Abstract

This resampling study in 338 semi-permanent plots analyses changes in river macrophyte diversity in 70 water courses (small streams to medium-sized rivers) from four regions of the northwest German lowlands during the last six decades. The total macrophyte species pool decreased between the 1950s and 2010/2011 by 28% (from 51 to 37 species), mean plot-level species richness by 19% (from 4.7 to 3.8 species per relevé) and the number of red-listed species by 40% (from 30 to 18 species). Species loss was associated with marked change in species traits: species with presumably higher mechanical stress tolerance (indicated by low specific leaf area and short leaf longevity) are more abundant today. Nearly, half of the species present in the 1950s had either disappeared or been replaced by other species in the recent relevés. The dramatic impoverishment is likely a consequence of continued nutrient input that drove oligo- and mesotraphent species to extinction, and of restructuring and maintenance works in the water courses that reduced stagnant and undisturbed river habitats, where stress-intolerant species can persist. Efficient measures to reduce the nutrient load and to re-naturalise stream and river beds are urgently needed to halt and reverse the loss of macrophyte diversity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With less than 100 species, the hydrophytic macrophyte flora (Charophyta, Bryophyta, Pteridophyta and Spermatophyta) of Central Europe’s running waters is relatively species-poor (Casper & Krausch, 1981), but rich in different growth forms reflecting the considerable diversity of habitat types being present in streams and rivers of variable sizes, current velocities, water chemistries and sediment types. With rapidly increasing amounts of fertilizers used in the agricultural landscape and manifold hydro-engineering measures completed, the biota of running waters have been exposed to an ever-increasing pressure in the last century with consequences for macrophyte diversity and community composition (Phillips et al., 1978; Robach et al., 1996; Smith et al., 1999; Egertson et al., 2004; Hilton et al., 2006; Kozlowski & Vallelian, 2009). Eutrophication of water bodies by oxidised and reduced nitrogen compounds, but also by phosphorus, is known to cause profound shifts in the plant community composition of running waters, where rooted macrophytes may eventually be replaced by green macroalgae or phytoplankton as a consequence of light deficiency (Sand-Jensen & Borum, 1991; Vadineanu et al., 1992; Marques et al., 2003).

Aquatic macrophytes have frequently been used in limnology and vegetation ecology as reliable indicators of habitat conditions in running waters, because various species respond sensitively to alteration in water chemistry and/or current velocity (Kohler & Schneider, 2003; Schaumburg et al., 2004; Daniel et al., 2006; Demars & Trémolières, 2009). As an outcome of macrophyte monitoring, plenty of information exists on the ecological conditions of streams and rivers in many European regions (Pott, 1980; Wiegleb, 1981; Riis et al., 2000; Kuhar et al., 2007; Grinberga, 2011). However, this information is predominantly of qualitative nature and does not provide reliable information on long-term changes in the diversity and composition of the vegetation or alteration in environmental conditions that affect community composition. Only a limited number of studies on long-term change in river macrophyte communities covering several decades exists (Whitton & Dalpra, 1967; Holmes & Whitton, 1977; Herr et al., 1989; Mesters, 1995; Whitton et al., 1998; Riis & Sand-Jensen, 2001; Schwieger, 2002; Schütz et al., 2008) and an over-regional picture of diversity loss has not yet emerged.

This study uses a semi-permanent plot approach to analyse long-term change in the macrophyte vegetation of 70 streams and rivers from four regions in northwest Germany from the mid of the twentieth century until present. We resampled 338 relevés taken between 1936 and 1969 in 2010/2011 and analysed changes in species diversity, abundances of growth forms and functional traits at the community level including specific leaf area (SLA) and the indicator value for nitrogen. For a restricted data set, the temporal development of community change could be analysed among the 1950s, the 1980s and present. The aim of our study was to examine long-term changes in stream and river macrophyte vegetation from an over-regional perspective and, in case of changes, to elucidate the possible drivers of change. More specifically, we asked (1) if the decrease in macrophyte species richness between the 1950s and 2010/2011 was a general phenomenon in all studied river systems, (2) if nutrient-demanding and stress-tolerant species increased proportionally and (3) if community change has been more profound between the 1950s and the 1980s than between the 1980s and 2010/2011.

Materials and methods

Study area

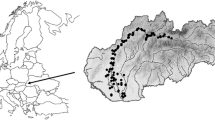

Four regions located in the Pleistocene north-west German lowlands with a variety of small streams to medium-sized rivers were selected for study. Region 1 comprising the Ems-Hunte moraine (mainly Dümmer lowlands) with acid base-poor moraine soils and bogs; region 2, the Lüneburg Heath (including the Aller lowlands) with base-poor sandy soils, both formed by the penultimate (Saale) Ice Age; region 3, (a) the northern Harz foothills with fertile Pleistocene loess deposits and (b) running waters at the base of the Weser-Leine uplands; and region 4, the eastern Holstein moraine with more base-rich young moraine soils of the last (Weichsel) Ice Age (Fig. 1). Region 3 combines the subregions (a) and (b), because all those sites are situated at the southern edge of the north German Pleistocene lowlands where runoff and groundwater are influenced by the silicate- or carbonate-rich bedrock of the uplands. In total, 70 rivers and streams were sampled (Table 1 in the Appendix—Supplementary Material) covering a broad range of water courses with small to medium size (1–40 m width and 0.2–2 m depth), current velocities between 0 and 50 cm s−1 and sandy or loamy sediments partly overlain by organic deposits or gravel. The catchments of all rivers are part of the cultural landscape of NW Germany, consisting of a mosaic of arable fields, pastures, meadows, forests and settlements. While the river sediments of the regions 1 and 2 are base-poor and those of the regions 3 and 4 moderately base-rich, in the last decades all streams and rivers have received considerable nutrient loads from the adjacent intensively managed agricultural land (Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz und Reaktorsicherheit, 2010). Due to the oceanic influence, the northwest German lowlands have a humid climate, characterised by warm summers and relatively mild winters with short frost periods. Mean annual temperatures range around 9°C, with lowest mean temperatures in January (0.4°C Braunschweig, Lower Saxony) and highest mean temperatures in July (17.2°C Hannover, Lower Saxony). The average annual precipitation lies between 656 mm y−1 (Hannover) and 754 mm y−1 (Kiel, Schleswig–Holstein) (all climate data from Deutscher Wetterdienst, 2012).

