Abstract

Universities in many countries increasingly value talent, and do so by developing special honors programs for their top students. The selection process for these programs often relies on the students’ prior achievements in school. Research has shown, however, that school grades do not sufficiently predict academic success. According to Renzulli’s (1986) three-ring model, student characteristics relating to intelligence, motivation and creativity are the most important predictors of excellent achievements in professional life. In this paper, we will investigate whether honors students differ from non-honors students in terms of these characteristics. By means of a questionnaire, more than 1,100 honors and non-honors students at Utrecht University were asked to assess themselves on six characteristics: intelligence, creative thinking, openness to experience, the desire to learn, persistence, and the drive to excel. The results showed that the honors students differed significantly from the non-honors students in terms of the combined variables as well as for the separate variables, with the exception of ‘persistence’. The strongest distinguishing factors between honors and non-honors students appeared to be the desire to learn, the drive to excel and creativity, whilst there was little difference in terms of intelligence and persistence. However, the profiles of these differences varied according to the study program. While Law and Humanities honors students differed from their non-honors peers in terms of their drive to excel, Physics honors students were primarily more eager to learn than their non-honors peers, while the LA&S honors students scored higher on creative thinking than non-honors students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Universities in many countries increasingly value talent, and do so by developing special honors programs for their top students. The objective of these programs is to provide opportunities for students to develop their talents to the full, enabling them to make significant contributions to science and society. Honors students are assumed to have the potential to excel in their future professional lives. It is, however, unclear whether and to what extent these honors students do indeed have this potential in comparison to non-honors students. In contrast with the huge body of research on giftedness in primary and secondary education, empirical research on talent in higher education is surprisingly scarce (Achterberg 2005; Clark 2000; Long and Lange 2002; Rinn and Plucker 2004). This is remarkable given the growth of programs specifically designed for groups of students who are assumed to be academically talented. Universities often select honors students based on their grades in secondary education and their level of motivation. In his review of the relationship between grades attained at school or at university and adult accomplishment, Hoyt (1966) concluded that grades have hardly any relationship with any measure of future achievement. Twenty years later, Cohen (1984) found similar results in his meta-analysis, indicating that the predictive value of grades for professional success is small. Taylor et al. (1985) came to the same conclusion, demonstrating that grades and standardized tests can predict future grades, but that they do not predict professional excellence. High school grade point averages (GPAs) are used as predictors, as well as scores on scholastic aptitude tests (SATs) and letters of recommendation (Rinn and Plucker 2004). The area of the selection process, which is based on motivation, can be either active, by means of letters and interviews, or passive, relying on the self-selection of the students.

However, it is questionable whether it is safe to trust these selection methods. We do not know whether these selection methods supply honors programs with students who are significantly more motivated than non-honors students are. Furthermore, not all of the students who are qualified apply for the honors program or college, and a number of them end up in regular programs. Thus, even if application forms, letters, and interviews are used as evidence of motivation, we cannot know whether honors students are more motivated than their non-honors peers.

This study investigates whether honors students differ from non-honors students with respect to qualities that have been found to be essential for exceptional accomplishments in professional life. Further, we examine which of these qualities primarily differentiate between honors and non-honors students.

Empirical evidence regarding the specific qualities of honors students is needed if honors programs are to be able to judge whether they have selected the right students, to match their programs to the qualities of the students, and to justify their existence. In order to comprehend what the important factors are, we directed our attention to literature regarding excellent professionals. As honors programs are designed to encourage potential innovative professionals to bloom, it is reasonable to search for aptitudes and personality traits that are required for making creative contributions to a professional domain in adult life. The body of research derived from retrospective and longitudinal studies on eminence is especially informative in this respect.

In the following section, we will first discuss the important predictors of excellence as found in the literature on excellent professionals. Next, we will describe previous studies that have provided evidence for the differences between honors and non-honors students, leading to the central question of this study.

Predictors of excellence

The concept of ‘excellent professionals’ has not been clearly defined; studies in the field generally speak of persons with outstanding achievement, or eminence (Trost 2000), or, like Simonton (1999) does, of ‘people who made a name for themselves’, referring to their reputation. The theoretical perspective of excellence usually defines how researchers try to assess the construct. According to Simonton (1999), the most common assessment criteria are nominations by experts in the field; occupations of special positions, like political leaders; awards, such as Nobel prizes; and biographical entries in encyclopedias or similar sources. Criteria also depend on the domain. For scientific excellence for example, research productivity, citation ratings, and peer ratings, or combinations of these methods, are commonly used. One major focus of interest in studies of excellence in the last century has been on the conditions and characteristics related or contributing to excellence (Albert 1969; Friedman-Nimz and Skyba 2009). In a review of the research on characteristics that predict excellence in adult life, Trost concluded that a combination of characteristics is necessary for outstanding accomplishments in later life; however, no combination of predictors could explain more than 50% of the variance in adult achievement (Trost 2000: 332).

