Abstract

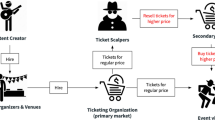

The fair price ticketing curse occurs when an event organizer sells tickets at prices that do not correspond to underlying demand conditions and does not want resellers to profit from resale opportunities. The curse has been exacerbated with the advent of online ticketing. The challenge is to facilitate genuine ticket exchange while eliminating resale for profit. None of the attempted public or private solutions solve the problem. We propose a simple mechanism, identify a key set of necessary conditions for it to work, and discuss recent technological innovations that facilitate its implementation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This problem has not been addressed in past studies of resale (Courty 2003a, b; Cui et al. 2014). See also Christian Hassold’s Ticket Economist (http://ticketeconomist.com/scholarly/).

Other problems with primary and secondary markets that have been discussed in recent policy reports (Waterson 2016; Schneiderman 2016; US Government Accountability Office 2018) include: (a) lack of transparency in primary markets, with use of pre-sales and holds, and manipulation of prices and supply by the event organizer or ticketing agent. We revisit this issue in the conclusion and argue that these practices would diminish with our solution to the FPTC. (b) Deceptive websites that mimic the official vendor and charge inflated prices.

The Schneiderman report (2016), which has investigated many events taking place in New York, documents how brokers use bots (see Sect. A.2).

Obviously, the argument is flawed because resellers do not reduce the number of seats available for fans.

In one instance, he canceled 10 K tickets that were selling eight times above face value. He returned these tickets to fans. At the face value of €86, this corresponds to a €6 million transfer that went back and forth from scalpers to fans. This is the tip of the iceberg. There were problems with resale in most countries he visited.

A notorious exception is the Wimbledon queue (https://www.wimbledon.com/en_GB/atoz/queueing.html).

Even when a concert or sporting event is sold out, the President of StubHub, Chris Tsakalakis, reports that about 5–10% of the people don’t show up (http://www.huffingtonpost.com/chris-tsakalakis/why-reselling-tickets-is_b_643219.html).

Although unusual, the assumption that fans do not anticipate future prices, resale opportunities and cancelation possibility, is not entirely unrealistic in the context of our application. It is consistent with the puzzle that fans rarely resell tickets for profits (Krueger 2001) and with evidence from the airline industry that few travelers are forward looking (Li et al. 2014).

This is a rough attempt at capturing the distinction between fans and brokers. Some fans spend time and often fail to acquire a ticket because bots have an advantage. This welfare cost, which is not taken into account here, would further reinforce the conclusion that resale markets are not always optimal.

Brokers contribute to welfare by allocating tickets to high valuation consumers. Other arguments in support of brokers, not modeled here, are that they add liquidity and help with the price discovery process.

For free events, ticket holders would be charged a small deposit that would be refunded when they return the ticket or attend the event.

StubHub charge 25% per ticket exchange while the fan-to-fan Twickets platform charges 10%. Part of this difference is because integrating the sponsored fan-to-fan exchange with the primary market eliminates disputes, misrepresentation and fraud.

In the USA, the Better online Ticket Sales (BOTS) Act of 2016 makes it illegal for bots to purchase tickets or to resell tickets that were bought by bots. England has amended the Consumer Right Act in 2015 and introduced the Digital Economy Act in 2017.

One rare exception is NY’s $7.1 million fines settlement with brokers following the Schneiderman inquiry.

As a gesture to its public, he offers about 50 premium seats for $10 on a lottery basis, which when valued at $1000 per seat, amounts to a $50 K gift per show.

For example, a CE can deal with groups by assigning a probability to be served that decreases with the size of the group. As a shortcoming, a CE would have difficulties managing ticket transfers to family and friends. Allowing such transfers would be costly to manage because it would require human verification.

References

Bhave, A., & Budish, E. (2017). Primary-market auctions for event tickets: Eliminating the rents of’bob the broker’? New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Courty, P. (2003a). Some economics of ticket resale. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(2), 85–97.

Courty, P. (2003b). Ticket pricing under demand uncertainty. The Journal of Law and Economics, 46(2), 627–652.

Courty, P. (forthcoming). In P. Downward, B. Frick, B. R. Humphreys, T. Pawlowski, J. E. Ruseski, & B. P. Soebbing (Eds.), Secondary ticket markets for sport events. The SAGE handbook of sports economics. Beverley Hills: Sage.

Courty, P., & Pagliero, M. (2013). In V. Ginsburgh & T. Throsby (Eds.), The pricing of art and the art of pricing: Pricing styles in the concert industry. Handbook of the economics of art and culture (Vol. 2, pp. 299–356). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Cui, Y., Duenyas, I., & Şahin, Ö. (2014). Should event organizers prevent resale of tickets? Management Science, 60(9), 2160–2179.

Drayer, J. (2011). Examining the effectiveness of anti-scalping laws in a united states market. Sport Management Review, 14(3), 226–236.