Data basis

We analysed data sets from three different periods (A: 1936–1969, B: 1983–1986, C: 2010/2011). Set A, referred to as the 1950s data, contains 338 relevés from the literature (Roll, 1939; Weber-Oldecop, 1969) and from the Reinhold-Tüxen-Archive in Hannover (Hoppe, 2005). The relevés deposited in the Tüxen archive were mostly taken by Rudolph Alpers in 1946. Set B contains 100 relevés from the 1980s of locations that were all sampled in the periods A and C (22 unpublished relevés from Herr & Wiegleb, 1984, 78 relevés from Herr, 1987, having already been processed e.g. in Herr et al. 1989). Set C contains present-day data of 338 locations congruent with set A. In the analysis, we first compared the data sets A (1950s) and C (2010/2011) (two-step comparison); in the second step, subsets of these two sets were compared with data set B (1980s), because only 100 sites were available that had been sampled in the 1950s, the 1980s and 2010/2011 (three-step comparison). The second analysis examined the time course of community change in more detail and the results are presented in the “Results” section (“Time course of community change: comparing the 1950s, the 1980s and 2010/2011”). Subset A ∈ B contains those data of set A that relate to the 100 locations of set B and subset C ∈ B includes the data of set C that refer to the 100 locations of set B. The plot sizes of the recent relevés (set C) were chosen in correspondence with the plot sizes of set A (varying between 1 and 100 m²). If no plot size was indicated in the historical relevés, a size of 40 m² was sampled, which is the average of all indicated plot sizes in several hundred relevés from streams and rivers available at the Tüxen archive. No uniform plot size could be achieved in the three-step-comparison (see below under “Methodological restrictions”).

Sampling design and field methods

Historical and recent vegetation analysis was conducted with the relevé method by determining all occurring plant species in a plot and estimating their cover either in percent or (in a few cases) in cover classes according to Braun-Blanquet (see Dierschke, 1994). In order to repeat the historical relevés (set A), the original sampling sites as indicated in the historical sources were revisited in the vegetation periods (June to September) of the years 2010 and 2011. In the reach of a sampling location, we chose a site where the macrophyte vegetation was well developed, because a similar selection procedure had generally been adopted by the authors 60 years ago. Particularly species-poor stands (e.g. under shading trees or next to artificial structures) were not selected. Relevé size was adapted to the size of the respective historical relevé. In addition, a standard plot size of 100 m² was sampled in 2010/2011 and used for the three-step-comparison. Vegetation was inspected using wade trousers and a telescopic rake was used in deep or very turbid water. The cover values of all macrophyte species that rooted in the river bed below the water level were recorded. In addition, several environmental parameters were recorded, notably the width and depth of the water body, flow velocity (determined in the stream line with the drift method as it had been used by Weber-Oldecop, 1969) and the sediment type within the plot.

Data analysis

Cover values that were available in scores of the scales according to Braun-Blanquet (1964; non-decimal) or Londo (1976; decimal) were transcribed into percentage cover values for every species, using the mean percent value of the respective class. All cover values, including those having been estimated in percent, were then transcribed into the mean percent value of the corresponding Braun-Blanquet class, to obtain consistent scaling among the data sets. Diversity changes were quantified using a modification of Shannon’s diversity index, i.e. true diversity D according to Jost (2006), with \( D = {\text{e}}^{{H^{\prime}}} \), where H′ is Shannon’s diversity index and D the number of species that would be needed to produce the given Shannon diversity value, if cover values were evenly distributed. For comparing the species composition of pairs of historical and recent relevés at a site, we calculated the dissimilarity index after Lennon (Lennon et al., 2001) with Lennon DI = min(b, c)/(min(b, c) + a), where a is the number of species being present in both relevés, b the number of species only occurring in relevé 1 and c the number of species only occurring in relevé 2. In contrast to other indices of species turnover, the Lennon DI does not generate high dissimilarities from high differences in species richness, but concentrates on compositional differences with values between 0 (a relevé includes all species of the other relevé) and 1 (no species in common). The current red list of endangered ferns and flowering plants of Germany (Korneck et al., 1996) was used to identify endangered macrophyte species (see Table 2 in the Appendix—Supplementary Material). Plant growth forms were determined after Segal (1968), Mäkirinta (1978) and Wiegleb (1991). Information on pollination types was taken from the BiolFlor data base (Klotz et al., 2002) and on SLA from the LEDA database (Kleyer et al., 2008). The strategy type classification (CRS-system) follows Landolt et al. (2010). Information on leaf longevity and on the species’ ecological indicator values for temperature, nitrogen and soil reaction were taken from Ellenberg et al. (2001). The Ellenberg indicator values (EIVs), which are based on vast expert knowledge about the species, have repeatedly been proven for reliably characterising the environmental conditions of Central European plant communities (Hill et al., 2000; Diekmann, 2003; Jansson et al., 2007). They were available for all species occurring in the analysis except for the two aggregates. To facilitate the analyses, similar plant functional groups were aggregated: the pleustophyte group includes lemnids, ricciellids, ceratophyllids and hydrocharids; the potamids contain parvo- and magnopotamids. The group of zoogamous species contains all species pollinated by insects and/or snails. With respect to leaf longevity, only two categories (evergreen and summergreen) were distinguished and the analyses were run with the percental proportion of evergreens.

All statistical tests and correlation analyses were done with the package SPSS 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). When two time steps (1950s vs. 2010/2011) were compared and values were normally distributed (according to a Shapiro–Wilk test), the t test for paired samples was used to test for significance. For data that were not normally distributed and could not be transformed, the non-parametric Wilcoxon test was used. When three time steps (1950s vs. 1980s vs. 2010/2011) were compared, a repeated measures ANOVA was used to test for differences. In cases, where an overall effect was found, the differences between the groups were further tested with the Bonferroni post hoc test. The species richness estimator indices ACE, ICE, Chao 1, Chao 2, Jackknife 1, Jackknife 2, Bootstrap and MMmeans were calculated from species presence/absence matrices with the software EstimeS 8.20. An indicator species analysis (ISA) after Dufrêne & Legendre (1997), where indicator values are generated from a combination of a species’ frequency and abundance in a particular group, was carried out with PCOrd 5.1. ISA analyses comparing historical and recent samples were performed for each of the four study regions separately and also for the pooled data set across all regions. The indicator values were tested for significance using Monte Carlo randomizations with 9999 permutations (Bakker, 2008). A detrended correspondence analysis (DCA) (Hill & Gauch, 1980) was done with Canoco 4.56, where information on environmental and biological traits was correlated with the DCA axes in a post hoc manner. Traits were calculated for each relevé as means (EIVs, SLA) or proportions (growth forms, strategy types, leaf longevity) to be fitted on the ordination space in the form of arrows pointing into the direction in which the value of the variable increases (Leps & Smilauer, 2003). For variables that were not normally distributed we used Spearman correlation, for normally distributed variables Pearson correlation. The respective types of correlation analysis are listed in Table 3 in the Appendix—Supplementary Material.