Several models have been designed in order to represent the combination of factors necessary for excellent performance in work, and one of the first and most renowned models was Renzulli’s (1986, 2003) ‘three ring conception of giftedness’. Renzulli’s model comprises a combination of three interacting basic clusters of human traits: ‘above average ability’, ‘creativity’ and ‘task commitment’, covering the traits of people with the potential to become creative and productive professionals (Renzulli 1986). Each of the model’s three components is necessary for creative performance, and no one component is sufficient in itself. Since 1986, a lot of research has been done in the field of giftedness and several variations, adjustments and alternatives to the three ring model have been created (for instance, Gagné 1995; Mönks and Katzko 2005; Sternberg 2003). Most models, like the Munich model of giftedness (Heller et al. 2005) and Gagné’s model (1995), are developmental models, and include the environmental factors that are necessary to allow potential talent to bloom. As we were particularly interested in the personal characteristics which are necessary to excel in work, we used Renzulli’s (1986, 2003) multidimensional conception of giftedness. Starting from Renzulli’s three rings, we chose to use only general intelligence instead of Renzulli’s ‘above average ability’, which also includes domain-specific abilities. General intelligence is likely to be involved as a central characteristic of giftedness (Detterman and Ruthsatz 1999; Sternberg 2005; Thompson et al. 2010). Further, ‘task commitment’ was replaced by the more commonly used concept of ‘motivation’, depicting task commitment as well as a love for learning. Renzulli (2003) also included ‘self-confidence’, and ‘the ability to identify significant problems within specialized areas’ under the heading of task commitment. We left these two out, because of their conceptual overlap with the concept of intelligence.

A brief review of the theory and empirical evidence for each of these three components as predictors of excellence in professional life follows, using a combination of retrospective and prospective longitudinal studies. Retrospective analysis of excellent professionals allows us to determine the adolescent antecedents of their achievements, such as their environment, developmental characteristics and traits. For this study, we were mainly interested in the traits that eminent people showed in their youth. Prospective longitudinal studies indicate whether traits, measured in youth predict their level of achievement in their professional life. According to Simonton (1994), the findings obtained using each method corroborate rather than contradict each other.

Intelligence

Regarding the concept of intelligence, there is broad consensus that cognitive abilities are organized hierarchically, with Spearman’s general intelligence topping over cognitive traits such as memory, and verbal and spatial abilities (Carroll 1993; McGrew 2009; Lubinski 2004; Schweizer et al. 2011). General intelligence is defined as ‘a very general mental capability that, amongst other things, involves the ability to reason, plan, solve problems, think abstractly, comprehend complex ideas, learn quickly and learn from experience’ (Baumert et al. 2009; Gottfredson 1997: 13).

Traditionally, social scientists have assumed that intelligence is the sole predictor of excellence in later life. Accordingly, the dominant operational definition of giftedness has long been based solely on measures of IQ (Callahan 2000; Tannenbaum 1996). Several longitudinal studies have proven that high intelligence is indeed a valid predictor of exceptional performance in professional life (Gottfredson 1997; Kuncel et al. 2004; Lubinski et al. 2006). In their longitudinal study of a group of students who had achieved exceptional SATs scores before the age of 13, Lubinski et al. (2006) found that the same students, only 10 years later, had obtained an impressive list of achievements, including numerous scientific publications, inventions, and original contributions to literature and the arts. Kuncel et al. (2004), in their meta-analysis, concluded that intelligence tests, specifically the Miller Analogies test, predict performance in graduate studies as well as job performance. In their recent review study, Kuncel et al. (2010) convincingly confirm earlier findings, finding strong correlations between intelligence and job performance, and conclude that ‘validities of cognitive ability tests are substantial and useful across industries, job families, and even cultures’ (p.333).

Creativity

Traits of creative persons are considered to be a result of interacting cognitive and attitudinal dimensions (Batey and Furnham 2006; Hennessey and Amabile 2010), including creative thinking, openness to experience, intelligence and motivation. Since the latter two are positioned in the two other (overlapping) Renzulli rings, we here focus on creative thinking and openness. The cognitive dimension (creative thinking) is defined in the Dictionary of the Psychological Association (Vandenbos 2007) as mental processes leading to a new invention, solution, or synthesis in any area. Openness to experience is one of five major domains, which are used to describe the human personality, namely an active imagination, aesthetic sensitivity, attentiveness to inner feelings, preference for variety and intellectual curiosity (Costa and McCrae 1992). Lists of the attitudinal characteristics of creative people are plentiful (Barron and Harrington 1981; Feist 1999; McCrea 1987; Selby et al. 2005; Simonton 1997; Treffinger et al. 2002). These lists overlap, and their contents make up openness to experience.

