Abstract

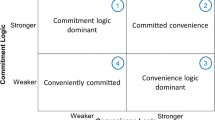

We present an empirical analysis of product differentiation using a new panel data set on film-programming choice in a major U.S. metropolitan motion-pictures exhibition market. Using these data, we compute two measures of product similarity, which allow us to investigate the determinants of strategic product differentiation in a multi-characteristics space. Our evidence is consistent with the idea that the degree of product differentiation between theatre pairs reflects a balance between strategic concerns and contractual constraints. Similarity in one dimension is offset by differentiation in others. Our results further suggest that the degree of product differentiation is negatively related to market size. Finally, we find that ownership matters: theatres under common ownership make more similar programming choices than theatres with different owners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Tirole refers to a similar tension between differentiation to soften price competition and agglomeration to “be where the demand is” (1988, p. 286).

Synergy Retail Group, a retail real estate market research services firm, collected the baseline data set used in our analysis. Synergy determined each theatre’s type based on theatre advertisements and by contacting theatres directly, as needed. All theatres in the Boston and surrounding area were classified into three types: first-run (excluding art house theatres), art house, and second-run or discount. This article focuses on only first-run theatres. We exclude arthouse and second-run theatres on the assumption that such theatres serve markets with consumer preferences for different attributes (e.g., film type; currency of film) from the first-run theatre market. We limit the geographic scope of the market to an area within or near the radial market defined by the I-95 loop around Boston.

One might expect theatres to further differentiate their offerings from their competitors’ by exhibiting films at non-overlapping times. On this margin, a typical exhibition format includes showing a film in the early afternoon, the late afternoon, the early evening, and the later evening. Deviations from this format are more common within a given theatre, when a film is shown on more than one screen, than across theatres. An interesting question for further study is why theatres do not generally deviate from a common structure of film showings.

Theatres owned by National Amusements include: Cleveland Circle Cinemas (Brookline); Showcase Cinemas of Dedham; Showcase Cinemas of Randolph; Showcase Cinemas of Revere; and Showcase Cinemas of Woburn. Theatres owned by General Cinema include: Braintree 10; Burlington 10; Chestnut Hill Cinema 5; and Fenway 13 (Boston). Theatres owned by Loews Cineplex Entertainment include: Assembly Square (Somerville); Copley Place (Boston); Fresh Pond 10 (Cambridge); and Liberty Tree Mall (Danvers). In addition, National Amusements owned Quincy Cinemas; this theatre is not included in our sample due to data limitations on showtimes, however, we do account for its influence on the market in our market-boundary measures described below.

General Cinema Corporation filed for Chap. 11 reorganization on October 11, 2000; AMC Entertainment won approval to acquire General Cinema’s assets in March 2002. The GCC theatres in the Boston market operated continuously throughout our period of study, and the quality and features of the theatres were similar to competing first-run theatres in the Boston market. See “Court Approves GC Cos. Sale to AMC,” Boston Business Journal, March 19, 2002.

Loews Cineplex Entertainment Corporation resulted from the merger of Sony/Loews Theatres and Cineplex Odeon Corporation in May 1998. We treat theatres operating under the name of either Sony or Loews as being owned by the same company.

A movie distributor might decide that only one theatre, within close proximity to another, is allowed to show a particular film, based on a clearance zone. While data are not available on the specific clearance terms of the films in our data set, the existence of such contracts only serves to enhance the predicted impact of geographical distances on similarity. See Filson (2005) for a common-agency model of the distributor–exhibitor relationship and for further institutional detail on this contracting relationship.

To check for the robustness of this control, we also construct HOLIDAYRIGHT, the number of weeks since the preceding holiday, which allows for demand seasonality to take the form of spikes followed by decay rather than smooth increases prior to, and decreases following, a major holiday.

We use aggregate revenue for the whole sample rather than by ij-pair to avoid endogeneity problems.

The correlation coefficient between HOLIDAYDISTANCE and AGGREGATEREVENUE is −0.5523.

A film released on 100 screens will typically cover the major exhibition markets, including Los Angeles, New York, and Boston. In order to compile the data, we cross referenced film-review data from Roger Ebert’s web site, www.rogerebert.suntimes.com, with release data on screen counts from the Internet Movie Database, www.imdb.com.

The lack of price competition is also consistent with tacit coordination among theatres involved in a weekly (or daily) repeated game.

We repeat the estimations replacing HOLIDAYDISTANCE with AGGREGATEREVENUE, then with weekly time dummies. The resulting estimates are qualitatively similar to the main findings described below. Details can be obtained from the authors on request.

See, e.g., Kerin et al. (2006).

