Abstract

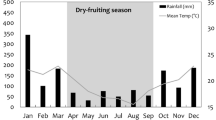

Understanding how primates adjust their behavior in response to seasonality in both continuous and fragmented forests is a fundamental challenge for primatologists and conservation biologists. During a 15-mo period, we studied the activity patterns of 6 communities of spider monkeys (Ateles geoffroyi) living in continuous and fragmented forests in the Lacandona rain forest, Mexico. We tested the effects of forest type (continuous and fragmented), season (dry and rainy), and their interaction on spider monkey activity patterns. Overall, monkeys spent more time feeding and less time traveling in fragments than in continuous forest. A more leafy diet and the spatial limitations in fragments likely explain these results. Time spent feeding was greater in the rainy than in the dry season, whereas time spent resting followed the opposite pattern. The increase in percent leaves consumed, and higher temperatures during the dry season, may contribute to the observed increase in resting time because monkeys probably need to reduce energy expenditure. Forest type and seasonality did not interact with activity patterns, indicating that the effect of seasonality on activities was similar across all sites. Our findings confirm that spider monkeys are able to adjust their activity patterns to deal with food scarcity in forest fragments and during the dry season. However, further studies are necessary to assess if these shifts are adequate to ensure their health, fitness, and long-term persistence in fragmented habitats.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Altmann, J. (1974). Observational study of behavior: Sampling methods. Behavior, 49, 227–267.

Arroyo-Rodríguez, V., & Dias, P. A. (2010). Effects of habitat fragmentation and disturbance on howler monkeys: A review. American Journal of Primatology, 72, 1–16.

Arroyo-Rodríguez, V., & Mandujano, S. (2006). Forest fragmentation modifies habitat quality for Alouatta palliata. International Journal of Primatology, 27, 1079–1096.

Arroyo-Rodríguez, V., Mandujano, S., Benítez-Malvido, J., & Cuende-Fanton, C. (2007a). The influence of large tree density on howler monkey (Alouatta palliata mexicana) presence in very small rain forest fragments. Biotropica, 39, 760–766.

Arroyo-Rodriguez, V., Serio-Silva, J. C., Alamo-Garcia, J., & Ordano, M. (2007b). Exploring immature-to-mother social distances in Mexican mantled howler monkeys at Los Tuxtlas, Mexico. American Journal of Primatology, 69, 163–181.

Asensio, N., Korstjens, A. H., & Aureli, F. (2009). Fissioning minimizes ranging costs in spider monkeys: A multiple-level approach. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 63, 649–659.

Bicca-Marques, J. C. (2003). How do howler monkeys cope with habitat fragmentation? In L. K. Marsh (Ed.), Primates in fragments: Ecology and conservation (pp. 283–303). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Press.

Boyle, S. A., & Smith, A. T. (2010). Behavioral modifications in northern bearded saki monkeys (Chiropotes satanas chiropotes) in forest fragments of central Amazonia. Primates, 51, 43–51.

Boyle, S. A., Lourenco, W. C., da Silva, L. R., & Smith, A. T. (2009). Travel and spatial patterns change when Chiropotes satanas chiropotes inhabit forest fragments. International Journal of Primatology, 30, 515–531.

Bronikowski, A. M., & Altmann, J. (1996). Foraging in a variable environment: weather patterns and the behavioral ecology of baboons. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 39, 11–25.

Campos, F. A., & Fedigan, L. M. (2009). Behavioral adaptations to heat stress and water scarcity in white-faced capuchins (Cebus capucinus) in Santa Rosa National Park, Costa Rica. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 138, 101–111.

Chapman, C. A. (1988). Patterns of foraging and range use by three species of Neotropical primates. Primates, 29, 177–194.

Chapman, C. A., & Chapman, L. J. (1991). The foraging itinerary of spider monkeys: When to eat leaves? Folia Primatologica, 56, 162–166.

