Abstract

Most of the early empirical estimates on effects of intergovernmental grants contradict theoretical predictions. In the more recent literature that emphasizes the importance of convincing empirical strategies, the results are more mixed. This paper contributes to this literature by estimating causal effects on local expenditures and income taxes of general, unconditional grants. This is done in a difference-in-difference model utilizing policy-induced increases in grants to a group of remotely populated municipalities in Finland. The finding is that increased grants have a statistically and economically significant positive immediate effect on local expenditures. The effect on local income taxes, while statistically significant, is considerably smaller in magnitude. Furthermore, there is no evidence of dynamic crowding-out—i.e., that the immediate response in expenditures is reversed in later years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

These predictions vary depending on the type of grant (e.g., conditional or unconditional). And while the predictions also depend on the model use, in general they seem quite robust to various assumptions. For example, the analysis in Bradford and Oates (1971), who were among the first to incorporate political aspects of grants, by and large sticks to this prediction.

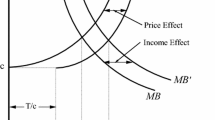

Since matching grants induce both an income and a positive price effect, theoretically matching grants should stimulate expenditures more than non-matching, unconditional grants. In practice, however, matching occurs in most cases only up to a certain amount of expenditures above which receiving jurisdictions are often spending. This implies that also matching grants effectively induce a pure income effect.

Statistics Finland has an awkward way of dealing with consolidated municipalities. For example, if municipality A joined municipality B in year 2001, in new data sets A’s population will be added to that of B even in earlier years than 2001. For some variables, this procedure makes more or less sense, while for others (e.g., tax rates or political majority) it makes no sense at all. Consequently, there is no good option but to drop all consolidated municipalities from the data.

Most municipalities operate independently, but some cooperate with one another and provide services through so-called joint authorities, an arrangement most common in the health sector.

Unless indicated otherwise, from hereon tax revenues refer to this constructed variable. The reason for not studying actual tax revenues is that only the tax rate is under local discretion. The tax base, on the other hand, reflects individual labor supply decisions and is therefore quite variable. This makes actual tax revenues a much noisier variable.

As shown in Sect. 4.2, the policy-induced increase in the grant to remotely populated municipalities indeed induced corresponding increases in the broader grant categories. Whether or not the increase was sufficiently large to yield any behavioral response is then, of course, an empirical question.

The increase in per capita expenditures is around 630 euro in the treatment group and 460 euro in the control group. The corresponding increases in per capita tax revenues are 17 and 37 euro. In a formal means test, all these four increases are statistically significant at the 1 % level.

The remote index assignment in the period studied here took place in 2002.

In 2006, a new grant system came into place where this as well as many other grant types were changed considerably, but due to lack of data, the figure only illustrates how the supplemental grant was distributed during 1998–2004.

The reform is proposed by the government in Bill 128/2001 and legislated in Law 1360/2001.

Combining Figs. 2 and 3 suggests that, because of the counteracting effect from decreased transitory grants, for group 3 the supplemental grant increase was not associated with an overall grant increase, and could thus not have caused any behavioral response. An analysis of the municipalities in this group—from which results are available upon request—indeed shows this to be case.

Recall from the previous section that only the tax rate is under local discretion and that unless indicated otherwise, tax revenues refer to the constructed variable measuring tax revenues keeping the tax base fixed at the pre-treatment level.

Note that Finnish municipalities do not have a balanced budget requirement and are allowed to take up loans.

See Gordon (2004).

Note that, just as τ in Eq. (2) is a parameter for the total change between the pre- and post-treatment period, τ 2001–τ 2004 are parameters for the specific annual changes. Technically, the year-specific estimates are obtained by interacting SG i with year dummies.

It may be worth noting that the specification in (3) identifies the average treatment effects (ATE) on the treated if responses to treatment are heterogeneous. That is, even though the outcome of the control group serves as the potential outcome of the treatment group had it not been treated, the opposite cannot be assumed to hold unless treatment effects are constant. This is always the case in standard DID models. In contrast, Athey and Imbens (2006) develop an approach that also identifies the ATE on the untreated (and consequently the overall ATE) even in the presence of heterogeneous effects.

