Abstract

Reputations of organizations and its individual members are valuable resources that help new organizations to get access to investment capital. Reputations, however, can have different dimensions. In this paper, we argue that an individual’s reputation along a particular dimension will have a positive effect on the behavior of investors when it is role congruent. In addition, we argue that also scoring favorably on the role-incongruent dimension at the same time—or, in other words, engaging in reputational category spanning—will weaken the positive effect of the role-congruent reputation. Our empirical setting is the film industry where we study the effect of the two main dimensions of reputation in cultural industries, artistic and commercial, of both directors and producers on the size of the investment by distributors. In this study, artistic reputation is based on professional critics’ reviews and commercial reputation on box office performance of the films in which individuals were involved in the past. We find that the commercial reputation of a film producer based on past box office performance has a positive effect on the size of the investment by film distributors. In addition, we find that directors who at the same time combine both a favorable commercial as well as an artistic reputation actually receive a lower investment from film distributors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Corporate reputations can derive from many different sources. Besides past performance in terms of perceived quality by consumers (Shapiro 1983; Podolny 1993), there are many other sources of reputation in the literature that include certification by third parties (Rao 1994), ratings (Durand et al. 2007), reviews (Basuroy et al. 2003; Eliashberg and Shugan 1997), awards (Anand and Watson 2004; Gemser et al. 2008) and even the mere volume of media attention (Pollock and Rindova 2003; Rindova et al. 2007). While many studies about corporate reputation focus on its effects on eventual market performance of firms (e.g., Fombrun and Shanley 1990; Roberts and Dowling 2002; Rindova et al. 2005), a related research stream focuses on the effects of corporate reputation on the behavior of resource providers, especially that of investors (Stuart et al. 1999; Certo 2003; Higgins and Gulati 2006).

However, a new organization in the process of being founded, and in search for investment capital, will suffer from a liability of newness (Freeman et al. 1983) since it does not have a corporate reputation based on its own past performance. Earlier studies, however, show that the reputations of important core members that are affiliated to an organization, such as CEOs (D’Aveni 1990; Higgins and Gulati 2003, 2006; Cohen and Dean 2005) or other board members (Certo 2003; Musteen et al. 2010), can also have an impact on the reputation of the firm as a whole. In addition, the composition (Deutsch and Ross 2003) of the board and the background (Beckman et al. 2007; Beckman and Burton 2008) of the top management team or individual entrepreneur (Hsu 2007) of a new firm has a significant effect on the behavior of investors.

Similar to corporate reputations, reputations of top management team members in new ventures in search of investment capital can derive from many sources. An important source is the performance of the organizations in which these individuals were involved in the past (Hsu 2007). In addition, since a reputation can have multiple facets or dimensions (Fombrun and Shanley 1990; Fombrun and Van Riel 1997; Jensen and Roy 2008), one might expect investors to differ with respect to the value they attach to the scores of these top management team members along these different dimensions of reputation. Investors may also be expected to pay attention to the ways in which the scores along different dimensions of the reputation are distributed among these founding members. In other words, building on Porac et al. (1995), one might expect investors to attach greater weight to dimensions of reputations that are particularly informative in relation to the role of the particular founder members, and which can, therefore, better serve as predictors of desired outcomes of an organization founded by members occupying these particular roles. Linking particular dimensions of reputation to the roles of the individuals to whom these reputations belong is important, since roles itself are also a means of getting access to resources (Baker and Faulkner 1991), such as investment capital.

Assuming that corporate reputations are constructed out of individual reputations that can be scored along different dimensions, it also becomes necessary to think about possible interactions. If one individual scores well along different dimensions of reputation; will this increase the reputational resources this individual brings to the organization? Or are there dimensions of reputation that are considered less compatible in particular contexts and, therefore, interact negatively? This study of the film industry will explicitly test this last possibility because it focuses on two dimensions of reputation—artistic and commercial—that precisely in cultural industries, such as the film industry, are seen to be not well compatible (Caves 2000) and are linked to competing logics (Glynn and Lounsbury 2005; Eikhof and Haunschild 2007).

Earlier studies (e.g., Delmestri et al. 2005; Holbrook and Addis 2008; Ferriani et al. 2009) already used these two dimensions in their analyses of the film industry. A recent study by Hadida (2010) showed that past commercial success—in terms of box office—has a positive effect on both the future budget and commercial performance of a film, while past artistic success of a film project team’s members—in terms of awards—is a good predictor of artistic performance. This paper will build on these earlier results and specifically focus on the effect of the individual reputations in relation to the specific roles of these individuals on the behavior of a particular group of investors, namely distributors offering minimum guarantees. Precisely by focusing on one group of investors who have similar motivations and have to make their decisions at a very early stage, long before any outcomes of the venture can be evaluated; we can test theoretical arguments about the impact of reputations based on past performance of the individuals involved in the new organization.

The first contribution of this paper is that we distinguish between different dimensions of reputations of new ventures’ founding members and study to what extent investor behavior is influenced by these dimensions of reputations being role congruent. We, therefore, study whether there is a positive relation between reputational scores along particular dimensions of particular founding members that occupy particular roles in the new venture, and the size of investments. Second, we will focus on the possible negative interaction effects between having a positive non-role-congruent reputation at the same time as a positive role-congruent reputation. Unfocused identities or category spanning may lead to more attention, but it is also risky since it could lead to lower appeal or negative evaluation (Zuckerman 1999; Zuckerman and Kim 2003; Zuckerman et al. 2003; Hsu 2006; Hsu et al. 2009). Unfocused reputations may be especially harmful if the different dimensions are incompatible. Again, this is especially relevant in the cultural industries where there is a possible tension between having both a favorable artistic as well as commercial reputation (Caves 2000).

Whereas previous studies focus on the risks of ex ante strategies of spanning categories such as a producer’s choice between making a multiple-genre as opposed to a single-genre film (Hsu 2006), or stretching identities by film actors and actresses trying to break away from being typecast for specific roles (Zuckerman et al. 2003), our study focuses on the effect of being positively evaluated ex post by different categories of evaluators along different dimensions of performance and how this subsequently affects investor behavior. In other words, we focus on the detrimental effects of having an unfocused reputation as a specific form of having an unfocused identity.

