Abstract

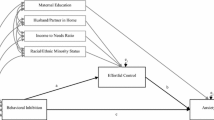

There is increasing recognition of temperamental influences on risk for psychopathology. Whereas the link between the broad temperament construct of negative affectivity (NA) and problems associated with anxiety and depression is now well-established, the mechanisms through which this link operate are not well understood. One possibility involves interactions between reactive and effortful components of temperament, as well as cognitive factors, like attentional biases to threat stimuli. This study tested a predicted relation between high levels of NA, low levels of effortful control (EC), and an attentional bias toward threat in children. A sample of 104 4th through 12th graders, selected from a larger screening sample because they reported high or low levels of trait NA and EC, completed a dot probe detection task. Results indicated that EC moderated the relation between NA and attentional bias; only children with low levels of EC and high levels of NA showed an attentional bias to threat stimuli. This pattern was not moderated by grade level or age.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In this article, we use the label NA, which stems from Rothbart’s theory (Rothbart et al. 1995) but we regard this dimension as largely isomorphic with dimensions in other theories labeled variously Emotionality (Buss and Plomin 1984), Neuroticism (Eysenck 1967), Behavioral Inhibition (Gray and McNaughton 2000), Harm Avoidance (Cloninger 1987), Trait Anxiety (Spielberger 1973), etc. Evidence suggests that these dimensions show a high degree of convergence with one another (see Nigg 2006 for a review). Further, we regard this broad dimension to be closely related to the temperament category of behavioral inhibition (BI) proposed by Kagan and his colleagues (Kagan 1997).

Because this version of the PDT requires participants to read the upper word, their attention starts in the upper word position rather than midway between the two word positions as in versions not requiring the upper word to be read and in which each trial is preceded by a central fixation stimulus. Because the bias toward threat seen in the PDT appears to reflect mainly delayed disengagement from threat cues (see Koster et al. 2004; 2006), the requirement to read the upper word may limit the tasks sensitivity to the bias for upper probes. Instead, the bias would mainly be apparent in trials in which the threat word appears in the upper position but the probe appears in the lower position.

Given the marginal NA x EC interaction for ECS-I, we also conducted this analysis with ECS-I included as a covariate and the results were unchanged. Because ECS-I was unavailable for four participants, it was not included in the main analysis.

The pattern of results was identical for RCMAS scores. Although it was not possible to create extreme groups based on RCMAS scores because participants were selected to be extreme on NA, we conducted a regression analysis in which we substituted continuous RCMAS scores for the NA group variable. Following Aiken and West (1991) we tested the interaction between RCMAS and EC group and found it to be significant, sr = -0.19, p < 0.05. Other variables in this regression model were age, sex, PA, and the RCMAS and EC group main effects.

We are grateful to an anonymous reviewer for suggesting this possibility.

References

Achenbach, T. M., McConaughy, S. H., & Howell, C. T. (1987). Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin, 101, 213–232. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.101.2.213.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression:Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Anthony, J. L., Lonigan, C. J., Hooe, E. S., & Phillips, B. M. (2002). An affect-based, hierarchical model of temperament and its relations with internalizing symptomatology. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 31, 480–490.

Ayduk, O., Mendoza-Denton, R., Mischel, W., & Downey, G. (2000). Regulating the interpersonal self: strategic self-regulation for coping with rejection sensitivity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 776–792. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.776.

Bar-Haim, Y., Lamy, D., Pergamin, L., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2007). Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: a meta-analytic study. Psychological Bulletin, 133, 1–24. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.1.

Biederman, J., Hirshfeld-Becker, D. R., Rosenbaum, J. F., Herot, C., Friedman, D., Snidman, N., Kagan, J., & Faraone, S. V. (2001). Further evidence of association between behavioral inhibition and social anxiety in children. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 158, 1673–1679. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1673.

Boyer, M. C., Compas, B. E., Stanger, C., Colletti, R. B., Konik, B. S., Morrow, S. B., & Thomsen, A. H. (2005). Attentional biases to pain and social threat in children with recurrent abdominal pain. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 31, 209–220. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsj015.

Buss, A. H., & Plomin, R. (1984). Temperament: Early developing personality traits. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Erlbaum.

Calkins, S. D., & Fox, N. A. (2002). Self-regulatory processes in early personality development: a multilevel approach to the study of childhood social withdrawal and aggression. Development and Psychopathology, 14, 477–498. doi:10.1017/S095457940200305X.

