Abstract

Individuals with Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are prone to stress and anxiety affecting their mental health. Although developing coping and resilience are key to cope with stressors of life, limited research exists. We aimed to explore stakeholders’ experiences related to the coping and resilience of adults with ASD. We interviewed 22 participants, including 13 adults with ASD, five parents, and four service provides of adults with ASD from various Canadian provinces. Using thematic analysis, three themes emerged including: (a) societal expectations and conformity, (b) adjusting daily routines, and (c) learning overtime. This study highlights the importance of coping and informs the development of services to help enhance resilience among adults with ASD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a lifelong disorder characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and restrictive and repetitive patterns of behaviour (American Psychological Association, 2013). Although the core characteristics of ASD typically appear during childhood, most individuals with ASD continue to experience ASD-related challenges throughout the life including adulthood (Matson & Kozlowski, 2011; Whiteley et al., 2019). Concurrent mental health disorders are highly prevalent among individuals with ASD (Lai et al., 2019). It has been shown that adults with ASD are more likely to experience anxiety and stress related to coping with change and unpleasant events (Gillott & Standen, 2007). Despite the high prevalence of psychiatric conditions like anxiety and depression among adults with ASD, many adults with ASD and their families are not able to access appropriate mental health services, leading to negative outcomes including: significant distress, adaptive functioning impairments, challenges with independent living and poor quality of life (Maddox & Gaus, 2019). Lack of funding to access mental health services, long waitlists associated with mental health services, the fact that most supports are geared towards children with ASD rather than adults with ASD and mental health professionals’ limited knowledge of ASD were all found to be major barriers experienced by adults with ASD who attempted access mental health support (Camm-Crosbie et al., 2019). The finding that adults with ASD are especially prone to stress and mental health problems highlights the need to develop resources targeted at improving coping skills and resilience among adults with ASD (Bishop-Fitzpatrick et al., 2015).

Although there is no conceptual consensus regarding a definition of resilience (Halstead et al., 2018; Southwick et al., 2014), resilience has been defined by some authors as adapting positively in the face of adversity (Al-Jadiri et al., 2021). Resilience is dynamic and modifiable, and characterized by two criteria including, risks (adverse biological or environmental circumstances) and positive adaptations (competence and successful adjustment to life events) (Kaboski et al., 2017). Although resilience refers to the adaptive capacity, coping mechanisms refer to cognitive and behavioral efforts or strategies to manage taxing and stressful events (Dachez & Ndobo, 2018; Folkman & Moskowitz, 2004; Steinhardt & Dolbier, 2008). Previous studies have indicated a relationship between resilience and coping (Campbell-Sills et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2019). Several coping mechanisms have been already identified including problem-focused coping (where an individual aims to solve the problem that is causing stress) and emotion-focused coping (where an individual attempts to manage the negative emotions caused by the stressor and the search for new meaning to a stressful situation) (Dachez & Ndobo, 2018). A previous qualitative study found several coping strategies frequently employed by adults with ASD including, engaging in special interests, normalizing their view of ASD, seeking support from family and friends, and intellectualizing by ascribing meaning to particular events (Dachez & Ndobo, 2018). It has been found that inappropriate coping strategies such as avoidance and self-blame were linked to lower mental health-related quality of life in adults with ASD (Khanna et al., 2014). One possible consequence of maladaptive coping strategies is autistic burnout, which has been described as the chrsonic exhaustion and reduced tolerance to stimuli that results from the inability to cope with the chronic life stress (Raymaker et al., 2020). Constantly masking ASD symptoms and attempting to pass as an individual without an ASD can result in autistic burnout (Raymaker et al., 2020). There is a need to alleviate the use of maladaptive coping strategies and help gain necessary coping strategies in order to improve the health-related quality of life (Khanna et al., 2014).

Previous studies have indicated several models of resilience that make coping and adaptive responding more likely (Ledesma, 2014; Masten, 2001). This includes the compensatory model, which considers resilience as a tool to neutralizes exposures to risk factors, the challenge model that argues that exposure to risk factors can provides an opportunity to enhance resilience, and the protective factor model that posits there is an interaction between risk and the protective mechanisms in an individual (Ledesma, 2014; Masten, 2001; Ungar, 2019). Considering the theoretical framework of resilience, individual’s resilience can be determined based on how they can balance risk and protective factors (Ledesma, 2014; Masten, 2018; Ungar, 2019). Although the severity of disorder has been considered as a risk factor, a higher social support, family dynamics, socio-economic status, adaptation and positive thinking can help buffer the stress associated living with ASD (Al-Jadiri et al., 2021; Ghanouni & Hood, 2021; Bekhet et al., 2012).

While several publications have focused on resilience and coping strategies among family members of those with ASD, few studies have explored resilience and coping in individuals with ASD themselves (Dachez & Ndobo, 2018; Ghanouni & Hood, 2021; Khanna et al., 2014). A previous study has proposed a resilience framework by considering the importance of both risk and protective factors, when exploring why some individuals with ASD experience ongoing deficits related to functioning while others experience optimal outcomes (Kaboski et al., 2017). Both personality traits and environmental conditions should be considered, because they can either promote or impede adaption among individuals with ASD (Kaboski et al., 2017). Resilience frameworks stress the importance of considering the multitude of factors that can promote adaptation, including environmental variables and personality traits (Kaboski et al., 2017). Rather than simply focusing on how risk factors can result in negative outcomes, resilience frameworks also explore protective factors that can result in positive outcomes (Kaboski et al., 2017). Resilience frameworks view risk and protective factors as modifiable and at multiple levels to explore how these factors can influence ASD trajectories (Kaboski et al., 2017).

Overall, limited research has explored the direct experience of individuals with ASD related to resilience and coping strategies. Such scarcity in data prevents researchers and clinicians from understanding the barriers that currently impact adults with ASD and the coping mechanisms that adults with ASD use to circumvent the barriers they face. More research is critical, and should include the perspectives of adults with ASD to get a firsthand account of their experiences related to coping and resilience. Thus, the purpose of this project was to explore stakeholders’ experiences related to the coping and resilience of adults with ASD. This knowledge would be useful to provide insight regarding how individuals with ASD adapt to the stressors that they face, informing programs and services targeted at improving resilience and coping in adults with ASD.