Elfenbein, D. W. (2006). Do anti-ticket scalping laws make a difference online? Evidence from internet sales of NFL tickets. Working paper.

Happel, S. K., & Jennings, M. M. (1995). The folly of anti-scalping laws. Cato Journal, 15, 65.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. (1986). Fairness as a constraint on profit seeking: Entitlements in the market. The American Economic Review, 76(4), 728–741.

Krueger, A. B. (2001). Supply and demand: An economist goes to the super bowl and he got to deduct it. Milken Institute Review, 3, 22–29.

Leslie, P., & Sorensen, A. (2014). Resale and rent-seeking: An application to ticket markets. Review of Economic Studies, 81(1), 266–300.

Li, J., Granados, N., & Netessine, S. (2014). Are consumers strategic? Structural estimation from the air-travel industry. Management Science, 60(9), 2114–2137.

Moore, D. (2009). The times they are a changing: Secondary ticket market moves from taboo to mainstream. Texas Review of Entertainment & Sports Law, 11, 295.

Roth, A. E. (2007). Repugnance as a constraint on markets. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(3), 37–58.

Sandel, M. J. (2012). What money can’t buy: The moral limits of markets. New York: Macmillan.

Schneiderman, E. (2016). Obstructed view: What’s blocking New Yorkers from getting tickets. http://www.ag.ny.gov/pdfs/Ticket_Sales_Report.pdf. Accessed 3 May 2019.

Sweeting, A. (2012). Dynamic pricing behavior in perishable goods markets: Evidence from secondary markets for major league baseball tickets. Journal of Political Economy, 120(6), 1133–1172.

Tunçel, T., & Hammitt, J. K. (2014). A new meta-analysis on the WTP/WTA disparity. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 68(1), 175–187.

US Government Accountability Office. (2018). Event ticket sales: Market characteristics and consumer protection issues. Government Accountability Office 18-374.

Waterson, M. (2016). Independent review of consumer protection measures concerning online secondary ticketing facilities. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/consumer-protection-measures-applying-to-ticket-resale-waterson-review. Accessed 3 May 2019.

Waterson, M. (2018). Ticketing as if consumers mattered. Warwick Economic Research Papers 1177.

Acknowledgements

The Author would like to thank Daniel Rondeau and seminar participants at the University of Victoria for useful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Proof of Proposition 1

We have \(\frac{d}{d \beta } W_{{\mathrm{RM}}}=\overline{V}K \left( \delta _{{\mathrm{v}}} - \tau (\beta ) - (1-\alpha ) (\delta _{{\mathrm{v}}}- \tilde{\tau }) + \beta \tau '(\beta ) \right)\). \(\frac{d}{d \beta } W_{{\mathrm{RM}}}<0\) is equivalent to \(\tau (\beta )- \delta _{{\mathrm{v}}} > -\beta \tau '(\beta ) + (1-\alpha ) (\tilde{\tau }-\delta _{{\mathrm{v}}})\). To demonstrate that this inequality holds, observe that: (1) \(\tau (\beta )- \delta _{{\mathrm{v}}} > 0\) under free entry and Assumption 1; (2) the first term on the right hand side, \(-\beta \tau '(\beta )\), is negative; and (3) to deal with the second term consider two possibilities. If \(\delta _{{\mathrm{v}}} \ge \tilde{\tau }\), this term is negative and the inequality holds. If \(\tilde{\tau } \ge \delta _{{\mathrm{v}}}\), the inequality is a consequence of \(\tau (\beta ) \ge \tilde{\tau }\). □

Proof of Proposition 2

RM dominates CE if and only if

which simplifies to

This inequality always hold when \(\delta _{{\mathrm{v}}}-\tau (\beta ) \ge \frac{1-\alpha }{\alpha } (\tau (\beta )-\tilde{\tau })\). When this is not the case, that is \(\delta _{{\mathrm{v}}}-\tau (\beta )< \frac{1-\alpha }{\alpha } (\tau (\beta )-\tilde{\tau })\), RM dominates CE for any value of \(\beta\) if \(\beta _{{\mathrm{CE,RM}}}>1\) which is equivalent to \(\delta _{{\mathrm{v}}}-\tau (\beta )>-(1-\alpha ) \tilde{\tau }\). Since \(\frac{1-\alpha }{\alpha } (\tau (\beta )-\tilde{\tau })>-(1-\alpha )\tilde{\tau }\), we conclude that RM dominates CE for any value of \(\beta\) when \(\delta _{{\mathrm{v}}} - \tau (\beta ) >-(1-\alpha )\tilde{\tau }\). This establishes claim (1a) in Proposition 2.