Chapman, C. A., & Chapman, L. J. (2000). Determinants of group size in primates: The importance of travel costs. In S. Boinski & P. A. Garber (Eds.), On the move: How and why animals travel in groups (pp. 24–42). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Chapman, C. A., Naughton-Treves, L., Lawes, M. J., Wasserman, M. D., & Gillespie, T. R. (2007). Population declines of colobus in Western Uganda and conservation value of forest fragments. International Journal of Primatology, 28, 513–528.

Chaves, O. M., Stoner, K. E., & Arroyo-Rodríguez, V. (2011). Differences in diet between spider monkey groups living in forest fragments and continuous forest in Lacandona, Mexico. Biotropica, doi:10.1111/j.1744-7429.2011.00766.x.

Clarke, M. R., Collins, A. D., & Zucker, E. L. (2002). Responses to deforestation in a group of mantled howlers (Alouatta palliata) in Costa Rica. International Journal of Primatology, 23, 365–381.

Crawley, M. (2002). Statistical computing: An introduction to data analysis using S-Plus. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Cristóbal-Azkarate, J., & Arroyo-Rodríguez, V. (2007). Diet and activity pattern of howler monkeys (Alouatta palliata) in Los Tuxtlas, Mexico: Effects of habitat fragmentation and implications for conservation. American Journal of Primatology, 69, 1013–1029.

De la Maza, J., & De la Maza. R. (1991). El ‘Monte Alto’: Esbozo de una región. In Agrupación Sierra Madre, Lacandonia, el último refugio (pp. 21–35). Distrito Federal, México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Defler, T. R. (1995). The time budget of a group of wild woolly monkeys (Lagothrix Lagotricha). International Journal of Primatology, 16, 107–120.

Di Fiore, A., Link, A., & Dew, J. L. (2008). Diets of wild spider monkeys. In C. J. Campbell (Ed.), Spider monkeys: Behavior, ecology and evolution of the genus Ateles (pp. 81–137). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Di Fiore, A., Link, A., & Campbell, C. J. (2010). The atelines: Behavioral and socioecological diversity in a New World radiation. In C. J. Campbell, A. Fuentes, K. C. Mackinnon, M. Panger, & S. K. Bearder (Eds.), Primates in perspective (pp. 784–798). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dunbar, R. I. M. (1992). Time: A hidden constraint on the behavioural ecology of baboons. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 31, 35–49.

Dunbar, R. I. M., Korstjens, A. H., & Lehmann, J. (2009). Time as an ecological constraint. Biological Reviews, 84, 413–429.

Dunn, J. C., Cristóbal-Azkarate, J. C., & Vea, J. (2010). Seasonal variations in the diet and feeding effort of two groups of howler monkeys in different sized forest fragments. International Journal of Primatology, 31, 887–903.

Felton, A. M., Felton, A., Wood, J. F., Foley, W. J., Raubenheimer, D., Wallis, I. R., et al. (2009). Nutritional ecology of Ateles chamek in lowland Bolivia: How macronutrient balancing influences food choices. International Journal of Primatology, 30, 675–696.

Gentry, A. H. (1982). Patterns of neotropical plant species diversity. Evolutionary Biology, 15, 1–84.

Gómez-Pompa, A., & Dirzo, R. (1995). Atlas de las áreas naturales protegidas de México. Distrito Federal, México: CONABIO-INE.

González-Di Pierro, A. M., Benítez-Malvido, J., Méndez-Toribio, M., Zermeño, I., Arroyo-Rodríguez, V., & Stoner, K. E. (2011). Effects of the physical environment and primate gut passage on the early establishment of Ampelocera hottlei Standley in rainforest fragments. Biotropica, doi:10.1111/j.1744-7429.2010.00734.x.

González-Zamora, A., Arroyo-Rodríguez, V., Chaves, O. M., Sánchez-López, S., & Stoner, K. E. (in review). Influence of climatic variables, forest type and condition on activity patterns of Geoffroyi´s spider monkeys throughout Mesoamerica. American Journal of Primatology.

