Abstract

A worldwide trend towards high levels of participation in higher education, paired with concerns about the post-university destinations of an increasing pool of graduates, have brought about two parallel phenomena: a process of sharp stratification in higher education and the growing relevance of postgraduate education as undergraduate study becomes nearly ubiquitous, particularly among the most advantaged groups of students. To date, the literature on socioeconomic inequalities and access to higher education has focussed on undergraduate education, with some researchers specifically investigating access to the most prestigious institutions. We contribute to this body of research by investigating the effects of socioeconomic characteristics on access to postgraduate education at those universities believed to deliver elite forms of higher education. We look at access to ‘elite’ postgraduate education among English graduates, operationalised as belonging to the Russell Group of research-intensive universities. We analyse an exceptionally large dataset (N = 533,885) capturing graduate destinations, including postgraduate education at specific institutions. We find that socioeconomic inequalities in attending an elite postgraduate degree persist, but these are mediated by educational variables. Socioeconomically advantaged students are more likely to attain a good degree and to attend an elite institution at the undergraduate level, which powerfully predicts access to elite postgraduate education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Since the mid-twentieth century, participation in higher education in the UK has grown phenomenally. In 1950, fewer than 5% of young people accessed higher education (Marginson, 2018), a figure that reached 60% in 2017 (UNESCO, 2020). This growth has been partially driven by policy discourses that associated increased participation with economic competitiveness and the advancement of social justice (Boliver, 2011; Marginson, 2016). However, an ever-growing corpus of scholarly research has challenged the notion that increased opportunities to access higher education improve the relative chances of disadvantaged pupils to enter higher education and highlights the social class effects on graduates’ labour market outcomes (Shavit et al., 2007; Boliver, 2013; Sullivan et al., 2014; Friedman & Laurison, 2019). In relation to research scrutinising the impact of higher education expansion on social class differences in access, two accounts have been particularly influential: maximally maintained inequality (MMI) (Raftery & Hout, 1993) and effectively maintained inequality (EMI) (Lucas, 2001). These two theoretical accounts have sought to capture the mechanisms by which social class advantage is ‘maintained’ in contexts of expansion. In this sense, Raftery and Hout (1993) suggest that once inequalities reduce at a given level of education as it expands, they emerge at the next educational level. Furthermore, Lucas (2001) argues that inequalities persist as qualitative differences between providers arise at a given expanding educational level, mostly in relation to status (Teichler, 2017).

While both MMI and EMI were developed bearing access to higher education in mind, research has shown that, indeed, different educational levels and differences in status of higher education institutions (HEI) produce different outcomes for their graduates. In this sense, higher education in England is profoundly stratified. English HEIs are substantially different from each other regarding wealth, capacity to attract resources, academic selectivity and the social composition of their student bodies (Boliver, 2015; Raffe & Croxford, 2015; Blackmore, 2016). Most importantly, graduates from English HEIs have significantly different outcomes, with a handful of universities securing access to elite occupations and higher incomes for their students (Wakeling & Savage, 2015; Friedman & Laurison, 2019), who in turn tend to come from wealthy backgrounds (Boliver, 2011, 2013; The Sutton Trust, 2011). However, the relationship between inequalities, access to higher education and graduate outcomes is not limited to status differences between HEIs. These interact with hierarchies of value attached to different subjects of study (Callender & Jackson, 2008; Kim et al., 2015; Van de Werfhorst et al., 2003) and levels of study. Regarding the latter, research shows that postgraduate graduates enjoy better outcomes than do those with a bachelor’s degree or equivalent. For instance, Lindley and Machin (2013) report an annual postgraduate earning premium of £5500, while the Department for Education shows that the median earnings of UK domiciled-students graduating from a taught master’s degree in an English HEI in 2013/2014 were around £29,000, £10,000 more than their undergraduate counterparts (DfE, 2018). A similar relationship also exists in other OECD countries (OECD, 2019). Likewise, Wakeling and Laurison (2017) find that postgraduate degree holders typically attain higher-status occupational positions, with this relationship being consistent over a long period.

Surprisingly, and in spite of the above, there is a lack of research exploring inequalities of access to postgraduate study that considers institutional stratification. Expanding on previous research that investigates the relationship between socioeconomic characteristics and post-graduation destinations of UK graduates (cf. Zwysen & Longhi, 2018; Lessard-Phillips et al., 2018), we focus on the study destinations of English graduates, taking into account the type of HEI they attend at the postgraduate level. First, we review the literature on inequalities and access to postgraduate education. Second, we discuss previous research that had dealt with the stratification of higher education and its impact on socioeconomic inequalities in access, making the case for studying access to postgraduate education in elite institutions in order to investigate its role in social reproduction. Drawing from previous theoretical and empirical research, we then derive a set of empirical expectations that guide the discussion of our findings. Third, we describe the data and methods that we use to explore socioeconomic inequalities in access to elite postgraduate education among English graduates. Fourth, we present our empirical findings, and in the ‘Concluding’ section, we close the article by arguing socioeconomic inequalities in access to elite postgraduate education among English graduates appear to be mediated by academic achievement and the type of institution attended at the undergraduate level.

