Abstract

Is inequality within countries relevant for global climate policy? Most burden-sharing proposals for climate mitigation treat states as homogenous agents, even those that aim to protect individual rights. This can lead to free riders in some large emerging economies and expose the poor to mitigation burdens in others. Proposals that incorporate an exemption for the poor can avoid these outcomes, but do not account for the role of internal policies on the poor’s actual emissions and mitigation burdens. This will create moral hazards in the design of such agreements and risk the misallocation of mitigation costs when implemented. To ensure equitable outcomes at the individual level, international agreements would need to build in additional provisions to encourage benefiting states to reduce emissions and target exemptions to the poor. But such agreements will face political conflicts over sovereignty and the burdensomeness of such provisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

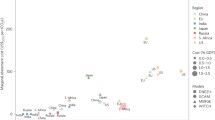

Data from the Climate Analysis Indicators Tool (CAIT) of the World Resources Institute.

Poverty data from the World Bank development indicators.

China Statistical Yearbook (2009) indicates that every 100 urban households in China own 133 color TVs, 100 air conditioners, 94 refrigerators, 59 computers, and 55 microwaves.

The estimates are based on a lognormal distribution of income. See Sect. 4. India’s estimate uses a GDP growth rate of 7% (which was India’s average rate between 2000 and 2010) and a Gini coefficient of 0.37, reducing to 0.42 (about the rate, it increased from 2000 to 2010) by 2020.

The estimate is based on a Gini coefficient of 0.59 for Brazil in 2006, from the World Development Indicators.

This estimate is based on a Gini coefficient of 0.45 for China in 2006, from the World Development Indicators.

Note that the choice of metric—emissions or income—can have a significant impact on countries’ mitigation obligations. The two are not necessarily correlated. This issue is not material here, because the arguments pertain to the notion of a threshold, regardless of how it is operationalized.

World Bank Poverty database.

Other types of uncertainty that matter for monitoring and verification, but are not addressed here, include the validity of metrics, the accuracy of data, and of future predictions. See Page (2008) for some discussion on this.

This is the approach used in Greenhouse Development Rights (Baer et al. 2008).

The low GDP growth rate is the average growth rate in the previous two decades, while the high represents the “aspirational” growth rate in government projections. See (Ministry of Environment and Forests; Government of India 2009). The chosen increase/decrease for the Gini coefficient closely matches the actual increase (~.33 to ~.37) from 2000 to 2007, according to World Development Indicators, World Bank. The high population growth rate represents the highest rate between 2000 and 2009. The same gap between the BAU and high was applied to yield the low rate.

The financial impact of uncertainty does not vary proportionately with changes in the threshold itself. Indeed, the elasticity of poverty to growth and inequality may depend on the chosen threshold. The larger the gap between the exemption threshold and average income (as is the case with the US poverty line), the less elastic is poverty reduction to changes in growth and inequality.

A classic example is of the putatively “negative cost” energy efficiency measures that economists often cite but that continue to remain unexploited. See McKinsey Global GHG Abatement Cost Curve, Project Catalyst, 2009. http://www.project-catalyst.info.

IPCC, Sustainable Development, Working Group III Contribution to the Fourth Assessment Report: 12.

In Pogge’s view, an institution (in this case, the mitigation agreement) may be implicated even if it causes harm through the actions of another institution (i.e., the benefiting state).

The Doha Declaration, paragraph 7.

“China and U.S. Hit Strident Impasse at Climate Talks,” New York Times, December 14, 2009.

Abbreviations

- BASIC:

-

Brazil, South Africa, India, and China

- BAU:

-

Business as usual

- CDM:

-

Clean Development Mechanism

- GDR:

-

Greenhouse Development Rights

- GDP:

-

Gross domestic product

- IPCC:

-

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

- NAMA:

-

Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Action

- PPP:

-

Purchasing power parity

- REDD:

-

Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation

- TRIPS:

-

Trade-related aspects of Intellectual Property Rights

- WTO:

-

World Trade Organization

References

Agarwal, A., & Narain, S. (1991). Green politics: Global environmental negotiations. New Delhi, India: Center for Science and Environment.

Baer, P., Athanasiou, T., Kartha, S., & Kemp-Benedict, E. (2008). The Greenhouse development rights framework: The right to development in a climate Constrained world. Heinrich Boll Foundation, EcoEquity, Christian Aid (Ed.). Berlin.

Caney, S. (2009a). Climate change, human rights, and moral thresholds. In S. Humphreys & Mary. Robinson (Eds.), Human rights and climate change. Oxford: Cambridge University Press.

Caney, S. (2009b). Justice and the distribution of greenhouse gas emissions. Journal of Global Ethics, 5(2), 125–146.

Caney, S. (2010). Climate change and the duties of the advantaged. Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 13(1), 203–228.

Chakravarty, S., Chikkatur, A., de Coninck, H., Pacala, S., Socolow, R., & Tavoni, M. (2009). Sharing global CO2 emission reductions among one billion high emitters. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(29), 11884–11888.

Chen, J. R., & Sapsford, D. (Eds.). (2005). Global development and poverty reduction: The challenge for international institutions (International institutions and global governance). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Clapp, J., & Wilkinson, R. (Eds.). (2010). Global governance, poverty and inequality (Global institutions). New York: Routledge.

Claussen, E., & McNeilly, L. (1998). Equity & global climate change: The Complex elements of global fairness. Washington, D.C.: Pew Center on Global Climate Change

Conca, K. (1994). Rethinking the ecology-sovereignty debate. Millennium—Journal of International Studies, 23(3), 701–711.

den Elzen, M., & Höhne, N. (2008). Reductions of greenhouse gas emissions in Annex I and non-Annex I countries for meeting concentration stabilisation targets. Climatic Change, 91(3), 249–274.

