Abstract

The clam Rangia cuneata, originating from the Gulf of Mexico, was recorded in the Vistula Lagoon for the first time in the early 2010s, and quickly became the dominant component of the zoobenthic biomass. To assess mortality as a factor potentially controlling the growth of Rangia population, a year-long field experiment involving marked bivalves placed in sediment-filled trays deployed on the bottom was conducted in 2014 and 2015. Predator-induced mortality of the clams was low in summer, and very high in the winter–spring period. It was inversely proportional to the size of the clams. Such changes can be partially attributed to predation from at least five fish and three duck species, which contained clams in their digestive tracts. Non-predatory mortality particularly affected large individuals, and was highest in spring, several weeks after the end of winter. We hypothesize that it could be caused by persistent low temperatures over several winter months which led to considerable weakening of the condition of clams. A long winter could also reduce their resistance to environmental stress and potential effect of epibionts, as well as increase susceptibility to predation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Invasive alien species are an increasingly serious ecological and socio-economic issue worldwide (Williamson & Fitter, 1996; Sala et al., 2000; Katsanevakis et al., 2014), although positive impacts do exist (e.g., Charles & Dukes, 2007). The determination of when, where, and why mortality occurs within the inter- and intra-annual cycles is important for understanding the invader population dynamics and ecosystem functioning. This knowledge may be useful in formulating plans to reduce the negative impact of invaders. However, research on factors that affect mortality of non-indigenous species in a natural environment is very difficult to perform. This particularly applies to aquatic species, including molluscs. Consequently, such reports are scarce (Robinson & Wellborn, 1988; Reusch, 1998; Hill & Lodge, 1999; Strayer, 1999; Byers, 2002a; Carlsson et al., 2011; Sousa et al., 2014). This scarcity of research also applies to the clam Rangia cuneata (G. B. Sowerby I), a species native to the Gulf of Mexico, where it lives in estuaries at salinities below 19 PSU (LaSalle & de la Cruz, 1985). In Europe, it was first found in Antwerp harbour, Belgium, in 2005 (Verween et al., 2006). Since then, it has been recorded in several other countries, including Poland (Möller & Kotta, 2017). Such a fast rate of colonisation is typical of r-strategists, including R. cuneata, considering features of the species such as its short life span, small size, high fecundity, feeding flexibility, and high resistance to unfavourable environmental conditions (LaSalle & de la Cruz, 1985).

In the Vistula Lagoon, R. cuneata was recorded in the early 2010s (Rudinskaya & Gusev, 2012; Warzocha & Drgas, 2013). At present, clams reach abundances of up to 200 ind. m−2, dominating the zoobenthic biomass (Warzocha et al., 2016). The clam population fluctuates considerably, with strong reductions after long and harsh winters in some years. To highlight the reasons for such fluctuations, we performed year-long experimental field research with marked clams placed on trays filled with sediment which were deployed on the bottom of the lagoon. We analysed losses of clams caused by predators and non-predatory causes that could result from the influence of abiotic factors (e.g., water oxygenation and salinity, temperature). We also conducted preliminary analyses concerning the occurrence of parasites and epibionts on R. cuneata, whose effect on the host could influence the magnitude of both predatory and non-predatory mortality. Mortality was analysed as a function of both time and clam size. We expected increased clam losses due to predation pressure in summer, when ectothermal predators are most active, and increased mortality caused by abiotic factors in winter, as a result of harsh conditions. Moreover, considering the fact that R. cuneata represents an r-reproductive strategy, we assumed that the greatest losses from both types of factors would affect young, small clams. This study is the first to investigate the issue of survivorship of R. cuneata outside its natural range.

Study site and methods

The Vistula Lagoon is in the south-eastern part of the Baltic Sea. It is strongly elongated, SW–NE oriented, and large (838 km2) but shallow (mean depth 2.5 m; max. depth 5.2 m). The lagoon’s basin is separated from the Baltic Sea by the Vistula Spit in the north, and connected with the sea by the Baltiysk Strait. The area lacks regular tides. Water-level fluctuation with an amplitude of approximately 1 m is irregular owing to wind action. Concentrations of nutrients in the lagoon are high (Ntot. = 1.65–2.31 mg l−1; Ptot. = 0.089–0.114 mg l−1), favouring the development of phytoplankton which is dominated by cyanobacteria, including the potentially toxic Anabaena and Microcystis (Nawrocka & Kobos, 2011).

The littoral zone has an intermittent belt of reed Phragmites australis (Cav.), cattail Typha spp., or lakeshore bulrush Schoenoplectus lacustris (L.). Deeper, up to 1.5 m, the bottom is colonised by scattered patches of submerged vegetation, particularly by perfoliate pondweed Potamogeton perfoliatus L. and sago pondweed Stuckenia pectinata (L.).

The study was conducted between 5 June 2014 and 26 May 2015 at a depth of 1.7 m, at a distance of approximately 800 m from the shore (54°19.875′N, 19°31.958′E) (Fig. 1). The sediment at the experimental site was sandy, with a slight admixture of mud, with no submerged vegetation.

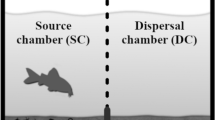

Experiment on survivorship/mortality of Rangia cuneata

The sediment was collected by means of multiple Ekman grabs and sieved through 3-mm mesh to remove clams, shell fragments, and large invertebrates. The same sediment was used in all trays to avoid a possible data distortion caused by varying sediment compositions. After mixing the sediment in a 90-l container, a 0.5-l sediment sample was collected for chemical and granulometric analyses. A 10-cm thick layer of sediment was placed in five numbered plastic trays (length: 49 cm; width: 37 cm; depth: 15 cm; surface area: 0.1813 m2). Then, the trays were randomly seeded with 20 clams to obtain a number equivalent to a density of 115 ind. m−2 (which was the mean value observed in the environment based on 20 samples collected randomly by means of an Ekman grab with a sampling area of 225 cm2). The clams used in the experiment had a mean length of 25 mm (range: 9–40 mm, SD standard deviation: ± 5.2). They were collected near the experimental site by means of a bottom dredge. The length of each individual was measured with a caliper with the accuracy of 0.1 mm. All clams were marked with a number on both sides of the shell with a water-proof oil marker. Data concerning each of the clams were entered into a form. This permitted tracing the history of each individual separately.