Inequalities in access to postgraduate education

As with earlier levels of education, studies consistently demonstrate inequalities in access to postgraduate education across various socio-demographic characteristics. In the most general terms, these inequalities are not as marked as in earlier educational transitions; however, in certain transitions and for certain groups, they can be quite stark. We focus here on inequalities across socioeconomic groups.

In the UK, various studies using different measures of socioeconomic background have demonstrated that those from socioeconomically advantaged households have higher rates of transition to postgraduate study than their less advantaged peers. In 2010/2011, Wakeling et al. (2017) found that those from higher managerial and professional backgrounds were 1.4 times more likely than those from routine occupational backgrounds to transition immediately from a first degree to a master’s degree and 2.3 times more likely to progress to a research degree (i.e. Ph.D.). Controlling for academic attainment explains some but not all of this difference (Wakeling, 2017). Wakeling and Laurison (2017) show that these differences have grown over time, in parallel with expansion of access to undergraduate degrees. Using geodemographic measures of socioeconomic background rather than occupational social class, research for government bodies in England (HEFCE, 2016) and Scotland (Scott, 2020) have demonstrated similar patterns. Generally, inequalities are greater for immediate progression to master’s than to Ph.D. (Wakeling, 2017). They are lowest at the point of immediate transition after a first degree and get larger if measured for delayed transitions (d’Aguiar & Harrison, 2016; HEFCE, 2016; Wakeling, 2017).

While they remain relatively under-researched, similar general trends by socioeconomic background are found across all countries where studies have been conducted, including USA (Mullen et al., 2003; Posselt & Grodsky, 2017; Pyne & Grodsky, 2020), Germany (Neugebauer et al., 2016), Norway (Mastekaasa, 2006), Australia (Department of Education Australia, 2019) and various European countries for doctoral study (Triventi, 2013). There is evidence that some of the differences observed across socioeconomic background are related to the distribution of students from different socioeconomic backgrounds across institutions of different status. Those from higher-status institutions are more likely to progress to postgraduate study and are also more likely to be from the more socioeconomically advantaged groups (Scott, 2020; Department of Education Australia, 2019; Wakeling, 2017). Although they are not our focus in this article, evidence also suggests inequalities in postgraduate participation by race/ethnicity, in the UK (Wakeling et al., 2017; Williams et al., 2019) and other Anglophone countries (McCallum et al., 2017; Moodie et al., 2018).

Notwithstanding, most of the research on access to postgraduate education, while considering the status of institutions at the undergraduate level, does not take into account the positions of institutions attended by graduate students. Indeed, if we observe that graduate outcomes vary substantially depending on the type of institution attended at the undergraduate level, a working hypothesis is that this is also the case at the postgraduate level. In the following section, we review the literature that considers socioeconomic inequalities in access to high-status institutions.

Inequalities and the stratification of higher education

There is a burgeoning corpus of research tackling the role of qualitative differences between education providers in reproducing socioeconomic inequalities in access, experiences and labour market outcomes of students (Shavit et al., 2007; Mullen, 2009; Boliver, 2011; Binder & Abel, 2019). This research, consistent with Lucas’ (2001) ‘effectively maintained inequality’ thesis, supports the idea that socioeconomically advantaged families try to secure better types of education for their children, particularly in contexts of expansion. As Arum et al. (2007, p. 1) suggest, the expansion of higher education ‘has been accompanied by differentiation. Systems that had consisted almost exclusively of research universities developed second-tier and less selective colleges’, and most of the expansion happened, particularly among non-traditional students, in these less selective institutions. This is especially true of the UK. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, fostered by a ‘renewed political commitment to higher education expansion’ (Boliver, 2011, p. 233) and the upgrading of the former polytechnics to the title of university in 1992 (Shattock, 2012), higher-education enrolments in the UK increased dramatically. This expansion of both enrolments and the number of institutions with a university title brought about an explicit drive for differentiation, as the status differentials and disparities in the outcomes of their graduates persist between those universities founded before 1992 and the new set of universities (Bathmaker et al., 2013). A good example of this drive can be found in the first Times Good University Guide, published in 1993 (O’Leary & Cannon, 1993). In the preface of the latter publication, the authors stated ‘[…] the existence of more than 90 diverse universities and an ever-growing pool of graduates will make a pecking order inevitable’ (O’Leary & Cannon, 1993, p.3). In the UK, this drive for differentiation was translated into a very British ‘club strategy’, as expressed by Scott (1995, p. 52). He adds that

the pressure to create an elite sector, able to compete globally, [was] reflected in the emergence of an informal grouping of the vice-chancellors of Oxford, Cambridge, the main London college and the big civics, the so-called “Russell Group”’ (ibid.), which is now used as a category of prestige in UK higher education. Other groupings followed, known as ‘mission groups’, which sought to establish distinctive institutional identities based on, roughly speaking, similar origins, ethos and ambitions (Scott, 2013).