Creativity has been proven to be an important quality which enables people to develop into adults who are able to make a significant contribution to their domain (Renzulli 1986; Simonton 2000; Trost 2000). Creativity, measured during adolescence, is a valid predictor of excellent performance in adult life (Feist 1999; Milgram and Hong 1993; Simonton 1988; Tannenbaum 1983), and some researchers have found creativity to be an even better predictor of future achievements than intelligence. Milgram and Hong (1993), for example, studied a group of high school students over a period of 18 years, and found that creativity and creative performance were better predictors of achievements in adult life than intelligence or school grades. Park et al. (2008) found that intelligence itself predicts creativity. In a longitudinal study over the course of 25 years, the authors selected a large sample of students who were the top 1% of the SAT math test at the age of 13 and tracked their creative productiveness in their adult lives in terms of publications and patents earned. Their findings suggest that quantitative reasoning ability at an early age predicts scientific creativity and innovative accomplishment. These erratic findings regarding the relative importance of creativity and intelligence could be due to the (partial) overlap of the concepts of intelligence and creativity; one can consider divergence and fluidity of thinking as elements of intelligence as well as being the main components of creativity. Conversely, creativity also involves analytical and critical reasoning, as novel ideas must be reflected upon once they are produced. Despite the intertwined nature of intelligence and creativity, the literature on creativity indicates that creativity is more than simply intelligence.

Motivation

Motivation is a multifaceted concept (Pintrich 1999) and includes notions such as persistence, task commitment, intrinsic or extrinsic interest, the desire to learn and the drive to succeed (Friedman-Nimz and Skyba 2009). In our study, we narrowed the concept of motivation down to ‘a desire to learn’, ‘persistence’, and ‘the drive to excel’. The desire to learn is defined as the enjoyment of learning, characterized by an orientation towards mastery, curiosity, and the learning of challenging, difficult, and novel tasks (Gottfried et al. 2005). Adults with an academic interest actively search for cognitive stimulation and insights, seek out in-depth approaches to learning and find enjoyment in engaging in cognitive activities (Schick and Phillipson 2009; Biggs 1989). One may expect that the desire to learn and to master the material may lead people to put more time and effort into a task (Lens and Rand 2000). Accordingly, this aspect relates to another aspect of motivation: ‘persistence’, which has also been labeled as task commitment, diligence, determination, or perseverance regardless of setbacks and difficulties. The third motivational dimension, which we will call ‘the drive to excel’, refers to the desire to achieve good scores on external indicators of success, such as grades, as opposed to the mastery orientation, which resembles the ‘desire to learn’ dimension as described above (Dweck and Leggett 1988). This motivational factor has also been described as ‘external motivation’ and ‘performance motivation’. Harackiewicz et al. (2000) suggested that the optimal motivational pattern for college students includes goals based on both mastery (the desire to learn) and performance (the drive to excel).

Various studies have shown that all three factors are indispensible for intellectual and creative achievement. There is a consensus amongst researchers in the field that the ‘desire to learn’ is an important factor for academic achievement in one’s school, life and career (Collins and Amabile 1999; Gottfried et al. 2005; Schick and Phillipson 2009; Sternberg 2001). A wide of interest and curiosity are essential attributes for gifted individuals (Clark 2000; Goertzel et al. 2004; Tuttle and Becker 1983), and are considered to be independent predictors of giftedness (e.g. Gottfried et al. 2005).

From several studies on eminence, we can learn that following the desire to learn, motivational factors such as drive and persistence are predictors of eminence (Csikszentmihalyi 1993; Friedman-Nimz and Skyba 2009; Howe 1999; Renninger 2009; Simonton 1994; Treffinger et al. 2002; Trost 2000; Walberg et al. 2003). Empirical studies have shown that talented professionals must practice within their domain for several hours per day for a full decade before their latent capacity becomes actualized (Roe 1953; Ericsson 2006; Howe 1999; Walberg et al. 2003), showing that persistence is another predictor of excellent achievement. Roe (1953) examined the antecedents of 64 living eminent scientists in various fields using interviews and tests. Although there were marked differences between the groups from different disciplines, all of the scientists were driven by their absorption in their work. A landmark retrospective study on this topic was conducted by Cox (1926). She investigated the lives and achievements of 301 eminent people. Using primary sources such as publications, medals, citations, scores on intelligence tests as well as secondary materials such as biographies, she estimated their intelligence and personality traits, taking into account environmental factors. She concluded that high intelligence alone is insufficient for high achievement in adult life; those who became eminent all had certain personality traits in common, the most important of which were persistence, drive, and passion. The psychologist Howe (1999) traced the lives of eminent men, including for example Charles Darwin. Referring to childhood traits that contribute to creative productiveness, Howe concluded that motivational aspects like persistence, the capacity to concentrate and to resist distractions and intense curiosity are better predictors of eminence than measures of early intelligence. Walberg conducted several retrospective studies on eminent men and women (Walberg and Stariha 1992; Walberg et al. 1981), and found that the top ranking traits which eminent men and women showed during childhood, apart from high intelligence, were perseverance and diligence (Walberg et al. 2003).