Methodological restrictions

To achieve sufficient comparability among the different data sets, only hydrophytic species (plants with morphological adaptations to life in water in the form of submerged or floating leaves) were included in the analyses. Amphiphytes and terrestrial plants, which may have been present in certain relevés when taken at high water, were excluded, because these species were not treated uniformly by the different authors. In the three-step-comparison (time course analysis), relevés of different sizes had to be compared. The 1950s relevés (subset A ∈ B) had the smallest size, the 1980s relevés (set B) were largest and the 2010/2011 relevés (subset C ∈ B) were intermediate in size. It thus can be assumed that the species richness in the 1950s may have been rather underestimated, especially when compared to the richness in the 1980s. Despite these methodological shortcomings, it is probable that the species pool of each region was adequately characterised in our analysis even with the relatively small relevés of the 1950s, as most water courses were sampled at several sites (see also Fig. 4).

The reliability of species identification in historical time was not always sufficient. In case of two genera with difficult species determination, aggregates were used throughout the analyses: the species Callitriche cophocarpa Sendtner, C. obtusangula Le Gall de Kerlinou, C. palustris Linnaeus, C. platycarpa Kützing, C. stagnalis Scopoli and C. vigens Martinsson were summarised to C. palustris agg. and the species Ranunculus aquatilis L. and R. peltatus von Schrank were summarised to R. aquatilis agg. In the text, aggregates and hybrids are referred to as species. The floristic knowledge of the historical author R. Alpers was assumed to be very good; only the fact that he mistook Potamogeton natans L. for P. nodosus Poiret (based on his own notes as cited in Herr et al., 1989) was taken into account by correcting for this mistake. Similarly, the species identifications of D.W. Weber-Oldecop were considered to be reliable throughout. Regarding the earliest historical author H. Roll, who worked in region 4 (eastern Holstein), it astonishes that the common macrophyte Sparganium emersum Rehmann did not appear in his species lists. As taxonomical literature was not sufficiently developed in his time, he might have confused this species with Glyceria fluitans (L.) Brown (Weber-Oldecop, 1982) or Sparganium erectum L.; however, we did not change any identification into Sparganium emersum in Roll’s data for not increasing possible errors.

Results

Change in floristic composition and diversity between the 1950s and 2010/2011

In all 676 historical and recent relevés covered by the analysis, 55 hydrophytic macrophyte species were recorded. The number of macrophyte species dropped by 27.5% from 51 species in the 1950s to 37 species in 2010/2011. Four species [Elodea nuttallii (Blanchon) St. John, Potamogeton praelongus von Wulfen, P. trichoides von Chamisso & von Schlechtendal and Wolffia arrhiza (L.) Wimmer] were recorded in the recent, but not in the historical survey. On the other hand, 18 species [Helosciadium inundatum (L.) Koch, Hippuris vulgaris L., Juncus bulbosus L., Leptodictyum riparium (Hedwig) Warnstorf, Luronium natans (L.) Rafinesque, Nymphaea alba L., Potamogeton acutifolius Roemer & Schultes, P. alpinus Balbis, P. angustifolius Presl, P. compressus L., P. filiformis Persoon, P. friesii Ruprecht, P. gramineus L., P. obtusifolius Mertens & Koch, P. polygonifolius Pourret de Figeac, Ranunculus circinatus Sibthorp, Sparganium natans L. and Utricularia australis Brown] were present in the historical, but not in the recent 338 relevés. In region 1 (Ems-Hunte), the loss in species richness was largest (Table 1). Lennon’s pairwise dissimilarity between historical and present-day relevés was 0.46 indicating that 46% of the species of an average relevé pair were different and 54% of the species were identical. Highest dissimilarity between historical and recent relevés (70%) was observed in the Holstein region and lowest (36%) in the Lüneburg Heath region. The number of red-listed species present in the study area dropped by 40% from 30 in the 1950s to 18 in 2010/2011.

The mean number of species per relevé decreased from 4.7 to 3.8 between the 1950s and 2010/2011 (Fig. 2; Table 4 in the Appendix—Supplementary Material). Simultaneously, the percentage of red-listed species per relevé dropped from 20.4% to 8.6%, indicating a disproportionately larger decrease in this group. Diversity (true diversity D) declined from 2.8 to 2.3 in the whole sample. The ISA revealed 28 species (51% of the total species pool) to be suitable indicators in at least one region for either recent or historical relevés; in other words, the 28 species showed either a significant decrease or an increase in at least one of the regions (Table 2). Twenty-three species showed a decrease or increase between the 1950s and 2010/2011 that was significant in the whole sample and thus independent from the region. Within the species, the direction of change was highly consistent, i.e. nearly all species either increased or decreased in the four regions. However, 77% of the species with a significant frequency change decreased or increased in only one or two of the four regions pointing to a large regional influence on community change. Only three species (Nuphar lutea (L.) J. E. Smith, Potamogeton perfoliatus L., Ranunculus aquatilis agg.) showed a decrease in three of the four regions, only one species (Elodea nuttallii) showed an increase in three regions. The only species, which decreased in all four regions, was the Canadian Waterweed, Elodea canadensis Michaux, which thus served as a highly reliable indicator for running waters of the 1950s. The four regions differed considerably with respect to the number of decreased species. In region 3 (Harz foothills), 15 species decreased, in region 2 (Lüneburg Heath) 13, in region 1 (Ems-Hunte) 10 and in region 4 (eastern Holstein) 3. The numbers of species with frequency increase ranged from 1 to 3 in the regions. The ratio of decreased to increased species was highest in region 2 (ratio of 6.5) followed by region 3 (5.0), region 1 (3.3) and region 4 (3.0), indicating that the losses in species frequency and abundance were high in the Lüneburg Heath and comparably low in the Ems-Hunte region and in eastern Holstein. In all regions together, 21 species decreased and only 2 species increased.

Species richness, number of red-listed species and diversity (true diversity D) per relevé in the 1950s and in 2010/2011 (mean ± SE). Differences are significant at ***P < 0.001. The assignment of red-listed status refers to the species’ current vulnerability status according to Korneck et al. (1996)

Change in vegetation structure and biological traits between the 1950s and 2010/2011

The pleustophytic growth form types as well as vallisnerids increased in relative abundance from the 1950s to 2010/2011. In contrast, peplids, potamids, batrachids and nymphaeids declined. Isoetids disappeared completely (Fig. 3; Table 5 in the Appendix—Supplementary Material). Competitor-strategists proportionally declined, while ruderal- and stress-strategists increased. The abiotic pollination types anemogamy and hydrogamy declined in the study area, while the relative frequency of self-pollinated macrophyte species and species pollinated by insects or snails increased. Species with evergreen leaves showed a decline, while the proportion of summergreen (short-lived) species increased. Species with a high SLA, i.e. with leaves and lamina rich in aerenchymatic tissue, proportionally declined from the 1950s to 2010/2011 (Table 3).

