Abstract

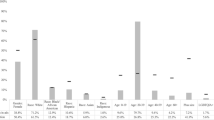

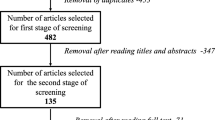

The value of a painting is influenced above all by the artist who created it and his reputation. Painters nowadays are easy to identify and are used to signing their artworks. But what about those whose names have not survived the test of time? This paper contributes to the understanding of art valuation and art brands on the auction market. It focuses on a particular subset of anonymous artists labelled with so-called provisional names (“Master of …”). After considering the origins and reception of the practice of creating names for unrecorded artists, we empirically investigate the market behaviour of this niche segment. Based on comparative price indexes and hedonic regressions, we show that masters with provisional names have not only become autonomous brand names that are highly valued by the art market; they also outperformed named artists between 1955 and 2015. In the second phase, we analyse the provisional-name linked elements valued by the market. We find that art market participants pay attention to the creator of the provisional name, its long-term recognition and market visibility, and the typology of the names.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See The Master of the Plump-Cheeked Madonna (active in Bruges, first quarter of the sixteenth century), The Virgin and Child with Saints Dominic, Augustine, Margaret and Barbara, Christie’s Rockefeller Plaza (New York), Renaissance (sale 2819), 29 January 2014, lot 105. Presale estimate: USD 400,000—USD 600,000.

According to Turner (1996, p. 611), anonymous masters should not be confused with named artist with the prefixed title “Master” and no surname, as in Master Bertram.

Young British Artists.

Note that the concept of petit maîtres remains debated since it is unclear whether their anonymity is due to their poor skills or to our current misunderstanding of their art (Bücken and Steyaert 2013, p. 6).

Some authors however disagreed with this concept. Wilenski (1960, p. XI;12) criticizes the use of provisional names based on style ascription, claiming that they confuse rather than clarify, and recommends maintaining the anonymity of unrecorded artists.

One of the main reasons is that Beazley’s system of attribution was highly criticized by one of his colleagues and rivals, Edmond Pottier, curator at the Louvre (Rouet 2001). On the contrary, Friedländer’s provisional names did not face such radical opposition.

Provenance information affords evidence of previous appearances of these paintings on the art market (see for example, De Vos 1969, pp. 219–301).

Based on a sample of 200 sales catalogues recorded in the Rijksbureau voor Kunst Documentie’s collection (The Hague), the INHA (Institut Nationale d’Histoire de l’art, Paris), and the Getty Provenance Index database.

American Art Galleries, Highly Important Collection of Ancient Painting, 18 January 1918 (lots 70 and 56).

In his prologue, Châtelet (1996) provides a historiographical synthesis on this controversial issue. Foister and Nash’s contribution results from a symposium that took place at the National Gallery in 1996. In their study, greater attention is paid to scientific investigations and technical analyses, but their conclusions still reflect the difficulty of concluding on a definitive identification. As pointed out by Campbell (1998, p. 72) “The painter of the “Flémalle” panels has much in common with Jacques Daret and Rogier van der Weyden and has therefore been identified as their teacher Robert Campin. It must be stressed however that there is no general agreement on this identification”.

Hulin de Loo and Friedländer died in 1945 and 1958, respectively.

This is the case, for example, of the Master of 1473, a Bruges master whose unique reference painting is a triptych entitled The Triptych of Jean de Witte, purchased by the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium through the Brussels-based gallery Robert Finck in 1963.

Born between 1390 and 1568 and active in the Southern Low Countries.

Initially our sample accounts for 874 observations from which buy-ins were excluded. The Master of the Double Portrait of Cleveland and the Master of 1521 have been intentionally omitted from the sample because there is no firm evidence of their official recognition by the academic field and they might therefore be a salesroom’s invention.

e.g. Master of the Saint Lucia Legend—Master of the Legend of Saint Lucy—Master of the Saint Lucy Legend—Maître de la Légende de sainte Lucie.

