Abstract

Play helps to develop social skills. Children with autism show deviances in their play behavior that may be associated with delays in their social development. In this study, we investigated manipulative, functional and symbolic play behavior of toddlers with and without autism (mean age: 26.45, SD 5.63). The results showed that the quality of interaction between the child and the caregiver was related to the development of play behavior. In particular, security of attachment was related to better play behavior. When the developmental level of the child is taken into account, the attachment relationship of the child with the caregiver at this young age is a better predictor of the level of play behavior than the child's disorder.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Play is important in the development of a child because it allows children to learn and practice new skills in safe and supportive conditions (Boucher 1999). In play children have the opportunity to develop not only motor skills but also cognitive and social skills (e.g. Pellegrini and Smith 1998).

Play shows developmental steps; cognitive development is reflected in, in order, manipulative, functional and symbolic or representational play. First children handle toys in oral and manipulative ways by feeling, licking, sniffing, turning them around, throwing them away, etc. This manipulation creates opportunities to learn about different objects, relations, and about ways to interact and influence the direct environment (Gibson 1988; Piaget 1962; Ruff 1984; Williams 2003). Functional play develops at approximately 14 months of age (Bretherton 1984), and is defined by Ungerer and Sigman (1981) as ‘the appropriate use of an object or the conventional association of two or more objects, such as a spoon to feed the doll, or placing a teacup on a saucer’. The child assigns a function to an object that it contains in daily life, even when an object is miniaturized. Around 24 months of age, symbolic play emerges, although it is difficult to define the point at which play becomes truly ‘symbolic’ (Jarrold et al. 1993). Symbolic play is considered a higher level of play, because it involves pretence, whereas pretence is not necessarily present in functional play.

The social part in play development starts with the step from the child’s playing by itself to noticing the play of others. This social aspect develops further by participating in the play of others, which creates the opportunity to deal with ‘interference’ of others and to develop cooperation skills. Play forms also the context for learning about trust, negotiation and compromise, and with these skills the child has the opportunity to form and maintain friendships (Jordan 2003).

The quality of the relationship with the parent may have an impact on motivational aspects of play behavior as well as on the quality of play. A secure relationship with a trusted attachment figure optimizes the opportunity for the child to explore the environment under safe and supportive conditions (Ainsworth 1978; Bowlby 1982). Indeed it has been found that children with secure attachment relationships display more sophisticated, complex and diverse play during interaction with their mother and during solitary play (e.g., Bornstein et al. 1996; Fiese 1990; Haight and Miller 1992; O’Connell and Bretherton 1984; Slade 1987; Tamis-LeMonda et al. 2002).

Play Behavior and Autism

One of the core deficits in autism is a severe deficit in social behavior. In children with Pervasive Developmental Disorders (PDD) this is demonstrated in play behavior at various levels. Deviations in play behavior can be detected in the first year of life (Ungerer and Sigman 1981; Van Berckelaer-Onnes 2003) and continue through all phases of play development.

The first phase of play development, which involves exploratory/manipulative behavior of objects, is in children with autism characterized by a number of unusual features. They tend to restrict their play to a limited selection of objects (Van Berckelaer-Onnes 2003), or even an isolated part of an object (Freeman et al. 1979). They prefer proximal senses of touch and taste above visual exploration (Williams 2003) and can become intensely preoccupied for long periods of time with non-variable visual examination of just one object (Freeman et al. 1979), or non-play (Ruff 1984), which impairs further development of play (Van Berckelaer-Onnes 2003).

Although several studies reported children with autism to produce the same number of functional acts under spontaneous as well as structured conditions (e.g. Baron-Cohen 1987; Van Berckelaer-Onnes 1994; Charman 1997; Lewis and Boucher 1988; Libby et al. 1998; Williams et al. 2001), it has also been found that children with autism spend significantly less time playing functionally than controls (Lewis and Boucher 1988; Jarrold et al. 1996; Sigman and Ungerer 1984), show lower levels of appropriate object use (Freeman et al. 1984), less variety in their functional play (Sigman and Ungerer 1984), more repetition (Atlas 1990; Williams et al. 2001) and fewer functional acts (e.g. Mundy et al. 1990; Sigman and Ungerer 1984; Ungerer and Sigman 1981).