On 5 June 2014, the trays with the sediment and marked clams were submerged to the bottom, in random order parallel to the shore by lowering them carefully with a rope with the opposite end attached to marker buoys. The marker buoys indicated the position of each of the submerged trays and were removed after all the trays had been placed on the bottom. A detailed description of the experimental setup, its deployment, and retrieval is available in Kornijów et al. (2017). The trays were left for the following five periods: 5 June–21 July 2014, 22 July–3 September 2014, 4 September–16 October 2014, 17 October 2014–24 April 2015, and 25 April–26 May 2015. After each period, the trays were gently lifted from the lagoon bottom and recovered. In several cases, we recorded several cm changes in sediment level in the trays. They involved loss of sediment much more frequently than an increase in its level. In the latter case, the level of sediment always remained at least several cm below the upper edge of the trays. Because clams do not climb obstacles, but rather hide in sediments, chances for the clams to leave the trays were scarce. Due to a considerable thickness and weight of the shells, it was also improbable for them to be washed out of the trays as a result of strong wave action, which was confirmed by observations performed in the laboratory. Clams placed in Petri dishes with 2-cm high walls, half-filled with sediment and placed on the bottom of aquaria for several weeks, were not able to escape in spite of considerable water movement caused by an aerator, or by lifting and dropping the dishes.

After tray removal, the sediment was washed through a 3-mm sieve. The marked living bivalves, spent shells (dead bivalves with tissues gone), and gapers (recently dead shells still containing soft parts) found in the tray were counted and measured. Mortality of gapers and spent shells was attributed to senescence, disease, or limiting physical or chemical factors (non-predatory mortality), following the approach of Ford et al. (2006). Individuals not found in the trays (lost clams) were considered eaten by predators (predator-driven mortality) during a given time interval, following the approach of Tenore et al. (1968). Next, the trays were refilled with sediment and measured bivalves. The missing and dead bivalves were replaced with individuals collected in the environment with the same approximate dimensions, and the trays were submerged to the bottom again.

Rate of mortality (R) was reported as the combined percentage of absent/dead animals in the experimental trays per week during the established time intervals, calculated according to the following formula:

where R is the rate of mortality in % per week, S is the number of live individuals at the beginning of each period, P is the number of lost individuals induced by predation or by non-predatory mortality, and N is the length of monitoring period in weeks.

To estimate the size-specific mortality rates, clams used for the experiment were divided into two length classes: small (< 25 mm) and large (≥ 25 mm).

Temperature, oxygen concentration, and salinity were measured on each sampling occasion by means of a WTW probe, model Multi 3110. Continuous temperature measurements were performed using a MiniDOT recorder by PME.

The sediment collected for chemical analyses was dried and manually ground in a mortar, and then sieved on a set of geological sieves, with meshes of 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25, 0.125, and 0.063 mm. The contribution of each fraction was determined based on weight. Data were processed by means of GRADISTAT software (Blott & Pye, 2001). The content of organic matter in sediment was determined by loss on ignition at a temperature of 500°C (Heiri et al., 2001).

Identification of fish and waterfowl predators

The gut contents of potential fish and waterfowl predators were examined to determine the role of R. cuneata in their diet. Fish were collected in July, September, and October 2014, and in May and October 2015 in the direct vicinity of the experimental area. In summer, three nets of the Nordic type for near-shore harvests were applied. Each of the nets was composed of nine panels with mesh from 15 to 60 mm, a height of 1.8 m, and a total length of 45 m. In spring and autumn, the Nordic type net for autumn harvests was set, composed of 6 panels with mesh from 25 to 60 mm, a height of 3 m, and a total length of 180 m. Eels caught in fyke nets were obtained from local fishermen. Nets were set at dusk and collected early in the morning. In summer, the mean exposure time was approximately 9 h, in autumn—12 h. Fish were counted and measured to the nearest 1 mm total length and weighed to the nearest 1 g. The digestive tracks of roach Rutilus rutilus (L.), gibel carp Carassius gibelio (Bloch), white bream Blicca bjoerkna (L.), European flounder Platichthys flesus (L.), European perch Perca fluviatilis L., pikeperch Sander lucioperca (L.), and European eel Anguilla anguilla (L.) were dissected and preserved in 8% buffered formaldehyde solution. The digestive contents were examined for the presence of clams using a stereomicroscope (Hyslop, 1980). Dead ducks [tufted duck Aythya fuligula (L.), greater scaup A. marila (L.), and velvet scoter Melanita fusca (L.)] were obtained as by-catch from local fishermen during commercial fishing in the west part of the Vistula Lagoon, in September and October 2016. The material contained only seven individuals because of the difficulty of obtaining dead ducks. In the laboratory, the ducks were sexed, and their stomach contents were removed, preserved with 80% ethyl alcohol, and analysed under a stereomicroscope.