Although non-parallel pre-treatment trends do, in principle, not completely rule out parallel counterfactual post-treatment trends (and vice versa).

Using, instead of constructed tax revenues as in Table 3, actual tax revenues (i.e., tax rates times tax base) yields a statistically significant estimate of the total effect τ of −0.38 (to be compared to −0.27). When broken down over the separate years, however, the pattern of tax rate changes implied by Table 3 cannot be reproduced. As noted above, a likely reason for this is that the tax base is quite variable, making it harder to detect whether or not the municipality has changed its tax rate (which is the only tax instrument under local discretion). With this in mind, it is noteworthy that the baseline results are robust to controlling for the per capita tax base; see Sect. 4.3 below.

Note that transitory grants are not included in total grants, G i,t , as defined and used in the 2SLS analysis above.

Corporate tax revenues are not available for the years 1998–2000, so for these years the 2001 year value is set.

Equivalent robustness checks of the baseline 2SLS specification show that also these results are robust to the inclusion of controls. The results are available upon request.

The main reason for analyzing this sector grant is data availability. One may also argue that it is a relevant sector for this purpose, as educational spending is a quite flexible policy variable.

The full sample mean (standard deviation) of per capita educational spending and grants to education are 582.2 (144.8) and 174.0 (184.6), respectively.

Note that rather than analyzing conditional correlations, the causal effect of generic grants on educational spending can be estimated by running the original Eqs. (2) and (3) from above on Y educ. This yields statistically insignificant and quite small estimates—i.e., similar to the second row of Table 9 (the results are available upon request).

The Center Party has traditionally been large in rural areas, where many of the treated municipalities are located.

Center i =1 in about 80 % of the treated municipalities and in about 35 % of the control municipalities.

References

Athey, S., & Imbens, G. (2006). Identification and inference in nonlinear difference-in-differences models. Econometrica, 74, 431–497.

Bailey, S., & Connolly, S. (1998). The flypaper effect: identifying areas for further research. Public Choice, 95, 335–361.

Becker, E. (1996). The illusion of fiscal illusion: unsticking the flypaper effect. Public Choice, 86, 85–102.

Bradford, D., & Oates, W. (1971). The analysis of revenue sharing in a new approach to collective fiscal decisions. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 85, 416–439.

Brollo, F., & Nannicini, T. (2012). Tying your enemy’s hands in close races: the politics of federal transfers in Brazil. American Political Science Review, 106.

Brooks, L. (2008). Volunteering to be taxed: business improvement districts and the extra-governmental provision of public safety. Journal of Public Economics, 92, 388–406.

Dahlberg, M., Mörk, E., Rattsø, J., & Ågren, H. (2008). Using a discontinuous grant rule to identify the effect of grants on local taxes and spending. Journal of Public Economics, 92, 2320–2335.

Evans, W., & Owens, E. (2007). COPS and crime. Journal of Public Economics, 91, 181–201.

Filimon, R., Romer, T., & Rosenthal, H. (1982). Asymmetric information and agenda control: the bases of monopoly power in public spending. Journal of Public Economics, 17, 51–70.

Gordon, N. (2004). Do federal grants boost school spending? Evidence from title I. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1771–1792.

Gramlich, E. (1977). A review of the theory of intergovernmental grants. In W. Oates (Ed.), The political economy of fiscal federalism, Lexington: Lexington Books.

Grossman, P. (1994). A political theory of intergovernmental grants. Public Choice, 78, 295–303.

Hahn, J., Todd, P., & Van der Klaauw, W. (2001). Identification and estimation of treatment effects with a regression-discontinuity design. Econometrica, 69, 201–209.

Hamilton, J. (1986). The flypaper effect and the deadweight loss from taxation. Journal of Urban Economics, 19, 148–155.

Hines, J. Jr, & Thaler, R. (1995). Anomalies: the flypaper effect. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9, 217–226.

Inman, R. (2008). The flypaper effect. Working Paper 14579, NBER.

Knight, B. (2002). Endogenous federal grants and crowd-out of state government spending: theory and evidence from the federal highway aid program. The American Economic Review, 92, 71–92.