Diringer, E. (2011). Climate policy: Letting go of Kyoto. Nature, 479(7373), 291–292.

Frankel, J. (2007). Formulas for quantitative emissions targets. In J. E. Aldy & R. N. Stavins (Eds.), Architectures for agreement: Addressing global climate change in the post-kyoto world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gardiner, S. (2004). Ethics and global climate change. Ethics, 114, 555–600.

Gardiner, S., Caney, S., Jamieson, D., & Shue, H. (2010). Climate ethics: Essential readings. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gordon, R. H., & Li, W. (2005). Tax structure in developing countries: Many puzzles and a possible explanation. NBER working papers 11267, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Grasso, M. (2007). A normative ethical framework in climate change. Climatic Change, 81(3), 223–246.

Haas, P. M., Keohane, R. O., & Levy, M. A. (1993). Institutions for the earth: Sources of effective international environmental protection. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Herring, R. J. (1999). International justice, poverty and the environment. Paper presented at the values, norms and poverty: A consultation on the world development report 2001, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Jamieson, D. (2001). Climate change and global environmental justice. In P. Edwards & C. Miller (Eds.), Changing the atmosphere: Expert knowledge and global environmental governance. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Jiahua, P., Chen, Y., Wang, W., & Li, C. (2008). Carbon budget proposal, global emissions under carbon budget constraint on an individual basis for an equitable and sustainable post 2012 international climate regime. Beijing: Research Centre for Sustainable Development, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

Kanitkar, T., Jayaraman, T., D’Souza, M., Sanwal, M., Purkayastha, P., & Talwar, R. (2009). Meeting equity in a finite carbon world: Global carbon budgets and burden sharing in mitigation actions. Paper presented at the global carbon budgets and equity in climate change, Mumbai, June 28–29, 2010.

Kant, P., Chaliha, S., & Shuirong, W. (2011). The REDD safeguards of cancun. New Delhi: Institute of Green Economy.

Klinsky, S., & Dowlatabadi, H. (2009). Conceptualizations of justice in climate policy. Climate Policy, 9, 88–108.

Komives, K., Foster, V., Halpern, J., & Wodon, Q. (2005). Water, electricity, and the poor: Who benefits from utility subsidies?. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Litfin, K. T. (1997). Sovereignty in world ecopolitics. Mershon International Studies Review, 41(2), 167–204.

Lopez, J. H., & Servén, L. (2006). A Normal relationship? Poverty, growth and inequality. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

McKinsey and Company (2009). Environmental and energy sustainability: An approach for India. Magnum Custom Publishing, New Delhi.

Milanovic, B. (2007). Global income inequality: What it is and why it matters. In K. S. Jomo & J. Baudot (Eds.), Flat world, big gaps: Economic liberalization, globalization, poverty & inequality. New York: United Nations Publications.

Ministry of Environment and Forests; Government of India. (2009). India’s GHG emissions profile: Results of five climate modelling studies. Climate Modelling Forum. Available at: http://www.envfor.nic.in/mef/GHG_report.pdf

Müller, B., Höhne, N., & Ellermann, C. (2009). Differentiating (historic) responsibilities for climate change. Climate Policy, 9, 593–611.

Palma, J. G. (2007). Globalizing inequality: ‘Centrifugal’ and ‘centripetal’ forces at work. In K. S. Jomo & J. Baudot (Eds.), Flat world, big gaps: economic liberalization, globalization, poverty & inequality (p. 102). New York: United Nations Publications.

Peters, G. P., Andrew, R. M., Boden, T., Canadell, J. G., Ciais, P., Le Quere, C., et al. (2013). The challenge to keep global warming below 2 [deg] C. Nature Climate Change, 3(1), 4–6.

Piketty, T., & Qian, N. (2009). Income inequality and progressive income taxation in China and India, 1986–2015. Applied Economics, 1(2), 53–63.

Pogge, T. (2005). Severe poverty as a violation of negative duties. Ethics & International Affairs, 19(1), 55–83.

Rajamani, L. (2012). The Durban platform for enhanced action and the future of the climate regime. International & Comparative Law Quarterly, 61(02), 501–518.

Rao, N. D. (2012). Kerosene subsidies in India: When energy policy fails as social policy. Energy for Sustainable Development, 16(1), 35–43.

Ravallion, M. (2009). The developing world’s bulging (but vulnerable) ‘middle class’: Policy Research Working Paper 4816, World bank, Washington, D.C.

Ravallion, M., & Datt, G. (2002). Why has economic growth been more pro-poor in some states of India than others? Journal of Development Economics, 68, 381–400.

Ringius, L., Torvanger, A., & Underdal, A. (2002). Burden sharing and fairness principles in international climate policy. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 2(1), 1–22.

Shue, H. (1993). Subsistence emissions and luxury emissions. Law and Policy, 15, 39–59.

Shue, H. (1999). Global environment and international inequality. International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-), 75(3), 531–545.

Singer, P. (2002). One world: Ethics of globalization. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Sutcliffe, B. (2004). World inequality and globalization. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 20(1), 15–37.

Vanderheiden, S. (2009). Atmospheric justice: A political theory of climate change. New York: Oxford University Press.

Victor, D. (2007). Fragmented carbon markets and reluctant nations: implications for the design of effective architectures. In J. Aldy (Ed.), Architectures for agreement: Addressing global climate change in the post-kyoto world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

WBGU (2009). Solving the climate dilemma: The budget approach. Special report, German advisory council on global change, Berlin.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Joshua Cohen, Debra Satz, David Victor, and Larry Goulder for their invaluable guidance. I also thank Paul Baer and anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rao, N.D. International and intranational equity in sharing climate change mitigation burdens. Int Environ Agreements 14, 129–146 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-013-9212-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-013-9212-7