Methods

Research Design

This study used a qualitative design approach to investigate lived experiences about coping and resilience among individuals with ASD. The primary research question was: What are the experiences of individuals with ASD related to resilience and coping mechanisms?

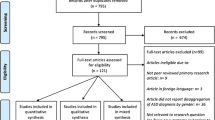

Participants

The research team used convenience sampling to recruit participants for this study. We recruited 22 participants from three groups of stakeholders, including: 13 adults with ASD (six females, seven males), five parents of adults with ASD (all female), and four service providers of adults with ASD (all female). To illustrate the geographic diversity, participants were recruited from various Canadian provinces including: three from Alberta, five from Prince Edward Island, two from Ontario, three from Quebec, one from British Columbia, three from Nova Scotia, three from Manitoba, two from New Brunswick. To recruit participants, posters were placed in public areas, clinics and community centres. Invitation letters were also circulated to invite individuals to participate in the study, Snowball sampling was used in this study, with participants being encouraged to share study information within their networks.

Individuals with ASD were included in this study if they met following eligibility criteria: a) they were aged 15 years or older, and b) they were diagnosed with ASD by a psychologist and the diagnosis was self-reported by participants. Service providers were also included in this study if they had at least one year of experience working with individuals who have ASD. Parents were eligible if they had an adult child with ASD. All participants were required to be able to communicate verbally in English in order to participate in this study.

The age of adults with ASD ranged between 27 and 53 years of age. Overall, six adults with ASD reported that they had at least one co-occurring condition. The self-reported co-occurring conditions were as followed: six adults with ASD indicated attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, three indicated a concurrent learning disability, and three stated a mental illness.

The age of parents of adults with ASD ranged between 46 and 63 years of age. Overall, four parents had reported their adult child having one or more co-occurring conditions. Altogether, one parent indicated their adult child had a co-occurring attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, one parent indicated that their adult child had a co-occurring learning disability, and two parents indicated that their adult child had a co-occurring mental health disorder. The age of their adult children with ASD ranged from 25 to 36 with an average age of 29.75 (SD = 4.57).

The age of service providers of adults with ASD ranged from 42 to 58 years of age. Their number of years of experience working as a service provider for adults with ASD ranged from 8 to 11 years, and the average years of experience working as an ASD service provider was 9.67 (SD = 1.52). There were two behavioural consultants, one day-program support provider, and one autism educational specialist. Please see Table 1 for more details.

Data Collection

Interested participants were asked to review the informed consent form with a member of the research team. Each participant needed to attend a 60-min interview session. Participants also completed an online questionnaire to collect demographic information such as: age, sex and their background. Interviews were scheduled at a convenient time and location for participants (face to face, over skype, or over the phone). An in-depth, semi-structured interview guide was used by members of the research team to explore coping mechanisms and resilience in individuals with ASD. Interview questions were developed by the research team and validated by two adults with ASD. We also received input from two service providers who were members of the autistic community to edit questions prior to use in the study. We piloted the interview to make sure questions are clear and easy to understand. Specific examples of questions were: What do individuals with ASD do when feeling stressed? What strategies will individuals with ASD use to improve resilience (overcome challenges)? What resources should be in place to promote the mental health and resilience of the those with ASD?

Interviews were recorded on a password-protected audio recorder. Field notes were also used by members of the research team to best capture participants’ responses. To maintain anonymity, names of participants were removed and participants were assigned pseudonyms. The Behavioural Research Ethics board approved this study.

Data Analysis

One research assistant transcribed all interviews verbatim, and another research assistant checked the transcripts to ensure accuracy and analyzed interview transcripts to decipher common themes. Transcripts were read by two members of the research team and were analyzed using Nvivo software. Researchers used constant comparative methods to develop codes, create categories, and identify overarching themes. Two research assistants worked independently to code data and then came together to develop categories and themes based on the common patterns in data. Any disagreement between the two coders was resolved via a consensus meeting with the rest of the team to discuss differences in their findings to reach agreement.

Researchers engaged in reflexivity when coding interviews by using memos and reflecting on their biases and assumptions. Triangulation was also used to ensure that the study findings were credible and that the perspectives and ideas of multiple researchers were incorporated.

Results

Participants discussed the contexts in which adults with ASD can develop resilience and suggested that various coping strategies are used to help adults with ASD. Three areas related to resilience and coping strategies for adults with ASD were identified including: (1) societal expectations and conformity, (2) adjusting daily routines, and (3) learning over time.

Societal Expectations and Conformity

Participants shared their experiences and pressure felt related to conforming to societal expectations. Three concepts were generated from this theme: (a) societal attitudes towards adults with ASD, (b) inaccurate generalisation of abilities, and (c) the need for inclusion and graded expectations.

Societal Attitudes Towards Adults with ASD

Participants discussed how adults with ASD were often the target of biases and negative attitudes. Participants noted that society often holds negative perceptions of adults with ASD. For instance, Tara (an adult with ASD), stated:

“Sometimes people just make assumptions, like they think that you're being rude. Or maybe they think you are being lazy something, but you are not. And they don't understand. They don't understand you, and that makes it really hard.”

From Tara’s experiences, members of society sometimes fail to understand why people with ASD act the way that they do and hold negative assumptions about adults with ASD. Similarly, Suzy (an adult with ASD) said, “autistic people feel like they're bad people because they never knew they were autistic and society taught them they were bad”. This suggests the inherent role of societal perception on how ASD symptoms may be attributed. Sacha, a service provider for adults with ASD also stated:

“I think there is a really strong role for the rest of society to stop being so judgmental. So, as an example we have our young man [with ASD] who loves music, when he dances he really looks unusually, right you know? I've had people in the community say, ‘Maria you have to stop him from doing that in public’. And it’s because he looks different and when we look different, we live in an unsafe society and we are vulnerable when were different.”