Capaldi, D. M., & Rothbart, M. K. (1992). Development and validation of an early adolescent temperament measure. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 12, 153–173. doi:10.1177/0272431692012002002.

Caseras, X., Garner, M., Bradley, B. P., & Mogg, K. (2007). Biases in visual orienting to negative and positive scenes in dysphoria: an eye movement study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116, 491–497. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.116.3.491.

Caspi, A., Henry, B., McGee, R. O., Moffitt, T. E., & Silva, P. A. (1995). Temperamental origins of child and adolescent behavior problems: from age three to age fifteen. Child Development, 66, 55–68. doi:10.2307/1131190.

Clark, L. A., Watson, D., & Mineka, S. (1994). Temperament, personality, and the mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103, 103–116. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.103.1.103.

Cloninger, C. R. (1987). Neurogenetic adaptive mechanisms in alcoholism. Science, 236, 410–416.

Cole, D. A., Truglio, R., & Peeke, L. (1997). Relation between symptoms of anxiety and depression in children: a multitrait–multimethod–multigroup assessment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65, 110–119. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.65.1.110.

Compas, B. E., Connor-Smith, J., & Jaser, S. S. (2004). Temperament, stress reactivity, and coping: implications for depression in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 21–31. doi:10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_3.

Dalgleish, T., Taghavi, R., Neshat-Doost, H., Moradi, A., Canterbury, R., & Yule, W. (2003). Patterns of processing bias for emotional information across clinical disorders: a comparison of attention, memory, and prospective cognition in children and adolescents with depression, generalized anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 32, 10–21.

Dandeneau, S. D., & Baldwin, M. W. (2004). The inhibition of socially rejecting information among people with high versus low self-esteem: the role of attentional bias and the effects of bias reduction training. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23, 584–602. doi:10.1521/jscp.23.4.584.40306.

Dandeneau, S. D., Baldwin, M. W., Baccus, J. R., Sakellaropoulo, M., & Pruessner, J. C. (2007). Cutting stress off at the pass: reducing vigilance and responsiveness to social threat by manipulating attention. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 651–666. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.93.4.651.

Degnan, K. A., & Fox, N. A. (2007). Behavioral inhibition and anxiety disorders: multiple levels of a resilience process. Development and Psychopathology, 19, 729–746. doi:10.1017/S0954579407000363.

Derryberry, D., & Rothbart, M. K. (1997). Reactive and effortful processes in the organization of temperament. Development and Psychopathology, 9, 633–652. doi:10.1017/S0954579497001375.

Derryberry, D., & Reed, M. A. (1996). Regulatory processes and the development of cognitive representations. Development and Psychopathology, 8, 215–234.

Derryberry, D., & Reed, M. A. (2002). Anxiety-related attentional biases and their regulations by attentional control. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111, 225–23. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.111.2.225.

Derryberry, D., & Rothbart, M. K. (1997). Reactive and effortful processes in the organization of temperament. Development and Psychopathology, 9, 633–652. doi:10.1017/S0954579497001375.

Eisenberg, N., Cumberland, A., Spinrad, T. L., Fabes, R. A., Shepard, S. A., Reiser, M., Murphy, B. C., Losoya, S. H., & Guthrie, I. K. (2001). The relations of regulation and emotionality to children’s externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Child Development, 72, 1112–1134. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00337.

Eisenberg, N., Sadovsky, A., Spinrad, T. L., Fabes, R. A., Losoya, S. H., Valiente, C., Reiser, M., Cumberland, A., & Shepard, S. A. (2005). The relations of problem behavior status to children’s negative emotionality, effortful control, and impulsivity: concurrent relations and prediction of change. Developmental Psychology, 41, 193–211. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.41.1.193.

Ehrenreich, J. T., & Gross, A. M. (2002). Biased attentional behavior in childhood anxiety: a review of theory and current empirical investigation. Clinical Psychology Review, 22, 991–1008. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(01)00123-4.

Eysenck, H. J. (1967). The biological basis of personality. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas.

Field, A. P. (2006). The behavioral inhibition system and the verbal information pathway to children’s fears. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115, 742–752. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.742.

Fox, N. A., Henderson, H. A., Marshall, P. J., Nichols, K. E., & Ghera, M. M. (2005). Behavioral inhibition: linking biology and behavior within a developmental framework. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 235–262. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141532.

Frick, P. J. (2004). Integrating research on temperament and childhood psychopathology: its pitfalls and promise. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 2–7. doi:10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_1.