Although one would expect that past performance in more than one dimension at the same time would constitute a positive signal that reduces investment risk, this may also create uncertainty for investors with respect to the intentions of a founding member of a new ventures as to which goals he or she will pursue. In Hollywood, this is illustrated by director Michael Cimino who, after directing the both commercially and artistically highly successful film ‘the Deer Hunter’, nearly ruined the film studio United Artists with his huge flop ‘Heaven’s Gate’ (Bach 1999). In addition and possibly more important, it may also create uncertainty to investors as to which category of evaluators he or she will (try to) appeal to.

Reputations, and the issue of unfocused reputations, are especially relevant in the context of the cultural industries that are characterized by a high degree of uncertainty. In order to reduce risk, investors can regard the reputations of the founding members derived from their past performance as insurance. However, organizations in cultural industries also need to balance the tension between art and commerce (Caves 2000). A film can be a commercial success in terms of the number of tickets sold at the box office, but at the same time, it can be an artistic success in terms of favorable critics’ reviews (Gemser et al. 2007; Basuroy et al. 2003; Eliashberg and Shugan 1997). In this paper, we posit that investors face an investment risk when financing new ventures of which the core members have both a favorable commercial as well as a favorable artistic reputation at the same time.

The empirical setting of this paper is the film industry. The film industry is a highly uncertain and risky industry due to the high sunk costs and difficulty of predicting market demand. This is reflected in the ‘no one knows anything’ principle (Goldman 1984). Moreover, since in the film industry the strategic resources of an organization are almost all human resources, it seems reasonable to focus even more on the reputations of the key individuals involved. We limit ourselves to two dimensions of reputation: commercial and artistic, which are the basic dimensions along which performance is measured in cultural industries (Caves 2000). We also focus on two roles: the producer and the director, each of whom is specifically associated with one of these dimensions. The director is assumed to have the main responsibility for artistic quality, the producer for the commercial performance. The investors whose behavior we will study are the film distributors who have to decide on the size of the so-called minimum guarantee that they want to invest in a project when it is still in its pre-production stage.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. In the theory section, we review the literature on reputation and investment, and category spanning, on the basis of which a number of hypotheses will be proposed. This will be followed by a description of the research setting—the Dutch film industry—the data and the results. Discussion and conclusions will round off the paper.

2 Theory and hypotheses

2.1 Reputations and investment in new ventures

When the quality of a producers’ products are difficult to observe before an investment or purchase decision is made, actors can use the quality of past products as an indication of the quality of current or new products (Shapiro 1983). Reputation, in other words, refers to beliefs about the focal actor’s perceived qualities based on past performance. Reputation has economic importance because it helps decision-makers to make decisions in the absence of more complete information (Shapiro 1983; Fombrun and Shanley 1990; Podolny 1993). While products and individuals can have reputations, organizations can have corporate reputations (Fombrun 1996), which have an effect on the behavior of the organizational stakeholders, ranging from consumers to resource providers, such as investors. The effects of reputation on acquiring resources are seen most clearly in the case of new venture firms or entrepreneurs in search of financial resources.

New organizations, and especially organizations that are still in the process of being founded, suffer from a liability of newness (Freeman et al. 1983). While incumbents find their ability to obtain financial resources to be dependent on their reputation, new ventures are restricted in their access to financial resources due to a lack of reputation, (Milgrom and Roberts 1986; Fombrun and Shanley 1990; Stuart et al. 1999; Higgins and Gulati 2006; Kang 2008). However, new organizations do have members, and the composition of early membership can contribute to the organization’s corporate reputation. Musteen et al. (2010) show how the average tenure of outside directors has an impact on the corporate reputation of the firm. Pfeffer (1972) and Pfeffer and Salancik (1978) stress the extent to which the characteristics of individual directors can determine the firm’s ability to attract resources from external stakeholders. Busenitz et al. (2005) argue that the new venture founding team’s investment in their own venture functions as a signal to outside investors.

A crucial source of information for capital providers is the performance of the organizations in which these founding members of a new venture were involved in the past (Hsu 2007). Investors, in other words, will take the performance-based reputation of the core members of the new organization into account in their decision to provide startup capital. If founders of new organizations already set up other organizations in the past—so-called serial or habitual entrepreneurs (Westhead and Wright 1998)—potential investors will evaluate the new firm also on the basis of the prior performance of these earlier ventures. Likewise, prospective investors in project-based organizations (PBOs), organizations that dissolve once the project for which it was specifically set is finished (Jones 1996; DeFillippi and Arthur 1998), will evaluate the performance of the earlier PBOs in which the core members of the new PBO have been actively involved. In industries that are characterized by PBOs careers typically consist of a series of successive memberships in different PBOs.

2.2 Reputations, dimensions, and roles

A corporate reputation, however, can be scored along many dimensions. Organizations have reputations ‘…for something’ (Fisher and Reuber 2007: p. 57), for instance, for being well-managed, providing high product-quality, or excellence in customer service. Organizations can intentionally focus on building their scores along certain dimensions of reputation (Voss et al. 2000), for instance, to fit in administrative categories that make them eligible for receiving public or private grants and contracts, and, therefore, increase their chances of survival (DiMaggio and Powell 1983). Scoring high along a particular dimension of reputation functions as a form of categorization and can be expected to play a similar role in the decision-making processes of observers. With respect to firms, a tendency of focusing on a particular dimension of reputation will serve a similar purpose as using categories in a particular classification system, namely simplifying complex environments by focusing ‘on attributes that are particularly informative and predictive of organizational activities’ (Porac et al. 1995: p. 207), on the basis of which competitors are compared.

Because of their expected predictive value, investors in new ventures use reputational signals based on past performance of its individual founders as insurance for their current investments. Similar to corporate reputations, however, reputations of top management team members in new ventures in search of investment capital can derive from many sources. Earlier studies found a number of relations between the behavior of investors and the characteristics and personal background of an organization’s board (Deutsch and Ross 2003), differentiating between the CEO (D’Aveni 1990; Higgins and Gulati 2003, 2006; Cohen and Dean 2005) and other board members (Certo 2003; Musteen et al. 2010), the management team (Beckman et al. 2007; Beckman and Burton 2008) and the individual entrepreneur (Hsu 2007).