This statement showcases how adults with ASD may be judged for expressing themselves in unconventional ways and how this can result in them feeling unsafe. Jack (an adult with ASD) also said:

“People in the community gotta understand that you know we’re not great at being sociable, or eye contact or anything like that, [so] we can come off as kinda rude but we don't mean to be, … So, they meet us and they go, ‘Well' you know, they don't know what to make of us.”

This illustrates how others within society may negatively misinterpret the behaviors associated with ASD without acknowledging what led to these behaviours.

Inaccurate Generalization of Abilities

Participants indicated that adults with ASD were often subjected to inaccurate assumptions based on their abilities. Participants suggested that individuals within society often falsely assume that adults with ASD who experience a few specific deficits, may function poorly in all areas. For example, Sophy (an adult with ASD), stated:

“Nobody in autism is fully high functioning in all areas. So, there are low functioning areas, and there are high functioning areas. And I think a lot of people don't understand what that means. But you can be very high- you can be very intelligent, but there’s certain areas you have... you're low functioning. So that understanding is important to communicate to people.”

In stating that a person’s level of functioning in one area does not necessarily correlate with their functioning in other areas, Sophy suggests that generalizations about the capabilities of adults with ASD are prevalent within society. Sophy elaborated on this idea by saying: “There are people like me that are high functioning, so it doesn't appear on the surface that there’s anything the matter. But the truth is that there is something the matter.” Similarly, Tara (an adult with ASD) stated:

“It’s like people want you to have a certain level of communication um, to be able to function at a higher level and they don't understand that its different. Some people can't function that way, and it just gets hard.”

These quotes show how adults with ASD may face difficulties when they to do not function the way that members of society believe they should.

The Need for Inclusion and Graded Expectations

Participants stressed the need for society to acknowledge and accept neurodiversity of individuals with ASD. For instance, Suzy (an adult with ASD) said:

“Our sense of belonging is incredibly important but it’s often we, we need more of community and like, just we never have a sense of belonging the neuro-typical society in general you know, and it can be made less painful defiantly but educating [informing] neuro-typical about us, it’s not 'we're broken' we just are different.”

In saying this, Suzy implies that how information sharing is necessary to combat the medical model of disability to fix problems. She also stressed the importance of fellowship and belonging for adults with ASD and the need for society become more accepting of neurodiverse individuals. Sebastian (an adult with ASD), described the difficulties he faced as an adult with ASD having to conform to neurotypical societal expectations when he said, “that’s been a big realization the pressure that society puts on people to conform, really hurts those of us who are neuro-divergent because it disables us in so many ways”. He also added:

“I have to deal with the realities and I have to accept that I'm never going to be a neuro-typical person and it's okay that I can't do things the way that neuro-typical people do them. And that means living my life differently.”

This statement showcases experiences of an adult with ASD to adjust his lifestyle. Similarly, other stakeholders indicated that adults with ASD feel pressured in conforming to societal expectations related to independent living. For example, Milo (an adult with ASD), described his experience and highlighted how he has to explain that he is unemployed. He said:

“You know not having a career, having to answer, to answer people, 'Well, what do you do?' Well they ask you, 'What are you doing', the weird, the difficult normal question that anybody asks in a social setting and that’s totally fair but then, you know you're inquiring and you're required to answer well 'what do you do as a career' and you don't have one.”

This indicates that adults with ASD may worry about how they are perceived by others when describing their stage in life and struggle to explain why they have not met societal expectations associated with their age. To cope with these societal expectations, participants noted that it is important for adults with ASD set reasonable expectations and goals. For instance, William (an adult with ASD) said:

“I think another thing is expectations, it thinks it’s probably a good thing to have a graded expectation for people with disabilities. But the system just puts everything on you, that’s the whole independence thing is like, oh, and that’s engrained in our society. You become 18, you become independent supposedly, and nobody can help you.”

These quotes show how society’s expectation of norms can affect feeling of inclusion among adults with ASD and how they view and experience these situations.

Adjusting Daily Routines

Participants suggested that adults with ASD adapt their daily routines as a coping strategy and to develop resilience. Three concepts emerged under this theme including: (a) engaging in recreation and leisure, (b) seeking emotional support, and (c) adopting technology to adjust routines.

Engaging in Recreation and Leisure

Participants suggested that adults with ASD adjust their daily routines by taking time to engage in recreation and leisure pursuits. For example, Drake (an adult with ASD), emphasized the importance of incorporating breaks into his daily schedule, when he said, “I guess, just focus a bit more, take a break at times, and then get back on this”. In saying this, David acknowledges how taking breaks can help him recuperate and refocus. Similarly, Madison (a parent of an adult with ASD), stated:

“What makes him [my son with ASD] happy is participating and horseback riding. He loves horses, he loves animals. He loves archery…. So, those types of activities we foster those for him, and make sure that he's participating in that kind of stuff.”

In stating this, Madison recognizes how necessary it is to ensure that her son engages in these meaningful activities on a regular basis. Participants also emphasized how incorporating leisure into their daily routine was important and helped them with soothing and coping with stress. For instance, Cameron (an adult with ASD) stated that: “I'd recommend [everyone], if they could like find their own way of like calming themselves. Kinda like listen to music, watch a TV show, read, write, cause it really helps.” Similarly, Kalie (an adult with ASD) said:

“One thing that helps me is doing an activity that I enjoy whenever I'm feeling over-whelmed by my emotions. Like, for example I like to listen to music. And that usually works quiet well for me. I also like to play video games, whether it was on the computer or it’s on a console, or hand held. And those can also be quite helpful.”

In saying this, Kalie acknowledges how participating in leisure activities such as listening to music or playing videogames is beneficial in coping with distressing emotions like feeling overwhelmed. Kalie also explains how taking baths has been effective in helping her cope with, when she says, “I've been told that lying in the bath, with bath soap helps. So, I just try to leave the situation and just relax for a bit before going back in.” Thus, incorporating recreation and leisure breaks into the daily schedule of adults with ASD can bring joy and serve as a coping strategy.