When \(\delta _{{\mathrm{v}}} - \tau (\beta ) <-(1-\alpha )\tilde{\tau }\), RM dominates CE when \(\beta <\beta _{{\mathrm{CE,RM}}}\) and CE dominates RM otherwise. This, together with the definition of \(\beta _{{\mathrm{RM,RB}}}\) establishes claims (1b), (2) and (3) in Proposition 2. □

1.1 Analysis of CE

The CE mechanism has four features (see Table 2, Column 1): (RfR) refund for return, (RA) random reallocation of returned tickets, (L) ledger of current legitimate owner, and (ID) check at admission that identification of ticket holder matches the name on ledger. We compare the CE with a situation where all these features are not implemented jointly. When a feature is not implemented, we assume that the default feature presented in Column 2 applies. For example, fans are not refunded anything instead of RfR (line 1), returned tickets are unused instead of RA (line 2), and so on...Clearly, other default options than those presented in Column 2 could be considered. Since the point is to demonstrate the importance of the four design features of a CE, we select defaults used in practice.

Some of these measures have been implemented separately but never together with one exception. As mentioned in Sect. 4, some artists have used multiple technologies to match identity at admission (feature 4), Twickets reallocates returned tickets (feature 2), and some startups (Blocktix, BitTicket) offer block chain technologies for ticket exchange that allow to track-and-trace the ownership chain (feature 3). However, we argue that these measures alone do not solve the problems of no-shows and resale for profit.

The timing of events goes as follows: (1) the event organizer announces which of the four design features are implemented. A default feature applies when a design feature is not selected. (2) Fraction \(\beta\) of tickets are bought by brokers. (3) Fraction \(1-\beta\) of remaining tickets are randomly distributed to fans. (4) Fans find out whether they can attend the event: Fraction \(\alpha (1-\beta ) \frac{K}{N}\) of fans own a ticket and can attend, \((1-\alpha )(1-\beta )\frac{K}{N}\) own a ticket and cannot attend, \(\alpha \left( 1- (1-\beta ) \frac{K}{N} \right)\) do not have a ticket and can attend. (5) Brokers post price \(p_{{\mathrm{r}}}>p_0\). (6) Fans may buy tickets from brokers, sell tickets in RM, or return tickets if this option is available. The cost of reallocating a ticket within CE is \(\tilde{\tau }\). (7) Tickets are redeemed. A ticket bought in RM does not entitle admission when L and ID apply.

Proposition 3

\(W_{{\mathrm{RM}}}=\overline{V} K \left( 1-\tilde{\tau }(1-\alpha ) \right)\)if and only if\(({\mathrm{RfR}}, {\mathrm{RA}}, L, {\mathrm{ID}})\)are implemented.

When \(({\mathrm{RfR}}, {\mathrm{RA}}, L, {\mathrm{ID}})\) are implemented no broker enter: (1) \(\beta =0\), (2) fraction \(1-\alpha\) of tickets are resold, (3) all tickets are used, and (4) the average valuation among users is \(\overline{V}\). We have \(W_{{\mathrm{RM}}}=K \overline{V} \left( 1-\tilde{\tau }(1-\alpha ) \right)\).

Next, we show that welfare changes if all four components of a CE are not present together. We consider here eliminating a single feature at a time, keeping in mind that the argument generalizes when multiple features are eliminated jointly: (a) when RfR is not implemented, fans do not return tickets and welfare is \(\alpha K \overline{V}\); (b) when RA is not implemented, returned tickets are unused and we have again that welfare is equal to \(\alpha K \overline{V}\); (c) when L is not implemented but ID is, reallocated tickets cannot be redeemed. Welfare is \(\alpha K \overline{V}\); (d) when ID is not implemented, we are back to the RM outcome. This concludes the proof.

Ed Sheeran has come closest to a CE for his 2018 tour.Footnote 23 A shortcoming of his scheme is that each buyer can purchase up to four tickets and only the identity of the buyer is checked at admission.Footnote 24 Scalpers have arranged to enter the venue with those who purchase their extra tickets. But the take away is that the basic building block necessary to implement a CE is available and has been used. Achieving the desired outcome is just a matter of implementing the different building blocks together.

To conclude, we consider a fan-to-fan face exchange (FtF) because it has been used in practice. Doing so also clarifies the role of random reallocation in CE. FtF has the RfR feature but the difference is that the other features do not apply. Implemented alone, FtF does not deter brokers from reselling tickets in RM. To make the argument more interesting, assume that FtF is implemented along with L and ID. This does not achieve the first best outcome because brokers are not deterred. Brokers can benefit by selling at face value on FtF in order to make sure that the buyer is the new legitimate owner on the ledger (recall that L and ID apply) conditional on receiving a side payment from the buyer. Such side payments would be difficult to detect and punish. It is now clear why random reallocation of returned tickets (RA) is necessary to deter broker entry.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Courty, P. Ticket resale, bots, and the fair price ticketing curse. J Cult Econ 43, 345–363 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-019-09353-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-019-09353-4