Abstract

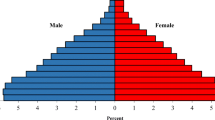

Aging in Latin America and the Caribbean will not proceed along known paths already followed by more developed countries. In particular, the health profile of the future elderly population is less predictable due to factors associated with their demographic past that may haunt them for a long time and make them more vulnerable, even if economic and institutional conditions turn out to be better than what they are likely to be. This paper answers a set of questions regarding the nature and determinants of health status among the elderly in Latin America and the Caribbean using SABE (Survey on Health and Well-Being of Elders), a cross-sectional representative sample of over 10,000 elderly aged 60 and above in private homes in seven major cities in Latin America and the Caribbean. We examine health outcomes such as self-reported health, functional limitations–Activities of Daily Living (ADL’s) and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL’s), obesity (ratio of weight in kilograms to the square of height in centimeters), and self-reported chronic conditions (including diabetes). The findings include: (a) Countries differ in self-reported health but exhibit much less differences in terms of functional limitations. The number of chronic conditions increase with age and is higher among females than among males; (b) On average SABE countries display levels of self-reported diabetes (and obesity) that are as high if not higher than those found in the US; (c) There is evidence, albeit weaker than expected, suggesting deteriorated health and functional status in the region; (d) There is important evidence pointing toward rather strong inequalities (by education and income) in selected health outcomes. Preliminary findings from SABE confirm that Latin America and the Caribbean display peculiarities in the health profile of elderly, particularly with regard to diabetes and obesity. It is important that new policy initiatives begin to seriously target the region’s elderly, especially with an emphasis on the prevention and treatment of diabetes and obesity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A more thorough examination of the aforementioned features can be found in Palloni et al., 2002.

The argument holds, of course, if we assume that the effects of mortality selection are lonely mild and if the effects of changes in behavioral profiles and medical technology (exogenous or not) are only weak.

Because all samples are urban samples, our ability to generalize to the total population is impaired. However, readers should bear in mind that the proportion of the total population living in urban areas in these countries is substantial, varying from close to 100% in Barbados to about 74 or 75% in Mexico and Cuba, respectively (United Nations, 2000). This suggests that our results should not be too different from what we would have obtained had SABE been based on national samples. And, indeed, it has been shown that the demographic profile at least of the samples is quite close to national averages (Palloni & Pelaez, 2002).

In the rest of the paper we refer use the words “country” or “city” to refer to the city samples. By using the word country we are in no way assuming that the SABE data are exactly representative of elderly populations in each of the countries who participated in the project.

For more information on the HRS study and sample see the electronic version of papers by Servais (2004) at http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/docs/dmgt/OverviewofHRSPublicData.pdf or Hauser and Willis (2005) at http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/papers/background/PDR30suppHAUSER.pdf).

To simplify analyses we focus on a single indicator for the presence of ADL and IADL, namely, whether or not individuals declare at least one of them. We could have used the entire frequency distribution and worked instead with the “number of ADL” or the “number of IADL.” But this complicates the analyses unnecessarily since these are discrete, bounded variables and their distribution can only be mimicked by a handful of discrete distributions. Treating them as categories leads to unwieldly results. Finally, because the number of possible ADL (6) and IADL(6) is relatively few, the proportion of individuals declaring 0 turns out to be an excellent predictor of the shape of the entire distribution. Inferences drawn with the simplified indicator chosen here do not change if the dependent variables are fine-tuned (Palloni & McEniry, 2004). The same applies for self-reported health status.

This statement is established by estimating a model where the age effects are constrained to be the same.

Simple analyses of variance (Palloni & McEniry, 2004) reveal that the residual variance explained by country heterogeneity is significant whereas the residual variance explained by age and sex is not.

See Footnote 5.

Analyses of variance (Palloni & McEniry, 2004) suggest that the fraction of total variance explained by country variability is statistically insignificant.