Seeking Emotional Support

Participants identified seeking social support as a way that adults with ASD adjust their daily routines. For instance, Suzy (an adult with ASD) acknowledged the positive impact that joining a support group for adults with ASD had on her life, when she stated:

“I joined an ASD support group, that for the first time in my life I had a group of people around me that were as weird ones too [like myself], and I was like 'wow this is amazing, I love it, you know? And ever since then I have attended that support group whenever my job permits me.”

In making this statement, Suzy showcases the effect of attending a support group and integrating social participation into her daily routine. Madison (a parent of an adult with ASD), stated her belief that social support would help her son thrive when she says, “My goal is just for Alex [my son with ASD] to be able to socialize more, and just break out of his shell”. Although socialization may help, not everyone knows how to do it. Jack (an adult with ASD), states, “I'd like to learn how to [socialize], I don't know how get and keep a friend maybe”. This statement also indicates the importance of friendships and social support for adults with ASD.

Adopting Technology to Adjust Routines

Making use of technology and other supports is another way in which participants suggested that adults with ASD adjust their daily routines. The use of technology to make socialization easier was particularly evident in interviews. For instance, Tara (an adult with ASD) stated, “I've heard from a lot of other people on the spectrum that if they have a really hard time making friends in life, they can make friends easier on the internet and that really helps them.” Likewise, Lily (an adult with ASD) explains how the use of technology can enable individuals to socialize:

“Find other autistic people online, because I haven't found like any really in person, yeah. Find other people through like social media stuff who you feel a connection with, so that you don't feel like you’re in it completely by yourself.”

This showcases how the use of technology to interact with others is the key aspect of the daily routine of adults with ASD.

In addition to using technology to socialize, adults with ASD also suggested the use of technology to achieve their activities of daily living. Tara (an adult with ASD), stated:

“Before it’s [daily routines were] used to be a really big problem, because I just wouldn't get groceries and stuff, and I didn't have anyone to help me but. Now, some stores deliver groceries. So, I order my groceries and they deliver them, and that really, helps me a lot.”

Tara’s statement exemplifies how technology has been useful in her responsibility of grocery shopping. In a similar way, Nora (an adult with ASD) explains that the reminder function on her phone helps her to complete her daily activities when she says, “Because there’s an app for whatever I needed to be reminded for, so it's… a huge strategy.” William, an adult with ASD, also stated that he makes use of a similar phone application when he says, “There’s an app, where you put tasks in and it will tell you when to do them.” These statements demonstrate how adults with ASD may incorporate technology into their routines as a strategy to accomplish their activities of daily living.

Learning Over Time

Participants suggested that adults with ASD can learn how to develop resilience and coping strategies over time. Within the theme of learning over time, three concepts were identified including: (a) recognising strengths and weaknesses, (b) education and advocacy, and (c) and processing traumatic experiences.

Recognising Strengths and Weaknesses

Participants indicated that adults with ASD cope and develop resilience by gradually learning to identify their strengths and shortcomings. The need to recognize the strengths can be seen when Sophy (an adult with ASD), stated:

“I believe that every child for example, has gifts and talents, and to take the time for parents or teachers to find what are those gifts and talents, and then develop those gifts and talents.”

In saying this, Sophy stressed the need to acknowledge the unique capabilities of individuals with adult and to develop and maximize these strengths. Similarly, Dawn (a service provider for adults with ASD) stated:

“I also think that there needs to be that acknowledgement, or that, you know, support of the individual to help them to understand what their strengths and their challenges are.”

This showcases how acknowledging and cultivating the strengths of adults with ASD can help with the development of resilience.

Participants also stressed the importance of recognizing the deficits or challenges of adults with ASD. For instance, Nora (an adult with ASD) stated,

“If you don't, if you’re not able to address and talk about the weakest points, the things you really struggle with the most, everything else is only going to be a show, …, a chain is only as strong as its weakest link, so, resilience to me is actually strengthening that weakest link in your own psychology.”

This indicates how resilience involves identifying and working on weaknesses to improve mental health. Similarly, Holly (a parent of an adult with ASD), stressed the importance of acknowledging the triggers of individuals with ASD over time when she said:

“When it comes to autism, because every person is different, the more they can explain about themselves and, learn their own triggers, they need to take responsibility for their own actions but also be, you know accepting and um, helping others understand.”

This statement showcases how it is necessary for individuals with ASD to understand their triggers, hold themselves accountable for their actions and help others understand what their triggers are. Stakeholders also highlighted how it is important for adults with ASD to embrace their identity. For instance, Milo an adult with ASD stated:

“I'm on the spectrum, and I have lived like that for a ‘long time’. I've relied on these identities to describe who I was or, you know that existential question. I wouldn't be able to tell you, I would just say that I'm autistic. And obviously there is a lot more to who I am [with strengths and capabilities] then those identities.”

This statement demonstrates how Milo has come to acknowledge his identify as an individual with ASD, but also has learned that his diagnosis of ASD is only one aspect of what makes him who he is. These quotes illustrate that recognizing and managing strengths and weaknesses among individuals with ASD may be essential in cultivating resilience over time.

Education and Advocacy

Education and advocacy were also identified by participants as important coping strategies and mechanisms of developing resilience. For instance, Holly (a parent of an adult with ASD) stated:

“One of the things that I think is so very important is the education piece for the individuals [with ASD], making sure that individuals know all they need to know about their own disability. Because once they are very aware about what works for them and what doesn't work, [they can] become that advocate and speak up for themselves.”

In saying this, Holly, recognized how education can help individuals become more comfortable with their diagnosis and understand ways to manage their ASD. Another adult with ASD, Sebastian, stated: “We need better education for autism, for the general public, we need better education for doctors, we need better systems.”

Participants also emphasized how advocacy and supportive community can facilitate coping. For instance, Kalie (an adult with ASD) stated:

“Having a strong community of people and nurturing supports at a young age or just having people around you that care, …., having a strong independent, a strong support system at a young age, I think is very important in creating a mind that is confident to promote self-advocacy.”

This statement shows how, in Kalie’s experience, having a supportive community network has been key to helping adults to advocate for themselves and their needs.