Although the individual reputations of board members or the entrepreneur turned out to be strong predictors of investor behavior, none of these studies looked at the value of particular dimensions of reputations in relation to individuals occupying particular roles and the concomitant responsibilities in the new organization. However, in their study of the film industry Baker and Faulkner (1991) found that individuals occupying particular roles are better able to attract resources such as investment capital (1991). They also show that if particular distributions of roles among the founding members of the organization were correlated with past success, new organizations with that particular distribution of roles were also more likely to attract investment capital. Yet Baker and Faulkner did not study the link between different dimensions of reputations in relation to individuals occupying particular roles and their concomitant responsibilities in these organizations. However, one might expect that it makes a difference to investors which dimensions of reputations are linked to which of the new venture’s top management team members and the role that they will perform. Especially with respect to new ventures and building on Porac et al., one might expect that investors categorize individual founding members of new ventures along the dimension of their reputation that is particularly informative, and which can serve as predictors of certain outcomes (Porac et al. 1995).

Where previous studies focus on either particular (combinations of) roles or (dimensions of) reputations as means of getting access to resources such as investment capital, we argue that it is important to link particular dimensions of reputation to the role of the individual to whom the reputation belongs. One might expect that there are different dimensions along which investors in a new venture score the performance of organizations and individuals, and that particular roles in the organization are strongly associated with particular dimensions of reputation. In a high-tech start-up, for example, the reputation for technological excellence will be linked more strongly to the individual reputation of the Chief Technical Officer, while the reputation for financial performance will be more strongly linked to the track record of the Chief Financial Officer. Alternatively, in the film industry, the most relevant dimensions of reputation are the artistic and the commercial ones that are predominantly linked to, respectively, the director and producer. Since corporate reputation along a particular dimension is expected to be closely linked to the individual reputation of the member of the organization whose role is most closely associated with that dimension, the arguments above suggest that the reputation scores of these individuals along these dimensions will have a strong impact on the behavior of investors toward the venture as a whole.

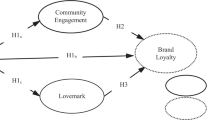

Hypothesis 1

There is a positive relation between the strength of role-congruent reputation of a founding member of a new organization and the size of investment in that organization.

2.3 The effects of having more than one good reputation

If an investor primarily determines the size of the investment based on the reputations of the involved individuals along the dimension that is role congruent (for the individual in a particular role), it would be interesting to study the effect of that individual also scoring favorably along another dimension of reputation that is not role congruent. Will favorable reputations always have a positive effect, even if they are not along dimensions that are linked to that specific role? Or does it detract from the extent to which the individual reputation contributes to the corporate reputation’s effect on behavior if the individual occupying that role also scores well along other dimensions at the same time?

There are two main arguments why there might be a negative interaction between the scores along the two dimensions. The first is that—in the particular environment in which the reputations are observed—the two dimensions are not considered to go well together or might even be considered incompatible, because the dimensions seem linked to different logics (Glynn and Lounsbury 2005). This would have the effect that individuals that score well along both dimensions of reputation will look less trustworthy to outside observers. The latter will, therefore, be less likely to base their decisions on this information. If one hears about an athlete who is great in weightlifting and in gymnastics, this sounds less trustworthy—because most people would assume that a body suitable to the one sport would be quite unsuitable for the other—than just hearing that she is a successful weightlifter.

It has often been noticed that in the cultural industries, there can be a strong tension between artistic and commercial objectives and performances (Caves 2000; Holbrook and Addis 2008) and the artistic and commercial logics to which they are linked (Glynn and Lounsbury 2005; Eikhof and Haunschild 2007). Although it is certainly not impossible—and there are notorious examples from each cultural industry—that a great artist also has a sound sense of business, this is not the expected state of affairs. Because of this, outside observers will be more hesitant to make decisions on the basis of a particular individual reputation if the individual also scores high along another dimension, while in the particular environment of the cultural industries performing along these two dimensions is considered to be likely to cause friction.

There could be a second argument why having a non-role-congruent reputation could affect the decisions of outside observers. A recent stream of literature studies the effects of belonging to more than one category—so-called category spanning (Zuckerman and Kim 2003; Zuckerman et al. 2003; Hsu and Hannan 2005; Hsu 2006; Hsu et al. 2009; Ruef and Patterson 2009). The main conclusion drawn from this literature is that, apart from producer-side effects of specialization (Hsu et al. 2009), having a clear identity increases visibility, makes it easer to get attention, and is helpful in gaining market entry. On the other hand, category spanning or complex identities will cause ambiguities, unclear expectations, and decreased legitimacy in the eyes of audiences, in turn resulting in lower evaluations and lower performance. A number of these studies were conducted in the empirical setting of the film industry with respect to the benefits and risks of actors and actresses being typecast (Zuckerman et al. 2003) and of producers making either single-genre or multi-genre films (Hsu 2006). Although the literature on category spanning and market identity focuses on product categories, and categories of organizational forms, we suggest that the underlying ideas may be just as well applicable to dimensions of reputation.

Since earlier research demonstrates the risk of unfocused identities or category spanning because it could lead to lower appeal or more negative evaluation (Zuckerman 1999; Zuckerman and Kim 2003; Zuckerman et al. 2003; Hsu 2006; Hsu et al. 2009), scoring favorably along multiple dimensions of reputation at the same time may also be risky. Thus, founding members of a new venture spanning reputational categories might be evaluated less positively, which will have a negative effect on the willingness of investors to provide start-up capital for the venture. Moreover, the negative effect due to the perceived lack of focus because of more than one strong reputation may be strengthened when there is a possible tension between different dimensions of reputation, such as the artistic and commercial dimensions (Caves 2000; Eikhof and Haunschild 2007). A professional with both a favorable artistic as well as a commercial reputation will have a less focused reputational identity than one who only scores well along the role-congruent dimension. Both arguments discussed here suggest a negative interaction effect. We, therefore, propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2

The positive relation between the strength of role-congruent reputation and investment in a new organization will be reduced by the strength of the non-congruent reputation of a founding member of that organization.

3 Methods

3.1 Research setting and data collection

The empirical setting of this study is the Dutch film industry. The film industry in general (Jones 1996; DeFillippi and Arthur 1998), and the Dutch film industry specific (Ebbers and Wijnberg 2009), is characterized by project-based organizations (PBO). We analyze the decisions of one group of investors: film distributors. Besides buying the distribution rights once the film is finished, distributors can also invest in a film project by providing a so-called minimum guarantee upfront. Film distributors are primarily interested in the commercial potential of the films in which they invest and, therefore, attempt to guess the taste of the consumers that will buy tickets at the box office (Eliashberg et al. 2008). Film distributors have the first share of the film rental revenues from box office sales until they recoup their investment—also called minimum guarantee—and the costs that they made in producing film prints for the film theaters and advertising costs (Blume 2004). The focus in our study is on two key roles in a film project: film producers and film directors, since these are the two founding members of a new film venture.