In the UK, various studies have shown a stark relationship between students’ socioeconomic characteristics and access to undergraduate degrees in institutions at the top of this ‘pecking order’. Boliver (2011) showed that between the 1960s and the 1990s, the probability of working-class students accessing an ‘old’ university—considered as a marker of prestige—remained persistently lower than for more well-off students. Similarly, Sullivan and colleagues (Sullivan et al., 2014) found that students attending a private secondary school were substantially more likely to gain a degree from a ‘Russell Group’ institution even when controlling for cognitive characteristics and academic achievement. Evidence suggests that this phenomenon exists elsewhere and in lower levels of education. A comparative study analysing the effect of socioeconomic characteristics on academic performance and types of secondary education attended in 17 countries showed that regardless of the nature of qualitative differences in secondary school systems, privileged families ‘seem to rely on qualitative differences within school systems to place their children in the “right” environment that guarantee better instruction and more successful educational trajectories’ (Triventi et al., 2019, p. 12). In the case of higher education, several researchers have also found a significant relationship between socioeconomic characteristics and type of university attended in Greece (Sianou-Kyrgiou, 2010), France and Germany (Duru-Bellat et al., 2008), the USA (Alon, 2009) and Ireland (McCoy & Smyth, 2010). Furthermore, Triventi (2013), in a comparative study looking at the relationship between the stratification of higher education and social inequality in 11 European countries, found that in most countries, parental education was correlated with undergraduate study at a prestigious institution.

Drawing together the theoretical accounts and empirical observations outlined above, we can derive some expectations for the empirical patterns we might observe in postgraduate participation for English graduates. If inequality is maximally maintained, differences will be observed between graduates from advantaged and disadvantaged social classes in their rates of transition to postgraduate study in general, net of other factors, but there will be no social class differences in access to elite postgraduate education. If it is effectively maintained, then no differences will be observed between graduates from advantaged and disadvantaged social classes in their rates of transition to postgraduate study, net of other factors, but there will be clear social class differences in access to elite postgraduate education. Inequality may also be institutionally stratified. Net of other factors, including social class, graduates attending elite undergraduate institutions will have a clear advantage in accessing elite postgraduate education.

Data and methods

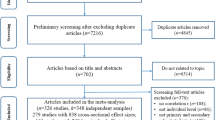

We analyse a bespoke dataset from the UK’s Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) student record, containing socioeconomic and educational information of all English-domiciled undergraduate leavers who graduated from a UK higher-education institution in the academic years 2015/2016 and 2016/2017 (N = 533,885). These data are linked to HESA’s Destinations of Leavers from Higher Education (DLHE) survey, which registers graduates’ activity approximately 6 months after graduation, including further study. Thus, we are able to explore patterns of progression to postgraduate study for those students who finished an undergraduate degree and enrolled in postgraduate programme in the academic years 2016/2017 and 201720/18. This dataset also allows us to explore which kind of postgraduate degree these students started and at which higher education institution.

The DLHE survey aims to be a census. While it does not achieve this ambition, the resulting response rates are very high (on average 77.8% in the 2 years in question). This means that we have complete enumeration of the first-degree graduates but miss graduate outcome data for those who did not respond to the survey. We used poststratification inverse probability weighting to adjust for this survey non-response. We fitted a saturated model to predict survey non-response using the known information as predictors. This generates a predicted probability of survey response for each unique combination of graduate characteristics, the reciprocal of which is used to weight survey responses, on an assumption that data is missing at random (Gelman & Carlin, 2002).

The reason why we constrain our population to those graduates domiciled in England who finished their undergraduate education in 2015/2016 at the earliest is the current support schemes for postgraduate students that exist in the UK, which differ across home nations. In the UK, higher-education policy is a devolved competence, and as such, the funding available to support postgraduate education, and the years this support was introduced, varies across the four constituent UK ‘home nations’. England was the first home nation to introduce a non-means tested student loan package for those students starting a master’s degree in 2016/2017, which allowed students to borrow £10,000—a quantity that increases every year with inflation—to pay for tuition and maintenance (Hubble et al., 2018). Other home nations followed suit in the next academic year but with different loan levels available (Mateos-González & Wakeling, 2020), an issue that is likely to produce different progression rates to postgraduate education across UK home nations.

The list of variables used in this paper can be found in Table 1 of the Appendix. Our dependent variable measures the postgraduation destinations of English graduates, including type of further study by type of institution attended. HESA provides a variable that identifies the type of qualification sought after graduation, which we have grouped into four categories: (1) Higher degree, taught (e.g. MA, MSc, MBA), (2) Higher degree, research (e.g. PhD, DPhil, MPhil),Footnote 1 (3) Other (including postgraduate diplomas or certificates, and professional qualifications) and (4) Not studying (i.e. working, due to start work or unemployed). We considered grouping together the categories Higher degree, taught and Higher degree, research—and we did run our models with these two categories merged, but the effect on the results was negligible—but we believe that theoretically speaking, these two categories should to be kept separate. First, HESA does not distinguish between a master’s degree by research, which ‘are examined by research whilst not requiring candidates to produce research of sufficient weight to merit a doctoral qualification’ (House, 2020, p. 6), and doctoral qualification, both included under the label Higher degree, research. This means that grouping both categories together would add even more heterogeneity to Higher degree, taught programmes, which already ‘vary enormously in terms of their function and intended outcomes’ (House, 2020, p. 5). Second, we also believe that the motivations of students enrolled in either category may have substantially different motivations. For most students, a Higher degree, taught programme will be the last time they experience higher education, with the hope of transforming this qualification into an advantage in the labour market. However, in the case of research degrees, it is reasonable to assume that most students are more academically oriented.