Proportions of the different growth forms in the total number of species in the relevés of the 1950s and 2010/2011 (mean ± SE of 338 relevés); Ple. pleustophytes (lemnids, ricciellids, ceratophyllids, hydrocharids), Val. vallisnerids, Bry. bryids, Myr. myriophyllids, Elo. elodeids, Pep. peplids, Iso. isoetids, Pot. parvo- and magnopotamids, Bat. batrachids, Nym. nymphaeids. Significant differences are indicated (*** P < 0.001, ** P < 0.01, * P < 0.05)

Change in environmental conditions between the 1950s and 2010/2011

The mean EIVs for nitrogen and for temperature, calculated by averaging over all species of a relevé, have increased during the six decades of study (Table 3). No change was observed for the EIV for soil reaction (pH). Some major changes (significant at P < 0.001) in river hydrography took place since the 1950s: Across all 70 water courses, we found an increase in the mean width of the water course (from 7.8 to 10.1 m), an increase in mean water depth (from 0.8 to 1.1 m), but an apparent decrease in mean current velocity in the stream line (from c. 0.30 to c. 0.12 m s−1). The relative abundance of the different sediment types (more than 50% sand followed by gravel/stones, mud and loam in the order of decreasing frequency) remained relatively stable over time (Table 4). However, while all rivers were still flowing in their natural beds in the 1950s, reaches of the stream Bruchgraben and the river Grawiede (both region 1) have been restructured by cementation since then.

Time course of community change: comparing the 1950s, the 1980s and 2010/2011

The detailed temporal analysis with 100 plots studied in the 1950s, the 1980s and at present showed over all regions a continuous decline in total vegetation cover in the relevés from 57% in the 1950s to 43% in the 1980s and to 28% in 2010/2011. The absolute number of species declined by 15% between the 1950s and the 1980s and by another 12% between the 1980s and 2010/2011. Comparison of the number of observed species with the estimated number of species according to species richness estimator indices confirms that our analysis captured the present species pool to a large extent in all three sampling periods (Fig. 4). Despite the more or less continuous decrease in the over-regional macrophyte species pool size, the four regions followed individual patterns of change. A decrease between the 1950s and the 1980s in the total number of species present (−19 to 36%) was recorded only in two of the regions (Ems-Hunte and Harz foothills) and none of the regions showed species pool declines of more than 6% between the 1980s and 2010/2011 (Fig. 5a). This pattern was different for the number of red-listed species with decreases of 17–59% in two regions (Ems-Hunte and Holstein) between the 1950s and the 1980s and further decreases of 20–25% in all regions except region 1 (Ems-Hunte) in the subsequent second time interval (Fig. 5b). The change in species composition between the 1950s and the 1980s (42% of species exchanged) was more profound than the species turnover between the 1980s and 2010/2011 (37% of species exchanged).

Estimated number of species for the 1950s, 1980s and 2010/2011, differentiated by regions. Mean values calculated from the species richness estimator indices ACE, ICE, Chao 1, Chao 2, Jackknife 1, Jackknife 2, Bootstrap and MMmeans for data set B (1980s) and subsets A ∈ B (1950s) and C ∈ B (2010/2011). Given are the means and the average standard deviation over all relevés in a region

Rhizophytes with floating leaves, represented by the growth form types nymphaeids and batrachids, declined between the 1950s and the 1980s, while potamids show a decline between the 1980s and 2010/2011. Pleustophytes increased between the 1980s and 2010/2011 (Fig. 6; Table 6 in the Appendix—Supplementary Material). The relative abundance of species with a competitor strategy proportionally declined between the 1950s and 2010/2011 (Fig. 7a; Table 6 in the Appendix—Supplementary Material). In contrast, stress-tolerating species increased in the 60 years, while species with a ruderal strategy increased between the 1950s and the 1980s. We found a shift from a high proportion of evergreen species to a high proportion of summergreen species for the period from the 1980s to 2010/2011 (Fig. 7b). The average SLA of the species declined from c. 37 to c. 29 m² kg−1 with a large drop since the 1980s (Fig. 7c). The mean EIV for nitrogen strongly increased between the 1950s and the 1980s, but showed a tendency to decrease thereafter (Fig. 7d). The EIV for soil reaction showed a similar pattern with a peak in the 1980s.

Proportions of pleustophytic (lemnid, ricciellid, ceratophyllid and hydrocharid) and rhizophytic (nymphaeid, potamid and batrachid) growth form types in the total number of species present in the 1950s, 1980s and 2010/2011 (mean ± SE of 100 relevés). Different letters Significant differences between the sampling dates

The DCA analysis, based on 284 relevés of 100 locations that were sampled three times (in the 1950s, the 1980s and 2010/2011), revealed two main axes (eigenvalues 0.607 and 0.455) with the first axis sharing a close positive correlation with current velocity and a negative correlation with the EIVs for soil reaction (pH) and temperature (Fig. 8; Table 3 in the Appendix—Supplementary Material). Furthermore, the relative abundance of competitors and of batrachid species correlated positively with axis 1, while this axis showed negative correlations with the relative abundance of stress tolerators and pleustophytic species. The second axis correlated positively with time (i.e. the year of sampling) and the relative abundance of pleustophytes, and negatively with SLA, the number of red-listed species per relevé and the relative abundance of potamids.

DCA graph based on 100 relevés from the 1950s resampled in the 1980s and 2010/2011 together with data (plot-level means) on the abundance of red-listed species, specific leaf area (SLA), proportion of evergreen species and plant life/growth forms, strategy type abundance, Ellenberg indicator values (EIVs) for nitrogen, temperature and soil reaction and current velocity. For the ordination, species abundances were log-transformed and rare species were down-weighted; 15 relevés that did not contain macrophytes in recent time and one outlier were excluded

Discussion

Our analysis of long-term vegetation change in 70 water courses of variable size, flow velocity and bedrock chemistry in an extended area of NW Germany showed large reductions in the regional macrophyte species pool (−27.5%) and in plot-level species richness (−19.4%) during the past 60 years or so. The loss in the number of currently red-listed species (−40%) in the regional species pool was even larger indicating that species with specific habitat requirements, which are usually more threatened by habitat change than generalist species, were indeed most vulnerable. Species loss was related to marked changes in macrophyte community composition with nearly half of the species present in the relevés in the 1950s either having disappeared until 2010/2011 or having been replaced by other species. The current macrophyte communities are not only species-poorer but also consist of species with higher mechanical stress tolerance as indicated by a reduced SLA and shorter leaf duration. A large increase in the relative importance of pleustophytic species at the expense of potamid and nymphaeid species reflects the profound alteration in community structure during the past 60 years.