The two main dimensions of reputation in our study are derived from past artistic and commercial performance (Caves 2000). These two performance measures have also been distinguished in earlier studies of the film industry (Basuroy et al. 2003; Delmestri et al. 2005; Holbrook and Addis 2008; Ferriani et al. 2009) in which commercial performance is measured in terms of ticket sales at the box office (Sorenson and Waguespack 2006), while artistic performance is based on professional critics’ reviews (Eliashberg and Shugan 1997). The director is predominantly responsible for the artistic aspects of the film. The artistic reputation of a director can attract other high quality professionals with artistic roles such as cinematographers and actors (Delmestri et al. 2005) and be a predictor of a new film’s artistic success. The producer’s reputation is related to his track record of successfully coordinating and assembling resources and—together with the distributor—delivering commercially success films (Sorenson and Waguespack 2006).

The investment data we use in this study are collected from the archives of the Dutch Film Fund (DFF). The DFF provides production subsidies to Dutch films and keeps a record with financial data of most Dutch films. This database includes, among other things, the names of the director and producer and the size of the investment or minimum guarantee provided by which distributor. For this study, we used data of 246 films Dutch films released in Dutch film theaters between 1992 and 2008. Dutch films are operationalized as films of which the producer and the director either have the Dutch nationality or attended the Dutch Film Academy. The Dutch Film Academy is the most prominent film school in the Netherlands. The films released between 1992 and 1998 were used for constructing the reputation variables in terms of past commercial and artistic performance of the directors and producers that are involved in the new film venture. We used these two dimensions of reputation to explain investment decisions for all the film that where released in film theaters between 1998 and 2008.

3.2 Dependent variable

The dependent variable distributor investment is the absolute size of the investment of a film distributor in Euros (n = 141) in a particular film project. The investment of distributors is driven by their evaluation of a film project’s commercial potential or expected future earnings in the market. Distributors invest in film productions by providing so-called minimum guarantees (MG) in exchange for the distribution rights. The MG is an upfront compensation for expected future earnings that producers can invest in the production of a film in exchange for the distribution rights. Distributors are the first to recoup their minimum guarantee from the commercial exploitation of the film, before the DFF earns back the subsidies that they provided and before they start paying royalties to the producer and key creative personnel.

3.3 Independent variables

In order to measure the effect of reputations on the size of the investments, we operationalized reputation as the average performance of the last three films of the producer and director before the investment decision was made with respect to the focal film. The film data that we collected are categorized by their release year. On average, there is a 2-year time lag between the capital investment decision and the eventual release in the theaters. Therefore, we used the last three films prior to the release date of the focal film minus 2 years to construct the reputation variables. Producers and directors who aspire to make their very first film do not have a proven track record that is visible in our data. However, this does not necessarily mean that they are novices with no relevant reputation. Directors and producers who make their first film may have gained experience in neighboring industries such as television, commercials, or theater before they make the switch to film (Storper 1989). We, therefore, coded new entrants in the film industry as having an average reputation. At the same time, we added control dummy variables for producers and directors who make their debut (see below).

3.3.1 Commercial reputation

Box office success is an often used construct for measuring commercial performance of films (see, e.g., Sorenson and Waguespack 2006; Delmestri et al. 2005). We used the cumulative box office revenues over all consecutive years of a film’s first run in the theaters. The commercial reputation of producers and directors is derived from box office ticket sales in film theaters and measured as the average cumulative box office performance of the last 3 films prior to the expected investment decision—2 years before the eventual release year. Box office data of films released in the period 1992–2008 was obtained through the Dutch Association of Film Distributors.Footnote 1

3.3.2 Artistic reputation

The artistic reputation of producers and directors is derived from the average film critics’ reviews of the last 3 films prior to the investment decision of the focal film. Critics’ reviews are measured in the number of stars on a scale from 0 to 5. The more stars, the more positive the critic’s review. We used the average number of stars in the ratings of film reviews in the four largest Dutch national newspapers—Algemeen Dagblad, Volkskrant, NRC Handelsblad, and Telegraaf—to rate the artistic performance of individual films, and in turn, artistic reputations of producers and directors. The review data in these newspapers are collected by and published in the Filmkrant, a magazine dedicated to film.

3.4 Control variables

We included a number of control variables that are likely to affect our model. First, the control variable budget is included since large budget films have a higher production value. A big budget allows producers to include, for example, more actors, special effects, stunts, exotic locations, and extras, which in turn, make it relatively easier for the distributor to market and sell the film. The budget variable includes government subsidies and investments from public television broadcasters. Film distributors, however, have the first share of the film rental revenues from box office sales until they recoup their investment (MG) and the costs that they made in producing film prints and advertising costs (Blume 2004).

Second, we constructed two debut dummy variables to control for the effects of new entry of producers and directors without prior experience in the film industry and as such suffer from a liability of newness (Freeman et al. 1983).

Third, we included a control for original script. Film scripts that are based on books or theater plays that have proven their commercial value are expected to increase the chance of success of the subsequent film (Ferriani et al. 2009).

Fourth, we included controls for prior collaboration director and prior collaboration producer since new venture investors in general (Shane and Cable 2002), and film distributors more specific, tend to favor and allocate more resources to new ventures of prior collaboration partners (Sorenson and Waguespack 2006).

Finally, we included three genres dummies for comedy, action, and family films. Especially comedies are known to be difficult to export, and therefore, one might expect that distributors have a preference for investing in locally produced comedies (Friedman 2004). The comedy dummy includes (romantic) comedies and romantic films. The action dummy includes thriller, horror, crime, and adventure. The family dummy includes children’s films. The baseline group is drama and includes historic dramas.

