Abstract

This paper assembles a new dataset on corporate income tax regimes in 50 emerging and developing economies over 1996–2007 and analyzes their impact on corporate tax revenues and domestic and foreign investment. It computes effective tax rates to take account of special regimes, such as tax holidays, temporarily reduced rates and increased investment allowances. There is evidence of a partial race to the bottom: countries have been under pressure to lower tax rates in order to lure and boost investment. In the case of standard tax systems (i.e. tax rules applying under normal circumstances), the effective tax rate reductions have not been larger than those witnessed in advanced economies, and revenues have held up well over the sample period. However, a race to the bottom is evident among special regimes, most notably in the case of Africa, creating effectively a parallel tax system where rates have fallen to almost zero. Regression analysis reveals higher tax rates adversely affect domestic investment and FDI, but do raise revenues in the short run.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The literature is summarized in Wilson (1999), and more recently Fuest et al. (2005). Most early tax competition models are based on the idea that globalization increases the elasticity of capital with respect to taxation. This increases the marginal cost of raising public funds and therefore reduces welfare. However, when other taxes are available, such as taxes on less mobile factors, or if governments raise taxes for reasons other than welfare maximization, then tax competition can be less harmful or even beneficial in some models.

We use the term “developing and emerging” country loosely and include as many economies of growing importance as we could cover with our data. Some of them are indeed advanced economies under the WEO classification, e.g., Israel.

Many more papers exist that focus on one or a few countries or at best a region, but without a wide panel it is hard to draw general lessons from country experiences.

The country’s ranking on the two measures may not be the same. For instance, a country with a high statutory rate and generous allowances will have a high EATR, because the investment allowance will make up for a small share of profits, but a low EMTR, because the generous allowance may cover most or all of the tax liability, reducing the relevance of the statutory tax rate.

Unlike the EMTR of Chen and Mintz (2008), our estimates do not attempt to incorporate other business taxes, such as asset-based taxes and sales taxes on capital inputs.

As it is possible that the largest economies follow different trends, we have also looked at Brazil, India and China. Among these, only India implemented major reforms to the standard tax system, cutting the statutory tax rate significantly and regularly from 46 % in 1996 to 34 % in 2007, while making the tax base narrower through more generous depreciation allowances for plant and machinery.

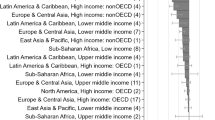

To generate the regional average for a given year, the most generous regime was identified for each country within the region in that year, and a simple average taken of the corresponding effective tax rates across countries.

Again we looked separately at Brazil, China, and India and found that India cut its tax holiday from 10 to 5 years, while the most generous regime in China remained unchanged. Brazil does not use tax holidays falling under our definition of broad applicability.

Temporary (one-year) reversals of 1 percentage point were not deemed to interrupt an episode. Thus if country i reduced its EATR from 20 percent in 2000 to 17 percent in 2001, then raised it 18 percent in 2002, but resumed the downward reduction till say, 2004, to a level of 15 percent, the episode was recorded as a 5 percentage point reduction starting in 2000 and ending in 2004.

Turkey, Mexico and Estonia are excluded because of the very large changes in their EMTRs: Turkey (3 yrs, starting 2003, +330 percentage points); Mexico (3 yrs, starting 1996, +250 percentage points); Turkey (1 yr, starting 1998, −300 percentage points); and Estonia (1 yr, starting 1998, −130 percent). Inclusions of these episodes would skew the reported averages.

Clausing (2007) additionally splits the ratio of profits over GDP into the product of the ratio of profits to value added and value added to GDP, but we do not have data on corporate value added.

We systematically use standard errors that are robust to heteroskedasticity and within-group serial correlation. Hausman tests reject the random effect in favor of the fixed effect model for most regressions, and we use fixed effect estimators throughout for consistency.

We are interested in the ratio of the tax base to profits. This ratio is greater than 1 if the tax base is broad, i.e., if deductions are smaller than true economic costs. This ratio can therefore be proxied by the ratio of the PDVs of true economic deprecation to statutory depreciation, which is equally exceeds 1 if the tax base is broad.

Like Clausing (2007), we cannot directly control for changes in the tax base that result from behavioral changes, as we do not have the required data.

Klemm and Van Parys (2012) consider the related issue of the impact on tax incentives on investment in African, Latin American and Caribbean countries. They find that FDI is responsive to the tax rate and some tax incentives, while total private investment is not.

This is also in line with Klemm and Van Parys (2012) who find no impact of tax incentives on investment.

References

Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87, 11–143.

Bucovetsky, S. (1991). Asymmetric tax competition. Journal of Urban Economics, 30, 167–181.

Chen, D., & Mintz, J. (2008). Taxing business investments: a new ranking of effective tax rates on capital. Washington: World Bank.

Clausing, K. (2007). Corporate tax revenues in OECD countries. International Tax and Public Finance, 14, 115–133.

De Mooij, R. A., & Ederveen, S. (2003). Taxation and foreign direct investment: a synthesis of empirical research. International Tax and Public Finance, 10(6), 673–693.

De Mooij, R. A., & Ederveen, S. (2008). Corporate tax elasticities: a reader’s guide to empirical findings. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 24(4), 680–697.

Devereux, M., & Griffith, R. (2003). Evaluating tax policy for location decisions. International Tax and Public Finance, 10, 107–126.

