Abstract

Purpose

Mouse embryonic fibroblast feeder layers (MEF) have conventionally been used to culture and maintain the pluripotency of embryonic stem cells (ESC). This study explores the potential of using a novel human endometrial cell line to develop a non-xeno, non-contact co-culture system for ESC propagation and derivation. Such xeno-free systems may prove essential for the establishment of clinical grade human ESC lines suitable for therapeutic application.

Methods

A novel line of human endometrial cells were seeded in a 6-well dish. Filter inserts containing mouse ESCs were placed on these wells and passaged 2–3 times per week. Inner cell masses derived from mouse blastocysts were also cultured on transwells in the presence of the feeder layer. In both cases, staining for SSEA-1, SOX-2, OCT-4 and alkaline phosphatase were used to monitor the retention of stem cells.

Results

ESC colonies retained their stem cell morphology and attributes for over 120 days in culture and 44 passages to date. Inner cell mass derived ESC cultures were maintained in a pluripotent state for 45 days, through 6 passages with retention of all stem cell characteristics. The stem cell colonies expressed stem cell specific markers SSEA-1, Sox 2, Oct-4 and alkaline phosphatase. Upon removal of the human feeder layer, there was a distinct change in cell morphology within the colonies and evidence of ESC differentiation.

Conclusions

Human feeder layers offer a simple path away from the use of MEF feeder cells or MEF conditioned medium for ESC culture. Furthermore, indirect co-culture using porous membranes to separate the two cell types can prevent contamination of stem cell preparations with feeder cells during passaging.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are derived from the inner cell mass (ICM) of mammalian blastocysts. Original studies in the early 1980’s showed that stem cells derived from the inner cell mass of mouse blastocysts were pluripotent and could proliferate continuously in an undifferentiated state [13, 22]. The first derivation of a human ESC line was reported by Thomson et al. [31]. The human embryonic stem cell (hESC) line retained its pluripotency during in vitro propagation and was capable of differentiation into all three germ layers, i.e. endoderm, mesoderm and ectoderm. Derivation of human ESC lines in early studies required the use of a mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) feeder layer [25, 31]. Cytokines, growth factors, and extracellular matrix (ECM) components, as well as a myriad of as yet undefined components in the MEF cell culture milieu, apparently have the ability to sustain the pluripotency of human, as well as monkey and mouse ESC in vitro.

The unique ability of ESCs to differentiate into a desired cell lineage with specific signaling makes them an invaluable tool for research in drug development, cell regeneration and delivery of gene therapies. For such applications, ESC culture with animal feeder cell layers may be undesirable due to the potential risk of pathogen transmission and viral infection [4, 26, 27]. For the therapeutic potential of ESCs to be effectively exploited, it will likely be necessary to develop “clinical grade” ESC lines that have been cultivated without direct exposure to animal tissues.

Attempts to overcome this problem have led to the cultivation of hESCs in MEF conditioned media [21, 33] or on an extracellular matrix with growth factors [19]. Others have suggested that hESC encapsulation and 3-D culture in a hydrogel in combination with MEF –conditioned medium may provide some benefit, allowing self renewal without passaging [15]. Xeno and feeder-free culture in chemically defined medium supplemented with ECMs, high levels of growth factors and signaling molecules is another attractive path towards creating therapeutic grade hESC lines, standardizing culture conditions and reducing work load. [2, 4, 5, 21, 33–35]. However, such media systems can be complex, costly and require diligent attention to prevent undesired differentiation of ESC colonies on the periphery of the cultures.

An alternate approach has been the use of a variety of different human cell types as feeder layers for co-culture of ESCs. The cells used include fetal fibroblasts [12, 28], foreskin fibroblasts [3, 7, 16], placental fibroblasts [14], human marrow stromal cells [6] and human endometrial cells [20]. Commercially available human embryonic stem cell lines themselves may also be useful as feeder cells for propagation of other hESC lines as well as for the derivation of new hESC lines from human embryos [32]. Still, any type of direct contact between the hESCs and the feeder cell layer, even if of human origin, carries the potential threat of contamination with the feeder cell population, making their use for future therapeutic transplantation into patients more difficult.

