal Histories of Innovation, Labor, and Creativity. Stanford Center for Law and History, Stanford Law School, Palo Alto, CA. April 23, 2021.

Haber, S., & Stornetta, W. S. (1991). How to time-stamp a digital document. Journal of Cryptology, 3(2), 99–111.

Hansmann, H., & Kraakman, R. (2002). Property, contract, and verification: The numerus clausus problem and the divisibility of rights. Journal of Legal Studies, 31(S2), 373–420.

Hiscox. (2020). Hiscox Online Art Trade Report 2020: Part One: . https://www.hiscox.co.uk/sites/uk/files/documents/2020-07/Hiscox_online_art_trade_report_2020-new.pdf

Hiscox. (2021). Hiscox Online Art Trade Report 2020. Part Three: Towards a Frictionless Online Journey. https://www.hiscox.co.uk/sites/default/files/documents/2021-04/hoatr_report_2020_part3.pdf

Hutter, M., & Throsby, C. D. (2008). Beyond Price: Value in Culture, Economics, and the Arts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Johnson, J. B. (1992). Copyright: Droit de Suite: An artist is entitled to royalties even after he’s sold his soul to the devil. Oklahoma Law Review, 45, 493–518.

Kadist.org. (2019). Artist contract. https://kadist.org/program/artist-contract/

Kahn, B. (2021, March 10). How to fix crypto art NFTs’ carbon pollution problem. Gizmodo. https://gizmodo.com/how-to-fix-crypto-art-nfts-carbon-pollution-problem-1846440312

Karpik, L. (2010). Valuing the unique: The economics of singularities. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kawashima, N. (2008). The artist’s resale right revisited: A new perspective. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 14(3), 299–313.

Kee, J. (2019). Models of integrity: Art and law in post-sixties America. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Khaire, M. (2017). Culture and commerce: The value of entrepreneurship in creative careers. Redwood City: Stanford University Press.

Kinsella, E. (2020, August 13). Speculation on Black artists has gotten so intense that for Christie’s latest sale, its curator is asking buyers to sign a special contract. Artnet News. https://news.artnet.com/market/say-loud-show-christies-1901685.

Korteweg, A., Kräussl, R., & Verwijmeren, P. (2016). Does it pay to invest in art? A selection-corrected returns perspective. Review of Financial Studies., 29(4), 1007–1038.

Kräussl, R. (2013). The death effect? Not so fast. Databank. Art +Auction, 2013(6):154–155.

Kusin & Co. (2005). The Global Market for Modern and Contemporary Art: 2002–2004. https://www.kusin.com

Leaffer, M. A. (1989). Of moral rights and resale royalties: The Kennedy bill. Cardozo Arts & Entertainment Law Journal, 7(227), 234–248.

Lessig, L. (1999). Code and other laws of cyberspace. New York: Basic Books.

Levy, K. E. C. (2017). Book-smart, not street-smart: Blockchain-based smart contracts and the social workings of law. Engaging Science, Technology, and Society, 3, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.17351/ests2017.107

Stack, L. (2017). Cloudism library stack on blockchain Archives and library futures. Texte Zur Kunst, 108, 183–189.

Macaulay, S. (1963). Non-contractual relations in business: A preliminary study. American Sociological Review, 28(1), 55–67. https://doi.org/10.2307/2090458

MacDonald-Korth, D., Lehdonvirta, V., & Meyer, E. T. (2018). The Art Market 2.0: Blockchain and Financialisation in Visual Arts. University of Oxford and The Alan Turing Institute.

MacFarquhar, L. (2012, May 7). When giants fail. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2012/05/14/when-giants-fail

Macneil, I. R. (1978). Contracts: Adjustment of long-term economic relations under classical, neoclassical, and relational contract law. Northwestern University Law Review, 72(854), 854–905.

McAndrew, C. (2020). The Art Market Report 2020. UBS and Art Basel.

McNamara, R. (2021, March 2). How crypto-art might offer artists increased autonomy. Hyperallergic. https://hyperallergic.com/626274/nft-crypto-art-artist-autonomy/

Mei, J., & Moses, M. (2002). Art as an investment and the underperformance of masterpieces. American Economic Review, 92(5), 1656–1668.

Mei, J., & Moses, M. (2005). Vested interest and biased price estimates: Evidence from an auction market. Journal of Finance, 60(5), 2409–2435.