Children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) may experience particularly difficulties in symbolic play. When symbolic play is performed, their play behavior may be more like ‘learned routine’ rather than spontaneous play (Williams et al. 2001). The lack of this particular type of play in the behavioral repertoire of children with autism does however not necessarily imply a specific impairment in their symbolic abilities. It might reflect a more general cognitive or social deficit associated with autism impinging on the whole range of play development (Jarrold et al. 1993).

This Study

Play behavior in children with autism has been studied before, under various circumstances and on different levels. However, most studies involved subjects older than 42 months of age. The control groups in these studies were mainly subjects matched on mental age (MA), which created substantial differences in chronological age. In this study we investigated play behavior of children with and without ASD, but also of atypically and typically developing controls under the age of 36 months. Several domains of play behavior were analyzed to investigate differences in play behavior between clinical and non-clinical children, and between clinical children with and without ASD. Observing play behavior at this young age provides the opportunity to detect whether the basic play skills of children with ASD are disturbed, or whether the differences appear at a later age when higher levels of play are expected to be shown. We expected the ASD children to lag behind in their level of play behavior already from their first years of life.

Play behavior in children with ASD was also examined in relation to attachment quality. We expected that ASD children with secure attachment relationships would be more playfully engaged and socially involved compared to insecurely attached children with the same disorder. Furthermore, as disorganized attachment is the most insecure type of attachment, it was expected that disorganized children would show more delay in ‘social’ play behavior compared to children without disorganized attachment.

Method

Diagnostic Assessments

This study was part of a study on early screening for autism. For further details regarding recruiting see Dietz et al. (2006), and Swinkels et al. (2006). The children were recruited between the age of 14 and 36 months, based on social developmental delay, but final psychiatric diagnosis was obtained at 42 months. Psychiatric examinations included a series of six visits that were scheduled within a period of 5 weeks. At each weekly visit, the social and communicative behavior of the child was observed in a small group of young children and their parents. The assessments included a standardized parental interview, developmental history, and the Vineland Social-Emotional Early Childhood Scales (Sparrow et al. 1997); the Autism Diagnostic Interview—Revised (ADI—R; Lord et al. 1994); standardized behavior observation (Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule ADOS-G; DiLavore et al. 2000), and pediatric examination and medical work-up. On the basis of all available information, and on the basis of clinical judgment, a diagnosis was given by an experienced child psychiatrist. The inter-rater reliability for two diagnostic categories; ASD or other than ASD was calculated. Agreement among three child psychiatrists (HvE, JB, ED) was reached in 92% of 38 cases. Agreement corrected for chance was 0.74 (Cohen’s Kappa). Agreement for all diagnostic categories was reached in 79% of 38 cases. Agreement corrected for chance was 0.67 (Cohen’s Kappa). Diagnostic discrepancies were resolved at a consensus meeting. If appropriate, children and their parents were offered “care as usual”.

The cognitive level of the child was measured with the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (Mullen 1995).

Diagnostic Groups

Forty-one clinical children participated in this study. At the age of 42 months they were classified with AD (n = 12; mean age 30.25 months (SD 4.81) and developmental level 51.17 (SD 4.06)), PDD-NOS (n = 11; mean age 27.73 months (SD 7.42) and developmental level 71.36 (SD 15.98)), MR (n = 10; mean age 26.50 months (SD 5.38) and developmental level 55.10 (SD 4.09)) or LD (n = 8; mean age 27.75 months (SD 5.68) and developmental level 83.63 (SD 8.48)). No difference in age was detected between the clinical groups, but developmental level was significantly different, F(3, 40) = 23.44, p < .01.