The best-known longitudinal study on the school and work careers of gifted people was conducted by Louis Terman (1954). Terman kept track of the careers of over 1,500 highly intelligent children over the course of the lives, starting in 1921. Most of these promising children did not fulfill Terman’s expectations. In a follow up study, Terman and his colleagues tried to identify the non-intellectual factors that had influenced their levels of achievement. They concluded that the superiority of the successful people was especially marked in volitional traits, such as perseverance and the drive to excel (Terman 1954). In acknowledgment of these various findings, motivation has therefore been incorporated as a vital factor into many theories of giftedness (for instance, Dai et al. 1998; Gottfried et al. 2005; Lens and Rand 2000; Ziegler and Heller 2000; Renzulli 1986).

Summarizing, within Renzulli’s three rings, six characteristics are present, predicting excellence in professional life: intelligence, creative thinking, openness to experience, desire to learn, drive to excel, and persistence. In the next section, we review studies at university level regarding differences on these characteristics between honors and non-honors students.

Differences between honors and non-honors students

Considering the literature regarding excellence, we found that there was a reasonable amount of literature regarding the characteristics of gifted and talented students in primary and secondary school settings. Research on the characteristics of talented students at university level, however, is limited. Rinn and Plucker (2004) considered the literature on academically talented college students to be outdated, as little work has been published in the last two decades. Achterberg (2005), in her review of the literature about differences between honors and non-honors students in higher education, detected a ‘severe lack of descriptive evidence, comparisons, or empirical data based on respectable sample sizes’ (p. 5). A study that withstands this critique is that of Long and Lange (2002), who explored personality differences between honors and non-honors bachelor students in a large regional university in the United States. The student group was largely Caucasian, and covered a variety of disciplines, as well as liberal arts. In this study, honors students scored higher on the personality scales of conscientiousness and openness to experience, and were more likely to prepare for class, focused more on grades, and participated more in extra-curricular activities than their non-honors counterparts. However, according to the researchers, the magnitude of the differences were small.

Since 2005, a few studies have compared honors students and non-honors students in terms of specific traits. Comparing honors and non-honors students of the entire freshman population at Louisiana Tech University, a comprehensive public university, Kaczvinsky (2007) found that honors students were more academically confident, more intellectually interested, and more open to new ideas than their non-honors peers were. Rinn (2007) focused on the motivational differences between honors and gifted non-honors students, in a sample of 294 bachelor students in various disciplines in a large university in the Midwest of the United States. She found that honors students appeared to be more confident in their abilities. The scarcity of information on the differences between honors and non-honors students that has been gathered in the last two decades suggests that there is a need for additional studies. Moreover, the few existing studies on the differences between honors and non-honors students were conducted in the United States, and therefore could be regionally biased. Furthermore, none of these studies compared honors and non-honors students in terms of the combination of traits which have been found to be predictors of excellent achievement in professional life, which after all is a major objective of honors programs.

In this study, we compare honors and non-honors students on six characteristics that have been found to be central for creative productive professionals (intelligence, creative thinking, openness to experience, desire to learn, drive to excel, and persistence). Additionally, the development of a reliable questionnaire that measures these six characteristics was included as the first objective of this study.

Research questions:

-

1.

Can a questionnaire be developed for measuring the six characteristics which are found to be central for creative productive professionals that (a) is psychometrically sound, and (2) is brief and readily usable?

-

2.

Do honors students differ from non-honors students with respect to the combination of intelligence, creative thinking, openness to experience, desire to learn, drive to excel, and persistence?

-

3.

Which of these characteristics primarily differentiate between honors and non-honors students?