Montevideo is also the only city in the SABE sample where institutionalization of the elderly is more than trivial. The peculiar relation between self-reported health and ADL and IADL in Montevideo might be a result of heavy selection among elderly who remain independent instead of becoming institutionalized.

See Appendix for definition of chronic conditions.

In this paper we reserve the term diabetes to refer to a mixture of diabetes 1 and diabetes mellitus or type 2. However, for the most part those individuals self-reporting diabetes are afflicted by diabetes type 2.

The declining pattern with age is probably a result of the heavier attrition of diabetics as age increases.

See Palloni and McEniry, 2004. Since most of the Barbados population if of African descent, a similar test cannot be applied there.

References

Albala, C., Kain, J., Burrows, R., & Diaz, E. (2000). Obesidad: Un desafio pendiente. Santiago, Chile: Editorial Universitaria, Universidad de Chile.

Albala, C., Lebrao, M. L., Leon Diaz, E. M., Ham-Chande, R., Hennis, A. J., Palloni, A., et al. (2005). The health, well-being and aging (SABE) study: Sample method and profile of the studied population. Pan American Journal of Public Health, 17(5/6), 307–322.

Barker, D. J. P. (1998). Mothers, babies and health in later life (2nd Edition). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

Barrientos, A. (1997). The changing face of pensions in Latin America: Design and prospects of individual capitalization pension plans. Social Policy & Administration, 31(4), 336–353 (December).

Beckett, M., Weinstein, M., Goldman, N., & Yu-Hsuan, L. (2000). Do health interview surveys yield reliable data on chronic illness among older respondents? American Journal of Epidemiology, 151(3), 315–323.

Cynader, Max S. (1994). Mechanisms of brain development and their role in health and well-being. Daedalus, 123(4), 155–165.

Devos, S. (1990). Extended family living among older people in six Latin American countries. Journal of Gerontology, 45(3), S87–S94.

Devos, S., & Palloni, A. (2002). Living arrangements of elderly people around the world. University of Wisconsin-Madison: Center for Demography & Ecology.

Elo, I. T., & Preston, S. H. (1992). Effects of early-life conditions on adult mortality: A review. Population Index, 58(2), 186–212.

Frenk, J., Frejka, T., Bobadilla, J. L., Stern, C., & Sepulveda, J. (1991). Elements for a theory of the health transition. Health Transition Review, 1(1), 21–38.

Goldman, N., I-Fen, L., Weinstein, M., & Yu-Hsung, L. (2002). Evaluating the quality of self-reports on hypertension and diabetes. Princeton University: Office of Population Research.

Hales, C. N., & Barker, D. J. P. (1992). Type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus: The thrifty phenotype hypothesis. Diabetologia, 35, 595–601.

Hales, C. N., Barker, D. J. P., Clark, P. M. S., Cox, L. J., Fall, C., & et al. (1991). Fetal and infant growth and impaired glucose tolerance at age 64. British Medical Journal, 303, 1019–1022.

Hauser, R. M., & Willis, R. J. (2005). http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/papers/background/PDR30suppHAUSER.pdf. This is an electronic version of an article published in Aging, Health, and Public Policy: Demographic and Economic Perspectives, a supplement to Population and Development Review Volume 30. New York: Population Council, 2005.

Health and Retirement Study, HRS Core (Final) (v 1.0) public use dataset (2002). Produced and distributed by the University of Michigan with funding from the National Institute of Aging, (U01 AGO 9740), Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Hertzman, C. (1994). The lifelong impact of childhood experiences: A population health perspective, Daedalus.

Idler, E. L., & Benyamini, Y. (1997). Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38, 21–37.

Idler, E. L., & Kasl, S. (1991). Health perceptions and survival: Do global evaluations of health status really predict mortality? Journal of Gerontology, 46(2), S55–S65.

Idler, E. L., & Kasl, S. V. (1995). Self-ratings of health: Do they also predict change in functional ability? Journal of Gerontology, 50B(6), S344–S353.

Kinsella, K., & Velkoff, V. (2001). An Aging World. US Government Printing Office, Washington, District of Columbia: US Bureau of the Census.

