Abstract

Purpose

Embryos generated from oocytes which have been vitrified have lower blastocyst development rates than embryos generated from fresh oocytes. This is indicative of a level of irreversible damage to the oocyte possibly due to exposure to high cryoprotectant levels and osmotic stress. This study aimed to assess the effects of vitrification on the mitochondria of mature mouse oocytes while also examining the ability of the osmolyte glycine, to maintain cell function after vitrification.

Methods

Oocytes were cryopreserved via vitrification with or without 1 mM Glycine and compared to fresh oocyte controls. Oocytes were assessed for mitochondrial distribution and membrane potential as well as their ability to fertilise. Blastocyst development and gene expression was also examined.

Results

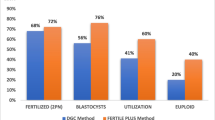

Vitrification altered mitochondrial distribution and membrane potential, which did not recover after 2 h of culture. Addition of 1 mM glycine to the vitrification media prevented these perturbations. Furthermore, blastocyst development from oocytes that were vitrified with glycine was significantly higher compared to those vitrified without glycine (83.9 % vs. 76.5 % respectively; p < 0.05) and blastocysts derived from oocytes that were vitrified without glycine had significantly decreased levels of IGF2 and Glut3 compared to control blastocysts however those derived from oocytes vitrified with glycine had comparable levels of these genes compared to fresh controls.

Conclusion

Addition of 1 mM glycine to the vitrification solutions improved the ability of the oocyte to maintain its mitochondrial physiology and subsequent development and therefore could be considered for routine inclusion in cryopreservation solutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Acton BM, Jurisicova A, Jurisica I, Casper RF. Alterations in mitochondrial membrane potential during preimplantation stages of mouse and human embryo development. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10:23–32.

Agca Y, Liu J, Rutledge JJ, Critser ES, Critser JK. Effect of osmotic stress on the developmental competence of germinal vesicle and metaphase II stage bovine cumulus oocyte complexes and its relevance to cryopreservation. Mol Reprod Dev. 2000;55:212–9.

Anchamparuthy VM, Pearson RE, Gwazdauskas FC. Expression pattern of apoptotic genes in vitrified-thawed bovine oocytes. Reprod Domest Anim. 2010;45:e83–90.

Baltz JM. Media composition: salts and osmolality. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;912:61–80.

Baltz JM, Tartia AP. Cell volume regulation in oocytes and early embryos: connecting physiology to successful culture media. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16:166–76.

Barnett DK, Bavister BD. What is the relationship between the metabolism of preimplantation embryos and their developmental competence? Mol Reprod Dev. 1996;43:105–33.

Barnett DK, Kimura J, Bavister BD. Translocation of active mitochondria during hamster preimplantation embryo development studied by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Dev Dyn. 1996;205:64–72.

Barnett DK, Clayton MK, Kimura J, Bavister BD. Glucose and phosphate toxicity in hamster preimplantation embryos involves disruption of cellular organization, including distribution of active mitochondria. Mol Reprod Dev. 1997;48:227–37.

Brevini TA, Vassena R, Francisci C, Gandolfi F. Role of adenosine triphosphate, active mitochondria, and microtubules in the acquisition of developmental competence of parthenogenetically activated pig oocytes. Biol Reprod. 2005;72:1218–23.

Brown KW, Villar AJ, Bickmore W, Clayton-Smith J, Catchpoole D, Maher ER, et al. Imprinting mutation in the Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome leads to biallelic IGF2 expression through an H19-independent pathway. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:2027–32.

Chen SU, Lien YR, Chao K, Lu HF, Ho HN, Yang YS. Cryopreservation of mature human oocytes by vitrification with ethylene glycol in straws. Fertil Steril. 2000;74:804–8.

Chen C, Han S, Liu W, Wang Y, Huang G. Effect of vitrification on mitochondrial membrane potential in human metaphase II oocytes. J Assist Reprod Genet 2012.

Chi MM, Hoehn A, Moley KH. Metabolic changes in the glucose-induced apoptotic blastocyst suggest alterations in mitochondrial physiology. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;283:E226–32.