Analyses of parasites and epibionts

Clams for analyses were collected in the area of the field experiment. A total of 128 clams were collected in August 2014 with a mean length of 27.7 mm (range: 15.3–46.5 mm, SD: ± 9 mm), and 181 clams in September 2014 (range: 16.1–33.7 mm, SD: ± 7.5 mm). The clams were transported to a laboratory where they were kept in water from the lagoon at room temperature in plastic containers (35 × 24 × 13 cm) with aeration. Fifty-to-seventy clams were placed in each container. After 24 h, the water was transferred to Petri dishes and analysed for cercariae. Then, the containers were supplemented with new water, and after 24 h, the process was repeated. Next, the clams were subject to standard parasitological sections. The external and internal surfaces of the shell and internal organs were examined under a stereomicroscope. Moreover, parenchymal organs (digestive gland, gonads) were examined under a transmission light microscope after being pressed between glass slides. We used basic parasitological parameters to determine the level of infection of the clams: prevalence (percentage of infected hosts), mean intensity (mean number of parasites or epibionts in one infected host), and range of intensity (the lowest and highest number of parasites or epibionts in the analysed infected infrapopulation). In the case of ciliates, which develop tree-like colonies, due to small sizes and difficulty of precise count, intensity was determined descriptively: single (up to ten), moderately abundant (from 11 to 50), and abundant (more than 50).

Statistical analyses

Due to non-normal distribution of variables (Shapiro–Wilk test), we used non-parametric statistics. The Friedman non-parametric ANOVA test was applied in the analyses of the impact of time and size classes of clams on their mortality. Analyses of pairs of variables (small vs. big clams) were performed by means of a Wilcoxon test.

Results

Physical and chemical properties of water and bottom sediments

The environmental conditions during the experiment were typical of the Vistula Lagoon, with salinity and chlorophyll-a concentration fluctuating considerably (Fig. 2, Table 1).

Water transparency was low, resulting not only from relatively high chlorophyll-a concentrations and luxuriant development of phytoplankton, but also from frequent wind-driven resuspension of suspended solids. Water oxygenation at the bottom was high, probably due to low depth and strong mixing.

Continuous measurements of water temperature suggest a strong temporal pattern (Fig. 3) typical of the zone of moderate marine climate, with maximum temperatures in summer and low temperatures from November to April of the following year. Ice cover persisted for a relatively short period of slightly more than 1 week in December 2014.

Sediments from the experimental trays were fine-grained sand (diameter 0.163 mm) with negligible content of organic matter (1.55%). Such sediment allows clams to burrow to a depth of 6 cm (Kornijów, Drgas, Pawlikowski, unpubl.).

Temporal changes in mortality of R. cuneata

Time significantly affected both predator-induced losses [Friedman ANOVA (N = 5, df = 4) = 10.3, P = 0.035] and non-predatory mortality [Friedman ANOVA (N = 5, df = 4) = 11.6, P = 0.021] of the bivalves (Fig. 4). With the exception of the spring and early summer seasons, mortality from predation was higher than that caused by abiotic factors, but this relationship was not statistically significant [Friedman ANOVA (N = 5, df = 4) = 4.1, P = 0.394], probably due to the high variance of the data set.

Predatory mortality was not recorded in early summer (5 June–21 July 2014). It was observed only between late summer and spring of the following years (4 September 2014–26 May 2015), with a maximum between late autumn and early spring (17 October 2014–24 April 2015). Non-predatory mortality was negligible in summer and early autumn (21 July–16 October), and increased substantially between late autumn and late spring (17 October 2014–26 May 2015). Mass non-predatory mortality occurred particularly in spring, as evidenced by a high percentage (54%) of recently dead individuals with soft tissue still present in the shells (gapers) among all dead clams (gapers and spent shells) on 24 April 2015. The phenomenon was preceded by considerable spikes in salinity and an increase in water temperature to approximately 10°C (Figs. 2, 3). A month later, on 26 May 2015, the contribution of gapers was considerably lower and amounted to 16%. Such a course of mortality was confirmed by field observations (sampling from the environment).

Clam size versus mortality rates

Higher predatory mortality was observed in the group of smaller clams, whereas non-predatory mortality was higher among larger ones (Fig. 5). The dependence was statistically significant in the case of predatory mortality (Wilcoxon paired-samples test; P = 15, P = 11.0, P = 2.8, P = 0.005) but not for non-predatory mortality (Wilcoxon paired-samples test; N = 12, T = 16.0, Z = 1.8, P = 0.071).

Rangia cuneata as prey of fish and waterfowl

Rangia cuneata was observed in the guts of five fish species (Table 2). The contribution of bivalves in the food of fish was usually low, not exceeding approximately 10% of its volume. It was difficult to estimate in quantitative terms, because shells found in the gut content were badly crushed. The eel was an exception. Entire shells with a length from 7 to 17 mm were found in their stomachs.

Rutilus rutilus had the highest contribution of digestive tracts containing clams, and also a substantial share of biomass among clam consumers (Table 2). Blicca bjoerkna, dominant among the molluscivores of the lagoon, was represented by a few individuals with R. cuneata in their guts.

All three examined duck species consumed clams. Their stomachs contained both crushed and entire shells with a length of up to 14 mm. The contribution of clams in the stomach contents varied from several to 100% (Table 3).

Parasites/epibionts

We found no internal parasites associated with the clams. Epibiotic ciliates Sessilida were recorded around the siphons, and zebra mussels Dreissena polymorpha (Pallas) on the shell surface. Ciliates were located on the mucosal excretion directly around the siphons of R. cuneata, and zebra mussels on the rear part of the shell near the siphons. Differences in the occurrence of epibionts were recorded both in particular months and length classes of R. cuneata (Table 4).

Discussion

No research has been conducted on temporal patterns of survivorship/mortality of R. cuneata throughout the year. The literature on the subject provides only data referring to single findings concerning winter mass mortality of clams probably caused by factors unrelated to predation (Tenore et al., 1968; Gallagher & Wells, 1969; Hopkins & Andrews, 1970; Gusev & Rudinskaya, 2013).