In the present study we describe a non-contact co-culture model for ESC propagation using a novel human endometrial cell line as a potential alternative to MEF feeder cells. We tested this model first for propagation of a commercially available mouse ESC line and then for establishment of ESC cultures from the inner cell mass of mouse blastocysts.

Materials and methods

Human endometrial cell line

The human endometrial cell line described in this investigation was initially isolated from benign proliferative endometrium. This cell line has since undergone more than 45 passages, retaining its epithelial cell morphology and characteristics [10, 11]. The endometrial cell line was maintained in modified α Minimum Essential Medium supplemented with 5 % heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies; Grand Island, NY). Culture flasks were incubated in a humidified chamber at 37 °C with 6 % CO2. The cell line was passaged every 4–5 days.

Transwell permeable supports (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY) with 12 mm polyester (PET) membranes (pore size 0.4 μM) were used for co-culture in 6-well plates. The porous membrane filters are permeable and transparent, allowing the sharing of media and secretions while creating a physical separation between the two cell types. Human endometrial cells were seeded into the dish at a concentration of either 15,000 or 30,000 cells per well. The endometrial feeder layers were utilized for ESC co-culture when they were 40–50 % confluent. The membrane insert with ESC colonies was transferred to a fresh endometrial feeder when the initial feeder layer reached ~ 75 % confluence.

Mouse embryonic stem cell line

The culture medium for all stem cell work was ESC-Sure DMEM (Applied Stem Cell; Menlo Park, CA) with 20 % ESC-Sure fetal bovine serum (FBS; Life Technologies; Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10 ng/ml mouse leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF; Stem Cell Technologies; BC, Canada), 2.0 mM L-glutamine, 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids, 1.0 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.1 mM ß mercaptoethanol, 100units/mL penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (all from Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA).

A commercially available mouse ESC line ASE-9005 was purchased (Applied Stem Cell; Sunnyvale, CA). Embryonic stem cells were seeded on the porous membrane of the Transwell insert at a concentration of 2–3000 cells/well. A media half –change was performed every 48 h. Cultures were monitored daily and photographed. ESC cultures were passaged when colony diameter reached 100-120 μm. Colonies were trypsinized and new wells were seeded. Inserts with ESC colonies were moved to wells with new feeder layers when the endometrial monolayers approached 75 % confluence.

Mouse blastocyst derived stem cells

One cell mouse zygotes from a B6D2F1 x B6C3F1 cross were purchased for stem cell isolation (Charles River Laboratories; Wilmington, MA). Embryos were thawed and cultured in Global medium (Life Global; Guilford, CT) supplemented with 10 % Serum Protein Supplement (SPS; Trumbull, CT) for 6 days. On day 6, the zona pellucida was removed from blastocysts using mechanical pipetting along with laser opening of the zonae. Embryos were placed on the Transwell inserts and co-cultured in stem cell medium with the human endometrial feeder layer. ICM outgrowths formed 1–2 days after plating were microsurgically excised. The ICM clumps were placed in a 20 μl drop of 0.5 % trypsin/EDTA solution for 3 min, after which an equal volume of FBS was added to inactivate the enzyme. The ICM clumps were then disaggregated using a drawn glass micropipette. The dispersed ICM cells were then seeded into a new Transwell insert and placed on a fresh endometrial feeder layer. Five days after the seeding of ICM cells, dome-like colonies started to appear. Individual ESC-like colonies were manually selected and once again disaggregated with trypsin-EDTA. This process was repeated for further expansion of the ICM derived stem cells. However, it was not necessary to manually select colonies after the second passage. Instead, the entire filter was trypsinized. Any colonies lifting off were collected, disaggregated and placed in new Transwell inserts. Colonies were passaged after reaching diameters of 100–120 μm. At each passage the insert with stem cells was placed on a fresh feeder of endometrial cells.