3.5 Analytical approach

We performed a robust hierarchical regression analysis for estimating the standard errors using Huber-White sandwich estimators that reduces the influence of outliers or extreme values in the data (White 1980). As a rule of thumb, 20 percent of the films earn 80 percent of the revenues (DeVany and Walls 1996). This could also mean that individual commercial reputations that are derived from the commercial success of an individual’s last three films might turn out to be skewed. We performed a hierarchical analysis that allows us to compare increasingly complex models. This is especially relevant when one wants to compare models with main effects, with subsequent models that include interaction effects. Possible interaction effects between different dimensions of reputations—commercial or artistic—of producers and directors are only meaningful if adding them to the model explains significantly more variance (Jaccard and Turrisi 2003). Before we included the interaction terms, we mean centered the independent variables (Cohen et al. 2003). Before we performed the regressions, we assessed whether our data suffer from multicollinearity problems. Multicollinearity is not a problem since we found no significant variance inflation factor (VIF) values (Mean VIF = 1.32 and largest VIF = 1.57).

4 Results

Table 1 provides the descriptive statistics and correlations for all the variables. Table 2 shows the results of the robust hierarchical regression analysis. In the first step, we estimated a control model including the variables budget, producer debut, director debut, original script, prior tie between distributor and director, prior tie between distributor and producer, and the genre dummies comedy, action, and family. Model 1 shows that the variables, budget and comedy, have a positive and significant effect on the size of the distributor investment in a new film (Model 1: R 2 = .53, p < 0,001). There is also a weakly significant positive effect for prior tie distributor and director or when a specific director and distributor have collaborated before in the past. However, contrary to earlier studies on the film industry, prior ties between distributors and producers, do not lead to the former investing more resources in the latter’s new film (Sorenson and Waguespack 2006) in terms of a larger MG.

The difference between what we find and the earlier findings by Sorenson and Waguespack (2006) might be explained by the relatively small size of the Dutch film industry, which makes it more likely that distributors have met and had some contacts with most individual producers and directors, even if they have not formally collaborated. In turn, this will decrease the effect of having prior ties resulting from the familiarity one has with individuals one has collaborated with before. Producers or directors who make their debut in the film industry do not receive a significantly different investment. This is an indication that our practice of coding new entrants with an average reputation is not likely to have affected the analysis. Also the fact that a film has an original script as opposed to one based on a book or theater play does not have a significant effect on the size of the distributor investment.

In the second step, we included the commercial and artistic reputations of producers and directors. This model allows us to test hypothesis 1. Including the four reputation variables did not significantly increase the explained variance of the model (Model 2: ΔR 2 = .02, p = 0.15). Based on earlier studies, one would expect to find a positive effect of commercial reputation on the size of the distributor investment, since the latter can use information about past box office performance to reduce the risk of commercial failure of the new venture. We only found a weakly significant effect for the commercial reputation of the producer (β = .15, p < 0.1), not the director. This finding partly confirms our hypothesis 1 stating that investment will increase when the particular dimension of reputation is role congruent

In the third step, we included interaction terms to test hypothesis 2. This hypothesis is concerned with the effects of reputation category spanning, or the consequences of founding members of new ventures having a fuzzy reputation, on the amount of investment one can attract for a new venture. The added interaction terms between the different dimensions of reputation of both producers and directors in model 3 explain significantly more variance (Model 3: ΔR 2 = .04, p < 0.001). We found partial support for hypothesis 3 that stipulates a negative effect of category spanning of different reputation dimensions at the individual role level and the size of the investors’ investment. With regard to the individual coefficients, reputation category spanning by directors (β = −.14, p < 0.05) has a negative and significant effect on the size of the MG. Reputational category spanning is not significant for the producer role.

Figure 1 shows that although there are no individual effects of commercial and artistic reputation of directors on the size of the distributor MG—see also model 2—the interaction between the two dimensions is significant (β = −.14, p < 0.05). Directors involved in new ventures that simultaneously have a high artistic and a high commercial reputation, receive a lower investment for their new film project. Figure 1 visualizes that a fuzzy reputation, in other words, has a negative effect on the ability of core members of new organizations to attract start-up capital.

We performed several robustness checks and alternative models. First, we performed a robustness check by performing an OLS and a regular hierarchical regression instead of a robust regression using White-Huber sandwich estimators. The findings were consistent with our baseline model. We reported the robust hierarchical regression model as our main model because the film industry—being a creative industry—is characterized by a large hit-to-flop ratio and robust regression allows one to downplay the influence of this small number of hits on the overall results.

Second, we performed a robustness check in which we coded the reputations of new entrants lower than the average used in the main model. Since we did not know whether or not new entrants that search for investment capital for their first film have a good or bad reputation in neighboring industries such as television or theater, we performed a similar regression analysis with the only difference that we coded new entrants as having a lower reputation. Instead of coding new entrants as having an average reputation, we coded new entrants’ reputations between 0 and the average reputation of those actors in the sample with a similar role who did make earlier films. The results of the regressions after this recoding were also consistent with our earlier findings. The effect sizes are even somewhat larger.

Third, we ran a regression in which we deleted all films with new entrants and only producers and directors that made a film before the one for which we estimate the size of the minimum guarantee (n = 57). We found that the commercial reputation of the producer—although the sign remains positive—becomes insignificant. The interaction effect between the commercial and artistic reputation of the director becomes insignificant although the sign is still negative. Although we did not find a significant interaction effect in our original model—which included new entrants—we do find a strong, negative, and significant interaction effect between the commercial and artistic reputation of the producer (β = .24, p < 0.05). Taking into account the low statistical power of this small sample regression, finding a significant interaction effect in this small sample size provides strong support for our hypothesis with respect to the negative effect of having more than one good reputation.

Fourth, besides interactions between reputations within roles, we also estimated a model that included all other interactions between roles. This allowed us to study how particular combinations of reputations at the team level—producer and director—could explain the amount of investment received. We, therefore, include four additional interactions: commercial reputation director × commercial reputation producer, artistic reputation director × artistic reputation producer, artistic reputation director × commercial reputation producer, and commercial reputation director × artistic reputation producer. However, none of these interactions was significant.

We also estimated a number of alternative models not presented in this paper but available on request. First, instead of using debut dummies for producers and directors that are new entrants in the industry, we included alternative control variables that measured experience in terms of number of years that producers and directors have been active in the film industry. This slightly increased the significance level of the commercial reputation of the producer (p < 0.05). Second, we added interactions between these alternative industry experience variables and the reputation variables to check whether certain dimensions of reputations are more important depending on career age. These interactions were not significant. Third, we included dummy variables for both film producers and directors who attended the most prestigious film school in the Netherlands, the Dutch Film and Television Academy. Both variables were not significant.