González-Zamora, A., Arroyo-Rodríguez, V., Chaves, O. M., Sánchez-López, S., Stoner, K. E., & Riba-Hernández, P. (2009). Diet of spider monkeys (Ateles geoffroyi) in Mesoamerica: Current knowledge and future directions. American Journal of Primatology, 71, 8–20.

Hemingway, C. A., & Bynum, N. (2005). The influence of seasonality on primate diet and ranging. In D. K. Brockman & C. P. van Schaick (Eds.), Seasonality in primates: Studies of living and extinct human and non-human primates (pp. 57–104). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Irwin, M. T. (2008a). Diademed sifaka (Propithecus diadema) ranging and habitat use in continuous and fragmented forest: Higher density but lower viability in fragments? Biotropica, 40, 231–240.

Irwin, M. T. (2008b). Feeding ecology of Propithecus diadema in forest fragments and continuous forest. International Journal of Primatology, 29, 95–115.

Iwamoto, T., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (1983). Thermoregulation, habitat quality and the behavioural ecology in gelada baboons. The Journal of Animal Ecology, 53, 357–366.

Juan, S., Estrada, A., & Coates-Estrada, R. (2000). Contrastes y similitudes en el uso de recursos y patrón general de actividades en tropas de monos aulladores (Alouatta palliata) en fragmentos de selva de Los Tuxtlas, México. Neotropical Primates, 8, 131–135.

Korstjens, A. H., Verhoeckx, I. L., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (2006). Time as a constraint on group size in spider monkeys. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 60, 683–694.

Korstjens, A. H., Lehman, J., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (2010). Resting time as an ecological constraint on primate biogeography. Animal Behaviour, 79, 361–374.

Lambert, J. E. (1998). Primate digestion: Interactions among anatomy, physiology, and feeding ecology. Evolutionary Anthropology, 7, 8–20.

Laurance, W. F., Laurance, S. G., Ferreira, L. V., Rankin-de Merona, J. M., Gascon, C., & Lovejoy, T. E. (1997). Biomass collapse in Amazonian forest fragments. Science, 278, 1117–1118.

López, G. O., Terborgh, J., & Ceballos, N. (2005). Food selection by a hyperdense population of red howler monkeys (Alouatta seniculus). Journal of Tropical Ecology, 21, 445–450.

Marquez-Rosano, C. (2006). Environmental policy and dynamics of territorial appropriation: The tensions between the conservation of tropical forests and the expansion of cattle ranching in the Mexican tropics. Retrieved from http://iasc2008.glos.ac.uk/conference%20papers/papers/M/Marquez-Rosano_110701.pdf.

Masi, S., Cipolletta, C., & Robbins, M. M. (2009). Western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) change their activity patterns in response to frugivory. American Journal of Primatology, 71, 91–100.

Milton, K. (1981a). Food choice and digestive strategies of two sympatric primate species. The American Naturalist, 117, 476–495.

Milton, K. (1981b). Distribution patterns of tropical plant foods as an evolutionary stimulus to primate mental development. American Anthropologist, 83, 534–548.

Murphy, P., & Lugo, A. E. (1995). Dry forests of Central America and the Caribbean. In S. H. Bullock, H. M. Mooney, & E. Medina (Eds.), Seasonally dry tropical forests (pp. 146–194). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Onderdonk, D. A., & Chapman, C. A. (2000). Coping with forest fragmentation: The primates of Kibale National Park, Uganda. International Journal of Primatology, 21, 587–611.

Overdorff, D. J. (1996). Ecological correlates to activity and habitat use of two prosimian primates: Eulemur rubriventer and Eulemur fulvus rufus in Madagascar. American Journal of Primatology, 40, 327–342.

Rebecchini, L., Schaffner, C. M., Auleri, F., Vick, L., & Ramos-Fernández, G. (2008). The impact of hurricane Emily on the activity budget, diet and subgroup composition of wild spider monkeys (Ateles geoffroyi yucatanensis). In 22nd Congress of the International Primatological Society, Abstract Book, p. 147.