Following the definition of the categories that capture graduates’ educational destinations, we have combined the first two values of the dependent variable with one that measures type of institution attended. We have decided not to separate the value Other by type of institution attended as we judged that institutional hierarchies are unlikely to have the same relevance for these types of qualifications than for master’s and Ph.D.s. The category ‘other qualifications’ is heterogeneous, including courses of varying lengths and purposes. To measure elite universities, we have used the Russell Group of 24 institutions, which is commonly used in the literature to identify elite UK universities (Lessard-Phillips et al., 2018; Sullivan et al., 2014, 2018). We considered more granular classifications of UK universities that take into account differences within the Russell Group—for instance, recognising the exceptionality of Oxford and Cambridge and a handful of London institutions—but the analysis yielded numbers that were judged to be too small for robust analysis, an issue that was also identified by Sullivan et al. (2014) when analysing the 1970 British Cohort Study.

Our main independent variable of interest is social class, which is measured by using the UK government’s interpretation of the Erikson-Goldthorpe-Portacero socioeconomic classification of the reference occupation for the graduates’ household (Rose et al., 2005), known as NS-SEC. For students in our dataset, NS-SEC is recorded when entering higher education at the undergraduate level. We also include an array of socioeconomic and educational variables, namely: ethnicity, sex, whether undergraduate degree was an integrated master’s, qualifications at entry to higher education, first-degree grade, type of undergraduate institution and subject of study at undergraduate level.Footnote 2 Subject of study is measured using a classification developed by Purcell and colleagues (Purcell et al., 2009), which derives from empirically observed differences of graduates’ aspirations and outcomes across the following four areas: STEM; Law, Economics and Management; non-STEM academically focused degrees and vocationally focused degrees. A description of these variables can be found in Table 1 of the Appendix.

We use multinomial logistic regression to model the probabilities of progressing to each category of our dependent variable. Our modelling strategy starts with a model that contains only socioeconomic variables—NS-SEC, ethnicity and sex—producing 5 subsequent models adding one educational variable at a time.Footnote 3 This has allowed us to understand changes in the effect of social class on progressing to postgraduate study in an elite university when controlling for particular educational characteristics. In this sense, we report the models’ pseudo R-squared, an effect size measure that is particularly useful when assessing the performance of different logistic regression models on the same data (Long 1997). We report our coefficients using average marginal effects (AMEs), which ‘can be interpreted as the extent to which the predicted probabilities of membership in a specific response category differ on average for individuals’ from each independent variable category relative to the reference category’ (Lessard-Phillips et al., 2018, p. 501).

Results

In this section, we describe our findings, which allow us to understand the extent to which social class affects progression to an elite postgraduate degree, taking into account other socioeconomic and educational variables and asses, in the ‘Discussion’, our theoretical expectations. Figure 1 reports the totals and percentages of graduates in each NS-SEC class that progressed to a taught higher degree and a research higher degree by type of institution roughly 6 months after graduation.Footnote 4 Here, we have not included an equivalent graph for those graduates that progressed to a form of education categorised as Other, as socioeconomic differences were minimal. We have also omitted the graph displaying the percentage of graduates that were ‘not studying’—there are differences across socioeconomic groups, but these are already explained in Fig. 1.

First, in Fig. 1a, we observe that there appear to be few differences in overall progression rates to higher taught degrees between NS-SEC categories, with the exception of those graduates who come from ‘never worked’ backgrounds. Graduates from this background were 2 percentage points more likely to progress to a higher taught degree than their ‘higher managerial’ counterparts. However, when we look at graduates who progressed to a higher taught degree at a Russell Group university, this picture looks quite different. We observe that almost 6% of graduates from higher managerial backgrounds made this transition, 3 and 4 percentage points higher than their routine and never worked counterparts respectively. We also see that the probability of attending a Russell Group HEI for a higher taught degree reduces progressively along with NS-SEC categories. Second, in Fig. 1b, we observe that all NS-SEC classes have lower rates of overall progression to higher degree by research than graduates from higher managerial backgrounds, and these percentages reduce along NS-SEC classes, with the exception of students from ‘lower supervisory’ backgrounds. It also shows that, at this level of education, graduates tend to concentrate in the research-intensive Russell Group, although this concentration is lower among graduates from lower supervisory, ‘semi-routine’ and routine backgrounds.

As stated in the “Data and methods” section, we have carried out a modelling strategy starting with a multinomial logistic regression model that includes only socioeconomic variables and producing 5 subsequent models adding one educational variable at a time. In order to compare the performance of each model and understand the value added of each of the characteristics of the educational trajectories of our respondents, we have produced and compared the pseudo R-squared for each model, found in Table 4 of the Appendix. Regarding the pseudo R-squared values, the model that has the best performance is, unsurprisingly, model 6, which contains all independent variables (pseudo R-squared = 0.09). Conversely, model 1, which contains only socioeconomic variables, has a pseudo-R-squared of 0.01. It is worth mentioning that all the educational variables progressively added to each of the models make a positive contribution to the models’ performance.