Methods

Participants

The participants in this study comprised 1,122 students, including 467 honors students and 655 non-honors students of Utrecht University, a large research university (30.344 students). In this university, about 21 honors programs and four honors colleges have been developed in the last 15 years, disciplinary as well as interdisciplinary. The participants were undergraduate students (41% 1st year students, 37% 2nd year students, and 22% 3rd year students) of seven different bachelor programs: Law, Humanities, Mathematics, Physics, Earth Sciences, Innovation & Environmental Sciences, and Liberal Arts and Sciences (LA&S). These programs had well-established honors programs with substantial student enrollment, except for the Humanities honors program, which was newly developed and started with 21 students. Despite of this, we included this program in order to keep the sample broad. Student samples of the programs included in the study were chosen by the program coordinators by selecting one or more classes in all three bachelor years to hand out the questionnaires. Student attendance in the selected classes and thus the response in the data gathering was nearly complete, as these classes were either very important or compulsory, both for honors and non-honors students.

Honors programs, in the Netherlands as well as elsewhere in the world, are diverse in the ways in which they are designed. In Utrecht University, there are several models for honors programs at undergraduate level, which are comparable to those in the United States. The 3-year Liberal Arts and Sciences Honors College is a full program, designed especially for honors students. Another common model is an enrichment program for a selected group of students, including specially designed honors courses, which are additions to the regular study program. The Humanities program belongs in this category. Most programs at Utrecht University combine the two models, meaning that honors students follow part of the regular program, engage in substitute components such as research projects, and follow an additional enrichment program. The Law and Earth Sciences and Innovation and Environmental Sciences courses in Utrecht University are examples of this model. Honors students are selected for these programs based on their prior achievements (school grades) and on their motivation, which is reflected implicitly in their self-selection or explicitly checked by their application letters and/or intake interviews.

Procedures

The students completed a paper and pencil questionnaire during class or in the break between classes. The questionnaires took approximately 20 min to complete, and were semi-anonymous: the students were asked to fill in their student number so that we were able to retrieve their gender, age and year of study from the administrative system. Their names remained unknown to the researchers. Two subjects were removed from the analysis as they were missing more than 5% of their data. Eleven students were of non-traditional age (older than 27) and were also removed from the study, leaving 1,109 cases from the original 1,122.

Materials

In the absence of an adequate existing questionnaire for university level that measures all of the components of Renzulli’s (1986) model, we developed a self-report questionnaire using parts of existing validated instruments. These instruments included: Goldberg’s (1999) ‘intellect’ scale from the International Personality Item Pool (IPIP-NEO) for ‘intelligence’ and the Scale of Creative Attributes and Behavior (SCAB) instrument (Kelly 2004) for ‘creative thinking’. The scale measuring openness to experience was founded on a Dutch version of the Big Five Openness to Experience scale (Gerris et al. 1998), and for the ‘desire to learn’ scale, the International Personality Item Pool Values In Action (Peterson and Seligman 2004) was used as a basis. The items of the ‘persistence’ scale were derived from the Perseverance IPIP-VIA scale (Peterson and Seligman 2004), and the ‘drive to excel’ was measured using three items adapted from the work of Elliot and McGregor (2001). Based on an exploratory study, a questionnaire was developed, which consisted of 63 items. In order to ensure that the format of the items was similar across the whole questionnaire, the scales of the items were adjusted to fit a seven-point Likert type scale, ranging from ‘not at all true of me’ (1) to ‘very true of me’ (7).

Both English and Dutch versions of the questionnaire were administered. A back translation procedure (Brislin 1986) involving four English-Dutch bilingual university instructors was applied to ensure cross-cultural conceptual equivalence. The back translations were compared until consistent meanings were obtained.

Analysis

Multivariate analysis of variance was conducted, using General Linear Models (GLM) with SPSS 16, to find out whether the (combination of) the six talent factors differ between honors and non-honors students, which was the central question of this study. The independent variables were honors (yes or no), and study program. Gender and year of study were entered as covariates. The dependent variables were the six scales; the ‘talent factors’ described above. The order of entry of the independent variables was study program, then honors, as our main interest was in the differences between honors and non-honors students. Any missing values (< 2%) were replaced using the two-way imputation method described in van Ginkel and van der Ark (2008). The results of the evaluation of normality, linearity and multicollinearity were satisfactory. As a preliminary test for robustness, Tabachnick and Fidell (2007) suggest comparing sample variances for each dependant variable across the groups. The ratio of the largest to the smallest group variance did not approach 10:1 for any dependent variable. As a matter of fact, the largest to the smallest group ratio was about 1.9:1. The sample sizes were widely discrepant, with a ratio of 4.3:1. However, with very small differences in variance, this discrepancy in sample sizes does not invalidate the use of multivariate analysis (Tabachnick and Fidell 2007).