When we add differences in average income to the regressions, we find that this difference has a negative and significant impact on similarity when measured within 3-mile radii of each theatre; the impact is statistically insignificant when measured at 5- and 10-mile radii. We find a qualitatively similar pattern when we replace the income variable with differences in population and households, within the varying radii of each theatre. The finding that differences in vacancy rates has a positive impact on similarity holds at 10-mile radii; the coefficient is insignificant at 3- and 5-mile radii.

Predicted values of the indexes are largely within the expected range. We obtain qualitatively similar results on our estimates of the coefficients on the time-invariant variables when we estimate the fixed effects then recover the coefficients on the time-invariant variables in a second-stage estimation.

The holiday distance finding holds for both HOLIDAYDISTANCE and HOLIDAYRIGHT. The aggregate revenue finding holds when we replace HOLIDAYDISTANCE with AGGREGATEREVENUE. As a further robustness check, we replace HOLIDAYDISTANCE with weekly time dummies and find a close relationship between the estimated time dummies and HOLIDAYDISTANCE.

According to Shari Redstone, President of National Amusements, exhibitors typically view screenings of new films one to 3 weeks in advance of release, with a lead time for “event” pictures of sometimes months (Redstone 2004, at 396).

See Chisholm (1993).

References

Beebe, J. H. (1977). Institutional structure and program choices in television markets. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 91, 15–37.

Borenstein, S., & Netz, J. (1999). Why do all the flights leave at 8 am? Competition and departure-time differentiation in airline markets. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 17, 611–640.

Chisholm, D. C. (1993). Asset specificity and long-term contracts: The case of the motion-pictures industry. Eastern Economic Journal, 19, 143–155.

Chisholm, D. C., & Norman, G. (2006). Market size and overlapping characteristics in multi-product firm rivalry. Tufts University mimeo.

Collins, A., Scorcu, A. E., & Zanola, R. (2009). Distribution conventionality in the movie sector: An econometric analysis of cinema supply. Managerial and Decision Economics, 30(8), 517–527.

Danaher, P. J., & Mawhinney, D. F. (2001). Optimizing television program schedules using choice modeling. Journal of Marketing Research, 38, 298–312.

Davis, P. (2006). Spatial competition in retail markets: Movie theaters. RAND Journal of Economics, 37, 964–982.

De Vany, A. S., & Walls, W. D. (2002). Does Hollywood make too many R-rated movies? Risk, stochastic dominance, and the illusion of expectation. Journal of Business, 75, 425–451.

Einav, L. (2007). Seasonality in the U.S. motion picture industry. RAND Journal of Economics, 38, 127–145.

Einav, L., & Orbach, B. Y. (2007). Uniform prices for differentiated goods: The case of the movie-theatre industry. International Review of Law and Economics, 27, 129–153.

Filson, D. (2005). Dynamic common agency and investment: The economics of movie distribution. Economic Inquiry, 43, 773–784.

Hotelling, H. (1929). Stability in competition. Economic Journal, 39, 41–57.

Irmen, A., & Thisse, J.-F. (1998). Competition in multi-characteristics spaces: Hotelling was almost right. Journal of Economic Theory, 78, 76–102.

Jaffe, A. B. (1986). Technological opportunity and spillovers of R&D: Evidence from firms’ patents, profits, and market value. American Economic Review, 76, 984–1001.

Kerin, R. A., Hartley, S. W., Berkowitz, E. N., & Rudelius, W. (2006). Marketing (8th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Netz, J. S., & Taylor, B. A. (2002). Maximum or minimum differentiation? Location patterns of retail outlets. Review of Economics and Statistics, 84, 162–175.

Neven, D. J., & Thisse, J.-F. (1990). On quality and variety competition. In J. J. Gabszewicz, J.-F. Richard, & L. A. Wolsey (Eds.), Economic decision making: Games, and optimisation—Contributions in honour of Jacques H. Dreze econometrics (pp. 175–199). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Petersen, M. A. 2005. Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: Comparing approaches. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 11280.

Pinkse, J., Slade, M. E., & Brett, C. (2002). Spatial price competition: A semiparametric approach. Econometrica, 70, 1111–1153.

Ravid, S. A. (1999). Information, blockbusters, and stars: A study of the film industry. Journal of Business, 72, 463–492.

Ravid, S. A., & Basuroy, S. (2004). Managerial objectives, the R-rating puzzle, and the production of violent films. Journal of Business, 77(Suppl), S155–S192.

Redstone, S. E. (2004). The exhibition business. In J. E. Squire (Ed.), The movie business book (3rd ed., pp. 386–400). New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Rogers, W. H. (1993). Regression standard errors in clustered samples: sg17. Stata Technical Bulletin 13, 19–23 (Reprinted in Stata Technical Bulletin Reprints, Vol. 3, pp. 88–94).