A more detailed analysis showed that species loss and community change occurred more or less continuously during the past six decades and may continue if no measures to halt biodiversity erosion are taken. However, we found large differences in the temporal evolution of vegetation change among the four studied regions, which reflect local developments in hydro-engineering and, likely, also in agricultural intensification. The diversity decline in the macrophyte vegetation of north-west German lowland water courses over six decades has to be attributed to a variety of causes. Increased nutrient inputs with the intensification of agriculture since the 1950s have accelerated the eutrophication of most freshwater habitats (Ellenberg & Leuschner, 2010). The loss of species with preference for oligotrophic waters in our study area, such as Helosciadium innundatum, Juncus bulbosus, Luronium natans, Potamogeton filiformis, P. polygonifolius, Sparganium natans or Utricularia australis, is most likely a direct consequence of eutrophication. The increase in the mean EIV for nitrogen from c. 6.0 to 6.4 between the 1950s and the 1980s reflects increased nutrient availability in the water courses. Furthermore, the increase in the pleustophytic species Ceratophyllum demersum, Lemna spp. and Spirodela polyrhiza is also most likely a consequence of eutrophication. Apart from these species being competitive in exploiting nutrients, their free-floating growth forms allow them to remain on or close to the water surface, where they can escape light limitation in phytoplankton-rich, turbid water. Ceratophyllum demersum is able to relocate its biomass into the uppermost water layer (canopy forming) under turbid water conditions (Garniel, 2008). Our results are in line with findings from streams in the Netherlands, where Mesters (1995) reported a shift from submerged to floating-leaved species over several decades, which he explained with increased water turbidity, because floating-leaved and emergent species do not depend on light transmission in clear water.

Potamal rivers are generally more affected by the influx of nutrient-enriched surface water from adjacent lands than rhitral water courses, because river water accumulates nutrients, while flowing through a catchment area with predominant agricultural land use. In fact, the changes in species composition were least pronounced in the groundwater-fed water courses of the Lüneburg Heath, which mostly have a rhitral character. While most rhitral streams are located in mountainous terrain, a number of running waters in the Lüneburg Heath region (region 2) are relatively cool in summer, due to groundwater inflow and thus also have rhitral characteristics, despite being located in the lowlands. In contrast, a comparatively high species turnover was found in the regions Ems-Hunte and eastern Holstein, where potamal rivers prevail in the intensively used agricultural landscape. With the embankment of the Dümmer lake and its main tributary Hunte river in 1953, the Dümmer lowlands, where the majority of sites in the Ems-Hunte region is located, have been transformed from a landscape dominated by swamps and fens to an area, where arable land is predominant and high nutrient inputs are affecting the wetland vegetation (Blüml et al., 2008). This regional development explains the huge loss of diversity in the Ems-Hunte region, where some effluents of the Dümmer lake have already reached the hypertrophic state (Niedersächsisches Landesamt für Ökologie, 2001).

Since the 1980s, some improvement in the nutrient status of the running waters of NW Germany has occurred. The slight decrease in the mean EIV for nitrogen, as observed since the 1980s, might reflect a decreased mineral nitrogen load in the studied river systems. The most important pathway of nitrogen into the water courses is runoff from agricultural lands, which accounts for about two-thirds of total input. This diffuse fraction remained relatively stable, while inputs from point sources could be substantially reduced between 1983 and 2005 (German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety & German Federal Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection, 2008). The input of phosphorus to surface waters has significantly decreased in the study area between 1980 and 1996, mainly as a consequence of reduced phosphorus contents in detergents and better sewage treatment (Schulz, 1999). It appears that the vegetation is responding only slowly to these achievements.

In consideration of the previously discussed eutrophication effects, our finding of a decline in the floating-leaved growth forms nymphaeids and batrachids is somewhat perplexing. However, apart from eutrophication effects, the loss in structural diversity of river beds is another complex of factors responsible for the macrophyte diversity decline in rivers and streams in Central Europe (Wiegleb et al., 1991). Looking at the respective species in detail, it becomes obvious that the nymphaeids Luronium natans and Nymphaea alba and the batrachids Potamogeton gramineus and P. polygonifolius as well as a myriophyllid species that disappeared, Ranunculus circinatus, are bound to habitats where the water is constantly stagnant to slowly flowing (Casper & Krausch, 1980, 1981). Due to the anthropogenic reduction in structural diversity especially in lowland water courses, areas protected from the current, like inlets and shallow sections in the transition zone to floodplains, have become rare since the 1950s (Kaiser, 1993; Rasper, 2001). In 2000, 85% of all river beds in the northern German federal state of Lower Saxony were in the state of having a substantially modified, unnatural morphological structure (Niedersächsisches Landesamt für Ökologie, 2001). With the aim to speed-up runoff and increase landscape drainage, many river beds were deepened and broadened and the river course straightened, resulting in the loss of retention areas and in an overall decrease in mean current velocity in the potamal rivers. These melioration measures were supplemented by stabilization works on the river beds conducted in Lower Saxony particularly between the 1950s and the 1980s (Wasserverbandstag e.V., 2011). In regulated lowland rivers, straightened and steep banks are limiting macrophyte growth (Lorenz et al., 2012). In addition, most of the studied lowland water courses are continuously maintained and hence subject to regular disturbance (Federal Water Act of Germany, 2009).

It is thus not surprising that stress-tolerant species make up the largest proportion of the macrophyte flora since the 1950s, which is interpreted as a sign that most water courses had lost their systems of dead channels and shallow side arms with its characteristic flora already decades ago. The proportional increase in the ruderal strategy type, which comprises species with a high reproduction rate and the ability of rapidly colonising open sediments, is a sign for irregular disturbance by maintenance works in the water courses (Trémolières, 2004). The increase in species with a low SLA may also indicate increased disturbance levels in recent time. In general, species with lower SLA and higher tissue density have a higher mechanical strength which facilitates survival in waters with higher flow velocity. We assume that in deepened and partly canalised water courses with temporarily high flow rates and a lack of retention areas, macrophytes with robust structure are favoured. We propose that the mean SLA of a macrophyte community and its change over time may serve as a suitable indicator of the hydromechanical stress that is imposed on the plants as a consequence of river construction works.

Half of the 18 species that have disappeared in the study area between the 1950s and 2010/2011 belong to the genus Potamogeton. A severe loss of Potamogeton species was also observed in Danish lakes and streams over the last 100 years and was related to low remaining habitat diversity and frequent disturbance in our times (Sand-Jensen et al., 2000). Our study confirms these findings, as only the fast-growing, disturbance-tolerant pondweeds Potamogeton crispus, P. natans and P. pectinatus are still relatively common in NW Germany. Nevertheless, the frequencies of these species have also decreased since the 1950s to 60–30% of their former values. As most Potamogeton species are pollinated by water and wind, the decline in potamids resulted in a general decrease in hydro-gamous and anemogamous species as well. Of the four species which have not been observed in the relevés before 2010/2011, Elodea nuttallii is a neophyte that was found in Germany for the first time near Münster (Westfalen) in 1953 and is now widespread (Starfinger & Kowarik, 2003). Potamogeton praelongus has always been a rare species in the study area (Casper & Krausch, 1980), while P. trichoides is a species considered vulnerable in Germany, where it has increased in the last decades (Haeupler & Muer, 2000; Ludwig et al., 2007). The latter is not a typical species of running waters; it is considered to be relatively abundant in ponds, ditches and canals throughout its native range in Europe, Asia and Africa (Allen, 2011).