Characterization of embryonic stem cells

The mouse ASE-9005 ESC line and the ICM-derived stem cell cultures were tested for pluripotency using a commercially available kit for mouse ESC characterization (Applied Stem Cell; Menlo Park, CA). We tested for four markers of undifferentiated mouse stem cells, namely expression of SSEA-1, Sox-2, and Oct4, as well as alkaline phosphatase activity.

Staining was performed as per manufacturer’s instructions with slight modifications to accommodate ESC growth on membrane filter inserts. Membrane inserts with ESC cultures were carefully rinsed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) before staining, taking care not to dislodge the colonies. The ESC colonies were then fixed on the membrane by adding 4 drops of fixing solution. After one hour at room temperature, fixative was removed with three 5 min rinses with PBS. Approximately 4 drops of permeablizing solution were placed on top of each membrane for 30 min at room temperature, followed by another PBS rinse. Blocking solution was applied to each membrane for one hour before application of primary antibodies. Aliquots (35-40ul) of SSEA-1, SOX-2 and Oct-4 were placed on separate glass slides. Membranes with ESC colonies were carefully cut out of the Transwell inserts and placed colony side down on the different slides with primary antibody. Slides were enclosed in a humidified chamber and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The next morning, the membranes were rinsed before application of the appropriate secondary antibody for one hour at room temperature. This last incubation and all subsequent steps were performed in the dark. The specificity of each antibody was verified with concurrently run negative controls. Upon completion of labeling with secondary antibodies, the membranes were once again rinsed. A DNA staining solution was then applied for 8–10 min. Membranes were placed colony side up on slides with mounting solution and cover slipped. Confocal laser microscopy with optical sectioning was used to examine immunoflourescent staining for stem cell markers.

Alkaline phosphatase in ESC cultures was detected using the rapid sensitive alkaline phosphatase test provided in the stem cell characterization kit. Alkaline phosphatase test solution (80–100 μl) was placed directly on the ESC colonies growing on the membrane insert. After 2 h of staining at room temperature, the membrane was mounted on a glass slide and cover slipped. Alkaline phosphatase activity in colonies was visualized using light microscopy.

Results

In this investigation we explored the possibility of using a novel human endometrial cell line as a feeder layer for ESC culture. We elected to use the Costar Transwell dishes in developing this co-culture model to prevent direct contact between the human feeder layer and the mouse stem cells. This prevented contamination of our stem cell cultures with the feeder cells. Testing was initially done by following the growth of an established stem cell line, ASE 9005, with the endometrial feeder. We later determined that this human feeder was also able to support growth of stem cells derived from the inner cell mass of mouse blastocysts.

The ASE-9005 mESC line adapted quite nicely to growth on the membrane suspended above the endometrial cell feeder (Fig. 1a-c). ESC colonies proliferated rapidly, necessitating at least two passages per week. With time in culture, the growth rate accelerated, requiring the reduction of the number of cells seeded onto the insert. Seeding with 2–3000 cells appeared to be optimal. Colony morphology was consistent through passages. Stem cells formed a tight amorphous mass of cells with a distinct border and paralleled the morphology typically observed in our laboratory with ESC grown directly on a MEF feeder layer (Fig. 1d). Cells had the high nucleus/cytoplasm ratio associated with pluripotent cells. We often noted signs of differentiation if colonies on the insert were allowed to grow much past a diameter of 120 μM. Cells started to spread, flatten and there was a loss of border integrity. Cells on the edge of the larger colonies tended to round up and cytoplasmic membranes of individual cells became more clearly evident.

a-c Mouse embryonic stem cell line ASE-9005 cultured on Transwell membrane inserts, with a human endometrial cell feeder layer in the outer well. Colonies from passage 44 shown 24, 48 and 72 h after seeding displayed typical ESC colony morphology. Colonies measuring 80–100 μM were selected for trypsinization and further expansion. d Typical morphology of mESC cultured on a MEF feeder layer is shown 72 h after plating