Levitt, S., & Snyder, J. Jr (1995). Political parties and the distribution of federal outlays. American Journal of Political Science, 958–980.

Litschig, S. (2012). Financing local development: quasi-experimental evidence from municipalities in Brazil, 1980–1991. Economics and Business Working Papers Series 1142, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Departament d’Economia i Empresa.

Lutz, B. (2010). Taxation with representation: intergovernmental grants in a plebiscite democracy. Review of Economics and Statistics, 92, 316–332.

Moisio, A. (2002). Essays on Finnish municipal finance and intergovernmental grants. PhD thesis, Government Institute for Economic Research (VATT), Helsinki.

Oulasvirta, L. (1997). Real and perceived effects of changing the grant system from specific to general grants. Public Choice, 91, 397–416.

Singhal, M. (2008). Special interest groups and the allocation of public funds. Journal of Public Economics, 92, 548–564.

Solé-Ollé, A., & Sorribas-Navarro, P. (2008). The effects of partisan alignment on the allocation of intergovernmental transfers: differences-in-differences estimates for Spain. Journal of Public Economics, 92, 2302–2319.

Thaler, R. (1985). Mental accounting and consumer choice. Marketing Science, 4, 199–214.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1984). Choices, values, and frames. The American Psychologist, 39, 341–350.

Van der Klaauw, W. (2002). Estimating the effect of financial aid offers on college enrollment: A regression-discontinuity approach. International Economic Review, 1249–1287.

Acknowledgements

This paper has benefited considerably from comments from Sören Blomquist, Matz Dahlberg, Mikael Elinder, Jon Fiva, Olle Folke, Eva Mörk, Tuomas Pekkarinen and Jørn Rattsø, as well as from the suggestions of two anonymous referees. I also thank participants at the 66th annual congress of the IIPF, at the public economics seminar in Uppsala, at the NTNU department seminar in Trondheim, at the 1st National Conference of Swedish Economists in Lund and in the “Topics in Applied Econometrics” course held in Aarhus February 2010 for valuable comments. Many thanks to Antti Moisio who provided data and other invaluable information. Financial support from Handelsbanken’s Research Foundation is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A: Other policies implemented in 2002

In this appendix, policies implemented in 2002 other than the one that increased the supplemental grant to remotely populated municipalities are reviewed. This is by no means a complete description of all implementations, but rather the attention is restricted to what is related to the specific policy reform studied in the paper. Specifically, for identification purposes, the simultaneous implementations require that treated and control municipalities were on average equally affected by these other policies. Fortunately—as is done in Sect. 4.1—most of this can be tested.

The policy reform that increased the supplemental grant to remotely populated municipalities is proposed in Government Bill 128/2001 and legislated in Law 1360/2001. These documents are also concerned with the following changes and reforms:

-

There was a change in the amount of the grant supplement to archipelago municipalities. According to law 494/1981, the development of a group of municipalities located in the archipelago is to be promoted. Before (after) 2002, such municipalities where at least 50 % of the population lacked access to a solid connection to the mainland got a per capita supplement equal to 3 (6) times the base grant, and those where less than 50 % lacked access to a solid connection to the mainland got a per capita supplement equal to 1.5 (3) times the base grant. In addition, municipalities not belonging to this particular group but that also had some share of their population in the archipelago got a supplement equal to 0.75 (1.5) times the base grant for each person living in the archipelago before (after) 2002. In the sample used in the paper, 41 municipalities received the archipelago supplement, all of which are in the control group. Neither excluding these 41 municipalities from the estimations nor controlling for the archipelago supplement affects the presented results.

-

In the revenue-sharing system, municipalities with potential per capita tax revenues (revenues when applying a weighted average of the tax rates) above average pay a fee equal to 40 % of the difference. Before 2002, this fee could be at most 15 % of the municipality’s total per capita potential tax revenues, but in 2002 this cap was removed. This affected 4 municipalities, all in the control group. Excluding them from the estimations does not affect the results presented in the paper.

-

Municipalities that were highly affected by the introduction of the new grant system in 1997 got transitory grants that were gradually decreased between 1997 and 2001 and were entirely removed in 2002. This removal considerably affected the group of the 13 most remotely populated municipalities, which is why they are removed from the empirical analysis. Note also that the results presented in the paper when controlling for transitory grants to the remaining municipalities are similar to the baseline results.