Cobo A. Oocyte vitrification: a watershed in ART. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:600–1.

Cobo A, Diaz C. Clinical application of oocyte vitrification: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:277–85.

Cobo A, Kuwayama M, Perez S, Ruiz A, Pellicer A, Remohi J. Comparison of concomitant outcome achieved with fresh and cryopreserved donor oocytes vitrified by the Cryotop method. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:1657–64.

Cummins JM. The role of mitochondria in the establishment of oocyte functional competence. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;115 Suppl 1:S23–9.

Dawson KM, Baltz JM. Organic osmolytes and embryos: substrates of the Gly and beta transport systems protect mouse zygotes against the effects of raised osmolarity. Biol Reprod. 1997;56:1550–8.

Dawson KM, Collins JL, Baltz JM. Osmolarity-dependent glycine accumulation indicates a role for glycine as an organic osmolyte in early preimplantation mouse embryos. Biol Reprod. 1998;59:225–32.

DeChiara TM, Efstratiadis A, Robertson EJ. A growth-deficiency phenotype in heterozygous mice carrying an insulin-like growth factor II gene disrupted by targeting. Nature. 1990;345:78–80.

Eroglu A, Toth TL, Toner M. Alterations of the cytoskeleton and polyploidy induced by cryopreservation of metaphase II mouse oocytes. Fertil Steril. 1998;69:944–57.

Forman EJ, Li X, Ferry KM, Scott K, Treff NR, Scott Jr RT. Oocyte vitrification does not increase the risk of embryonic aneuploidy or diminish the implantation potential of blastocysts created after intracytoplasmic sperm injection: a novel, paired randomized controlled trial using DNA fingerprinting. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:644–9.

Gardner DK, Lane MW, Lane M. EDTA stimulates cleavage stage bovine embryo development in culture but inhibits blastocyst development and differentiation. Mol Reprod Dev. 2000;57:256–61.

Gardner DK, Lane M, Watson AJ, editors. A laboratory guide to the mammalian embryo. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004.

Gualtieri R, Mollo V, Barbato V, Fiorentino I, Iaccarino M, Talevi R. Ultrastructure and intracellular calcium response during activation in vitrified and slow-frozen human oocytes. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:2452–60.

Heggeness MH, Simon M, Singer SJ. Association of mitochondria with microtubules in cultured cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978;75:3863–6.

Isachenko V, Alabart JL, Nawroth F, Isachenko E, Vajta G, Folch J. The open pulled straw vitrification of ovine GV-oocytes: positive effect of rapid cooling or rapid thawing or both? Cryo Letters. 2001;22:157–62.

Jones A, Van Blerkom J, Davis P, Toledo AA. Cryopreservation of metaphase II human oocytes effects mitochondrial membrane potential: implications for developmental competence. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:1861–6.

Kuleshova LL, Lopata A. Vitrification can be more favorable than slow cooling. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:449–54.

Kuleshova L, Gianaroli L, Magli C, Ferraretti A, Trounson A. Birth following vitrification of a small number of human oocytes: case report. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:3077–9.

Lane M, Gardner DK. Differential regulation of mouse embryo development and viability by amino acids. J Reprod Fertil. 1997;109:153–64.

Lane M, Gardner DK. Vitrification of mouse oocytes using a nylon loop. Mol Reprod Dev. 2001;58:342–7.

Lane MW, Ahern TJ, Lewis IM, Gardner DK, Peura TT. Cryopreservation and direct transfer of in vitro produced bovine embryos: a comparison between vitrification and slow-freezing. Theriogenology. 1998;49:170.

Lane M, Bavister BD, Lyons EA, Forest KT. Containerless vitrification of mammalian oocytes and embryos. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:1234–6.

Leese HJ, Conaghan J, Martin KL, Hardy K. Early human embryo metabolism. Bioessays. 1993;15:259–64.

Li JJ, Pei Y, Zhou GB, Suo L, Wang YP, Wu GQ, et al. Histone deacetyltransferase1 expression in mouse oocyte and their in vitro-fertilized embryo: effect of oocyte vitrification. Cryo Letters. 2011;32:13–20.

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8.