This culture model facilitated extended passaging and expansion of ESC colonies, without feeder cell contamination. Colonies could be selected and removed from the porous membrane insert with a glass micropipette. With carefully controlled passaging, ESC colonies have retained their stem cell morphology and attributes for over 120 days in culture and 44 passages to date. The stem cell colonies cultured in our non-contact co-culture model expressed stem cell specific markers SSEA-1, Sox 2, Oct-4 and alkaline phosphatase (Fig. 2). Light microscopic scanning of the membranes revealed that over 80 % of the colonies were strongly positive for alkaline phosphatase activity. We were able to successfully cryopreserve these stem cells at various passages. Upon thawing and re-plating in fresh co-culture wells, approximately 70 % of cells were able to attach to the membrane surface and form new ESC colonies. The newly propagated colonies, as well as sub-passages continued to express stem cell specific markers.

ESC colonies at passage 44 were stained to confirm maintenance of stem cell characteristics after non-contact co-culture with the human endometrial feeder cells a Staining for alkaline phosphatase activity b-d Immunoflouresecent staining for expression of stem cell markers Oct-4, SSEA-1 and Sox-2, respectively

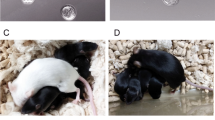

The second question of obvious importance was whether or not this system would be effective for derivation and propagation of stem cells isolated from embryos. To this end, we isolated the ICMs from 21 day 6 mouse blastocysts using laser excision and microsurgical dissection. Amongst the isolated ICMs plated in groups on the membrane inserts, 19 of 21 were able to attach and propagate. The human feeder supported expansion of all of the ESC cultures initiated. The ICM derived cultures were monitored daily for morphologic changes and stained on day 4 and 7 post-isolation for stem cell specific markers. Staining was strong for SSEA-1, Sox-2 and alkaline phosphatase activity. Staining for Oct-4 was distinctly present and increased in intensity over the first few passages. ICM derived ESC cultures were maintained in a pluripotent state for 45 days, through 6 passages with retention of all stem cell characteristics (Fig. 3). Upon removal of the human feeder layer, there was a distinct change in cell morphology within the colonies and evidence of ESC differentiation. After 10 days growth without the feeder, we observed beating cardiomyocytes in one of our stem cell preparations.

Discussion

MEF feeder layers have long been an effective and reliable tool for derivation and propagation of ESCs from various animal species, as well as humans. The search for improved methods and efforts to develop non-xenogenic culture systems has led to interest in human-derived feeder cells. In this study, we describe a new non-contact co-culture system for the cultivation of mouse ESCs that uses a novel human endometrial cell line. This cell line has previously been demonstrated to have embryotrophic properties [11] and to secrete numerous cytokines [10]. The cell line has been used for the co-culture of human embryos during IVF to enhance pregnancy outcomes in patients with repeated IVF failures and/or poor quality embryos [8]. For these reasons, we believed it might be a good alternative to animal feeder cell layers, like MEF, for ESC growth.

Human endometrial cells are known to express various factors including growth factors like IGF, EGF, TGF ß, the cytokines CSF, LIF, Inteleukin-1 and 6 [10, 23, 30], as well as cell adhesion molecules like ECM and integrins [24, 29] for controlling embryonic development and successful implantation in the reproductive track. All of these factors are known to be key regulators in maintaining the ESCs in an undifferentiated state [3].