Besides the clinical diagnosis, the groups of children were also divided into the group ASD, including children with AD and PDD-NOS (n = 23, mean age 29.04 months (SD = 6.18) and a mean developmental level 60.83 (SD = 15.19)). The other group (non-ASD) contained children with the developmental disorders MR and LD (n = 18, mean age 27.06 months (SD = 5.38), developmental level 67.78 (SD = 15.85)). No differences in age and developmental level were detected between clinical children with and without ASD.

We included two control groups. One control group contained children who were referred to the hospital due to doubt about the development (AC (Atypical Controls), n = 16). Clinical investigation, however, showed that these children were free from clinical diagnoses. The other control group recruited through well-baby clinics contained typically developing children (NC (normal controls), n = 16). Based on parental reports and observations of the psychologists, these children were free from any child psychiatric disorder.

The group of children with atypical development was younger (AC; M = 20.50, SD = 3.03) compared to the typical developing control group (NC; M = 28.00, SD = 1.75), t = −8.57, p < .01. Although the children in the atypical control group were not showing severe developmental delays, their overall developmental level was lower (AC; M = 85.00, SD = 10.46) compared to the typically developing control group (NC; M = 98.44, SD = 12.18) t = −3.35, p < .01. However, no significant differences were detected in the play behavior of the both control groups.

Descriptive characteristics of the children are presented in Table 1.

Measures

Strange Situation Procedure

Ainsworth (Ainsworth et al. 1978) developed the SSP to observe the attachment behavior of the child towards the mother in a standardized and stressful laboratory setting. The SSP was coded by two trained observers (SS & MBK), who were blind for the diagnoses of the children. Agreement for the four attachment classifications (n = 28) corrected for chance was .74 (Cohen’s Kappa). Besides the attachment classifications, we also used the simplified Richters et al. (1988) algorithm to compute continuous scores for attachment security (Van IJzendoorn and Kroonenberg 1990) on the basis of the interactive SSP scale scores for proximity seeking, contact maintaining, resistance and avoidance. Disorganization was coded using the Main and Solomon (1990) 9-point rating scale for disorganized/disoriented attachment.

Play Behavior

Play behavior was observed according to protocol. The child and the mother were left in the room for ten minutes. The mother was instructed not to stimulate the child to play but to join when the child asked for cooperation in this free play situation. All children received the same set of toys.

Videotapes were coded by means of ‘The Observer’ (Noldus 1991) using an ethogram developed to analyze the play behavior of 2-year-old children, who cannot speak or speak very little. The behaviors mouthing, manipulative play, exploration, functional play, representational play 1 and 2, container play, grouping and stacking 1 and 2 were defined by Largo and Howard (1979). Doll directed play and relational play were derived from Williams et al. (2001). Fenson et al. (1976) provided descriptions of the behaviors symbolic acts and banging. From Leslie’s (1987) definitions of symbolic play, only subject substitution was used.

The various play behaviors were categorized in manipulative, functional or symbolic play, and these variables were used in the analyses. The amount of time that a child spent actually playing was calculated as the percentage of time the child played of the total time of the play session. The amounts of time the child performed manipulative, functional and/or symbolic play, were calculated as percentages of the time spent playing. When the child did not play, it would typically show other behaviors such as sitting passively. Reliability among the three coders for play behavior was based on 50% of the videotapes. Agreement was reached in 92% of 38 cases. Mean agreement corrected for chance was 0.74 (Cohen’s Kappa).

The variable ‘level of play’ was calculated based on the three different levels of play behavior; manipulative, functional and symbolic play. Durations of the three kinds of play behavior were included in the calculation with the following formula: ((1 x duration of manipulative play) + (2 x duration of functional play) + (3 x duration of symbolic play)) / total duration of play. Differential weights were thus assigned to the social and cognitive levels of play. The variable ‘change toys’ was based on the frequency per minute the child initiated play with another toy. The preference of toys was measured by calculating which toys were preferred most during play.