5 Discussion and conclusion

In this study, we investigated the effect of reputations of founding members of a new organization on the amount of investment capital that the new venture receives from outside investors. Organizations that are new or in the process of being founded encounter difficulties because they lack a performance track record or reputation for delivering quality products (Freeman et al. 1983). While incumbents find their abilities to obtain financial resources to be dependent on their reputation (Milgrom and Roberts 1986; Fombrun and Shanley 1990; Stuart et al. 1999; Higgins and Gulati 2006; Kang 2008), new organizations, especially in the start-up phase, are restricted in their access to financial resources due to this lack of reputation. Earlier studies, however, show that the reputations of core members of an organization—not necessarily new—such as top management teams, have an impact on the reputation of the organization as a whole (Higgins and Gulati 2006; Cohen and Dean 2005).

This study has build on these results to better understand how precisely the individual reputations of core members of the organization affects the new organization’s ability to attract financial resources. Besides clarifying this general point, the core contributions of the study results from fully taking into account multiple dimensions of reputation, multiple roles in the organization that are more or less linked with particular dimensions of reputation, and finally, the possibility that an individual’s reputations along different dimensions can interact.

First, we filled a gap in current research by focusing on the value of scores along different dimensions of reputations of core members of new ventures. We specifically studied the effect of these reputations in attracting investment capital to new project-based organizations. A new PBO per definition has no prior history and can be regarded as an extreme case of a new organization that has to derive its corporate reputation from the reputations of its key members. We found partial confirmation that the behavior of investors is affected by an individual reputation along the dimension that best suits their own values and goals, while reputation along the other dimension—however, much appreciated by stakeholders in general—has no significant effect.

In our empirical setting of the film industry, we found evidence that investor behavior in terms of providing start-up capital to new ventures is mainly affected by the commercial reputation of its founding members. This is generally in accordance with the findings of an earlier study that the commercial track records of the core members of the team are a predictor of the overall budget of the film production (Hadida 2010). Our data clearly indicate that reputational scores along the commercial dimension significantly predicted investments by distributors, while scores along the artistic dimension did not.

Second, by distinguishing between different roles within the organization that can be linked to particular dimensions of reputation, we found that the way in which reputations along particular dimensions is distributed among the occupants of these roles has a significant effect on the decision making behaviour. Reputational assets are not good in themselves, but they are good if they originate from individuals performing particular roles. We found that an investor attaches the most value to the reputation dimension that is not just aligned with the investor’s own values and goals, but that originates from the individual occupying the role that is most closely aligned with that dimension. This suggests that particular dimensions of reputation are only valuable if they are role congruent. Scores along the other dimension had no significant effect on the willingness of investors to provide start-up capital.

In our empirical case of the film industry, we found that the commercial reputation of the individual occupying the role of producer has a strong effect on the size of the distributor’s investment. Neither the commercial nor the artistic reputation of the director was found to have a significant effect. A possible explanation for this finding could be that distributors find it more difficult to evaluate directors directly and to some extent rely on the judgment of the producer the commercial reputation of whom they value highly. If that would be the case, the outside investor would not directly evaluate the whole founding team.

Third, we found that scoring highly along both dimensions (by the individual members of the management team) may have adverse effects on the willingness of investors to provide capital to new ventures. More sometimes is less. Adding a good reputation along another dimension to a good reputation along the favored dimension decreased the effect of the latter. We found that directors who at the same time score well along both the commercial and the artistic dimension of reputation are less attractive to investors.

This could be explained by the composite signal becoming less trustworthy because of the assumption, among the outside observers, of the tension between artistic and commercial talents and attitudes or of the signal becoming fuzzier and less convincing because of the category-spanning effect (Zuckerman et al. 2003; Hsu 2006; Hsu et al. 2009). These directors create uncertainty among investors as to which audiences will be attracted to the new film venture. Besides uncertainty with respect to the film’s appeal to consumers and evaluators such as film critics, it also creates uncertainty about the reputations of the other film professionals—in the sense of resource providers—that will be attracted to the PBO. Directors with both a high artistic and commercial reputation may attract other PBO members that may have either high artistic or commercial reputations or both. This, in turn, increases the uncertainty as to which type of audience the film will appeal to when it is completed.

It is clear that organizations, and especially new ventures, should take into consideration not just the aims and values of all relevant audiences, but also the individual reputations of core actors occupying particular roles in the organization and the ways in which these individual reputations and their perceived value can combine in the perception of a particular audience.

Our study has a number of limitations that also point the way toward further research. First, as is often the case in research on new ventures, there is a bias toward those firms that made it from the original idea toward realization. We did not have data of film projects that failed to pass the first phase in the competitive process of receiving investment capital. We focused exclusively on the relationship between reputation and investment size for films that made it through the investment phase. Future studies that include data about projects that were rejected by all investors would provide a valuable extension of our understanding of investor behavior. However, trustworthy data of that kind are hard to find in most studies about new ventures.

Second, our database of films derives from the Dutch Film Fund (DFF). The role and mission of the DFF is to cultivate the climate for Dutch film culture and to stimulate film production in the Netherlands with an emphasis on diversity and quality. This means that we only have data about films that received a certain amount of government subsidies through the Dutch Film Fund. Based on our last year of films in the database (2008), however, 25% of the films are made without support from the Dutch Film Fund. This category consists of a wide diversity of films. For example, it also includes a number of films that were made for television and as such did not receive a minimum guarantee from distributors.

Third, we restricted ourselves to the most important reputational signals that were also used in previous studies, instead of taking all possible reputational signals into account. For instance, we ignored the success of Dutch films abroad, especially in the sense of selection for international film festivals, and being nominated for or winning awards at these festivals.

Fourth, we focused on the effect of reputational signals and ignored other quality signals that may be known to the providers of financial resources during the investment decision-making process. The specific characteristics of the script and the scriptwriter, for example, may also be possible determinant of receiving investment capital (Eliashberg et al. 2007).

Another suggested predictor of investment decisions in the film industry is the involvement of star actors in the project, or the credible suggestion of such star involvement (Elberse 2007; Hadida 2010). We did not have data about the involvement of stars at the moment when the investment decision was made. However, besides evidence from the US that stars are no guarantee for commercial success (DeVany and Walls 1999), stars are also less important in the European than in the American film industry (Delmestri et al. 2005).