Garber, J., Van Slyke, D. A., & Walker, L. S. (1998). Concordance between mothers’ and children’s reports of somatic and emotional symptoms in patients with recurrent abdominal pain or emotional disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26, 381–391. doi:10.1023/A:1021955907190.

Gladstone, G. L., Parker, G. B., Mitchell, P. B., Wilhelm, K. A., & Malhi, G. S. (2005). Relationship between self-reported childhood behavioral inhibition and lifetime anxiety disorders in a clinical sample. Depression and Anxiety, 22, 133–143. doi:10.1002/da.20082.

Gray, J. A., & McNaughton, N. (2000). The neuropsychology of anxiety (2nd ed.). London: Oxford University Press.

Hadwin, J. A., Garner, M., & Perez-Olivas, G. (2006). The development of information processing biases in childhood anxiety: a review and exploration of its origins in parenting. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 876–894. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.09.004.

Hazen, R. A., Vasey, M. W., & Schmidt, N. B. (in press) Attentional retraining: a randomized clinical trial for pathological worry. Journal of Psychiatric Research.

Hirshfeld, D. R., Rosenbaum, J. F., Biederman, J., Bolduc, E. A., Faraone, S. V., Snidman, N., Reznick, J. S., & Kagan, J. (1992). Stable behavioral inhibition and its association with anxiety disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 31, 103–111. doi:10.1097/00004583-199201000-00016.

Hodges, K., Gordon, Y., & Lennon, M. P. (1990). Parent–child agreement on symptoms assessed via a clinical research interview for children: the child assessment schedule (CAS). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 31, 427–436. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1990.tb01579.x.

Hunt, C., Keogh, E., & French, C. C. (2006). Anxiety sensitivity, conscious awareness and selective attentional biases in children. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 497–509. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2006.04.001.

John, O. P., Caspi, A., Robins, R. W., Moffitt, T. E., & Stouthamer-Loeber, M. (1994). The “little five”: exploring the nomological network of the five-factor model of personality in adolescent boys. Child Development, 65, 160–178. doi:10.2307/1131373.

Joormann, J., & Gotlib, I. H. (2007). Selective attention to emotional faces following recovery from depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116, 80–85. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.80.

Joormann, J., Talbot, L., & Gotlib, I. H. (2007). Biased processing of emotional information in girls at risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116, 135–143. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.135.

Kagan, J. (1997). Temperament and the reactions to unfamiliarity. Child Development, 68, 139–143. doi:10.2307/1131931.

Kagan, J., Snidman, N., Zentner, M., & Peterson, E. (1999). Infant temperament and anxious symptoms in school age children. Development and Psychopathology, 11, 209–224. doi:10.1017/S0954579499002023.

Koster, E. H. W., Crombez, G., Verschuere, B., & De Houwer, J. (2004). Selective attention threat in the dot probe paradigm: differentiating vigilance and difficulty to disengage. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42, 1183–1192. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2003.08.001.

Koster, E. H. W., Crombez, G., Verschuere, B., & De Houwer, J. (2006). Attention to threat in anxiety-prone individuals: mechanisms underlying attentional bias. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 30, 635–643. doi:10.1007/s10608-006-9042-9.

Lonigan, C. J. (1998). Development of a measure of effortful control in school-age children. Unpublished raw data. Florida State University.

Lonigan, C. J., Vasey, M. W., Phillips, B. M., & Hazen, R. A. (2004). Temperament, anxiety, and the processing of threat-relevant stimuli. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 8–20. doi:10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_2.

Lonigan, C. J., Hooe, E. S., David, C. F., & Kistner, J. A. (1999). Positive and negative affectivity in children: confirmatory factor analysis of a two-factor model and its relation to symptoms of anxiety and depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 374–386. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.67.3.374.

Lonigan, C. J., & Phillips, B. M. (2001). Temperamental basis of anxiety disorders in children. In M.W. Vasey & M.R. Dadds (Eds.), The developmental psychopathology of anxiety pp. 60–91. Oxford University Press.

Lonigan, C. J., & Phillips, B. M. (2002). Longitudinal relations between effortful control, affectivity, and symptoms of psychopathology in children and adolescents. Unpublished raw data. Florida State University.

Lonigan, C. J., Phillips, B. M., & Hooe, E. S. (2003). Tripartite model of anxiety and depression in children: evidence from a latent variable longitudinal study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 465–481. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.71.3.465.

MacLeod, C., & Mathews, A. (1988). Anxiety and the allocation of attention to threat. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 40A, 653–670.

