Abstract

This paper investigates social-environmental factors contributing to differential ethnobotanical expertise among children in Rarámuri (Tarahumara) communities in Chihuahua, Mexico, to explore processes of indigenous ecological education and epistemologies of research. One hundred and four children from two schools (one with a Ráramuri knowledge curriculum and one without) were interviewed about their knowledge of 40 useful plants. Overall, children showed less ethnobotanical expertise than expected and a great deal of variability by age, though most shared knowledge of a core set of culturally and ecologically salient plants. No significant difference was found between girls’ and boys’ knowledge. The overall use-knowledge scores were almost twice as high as naming scores (mean of 40% vs. 24.4%). This supports the conclusion that use-context is more culturally relevant, salient or easier for children to remember than names. The social–environmental factors significant in predicting levels of plant knowledge among children were whether a child attended a Rarámuri or Spanish-instruction school, and, to a lesser extent, age. However, these effects were not strong, and individual variability in expertise is best interpreted using ethnographic knowledge of each child’s family and personal history, leading to a model of ethnobotanical education that foregrounds experiential learning and personal and family interest in useful plants. Though overall plant knowledge may be lower among children today compared to previous generations, a community knowledge structure seems to be reproduced in which a few individuals in each age cohort show great proficiency, and children make the same kinds of mistakes and share specialized names for plants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Voucher specimens were deposited at the herbarium of the Instituto Politécnico Nacional in Durango, Mexico (CIIDIR), where identifications were made.

Two were the same species, in order to check for consistency in interview answers.

The adult responses were not uniform; in cases of disagreement I inquired with others and referenced published sources and my own ethnobotanical observations.

Assumptions for ANOVA test include, 1) a random sample; 2) independence of variates; 3) normal data. The data presented here conform to assumptions 2 and 3, and, though the sample was not collected randomly, it constitutes a large percentage of the population and can be considered representative (see earlier discussion).

References

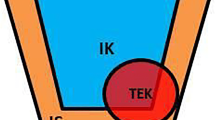

Agrawal, A. (1999). Ethnoscience, ‘TEK’ and Conservation. In Darrell, A. (ed.), Cultural and Spiritual Values of Biodiversity. Posey UNEP, Intermediate Technology Publications, London, pp. 177–180.

Benz, B. F., Sevallos, J., Santana, F., Rosales, J., and Graf, S. (2000). Losing knowledge about plant use in the Sierra de Manantlan Biosphere Reserve, Mexico. Economic Botany 54(2): 183–191.

Berlin, B. (1992). Ethnobiological classification: principles of categorization of plants and animals in traditional societies. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Berlin, B., Elois, A., Berlin, D. E., Breedlove, T., Duncan, V., Jara, R. M., Laughlin, and Velasco, T. (1990). La herbolaria médica Tzeltal-Tzotzil. Instituto Cultura Chiapaneco. Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas Mexico.

Borgatti, S. (1992). ANTHROPAC 4.0. Analytic Technologies, Columbia.

Boster, J. S. (1987). Introduction: Intracultural Variation. The American Behavioral Scientist 31: 150–162.

Boster, J. S. (1991). The Information Economy Model Applied to Biological Similarity Judgment. In Resnick, L., Levine, J., and Teasley, S. (eds.), Perspectives on Socially Shared Cognition, American Psychological Association, Washington, pp. 203–225.

Brambila, D. (1983). Diccionario rarámuri-castellano. Obra Nacional de la Buena Prensa, A.C., Mexico D.F.

Brunel, G. (1974). Variation in Quechua Ethnobiology. PhD dissertation, University of California, Berkeley.

Bye, R. A. (1985). Medicinal Plants of the Tarahumara Indians of Chihuahua, Mexico. In Tyson, R., and Elerick, D. (eds.), Two Mummies from Chihuahua, Mexico. San Diego Museum of Man, San Diego.