There is a large literature about the fifteenth- and sixteenth-century workshop system and authenticity issues raised by such mechanism of production. A lot of paintings were produced under the name of the master who ran the workshop, while the identity of his pupils, assistants, journeymen and other executants was not meant to be divulgated. Nowadays, original and autograph paintings by the master are viewed as high-quality paintings while those executed by anonymous hands, from models provided by the master, usually have a lower symbolic and monetary value. Scientific technologies of investigation have played a major role in the differentiation of those hands.

Under the category “Identified masters”, we include not only autograph paintings but all the works attached to the name of identified masters with attribution qualifiers (“attributed to”, “studio of”, “circle of”, “follower of”, etc.).

Similarly, the category “Master with provisional names” includes pictures attached to the name of these masters with attribution qualifiers.

And even this might be disputed. If one imagines a buyer with no art history knowledge, a name such as Lichtenstein could be associated to central Europe or Germany rather than to the USA.

Artist’s names (in the case of unidentified masters, the paintings were sorted on the basis of the artistic school they belong to: Flemish, Antwerp, Brussels, etc.), attribution qualifiers (except for unidentified masters), date, signature, provenance, certificate, previous exhibition, existing literature, dimensions (height and width), materials, techniques, subjects, salesrooms, years. Most of these controls (except dimensions) are dummy variables that take the value 1 if the condition is satisfied or 0 otherwise.

Most famous names have been confirmed by Ginsburgh and Weyers (2006, p. 24) who demonstrated that they were amongst the most sustainable and acknowledged names throughout art history.

Master of the Parrot-0.858*; Master of the 1540s-1.189**; Master of Delft-1.144*; Master of the Antwerp Crucifixion-1.339; Master of the Legend of Saint Barbara 1.521**; Master of the Amsterdam Death of the Virgin-1.559**; Master of the Baroncelli Portraits 2.575***; Master of the Prodigal Son-1.525***. Note that most negative coefficients are related to the sixteenth-century masters, while rarer fifteenth-century artists have mostly positive coefficients.

We conducted several interviews in 2017 in London-based art galleries and salesrooms specialized in the market for Old Masters.

Most of the names created by Friedländer are logically found in his book (with the exception of the Master of the Gold Brocade), but are also included in Thieme & Becker and the Grove Dictionary of Art. Inclusion generates collinearity with the other variable “By Friedländer”. Indeed, 89% of observations are attributed to provisional names included in Die Altniederländische Malerei, 708 are attributed to provisional names mentioned in Thieme & Becker, and 661 observations are attributed to provisional names recorded in the Grove Dictionary of Art.

Most of other variables remain robust when the Art Dictionaries variable is excluded from the model.

These occasional cases do not seem to affect our results (cf. The Master of the Plump-Cheeked Madonna).

Nonetheless, references to prestigious and well-known collectors could obviously add value to a brand name, especially about provenance.

A third option would have been to include a binary variable for every creator, but with several cases of unique sales, this would have led to collinearity issues.

In total, 59 lots ascribed to The Master of 1518 are detected after 1966 in our sample. Concerning the simultaneous use of both names, see for example: Jan van Dornicke, formerly known as The Master of 1518, Triptych with the Adoration of the Magi, Nativity and Flight into Egypt, Sotheby’s York Avenue (New York), Important Old Master Paintings and Sculpture, 28 January 2010, lot 152. That some scholars and museums still leave this identification open is one possible reason for mitigating this behaviour (Born 2010).

References

Aaker, D. A. (1992). The value of brand equity. Journal of Business Strategy, 13(4), 27–32.

Aaker, J. (1997). Dimensions of brand personality. Journal of Marketing Research, 34(3), 347–356.