Correlations between play behavior, child characteristics and attachment related variables are presented in Table 2.

Analyses

Play Behavior and Clinical Diagnoses

No gender differences were found for the variables ‘duration of play’, ‘manipulative’, ‘functional’ and ‘symbolic’ play, the ‘overall level of play’ and ‘change toys’. Analyses started with an overall analysis (ANOVA) for all groups, taking differences in developmental level and age into account. Next, differences between the clinical groups with and without ASD were analysed. Preference for toys was investigated using ANOVA for the whole sample, taking differences in developmental level and age into account, and for clinical children with and without ASD.

Contribution of Attachment

To examine whether security of attachment and attachment disorganization contributed to differences in play behavior and preference for toys, analyses with attachment were performed overall, in clinical children and in the group of children with ASD. Play behaviors and preference of toys of children with and without secure attachment, and children with and without disorganized attachment were analyzed.

Results

Duration of Play Behavior

No differences were detected for duration of play time after controlling for difference in age and developmental level (F(5, 72) = 1.87, p = .11). Also, no differences were detected between clinical children with and without ASD (t = −1.09, p = .29). Mean values for the play variables are presented in Table 3.

Manipulative, Functional and Symbolic Play

Overall analysis showed no differences for percentage of time actually spent on manipulative (F(5, 72) = 1.00, p = .43), functional (F(5, 72) = 2.08, p = .08), or symbolic play (F(5, 72) = 1.32, p = .27) when differences in age and developmental level were taken into account. Mean values of the percentage of time for the three different forms of play are presented in Table 3. Neither were differences detected for manipulative play between clinical children with and without ASD (t = −.38, p = .71), for functional play between clinical children with and without ASD (t = −.39, p = .70), and for symbolic play between clinical children with and without ASD (t = −.39, p = .70), when differences in age and developmental level were taken into account. Mean values of the percentage of time for the three different forms of play for clinical children with and without ASD are presented in Table 4.

Level of Play

Level of play, taking differences in developmental level and age into account, did not show any differences between the different groups (F(5, 72) = 1.20, p = .32). Mean values of the level of play are presented in Table 3. Moreover, no differences were detected between clinical children with and without ASD either (t = −.87, p = .39), see Table 4.

Preference for Toys and Change of toys

Analyses were performed for the duration of play that the children were involved with the toys ‘car’, ‘doll’, ‘puzzle’, ‘daily utensils’, bricks’, ‘book’ and ‘ball’, to analyze whether there were any differences in preference for toys. Again, differences in age and developmental level were taken into account. An overall difference was found for playing with ‘daily utensils’ F(5, 72) = 2.53, p = .04. Children with AD spent significant less time playing with daily utensils. Overall differences were also found for reading a book, F(5, 72) = 2.61, p = .03 and playing with a puzzle F(5, 72) = 3.11, p = .01. No differences were detected between children with and without ASD for the time spent playing with daily utensils and playing with a puzzle. However, children with ASD spent significantly less time (M = 2.12, SD = 4.60) reading a book compared to clinical children without ASD (M = 13.11, SD = 17.62), t = −2.88, p < .01.

No differences were detected for changing toys in the overall group, taking differences in age and developmental level into account F(5, 72) = .47, p = .80. Mean values of the frequency of changing toys are presented in Table 3. There were also no differences between the clinical children with and without ASD (t = .37, p = .72), see Table 4.

Quality of Attachment and Play

Children with a secure attachment showed higher levels of play (M = 21.74, SD = 6.32) compared to children without secure attachment (M = 18.24, SD = 6.61), t = −2.18, p = .03. However, because of the higher percentages of secure attachment in children without a clinical disorder, the difference was also tested in the group of children with clinical diagnoses. In the clinical group children with secure attachment (M = 20.88, SD = 7.02) showed significantly higher levels of play than children without a secure attachment relationship (M = 16.35, SD = 5.73) as well, t = −2.20, p = .04.