Our laboratory has already shown that isolated mouse ICMs, both fresh and vitrified, can be successfully cultivated in a non-contact system with MEFs as a feeder [9]. Unlike MEF cells, which are primary cultures, the human endometrial cells used in our model have the advantage of being a permanent, established epithelial cell line. The cells are easily passaged, can be grown indefinitely and can be cryopreserved to ensure consistency in feeder layer preparation. The Transwell membrane inserts with ESC colonies can be moved to fresh feeder layers as needed without having to trypsinize the ESC colonies. Separation of the ESC colonies from the endometrial feeder layer via the porous membrane facilitated colony passaging and prevented carryover of feeder cells to the ESC preparation, a problem inherent to techniques involving the direct growth of ESCs on feeder layers. Colonies could be selectively removed from the membrane with a micropipette and then enzymatically dispersed for seeding of new ESC cultures.

Other published studies have used porous membranes as a physical barrier, with ESCs and feeder cells seeded on opposite surfaces of the membrane [17, 18]. Both cell types were therefore more closely juxtapositioned than in our study. Kim et al. showed migration of MEF and STO feeder cells upward through the filter depending on pore size of the membrane. A pore size of 1 μM or less was necessary to eliminate direct interaction between the feeder layer and the hESC. Abrahams et al. used an indirect co-culture model similar to ours to propagate human pluripotent stem cells with a human fibroblast feeder layer. These authors observed that human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) did not attach to the PET membrane unless it was pre-coated with human fibroblast-derived extracellular matrix [1]. We had no such problem with mESC attachment to the PET membrane and our mESC line was successfully propagated in an undifferentiated state for over four months. It may well be that hESC are more sensitive than mESC, perhaps requiring closer contact and/or the presence of extracellular matrix extracts. Another consideration is that feeder layers of epithelial nature like our cell line may be contributing specific factors and/or matrix components that are particularly beneficial.

In a comparative study of the effectiveness of different feeder cell preparations for human ESC propagation, fetal muscle, fetal skin and adult skin were amongst the top ranking feeders [28]. Primary feeder layers established from adult glandular endometrium and adult stromal endometrium explants were found to be non-supportive of hESC growth. In contrast, Lee et al. were able to successfully derive and maintain hESCs through 55 passages on primary cultures derived from enzymatically digested adult human endometrium. The hESCs exhibited all typical hESC traits, stem cell markers and the ability to differentiate. Investigators concluded that expression of embryotrophic factors and extracellular matrix components by endometrial cells may prove to be advantageous in establishing stem cell lines. In all of the aforementioned studies, the hESCs were in direct contact with the human feeder cell layer and in most of the studies the feeders were mitotically inactivated. Our culture system is unique in that we have the benefit of an actively proliferating feeder layer with its associated secretions, conditioning the ESC medium without direct contact between the two proliferating cell types.

The results of this study demonstrate that our human endometrial feeder layer is capable of sustaining the undifferentiated growth of mouse ESCs. Additionally, we establish that direct contact between stem cells and feeder cells is unnecessary for their successful proliferation and for maintenance of pluripotency. The system facilitated the maintenance of the mouse ESC line for over 120 days through 44 passages, during which time the ESCs retained expression of SSEA-1, Sox-2, and OCT-4 and were positive for alkaline phosphatase activity. Initial results also indicated that our non-contact co-culture system was useful for deriving ESC cultures from the inner cell mass of blastocyst stage embryos.

One of the limitations of this study was our lack of access to human stem cell lines for further testing of our culture model. We feel our data support the potential application of this type of non-contact, non-xeno model for hESC work. We are currently in the process of approaching regulatory bodies at our clinic to obtain the necessary permissions to expand this work to include stem cell derivation from frozen human embryos donated for research. We hope that such a study will help to validate our human endometrial cell line as a feeder layer suitable for the growth of hESCs in a xeno-free, non-contact co-culture system as presented in this preliminary investigation.

Conclusion

Further exploration of this culture model for derivation and propagation of clinical grade hESC lines is warranted. Movement away from animal cell feeders may aid in the transition of ESC research to the clinical setting and to stem cell-based therapies. Chemically defined media formulations completely free of any animal products still need further refinement and optimization to become widely accepted for large scale production of stem cells. In the mean time, human feeder layers offer a simple path away from the use of MEF feeder cells or MEF conditioned medium for ESC culture.