Spence, M. A., & Owen, B. (1977). Television programming, monopolistic competition, and welfare. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 91, 103–126.

Steiner, P. O. (1952). Program patterns and preferences, and the workability of competition in radio broadcasting. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 66, 194–223.

Swami, S., Eliashberg, J., & Weinberg, C. B. (1999). SilverScreener: a modeling approach to movie screen management. Marketing Science, 18, 352–372.

Sweeting, A. (2006). Too much rock and roll? Station ownership, programming and listenership in the music radio industry. Northwestern University Working Paper.

Sweeting, A. (2008). The effects of horizontal mergers on product positioning: Evidence from the music radio industry. Duke University Working Paper.

Tabuchi, T. (1994). Two-stage two-dimensional spatial competition between two firms. Urban Economics, 24, 207–227.

Tirole, J. (1988). The theory of industrial organization. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the DeSantis Center for Motion Picture Industry Studies of Florida Atlantic University College of Business and Economics for providing a grant to fund this research and to Synergy Retail for compiling data used in this paper. For valuable comments and suggestions, we thank Bart Addis, Nicolas de Roos, Thomas Downes, David Garman, F. Andrew Hanssen, Sanjiv Jaggia, Jongbyung Jun, Jordi McKenzie, Zaur Rzakhanov, Alfonso Sanchez-Penalver, Richard Startz, Andrew Sweeting, Chih Ming Tan, Charles Weinberg, Jeffrey Zabel, and seminar participants at Harvard University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Suffolk University, the DeSantis Center Summit Workshop, the International Industrial Organization Conference, the CORE Université Catholique de Louvain Conference on Hotelling’s Legacy and its Future, the UCLA Practitioners Workshop in Motion Pictures Industry Studies, and the University of Sydney Inaugural Screen Economics Research Group Symposium. D. Chisholm is grateful for the hospitality extended while visiting at Harvard during work on this paper. We thank Vicky Huang, Anna Kumysh, and Vidisha Vachharajani for their careful research assistance and Sorin Codreanu for his data-management programming assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: derivation of similarity indexes

Appendix: derivation of similarity indexes

1.1 Angular similarity index

In order to compute the angular similarity index, suppose that theatre i has five screens, and that on a typical day the theatre exhibitor allocates four screening time slots to each auditorium—matinee, twilight, and two evening showings—for a total capacity of 20 daily showings. Suppose further that in week t theatre i is showing four different films, with one of the films on two screens, and the other three on one screen each. Thus, the first film is shown eight times daily using 40% of the showings capacity, while the others are shown four times daily, each using 20% of the capacity. Assume that a total of 10 films are being shown across the entire market that week. Then, vector A it has length 10. The element a nit corresponding to the film showing on two screens equals 0.40; the three elements corresponding to the three films being shown on one screen equal 0.20; the remaining six elements of A it equal zero. The attributes vector A jt for theatre j is constructed analogously.

The angle between the two attributes vectors A it and vector A jt is:

converted to degrees. If the two theatres have an identical set of films, with an identical distribution across screening capacity, the angle between the vectors is zero. The angle between the vectors increases, and approaches 90°, the more dissimilar the theatres are relative to one another in their film screening choices. Rather than work with AV ijt , which is a measure of dissimilarity, we define the normalized angular measure of similarity SA ijt as:

1.2 Matching similarity index

In order to compute the matching similarity index, for each film playing at theatre i in week t, we determine if that film is also playing at theatre j in that week. If so, and if the film is playing four times daily at theatre i and eight times daily at theatre j, the number-of-screenings matches for this film is four. Add this to the other number-of-screenings matches for all other common films across both theatres to derive the total number of screenings in common, S ct and the similarity metric:

where \( \bar{S}_{h} \) is the number of screenings (showings capacity) possible at movie theatre h = i, j. As with the angular measure, the matching measure in (5) is affected by differences in the number of screens between theatre pairs. In order to correct for this potential bias, we normalize S ijt by the maximum degree of similarity \( \bar{S}_{ij} = \left( {{{\left( {\min \left( {\bar{S}_{i} ,\bar{S}_{j} } \right)} \right)^{2} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\left( {\min \left( {\bar{S}_{i} ,\bar{S}_{j} } \right)} \right)^{2} } {\bar{S}_{i} \cdot \bar{S}_{j} }}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} {\bar{S}_{i} \cdot \bar{S}_{j} }}} \right) \) that is possible between theatres i and j, to give the normalized matching similarity measure:

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chisholm, D.C., McMillan, M.S. & Norman, G. Product differentiation and film-programming choice: do first-run movie theatres show the same films?. J Cult Econ 34, 131–145 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-010-9118-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-010-9118-y