Finally, we only focused on two dimensions of reputation and two roles inside the organization. This limitation is realistic for the particular environment we studied, since, as we discussed above, film projects in the Netherlands are proposed to investors by the producer and director of the future project. Also, in a cultural industry such as film, the tension between art and commerce is a well-known phenomenon, almost a cliché. However, the general arguments proposed in this paper seem relevant for studying the behavior of all possible audiences with respect to all kinds of organizations the corporate reputations of which can be considered to score along multiple dimensions that are linked to the individual reputations of some of its members. Replication of this study in other cultural industries, as well as in other industries, in which different dimensions of reputation can be distinguished, could further test the generalizability of our study.

The subject of our empirical study was particularly well suited for establishing the effects of individual performance-based reputations as constituents of corporate reputation, precisely because in the case of film projects in the financing stage, the project organization itself has no reputation apart from these individual reputations. Further studies concerning organizations that do have reputation-relevant history would allow to explore the interactions between the individual reputations and the past performance of the organization on the decisions made by relevant audiences—investors, but also, for instance, customers and employees—that in the end result in future performance differentials.

Notes

Nederlandse Vereniging van Filmdistributeurs (NVF).

References

Anand, N., & Watson, M. R. (2004). Tournament rituals in the evolution of fields: The case of the Grammy awards. Academy of Management Journal, 47(1), 59–80.

Bach, S. (1999). Final cut: Art, money, and ego in the making of heaven’s gate, the film that sank united artists. New York, NY: Newmarket Press.

Baker, W. E., & Faulkner, R. R. (1991). Role as a resource in the Hollywood film industry. American Journal of Sociology, 97(2), 279–309.

Basuroy, S., Chatterjee, S., & Ravid, S. A. (2003). How critical are critical reviews? The box office effects of film critics, star power, and budgets. Journal of Marketing, 67(4), 103–117.

Beckman, C. M., & Burton, M. D. (2008). Founding the future: Path dependence in the evolution of top management teams from founding to IPO. Organization Science, 19(1), 3–24.

Beckman, C. M., Burton, M. D., & O’Reilly, C. (2007). Early teams: The impact of team demography on VC financing and going public. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(2), 147–173.

Blume, S. E. (2004). The revenue streams: An overview. In J. E. Squire (Ed.), The movie business book (pp. 332–359). New York: Fireside.

Busenitz, L. W., Fiet, J. O., & Moesel, D. D. (2005). Signaling in venture capitalist–new venture team funding decisions: Does it indicate long-term venture outcomes? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(1), 1–12.

Caves, R. E. (2000). Creative industries: Contracts between art and commerce. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Certo, S. T. (2003). Influencing the initial public offering investors with prestige: Signaling with board structures. Academy of Management Review, 28(3), 432–446.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaump.

Cohen, B. D., & Dean, T. J. (2005). Information asymmetry and shareholder evaluation of IPOs: Top management team legitimacy as a capital market signal. Strategic Management Journal, 26(7), 683–690.

D’Aveni, R. A. (1990). Top management prestige and organizational bankruptcy. Organization Science, 1(2), 121–142.

DeFillippi, R. J., & Arthur, M. B. (1998). Paradox in project-based enterprise: The case of film making. California Management Review, 40(2), 1–15.

Delmestri, G., Montanari, F., & Usai, A. (2005). Reputation and strength of ties in predicting commercial success and artistic merit of independents in the Italian feature film industry. Journal of Management Studies, 42(5), 975–1002.

Deutsch, Y., & Ross, T. W. (2003). You are known by the directors you keep: Reputable directors as a signaling mechanism for young firms. Management Science, 49(8), 1003–1017.

DeVany, A., & Walls, D. (1996). Bose-Einstein dynamics and adaptive contracting in the motion picture industry. Economic Journal, 106, 1493–1514.

DeVany, A., & Walls, W. D. (1999). Uncertainty in the movie industry: Does star power reduce the terror of the box office? Journal of Cultural Economics, 23, 285–318.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160.

Durand, R., Rao, H., & Monin, P. (2007). Code and conduct in French cuisine: Impact of code changes on external evaluations. Strategic Management Journal, 28(5), 455–472.

Ebbers, J. J., & Wijnberg, N. M. (2009). Latent organizations in the film industry: Contracts, rewards and resources. Human Relations, 62(7), 987–1009.

Eikhof, D. R., & Haunschild, A. (2007). For art’s sake! Artistic and economic logics in creative production. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 28, 523–538.

Elberse, A. (2007). The power of stars: Do star actors drive the success of movies? Journal of Marketing, 71(4), 102–120.

Eliashberg, J., Hui, K., & Zhang, Z. J. (2007). From story line to box office: A new approach for green-lighting movie scripts. Management Science, 53(6), 881–893.

Eliashberg, J., & Shugan, S. M. (1997). Film critics: Influencers or predictors? Journal of Marketing, 61(2), 68–78.

Eliashberg, J., Weinberg, C., & Hui, S. K. (2008). Decision models for the movie industry. In B. Wierenga (Ed.), Handbook of marketing decision models (pp. 437–468). New York: Springer.

Ferriani, S., Cattani, G., & Baden-Fuller, C. (2009). The relational antecedents of project- entrepreneurship: Network centrality, team composition and project performance. Research Policy, 38(10), 1545–1558.

Fisher, E., & Reuber, R. (2007). The good, the bad, and the unfamiliar: The challenges of reputation formation facing new firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(1), 53–75.

Fombrun, C. (1996). Reputation: Realizing value from the corporate image. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Fombrun, C., & Shanley, M. (1990). What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy of Management Journal, 33(2), 233–258.

Fombrun, C. J., & Van Riel, C. B. M. (1997). The reputational landscape. Corporate Reputation Review, 1, 5–13.

Freeman, J., Carroll, G. R., & Hannan, M. T. (1983). The liability of newness: Age dependence in organizational death rates. American Sociological Review, 48(5), 692–710.

Friedman, R. G. (2004). Motion picture marketing. In J. E. Squire (Ed.), The movie business book (pp. 282–299). New York: Fireside.

Gemser, G., Leenders, M. A. A. M., & Wijnberg, N. M. (2008). Why some awards are more effective signals of quality than others: A study of movie awards. Journal of Management, 34(1), 25–54.

Gemser, G., Van Oostrum, M., & Leenders, M. A. A. M. (2007). The impact of film reviews on the box office performance of art house versus mainstream motion pictures. Journal of Cultural Economics, 31, 43–63.