The results of the experiment carried out in the Vistula Lagoon suggest considerable natural clam non-predatory mortality not in winter, as we expected, but between late autumn and spring of the following year. Our first hypothesis regarding the effects of abiotic factors was, therefore, not confirmed. Due to almost complete lack of ice cover, the lagoon water must have been well oxygenated, also right above the sediments, because of low water temperature and, therefore, high solubility of oxygen and low rate of the processes of organic matter decomposition. Therefore, oxygen deficits can be excluded as the cause of increased mortality. Hypoxic conditions in the bottom habitats of the Vistula Lagoon and increased mortality of clams can be expected during persistent ice cover (Warzocha et al., 2016). Notice, however, that R. cuneata is extremely resistant to oxygen depletion (Hopkins, 1970; LaSalle & de la Cruz, 1985). Water salinity was also unlikely to cause mass mortality during the experiment. It varied between 2.5 and 5.5 PSU, i.e., in a range well tolerated by the clam (LaSalle & de la Cruz, 1985; Auil-Marshalleck et al., 2000).

Numerous studies attribute increased mortality of bivalves to low temperatures. This may act in concert with other factors in the case of extreme, catastrophic environmental events, e.g., storms (Dame, 1996; McMahon, 2002). Rangia cuneata is a thermophilous species (Lane, 1986a) originating from an area with a subtropical marine climate, where water temperature is rarely below 10°C. Whereas short-term decreases in water temperature are not necessarily lethal for the species (Hopkins & Andrews, 1970), it is doubtful for it to have developed adaptations for survival in waters at a temperature around 4°C for a period of several months, as was the case in the Vistula Lagoon. Moreover, low temperature could considerably limit primary production, and, therefore, negatively affect food conditions of the filter-feeding R. cuneata. In consequence, low temperatures persisting for several months could have both directly and indirectly weakened the condition of bivalves (Lane, 1986b; French & Schloesser, 1991; Werner & Rothhaupt, 2008; Müller & Baur, 2011). Our field observations performed during the experiment and in 2017 (Kornijów, Drgas, Pawlikowski, unpubl.) show that mass mortality does not occur during and immediately after the end of winter, but several weeks later, in spring, when water temperature begins to exceed approximately 10°C. Mass mortality reaching 51.1% in the period from April to June 2012 in the Russian part of the Vistula Lagoon was also recorded by Gusev & Rudinskaya (2013).

Periodic mass mortality of clams undoubtedly has considerable consequences for the functioning of the entire ecosystem. The presence of easily available biomass in the form of dead soft tissue of clams is equivalent to rapid enrichment of the food base of microorganisms, invertebrates, and fish. This, in turn, can have a strong effect on food-web interactions (Sousa et al., 2012). Part of the biomass can enter the detrital pathway, driving changes in microbial biomass and nutrient cycles (Cherry et al., 2005; Sousa et al., 2014). Decomposing tissues must also negatively affect the sanitary state of waters, although research on the subject is scarce. Empty shells accumulated on the surface of sediments are of habitat-forming importance for many representatives of benthos, particularly for those which require a hard bottom (Gutierrez et al., 2003).

In conclusion, the high periodical mortality of R. cuneata in the Vistula Lagoon might be related to low temperatures during long winters, leading to the exhaustion of the organisms. Unfavourable thermal conditions could further contribute to increased mortality caused by epibionts and parasites (e.g., Gargouri Ben Abdallah et al., 2012).

Parasites and epibionts associated with R. cuneata are little known (Fairbanks, 1963; Wardle, 1983; Reece et al., 2008). Clams from the Vistula Lagoon proved to be free from parasites. This can result from several factors, including lack of suitable/specific intermediate and definitive hosts for potentially imported parasites, resulting in their disappearance in new conditions. During their importation, a process potentially extended in time (e.g., transport in ship ballast water), “cleaning” of hosts from parasites could also occur. It should be emphasised that our results are preliminary, because they were based on only two sets of samples collected in summer and early autumn. Therefore, the presence of parasites in other seasons cannot be excluded.

Among epibionts, we recorded ciliates Sessilida on siphons of R. cuneata and zebra mussels D. polymorpha on the surface of clam shells. The nature of the relationships of epibiotic ciliates with their bivalve hosts is typically not well defined, but appears to range from commensalism to parasitism. Epibiotic ciliates are observed in different species of aquatic animals, among others in crustaceans, bivalves, and even fish, where in the case of high intensity, and/or under conditions of intensified environmental stress (Molloy et al., 1997), they can limit breathing and feeding, and even damage the tegument/skin and gill epithelium, additionally, providing conditions for secondary bacterial infections (Hazen et al., 1978; Colorni, 2008). Recording D. polymorpha in the Vistula Lagoon only on large individuals of R. cuneata deserves particular attention. Apparently, only large clams have a suitable surface area to be inhabited by D. polymorpha (Bodis et al., 2014). In addition to the surface area, the strength/resistance of the clam sufficient to bear the additional weight can also be an important factor. Perhaps, smaller clams are also inhabited by zebra mussels but soon die due to the additional weight. Moreover, owing to its size (mass), D. polymorpha can hinder horizontal movement of R. cuneata, and its burrowing in sediments, which probably constitutes a method of avoiding predation (Tenore et al., 1968). Zebra mussels attached to shells of R. cuneata may also increase the risk of predation for the latter due to increased visibility to predators (Hoppe et al., 1986). The phenomenon may accelerate the process of incorporation of R. cuneata in the diet of predators. It should be considered, however, that in our study, zebra mussels most frequently inhabited large clams that were largely unavailable for predators, so this mechanism probably did not occur.

The fact that small individuals of R. cuneata were the most susceptible to predation can be related to the fact that their shell, probably serving as the main line of anti-predator defence (Blundon & Kennedy, 1982; Leonard et al., 1999; Czarnołęski et al., 2006; Wilkie & Bishop, 2012), is thin and easy to crush. In addition, Sylvester et al. (2007), studying the effect of fish on invasive bivalves Limnoperna fortunei (Dunker) in the Parana River, determined stronger predator pressure on smaller individuals. Magoulick & Lewis (2002) observed an opposite pattern in a reservoir in Arkansas, where fish preferred larger D. polymorpha. In that case, however, it could have resulted from the fact that even large zebra mussels have relatively thin shells.