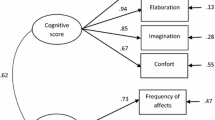

Children with ASD who were securely attached spent more time playing symbolic play compared to children with ASD without a secure attachment (t = −2.37, p = .03). Level of play was also higher in children with ASD with a secure attachment relationship compared to children with ASD without a secure attachment relationship (t = −3.27, p < .01) (Fig. 1). Moreover, children with ASD with a secure attachment relationship spent more time actually playing compared to children with ASD without a secure attachment relationship (t = −2.74, p = .01). The differences within the group of children with ASD with and without secure attachment relationships remained significant after taking differences in age and developmental level into account; for symbolic play F (1, 23) = 4.47, p = .05, for level of play F (1, 23) = 8.88, p < .01, and for duration of play F (1, 23) = 7.19, p = .01, see Table 5.

Disorganized Attachment Relationship and Play

Children with a disorganized attachment classification showed lower levels of play (M = 16.39, SD = 6.83) than children without a disorganized attachment classification (M = 21.32, SD = 6.20), t = 2.51, p = .02. Within the clinical group no difference was shown for level of play of children with and without disorganized attachment. However, children without a disorganized attachment relationship spent more time playing (M = 69.29, SD = 15.67) compared to children with a disorganized attachment classification (M = 55.50, SD = 19.28) t = 2.25, p = .04.

Children with ASD with disorganized attachment showed lower levels of playing than children with ASD without disorganized attachment (t = 2.44, p = .03), see Fig. 1. This difference remained significant after taking differences in age and developmental level into account, F (1, 23) = 5.29, p = .03. Moreover, children with ASD without disorganized attachment spent more time playing compared to children with ASD with disorganized attachment (t = 11.94, p = .02). Again, the difference remained significant after taking differences in age and developmental level into account, F (1, 23) = 9.40, p < .01 (see Table 5).

Children with and without secure or disorganized attachment relationships did not differ on preference for toys.

Discussion

Our findings highlight the importance of attachment in the development of play of children with autism and other developmental disorders. Attachment quality explained play behavior regardless of the clinical status of the children. Taking developmental level of the child into account, we found that children with a secure attachment relationship spent more time playing. They also showed a higher level of play and more symbolic play behavior. Children with a disorganized attachment relationship spent less time playing, and within the group of children with ASD disorganized attachment was related to lower levels of play.

Our earliest understanding about the world and our own actions may have a social rather that a cognitive origin (Hobson 2002; Jordan 2003; Vygotsky 1978). Social deficits belong to the core deficits of children with autism. Nevertheless, children with autism are able to develop a secure attachment relationship with the primary caregiver (Naber et al. 2007; Rutgers et al. 2004), which contributes to better play outcomes in children with autism. We indeed found that children with secure attachment relationships showed more exploration and higher levels of play, whereas children with disorganized attachment showed less exploration, even after controlling for developmental level. Especially in children with autism the quality of attachment relationship was associated with the development of ‘social’ play.

Unexpectedly, for duration of play, level of play or changing toys no differences were detected between children with and without ASD, or even between children with and without a developmental disorder, after controlling for developmental level. Nevertheless, similar to Williams et al. (2001), we found that children with autism preferred toys that were based on ‘simpler’ play behavior. Children with autism did not prefer daily utensils or books to play with.