In order to answer the second research question, concerning the importance of each of the six talent factors’ unique contribution to the differences between the groups (honors and non-honors), discriminant analysis was conducted. The six variables were not independent and show significant correlations that vary between 0.17 and 0.53. Intelligence, creativity and the desire to learn have the highest correlations (between 0.41 and 0.53). As these variables are correlated, the univariate tests do not properly show the relative importance of the variables in distinguishing honors students from non-honors students. In order to be able to interpret the contribution of each of the variables to the differences between the two groups and to determine which of the variables discriminate most, direct discriminant analysis was used with the six talent scales.

In this study we used a significance level of 5%.

Results

The first section reports of the scale descriptives. In the second section, we report whether the two groups (honors and non-honors) differed from one another in terms of the six talent factors. In the third section, we examine which of the six talent factors accounted for the largest differences between the honors and non-honors groups.

Scale descriptives

The original questionnaire consisted of 63 items, divided over 6 scales: intelligence, creative thinking, openness to experience, desire to learn, drive to excel, and persistence. Based on reliability and factor analyses, items were deleted, reformulated, or replaced. The resulting questionnaire consisted of 31 items (see “Appendix”).

The corrected scales were separately factor-analyzed, and in all six scales, the items loaded on a single factor, showing unidimensionality of the scales (Field 2009). Using the often used rule of thumb of 0.7 as an acceptable alpha value, and given the unidimensionality of the scales (Cortina 1993; George and Mallery 2003; Nunnaly 1978), all scales are acceptable, despite the small number of items in some of the scales.

Table 1 presents a sample item and the reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) for each of the six scales.

In order to examine whether or not the items were distributed correctly over the six scales, a principal component analysis was conducted on the 31 items with oblique rotation (Oblimin). The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure verified the adequacy of the sample for analysis (KMO = 0.87). Seven components had eigenvalues over Kaiser’s criterion of one, and collectively explained 54% of the variance. The pattern matrix showed seven factors, which were almost identical to the six original scales, except for the persistence scale. The persistence items loaded into two subscales: one focused on hard work and determination, and the other focused on perseverance regardless of setbacks. For conceptual reasons, these two factors of persistence were kept in one scale. With a cutoff of 0.40 for the inclusion of a variable in the interpretation of a factor, 24 of 31 items loaded only on their original factor; one item did not reach the 0.40 cutoff, another item, ‘preference for complexity’, loaded higher on the creativity scale than on its original scale of intelligence. Theoretically, however, this is not surprising, as preference for complexity, when understood as tolerance of ambiguity, is related to creativity (Zenasni et al. 2008). Five items loaded into two scales, which was to be expected considering the overlapping of the three rings in Renzulli’s model. The overlap was found mainly between the Creativity and Desire to learn scales. In order to keep the reliability sufficiently high for all of the scales, all items were kept in their original scales. Intelligence and Drive to excel correlated 0.30, which was modest and limited to one pair of factors; remaining correlations were low.

Differences between honors and non-honors students

The second research question focused on determining the differences between honors and non-honors students with respect to the six talent factors (intelligence, creative thinking, openness to experience, the drive to excel, the desire to learn, and persistence). Table 2 shows the means and standard deviations.

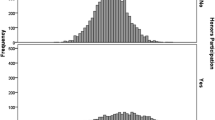

Mean scores for all students show highest scores for their Desire to learn (5.2 for non-honors and 5.8 for honors groups), while the scores for Drive to excel are lowest (4.1 for non-honors and 4.8 for honors groups). These two characteristics also show the largest difference between honors and non-honors groups. The scores on Drive to excel show the largest standard deviations, especially for the non-honors group. Further, it is noticeable that honors students in the physics department assess themselves lower on Creative thinking, Drive to excel, and Persistence than their non-honors peers do.

GLM analysis using Wilks’ criterion, showed that the combined dependent variables were significantly affected by the distinction in honors and non-honors groups (p = .000; partial η² = .04), the study program (p = .000; partial η² = .04), and gender (p = .000; partial η² = .05), but not by year of study. Univariate between-subjects tests showed significant differences between honors and non-honors students when adjusted for study program, gender and year of study, for five of the six variables; ‘persistence’ being the variable that did not show a significant difference.

As our findings showed that the study program is a significant variable, we examined how the differences between honors and non-honors students varied across study programs. We conducted separate GLM analysis for four study programs: Law (91 honors and 261 non-honors students), Humanities (21 honors and 121 non-honors students), Physics (40 honors and 59 non-honors students), and LA&S (301 students). The non-honors students of the whole data set (N = 469) were used as a control group for the LA&S honors group. The other three study programs were not included in the analysis, due to a lack of sufficient data for the honors groups. In these additional analyses, only gender was included as a covariate.