Lucena E, Bernal DP, Lucena C, Rojas A, Moran A, Lucena A. Successful ongoing pregnancies after vitrification of oocytes. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:108–11.

Manipalviratn S, Tong ZB, Stegmann B, Widra E, Carter J, DeCherney A. Effect of vitrification and thawing on human oocyte ATP concentration. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:1839–41.

Mavrides A, Morroll D. Cryopreservation of bovine oocytes: is cryoloop vitrification the future to preserving the female gamete? Reprod Nutr Dev. 2002;42:73–80.

Mitchell M, Schulz SL, Armstrong DT, Lane M. Metabolic and mitochondrial dysfunction in early mouse embryos following maternal dietary protein intervention. Biol Reprod. 2009;80:622–30.

Monzo C, Haouzi D, Roman K, Assou S, Dechaud H, Hamamah S. Slow freezing and vitrification differentially modify the gene expression profile of human metaphase II oocytes. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:2160–8.

Mullen SF, Agca Y, Broermann DC, Jenkins CL, Johnson CA, Critser JK. The effect of osmotic stress on the metaphase II spindle of human oocytes, and the relevance to cryopreservation. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:1148–54.

Needleman DJ, Ojeda-Lopez MA, Raviv U, Ewert K, Jones JB, Miller HP, et al. Synchrotron X-ray diffraction study of microtubules buckling and bundling under osmotic stress: a probe of interprotofilament interactions. Phys Rev Lett. 2004;93:198104.

NIH Guide. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. Bethesda: Institute for Laboratory Animal Research (ILAR) of the National Academy of Science; 1996.

Pantaleon M, Harvey MB, Pascoe WS, James DE, Kaye PL. Glucose transporter GLUT3: ontogeny, targeting, and role in the mouse blastocyst. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3795–800.

Pickering SJ, Johnson MH. The influence of cooling on the organization of the meiotic spindle of the mouse oocyte. Hum Reprod. 1987;2:207–16.

Pickering SJ, Braude PR, Johnson MH, Cant A, Currie J. Transient cooling to room temperature can cause irreversible disruption of the meiotic spindle in the human oocyte. Fertil Steril. 1990;54:102–8.

Porcu E. Textbook of assisted reproductive techniques laboratory and clinical perspectives. In: Gardner D, Weissman A, Howles C, Shoham Z, editors. Oocyte cryopreservation. United Kingdom: Martin Dunitz Ltd; 2001. p. 233–42.

Quintans CJ, Donaldson MJ, Bertolino MV, Pasqualini RS. Birth of two babies using oocytes that were cryopreserved in a choline-based freezing medium. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:3149–52.

Rall WF, Fahy GM. Ice-free cryopreservation of mouse embryos at −196 degrees C by vitrification. Nature. 1985;313:573–5.

Reers M, Smith TW, Chen LB. J-aggregate formation of a carbocyanine as a quantitative fluorescent indicator of membrane potential. Biochemistry. 1991;30:4480–6.

Reubinoff BE, Pera MF, Vajta G, Trounson AO. Effective cryopreservation of human embryonic stem cells by the open pulled straw vitrification method. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:2187–94.

Rho GJ, Kim S, Yoo JG, Balasubramanian S, Lee HJ, Choe SY. Microtubulin configuration and mitochondrial distribution after ultra-rapid cooling of bovine oocytes. Mol Reprod Dev. 2002;63:464–70.

Richards T, Wang F, Liu L, Baltz JM. Rescue of postcompaction-stage mouse embryo development from hypertonicity by amino acid transporter substrates that may function as organic osmolytes. Biol Reprod. 2010;82:769–77.

Rienzi L, Romano S, Albricci L, Maggiulli R, Capalbo A, Baroni E, et al. Embryo development of fresh ’versus‘ vitrified metaphase II oocytes after ICSI: a prospective randomized sibling-oocyte study. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:66–73.

Rubi B, del Arco A, Bartley C, Satrustegui J, Maechler P. The malate-aspartate NADH shuttle member Aralar1 determines glucose metabolic fate, mitochondrial activity, and insulin secretion in beta cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:55659–66.