Processing Traumatic Experiences

Participants also expressed how trauma affects the ability of adults with ASD to cope, thrive and develop of resilience. Several participants reflected on how their past negative experiences continue to affect them. For instance, Kalie (an adult with ASD) explained how she is afraid to learn to drive after being involved in a motor vehicle accident when she said,

“I'm actually afraid of getting my own transportation. I've been a passenger in a vehicle that was in an accident at least once, and although I wasn’t hurt physically, sometimes, they make me nervous or they shake me up. I'm just too afraid to learn to drive.”

This statement showcases how one traumatic event had a long-lasting impact on Kalie’s life and discouraged her from learning to drive. Suzy, another adult with ASD, described the impact that being bullied within the workplace and at school had on her when stating: “I was always the outcast and bullied and viewed as the weird one.” In saying this, Suzy described the how the bullying she encountered throughout her life affected her. Participants also described how their encounters with other individuals have resulted in trauma. For instance, Lucy (an adult with ASD) described the impact that a past abusive relationship had on her when she said:

“This was while I was in the middle of breaking up with my partner. Because he was not supportive at all, he did not believe the diagnosis, he didn't think that I was on the spectrum, he didn't think that he had to treat me any differently. So, as I get older, I find that I have very, my tolerance of, of rude behavior, I'm conditioned to deal with rude behavior.”

Lucy’s statement provides insight into how unsupportive relationships can result in long-lasting trauma and how to enhance tolerance over time to cope with trauma. Participants also suggested using mental health counselling services to manage trauma. For instance, Nora (an adult with ASD), stated: “So, trauma counselling, trying to come grips with a lifetime of trauma. That is a huge, huge, area, that you need address.” Similarly, Nora (an adult with ASD) stated:

“Resilience only comes when you can address the most hurtful part in you, and then there’s a space where you can actually talk about it, and that space can be held.”

These statements highlight the importance of processing trauma over time with counselling services as a strategy to enhance coping and resilience.

Discussion

Through interviews with adults with ASD, their parents, and service providers, this study explored the experiences of coping and resilience among individuals with ASD. We found that adapting to societal expectations and pressures to conform, adjusting their daily routines, and learning overtime are several factors to affect the development of coping and resilience.

Participants stated that adults with ASD may face negative attitudes from members of society as a result of their ASD diagnosis. Individuals with ASD may be viewed to be different and stereotypical, which may contribute to individuals’ low self-esteem (Maich, 2014; Treweek et al., 2019). It has been found that adults with ASD may feel pressured to fit into neurotypical society, leading to increased stress and anxiety among them and their families (Rosqvist, 2012). While participants in the current study did not indicate potential discrimination, research shows that implicit bias towards adults with ASD may lead to mental health challenges (Dickter et al., 2020). Participants in the present study highlighted that the members of society may misinterpret behaviours and/or make inaccurate generalizations about the abilities of adults with ASD. This finding may be explained by the public lack of knowledge about ASD heterogeneity and its associated behaviors (Draaisma, 2009; Martin et al., 2013). Despite research showing that individuals with ASD may present vast differences in their impairment levels (Masi et al., 2017), participants in the present study indicated that members of society assume that every adult with ASD experiences the same level of deficits. Education, awareness and discourses about ASD may be helpful to improve societal perception about individuals diagnosed with ASD in community (Alsehemi et al., 2017).

As a novel finding, participants highlighted the importance of social inclusion and belonging in developing resilience and coping. Participants emphasized that society needs to accept the neurodiversity and differences in behaviors of adults with ASD. This is consistent with the social model of disability, which suggests that barriers within society, not individuals’ differences, make them feel disabled (Oliver, 2013). The social model of disability recognizes the unique characteristics of individuals with disabilities, rather than expecting them to conform to able-bodied, neurotypical norms (French & Swain, 2013). Research suggests that the social model of disability can be applicable to individuals with ASD by promoting the use of positive language about ASD, developing support services, and enacting policies to ensure the rights of adults with ASD are respected (Woods, 2017). This is aligned with the social-ecological model of resilience, which emphasizes social contexts that make adaptive responding more likely (Ungar et al., 2013). According to the social-ecological model of resilience, factors at the individual, interpersonal, community, organizational, and societal levels should be considered to facilitate health promotion (CDC, 2021; Ungar, 2015; Ungar et al., 2013). Stakeholders in the project stressed the need to have graded expectations for adults with ASD, recognizing that their life milestones and when they are reached may be different compared to their neurotypical peers. No known research has explored the need for graded expectations for adults with ASD to enhance inclusion but findings from this study suggest that graded expectations may be beneficial coping strategy to help accept differences and enhance inclusion.

Participants also stressed the importance of adjusting their daily routines by incorporating recreational activities and leisure to cope with the stressors of life. Given the perceived high levels of stress among individuals with ASD and their families, participations in leisure activities has been found to be an effective stress survivals strategy to reduce and manage stress, helping to facilitate the development of resilience (Denovan & Macaskill, 2017; García-Villamisar & Dattilo, 2010; Iwasaki et al., 2010; Stacey et al., 2018). Relaxation techniques and meditation exercises can help individuals with ASD enhance self-control and avoid burnout (Raymaker et al., 2020; Siqueira & Ahmed, 2012). Although participants in the current study did not explicitly state how to deal with potential burnout, it has been found that taking regular breaks can allow adults with ASD to cope with sensory overloads and the stressors of everyday life (Higgins et al., 2021; Marcus, 1984; Raymaker et al., 2020). Regular socialization and seeking social support throughout the day was also an important coping strategy for participants. It has been shown that social support is a protective factor against depressive symptoms and mental health challenges in adults with ASD (Hedley et al., 2017). Previous research has also indicated that social support is significantly tied to the quality of life for adolescents with developmental disabilities and can help promote resilience (Migerode et al., 2012).

Participants in the present study emphasized how incorporating technology into their daily routines enabled them to cope with stressors and manage their daily tasks. It has been found that checklist apps and alarms were effective in helping individuals to plan and organize their days and support their executive functioning (Desideri et al., 2020). Our participants also indicated that they used technology for social support and networking, which is consistent with pervious research (Cafiero, 2012; Mazurek, 2013). Given the profound interest of individuals with ASD to adopt technology and the fast growth of technologies in the recent years (Diener et al., 2015; Mazurek, 2013), incorporating appropriate technology into daily routines can be an effective coping strategy for adults with ASD.