Considering the performance of our models, we describe in detail the coefficients—reported as AMEs—of the first model and the best-performing model to understand the role that graduates’ NS-SEC background has on their probabilities of accessing a postgraduate course in Russell Group institution, controlling for their educational trajectories. In this section, we report the AMEs produced by these two models for NS-SEC categories graphically. The full model tables can be found in Tables 2 and 3 of the Appendix. Moreover, in order to understand the value added of each educational variable to the probability of graduates to progress to a postgraduate course by NS-SEC category, we report the AMEs produced by each of the 6 models—and their pseudo R-squared—in Table 4 of the Appendix.

Figure 2 displays the AMEs of NS-SEC classes—reference category: ‘Higher managerial‘—produced by our first model, a multinomial logistic regression model predicting postgraduate destinations using socioeconomic variables only, including ethnicity and sex.

This figure reports the differences in the predicted probabilities of being in each category of the dependent variable for each NS-SEC class compared with the highest social class. The AMEs located to the left of the line indicate a lower predicted probability than higher managerial, while those found to the right indicate a higher probability. We observe that the predicted probabilities of progressing to a taught higher degree in a Russell Group university decreases through NS-SEC classes, with students from routine and never worked backgrounds being 3 and 4 percentage points less likely to progress than their higher managerial counterparts. This difference is substantial considering that in our dataset, only 4% of graduates progressed to a taught higher degree in a Russell Group university. We observe the opposite trend for those graduates transitioning to a taught higher degree at a non-Russell Group university: routine and never worked students were 3 and 5 percentage points more likely to do so. In relation to progressing to a higher degree by research at a Russell Group university, Fig. 3 reports that all NS-SEC classes are approximately 1 percentage point less likely to do so than the reference category, whereas the differences of doing so at a non-Russell Group university are negligible. Finally, we also observe differences in the predicted probabilities of pursuing other further study or not being in further study; NS-SEC classes other than higher managerial tend to be less likely to pursue other study and more likely to report not being in further study.

Figure 3 reports the AMEs for NS-SEC classes, controlling for socioeconomic and all educational variables.

Here, we observe that the effect of social class on progression to a taught higher degree in a Russell Group university wanes when adding our educational variables, suggesting that social class effects are mediated by academic achievement and attainment. In Table 4 of the Appendix, we can see the effect of each educational variable—added progressively at each of the 6 models—on the AMEs for NS-SEC categories. We can observe that there are two variables that clearly reduce the effect of NS-SEC membership on the probability of progressing to a postgraduate degree at a Russell Group university: UCAS tariff and type of HEI. We discuss the implications of this in the “Discussion” section.

The addition of educational variables to our models substantially reduces the effect of social class on progression to a taught higher degree in a Russell Group university and disappear almost entirely when predicting progression to a research degree or to other types of further study. This suggests that social class effects are mediated by academic achievement and attainment when entering university. In terms of the effect of different educational variables, in Table 3 of the Appendix, we observe that those students who graduated from a bachelor’s degree with a master’s component (integrated master’s) are 4 and 7 percentage points less likely to progress to taught higher degree in a Russell Group and a non-Russell Group university respectively, which is unsurprising. Equally unsurprisingly, they are also more likely to progress to a higher degree by research, which usually requires a master’s degree.

Prior academic achievement and type of institution attended at the undergraduate level appear to be the strongest predictors of progression to different types of postgraduate study at different types of institutions. First, graduates with the highest possible undergraduate mark (first-class honours) are 2 percentage points more likely to progress to a taught higher degree in a Russell Group university, and these differences turn negative at lower levels of achievement. This effect can also be observed for those graduates progressing to a taught higher degree at a non-Russell Group university. Second, the type of institution attended at the undergraduate level appears to be particularly important. These results suggest that once a student enters a type of institution, their later educational trajectories become tracked. Those graduates attending a Russell Group university at the undergraduate level are 6 percentage points more likely to attend one for a taught higher degree. Contrariwise, graduates from non-Russell Group institutions are 7 percentage points more likely to do so in the same type of institution.

Finally, the subject of study pursued at the undergraduate level also has an important effect. Expectedly, those graduates from vocational subjects are less likely to progress to a taught higher degree than the reference category (STEM), presumably because their qualifications have a more direct articulation with the labour market. It is also not surprising that graduates from Law, Economics and Management subjects (LEM) are more likely to pursue other further study, as these include professional qualifications required for professional practice.

Discussion

Beginning with the expectations we established derived from relevant sociological theory, how far do our findings conform? The bivariate relationship between social class and transition to (elite) postgraduate research study points to maximally maintained inequality: at this highest—and rarest—educational progression point, social class differences remain among graduates. For taught postgraduates, there are only minor social class differences in overall transition, but clear differences in progression to institutions of different status, consistent with the effectively maintained inequality thesis. Once educational variables such as first-degree attainment, first-degree subject discipline and first-degree institution are considered, direct social class inequalities dissipate. First-degree institution appears to be particularly important, leaving an abiding impression of institutional stratification. There are considerable inequalities in initial access to first degrees in universities of differing status; thereafter, graduates tend to ‘stay in their lane’ during their postgraduate transitions. This means that we observe sustained rather than intensified EMI in the case in question. There are strong echoes here of much older research on the previously tracked English ‘tripartite’ schooling system which selected pupils into ‘grammar school’ and ‘secondary modern’ tracks, aged 11. Researchers found very sharp social class differences in entry to the more prestigious grammar schools but much smaller differences across social class in grammar pupils’ outcomes. The problem was that few working-class pupils entered grammar school (Halsey et al., 1980). Likewise, here, we see the institution attended at first-degree level plays a substantial role in accounting for social class differences in immediate progression to postgraduate study, with class differences much smaller when controlling for institution of first degree. However, far fewer working-class students attend Russell Group universities (Boliver, 2013).