MacLeod, C., Mathews, A., & Tata, P. (1986). Attentional bias in emotional disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 95, 15–20. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.95.1.15.

MacLeod, C., Rutherford, E., Campbell, L., Ebsworthy, G., & Holker, L. (2002). Selective attention and emotional vulnerability: assessing the causal basis of their association through the experimental manipulation of attentional bias. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111, 107–123. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.111.1.107.

Mathews, A. (2004). On the malleability of emotional encoding. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42, 1019–1036. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2004.04.003.

Mathews, A., Ridgeway, V., & Williamson, D. A. (1996). Evidence for attention to threatening stimuli in depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34, 695–705. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(96)00046-0.

Mathews, A., Yiend, J., & Lawrence, A. D. (2004). Individual differences in the modulation of fear-related brain activation by attentional control. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 16, 1683–1694. doi:10.1162/0898929042947810.

Mogg, K., Mathews, A., & Eysenck, M. (1992). Attentional bias in clinical anxiety states. Cognition and Emotion, 6, 149–159. doi:10.1080/02699939208411064.

Mogg, K., Mathews, A., & Weinman, J. (1989). Selective processing of threat cues in clinical anxiety states: a replication. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 27, 317–323. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(89)90001-6.

Mogg, K., Millar, N., & Bradley, B. P. (2000). Biases in eye movements to threatening facial expressions in generalized anxiety disorder and depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 695–704.

Muris, P. (2006). Unique and interactive effects of neuroticism and effortful control on psychopathological symptoms in non-clinical adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 40, 1409–1419. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.12.001.

Muris, P., De Jong, P. J., & Engelen, S. (2004). Relationships between neuroticism, attentional control, and anxiety disorders symptoms in non-clinical children. Personality and Individual Differences, 37, 789–797. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2003.10.007.

Muris, P., Meesters, C., & Spinder, M. (2003). Relationships between child- and parent-reported behavioural inhibition and symptoms of anxiety and depression in normal adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 34, 759–771. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00069-7.

Muris, P., Meesters, C., & Blijlevens, P. (2007). Self-reported reactive and regulative temperament in early adolescence: relations to internalizing and externalizing problem behavior and “Big Three” personality factors. Journal of Adolescence, 30, 1035–1049. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.03.003.

Muris, P., & Ollendick, T. H. (2005). The role of temperament in the etiology of child psychopathology. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 8, 271–289. doi:10.1007/s10567-005-8809-y.

Neshat-Doost, H. T., Moradi, A. R., Taghavi, M. R., Yule, W., & Dalgleish, T. (2000). Lack of attentional bias for emotional information in clinically depressed children and adolescents on the dot probe task. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 41, 363–368. doi:10.1017/S0021963099005429.

Nigg, J. T. (2006). Temperament and developmental psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 47, 395–422. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01612.x.

Oldehinkel, A. J., Hartman, C., Ferdinand, R. F., Verhulst, F. C., & Ormel, J. (2007). Effortful control as modifier of the association between negative emotionality and adolescent’s mental health problems. Development and Psychopathology, 19, 523–539. doi:10.1017/S0954579407070253.

Patrick, C. J., & Bernat, E. M. (2006). The construct of emotion as a bridge between personality and psychopathology. In R. F. Krueger, & J. L. Tackett (Eds.), Personality and psychopathology (pp. 174–209). New York: Guilford.

Phillips, B. M., Lonigan, C. J., Driscoll, K., & Hooe, E. S. (2002). Positive and negative affectivity in children: a multitrait-multimethod evaluation. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 31, 465–479.

Posner, M. I. (1980). Orienting of attention. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 32, 3–25. doi:10.1080/00335558008248231.

Posner, M. R., & Rothbart, M. K. (2000). Developing mechanisms of self-regulation. Development and Psychopathology, 12, 427–441. doi:10.1017/S0954579400003096.

Prior, M., Smart, D., Sanson, A., & Oberklaid, F. (2000). Does shy-inhibited temperament in childhood lead to anxiety problems in adolescence? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 461–468. doi:10.1097/00004583-200004000-00015.

Puliafico, A. C., & Kendall, P. C. (2006). Threat-related attentional bias in anxious youth: a review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 9, 162–180. doi:10.1007/s10567-006-0009-x.

Rapee, R. M. (2002). The development and modification of temperamental risk for anxiety disorders: prevention of a lifetime of anxiety? Biological Psychiatry, 52, 947–957. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01572-X.