Merryman, J. H. (1992). The wrath of Robert Rauschenberg. (Artists’ resale proceeds right). Journal of the Copyright Society of the u.s.a, 40(2), 241–264.

Milgrom, P. R., & Roberts, J. (1992). Economics, organization, and management. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Monegraph. (2015) Terms of service. http://www.monegraph.com/

NAWC to Issue New Contract. (1971). Art Workers Newsletter, 1(3), 4.

New York Herald Tribune. (1939, December 31). Wood to share resale profits on his painting: Iowa artist starts plan with “Parson Weems” fable, his first oil in 3 years. New York Herald Tribune, 12.

Nickson, J. W., & Colonna, C. M. (1977). The economic exploitation of the visual artist. Journal of Cultural Economics, 1(1), 75–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02479726

NiftyGateway. (2021). “Work With Us To Create And Sell Your Own Nifties.” https://niftygateway.com/become-creator

O’Dair, M. (2019). Distributed creativity: How blockchain technology will transform the creative economy. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

O’Dair, M., & Owen, R. (2019). Monetizing new music ventures through blockchain: Four possible futures? The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 20(4), 263–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465750319829731

OpenSea. (2021, December 9). “How do royalties work on OpenSea? https://support.opensea.io/hc/en-us/articles/1500009575482-How-do-royalties-work-on-OpenSea-

Penasse J, Renneboog L, Scheinkman J (2020). When a master dies: Speculation and asset float. Preprint, February 28, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3385460.

Petterson, A. & Cocksey, J. (2021, November). NFT art market report. ArtTactic. https://arttactic.com/product/nft-art-market-report-november-2021/

Potts, J., Cunningham, S., Hartley, J., & Ormerod, P. (2008). Social network markets: A new definition of the creative industries. Journal of Cultural Economics, 32(3), 167–185.

Price, M. E., & Brown Price, A. (1971). Rights of artists: The case of the Droit de Suite. Art Journal, 31(2), 144–149.

Renneboog, L., & Spaenjers, C. (2013). Buying beauty: On prices and returns in the art market. Management Science, 59(1), 36–53.

Rodrigues, U. R. (2019). Law and the blockchain. Iowa Law Review, 104, 679–729.

Rub G.A. (2014). The unconvincing case for resale royalties. Yale Law Journal Forum, Accessed January 7, 2018, https://www.yalelawjournal.org/forum/the-unconvincing-case-for-resale-royalties.

Rushton, M. (1999). Methodological individualism and cultural economics. Journal of Cultural Economics, 23, 137–146.

Schneider, T. (2018, March 22). Cryptocurrencies, explained: How blockchain technology could solve 3 big problems plaguing the art industry. Artnet News. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/cryptocurrencies-explained-part-three-1248863

Samuelson, P. A. (1954). The pure theory of public expenditure. The Review of Economics and Statistics., 36(4), 387–389.

Schneider, T. (2021a, September 30). The duo that invented the art world’s first crypto platform in 2014 is back with a tool to help galleries launch their own NFT marketplaces. Artnet News. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/monegraph-nft-ecommerce-platform-2015338

Schneider, T. (2021b, March 11). Will NFTs revolutionize the art market or repeat its greatest failures? Artnet News. https://news.artnet.com/market/nft-revolution-four-factors-1950645.

Schten, A. (2017). No more starving artists: Why the art market needs a universal artist resale royalty right. Notre Dame Journal of International & Comparative Law, 7(1), 115–137.

Scott, R. E., & Triantis, G. (2005). Incomplete contracts and the theory of contract design. Case Western Law Review, 56(1), 187–201.

Shaw, A. (2018, July 23). Will blockchain deliver a registry of all traded works of art? The Art Newspaper. http://theartnewspaper.com/news/will-blockchain-deliver-a-registry-of-all-traded-works-of-art

Siegelaub, S. (1970). Draft questionnaire to artists, 15 December 1970. Seth Siegelaub papers [I.A.90]. Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. https://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2013/siegelaub/images/contract.jpg.

Siegelaub, S., & Projansky, R. (1971). The Artist’s Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement. School of Visual Arts, New York. https://primaryinformation.org/product/siegelaub-the-artists-reserved-rights-transfer-and-sale-agreement/

Sigurdardottir, M. S., & Candi, M. (2019). Growth strategies in creative industries. Creativity and Innovation Management, 28(4), 477–485. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12334

Simon, H. A. (1996 [1969]). The Sciences of the Artificial, (3rd ed). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Simon, H. (1957). Models of Man. New York: Wiley.