Klinsberg, B. (2000). America Latina: Una region en riesgo, pobreza, inequidad e institucionalidad social. Inter American Development Bank.

Kuh, D., & Ben-Shlomo, Y. (eds). (2004). A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lithell, H. O., McKeigue, P. M., Berglund, L., Mohsen, R., Lithell, U. B., & Leon, D. A. (1996). Relation of size at birth to non-insulin dependent diabetes and insulin concentrations in men aged 50–60 years. British Medical Journal, 312, 406–410.

Manton, K. G., Stallard, E., & Cordel, R. (1997). Changes in age dependence of mortality and disability: Cohort and other determinants. Demography, 34(1), 135–157.

Mesa-Lago, C. (1994). Changing social security in Latin America: Toward alleviating the costs of economic reform. Boulder and London: Lynne Rienner.

Omran, A. R. (1982). Epidemiologic transition. In International Encyclopedia of Population (pp. 172–83). New York: Free Press.

Palloni, A. (2001). Living arrangements of older persons. United Nations Population Bulletin 42/43.

Palloni, A., & Guend, H. (2005). Stature prediction equations for elderly Hispanics by gender and ethnic background developed from SABE data. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences, 60(6), 804–810.

Palloni, A., & McEniry, M. (2004). Health status of elderly people in Latin America. Madison, Wisconsin: Center for Demography and Ecology, University of Wisconsin. Working paper.

Palloni, A., & Pelaez, M. (2002). Survey of health and well-being of elders. Washington, District of Columbia: Pan American Health Organization. Final Report.

Palloni, A., McEniry, M., Guend, H., Davila, A. L., Garcia, A., Mattei, H., & Sanchez, M. (2004). Health among Puerto Ricans: Analysis of a new data set. Center for Demography and Ecology. University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Palloni, A., Pinto, G., & Pelaez, M. (2002). Demographic and health conditions of ageing in Latin America. International Journal of Epidemiology, 31, 762–771.

Palloni, A., Soldo, B., & Wong, R. (2003). The accuracy of self reported anthropometric measures and self reported diabetes in nationally representative samples of older adults in Mexico. Paper presented at the Population Association of America Minneapolis, Minnesota. May 1–3.

Palloni, A., & Wyrick, R. (1981). Mortality decline in Latin America: Changes in the structures of causes of deaths, 1950–1975. Social Biology, 28(3–4), 187–216.

Popkin, B. M. (1993). Nutritional patterns and transition. Population Development Review, 19, 138–157.

Preston, S. H. (1976). Mortality patterns in national populations with special reference to recorded causes of death. New York: Academic.

Ruggles, S. (1996). Living arrangements of the elderly in America. In Tamara K. Hareven (ed), Aging and generational relations over the life course: A historical and cross-cultural perspective (pp. 254–271). New York: Walter de Gruyter.

SABE. Salud y Bienestar en el Adulto Mayor, SABE, version No 1, restricted circulation data set (2003). Produced and distributed by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and the Center for Demography and Health of Aging (CDHA) with the support of the National Institute of Aging, R03 AG15673.

Schaffer, R. H. (2000). The early experience assumption: Past, present, and future. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 24(1), 5–14.

Schechter, S., Beatty, P., & Willis, G. B. (1998). Asking survey respondents about health status: Judgment and response issues. In N. Schwarz, D. Park, B. Knauper, & S. Sudman, (eds), Cognition, Aging, and Self-Reports. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Taylor and Francis.

Sen, A. (2002). Perception versus observation. BMJ, (324), 859–860.

Servais, M. A. (2004). Overivew of HRS public data files for cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis. Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Smith, J. (1994). Measuring health and economic status of older adults in developing countries. Gerontologist, 34(4), 491–496.

Smith, L. A, Branch, L. G., & Scherr, P. A. (1990). Short-term variability of measures of physical function in older people. Journal of American Geriatric Society, 38, 993–998.