Participants suggested that acknowledging their disability and self-acceptance of ASD identity may be a beneficial coping strategy. It has been shown that acceptance of autistic identity is a protective factor against mental health issues for adults with ASD (Cage et al., 2018). Our stakeholders stressed how recognising their strengths and weaknesses was important in the process of coping and developing resilience. It has been shown that well-developed identity can comprise of understanding individuals’ uniqueness and limitations (Cresswell & Cage, 2019). Identity formation for individuals with developmental disabilities is a dynamic process that involves accepting the ASD label and assimilating the meaning of their disability into their personal and social identity (Goff & Springer, 2017). A key step in identity formation for individuals with disabilities involves embracing disability narratives and acknowledging their unique experiences (Goff & Springer, 2017). Given that self-advocacy is important in the process of identity formation (Leadbitter et al., 2021), individuals with disability should know themselves, their rights, and how to negotiate their desired goals (Test et al., 2005).

Our participants stated that they experienced emotional trauma throughout their lives, but they learned how to process them to enhance resilience. Several research studies have found that adverse childhood experiences are common among individuals with ASD (Hoover & Kaufman, 2018; Morrow Kerns et al., 2017). For instance, research has shown that adults with ASD are at an increased risk of adverse childhood experiences including parental divorce and bullying and that these experiences can negatively affect physical and mental health (Hoover & Kaufman, 2018; Morrow Kerns et al., 2017). Consistent with the findings of these studies, participants in the present study reflected on the lasting impact that traumatic experiences have on their mental health. Although personal traits affect how an individual can respond to a traumatic event, some research has found that it is possible to teach resilience and coping to children with disabilities by promoting them to connect with others and helping them to feel control over their lives (Mather & Ofiesh, 2005). As both adults and children can greatly benefit from learning to be resilient to bounce back from setbacks, efforts to teach resilience to individuals can start in childhood, leading to more resilient adults (Gartrell & Burger Caroine, 2014). Teaching resilience and coping can help adults with ASD use them, when need be, though there is limited research on how we can facilitate the learning process. Given the importance of resilience to overcome challenges and cope with adversity, there is a need for support services to help adults with ASD manage traumatic events and learn resilience (Bonanno, 2005; Kimhi & Eshel, 2015).

Overall, resilience has been considered as one of the primary elements within the mental health promotion framework. Given the lifelong nature of ASD, resilience can allow individuals to tap into their strengths and support services to overcome potential challenges. This is much more pronounced in the contexts of additional environmental stressors, such as the context of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) (Masten & Motti-Stefanidi, 2020). The worldwide outbreak of COVID-19 could be a source of unexpected stress and adversity for many people, especially those who experience health disparities including ASD. Findings from this study can inform how to promote resilience and coping among adults with ASD, reduce the effects of stressful events, and most importantly prevent future mental health.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are several limitations of the study. The first limitation of this study is the small sample size from each stakeholder, which may affect the representation of overall populations. Furthermore, this study only included middle-aged adults with ASD, so the findings from this study may not be generalizable to children or older adults with ASD. A second limitation of this study is that it only included adults with ASD, who were able to communicate verbally, and did not make use of alternative communication to include the perspectives of adults with ASD who cannot communicate verbally. A third limitation of this study is that it was cross-sectional in nature, so it could not capture how coping strategies may change over the life course. Furthermore, due to the exploratory nature of this qualitative study, it is limited to portray comprehensive information about risk and protective factors among adults with ASD. Finally, this project is limited to indicate how race/ethnicity and gender identity can influence coping and resilience.

It is suggested that future studies recruit a larger sample size from each stakeholder group to better represent diversity in race/ethnicity, gender identity, and socio-economic status and to explore how/to what extent these risk and protective factors can affect coping. It is also recommended to explore the viewpoints of sub-populations with ASD who experience communication deficits using alternate modes of communication. Additionally, longitudinal research that involves follow-up interviews is needed to explore how the coping skills and resilience of adults with ASD may change overtime. It is also suggested to explore family support or resources that adults with ASD access to cope with traumatic experiences and the resources that adults with ASD wish they had to access to enhance their coping and resiliency.

Conclusion

The findings from this study add to the limited research on coping and resilience for adults with ASD by illuminating stakeholder perspectives. While most of the exiting literature has focused on family members of children with ASD and childhood outcomes, this study focuses on the experience of adults with ASD related to coping skills and resilience. This study provides new insight into how adults with ASD may advance resilience and coping over time, informing future efforts to advance services to promote resilience.

References

Al-Jadiri, A., Tybor, D. J., Mulé, C., & Sakai, C. (2021). Factors associated with resilience in families of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 42(1), 16–22. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000867

Alsehemi, M. A., Abousaadah, M. M., Sairafi, R. A., & Jan, M. M. (2017). Public awareness of autism spectrum disorder. Neurosciences, 22(3), 213–215.

Bishop-Fitzpatrick, L., Mazefsky, C. A., Minshew, N. J., & Eack, S. M. (2015). The relationship between stress and social functioning in adults with autism spectrum disorder and without intellectual disability: Stress and social functioning in adults with autism. Autism Research, 8(2), 164–173. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1433

Bonanno, G. A. (2005). Resilience in the face of potential trauma. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(3), 135–138. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00347.x

Cafiero, J. M. (2012). Technology supports for individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Special Education Technology, 27(1), 64–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/016264341202700106

Cage, E., Di Monaco, J., & Newell, V. (2018). Experiences of autism acceptance and mental health in autistic adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(2), 473–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3342-7

Camm-Crosbie, L., Bradley, L., Shaw, R., Baron-Cohen, S., & Cassidy, S. (2019). ‘People like me don’t get support’: Autistic adults’ experiences of support and treatment for mental health difficulties, self-injury and suicidality. Autism, 23(6), 1431–1441. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318816053

Campbell-Sills, L., Cohan, S., & Stein, M. (2006). Relationship of resilience to personality, coping, and psychiatric symptoms in young adults. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(4), 585–599.