Spaenjers, C., Goetzmann, W. N., & Mamonova, E. (2015). The economics of aesthetics and record prices for art since 1701. Explorations in Economic History, 57(1), 79–94.

Sprigman, C., & Rub, G. (2018, August 8). Resale royalties would hurt emerging artists. Artsy. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-resale-royalties-hurt-emerging-artists

Strada, A. (2017). The Artist’s Contract. http://alexstrada.com/contract.html

SuperRare. (2021, November 22). Terms of service: Ownership of a SuperRare item. https://www.notion.so/SuperRare-Terms-of-Service-075a82773af34aab99dde323f5aa044e

SuperRare. (2020, April 2). SuperRare turns two!. Medium. https://medium.com/superrare/superrare-turns-two-6e4226a094ad

Thill, V. (2020, June 10). New artist resale rights contract in the US has a charitable twist. The Art Newspaper. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/new-artist-resale-rights-contract-in-the-us-has-a-charitable-twist

Towse, R. (2017). Economics of music publishing: Copyright and the market. Journal of Cultural Economics, 41(4), 403–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-016-9268-7

Tresise, A., Goldenfein, J., & Hunter, D. (2018). What Blockchain Can and Can’t Do for Copyright. Australian Intellectual Property Journal, 28, 144–157.

United States Copyright Office. (2013). Resale royalties: An updated analysis. Washington, D.C.: Office of the Register of Copyrights. https://www.copyright.gov/docs/resaleroyalty/usco-resaleroyalty.pdf

Valverde, M. (2012). Everyday law on the street: City governance in an age of diversity. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Vartanian, H. (2014, April 23). NEWD Art fair set to open during 2014 Bushwick Open Studios. Hyperallergic. https://hyperallergic.com/122259/newd-art-fair-set-to-open-during-2014-bushwick-open-studios/

Velthuis, O. (2005). Talking prices: Symbolic meanings of prices on the market for contemporary art. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Velthuis, O. (2011). The Venice effect. The Art Newspaper, 20(225), 21–24.

Verstraete, M. (2019). The stakes of smart contracts. Loyola University Chicago Law Journal, 50(3), 743–795.

Vickers, C. M. (1980). The applicability of the Droit de Suite in the United States. Boston College International and Comparative Law Review, 3(2), 433–466.

Wallis, B. (2002). Public funding and alternative spaces. In J. Ault (Ed.), Alternative art, New York, 1965–1985: A cultural politics book for the Social Text Collective (pp. 161–182). Minneapolis: Drawing Center; University of Minnesota Press.

Waugh, M. (2018). We owe artists the crucial income resale royalties provide. Artsy. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-owe-artists-crucial-income-resale-royalties-provide

Werbach, K. (2018). Trust, but verify: Why the blockchain needs the law. Berkeley Technology Law Journal, 33(2), 489–552.

Whitaker, A. (2014). Ownership for artists. In P. Helguera, M. Mandiberg, W. Powhida, A. Whitaker, & C. Woolard (Eds.), The social life of artistic property (pp. 100–121). Hudson: Publication Studio.

Whitaker, A. (2018). Artist as owner not guarantor: The art market from the artist’s point of view. Visual Resources, 34(1–2), 48–64.

Whitaker, A. (2019a). Art and blockchain: A primer, history, and taxonomy of blockchain use cases in the arts. Artivate: A Journal of Entrepreneurship in the Arts, 8(2), 21–46.

Whitaker, A. (2019b). Shared value over fair use: Technology, added value, and the reinvention of copyright. Cardozo Art and Entertainment Law Journal, 37(3), 635–657.

Whitaker, A. (2021). Economies of scope in artists’ incubator projects. Journal of Cultural Economics, 45, 613–631.

Whitaker, A., & Grannemann, H. (2019). Artists’ royalties and performers’ equity: A ground-up approach to social impact investment in creative fields. Cultural Management, 3(2), 33–51.

Whitaker, A., & Greenland, F. (2021). What do the Inigo Philbrick scandal and the NFT craze have in common? The can help us rebuild the art market. Artnet News. https://news.artnet.com/opinion/op-ed-nft-inigo-philbrick-1982353.

Whitaker, A., & Kräussl, R. (2020). Fractional equity, and the future of creative work. Management Science, 66(10), 4594–4611.