The literature provides information on cases of both very strong pressure of native predators on invasive molluscs (Robinson & Wellborn, 1988; Reusch, 1998; Byers, 2002b; Magoulick & Lewis, 2002; Sylvester et al., 2007; Watzin et al., 2008; Nakano et al., 2010; Carlsson et al., 2011; Millane et al., 2012) and weak pressure (Ilarri et al., 2014; Naddafi & Rudstam, 2014). According to the literature, post-settlement individuals of R. cuneata in its native area are eaten by a variety of predators: crabs, fish, alligators, birds, and mammals (Darnell, 1958; Perry et al., 2007; Davis, 2009).

It is very unlikely that the mortality observed in the experiment could be attributed to invertebrate predators. Among them, only the large Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis Milne-Edwards could be taken into consideration. However, its population, consisting of immigrants from the west Baltic (mitten crabs do not reproduce in the Vistula Lagoon due to insufficient salinity), is small (Wójcik-Fudalewska & Normant-Saremba, 2016). Moreover, their distribution is limited to the overgrown shallows, habitats not preferred by clams, and the analysis of the diets of crabs living in the natural environment indicates the dominant role of food of plant origin (Czerniejewski et al., 2010 and the literature therein).

As demonstrated by the experiment, the largest losses in clams due to predation did not occur in summer, as assumed by the first hypothesis, but in autumn and winter, perhaps as a result of the structure of predators. Our study shows that a number of not only fish but also birds in the lagoon feed on the clam. For all fish species, it is only a supplement, and not a dominant food component. The most numerous fish are potentially of highest importance in reducing the abundance of clams in the lagoon: roach, gibel carp, European eel, and European flounder. Among these species, only roach and European flounder are commonly known as important consumers of molluscs, including bivalves (Specziar et al., 1997; Lappalainen et al., 2005; Vinagre et al., 2008). The aforementioned species have probably become the greatest beneficiaries among fish of the presence of the clam in the environment. The enrichment of their food base can be expected to translate into the improvement of their individual condition and growth rate, provided that the fish become accustomed to a particular type of food. This usually requires time, because fish often avoid or reject novel food types (Warburton, 2003; Carlsson & Strayer, 2009; Carlsson et al., 2011; Raubenheimer et al., 2012).

Rangia cuneata seems to play a more important role as food for the ducks of the Vistula Lagoon. They predominantly ate small clams with a length of up to 14 mm. According to the literature, however, they can feed on considerably larger bivalves reaching even 30 mm in length (Richman & Lovvorn, 2003). The information on the contribution of R. cuneata in the food of the waterfowl in the Vistula Lagoon has a signal character, because the sample was relatively small. In Europe, the potential consumers of clams also include coot Fulica atra L. and diving ducks, e.g., common goldeneye Bucephala clangula (L.) (Hoppe et al., 1986; Ponyi, 1994; Winfield & Winfield, 1994; Molloy et al., 1997). Their abundance in the Vistula Lagoon, especially during mild winters when no ice cover appears, reaches thousands of individuals (Goc & Mokwa, 2011). During this period, the demand of birds for food, in contrast to ‘cold-blooded’ (ectothermic) fish, strongly increases, and might translate into more intensive predation. Rangia cuneata is probably an easy prey. It does not attach to surfaces, and, although some individuals burrow themselves entirely in both soft muddy and hard sandy bottom sediments (approximately 45 and 20%, respectively), others protrude above the sediment surface (Kornijów, Drgas, Pawlikowski, unpubl.). Due to the shallowness of the lagoon (not exceeding 3 m over most of its area), practically its entire surface constitutes feeding grounds for diving ducks, able to dive and prey in water up to several meters deep (Molloy et al., 1997). Local fishermen also observed other birds (gulls and crows) preying on R. cuneata in the Vistula Lagoon. The birds selected clams from exposed sediments (a result of a seiche), and then dropped them from heights onto hard surface until the shells cracked and the flesh could be removed. The phenomenon was also reported from other areas (Meire, 1993; Wiese et al., 2016).

Our results show that R. cuneata has become a substantial part of the local food chain, and predation seems to be one of the control mechanisms. It seems, however, that predators alone do not significantly hinder the growth of the invader population. Similar conclusions were drawn by Molloy et al. (1997) while analysing the role of predators as potential factors eliminating and controlling the invasive zebra mussel.

In conclusion, in the Vistula Lagoon, abiotic factors had the greatest effect on the mortality not during winter, as we had assumed, but several weeks later, in spring. Predation pressure has turned out to be the highest not in summer, as expected, but in the autumn–winter period. Therefore, our first hypothesis was not confirmed. The second hypothesis, assuming higher mortality among small clams rather than large ones, cannot be rejected, but only in reference to mortality caused by predators. Mortality induced by abiotic factors was higher among big clams.

References

Auil-Marshalleck, S., C. Robertsoon, A. Sunley & L. Robinson, 2000. Preliminary review of life history and abundance of the Atlantic rangia (Rangia cuneata) with implications for management in Galveson Bay, Texas. Management Data Series 171: 1–31.

Blott, S. J. & K. Pye, 2001. GRADISTAT: a grain size distribution and statistics package for the analysis of unconsolidated sediments. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms 26(11): 1237–1248.

Blundon, J. A. & V. S. Kennedy, 1982. Mechanical and behavioral aspects of blue-crab, Callinectes sapidus (Rathbun), predation on Chesapeake Bay bivalves. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 65(1): 47–65.

Bodis, E., B. Toth & R. Sousa, 2014. Impact of Dreissena fouling on the physiological condition of native and invasive bivalves: interspecific and temporal variations. Biological Invasions 16(7): 1373–1386.

Byers, J. E., 2002a. Physical habitat attribute mediates biotic resistance to non-indigenous species invasion. Oecologia 130(1): 146–156.