Bye, R. A. (1994). Prominence of the Sierra Madre Occidental in the Biological Diversity of Mexico. In Biodiversity and management of the Madrean archipelago and sky islands of SW U.S. and Northwestern Mexico, Vol. Report RM-GTR-264, pp. 19-26. USDA/FS/Rocky Mtn. Forest and Range Experimental Station, Ft. Collins.

Bye, R. A., Don B., and Trias A. M. (1975). Ethnobotany of the Western Tarahumar of Chihuahua, Mexico, vol. 112, Harvard University, Boston, p. 24.

Cardenal, F. (1993). Remedios y practicas curativas en la Sierra Tarahumara. Editorial Camino, Chihuahua.

Chipenuik, R. (1995). Childhood Foraging as a Means of Acquiring Competent Human Cognition About Biodiversity. Environment and Behavior 27(4): 490–512.

Dougherty, J. W. D. (1978). Salience and Relativity in Classification. American Ethnologist 5(1): 66–80.

Garro, L. C. (1986). Intracultural Variation in Folk Medical Knowledge: A Comparison Between Curers and Noncurers. American Anthropologist 88: 351–370.

Godoy, R., Reyes-García, V., Byron, E., Leonard, W. R., and Vadez, V. (2005). The Effect of Market Economies on the Well-Being of Indigenous Peoples and on Their Use of Renewable Resources. Annual Review of Anthropology 34: 121–138.

Heckler, S. (2006). On Knowing and Not Knowing: The Many Valuations of Piaroa Local Knowledge. In Sillitoe, P. (ed.), Local Science vs. Global Science: Approaches to Indigenous Knowledge in International Development. Berghahn Books, Oxford.

Hunn, E. S. (2008). A Zapotec natural history: trees, herbs, and flowers, birds, beasts, and bugs in the life of San Juan Gbëë. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Lerner, R. M., Castellino, D. R., Terry, P. A., Villarruel, F. A., and McKinney, M. H. (1995). Developmental Contextual Perspective on Parenting. In Bornstein, M. H. (ed.), Handbook of Parenting, vol. 2. Biology and Ecology of Parenting. Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ.

Marchand, T. H. J. (2003). A Possible Explanation for the Lack Of Explanation; or ‘Why the Master Builder Can’t Explain What He Knows’: Introducing the Informational Atomism Against a ‘Definitional’ Definition of Concepts. In Pottier, J., Bicker, A., and Sillitoe, P. (eds.), Negotiating local knowledge, Pluto Press, London, pp. 30–50.

Merrill, W. L. (1988). Rarámuri Souls: Knowledge and Social Process in Northern Mexico. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington.

Miller, J. (2002). Birthing Practices of the Rarámuri of Northern Mexico. PhD dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson.

Miller, A., and Valencia, B. M. (1999). Barranca Sinforosa Bird Studies: Chihuahua, Mexico (Project # 99-064), vol. 23, Chihuahua.

Nabhan, G., and Trimble, S. (1994). The Geography of Childhood: Why Children Need Wild Places. Beacon, Boston.

Pennington, C. W. (1963). The Tarahumar of Mexico: Their Environment and Material Culture. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.

Postman, N. (1994). The Disappearance of Childhood, 1st Vintage Books edn. Vintage, New York.

Roberts, J. M. (1964). The Self-Management of Cultures. In Goodenough, W. H. (ed.), Explorations in Cultural Anthropology. McGraw-Hill, New York, pp. 433–454.

Romney, A. K., Weller, S. C., and Batchelder, W. H. (1986). Culture as Consensus: A Theory of Culture and Informant Accuracy. American Anthropologist 88: 313–338.

Simpson, B. M. (1994). Gender and the Social Differentiation of Knowledge. Indigenous Knowledge and Development Monitor 2(3).

Stross, B. (1973). Acquisition of Botanical Terminology by Tzeltal Children. In Edmonson, M. S. (ed.), Meaning in Mayan Languages. The Hague, Mouton.