CDC, (2021). The Social-Ecological Model: A Framework for Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/about/social-ecologicalmodel.html.

Chen, H., Xu, J., Mao, Y., Sun, L., Sun, Y., & Zhou, Y. (2019). Positive coping and resilience as mediators between negative symptoms and disability among patients with schizophrenia. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 641.

Cresswell, L., & Cage, E. (2019). ‘Who Am I?’: An exploratory study of the relationships between identity, acculturation and mental health in autistic adolescents. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(7), 2901–2912.

Cuzzocrea, F., Murdaca, A. M., Costa, S., Filippello, P., & Larcan, R. (2015). Parental stress, coping strategies and social support in families of children with a disability. Child Care in Practice, 22(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2015.1064357

Dachez, J., & Ndobo, A. (2018). Coping strategies of adults with high-functioning autism: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Adult Development, 25(2), 86–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-017-9278-5

Denovan, A., & Macaskill, A. (2017). Building resilience to stress through leisure activities: A qualitative analysis. Annals of Leisure Research, 20(4), 446–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2016.1211943

Desideri, L., Di Santantonio, A., Varrucciu, N., Bonsi, I., & Di Sarro, R. (2020). Assistive technology for cognition to support executive functions in autism: A scoping review. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 4(4), 330–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41252-020-00163-w

Dickter, C. L., Burk, J. A., Zeman, J. L., & Taylor, S. C. (2020). Implicit and explicit attitudes toward autistic adults. Autism in Adulthood, 2(2), 144–151. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2019.0023

Diener, M. L., Wright, C. A., Wright, S. D., & Anderson, L. L. (2015). Tapping into technical talent: Using technology to facilitate personal, social, and vocational skills in youth with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). In T. A. Cardon (Ed.), Technology and the Treatment of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (pp. 97–112). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Draaisma, D. (2009). Stereotypes of autism. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1522), 1475–1480. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2008.0324

Folkman, S., & Moskowitz, J. (2004). Coping: Pitfalls and promise. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(1), 745–774.

French, S., & Swain, J. (2013). Changing relationships for promoting health. In Tidy’s Physiotherapy (pp. 183–205). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7020-4344-4.00010-9

García-Villamisar, D. A., & Dattilo, J. (2010). Effects of a leisure programme on quality of life and stress of individuals with ASD: Effects of a leisure programme. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 54(7), 611–619. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01289.x

Gartrell, D., & Burger Caroine, K. (2014). Fostering resilience: Teaching socio-emotional skills. YC Young Children, 69(3), 92–93.

Gerhardt, P. F., & Lainer, I. (2010). Addressing the needs of adolescents and adults with autism: A crisis on the horizon. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 41(1), 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-010-9160-2

Ghanouni, P., & Hood, G. (2021). Stress, coping, and resiliency among families of individuals with autism: A systematic review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorder, 8, 389–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-021-00245-y

Gillott, A., & Standen, P. J. (2007). Levels of anxiety and sources of stress in adults with autism. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 11(4), 359–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629507083585

Goff, B. S., & Springer, N. P. (Eds.). (2017). Intellectual and developmental disabilities: A roadmap for families and professionals (1st ed.). Routledge.

Halstead, E., Ekas, N., Hastings, R. P., & Griffith, G. M. (2018). Associations between resilience and the well-being of mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder and other developmental disabilities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(4), 1108–1121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3447-z

Hedley, D., Uljarević, M., Foley, K.-R., Richdale, A., & Trollor, J. (2018). Risk and protective factors underlying depression and suicidal ideation in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 35(7), 648–657. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22759

Hedley, D., Uljarević, M., Wilmot, M., Richdale, A., & Dissanayake, C. (2017). Brief report: Social support, depression and suicidal ideation in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(11), 3669–3677. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3274-2

Higgins, J. M., Arnold, S. R., Weise, J., Pellicano, E., & Trollor, J. N. (2021). Defining autistic burnout through experts by lived experience: Grounded Delphi method investigating #AutisticBurnout. Autism. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613211019858

Hoover, D. W., & Kaufman, J. (2018). Adverse childhood experiences in children with autism spectrum disorder. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 31(2), 128–132. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000390

Iwasaki, Y., MacTavish, J., & MacKay, K. (2010). Building on strengths and resilience: Leisure as a stress survival strategy. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 33(1), 81–100.

Kaboski, J., McDonnell, C. G., & Valentino, K. (2017). Resilience and autism spectrum disorder: Applying developmental psychopathology to optimal outcome. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 4(3), 175–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-017-0106-4

Khanna, R., Jariwala-Parikh, K., West-Strum, D., & Mahabaleshwarkar, R. (2014). Health-related quality of life and its determinants among adults with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(3), 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2013.11.003

Khor, A. S., Melvin, G. A., Reid, S. C., & Gray, K. M. (2014). Coping, daily hassles and behavior and emotional problems in adolescents with high-functioning autism/asperger’s disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(3), 593–608. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1912-x

Kimhi, S., & Eshel, Y. (2015). The missing link in resilience research. Psychological Inquiry, 26(2), 181–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2014.1002378

Lai, M.-C., Kassee, C., Besney, R., Bonato, S., Hull, L., Mandy, W., Szatmari, P., & Ameis, S. H. (2019). Prevalence of co-occurring mental health diagnoses in the autism population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(10), 819–829. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30289-5

Leadbitter, K., Buckle, K. L., Ellis, C., & Dekker, M. (2021). Autistic self-advocacy and the neurodiversity movement: Implications for autism early intervention research and practice. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 635690. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.635690

Ledesma, J. (2014). Conceptual frameworks and research models on resilience in leadership. SAGE Open, 4(3), 215824401454546.