Byers, J. E., 2002b. Impact of non-indigenous species on natives enhanced by anthropogenic alteration of selection regimes. Oikos 97(3): 449–458.

Carlsson, N. O. L., H. Bustamante, D. L. Strayer & M. L. Pace, 2011. Biotic resistance on the increase: native predators structure invasive zebra mussel populations. Freshwater Biology 6(8): 1630–1637.

Carlsson, N. O. L. & D. L. Strayer, 2009. Intraspecific variation in the consumption of exotic prey—a mechanism that increases biotic resistance against invasive species? Freshwater Biology 54(11): 2315–2319.

Charles, H. & J. S. Dukes, 2007. Impacts of invasive species on ecosystem services. Ecological Studies 193: 217–237.

Cherry, D. S., J. L. Scheller, N. L. Cooper & J. R. Bidwell, 2005. Potential effects of Asian clam (Corbicula fluminea) die-offs on native freshwater mussels (Unionidae) I: water-column ammonia levels and ammonia toxicity. Journal of North American Benthological Society 24(2): 369–380.

Colorni, A., 2008. Diseases caused by Ciliophora. In Eiras, J., H. Segner, T. Wahli & B. G. Kapoor (eds.), Fish diseases, Vol. 1., Science Publishers New Hampshire, USA: 569–612.

Czarnołęski, M., J. Kozłowski, P. Kubajak, K. Lewandowski, T. Müller, A. Stańczykowska & K. Surówka, 2006. Cross-habitat differences in crush resistance and growth pattern of zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha): effects of calcium availability and predator pressure. Archiv für Hydrobiologie 165(2): 191–208.

Czerniejewski, P., A. Rybczyk & W. Wawrzyniak, 2010. Diet of the Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis H. Milne Edwards, 1853, and potential effects of the crab on the aquatic community in the River Odra/Oder Estuary (N.-W. Poland). Crustaceana 83(2): 195–205.

Dame, R. F., 1996. Ecology of Marine Bivalves: An Ecosystem Approach. CRC Press, Boca Raton.

Darnell, R. M., 1958. Food habits of fishes and larger invertebrates of Lake Pontchartrain, Louisiana, an estuarine community. Publications of the Institute of Marine Science University of Texas 5: 253–416.

Davis, C. D., 2009. A generalized food web for Lake Pontchartrain in Southeastern Louisiana. https://studylib.net/doc/8220586/a-generalized-food-web-for-lake-pontchartrain-in-southeas.

Fairbanks, L. D., 1963. Biodemographic studies of the clam Rangia cuneata Gray. Tulane Studies in Zoology 10(1): 3–47.

Ford, S. E., M. J. Cummings & E. N. Powell, 2006. Estimating mortality in natural assemblages of oysters. Estuaries and Coasts 29(3): 361–374.

French, J. R. P. & D. W. Schloesser, 1991. Growth and overwinter survival of the Asiatic clam, Corbicula fluminea, in the St-Clair River, Michigan. Hydrobiologia 219(1): 165–170.

Gallagher, J. L. & H. W. Wells, 1969. Northern range extension and winter mortality of Rangia cuneata. Nautilus 1(83): 22–25.

Goc, M. & T. Mokwa, 2011. Assessment of distribution and abundance of water birds in the Polish part of the Vistula Lagoon. Final Report (Contract No. TI.2-JB/63/73/10).

Gargouri Ben Abdallah, L., T. Chargui, S. Abidli & N. Trigui El Menif, 2012. Associated and digenean fauna of the mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis cultured on shellfish tables in the lagoon of Bizerta (Tunisia). Transitional Waters Bulletin 6(1): 20–33.

Gusev A. A. & L. V. Rudinskaya, 2013. Shell form and growth of a new alien species of Rangia cuneata (G. B. Sowerby, 1831) in the Vistula lagoon (Baltic Sea). Programme & Book of Abstracts, IV. International symposium, Invasion of alien species in holarctic, September 22–28th, 2013, Borok, Russia: 66.

Gutierrez, J. L., C. G. Jones, D. L. Strayer & O. O. Iribarne, 2003. Mollusks as ecosystem engineers: the role of shell production in aquatic habitats. Oikos 101(1): 79–90.

Hazen, T. C., M. L. Raker, G. W. Esch & C. B. Fliermans, 1978. Ultrastructure of red-sore lesions on largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides)—association of Ciliate Epistylis sp. and bacterium Aeromonas hydrophila. Journal of Protozoology 25(3): 351–355.

Heiri, O., A. F. Lotter & G. Lemcke, 2001. Loss on ignition as a method for estimating organic and carbonate content in sediments: reproducibility and comparability of results. Journal of Paleolimnology 25(1): 101–110.

Hill, A. M. & D. M. Lodge, 1999. Replacement of resident crayfishes by an exotic crayfish: the roles of competition and predation. Ecological Applications 9(2): 678–690.

Hopkins, S. H., 1970. Studies on the brackish water clams of the genus Rangia in Texas. Proceedings of the National Shellfish Association 60: 5–6.

Hopkins, S. H. & J. D. Andrews, 1970. Rangia cuneata on East Cost. Thousand mile range extension, or resurgence. Science 167(3919): 868–869.

Hoppe, R. T., L. M. Smith & D. B. Wester, 1986. Foods of wintering diving ducks in South-Carolina. Journal of Field Ornithology 57(2): 126–134.

Hyslop, E. J., 1980. Stomach contents analysis—a review of methods and their application. Journal of Fish Biology 17(4): 411–429.

Ilarri, M. I., A. T. Souza, C. Antunes, L. Guilhermino & R. Sousa, 2014. Influence of the invasive Asian clam Corbicula fluminea (Bivalvia: Corbiculidae) on estuarine epibenthic assemblages. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 143: 12–19.