Whitaker, A., & Kräussl, R. (2018). Artists are entrepreneurs. We should compensate them accordingly. Artsy. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-artists-entrepreneurs-compensate

Wilkerson, M. (2012). Using the arts to pay for the arts: A Proposed new public funding model. Journal of Arts Management, Law and Society, 42(3), 103–115.

Williamson, O. E. (1985). The economic institutions of capitalism: Firms, markets, relational contracting. New York: Free Press.

Acknowledgements

Lauren van Haaften-Schick acknowledges the Smithsonian Institution Predoctoral Fellowship program and the Engelberg Center on Innovation Law and Policy at New York University Law School for support. The authors thank John Crain and Charles Crain of SuperRare, Kevin McCoy of Monegraph, and Anne Bracegirdle, as well as Massimo Franceschet for generously sharing formatted data files.

Funding

Funding for this study was received from the Smithsonian Institution Predoctoral Fellowship program and the Engelberg Center on Innovation Law and Policy at New York University Law School (van Haaften-Schick).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: selected droit de suite/resale royalties legislation

Appendix: selected droit de suite/resale royalties legislation

Country or Jurisdiction | Royalty Rate | Threshold (minimum sales price) | Cap (maximum royalty) | Sales Covered | Term | Mechanisms of Collection and Enforcement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

European Union | < € 50,000 = 4% or 5% 50,001 to € 200,000 = 3% 200,001 to € 350,000 = 1% 350,000 to € 500,000 = 0.5% above € 500,000 = 0.25% | € 3,000.00 | € 12,000 | Resale in which "art market professionals" are buyers, sellers, or intermediaries | Copyright term | Paid by the seller member states can specify other payer rights holder has rights to sales information |

UK | Same as European Union | $1,000.00 | Same as EU | Resale in which buyer, seller, or agent "is acting in the course of a business dealing with works of art" | Copyright term | Compulsory collective management (DACS) seller, buyer, and agent have joint and several liability rights holder has rights to sales information |

Australia | 5% of the total resale price | AUD $1,000 | "Commercial resale involving art market professional" | Copyright term | Compulsory collective management seller, buyer, and agent have joint and several liability royalty due is treated as a debt to the rights holder possible civil and criminal enforcement | |

Brazil | 5% of any gain in value | No minimum if sold for a gain | Resale "of original work of art or manuscript" | Life of the author plus 20 years for artists who die after January 1, 1983 | Seller or auctioneer, if any, is considered the depositary of the royalty if the author does not collect it at the time of sale | |

India | Not to exceed 10% of the resale price, as set by the Copyright Board | 10,000 rupees | Resale | Copyright term | Disputes referred to the Copyright Board | |

Kenya | 5% of the net sale price on the commercial resale of an artwork | KES 20,000 and above | Does not apply to works sold for charitable purposes, architectural drawings and models, or manuscripts | Copyright term | The seller, the art market professional, the seller's agent and the buyer shall be jointly and severally liable to pay the resale royalty | |

Philippines | < 150,000 PhP = 5% 150,001 to 350,000 = 4% 350,001 to 600,000 = 3% 600,000 to 1,000,000 = 2% 1,000,001 to 2,000,000 = 1.5% above 2,000,000 = 1% | none | "resale or lease subsequent to first disposition by the author" | Life of the author plus 50 years | ||

USA Proposed 2011 | 7% of the resale price | $10,000 | Resale in an auction by someone other than the artist | Copyright term | Compulsory collective management Seller is liable for the royalty Remedies include suit for copyright infringment and statutory damages | |

Proposed 2018 | 5% of the resale price | $5,000 | $35,000 | Resale in an auction by someone other than the artist | Copyright term | Compulsory collective management Seller is liable for the royalty Remedies include suit for copyright infringment and statutory damages |

California, USA | 5% of the resale price | $1000 gross sales price, if price is higher than purchase | "Resale at auction, or by a gallery, dealer, broker, museum, or other person acting as seller's” | Life of the author plus 20 years for artists who die after January 1, 1983 | Optional collective management Seller or agent liable California Arts Council manages for unlocated artists remedies include damages, legal fees, and fines |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van Haaften-Schick, L., Whitaker, A. From the Artist’s Contract to the blockchain ledger: new forms of artists’ funding using equity and resale royalties. J Cult Econ 46, 287–315 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-022-09445-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-022-09445-8