Ainsworth, M. (1998). The business of art: patrons, clients and art markets. In M. Ainsworth & K. Christiansen (Eds.), From Van Eyck to Bruegel: early Netherlandish painting in the metropolitan museum of art (pp. 23–39). New York: Metropolitan Museum.

Ainsworth, M. W. (2005). From connoisseurship to technical art history. The Evolution of the Interdisciplinary Study of Art. The Getty Conservation Institute Newsletter (vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 4–10).

Akerlof, G. A. (1970). The market for ‘Lemons’: quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84(3), 488–500.

Ashenfelter, O., & Graddy, K. (2003). Auctions and the price of art. Journal of Economic Literature, 41(3), 763–787.

Baumol, W. J. (1986). Unnatural value: or art investment as floating crap game. American Economic Review, 76(2), 10–14.

Beazley, J. D. (1925). Attische Vasemaler des rotfigurigen Stils. Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr.

Beckert, J., & Rössel, J. (2013). The price of art. European Societies, 15(2), 178–195.

Berenson, B. (1957-1968). Italian Pictures of the Renaissance. Florentine school, 2 vol.; Venetian school, 2 vol., Central Italian and North Italian school, 3 vol., London: Phaidon.

Biglaiser, G. (1993). Middlemen as experts. The Rand Journal of Economics, 24(2), 212–223.

Born, A. (2010), Essai d’analyse critique du maniérisme anversois de Max Jacob Friedländer suivi d’une révision du groupe des œuvres du Maître de 1518 (Jan Mertens van Dornicke?), Ph.D. dissertation, Universiteit Gent, 2010.

Bücken, V., & Steyaert, G. (2013). L’héritage de Rogier van der Weyden. La peinture à Bruxelles 1450–1520. Brussels: Brepols.

Campbell, L. (1976). The art market in the Southern netherlands in the fifteenth century. The Burlington Magazine, 118, 188–198.

Campbell, L. (1998). The fifteenth century Netherlandish paintings. London: National Gallery.

Carroll, J. M. (1981). Creating names for things. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 10(4), 441–455.

Castelnuovo, E. (1968). Attribution. Encyclopaedia Universalis, 2, 780–783.

Chastel, A. (1974). Signature et signe. Revue de l’art, 26, 12–24.

Châtelet, A. (1996). Robert Campin - Le maître de Flémalle. La fascination du quotidien. Anvers: Fonds Mercator.

Coffman, R. B. (1991). Art investment and asymmetrical information. Journal of Cultural Economics, 15(2), 83–94.

De Vos, D. (1969). Primitifs flamands anonymes: catalogue avec supplément scientifique. Maîtres aux noms d’emprunt des Pays-Bas méridionaux du XVe et du début du XVIe siècle, cat. exp., 11 June – 21 September 1969, Lannoo: Tielt.

Dubin, J. A. (1998). The demand for branded and unbranded products—An econometric method for valuing intangible assets. In J. A. Dubin (Ed.), Studies in consumer demand econometric methods applied to market data (pp. 77–127). New York: Springer.

Eichenberger, R., & Frey, B. S. (1995). On the rate of return in the art market: survey and evaluation. European Economic Review, 39(3–4), 528–537.

Foister, S., & Nash, S. (1996). Robert Campin: New directions in scholarship. London: National Gallery.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Boston: Pittman.

Friedländer, M. J. (1903). Die Brügger Leihausstellung von 1902. Repertorium für Kunstwissenschaft LXVI, S. 148ff.

Friedländer, M. J. (1915). Die Antwerpener Manieristen von 1520. Jahrbuch der königlich preußischen Kunstsammlungen, 36, 65–91.

Friedländer, M. J., (1924-1937). Die Altniederlandische Malerei. 14 vol., Berlin: Cassirer. (English ed. (1967-1976). Early Netherlandish Painting. New York: Frederick A. Praeger).

Friedländer, M. J. (1942). On art and connoisseurship. Boston: Beacon Press.