Saheki T, Kobayashi K, et al. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of citrin (a mitochondrial aspartate glutamate carrier) deficiency. Metab Brain Dis. 2002;17:335–46.

Selman H, Angelini A, Barnocchi N, Brusco GF, Pacchiarotti A, Aragona C. Ongoing pregnancies after vitrification of human oocytes using a combined solution of ethylene glycol and dimethyl sulfoxide. Fertil Steril 2006.

Stachecki JJ, Cohen J, Willadsen S. Detrimental effects of sodium during mouse oocyte cryopreservation. Biol Reprod. 1998;59:395–400.

Stachecki JJ, Cohen J, Willadsen SM. Cryopreservation of unfertilized mouse oocytes: the effect of replacing sodium with choline in the freezing medium. Cryobiology. 1998;37:346–54.

Stachecki JJ, Cohen J, Schimmel T, Willadsen SM. Fetal development of mouse oocytes and zygotes cryopreserved in a nonconventional freezing medium. Cryobiology. 2002;44:5–13.

Steeves CL, Hammer MA, Walker GB, Rae D, Stewart NA, Baltz JM. The glycine neurotransmitter transporter GLYT1 is an organic osmolyte transporter regulating cell volume in cleavage-stage embryos. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13982–7.

Vajta G, Nagy ZP. Are programmable freezers still needed in the embryo laboratory? Review on vitrification. Reprod Biomed Online. 2006;12:779–96.

Van Blerkom J. Mitochondria in human oogenesis and preimplantation embryogenesis: engines of metabolism, ionic regulation and developmental competence. Reproduction. 2004;128:269–80.

Van Blerkom J, Davis P. High-polarized (Delta Psi m(HIGH)) mitochondria are spatially polarized in human oocytes and early embryos in stable subplasmalemmal domains: developmental significance and the concept of vanguard mitochondria. Reprod Biomed Online. 2006;13:246–54.

Van Blerkom J, Davis P, Mathwig V, Alexander S. Domains of high-polarized and low-polarized mitochondria may occur in mouse and human oocytes and early embryos. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:393–406.

Van Blerkom J, Davis P, Alexander S. Inner mitochondrial membrane potential (DeltaPsim), cytoplasmic ATP content and free Ca2+ levels in metaphase II mouse oocytes. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:2429–40.

Van Winkle LJ, Haghighat N, Campione AL. Glycine protects preimplantation mouse conceptuses from a detrimental effect on development of the inorganic ions in oviductal fluid. J Exp Zool. 1990;253:215–9.

Vanhoutte L, Cortvrindt R, Nogueira D, Smitz J. Effects of chilling on structural aspects of early preantral mouse follicles. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:1041–8.

Yan J, Suzuki J, Yu X, Kan FW, Qiao J, Chian RC. Cryo-survival, fertilization and early embryonic development of vitrified oocytes derived from mice of different reproductive age. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2010;27:605–11.

Yoon TK, Kim TJ, Park SE, Hong SW, Ko JJ, Chung HM, et al. Live births after vitrification of oocytes in a stimulated in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer program. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:1323–6.

Zander DL, Thompson JG, Lane M. Perturbations in mouse embryo development and viability caused by ammonium are more severe after exposure at the cleavage stages. Biol Reprod. 2006;74:288–94.

Zhao XM, Du WH, Wang D, Hao HS, Liu Y, Qin T, et al. Recovery of mitochondrial function and endogenous antioxidant systems in vitrified bovine oocytes during extended in vitro culture. Mol Reprod Dev. 2011;78:942–50.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr. Karen Kind for her assistance with the gene expression experiments, Dr. Jeremy Thompson assistance with experimental design and David Froiland for his assistance with confocal microscopy. The authors acknowledge the support of the NHMRC and Channel 7 Children’s Research Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Capsule

The beneficial effects of glycine in oocyte vitrification solutions on mitochondrial homeostasis and blastocyst development.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zander-Fox, D., Cashman, K.S. & Lane, M. The presence of 1 mM glycine in vitrification solutions protects oocyte mitochondrial homeostasis and improves blastocyst development. J Assist Reprod Genet 30, 107–116 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-012-9898-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-012-9898-4