Institutional tracking might imply that policy should focus, as it often has at undergraduate level in England, on ‘widening participation’ to elite universities at undergraduate level, on the basis that if graduates ‘stay in lane,’ there will be a consequent flow through disadvantaged graduates to master’s and doctoral study in elite universities. The problem here is that such changes would do nothing to reduce—and risk reifying—the problem of institutional stratification itself. This is analogous to broader discussions about social mobility. Selecting a chosen few from the working-class for long-range upward mobility does not alter the system, and some would argue it reinforces the system as fair.

Thinking more broadly, what message do these results from England send about continuing inequality in the transition to postgraduate study? We suggest that the message is a little mixed. There are certainly some positive signals hinting at reduced inequality. We found little apparent evidence of systematic ‘trading up’ of institutional status by advantaged students between levels, such as is seen in earlier stages of the English educational system (Bathmaker et al., 2013; Boliver, 2011) and in the behaviour of the relatively small group of English students who opt to study for a full degree in another country (Brooks & Waters, 2009). Following the extension of student loans to master’s level, it would also appear that, compared with earlier transitions, social class differences in postgraduate progression substantially reduce, suggesting the appearance of ‘meritocratic’ progression. Previous research by (Mateos-González & Wakeling, 2020) has shown that the introduction of master’s loans in England has widened the participation of less well-off students in postgraduate education. Indeed, some disadvantaged groups have marginally higher rates of progression than their more advantaged counterparts.

Other elements of the patterns observed are more troubling. While we do not find strong evidence of inequality getting worse on the basis of social class at postgraduate level, nor is there any correction to previous inequality. Our evidence shows that those from disadvantaged social class backgrounds are only slightly less likely to progress to a master’s degree than their advantaged peers, but this means that they remain an underrepresented group at postgraduate level. Differences in progression are starker in progression to a research degree but reduce considerably once educational variables are accounted for. While this suggests that increasing the end-of-degree attainment among disadvantaged social classes would tend towards equalising progression chances, it remains the case that these groups are underrepresented among doctoral students. Nevertheless, our findings here reflect those of recent studies elsewhere. Torche (2018) found only very small associations between socioeconomic background and outcomes for Ph.D. holders in the USA; Hu et al. (2020) found differences in test scores among graduates in Beijing accounted for observed socioeconomic differences in entry rates.

Finally, our findings point to avenues for further research. We suggest four in particular. To complete our understanding of the place of postgraduate qualifications from different universities in social mobility, we need a more granular understanding of outcomes for graduates of different kinds of postgraduate qualifications from universities of differing status. Second, we need to understand graduates’ subjective decision-making processes in relation to seeking postgraduate study and choosing institutional location. Third, we need to investigate the role of institutional stratification at postgraduate level within different domestic systems and internationally. Fourth, we need to understand other dimensions of inequality in postgraduate participation, such as by gender and race/ethnicity, but where the pertinent mechanisms are likely to differ from those for social class inequalities.

While postgraduate qualifications are, perhaps inevitably, a minority pursuit, their importance for securing advantaged positions is more important now than ever before. Moreover, the holders of postgraduate qualifications provide the pool from which the experts of the future are drawn. As 2020 has shown, knowledge and expertise are critical for addressing the challenges of our time, and we therefore need to ensure a route to expertise which is as wide and inclusive as possible.

Data Availability

The data provider does not allow sharing the data.

Notes

We have excluded from our analysis those graduates who progressed to a higher degree, taught or by research, with missing information about their postgraduate institution. For our independent variables, we have included cases with missing values (e.g. ‘Unknown’ or ‘Not applicable’), but we do not report their regression estimates. To check for robustness, we ran the models excluding the cases with missing values in our independent variables, and the differences were negligible.

We tested for multicollinearity by calculating the variance inflation factor (VIF), which allows to determine whether there is a strong linear relationship between independent variables. Conventionally, it is believed that if VIF scores are higher than 10, this linear relationship exists (Stevens, 2009). Our VIF values ranged between 1.03 and 1.18, with a mean VIF value of 1.09, suggesting that multicollinearity is not a problem in our models.

We also considered introducing interaction effects between our socioeconomic and educational variables. Thus, we run our models including interaction terms between type of undergraduate institution, gender and NS-SEC, but we decided to exclude them as they did not improve the goodness-of-fit measures of our models.

References

Alon, S. (2009). The evolution of class inequality in higher education. American Sociological Review, 74(5), 731–755.

Arum, R., Gamoran, A., & Shavit, Y. (2007). More inclusion than diversion: Expansion, differentiation, and market structure in higher education. In Y. Shavit, R. Arum, & A. Gamoran (Eds.), Stratification in higher education. A comparative study (pp. 1–37). Stanford University Press.

Bathmaker, A. M., Ingram, N., & Waller, R. (2013). Higher education, social class and the mobilisation of capitals: Recognising and playing the game. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 34(5–6), 723–743.