Silva, S. S. B., & Ferrari, S. F. (2009). Behavior patterns of southern bearded sakis (Chiropotes satanas) in the fragmented landscape of eastern Brazilian Amazonia. American Journal of Primatology, 71, 1–7.

Stelzner, J. K. (1988). Thermal effects on movement patterns of yellow baboons. Primates, 29, 91–105.

Stevenson, P. R. (2001). The relationship between fruit production and primate abundance in Neotropical communities. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 72, 161–178.

Stevenson, P. R., Quiñones, M. J., & Ahumada, J. A. (1994). Ecological strategies of woolly monkeys (Lagothrix lagotricha) at Tinigua National Park, Colombia. American Journal of Primatology, 32, 123–140.

Stoner, K. E., & Timm, R. M. (2004). Tropical dry-forest mammals of Palo Verde: Ecology and conservation in a changing landscape. In G. W. Frankie, A. Mata, & S. B. Vinson (Eds.), Biodiversity conservation in Costa Rica: Learning the lessons in a seasonal dry forest (pp. 48–66). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Tutin, C. E. (1999). Fragmented living: Behavioural ecology of primates in a forest fragment in Lopé Reserve, Gabon. Primates, 40, 249–265.

Wallace, R. B. (2001). Diurnal activity budgets of black monkeys, Ateles chamek, in a southern Amazonian tropical forest. Neotropical Primates, 9, 101–107.

Watts, C. H. (1988). Environmental influences on mountain gorilla time budgets. American Journal of Primatology, 15, 195–211.

Zimmerman, J. K., Wright, S. J., Calderon, O., Pagan, M. A., & Paton, S. (2007). Flowering and fruiting phenologies of seasonal and aseasonal Neotropical forests: The role of annual changes in irradiance. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 23, 231–251.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT grants CB2005-C01-51043 and CB2006-56799). Ó. M. Chaves obtained a scholarship from the Dirección General de Estudios de Posgrado, UNAM, as part of the Programa de Posgrado en Ciencias Biológicas and from Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores (SRE) of Mexico. A postdoctoral fellowship awarded to V. Arroyo-Rodríguez by the Consejo Técnico de la Investigación Científica (UNAM) is gratefully acknowledged. The Instituto para la Conservación y el Desarrollo Sostenible, Costa Rica (INCODESO) provided logistical support. This study would not have been possible without the collaboration of the local people in Loma Bonita, Chajul, Reforma Agraria, and Zamora Pico de Oro Ejidos. We thank C. Hauglustaine, C. Balderas, K. Amato, S. Martínez, J. Herrera, and R. Lombera for field assistance. A. Estrada and J. Benítez-Malvido made useful suggestions during the design of this research. J. M. Lobato, G. Sánchez, H. Ferreira, and A. Palencia provided technical support. We also thank J. Rothman, J. Setchell, and 2 anonymous reviewers for valuable criticisms and suggestions that improved the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Table SI

Importance value index (IVI) of the top food species for spider monkeys in the three study forest fragments within the Marqués de Comillas region, Lacandona, Chiapas, Mexico (DOC 55.0 kb)

Table SII

Values of the general linear model either excluding or including the larger fragment inhabited by the spider monkeys in Lacandona, Southern Mexico (DOC 36.5 kb)

Fig. S1

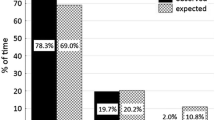

Percent of focal observations discarded in each forest type according to the activity pattern. The number of discarded observations is indicated above the bars (DOC 27.5 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chaves, Ó.M., Stoner, K.E. & Arroyo-Rodríguez, V. Seasonal Differences in Activity Patterns of Geoffroyi´s Spider Monkeys (Ateles geoffroyi) Living in Continuous and Fragmented Forests in Southern Mexico. Int J Primatol 32, 960–973 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-011-9515-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-011-9515-x