References

Abraham S, Sheridan SD, LLaurent LC, Albert K, Stubban C, Ulitsky I, Miller B, Loring JF, Rao RR. Propagation of human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells in an indirect co-culture system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;211–216.

The International Stem Cell Initiative Consortium, Akopian V, Andrews PW, Beil S, Benvenisty N, Brehm J, Christie M, et al. Comparison of defined culture systems for feeder cell free propagation of human embryonic stem cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2010;46(3–4):247–58.

Amit M, Margulets V, Segev H, Shariki K, Laevsky I, Coleman R, et al. Human feeder layers for human embryonic stem cells. Biol Reprod. 2003;68(6):2150–6. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.102.012583.

Amit M, Shariki C, Margulets V, Itskovitz-Eldor J. Feeder layer- and serum-free culture of human embryonic stem cells. Biol Reprod. 2004;70(3):837–45.

Beattie GM, Lopez AD, Bucay N, Hinton A, Firpo MT, King CC, et al. Activin a maintains pluripotency of human embryonic stem cells in the absence of feeder layers. Stem Cells. 2005;23(4):489–95. doi:10.1634/stemcells.2004-0279.

Cheng L, Hammond H, Ye Z, Zhan X, Dravid G. Human adult marrow cells support prolonged expansion of human embryonic stem cells in culture. Stem Cells. 2003;21(2):131–42. doi:10.1634/stemcells.21-2-131.

Choo AB, Padmanabhan J, Chin AC, Oh SK. Expansion of pluripotent human embryonic stem cells on human feeders. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004;88(3):321–31. doi:10.1002/bit.20247.

Desai N, Abdelhafez F, Bedaiwy MA, Goldfarb J. Live births in poor prognosis IVF patients using a novel non-contact human endometrial co-culture system. Reprod BioMed Online. 2008;16(6):869–74.

Desai N, Xu J, Tsulaia T, Szeptycki-Lawson J, AbdelHafez F, Goldfarb J, Falcone T. Vitrification of mouse embryo-derived ICM cells: a tool for preservign embryonic stem cell potential? Journal of assisted reproduction and genetics. 2010;93–99.

Desai NN, Goldfarb JM. Growth factor/cytokine secretion by a permanent human endometrial cell line with embryotrophic properties. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1996;13(7):546–50.

Desai NN, Kennard EA, Kniss DA, Friedman CI. Novel human endometrial cell line promotes blastocyst development. Fertil Steril. 1994;61(4):760–6.

Draper JS, Moore HD, Ruban LN, Gokhale PJ, Andrews PW. Culture and characterization of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2004;13(4):325–36. doi:10.1089/1547328041797525.

Evans MJ, Kaufman MH. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature. 1981;292(5819):154–6.

Genbacev O, Krtolica A, Zdravkovic T, Brunette E, Powell S, Nath A, et al. Serum-free derivation of human embryonic stem cell lines on human placental fibroblast feeders. Fertil Steril. 2005;83(5):1517–29. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.01.086.

Gerecht S, Burdick JA, Ferreira LS, Townsend SA, Langer R, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Hyaluronic acid hydrogel for controlled self-renewal and differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(27):11298–303. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703723104.

Hovatta O, Mikkola M, Gertow K, Stromberg AM, Inzunza J, Hreinsson J, et al. A culture system using human foreskin fibroblasts as feeder cells allows production of human embryonic stem cells. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(7):1404–9.

Hwang S, Kan S, Lee S, Lee T, Suh W, Shim S, Lee D, Raite L, Kim K, Lee S. The expansion of human ES and iPS cells on porous membranes and proliferating human adipose-derived feeder cells. Biomaterials. 2010.

Kim S, EAhn SE, Lee JH, Lim D-S, Kim K-S, Chung H-M, et al. A novel culture technique for human embryonic stem cells using porous membranes. Stem Cells. 2007;25(10):2602–9.