Lee, G. K., Thomeer, M. L., Lopata, C., Schiavo, A. L., Smerbeck, A. M., Volker, M. A., Smith, R. A., & Mirwis, J. E. (2012). Coping strategies and perceived coping effectiveness for social stressors among children with HFASDs: A brief report. Children Australia, 37(3), 108–114. https://doi.org/10.1017/cha.2012.29

Maddox, B. B., & Gaus, V. L. (2019). Community mental health services for autistic adults: Good news and bad news. Autism in Adulthood, 1(1), 15–19. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2018.0006

Maich, K. (2014). Autism spectrum disorders in popular media: Storied reflections of societal views. Brock Education Journal. https://doi.org/10.26522/brocked.v23i2.311

Marcus, L. M. (1984). Coping with Burnout. In E. Schopler & G. B. Mesibov (Eds.), The Effects of Autism on the Family (pp. 311–326). US: Springer.

Martin, D, N. & Bassman, M. (2013). The ever-changing social perception of autism spectrum disorders in the United States. http://uncw.edu/csurf/Explorations/documents/DanielleMartin.pdf.

Masi, A., DeMayo, M. M., Glozier, N., & Guastella, A. J. (2017). An overview of autism spectrum disorder, heterogeneity and treatment options. Neuroscience. Bulletin, 33(2), 183–193.

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56(3), 227–238.

Masten, A. S. (2018). Resilience theory and research on children and families: Past, present, and promise. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 10(1), 12–31.

Masten, A., & Motti-Stefanidi, F. (2020). Multisystem resilience for children and youth in disaster: Reflections in the context of COVID-19. Adversity and Resilience Science, 1(2), 95–106.

Mather, N., & Ofiesh, N. (2005). Resilience and the Child with Learning Disabilities. In S. Goldstein & R. B. Brooks (Eds.), Handbook of Resilience in Children (pp. 239–255). US: Springer.

Matson, J. L., & Kozlowski, A. M. (2011). The increasing prevalence of autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(1), 418–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2010.06.004

Mazurek, M. O. (2013). Social media use among adults with autism spectrum disorders. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1709–1714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.004

McCrimmon, A. W., Matchullis, R. L., & Altomare, A. A. (2014). Resilience and emotional intelligence in children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Developmental Neurorehabilitation. https://doi.org/10.3109/17518423.2014.927017

Migerode, F., Maes, B., Buysse, A., & Brondeel, R. (2012). Quality of life in adolescents with a disability and their parents: The mediating role of social support and resilience. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 24(5), 487–503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-012-9285-1

Morrow Kerns, C. M., Newschaffer, C. J., Berkowitz, S., & Lee, B. K. (2017). Brief report: Examining the association of autism and adverse childhood experiences in the national survey of children’s health: The important role of income and co-occurring mental health conditions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(7), 2275–2281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3111-7

Oliver, M. (2013). The social model of disability: Thirty years on. Disability & Society, 28(7), 1024–1026. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2013.818773

Onyishi, C. N., & Sefotho, M. M. (2019). Predictive impact of resilience on depressive symptoms in adolescents with high functioning autism spectrum disorders. Global Journal of Health Science, 11(14), 73. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v11n14p73

Raymaker, D. M., Teo, A. R., Steckler, N. A., Lentz, B., Scharer, M., Delos Santos, A., Kapp, S. K., Hunter, M., Joyce, A., & Nicolaidis, C. (2020). “Having All of Your Internal Resources Exhausted Beyond Measure and Being Left with No Clean-Up Crew”: Defining autistic burnout. Autism in Adulthood, 2(2), 132–143. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2019.0079

Rosino, M. (2016). ABC-X model of family stress and coping. Encyclopedia of Family Studies. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119085621.wbefs313

Rosqvist, H. B. (2012). Normal for an Asperger: Notions of the meanings of diagnoses among adults with asperger syndrome. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 50(2), 120–128. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-50.2.120

Siqueira, S., & Ahmed, M. (2012). Meditation as a potential therapy for autism: A review. Autism Research and Treatment, 2012, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/835847

Southwick, S., Bonanno, G., Masten, A., Panter-Brick, C., & Yehuda, R. (2014). Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: Interdisciplinary perspectives. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(1), 25338–25414.

Stacey, T.-L., Froude, E. H., Trollor, J., & Foley, K.-R. (2018). Leisure participation and satisfaction in autistic adults and neurotypical adults. Autism, 23(4), 993–1004. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318791275

Steinhardt, M., & Dolbier, C. (2008). Evaluation of a resilience intervention to enhance coping strategies and protective factors and decrease symptomatology. Journal of American College Health, 56(4), 445–453.

Test, D. W., Fowler, C. H., Wood, W. M., Brewer, D. M., & Eddy, S. (2005). A conceptual framework of self-advocacy for students with disabilities. Remedial and Special Education, 26(1), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/07419325050260010601

Teti, M., Cheak-Zamora, N., Lolli, B., & Maurer-Batjer, A. (2016). Reframing autism: Young adults with autism share their strengths through photo-stories. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 31(6), 619–629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2016.07.002

Treweek, C., Wood, C., Martin, J., & Freeth, M. (2019). Autistic people’s perspectives on stereotypes: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Autism, 23(3), 759–769. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318778286

Ungar, M. (2015). Social ecological complexity and resilience processes. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 38, E124.

Ungar, M. (2019). Designing resilience research: Using multiple methods to investigate risk exposure, promotive and protective processes, and contextually relevant outcomes for children and youth. Child Abuse & Neglect, 96, 104098.

Ungar, M., Ghazinour, M., & Richter, J. (2013). Annual Research Review: What is resilience within the social ecology of human development? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(4), 348–366.

Whiteley, P., Carr, K., & Shattock, P. (2019). Is autism inborn and lifelong for everyone? Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 15, 2885–2891. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S221901

Woods, R. (2017). Exploring how the social model of disability can be re-invigorated for autism: In response to Jonathan Levitt. Disability & Society, 32(7), 1090–1095. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1328157

Funding

This article was funded by Dalhousie University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PG was the principal investigator of the project. She designed the study, supported the ethics application, collection of the data, analysis of the data, and writing the manuscript. At the time of the study, SQ was the research assistant of the project and was involved in compiling data and preparing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ghanouni, P., Quirke, S. Resilience and Coping Strategies in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 53, 456–467 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-022-05436-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-022-05436-y