Rende, R. D. (1993). Longitudinal relations between temperament traits and behavioral syndromes in middle childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 32, 287–290. doi:10.1097/00004583-199303000-00008.

Reynolds, C. R., & Paget, K. D. (1981). Factor analysis of the revised children’s manifest anxiety scale for blacks, whites, males, and females with a national normative sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 49, 352–359. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.49.3.352.

Reynolds, C. R., & Richmond, B. O. (1978). What I think and feel: a revised measure of children’s manifest anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 67, 271–280. doi:10.1007/BF00919131.

Reynolds, C. R., & Richmond, B. O. (1985). Revised children’s manifest anxiety scale. LA: Western Psychological Services.

Rinck, M., & Becker, E. S. (2005). A comparison of attentional biases and memory biases in women with social phobia and major depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114, 62–74. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.62.

Rothbart, M. K. (1989). Temperament and development. In G. A. Kohnstamm, J. E. Bates, & M. K. Rothbart (Eds.), Temperament in childhood (pp. 187–247). New York: Wiley.

Rothbart, M. K., & Bates, J. E. (1998). Temperament. In W. Damon, & N. Eisenberg (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (pp. 105–176, 5th ed.). New York: Wiley.

Rothbart, M. K., Posner, M. I., & Hershey, K. L. (1995). Temperament, attention, and developmental psychology. In D. Cicchetti, & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology. Volume 1: Theory and methods. 315–340: New York: Wiley.

Rowe, D. C., & Kandel, D. (1997). In the eye of the beholder? Parental ratings of externalizing and internalizing symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 25, 265–275. doi:10.1023/A:1025756201689.

Schippell, P. L., Vasey, M. W., Cravens-Brown, L. M., & Bretveld, R. (2003). Suppressed attention to rejection, ridicule, and failure cues: a specific correlate of reactive but not proactive aggression in youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 32, 40–55.

Schwartz, C. E., Snidman, N., & Kagan, J. (1999). Adolescent social anxiety as an outcome of inhibited temperament in childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38, 1008–1015.

Spielberger, C. (1973). Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory for children. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Taghavi, M. R., Neshat Doost, H. T., Moradi, A. R., Yule, W., & Dalgleish, T. (1999). Biases in visual attention in children and adolescents with clinical anxiety and mixed anxiety-depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 27, 215–223. doi:10.1023/A:1021952407074.

Treiber, F. A., & Mabe, P. A. (1987). Child and parent perceptions of children’s psychopathology in psychiatric outpatient children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 15, 115–124. doi:10.1007/BF00916469.

Vasey, M. W. (2008). Comparison of the attentional control scale and the ec scale in a youth sample. Unpublished raw data. The Ohio State University.

Vasey, M. W., Daleiden, E. L., Williams, L. L., & Brown, L. M. (1995). Biased attention in childhood anxiety disorders: a preliminary study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 23, 267–279. doi:10.1007/BF01447092.

Vasey, M. W., Dalgleish, T., & Silverman, W. K. (2003). Research on information-processing factors in child and adolescent psychopathology: a critical commentary. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 32, 81–93.

Vasey, M. W., El-Hag, N., & Daleiden, E. L. (1996). Anxiety and the processing of emotionally-threatening stimuli: distinctive patterns of selective attention among high- and low-test-anxious children. Child Development, 67, 1173–1185. doi:10.2307/1131886.

Vasey, M. W., & MacLeod, C. (2001). Information-processing factors in childhood anxiety: A review and developmental perspective. In M. W. Vasey, & M. R. Dadds (Eds.), The developmental psychopathology of anxiety (pp. 253–277). New York: Oxford University Press.

Waters, A. M., Lipp, O. V., & Spence, S. H. (2004). Attentional bias toward fear-related stimuli: an investigation with nonselected children and adults and children with anxiety disorders. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General, 89, 320–327.

Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1991). Self- versus peer ratings of specific emotional traits: evidence of convergent and discriminant validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 927–940.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063.

Watts, S. E., & Weems, C. F. (2006). Associations among selective attention, memory bias, cognitive errors and symptoms of anxiety in youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34, 841–852. doi:10.1007/s10802-006-9066-3.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported, in part, by a grant to Christopher Lonigan from the Florida State University, Council on Research and Creativity. Views expressed herein are those of the authors and have not been reviewed or approved by the grantor.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lonigan, C.J., Vasey, M.W. Negative Affectivity, Effortful Control, and Attention to Threat-Relevant Stimuli. J Abnorm Child Psychol 37, 387–399 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-008-9284-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-008-9284-y