Valsiner, J. (1988). Ontogeny of Co-construction of Culture Within Socially Organized Environmental Settings. In Valsiner, J. (ed.), Child Development Within Culturally Structured Environments: Social Co-construction and Environmental Guidance in Development, Vol. 2. Ablex, Norwood.

Valsiner, J., and Voss, H.-G. (editors) (1996). The Structure of Learning Processes. Ablex, Norwood.

Weller, S. C., and Romney, A. K. (1988). Systematic Data Collection, Vol. 10. Sage, Newbury Park, CA.

Wyndham, F. S. (2002). The Transmission of Traditional Plant Knowledge in Community Contexts: A Human Ecosystem Perspective. In Stepp, J. R., Wyndham, F. S., and Zarger, R. K. (eds.), Ethnobiology and Biocultural Diversity. University of Georgia Press, Athens, pp. 549–557.

Wyndham, F. S. (2004a). Tarahumara. In Ember, C. R., and Ember, M. (eds.), Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender in the World’s Cultures. Vol. 2, Kluwer, New York, pp. 877–884.

Wyndham, F. S. (2004b). Learning Ecology: Ethnobotany in the Sierra Tarahumara, Mexico. PhD dissertation, University of Georgia, Athens.

Wyndham, F. S. (in press). Spheres of Relations, Lines of Interaction: Subtle Ecologies of the Rarámuri landscape in Northern Mexico. Journal of Ethnobiology 29(2).

Zarger, R. K. (2002). Acquisition and Transmission of Subsistence Knowledge by Q’eqchi’ Maya in Belize. In Stepp, J. R., Wyndham, F. S., and Zarger, R. K. (eds.), Ethnobiology and Biocultural Diversity. University of Georgia Press, Athens, pp. 592–603.

Zarger, R. K., and Stepp, J. R. (2004). Persistence of Botanical Knowledge Among Tzeltal Maya Children. Current Anthropology 45(3): 413–418.

Zent, S. (1999). The Quandary of Conserving Ethnobotanical Knowledge: A Piaroa Example. In Gragson, T., and Blount, B. (eds.), Ethnoecology: Knowledge, Resources, Rights. University of Georgia Press, Athens, pp. 90–124.

Zent, S. (2001). Acculturation and Ethnobotanical Knowledge Loss Among the Piaroa of Venezuela. In Maffi, L. (ed.), On Biocultural Diversity: Linking Language, Knowledge, and the Environment. Smithsonian Inst. Press, Washington, DC, pp. 190–211.

Acknowledgements

In Mexico, my deep gratitude goes to the people of Basíhuare and Rejogochi for their guidance and friendship over the years. I am particularly indebted to Moreno Vatista and Margarita León, Silvino León González, Martha Sitánachi, María Elena Lirio and Martín Sanchez, Salomena Ramírez and Efigenia Ramírez, Azucena Zafiro, Roberto Morales González and Julián Morales González, Stanislaus Rascón, Marianita Morales González and Juan Rico León, Felipe Ramírez, Francisco Cardenal, Ubaldo Gardea, Martín Chavez and his family, all my comadres and compadres and ahijados and the Rejogochi and Basíhuare primary schools as well as the secondary school Cruz Rarámuri. At the Instituto Politécnico Nacional of Durango, Mexico thanks to Dra. Socorro González Elizondo for identifying and curating my plant collections. This research was funded by an American Education Research Association/Spencer Foundation Fellowship and grant BCS-0135306 from the National Science Foundation. I thank Brent Berlin, Bill Merrill, Ben Blount, Judith Preissle and Elois Ann Berlin for their comments on an earlier version of this work. The mistakes and shortfalls are all mine. Matéteraba.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wyndham, F.S. Environments of Learning: Rarámuri Children’s Plant Knowledge and Experience of Schooling, Family, and Landscapes in the Sierra Tarahumara, Mexico. Hum Ecol 38, 87–99 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-009-9287-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-009-9287-5