Mean winter temperature in Lower Saxony has risen by 1.9°C from 1950 to 2005 (Haberlandt et al., 2010). That summergreen species have experienced a relative increase, while evergreen species decreased, is probably mainly a consequence of increased disturbance intensity and not related to altered winter temperatures. Summergreens, overwintering with seeds or turions in the sediment, may be more tolerant to cold winters than evergreen macrophytes. Recent warming may have supported the arrival of Wolffia arrhiza, an indicator species for warm temperatures, in the study area in the last decades. Further warming may result in profound community change as is indicated by a modelling study for Finland, which predicts substantial changes in macrophyte community composition by 2050 with an increase in emergent macrophytes that may overgrow sensitive submerged macrophyte species (Alahuhta et al., 2011). Nevertheless, in the perspective of two to three decades, eutrophication and river-engineering are likely to represent more important threats to the river macrophyte vegetation of Central Europe than climate warming. Evidence in support of this conclusion is the observed increase in R-strategists and the decrease in mean SLA in our data, and the finding of Garniel (1999) that, after decades of intensive water course maintenance with machines, the vegetation in many running waters of Schleswig–Holstein (northern Germany) mainly consists of mowing-tolerant species like Sparganium emersum, Nuphar lutea and Potamogeton pectinatus, which place their roots several decimetres deep in the sediment.

Conclusions

Our resampling study documents the long-term change in the running water macrophyte vegetation of four regions that may be representative for large parts of the northern German diluvial lowlands. Both the decrease in the regional species pool and in the plot-level diversity were dramatic with the consequence that most water courses are colonised nowadays by only species-poor, relatively uniform communities that contain a high proportion of species adapted to disturbance. While currently red-listed macrophytes were still relatively widespread in the 1950s, they are in many cases highly endangered in our times. This is, for example, the case for Myriophyllum alterniflorum, Isolepis fluitans (both endangered), Zannichellia palustris (near-threatened) and some magnopotamid species that have vanished in more than 50% of the sites visited, where they still occurred in the 1950s. The likely causes of the impoverishment are continued nutrient input from intensively managed agricultural land that caused the disappearance of oligo- and mesotraphent species and the restructuring of most river beds together with the continuous maintenance of water courses; these measures resulted in the loss of more stagnant stream and river habitats where stress-intolerant species are able to persist. Thus, measures to reduce the nutrient load in rivers and to re-naturalise the flow regime in selected river sections are urgently needed in order to halt and reverse the catastrophic loss of phytodiversity in Central European lowland rivers. Both, biodiversity conservation and flood risk management, would profit from the creation of floodplain retention areas with a variety of stagnant freshwater habitats. The loss of most specialist species in the macrophyte flora largely devaluates this group in its role as an indicator of environmental quality in streams and rivers.

References

Alahuhta, J., J. Heino & M. Luoto, 2011. Climate change and the future distributions of aquatic macrophytes across boreal catchments. Journal of Biogeography 38: 383–393.

Allen, D., 2011. Potamogeton trichoides. In IUCN, 2012. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.1, http://www.iucnredlist.org. Accessed Oct 15, 2012.

Bakker, J. D., 2008. Increasing the utility of indicator species analysis. Journal of Applied Ecology 45: 1829–1835.

Blüml, V., F. Körner, U. Marxmeier, M. Richter & A. Schönheim, 2008. Entwicklung und aktuelle Situation der Verlandungsvegetation des Dümmers (Niedersachsen). Osnabrücker Naturwissenschaftliche Mitteilungen 33(34): 19–46.

Braun-Blanquet, J., 1964. Pflanzensoziologie, Grundzüge der Vegetationskunde. Springer, Wien.

Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz und Reaktorsicherheit, 2010. Umweltbericht 2010. Berlin.

Buttler, K. P. & M. Thieme, 2011. Florenliste von Deutschland – Gefäßpflanzen, Version 3. Frankfurt a.M. http://www.kp-buttler.de. Accessed April 2, 2012.

Casper, S. J. & H. D. Krausch, 1980. Pteridophyta und Anthophyta 1.Teil: Lycopodiaceae bis Orchidaceae. In Ettl, H., J. Gerloff & H. Heynig (eds), Süsswasserflora von Mitteleuropa 23. Fischer, Stuttgart.

Casper, S. J. & H. D. Krausch, 1981. Pteridophyta und Anthophyta 2.Teil: Saururaceae bis Asteraceae. In Ettl, H., J. Gerloff & H. Heynig (eds), Süsswasserflora von Mitteleuropa 24. Fischer, Stuttgart.

Daniel, H., I. Bernez & J. Haury, 2006. Relationships between macrophytic vegetation and physical features of river habitats: the need for a morphological approach. Hydrobiologia 570: 11–17.

Demars, B. O. L. & M. Trémolières, 2009. Aquatic macrophytes as bioindicators of carbon dioxide in groundwater fed rivers. Science of the Total Environment 407: 4752–4763.

Deutscher Wetterdienst, 2012. http://www.dwd.de/bvbw/appmanager/bvbw/dwdwwwDesktop?_nfpb=true&_pageLabel=_dwdwww_klima_umwelt_klimadaten_deutschland&T82002gsbDocumentPath=Navigation%2FOeffentlichkeit%2FKlima__Umwelt%2FKlimadaten%2Fkldaten__kostenfrei%2Fausgabe__monatswerte__node.html%3F__nnn%3Dtrue. Accessed March 28, 2012.

Diekmann, M., 2003. Species indicator values as an important tool in applied plant ecology – a review. Basic and Applied Ecology 4: 493–506.

Dierschke, H., 1994. Pflanzensoziologie. Ulmer, Stuttgart.

Dufrêne, M. & P. Legendre, 1997. Species assemblages and indicator species: the need for a flexible asymmetrical approach. Ecological Monographs 67: 345–366.

Egertson, C. J., J. A. Kopaska & J. A. Downing, 2004. A century of change in macrophyte abundance and composition in response to agricultural eutrophication. Hydrobiologia 524: 145–156.

Ellenberg, H. & C. Leuschner, 2010. Vegetation Mitteleuropas mit den Alpen, 6th ed. Ulmer, Stuttgart.

Ellenberg, H., H. E. Weber, R. Düll, V. Wirth, W. Werner & D. Paulissen, 2001. Zeigerwerte von Pflanzen in Mitteleuropa. Scripta Geobotanica 18: 1–258.

Federal Water Act of Germany, 2009. Gesetz zur Neuregelung des Wasserrechts. Bundesgesetzblatt Teil 1(51): 2585–2621.

Garniel, A., 1999. Schutzkonzept für gefährdete Wasserpflanzen der Fließgewässer und Gräben Schleswig-Holsteins, Teil B: Fließgewässer. Unpublished report on behalf of the Landesamt für Natur und Umwelt Schleswig-Holstein, Flintbek.