Binder, A. J., & Abel, A. R. (2019). Symbolically maintained inequality: How Harvard and Stanford students construct boundaries among elite universities. Sociology of Education, 92(1), 41–58.

Blackmore, P. (2016). Prestige in academic life. Excellence and Exclusion. Routledge.

Boliver, V. (2011). Expansion, differentiation, and the persistence of social class inequalities in British higher education. Higher Education, 61(3), 229–242.

Boliver, V. (2013). How fair is access to more prestigious UK universities? British Journal of Sociology, 64(2), 344–364.

Boliver, V. (2015). Are there distinctive clusters of higher and lower status universities in the UK? Oxford Review of Education, 41(5), 608–627.

Brooks, R., & Waters, J. (2009). A second chance at ‘success’ UK students and global circuits of higher education. Sociology, 43(6), 1085–1102.

Callender, C., & Jackson, J. (2008). Does the fear of debt constrain choice of university and subject of study? Studies in Higher Education, 33(4), 405–429.

Department for Education (DfE). (2018). Graduate Outcomes (LEO): Postgraduate Outcomes in 2015 to 2016. Department for Education.

Department of Education Australia. (2019). Student equity in higher degrees by research: Statistical report August 2019. Department of Education.

Duru-Bellat, M., Kieffer, A., & Reimer, D. (2008). Patterns of social inequalities in access to higher education in France and Germany. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 49(4–5), 347–368.

d’Aguiar, S., & Harrison, N. (2016). Returning from earning: UK graduates returning to postgraduate study, with particular respect to STEM subjects, gender and ethnicity. Journal of Education and Work, 29(5), 584–613.

Friedman, S., & Laurison, D. (2019). The class ceiling: Why it pays to be privileged. Policy Press.

Gelman, A., & Carlin, J. B. (2002). Poststratification and weighting adjustments. In D. A. Dillman, J. L. Eltinge, & R. J. A. Little (Eds.), Survey Nonresponse (pp. 289–302). Wiley.

Halsey, A. H., Heath, A. F., & Ridge, J. M. (1980). Origins and destinations: Family, class and education in modern Britain. Clarendon Press.

HESA (2021). Rounding and suppression to anonymise statistics. https://www.hesa.ac.uk/about/regulation/data-protection/rounding-and-suppression-anonymise-statistics. Accessed 22 Jan 2021.

Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE). (2016). Transitions into postgraduate study. Higher Education Funding Council for England.

House, G. (2020). Postgraduate education in the United Kingdom. Higher Education Policy Institute and The British Library.

Hubble, S., Foster, D. & Bolton, P. (2018). Postgraduate loans in England (House of Commons Library No. 7049). London: House of Commons Library. Retrieved May 7, 2020, from https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn07049/.

Hu, A., Kao, G., & Wu, X. (2020). Can greater reliance on test scores ameliorate the association between family background and access to post-collegiate education? Survey evidence from the Beijing College Students Panel survey. Social Science Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2020.102425.

Kim, C. H., Tamborini, C. R., & Sakamoto, A. (2015). Field of study in college and lifetime earnings in the United States. Sociology of Education, 88(4), 320–339.

Lessard-Phillips, L., Boliver, V., Pampaka, M., & Swain, D. (2018). Exploring ethnic differences in the post-university destinations of Russell Group graduates. Ethnicities, 18(4), 496–517.

Lindley, J., & Machin, S. (2013). The postgraduate premium. Revisiting trend in social mobility and educational inequalities in Britain and America. The Sutton Trust.

Long, J. S. (1997). Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Lucas, S. R. (2001). Effectively maintained inequality: Education transitions, track mobility, and social background effects. American Journal of Sociology, 106(6), 1642–1690.

Marginson, S. (2016). High participation systems of higher education. Journal of Higher Education, 87(2), 243–271.

Marginson, S. (2018). Global trends in higher education financing: The United Kingdom. International Journal of Educational Development, 58, 26–36.

Mastekaasa, A. (2006). Educational transitions at graduate level: Social origins and enrolment in PhD programmes in Norway. Acta Sociologica, 49(4), 437–453.

Mateos-González, J. L., & Wakeling, P. (2020). Student loans and participation in postgraduate study: The case of English master’s loans. Oxford Review of Education, 46(6), 698–716.

McCallum, C. M., Posselt, J. R., & López, E. (2017). Accessing postgraduate study in the United States for African Americans: Relating the roles of family, fictive kin, faculty, and student affairs practitioners. In A. Mountford-Zimdars & N. Harrison (Eds.), Access to Higher Education: Theoretical Perspectives and Contemporary Challenges (pp. 171–189). Routledge and Society for Research into Higher Education.

McCoy, S., & Smyth, E. (2011). Higher education expansion and differentiation in the Republic of Ireland. Higher Education, 61(3), 243–260.

Moodie, N., Ewen, S., McLeod, J., & Platania-Phung, C. (2018). Indigenous graduate research students in Australia: A critical review of the research. Higher Education Research and Development, 37(4), 805–820.

Mullen, A. L. (2009). Elite destinations: Pathways to attending an Ivy League university. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 30(1), 15–27.