Klimanskaya I, Chung Y, Meisner L, Johnson J, West MD, Lanza R. Human embryonic stem cells derived without feeder cells. Lancet. 2005;365(9471):1636–41. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66473-2.

Lee JB, Lee JE, Park JH, Kim SJ, Kim MK, Roh SI, et al. Establishment and maintenance of human embryonic stem cell lines on human feeder cells derived from uterine endometrium under serum-free condition. Biol Reprod. 2005;72(1):42–9.

Mallon BS, Park KY, Chen KG, Hamilton RS, McKay RD. Toward xeno-free culture of human embryonic stem cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38(7):1063–75.

Martin GR. Isolation of a pluripotent cell line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78(12):7634–8.

Polan ML, Simon C, Frances A, Lee BY, Prichard LE. Role of embryonic factors in human implantation. Hum Reprod. 1995;10 Suppl 2:22–9.

Reddy KV, Mangale SS. Integrin receptors: the dynamic modulators of endometrial function. Tissue and Cell. 2003;35(4):260–73.

Reubinoff BE, Pera MF, Fong CY, Trounson A, Bongso A. Embryonic stem cell lines from human blastocysts: somatic differentiation in vitro. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18(4):399–404. doi:10.1038/74447.

Richards M, Fong CY, Chan WK, Wong PC, Bongso A. Human feeders support prolonged undifferentiated growth of human inner cell masses and embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20(9):933–6.

Richards M, Fong CY, Tan S, Chan WK, Bongso A. An efficient and safe xeno-free cryopreservation method for the storage of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2004;22(5):779–89.

Richards M, Tan S, Fong CY, Biswas A, Chan WK, Bongso A. Comparative evaluation of various human feeders for prolonged undifferentiated growth of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2003;21(5):546–56. doi:10.1634/stemcells.21-5-546.

Selam B, Kayisli UA, Garcia-Velasco JA, Arici A. Extracellular matrix-dependent regulation of Fas ligand expression in human endometrial stromal cells. Biol Reprod. 2002;66(1):1–5.

Simon C, Frances A, Lee BY, Mercader A, Huynh T, Remohi J, et al. Immunohistochemical localization, identification and regulation of the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in the human endometrium. Hum Reprod. 1995;10(9):2472–7.

Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, Waknitz MA, Swiergiel JJ, Marshall VS, et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282(5391):1145–7.

Wang Q, Fang ZF, Jin F, Lu Y, Gai H, Sheng HZ. Derivation and growing human embryonic stem cells on feeders derived from themselves. Stem Cells. 2005;23(9):1221–7. doi:10.1634/stemcells.2004-0347.

Xu C, Inokuma MS, Denham J, Golds K, Kundu P, Gold JD, et al. Feeder-free growth of undifferentiated human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19(10):971–4.

Xu C, Rosler E, Jiang J, Lebkowski JS, Gold JD, O'Sullivan C, et al. Basic fibroblast growth factor supports undifferentiated human embryonic stem cell growth without conditioned medium. Stem Cells. 2005;23(3):315–23. doi:10.1634/stemcells.2004-0211.

Xu RH, Sampsell-Barron TL, Gu F, Root S, Peck RM, Pan G, et al. NANOG is a direct target of TGFbeta/activin-mediated SMAD signaling in human ESCs. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3(2):196–206. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.001.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Julia Szeptycki and Jing Xu for ICM isolation and Rashmi Anand for stem cell culture.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Capsule We developed a non-contact co-culture system using a novel human endometrial cell line that allowed propagation of embryonic stem cells. This offers a simple path away from the use of mouse embryonic feeder (MEF) cells for stem cell culture.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Desai, N., Ludgin, J., Goldberg, J. et al. Development of a xeno-free non-contact co- culture system for derivation and maintenance of embryonic stem cells using a novel human endometrial cell line. J Assist Reprod Genet 30, 609–615 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-013-9977-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-013-9977-1