-

Some of the activities in the local government sector are directly financed by the state to an extent that may vary over time, in which case there is an adjustment through the sector grants (grants to social services and health care and grants to education and culture). An adjustment due to increased relative financing responsibility on behalf of the municipalities in 2000 was originally to be implemented with 50 % in 2001 and with 25 % each in 2002 and 2003. However, it was decided that the full remaining 50 % were to be implemented in 2002, implying that the increase in the sector grants was brought forward to 2002 from 2003. There were also some additional changes to the sector grants; see below.

One of the more significant reforms in 2002 aiming at stabilizing local government finances was a change in the administration of value added taxes (VAT), described in Government Bill 130/2001 and legislated in Laws 1456-1457/2001. When the municipalities’ activities involve goods with VAT, they (like firms) are entitled to deductions. Prior to 2002, the municipalities had to repay these deductions to the state with an equal per capita amount. Since the amount of deductions varied considerably across regions but the repayments were the same, this made it difficult to keep stable finances and thus the repayments were abolished. Consequently, this shifted the fiscal balance in favor of the municipalities at the expense of the state.

The main reform to re-balance the fiscal relation was a decrease in the municipalities’ share of revenue—and thereby an increase in the state’s share—from corporate income taxation (also proposed in 130/2001 and legislated in Laws 1458-1459/2001). Part of the motivation was that this type of revenue was highly sensitive to economic fluctuations and was very unevenly distributed across municipalities depending on business locations. The municipalities’ share was therefore decreased from 37.25 to 24.09 %. Note that the results presented in the paper when controlling for corporate tax revenues are similar to the baseline results.

Finally, partly as a consequence of some of the previously described reforms, there were some changes to the sector grants (proposed in Government Bill 132/2001 and legislated in Law 1389/2001 for education and culture, and proposed in Government Bill 152/2001 and legislated in Law 1409/2001 for social services and health care). As previously mentioned, these grants were increased in order to adjust for the altered fiscal responsibilities between the state and the municipalities. It was additionally decided that the increase in the state’s revenue due to the removal of the 15 % cap in the revenue sharing system was to be transferred to the municipalities as increased grants to social services and health care. On the other hand, the reform in the VAT system implied decreased sector grants. All in all, the majority of municipalities received more sector grants in 2002 than in 2001. Note that the results presented in the paper when controlling for total grants received are similar to the baseline results.

Appendix B: Derivation of Eq. (6)

In this appendix, the RD model in Eq. (6) is derived.

There are two points of the remote index at which the grant increase jumps discontinuously; at 0.50 and at 1. Let \(D_{i}^{1}\) be a dummy that equals 1 if municipality i belongs to group 1 and thus has a remote index in the interval 0.50–1, and 0 otherwise. Similarly, let \(D_{i}^{2}\) be a dummy that equals 1 if municipality i belongs to group 2 and thus has a remote index in the interval 1–1.50, and 0 otherwise. Then, in the following model:

the parameters \(\tilde{\tau}^{1}\) and \(\tilde{\tau}^{2}\) identify the effect on the outcome ΔY i due to the discontinuous increase in the supplemental grant at remote index 0.50 and at remote index 1, respectively.

In order to evaluate the treatment effects in euro per capita grant increases, multiply the indicators \(D_{i}^{1}\) and \(D_{i}^{2}\) with the amount of the supplemental grant increase, ΔSG i :

Note that ΔSG i is constant within the two groups, so that τ 1 and τ 2 only are rescaled versions of their \(\tilde{\tau}^{1}\) and \(\tilde{\tau}^{2}\) counterparts.

Finally, restrict the treatment effect to be the same at the 0.50 discontinuity as at the 1 discontinuity. That is, assume τ 1=τ 2=τ, and arrive at

where the D i ’s have been removed, as they are simply indicators for ΔSG i ≠0.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lundqvist, H. Granting public or private consumption? Effects of grants on local public spending and income taxes. Int Tax Public Finance 22, 41–72 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-013-9279-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-013-9279-7