Katsanevakis, S., I. Wallentinus, A. Zenetos, E. Leppakoski, M. E. Cinar, B. Ozturk, M. Grabowski, D. Golani & A. C. Cardoso, 2014. Impacts of invasive alien marine species on ecosystem services and biodiversity: a pan-European review. Aquatic Invasions 9(4): 391–423.

Kornijów, R., A. Drgas & K. Pawlikowski, 2017. The experimental set for in situ research of benthic communities in marine and freshwater ecosystems. Knowledge and Management of Aquatic Ecosystems. https://doi.org/10.1051/kmae/2017003.

Lane, J. M., 1986a. Upper temperature tolerances of summer and winter acclimatized Rangia cuneata of different sizes from Perdido Bay, Florida. Northeast Gulf Science 8(2): 163–166.

Lane, J. M., 1986b. Allometric and biochemical studies on starved and unstarved clams, Rangia cuneata (Sowerby, 1831). Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 95(2): 131–143.

Lappalainen, A., M. Westerbom & O. Heikinheimo, 2005. Roach (Rutilus rutilus) as an important predator on blue mussel (Mytilus edulis) populations in a brackish water environment, the northern Baltic Sea. Marine Biology 147(2): 323–330.

LaSalle, M. W. & A. A. de la Cruz, 1985. Species profiles: life history and environmental requirements of coastal fishes and invertebrates (Gulf of Mexico)—common rangia. US Fish and Wildlife Services Biologic Report. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 82 (11.31), TR EL-82-4, 16.

Leonard, G. H., M. D. Bertness & P. O. Yund, 1999. Crab predation, waterborne cues, and inducible defenses in the blue mussel, Mytilus edulis. Ecology 80(1): 1–14.

Magoulick, D. D. & L. C. Lewis, 2002. Predation on exotic zebra mussels by native fishes: effects on predator and prey. Freshwater Biology 47(10): 1908–1918.

McMahon, R. F., 2002. Evolutionary and physiological adaptations of aquatic invasive animals: r selection versus resistance. Canadian Journal of Fishery and Aquatic Sciences 59(7): 1235–1244.

Meire, P. M., 1993. The impact of bird predation on marine and estuarine bivalve populations: a selective review of patterns and underlying causes. NATO ASI Series Series G Ecological Sciences 33: 197–243.

Millane, M., M. F. O’Grady, K. Delanty & M. Kelly-Quinn, 2012. An assessment of fish predation on the zebra mussel, Dreissena polymorpha (Pallas 1771) after recent colonization of two managed brown trout lake fisheries in Ireland. Biology and Environment 112B(1): 1–9.

Molloy, D. P., A. Y. Karatayev, L. E. Burlakova, D. P. Kurandina & F. Laruelle, 1997. Natural enemies of zebra mussels: predators, parasites, and ecological competitors. Reviews in Fisheries Science 5(1): 27–97.

Möller, T. & J. Kotta, 2017. Rangia cuneata (G. B. Sowerby I, 1831) continues its invasion in the Baltic Sea: the first record in Pärnu Bay, Estonia. BioInvasions Records 6(2): 167–172.

Müller, O. & B. Baur, 2011. Survival of the invasive clam Corbicula fluminea (Muller) in response to winter water temperature. Malacologia 53(2): 367–371.

Naddafi, R. & L. G. Rudstam, 2014. Predation on invasive zebra mussel, Dreissena polymorpha, by pumpkinseed sunfish, rusty crayfish, and round goby. Hydrobiologia 721(1): 107–115.

Nakano, D., T. Kobayashi & I. Sakaguchi, 2010. Predation and depth effects on abundance and size distribution of an invasive bivalve, the golden mussel Limnoperna fortunei, in a dam reservoir. Limnology 11(3): 259–266.

Nawrocka, L. & J. Kobos, 2011. The trophic state of the Vistula Lagoon: an assessment based on selected biotic and abiotic parameters according to the Water Framework Directive. Oceanologia 53(3): 881–894.

Perry, M. C., A. M. Wells-Berlin, D. M. Kidwell & P. C. Osenton, 2007. Temporal changes of populations and trophic relationships of wintering diving ducks in Chesapeake Bay. Waterbirds 30: 4–16.

Ponyi, J. E., 1994. Abundance and feeding of wintering and migrating aquatic birds in two sampling areas of Lake Balaton in 1983–1985. Hydrobiologia 279(1): 63–69.

Raubenheimer, D., S. Simpson, J. Sánchez-Vázquez, F. Huntingford, S. Kadri & M. Jobling, 2012. Nutrition and diet choice. In Huntingford, F., M. Jobling & S. Kadri (eds.), Aquaculture and Behavior, Vol. 358. John Wiley & Sons, London: 150–182.

Reece, K. S., C. F. Dungan & E. M. Burreson, 2008. Molecular epizootiology of Perkinsus marinus and P-chesapeaki infections among wild oysters and clams in Chesapeake Bay, USA. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 82(3): 237–248.

Reusch, T. B. H., 1998. Native predators contribute to invasion resistance to the non-indigenous bivalve Musculista senhousia in southern California, USA. Marine Ecology Progress Series 170: 159–168.

Richman, S. E. & J. R. Lovvorn, 2003. Effects of clam species dominance on nutrient and energy acquisition by spectacled eiders in the Bering Sea. Marine Ecology Progress Series 261: 283–297.

Robinson, J. V. & G. A. Wellborn, 1988. Ecological resistance to the invasion of a fresh-water clam, Corbicula fluminea: fish predation effects. Oecologia 77(4): 445–452.

Rudinskaya, L. V. & A. A. Gusev, 2012. Invasion of the North American wedge clam Rangia cuneata (G.B. Sowerby I, 1831) (Bivalvia: Mactridae) in the Vistula Lagoon of the Baltic Sea. Russian Journal of Biological Invasions 3(3): 220–229.