The results of the separate multivariate and univariate analyses for the four study programs are presented in Table 3. For all of the study programs, the multivariate analysis showed significant differences between honors and non-honors students, with effect sizes (partial η²) between 0.15 and 0.25. The results of the univariate analysis between subjects showed different results for the four study programs. For the Law students, univariate between-subjects tests revealed statistically significant differences between honors and non-honors students for all six variables, with the largest effect sizes for the desire to learn (partial η² = 0.15) and intelligence (partial η² = 0.10). For Humanities students, univariate between-subjects tests demonstrated that the differences between honors and non-honors students were statistically significant for openness to experience (partial η² = 0.08) and the desire to learn (partial η² = 0.09). Univariate between-subjects tests for the six variables did not show significant differences in the Science groups, and finally, univariate tests for the LA&S students showed a significant effect for all six variables, with the largest effect sizes for creative thinking (partial η² = 0.15) and the drive to excel (partial η² = 0.11).

Main contributors to the differences between honors and non-honors students

In order to be able to interpret the contribution of each of the variables to the differences between the two groups, direct discriminant analysis was used with the six talent scales as predictors of membership of the honors or non-honors group, corrected for gender. This was executed for the whole data set, as well as separately for the four study programs. The discriminant function that was calculated revealed a significant overall difference between the honors and non-honors students (p = 0.00, Wilk’s = 0.83, χ²(7) = 159, canonical R² = 0.17). This means that 17% of the variance can be accounted for by the combined predictors. The standardized discriminant function coefficient predictors and the discriminant function, as shown in Table 5, suggest that the best predictors for distinguishing honors students from non-honors students were the desire to learn, the drive to excel and creativity.

As shown in Table 4, separate discriminant function analyses for the four separate study programs revealed significant differences between the honors and non-honors groups.

The standardized discriminant function coefficients of predictors, as shown in Table 5, show that the best predictors for distinguishing honors students from non-honors students differ for the various study programs. The main predictor for Law honors students is their drive to excel (0.60). For Humanities students, their drive to excel (0.56) and their openness to experience (0.55) contribute most to the differences between honors and non-honors students. For Physics students, their desire to learn (1.00) and creative thinking (-1.01) show the greatest difference between honors and non-honors students. The main predictor for the LA&S honors students was creative thinking (0.62).

Conclusions and discussion

The central question of this study was whether honors students differ from non-honors students with respect to the talent factors (intelligence, creative thinking, openness to experience, persistence, the desire to learn and the drive to excel) that have been found to be essential for exceptional accomplishment in professional life. The results showed that honors students are significantly different from non-honors students in terms of the combined as well as the separate variables, with the exception of persistence. The effect sizes were medium when measured within the separate disciplines, but small for the group as a whole. Two issues need to be taken into account here. First, honors and regular programs do not unambiguously distinguish talented students from regular students in their selection processes. As Rinn and Plucker (2004) state, groups of non-honors students will also include a proportion of potential honors students. Such potential honors students could have various reasons for not applying to an honors program. They might not want to belong to an ‘elite’ group or might not want to spend extra time on a study program. In addition, these students may simply not be aware of the existence of honors programs, which is plausible given that some of these programs are relatively new. A second issue to take into account is that effect size in the combined analysis has been affected by the different trends we found across study programs.

The second research question concerned which of the talent characteristics contribute most powerfully to the differentiation between honors and non-honors groups. The strongest distinguishing factors for honors and non-honors students appeared to be the desire to learn, the drive to excel and creative thinking, while intelligence and persistence did not differentiate groups very much. The strong distinguishing value of creative thinking was unexpected, as creativity is not an explicit selection criterion for most honors programs. Intelligence was the weakest factor. This was surprising, as honors students are selected on their average school grades, and grades are affected by intelligence (Lubinski 2004). An explanation for the negligible distinguishing value of intelligence could be found in the fact that average students are more likely to overestimate their ability than gifted students, whereas gifted students tend to base their judgment of their ability to succeed more accurately on the actual difficulty level (Dai et al. 1998; Pajares 1996). Persistence was assumed to be necessary for high achievement in secondary education, which is in turn a selection criterion for many programs. Chamorro-Premuzic and Arteche (2008) suggested that persistence and intelligence compensate for each other in terms of achievement, which could explain the low distinguishing value we found for persistence. This would imply that these honors students were intelligent enough to achieve well in school without having to put much energy into their work. The other two motivational factors however, did differentiate between honors and non-honors students. In comparison with the non-honors group, these honors students of Utrecht University had a greater desire to learn, which concurs with Kaczvinsky’s (2007) findings in a similar study in the US. The drive to excel is not very dominant in the Dutch educational culture, where students are not as much grade-oriented as students in for example the United States are. It is therefore not surprising that the mean scores for ‘drive to excel’ are lower than the scores on any of the other factors. The drive to excel however was one of the important traits differentiating honors from non-honors students, indicating that honors students aim to get the most out of their education: in learning profits as well as the recognition of it.