Glynn, M. A., & Lounsbury, M. (2005). From the critics’ corner: Logic blending, discursive change and authenticity in a cultural production system. Journal of Management Studies, 42(5), 1031–1055.

Hadida, A. (2010). Commercial success and artistic recognition of motion picture projects. Journal of Cultural Economics, 34, 45–80.

Higgins, M. C., & Gulati, R. (2003). Getting off to a good start: The effects of upper echelon affiliations on underwriter prestige. Organization Science, 14(3), 244–263.

Higgins, M. C., & Gulati, R. (2006). Stacking the deck: The effects of top management backgrounds on investor decisions. Strategic Management Journal, 27(1), 1–25.

Holbrook, M. B., & Addis, M. (2008). Art versus commerce in the movie industry: A two-path model of motion-picture success. Journal of Cultural Economics, 32(2), 87–107.

Hsu, G. (2006). Jacks of all trades and masters of none: Audiences’ reactions to spanning genres in feature film production. Administrative Science Quarterly, 51(3), 420–450.

Hsu, D. H. (2007). Experienced entrepreneurial founders, organizational capital, and venture capital funding. Research Policy, 36(5), 722–741.

Hsu, G., & Hannan, M. T. (2005). Identities, genres, and organizational forms. Organization Science, 16(5), 474–490.

Hsu, G., Hannan, M. T., & Koçak, Ö. (2009). Multiple category memberships in markets: An integrative theory and two empirical tests. American Sociological Review, 74(1), 150–169.

Jaccard, J., & Turrisi, R. (2003). Interaction effects in multiple regression (2nd ed.). Sage: Thousand Oaks.

Jensen, M., & Roy, A. (2008). Staging exchange partner choices: When do status and reputation matter? Academy of Management Journal, 51, 495–516.

Jones, C. (1996). Careers in project networks: The case of the film industry. In M. B. Arthur & D. M. Rousseau (Eds.), The boundaryless career (pp. 58–75). New York: Oxford University Press.

Kang, E. (2008). Director interlocks and spillover effects or reputational penalties from financial reporting fraud. Academy of Management Journal, 51(3), 537–555.

Milgrom, P., & Roberts, J. (1986). Price and advertising signals of product quality. Journal of Political Economy, 94(4), 796–821.

Musteen, M., Datta, D. K., & Kemmerer, B. (2010). Corporate reputation: Do board characteristics matter? British Journal of Management, 21(2), 98–510.

Pfeffer, J. (1972). Size and composition of corporate boards of directors: The organization and its environment. Administrative Science Quarterly, 17(2), 218–229.

Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. R. (1978). The external control of organizations: A resource dependence perspective. New York: Harper and Row.

Podolny, J. M. (1993). A status-based model of market competition. American Journal of Sociology, 98(4), 829–872.

Pollock, T. G., & Rindova, V. R. (2003). Media legitimation effects in the market for initial public offerings. Academy of Management Journal, 46(5), 631–642.

Porac, J. F., Howard, T., Wilson, F., Paton, D., & Kanfer, A. (1995). Rivalry and the industry model of Scottish knitwear producers. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40(2), 203–227.

Rao, H. (1994). The social construction of reputation: Certification contests, legitimation, and the survival of organizations in the American automobile industry: 1895–1912. Strategic Management Journal, 15, 29–44.

Rindova, V. P., Petkova, A. P., & Kotha, S. (2007). Standing out: How new firms in emerging markets build reputation. Strategic Organization, 5(1), 31–70.

Rindova, V. P., Williamson, I. O., Petkova, A. P., & Sever, J. M. (2005). Being good or being known: An empirical examination of the dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of organizational reputation. Academy of Management Journal, 48(6), 1033–1049.

Roberts, P. W., & Dowling, G. R. (2002). Corporate reputation and sustained financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 23(12), 1077–1093.

Ruef, M., & Patterson, K. (2009). Credit and classification: The impact of industry boundaries in nineteenth-century America. Administrative Science Quarterly, 54, 486–520.

Shane, S., & Cable, D. (2002). Network ties, reputation, and the financing of new ventures. Management Science, 48(3), 364–381.

Shapiro, C. (1983). Premiums for high quality products as returns to reputations. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 98(4), 659–680.

Sorenson, O., & Waguespack, D. (2006). Social structure and exchange: Self- confirming dynamics in Hollywood. Administrative Science Quarterly, 51(4), 560–589.

Storper, M. (1989). The transition to flexible specialisation in the US film industry: External economies, the division of labour, and the crossing of industrial divides. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 13(2), 273–305.

Stuart, T. E., Hoang, H., & Hybels, R. C. (1999). Interorganizational endorsements and the performance of entrepreneurial ventures. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 315–349.

Voss, G. B., Cable, D. M., & Voss, Z. G. (2000). Linking organizational values to relationships with external constituents: A study of nonprofit professional theatres. Organization Science, 11(3), 330–347.

Westhead, P., & Wright, M. (1998). Novice, serial, and portfolio founders: Are they different? Journal of Business Venturing, 13(3), 173–204.

White, H. (1980). A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica, 48, 817–830.

Zuckerman, E. W. (1999). The categorical imperative: Securities analysts and the illegitimacy discount. American Journal of Sociology, 104(5), 1398–1438.

Zuckerman, E. W., & Kim, T. Y. (2003). The critical trade-off: Identity assignment and box-office success in the feature film industry. Industrial and Corporate Change, 12(1), 27–67.

Zuckerman, E. W., Kim, T. Y., Ukanwa, K., & Von Rittman, J. J. (2003). Robust identities or non-entities? Typecasting in the feature film labor market. American Journal of Sociology, 108(5), 1018–1074.

Acknowledgments

This research has been made possible with the help of the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research–Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijke Onderzoek (NWO)–under grant number 400-07-160. We also want to thank the VandenEnde Foundation for their support in creating the Chair of Cultural Entrepreneurship and Management at the Amsterdam Business School, the Dutch Film Fund and the Dutch Association of Film Distributors for providing access to data, Stephen Mezias for his helpful suggestions, and the editor and anonymous reviewers of the Journal of Cultural Economics for their valuable feedback.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ebbers, J.J., Wijnberg, N.M. The effects of having more than one good reputation on distributor investments in the film industry. J Cult Econ 36, 227–248 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-012-9160-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-012-9160-z