Galvagno, M., & Dalli, D. (2014). Theory of value co-creation: a systematic literature review. Managing Service Quality, 24(6), 643–683.

Ginsburgh, V., Mei, J., & Moses, M. (2006). The computation of price indices. In V. Ginsburgh & D. Throsby (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of arts and culture (pp. 947–979). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Ginsburgh, V., Schwed, N. (1992). Price Trends for Old Master’s Drawings 1980–1991. The Art Newspaper.

Ginsburgh, V., & Weyers, S. (2010). On the formation of canons: The dynamics of narratives in art history. Empirical Studies of the Arts, 28, 37–72.

Goetzmann, W. N. (1993). Accounting for taste: Art and the financial markets over three centuries. American Economic Review, 83(5), 1370–1376.

Goetzmann, W. N. (1995). The informational efficiency of the art market. Managerial Finance, 21(6), 25–34.

Gombert, F., & Martens, D. (dir.) (2007). Le Maître au feuillage brodé. Démarche d’artistes et méthodes d’attribution d’œuvres à un peintre anonyme des anciens Pays-Bas du XVe siècle, conference proceedings: Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille 23-24 June 2005.

Gombert, F., & Martens, D. (2005). Primitifs flamands. Le Maître au Feuillage brodé. Secrets d’ateliers, cat. exp. (Palais des Beaux-arts de Lille: 13 May– 24 July 2005), Lille, 2005.

Grampp, W. (1989). Pricing the priceless. Art, artists and economics. New York: Basic Books.

Haskell, F. (1976). Rediscoveries in art: Some Aspects of taste, fashion and collecting in England and France. New-York: Cornell University Press.

Henderiks, V. (2016). L’anonymat dans la peinture flamande du XVe siècle. Des maîtres aux noms d’emprunt aux collaborateurs d’atelier. In S. Douchet & V. Naudet (Eds.), L’anonymat dans les arts et les lettres au Moyen Âge (pp. 95–105). Aix en Provence: Presses de l’université de Provence.

Hernando, E., & Campo, S. (2017). Does the artist’s name influence the perceived value of an art work? International Journal of Arts Management, 19(2), 46–58.

Hoeffler, S., & Keller, K. L. (2002). Building brand equity through corporate societal marketing. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 21(1), 78–89.

Holt, D. B. (2004). How brands become icons. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School.

Hook, P. (2013). Breakfast at Sotheby’s. London: Penguin Books.

Hulin de Loo, G. (1902). De l’identité de certains maîtres anonymes. Gand: A. Siffer.

Jones, S. F. (2011). Van Eyck to Gossaert: Towards a northern Renaissance. London: National Gallery.

Karababa, E., & Kjeldgaard, D. (2013). Value in marketing: Toward sociocultural perspectives. Marketing Theory, 14(1), 119–127.

Karpik, L. (2010). Valuing the unique. The economics of singularities. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57, 1–22.

Kerrigan, F., Brownlie, D., Hewer, P., & Daza-LeTouze, C. (2011). Spinning” Warhol: Celebrity brand theoretics and the logic of the celebrity brand. Journal of Marketing Management, 27(13/14), 1504–1524.

Klink, R. R. (2001). Creating meaningful new brand names: A comparison of semantic and sound symbolism imbeds. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 9(2), 27–34.

Kohli, C., & LaBahn, D. W. (1997). Observations. creating effective brand names: A study of the naming process. Journal of Advertising Research, 37(1), 67–75.

Kotler, P. H. (1991). Marketing Management: Analysis, Planning, Implementation, and Control. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall Inc.

Kotler, P. H., & Gertner, D. (2002). Country as brand, product, and beyond: A place marketing and brand management perspective. Journal of Brand Management, 9(4), 249–261.

Lancaster, K. (1966). A new approach to consumer theory. Journal of Political Economy, 74, 132–157.

Larceneux, F. (2001). Critical opinion as a tool in the marketing of cultural products: The Experiential Label. International Journal of Arts Management, 3(3), 60–71.