Mullen, A. L., Goyette, K. A., & Soares, J. A. (2003). Who goes to graduate school? Social and academic correlates of educational continuation after college. Sociology of Education, 76(2), 143–169.

Neugebauer, M., Neumeyer, S., & Alesi, B. (2016). More diversion than inclusion? Social stratification in the Bologna system. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 45, 51–62.

O’Leary, J., & Cannon, T. (1993). The Times Good Universities Guide. Times Books.

OECD (2019). OECD Statistics: Education and Earnings. https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=EAG_EARNINGS#. Accessed 13 June 2019.

Posselt, J. R., & Grodsky, E. (2017). Graduate education and social stratification. Annual Review of Sociology, 43(1), 353–378.

Purcell, K., Elias, P. & Atfield, G. (2009). Analysing the relationship between higher education participation and educational and career development patterns and outcomes. A new classification of higher education institutions. Futuretrack. Higher Education Careers Services Unit Working Paper 1.

Pyne, J., & Grodsky, E. (2020). Inequality and opportunity in a perfect storm of graduate student debt. Sociology of Education, 93(1), 20–39.

Raffe, D., & Croxford, L. (2015). How stable is the stratification of higher education in England and Scotland? British Journal of Sociology of Education, 36(2), 313–335.

Raftery, A. E., & Hout, M. (1993). Maximally maintained inequality: Expansion, reform, and opportunity in Irish education, 1921–1975. Sociology of Education, 66(1), 41–62.

Rose, D., Pevalin, D. J., & O’Reilly, K. (2005). The national statistics socio-economic classification: Origins, development and use. Palgrave Macmillan.

Scott, P. (1995). The meanings of mass higher education. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Scott, P. (2013). University mission groups: What are they good for? Newspaper article. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2013/mar/04/university-missiongroups-comment#. Accessed 14 April 2020.

Scott, P. (2020). Access to postgraduate study: Representation and destinations. Scottish Government - Commissioner for Fair Access.

Shattock, M. (2012). Making Policy in British Higher Education 1945–2011. Open University Press.

Shavit, Y., Arum, R., & Gamoran, A. (2007). Stratification in higher education: A comparative study. Stanford University Press.

Sianou-Kyrgiou, E. (2010). Stratification in higher education, choice and social inequalities in Greece. Higher Education Quarterly, 64(1), 22–40.

Stevens, J. P. (2009). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences (5th ed.). New York: Routledge.

Sullivan, A., Parsons, S., Wiggins, R., Heath, A., & Green, F. (2014). Social origins, school type and higher education destinations. Oxford Review of Education, 40(6), 739–763.

Sullivan, A., Parsons, S., Green, F., Wiggins, R., & Ploubidis, G. (2018). Elite universities, fields of study and top salaries: Which degree will make you rich? British Educational Research Journal, 44(4), 663–680.

The Sutton Trust. (2011). Degrees of success: university chances by individual school. Sutton Trust.

Teichler, U. (2017). Higher education system differentiation, horizontal and vertical. In J. Shin & P. Texeira (Eds.), Encyclopedia of International Higher Education Systems and Institutions. Springer.

Torche, F. (2018). Intergenerational mobility at the top of the educational distribution. Sociology of Education, 91(4), 266–289.

Triventi, M. (2013). Stratification in higher education and its relationship with social inequality: A comparative study of 11 European countries. European Sociological Review, 29(3), 489–502.

Triventi, M., Skopek, J., Kulic, N., Buchholz, S., & Blossfeld, H. P. (2019). Advantage ‘finds its way’: How privileged families exploit opportunities in different systems of secondary education. Sociology, 1, 1–21.

UNESCO (2020). United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. UNESCO Institute of Statistics. http://uis.unesco.org/country/GB. Accessed 17 March 2020.

Van De Werfhorst, H. G., Sullivan, A., & Cheung, S. Y. (2003). Social class, ability and choice of subject in secondary and tertiary education in Britain. British Educational Research Journal, 29(1), 41–62.

Wakeling, P. (2017). A glass half full? Social class and access to postgraduate study. In R. Waller, N. Ingram, & M. R. M. Ward (Eds.), Higher Education and Social Inequalities: University Admissions, Experiences, and Outcomes (pp. 167–189). Routledge.

Wakeling, P., Hampden-Thompson, G., & Hancock, S. (2017). Is undergraduate debt an impediment to postgraduate enrolment in England? British Education Research Journal, 43(6), 1149–1167.

Wakeling, P., & Laurison, D. (2017). Are postgraduate qualifications the ‘new frontier of social mobility’? British Journal of Sociology, 68(3), 533–555.

Wakeling, P., & Savage, M. (2015). Entry to elite positions and the stratification of higher education in Britain. Sociological Review, 63(2), 290–320.

Williams, P., Bath, S., Arday, J., & Lewis, C. (2019). The broken pipeline: Barriers to black PhD students accessing research council funding. Leading Routes.

Zwysen, W., & Longhi, S. (2018). Employment and earning differences in the early career differences of ethnic minority British graduates: The importance of university career, parental background and area characteristics. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies,44(1), 154–172.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mateos-González, J.L., Wakeling, P. Exploring socioeconomic inequalities and access to elite postgraduate education among English graduates. High Educ 83, 673–694 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00693-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00693-9