Several explanations may account for the absence of a difference in most play variables. First, we used a free play situation with the mother. Although the parents were instructed only to follow the child leads and not to structure the setting, the presence of the parent may have motivated the child to continue playing. Second, the lower levels of play behavior typical for this young age period may still be within the reach of children with autism. At a later age, when the children are expected to show symbolic play behavior at higher levels, differences in the amount or quality of symbolic play may emerge. Third, play behavior in children with autism may show delays compared to other children (Beyer and Gammeltoft 2000; Howlin 1986; Lord 1984; Lord and Magill 1989; Wolfberg 1999), but as Jarrold (2003) pointed out, the absence of pretend/symbolic play in children with autism may result from assessing individuals who are (mentally) too young to be expected to show pretend/symbolic play. In the current young age group few children showed much symbolic play, and no difference emerged. Fourth, we used ethological measures to observe play behavior in an objective manner, but the context and coherence or patterning of the behavior was not taken into account. A more holistic approach with global ratings of play behavior may uncover differences between children with and without autism.

Limitations of the Study

Although studies of play behavior are required at an early age to get more insight into its development, the young age of the children is also a limitation because symbolic play was not yet in reach of many subjects in the current study. However, retrospective parental reports and screening studies mention differences in play behavior already at this young age. Longitudinal studies are needed to follow the development of these children’s play across time to see whether differences in play behavior arise at a later stage, and to examine whether the effects of a positive attachment relationship are lasting.

Conclusions and Future Research

As pointed out in a review of Jarrold et al. (1993), studies that indicate a lack of symbolic play behavior in children with autism cannot be seen as convincing proof of the inability of the child to produce this type of play, because MA matched controls would be needed. In our study, we matched the clinical groups both on chronological and on MA. Due to this matching we were able to compare play behavior of children with and without autism. We found no differences in play between children with and without ASD. This may be due to the mental and chronological age of the toddlers included in our study; the lower levels of play behavior typical for this age period may still be within the reach of children with autism. At a later age, children with autism may start to lag behind which might be shown in delayed and infrequent occurrence of symbolic play. We hope to follow-up the current sample to test this interpretation.

What we did find were striking differences between children with and without secure or disorganized attachment relationships. The quality of the parent-child relationship appears to contribute substantially to the development of play in young children regardless of their autistic symptoms. Intervention studies based on play behavior have shown to positively contribute to the development of play in children with ASD during the intervention period. However, no long-term effects have been documented. Our findings show the importance of attachment and suggest that interventions focusing on the improvement of play behavior of children with autism should also focus on enhancing the quality of the attachment relationship. The early intervention study with PDD children by Mahoney and Perales (2005) explored this approach in stimulating cognitive, communicative and socio-emotional functioning. Attachment-based video-feedback intervention has been proven to be effective in typically developing children (Bakermans-Kranenburg et al. 2003; Juffer et al. 2007) and this approach might not only in the short run but also long-term lead to improvement of quality of attachment as well as level of play behavior in children with autism.

References

Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1978). Bowlby-Ainsworth attachment theory cross-cultural studies of attachment organization—recent studies, changing methodologies, and the concept of conditional strategies. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1(3), 436–438.

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, M. C., Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Atlas, J. A. (1990). Play in assessment and intervention in the childhood psychoses. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 21(2), 119–133.

Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Juffer, F. (2003). Less is more: Meta-analyses of sensitivity and attachment interventions in early childhood. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 195–215.

Baron-Cohen, S. (1987). Autism and symbolic play. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 5, 139–148.

Beyer, J., & Gammeltoft, L. (2000). Autism and play. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Bornstein, M. H., Heynes, O. M., O’Reilly, A. W., & Painter, K. M. (1996). Solitary and collaborative pretense play in early childhood: Sources of individual variation in the development of representational competence. Child Development, 67(6), 2910–2929.

Boucher, J. (1999). Pretend play as improvisation: Conversation in the preschool classroom. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 17, 164–165.

Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

Bretherton, I. (1984). Symbolic play. Orlando: Academic Press.

Charman, T. (1997). The relationship between joint attention and pretend play in autism. Development and Psychopathology, 9(1), 1–16.

Dietz, C., Swinkels, S. H. N., Van Daalen, E., Van Engeland, H., Buitelaar, J. K. (2006). Screening for autism spectrum disorders in children aged 14 to 15 months. II: Population screening with the early screening for autism traits (ESAT). Design and general findings. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36, 713–722.