Garniel, A., 2008. Wasserpflanzen der Fließgewässer und Gräben – Informationen zum Verständnis ihrer Lebensstrategien als Grundlage für Erhaltungs-und Fördermaßnahmen in Schleswig-Holstein und Hamburg. Berichte des Botanischen Vereins zu Hamburg 24: 1–221.

German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety & German Federal Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection, 2008. Nitrates report 2008. Joint report, Bonn.

Grinberga, L., 2011. Macrophyte species composition in streams of Latvia under different flow and substrate conditions. Estonian Journal of Ecology 60: 194–208.

Haberlandt, U., A. Belli & J. Hölscher, 2010. Trends in be-obachteten Zeitreihen von Temperatur und Niederschlag in Niedersachsen. Hydrologie und Wasserbewirtschaftung 54: 28–36.

Haeupler, H. & T. Muer, 2000. Bildatlas der Farn-und Blütenpflanzen Deutschlands. Ulmer, Stuttgart.

Herr, W. & G. Wiegleb, 1984. Vegetationskundliche Untersuchungen zur biologisch-ökologischen Situation Schleswig-Holsteinischer Fliessgewässer, Band 2: Tabellenband. Unpublished report on behalf of the Landesamt für Naturschutz und Landschaftspflege Schleswig-Holstein, Kiel.

Herr, W., 1987. Dynamik und Konstanz von Flora und Vegetation ausgewählter Fließgewässer Niedersachsens 1946 bis 1986. Unpublished report on behalf of the Niedersächsisches Landesverwaltungsamt, Fachbehörde für Naturschutz, Hannover.

Herr, W., G. Wiegleb & D. Todeskino, 1989. Veränderungen von Flora und Vegetation ausgewählter Fließgewässer Niedersachsens nach vierzig Jahren (1946/1986). Naturschutz und Landschaftspflege in Niedersachsachsen 18: 121–144.

Hill, M. O. & H. G. Gauch, 1980. Detrended correspondence analysis: an improved ordination technique. Vegetatio 42: 47–58.

Hill, M. O., D. B. Roy, J. O. Mountford & R. G. H. Bunce, 2000. Extending Ellenberg’s indicator values to a new area: an algorithmic approach. Journal of Applied Ecology 37: 3–15.

Hilton, J., M. O’Hare, M. J. Bowes & J. I. Jones, 2006. How green is my river? A new paradigm of eutrophication in rivers. Science of the Total Environment 365: 66–83.

Holmes, N. T. H. & B. A. Whitton, 1977. The macrophytic vegetation of the river Tees in 1975: observed and predicted changes. Freshwater Biology 7: 43–60.

Hoppe, A., 2005. Das Reinhold-Tüxen-Archiv am Institut für Geobotanik der Universität Hannover. Tuexenia 25: 463–474.

Jansson, R., H. Laudon, E. Johansson & C. Augspurger, 2007. Importance of groundwater discharge for plant species number in riparian zones. Ecology 88: 131–139.

Jost, L., 2006. Entropy and diversity. Oikos 113: 363–375.

Kaiser, A., 1993. Zur Geschichte der Ems – Natur und Ausbau. Veröffentlichungen aus dem Kreisarchiv Gütersloh 1: 1–181.

Kleyer, M., R. M. Bekker, I. C. Knevel, J. P. Bakker, K. Thompson, M. Sonnenschein, P. Poschlod, J. M. van Groenendael, L. Klimes, J. Klimesová, S. Klotz, G. M. Rusch, M. Hermy, D. Adriaens, G. Boedeltje, B. Bossuyt, A. Dannemann, P. Endels, L. Götzenberger, J. G. Hodgson, A.-K. Jackel, I. Kühn, D. Kunzmann, W. A. Ozinga, C. Römermann, M. Stadler, J. Schlegelmilch, H. J. Steendam, O. Tackenberg, B. Wilmann, J. H. C. Cornelissen, O. Eriksson, E. Garnier & B. Peco, 2008. The LEDA traitbase: a database of life-history traits of the Northwest European flora. Journal of Ecology 96: 1266–1274.

Klotz, S., I. Kühn & W. Durka, 2002. BiolFlor – Eine Datenbank zu biologisch-ökologischen Merkmalen der Gefäßpflanzen in Deutschland. Schriftenreihe für Vegetationskunde 38: 1–334.

Kohler, A. & S. Schneider, 2003. Macrophytes as bioindicators. Archiv für Hydrobiologie, Supplement 147: 17–31.

Koperski, M., M. Sauer, W. Braun & S. R. Gradstein, 2000. Referenzliste der Moose Deutschlands. Schriftenreihe für Vegetationskunde 34:1–519.

Korneck, D., M. Schnittler & I. Vollmer, 1996. Rote Liste der Farn-und Blütenpflanzen (Pteridophyta und Spermatophyta) Deutschlands. Schriftenreihe für Vegetationskunde 28: 21–187.

Kozlowski, G. & S. Vallelian, 2009. Eutrophication and endangered aquatic plants: an experimental study on Baldellia ranunculoides (L.) Parl. (Alismataceae). Hydrobiologia 635: 181–187.

Kuhar, U., T. Gregorc, M. Rencelj, N. Sraj-Krzic & A. Gaberscik, 2007. Distribution of macrophytes and condition of the physical environment of streams flowing through agricultural landscape in north-eastern Slovenia. Limnologica 37: 146–154.

Landolt, E., B. Bäumler, A. Erhardt, O. Hegg, F. Klötzli, W. Lämmler, M. Nobis, K. Rudmann-Maurer, F. Schweingruber, J.-P. Theurillat, E. Urmi, M. Vust & T. Wohlgemuth, 2010. Flora Indicativa – Ökologische Zeigerwerte und biologische Kennzeichen zur Flora der Schweiz und der Alpen. Haupt, Bern.

Lennon, J. J., P. Koleff, J. J. D. Greenwood & K. J. Gaston, 2001. The geographical structure of British bird distributions: diversity, spatial turnover and scale. Journal of Animal Ecology 70: 966–979.

Londo, G., 1976. The decimal scale for relevés of permanent quadrats. Vegetatio 33: 61–64.

Leps, J. & P. Smilauer, 2003. Multivariate analysis of ecological data using CANOCO. University Press, Cambridge.

Lorenz, A. W., T. Korte, A. Sundermann, K. Januschke & P. Haase, 2012. Macrophytes respond to reach-scale river restorations. Journal of Applied Ecology 49: 202–212.

Ludwig, G., R. May & C. Otto, 2007. Verantwortlichkeit Deutschlands für die weltweite Erhaltung der Farn-und Blütenpflanzen – vorläufige Liste. BfN Skripten 220: 1–102.

Mäkirinta, U., 1978. Ein neues ökomorphologisches Lebensformen-System der aquatischen Makrophyten. Phytocoenologia 4: 446–470.