Larceneux, F. (2003). Segmentation des signes de qualité: labels expérientiels et labels techniques. Décisions Marketing, 29, 35–47.

Leary, D. E. (1995). Naming and knowing: Giving forms to things unknown. Social Research, 62(2), 267–298.

Lorentz, P. (2007). Les ‘Maîtres’ anonymes: des noms provisoires fait pour durer? Perspective. La Revue de l’INHA, 1, 129–144.

Lupton, S. (2005). Shared quality uncertainty and the introduction of indeterminate goods. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 29(3), 399–421.

Mei, J., & Moses, M. (2002). Art as an investment and the underperformance of artworks. American Economic Review, 92(5), 1656–1668.

Miller, R. R., & Plott, C. R. (1985). Product quality signaling in experimental markets. Econometrica, 53(4), 837–872.

Mossetto, G. (1994). Cultural institutions and value formation of the art market: A rent-seeking approach. Public Choice, 81, 125–135.

Moulin, R. (1967). Le marché de la peinture en France. Paris: Éditions de minuit.

Muñiz, A. M., Jr., Norris, G., & Fine, A. (2014). Marketing artistic careers: Pablo Picasso as brand manager. European Journal of Marketing, 48(1/2), 68–88.

Nash, S. (2008). Northern Renaissance art. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nelson, P. (1970). Information and consumer behavior. Journal of Political Economy, 78(2), 311–329.

O’Reilly, D., & Kerrigan, F. (2010). Marketing the arts. In D. O’Reilly & F. Kerrigan (Eds.), Marketing the arts: A fresh approach (pp. 1–5). London & New York: Routledge.

Onofri, L. (2009). Old master paintings, export veto and price formation: An empirical study. European Journal of Law Economics, 28, 149–161.

Oosterlinck, K. (2017). Art as a wartime investment: Conspicuous consumption and discretion. Economic Journal, 607, 2665–2701.

Pesando, J. E. (1993). Art as an investment: The market for modern prints. American Economic Review, 83(5), 1075–1089.

Preece, C., & Kerrigan, F. (2015). Multi-stakeholder brand narratives: An analysis of the construction of artistic brands. Journal of Marketing Management, 31(11/12), 1207–1230.

Preece, C., Kerrigan, F., & O’Reilly, D. (2016). Framing the work: The composition of value in the visual arts. European Journal of Marketing, 50(7/8), 1377–1398.

Renneboog, L., & Spaenjers, C. (2013). Buying beauty: On prices and returns in the art market. Management Science, 59(1), 36–53.

Reynaud, N. (1978). Les Maîtres à noms de convention. Revue de l’art, 42, 41–52.

Robertson, K. (1989). Strategically desirable brand name characteristics. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 6, 61–71.

Rouet, P. (2001). Approach to the study of attic vases: Beazley and Pottier. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schroeder, J. E. (2005). The artist and the brand. European Journal of Marketing, 39(11–12), 1291–1305.

Schroeder, J. E., & Salzer-Mörling, M. (2006). Rethinking identity in brand management. In J. E. Schroeder & M. Salzer-Mörling (Eds.), Brand culture (pp. 118–135). London: Routledge.

Sjodin, H. (2007). Uh-oh, where is our brand headed?” Exploring the role of risk in brand change. Advances in Consumer Research, 34, 49–53.

Smallwood, D., & Conlisk, J. (1979). Product quality in markets where consumers are imperfectly informed. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 93(1), 1–23.

Spence, M. (1973). Job Market Signaling. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(3), 355–374.

Spence, M. (2002). Signaling in retrospect and the informational structure of markets. American Economic Review, 92(3), 434–459.

Stange, A. (1934-1961). Deutsche Malerei der Gotik. 11 vol., Berlin: Deutscher Kunstverlag.