DiLavore, P. C., Lord, C., & Rutter, M. (2000). The pre-linguistic autism diagnostic observation schedule. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 25(4), 355–379.

Fenson, L., Kagan, J., Kearsley, R. B., & Zelazo, P. R. (1976). Developmental progression of manipulative play in 1st 2 years. Child Development, 47(1), 232–236.

Fiese, B. H. (1990). Playful relationships—a contextual analysis of mother–toddler interaction and symbolic play. Child Development, 61(5), 1648–1656.

Freeman, B. J., Guthrie, D., Ritvo, E., Schroth, P., Glass, R., Frankl, F. (1979). Behaviour observation scedule: Preliminary analysis of the similarities and differences between autistic and mentally retarded children. Psychological Reports, 44, 519–24.

Freeman, B. J., Ritvo, E. R., & Schroth, P. C. (1984). Behavior assessment of the syndrome of autism—behavior observation system. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 23(5), 588–594.

Gibson, E. J. (1988). Exploratory behavior in the development of perceiving, acting, and the acquiring of knowledge. Annual Review of Psychology, 39(9), 1–41.

Haight, W. L., & Miller, P. J. (1992). The development of everyday pretend play: A longitudinal study of mothers’ participation. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 38, 301–308.

Hobson, P. (2002). The cradle of thought: Exploring the origins of thinking. London: Macmillan.

Howlin, P. (1986). An overview of social behaviour in autism. Schopler, E. & Mesibov, G. B. (Eds.) New York: Plenum.

Jarrold, C. (2003). A review of research into pretend play in autism. Autism, 7(4), 379–390.

Jarrold, C., Boucher, J., & Smith, P. K. (1993). Symbolic play in autism—A review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 23(2), 281–307.

Jarrold, C., Boucher, J., & Smith, P. K. (1996). Generativity deficits in pretend play in autism. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 14, 275–300.

Jordan, R. (2003). Social play and autistic spectrum disorders—A perspective on theory, implications and educational approaches. Autism, 7(4), 347–360.

Juffer, F., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., en Van IJzendoorn, M.H. (Eds.). (2007). Promoting positive parenting. An attachment-based intervention. Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah.

Largo, R. M., & Howard, J. A. (1979). Development and progression in play behavior of children between nine and thirty months. 1. Spontaneaous play and imitation. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 21(3), 299–310.

Leslie, A. M. (1987). Pretense and representation—The origins of theory of mind. Psychological Review, 94(4), 412–426.

Lewis, V., & Boucher, J. (1988). Spontaneous, instructed and elicited play in relatively able autistic children. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 6, 325–339.

Libby, S., Powell, S, Messer, D., & Jordan, R. (1998). Spontaneous play in children with autism; a reappraisal. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 28, 487–497.

Lord, C. (1984). Development of peer relations in children with autism. F. Morrison, C. Lord, & D. Keating (Eds.), Applied developmental psychology. San Diego, Academic.

Lord, C. & Magill, J. (1989). Methodological and theoretical issues in studying peer-directed behaviour in autism. In G. Dawson (Ed.), Autism: New directions in diagnosis and treatment. New York, Guilford.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., & Le Couteur, A. (1994). Autism diagnostic interview—revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24(5), 659–685.

Mahoney, G., & Perales, F. (2005). Relationship-focused early intervention with children with pervasive developmental disorders and other disabilities: A comparative study. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 26(2), 77–85.

Main M. & Solomon, J. (1990). Procedures for identifying infants as disorganized/disoriented during the Ainsworth strange situation. In M. T. Greenberg D. Cicchetti & E. M. Cummings (Eds.), Attachment in preschool years: Theory, research and intervention. (pp. 121–160). Chicago: University of Chicago press.

Mullen, E. M. (1995). Mullen scales of early learning. Circle Pines: American Guidance Services, Inc.