Devereux, M. P., Griffith, R., & Klemm, A. (2002). Corporate income tax reforms and international tax competition. Economic Policy, 17(35), 451–495.

European Commission, (1992). Report of the independent experts on company taxation. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Fuest, C., Huber, B., & Mintz, J. (2005). Capital mobility and tax competition. Foundations and Trends in Microeconomics, 1(1), 1–62.

Gugl, E., & Zodrow, G. (2006). International tax competition and tax incentives in developing countries. In J. Alm, J. Martinez-Vazquez, & M. Rider (Eds.), The challenge of tax reform in a global economy (pp. 167–191). Berlin: Springer.

Hines, J. R. (1999). Lessons from behavioral responses to international taxation. National Tax Journal, 52(2), 305–322.

Janeba, E., & Smart, M. (2003). Is targeted tax competition less harmful than its remedies? International Tax and Public Finance, 10, 259–280.

Keen, M. (2002). Preferential regimes can make tax competition less harmful. National Tax Journal, 54(2), 757–762.

Keen, M., & Mansour, M. (2010). Revenue mobilization in sub-Saharan Africa: challenges from globalization II—corporate taxation. Development Policy Review, 28(5), 573–596.

Keen, M., & Simone, A. (2004). Is tax competition harming developing countries more than developed? Tax Notes International, Special Issue 28, 1317–1325.

Klemm, A. (2010). Causes, benefits, and risks of business tax incentives. International Tax and Public Finance, 17(3), 315–336.

Klemm, A. (2012). Effective average tax rates for permanent investment. Journal of Economic and Social Measurement, 37(3), 253–264.

Klemm, A., & Van Parys, S. (2012). Empirical evidence on the effects of tax incentives. International Tax and Public Finance, 19(3), 393–423.

Mintz, J. (1990). Corporate tax holidays and investment. World Bank Economic Review, 4(1), 81–102.

Nickell, S. (1981). Biases in dynamic models with fixed effects. Econometrica, 49(6), 1417–1426.

OECD (1991). Taxing profits in a global economy: domestic and international issues. Paris: OECD.

OECD (2001). Corporate tax incentives for foreign direct investment. OECD tax policy study, No. 4.

Shah, A. (Ed.) (1995). Fiscal incentives for investment and innovation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wilson, J. (1999). Theories of tax competition. National Tax Journal, 52(2), 269–304.

Zee, H., Stotsky, J., & Ley, E. (2002). Tax incentives for business investment: a primer for policy makers in developing countries. World Development, 30(9), 1497–1516.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like thank Oliver Denk, Mike Devereux, Jost Heckemeyer, Mick Keen, Paolo Mauro, Ruud de Mooij, ECB, IMF, ETPF, and IIPF seminar participants and two anonymous referees for useful comments and Asad Zaman for excellent research assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Article written with contributions by Sukhmani Bedi (INSEAD School of Business) and Junhyung Park (UCLA).

This paper should not be reported as representing the view of the IMF or the ECB.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Data sources and assumptions

The total tax and corporate tax revenue data was obtained from IMF country desks. For comparability purposes, social security revenue and, for oil producing countries, oil revenues, were excluded from both corporate and total taxes. In the case of oil producers, non-oil taxes were scaled to non-oil GDP. Gross operating surplus was sourced from the United Nations (accessed from: http://unstats.un.org/unsd/databases.htm). All other macroeconomic variables are from the World Economic Outlook database.

Information on statutory corporate income tax rates, depreciation regimes, investment allowances, and special regimes, were all sourced from the Corporate Tax Guides published by Price Waterhouse Coopers and Ernst and Young during 1996 and 2007. Some assumptions were needed during the extraction of this data, which are as follows:

-

We only considered tax incentives with broad applicability, such as the manufacturing or export sector. We did not collect data on more limited incentives, such as investments in backward areas, research and development or production with high technology content.

-

Where the size of a tax allowance depended on the extent of foreign partnership, we assumed the level of partnership delivering the highest tax allowance.

-

Where the tax guides did not specify the depreciation method, or allowed firms to choose between straight line and reducing balance, the former was assumed.

-

In cases where the duration over which assets are to be depreciated was not mentioned, 10 years was assumed for plant and machinery and 20 years for buildings (when a range was provided, an average was taken).

-

We ignore incentives on reinvested incomes, so that the derived rates represent what would apply to fresh investments.

-

To adjust for different fiscal years, the tax rate applicable to the larger part of the financial year was taken as the tax rate for that year.

-

Effective tax rates were calculated at the corporate level (i.e., ignoring personal taxes on dividends, interest and capital gains).

-

For effective tax rate calculations we assume investment in plant and machinery, equity finance, an inflation rate of 3.5 %, a real interest rate of 10 %, true economic depreciation of 12¼ %. For the EATR we assume a profit rate of 20 %.

Appendix 2: Episodes of large effective tax rate changes (1996–2007)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abbas, S.M.A., Klemm, A. A partial race to the bottom: corporate tax developments in emerging and developing economies. Int Tax Public Finance 20, 596–617 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-013-9286-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-013-9286-8

Keywords

- Effective tax rates

- Corporate income tax

- Investment

- Special economic zones

- Emerging markets

- Low-income countries

- Developing economies