Soldo, B. J., & Hill, M. (1995). Family structure and transfer measures in the health and retirement study: Background and overview. Journal of Human Resources, Supplement, 108–137.

Stump, T. E., Clark, D. O., Johnson, R. J., & Wolinsky, F. D. (1977). The structure of health status among Hispanic, African American, and white older adults. Journals of Gerontology, 52B, 49–60 (Special Issue).

United Nations (2000). United Nations demographic yearbook. United Nations, New York: Department of Social and Economic Affairs, Table 7.

Vaupel, J., Manton, K., & Stallard, E. (1979). The impact of heterogeneity in individual frailty on the dynamics of mortality. Demography, 16(3), 439–454.

Wallace, R. B. H. A. R. (1995). Overview of the health measures in health and retirement study. Journal of Human Resources, Supplement, 84–107.

Wray, L. A., Herzog, A. R., & Park, D. C. (1996). Physical health, mental health, and function among older adults. Paper presented at the Annual Meetings of the Gerontological Society of America, November, Washington, District of Columbia.

Wray, L. A., & Lynch, J. W. (1998). The role of cognitive ability in links between disease severity and functional ability in middle-aged adults. Paper presented at the Annual Meetings of the Gerontological Society of America, November, Philadelphia.

Acknowledgments

This paper is only possible thanks to the collaboration of the principal investigators of the SABE study, Cecilia Albala, Anselm Hennis, Roberto Ham, Maria Lucia Lebrao, Esther de Leon, Edith Pantelides, and Omar Pratts. We are thankful to Dr. Guido Pinto for many discussions and for extensive work on the data set and to Dr. Martha Pelaez, from the Pan American Health Organization, without whose initiative the project would not have been possible. The research for this paper was supported by NIA grants R01 AG16209 and R03 AG15673 to Palloni. Both authors work in the Center for Demography and Ecology supported by core grant P30 HD05876, and in the Center Core supported by core grant P30 AG17266.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix

ADL and IADL

1.1. ADL’s:

-

Walking across the room

-

Dressing

-

Bathing

-

Eating

-

Getting in and out of bed

-

Using bathroom

1.2 . IADL’s

-

Preparing meals

-

Managing money

-

Difficulty with getting to places (only in SABE)

-

Buying food or clothing

-

Using the phone (in SABE asked of those who had a phone)

-

Doing heavy housework (only in SABE)

-

Doing light housework (only in SABE)

-

Taking medicines

For multivariate analyses, we used only those SABE IADLs that were strictly comparable with HRS: preparing meals, managing money, buying food or clothing, using the phone, and taking medicine.

Chronic Conditions

-

Arthritis

-

Cancer

-

Diabetes

-

Respiratory Illness

-

Heart Disease

-

Stroke

Targets, Spouses and Proxies

In three countries (Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay) only one individual per household was interviewed. In two countries, Brazil and Mexico, interviewers proceeded to interview all individuals 60 and older found in selected household. In virtually all these cases, the additional interviews corresponded to spouses (one per household). In Cuba interviewers selected a target individual and a spouse.

In our analyses we include all individuals interviewed. This has the advantage of maximizing observation at the expenses of introducing dependence of observations in the countries where more than one individual per household was interviewed. In order to protect our inferences we repeated some of the analyses using clustering procedures to adjust for lack of independence but since the inferences remain unchanged we have chosen to present results based on the larger samples.

Sampling Weights

Only the sample from Santiago is self-weighted. All others require weights to expand the sample population to the city population. Since in two countries no sample weights have been calculated we chose to ignore them in all the others. However, to ensure that none of our conclusions was sensitive to this choice, we proceeded to re-estimate models using sampling weights for those countries that had them available. None of the inferences changed, and it is highly unlikely that they will even in the countries where there were no weights available yet.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Palloni, A., McEniry, M. Aging and Health Status of Elderly in Latin America and the Caribbean: Preliminary Findings. J Cross Cult Gerontol 22, 263–285 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-006-9001-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-006-9001-7