Mundy, P., Sigman, M., & Kasari, C. (1990). A longitudinal study of joint attention and language development in autistic children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 20(1), 115–128.

Naber, F. B. A., Swinkels, S. H. N., Buitelaar, J. K., Dietz, C., Van Daalen, E., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Van Engeland, H. (2007). Attachment in toddlers with autism and other developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(6), 1123–1138.

Noldus, L. P. J. J. (1991). The Observer—A software system for collection and analysis of observational data. Behavior Research Methods Instruments & Computers, 23(3), 415–429.

O’Connell, B., & Bretherton, I. (1984). Toddlers’ play alone and with mother: The role of maternal guidance. Bretherton, I. Symbolic Play. Orlando: Academic Press.

Pellegrini, A. D., & Smith, P. K. (1998). Physical activity play: The nature and function of a neglected aspect of play. Child Development, 69(3), 577–598.

Piaget, J. (1962). Play, dreams, and imitation in childhood. New York: Norton.

Richters, J. E., Waters, E., & Vaughn, B. E. (1988). Empirical classification of infant–mother relationships from interactive behavior and crying during reunion. Child Development, 59(2), 512–522.

Ruff, H. A. (1984). Infants manipulative exploration of objects—Effects of age and object characteristics. Developmental Psychology, 20(1), 9–20.

Rutgers, A. H., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Van Berckelaer-Onnes, I. A. (2004). Autism and attachment: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(6), 1123–1134.

Sigman, M., & Ungerer, J. A. (1984). Attachment behaviors in autistic children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 14(3), 231–244.

Slade, A. (1987). A longitudinal study of maternal involvement and symbolic play during the toddler period. Child Development, 58(2), 367–375.

Sparrow, S. S., Balla, D. A., & Cicchetti, D. V. (1997). Vineland social-emotional early childhood scales: Manual. Circle Pines: American Guidance Service.

Swinkels, S. H. N., Dietz, C., Van Daalen, E., Kerkhof, I., Van Engeland, H., & Buitelaar, J.K. (2006). Screening for autism spectrum disorders in children aged 14–15 months. 1. The development of the early screening for autistic traits questionnaire. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36, 723–732.

Tamis-LeMonda C. S., Uzgiris I. C., & Bornstein, M. H. (2002). Play in parent–child interactions. M. H. Bornstein, (Ed..) Handbook of parenting Chapter 9. New York: Lawrence Earlbaum associates.

Ungerer, J. A., & Sigman, M. (1981). Symbolic play and language comprehension in autistic children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 20(2), 318–337.

Van Berckelaer-Onnes I. A. (1994). Play training for autistic children. R. van der Kooij J. Hellendoorn, & B. Sutton-Smith (Eds.). Play and intervention. New York: State University of New York Press.

Van Berckelaer-Onnes, I. A. (2003). Promoting early play. Autism, 7(4), 415–423.

Van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Kroonenberg, P. (1990). Cross-cultural consistancy of coding the strange situation. Infant Behavior and Development, 13, 469–485.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychosocial processes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Williams, E. (2003). A comparative review of early forms of object-directed play and parent-infant play in typical infants and young children with autism. Autism, 7(4), 361–377.

Williams, E., Reddy, V., & Costall, A. (2001). Taking a closer look at functional play in children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31(1), 67–77.

Wolfberg, P. (1999). Play and imagination in children with autism. New York: Teachers College Press.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by research grants to Van IJzendoorn and Bakermans-Kranenburg from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO SPINOZA Prize; NWO VIDI Grant 452-04-306), and by research grants to Buitelaar, Swinkels and van Engeland (Korczak Foundation, Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Culture, Cure Autism Now, NWO-MW and NWO-Chronic Diseased, and Preventie Fonds).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Naber, F.B.A., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J., van IJzendoorn, M.H. et al. Play Behavior and Attachment in Toddlers with Autism. J Autism Dev Disord 38, 857–866 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0454-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0454-5