Sterling, C. (1941). La peinture française. Les peintres du Moyen Âge. Paris: Pierre Tisné.

Syfer-d’Olne, P. (2006). The Flemish Primitives IV: Masters with Provisional Names. Brussels: Brepols.

Thieme, U., & Becker, F. (1950), Allgemeines Lexikon der Bildenden Künstler von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart. 37, Leipzig: Engelmann/Seemann.

Thomson, M. (2006). Human brands: investigating antecedents to consumers' strong attachments to celebrities. Journal of Marketing, 70(3), 104–119

Triplett, J. (2004), handbook on hedonic indexes and quality Adjustments in price indexes: Special application to information technology products. OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers, No. 2004/09, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/643587187107. Accessed 20 December 2017.

Turner, J. (1996). Grove dictionary of art: Masters, anonymous and monogrammists (Vol. 20). New York: McMillan Publishers.

Ursprung, H. W., & Wiermann, C. (2011). Reputation, price, and death: An empirical analysis of art price formation. Economic Inquiry, 49(3), 697–715.

Van den Brink, P. & Martens, M. P. J. (dir.) (2005), ExtravagAnt! Een kwarteeuw Antwerpse schilderkunst herontdekt/1500-1530, cat. expo. (Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen, 15 October – 31 December 2005/Bonnefantenmuseum Maastricht, 22 January—9 April 2006).

Velthuis, O. (2005). Talking prices. In Symbolic meanings of prices on the market for contemporary art. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Vermeylen, F. (2003). Paintings for the market: Commercialization of art in Antwerp’s golden age. Turnhout: Brepols.

Wankhade, L., & Dabade, B. (2010). Quality uncertainty due to information asymmetry. In L. Wankhade (Ed.), Quality uncertainty and perception (pp. 13–25). Berlin: Springer (Contributions to Management Science).

Wilenski, R. H. (1960). Flemish painters 1430–1830. London: Faber & Faber Ltd.

Wood, C. (1997). The great art boom, 1970–1997. Weybridge: Art Sales Index Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors are thankful for Diana Greenwald’s relevant comments, and highly useful remarks and recommendations suggested by two anonymous referees during the reviewing process.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Standard hedonic controls

With the exception of prices and dimensions, each characteristic is described by a variable that takes the value of one (if the characteristic is present) or zero otherwise.

-

Attribution qualifiers By (autograph), By and studio, Attributed to, Studio of, Circle of, School of, Follower of, After;

-

Technique Oil, Tempera, Other techniques;

-

Material Panel, Canvas, Other Materials;

-

Subject Allegory, Genre scenes, Landscape, Mythology, Portrait, Religious, Other scenes;

-

Dimensions height and width expressed in centimetres;

-

Date takes the value of one if the painting is dated, zero otherwise;

-

Signature takes the value of one if the painting is signed, zero otherwise;

-

Provenance takes the value of one if provenance information is provided, zero otherwise;

-

Exhibitions takes the value of one if the painting was previously exhibited, zero otherwise;

-

Literature takes the value of one if the painting is mentioned in the literature, zero otherwise;

-

Certificate takes the value of one if the painting is accompanied by a written certificate of authenticity, zero otherwise;

-

Salesrooms Artcurial, Bonhams, Christie’s London, Christie’s New York, Christie’s others, Dorotheum, Drouot, Koller, Lempertz, Phillips, Piasa, Sotheby’s London, Sotheby’s New York, Sotheby’s others, Tajan, Other salesrooms;

-

Year of sale from 1955 to 2015.

See Table 7.

Appendix 2. Regression results

See Table 8.

Appendix 3. Regression results of Model 1 (robustness tests)

Appendix 4. Regression results of Model 2 (robustness tests)

Appendix 5. Robustness test

See Table 14.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oosterlinck, K., Radermecker, AS. “The Master of …”: creating names for art history and the art market. J Cult Econ 43, 57–95 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-018-9329-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-018-9329-1