Sala, O. E., F. S. Chapin, J. J. Armesto, E. Berlow, J. Bloomfield, R. Dirzo, E. Huber-Sanwald, L. F. Huenneke, R. B. Jackson, A. Kinzig, R. Leemans, D. M. Lodge, H. A. Mooney, M. Oesterheld, N. L. Poff, M. T. Sykes, B. H. Walker, M. Walker & D. H. Wall, 2000. Biodiversity—global biodiversity scenarios for the year 2100. Science 287(5459): 1770–1774.

Sousa, R., A. Novais, R. Costa & D. L. Strayer, 2014. Invasive bivalves in fresh waters: impacts from individuals to ecosystems and possible control strategies. Hydrobiologia 735(1): 233–251.

Sousa, R., S. Varandas, R. Cortes, A. Teixeira, M. Lopes-Lima, J. Machado & L. Guilhermino, 2012. Mass die-offs of freshwater bivalves as resource pulses. Annales de Limnologie—International Journal of Limnology 48(1): 105–112.

Specziar, A., L. Tolg & P. Biro, 1997. Feeding strategy and growth of cyprinids in the littoral zone of Lake Balaton. Journal of Fish Biology 51(6): 1109–1124.

Strayer, D. L., 1999. Effects of alien species on freshwater mollusks in North America. Journal of North American Benthological Society 18(1): 74–98.

Sylvester, F., D. Boltovskoy & D. H. Cataldo, 2007. Fast response of freshwater consumers to a new trophic resource: Predation on the recently introduced Asian bivalve Limnoperna fortunei in the lower Parana river, South America. Australian Ecology 32(4): 403–415.

Tenore, K. R., D. B. Horton & T. W. Duke, 1968. Effects of bottom substrate on the brackish water bivalve Rangia cuneata. Chesapeake Science 9(4): 238–266.

Trella K, J Horbowy (2014) Assessment of fish stocks, with particular emphasis on the population of bream and perch on the Vistula Lagoon in 2014. Report commissioned by the Polish Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. National Marine Fisheries Research Institute Gdynia, 46 [in Polish].

Verween, A., F. Kerckhof, M. Vincx & S. Degraer, 2006. First European record of the invasive brackish water clam Rangia cuneata (G. B. Sowerby I, 1831) Mollusca: Bivalvia. Aquat Invasions 1(4): 198–203.

Vinagre, C., H. Cabral & M. J. Costa, 2008. Prey selection by flounder, Platichthys flesus, in the Douro estuary, Portugal. Journal of Applied Ichthyology 24(3): 238–243.

Warburton, K., 2003. Learning of foraging skills by fish. Fish and Fisheries 4(3): 203–215.

Wardle, W. J., 1983. Two new non-ocellate trichocercous cercariae (Digenea: Fellodistomidae) from estuarine bivalved molluscs in Galveston Bay, Texas. Contribution in Marine Science 26: 15–22.

Warzocha, J. & A. Drgas, 2013. The alien gulf wedge clam (Rangia cuneata G. B. Sowerby I, 1831) (Mollusca: Bivalia: Mactridae) in the Polish part of the Vistula Lagoon (SE. Baltic). Folia Malacologica 21: 291–292.

Warzocha, J., L. Szymanek, B. Witalis & T. Wodzinowski, 2016. The first report on the establishment and spread of the alien clam Rangia cuneata (Mactridae) in the Polish part of the Vistula Lagoon (southern Baltic). Oceanologia 58(1): 54–58.

Watzin, M. C., K. Joppe-Mercure, J. Rowder, B. Lancaster & L. Bronson, 2008. Significant fish predation on zebra mussels Dreissena polymorpha in Lake Champlain, U.S.A. Journal of Fish Biology 73(7): 1585–1599.

Werner, S. & K. O. Rothhaupt, 2008. Mass mortality of the invasive bivalve Corbicula fluminea induced by a severe low-water event and associated low water temperatures. Hydrobiologia 613: 143–150.

Wiese, L., O. Niehus, B. Faass & V. Wiese, 2016. Ein weiteres Vorkommen von Rangia cuneata in Deutschland (Bivalvia: Mactridae). Schriften zur Malakozoologie aus dem Haus der Natur-Cismar 29: 53–60.

Wilkie, E. M. & M. J. Bishop, 2012. Differences in shell strength of native and non-native oysters do not extend to size classes that are susceptible to a generalist predator. Marine and Freshwater Research 63(12): 1201–1205.

Williamson, M. & A. Fitter, 1996. The varying success of invaders. Ecology 77(6): 1661–1666.

Winfield, I. J. & D. K. Winfield, 1994. Feeding ecology of the diving ducks pochard (Aythya ferina), tufted duck (A. fuligula), scaup (A. mania) and goldeneye (Bucephala clangula) overwintering on Lough Neagh, Northern Ireland. Freshwater Biology 32(3): 467–477.

Wójcik-Fudalewska, D. & M. Normant-Saremba, 2016. Long-term studies on sex and size structures of the non-native crab Eriocheir sinensis from Polish coastal waters. Marine Biology Research 12(4): 412–418.

Acknowledgements

The work was conducted as part of statutory activities of the Department of Fisheries Oceanography and Marine Ecology of the National Marine Fisheries Research Institute, project number: Dot17/Rangia. The authors are grateful to the Institute of Meteorology and Water Management National Research Institute, Maritime Branch of Gdynia for providing data concerning water salinity in the Vistula Lagoon in the period 2014–2015. We also thank the editor and two anonymous reviewers for their careful reading and constructive comments, and Dr. David Strayer for his help with the English language.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Handling editor: Jonne Kotta

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kornijów, R., Pawlikowski, K., Drgas, A. et al. Mortality of post-settlement clams Rangia cuneata (Mactridae, Bivalvia) at an early stage of invasion in the Vistula Lagoon (South Baltic) due to biotic and abiotic factors. Hydrobiologia 811, 207–219 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-017-3489-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-017-3489-4