Marques, J. C., S. N. Nielsen, M. A. Pardal & S. E. Jørgensen, 2003. Impact of eutrophication and river management within a framework of ecosystem theories. Ecological Modelling 166: 147–168.

Mesters, C., 1995. Shifts in macrophyte species composition as a result of eutrophication and pollution in Dutch transboundary streams over the past decades. Journal of Aquatic Ecosystem Health 4: 295–305.

Niedersächsisches Landesamt für Ökologie, 2001. Gewässergütebericht 2000. Oberirdische Gewässer 13: 1–40.

Phillips, G. L., D. Eminson & B. Moss, 1978. A mechanism to account for macrophyte decline in progressively eutrophicated freshwaters. Aquatic Botany 4: 103–126.

Pott, R., 1980. Die Wasser-und Sumpfvegetation eutropher Gewässer in der Westfälischen Bucht – pflanzensoziologische und hydrochemische Untersuchungen. Veröffentlichungen der Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Biologisch-Ökologische Landeserforschung 27, Münster.

Rasper, M., 2001. Morphologische Fließgewässertypen in Niedersachsen – Leitbilder und Referenzgewässer. Niedersächsisches Landesamt für Ökologie, Hildesheim.

Riis, T. & K. Sand-Jensen, 2001. Historical changes in species composition and richness accompanying perturbation and eutrophication of Danish lowland streams over 100 years. Freshwater Biology 46: 269–280.

Riis, T., K. Sand-Jensen & O. Vestergaard, 2000. Plant communities in lowland Danish streams: species composition and environmental factors. Aquatic Botany 66: 255–272.

Robach, F., G. Thiébaut, M. Trémolières & S. Muller, 1996. A reference system for continental running waters: plant communities as bioindicators of increasing eutrophication in alkaline and acidic waters in north-east France. Hydrobiologia 340: 67–76.

Roll, H., 1939. Die Pflanzengesellschaften ostholsteinischer Fließgewässer – Limnologisch-soziologische Studien. Archiv für Hydrobiologie 34: 159–305.

Sand-Jensen, K. & J. Borum, 1991. Interactions among phytoplankton, periphyton and macrophytes in temperate freshwaters and estuaries. Aquatic Botany 41: 137–175.

Sand-Jensen, K., T. Riis, O. Vestergaard & S. O. Larsen, 2000. Macrophyte decline in Danish lakes and streams over the past 100 years. Journal of Ecology 88: 1030–1040.

Schaumburg, J., C. Schranz, J. Foerster, A. Gutowski, G. Hofmann, P. Meilinger, S. Schneider & U. Schmedtje, 2004. Ecological classification of macrophytes and phytobenthos for rivers in Germany according to the Water Framework Directive. Limnologica 34: 283–301.

Schulz, F., 1999. Trendauswertung der stofflichen Belastung schleswig-holsteinischer Fließgewässer. In Landesamt für Natur und Umwelt Schleswig-Holstein. Jahresbericht 1999, Flintbek: 59–65.

Schütz, W., U. Veit & A. Kohler, 2008. The aquatic vegetation of the Upper Danube river – past and present. Large Rivers 162: 167–191.

Schwieger, F., 2002. Wasserpflanzen in Fließgewässern des niedersächsischen Elbegebietes. NLWK-Schriftenreihe 6, Lüneburg.

Segal, S., 1968. Ein Einteilungsversuch der Wasserpflanzengesellschaften. In Tüxen, R. (ed.), Pflanzensoziologische Systematik. Junk, The Hague: 191–218.

Smith, V. H., G. D. Tilman & J. C. Nekola, 1999. Eutrophication: impacts of excess nutrient inputs on freshwater, marine, and terrestrial ecosystems. Environmental Pollution 100: 179–196.

Starfinger, U. & I. Kowarik, 2003. Internet-Handbuch zum Erkennen und Bekämpfen invasiver Pflanzenarten. http://www.floraweb.de/neoflora/handbuch/elodeanuttallii.html. Accessed June 1, 2012.

Trémolières, M., 2004. Plant response strategies to stress and disturbance: the case of aquatic plants. Journal of Biosciences 29: 461–470.

Vadineanu, A., S. Cristofor & G. Ignat, 1992. Phytoplankton and submerged macrophytes in the aquatic ecosystems of the Danube Delta during the last decade. Hydrobiologia 243(244): 141–146.

Wasserverbandstag e. V. (ed.), 2011. Gewässerunterhaltung in Niedersachsen, Teil A. Rechtlich-fachlicher Rahmen, Hannover.

Weber-Oldecop, D. W., 1969. Wasserpflanzengesellschaften im östlichen Niedersachsen. Dissertation, University of Hannover.

Weber-Oldecop, D. W., 1982. Die Vegetation der Kossau. Die Heimat 89: 122–125.

Whitton, B. A. & M. Dalpra, 1967. Floristic changes in the river Tees. Hydrobiologia 32: 545–550.

Whitton, B. A., P. N. G. Boulton, E. M. Clegg, J. J. Gemmell, G. G. Graham, R. Gustar & T. P. Moorhouse, 1998. Long-term changes in macrophytes of British rivers: 1. River Wear. The Science of the Total Environment 210(211): 411–426.

Wiegleb, G., 1981. Struktur, Verbreitung und Bewertung von Makrophytengesellschaften niedersächsischer Fließgewässer. Limnologica 13: 427–448.

Wiegleb, G., 1991. Die Lebens- und Wuchsformen der makrophytischen Wasserpflanzen und deren Beziehungen zu Ökologie, Verbreitung und Vergesellschaftung der Arten. Tuexenia 11: 135–147.

Wiegleb, G., H. Brux & W. Herr, 1991. Human impact on the ecological performance of Potamogeton species in northwestern Germany. Vegetatio 97: 161–172.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the Reinhold-Tüxen-Archive (Hannover) for granting access to historical vegetation relevés. We thank Uta Müller (Göttingen) for help in the field work. For help in taxonomical questions, we cordially thank Günther Dersch (Bovenden), who cytologically determined numerous samples of Callitriche, Sebastian Dittrich (Göttingen), who identified most of the bryophytes and Gerhard Wiegleb (Cottbus), who identified Potamogeton and Ranunculus specimen and gave comments on a former draft of the manuscript. Jürgen Homeier (Göttingen) and Karsten Wesche (Görlitz) gave valuable advice on statistical methods. Dieter Todeskino (Oldenburg) is acknowledged as he took part in the sampling in the 1980s. The study was undertaken within the BioChange project funded by the Ministry of Science and Culture of Lower Saxony.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Steffen, K., Becker, T., Herr, W. et al. Diversity loss in the macrophyte vegetation of northwest German streams and rivers between the 1950s and 2010. Hydrobiologia 713, 1–17 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-013-1472-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-013-1472-2