As we found substantial differences between honors and non-honors students across disciplines, we further explored these differences within four of the study programs. In all programs, honors groups differed significantly on the combined talent factors from their non-honors peers. The profiles of these differences, however, varied according to the study program. While Law and Humanities honors students differed from their non-honors peers in terms of their drive to excel, Physics honors students were primarily more eager to learn than their non-honors peers were, while the LA&S honors group distinguished themselves predominantly in terms of creative thinking. The variation in results between the study programs could be explained firstly by the differences in selection procedures used in the various programs. In the Law and LA&S programs, a combination of grades, application letters and interviews are used, while in the Physics and Humanities departments, selection procedures predominantly rely on self–selection. The differences between honors and non-honors students in both the Law and LA&S groups were relatively strong, with significant differences in each of the six talent factors. In the two programs with less comprehensive selection methods, the differences between honors and non-honors students were less convincing, with Humanities students showing significant differences for only two of the talent factors, and Physics honors students not scoring significantly higher for any of the factors. It may well be that comprehensive selection procedures account for more distinctive differences between honors and non-honors students. A second explanation for the differences we found between study programs could be found in the diversity of the academic cultures of disciplines (Becher and Trowler 2001). Differences in academic cultures imply different habits, values, and rules, serving as a background reference point for students’ assessment of their characteristics. In a competitive culture for example, students might assess their own drive to excel lower than in a culture with an egalitarian tradition.

The unusual scores of the Physics honors group necessitate further reflection. Physics honors students did not assess themselves to be significantly more intelligent than their non-honors peers, and their score for ‘persistence’ was noticeably lower. These low scores for persistence are surprising, as in their honors program, Physics students combine two bachelor programs (physics and mathematics) which can be assumed to be quite demanding. It is possible that these students are not accustomed to working hard, because there was no need for them to do so at school as they were intelligent enough to succeed with little effort (Chamorro-Premuzic and Arteche 2008). The insignificant differences in intelligence scores between Physics honors and non-honors students were also unexpected, while honors students had significantly higher average school grades (8.1 for honors and 7.6 for non-honors). A clarification might be found using the ‘big fish little pond’ effect, which will be explained below.

Limitations

Although this study provides important insights in the differences between honors and non-honors students across their study programs, there are several limitations of this study that need to be mentioned. First, this study used a sample of students at one university, and so the results cannot be generalized unproblematically. Second, the data presented in this study are all self-reported. Although this is a logical and defensible methodology in its own right, self-report questionnaires could threaten the validity of this study. One threat is the general tendency for individuals to respond in socially desirable ways. The anonymity of the survey, which allowed respondents to respond truthfully, was intended to mitigate this threat. Further, the influence of the reference group could influence students’ self-assessment. Although the questionnaire focused on measuring personal dispositions, their peer group may well influence students’ assessments. This effect, referred to by Marsh (1987) as the ‘big fish little pond effect’, concerns the selected group of highly capable peers that students are part of once they enroll in an honors program. According to Marsh, students tend to assess their own competence in comparison with their peer group, which, for honors students, is a selective group of highly able students. We tried to reduce the influence of this effect by avoiding items that directed students to compare themselves to their peers and by focusing our attention on relatively stable dispositions. Nonetheless, there are indications that the students used their peer group as a point of reference. The Physics honors group, for example, assessed their intelligence lower than the Law honors group did (5.2 and 5.4), whereas the Physics students’ average school grades were a great deal higher (8.1 and 7.5). Assuming that the honors groups assessed their qualities as such because of their highly able reference groups, the differences between honors and non-honors students per program may have been underestimated in this study.

Implications

As the honors students in this study differed significantly from non-honors students in terms of the characteristics which predict excellent professional achievement, it seems justifiable to provide special attention for the education of these students. After all, the effectiveness of education depends to a large extent on the fit between the learning environment and the abilities, interests and motivation of the students (McKeachie 1986; Snow 1986; Pascarella and Terenzini 1991). These students need to be challenged appropriately and they require a learning environment that matches their abilities, interests and level of motivation. Honors students, however, are not a homogeneous group; the differences we found between these programs emphasize the value of insights in the characteristics of honors students. These differences across disciplines provide grounds for program leaders to reflect on their selection methods. The programs with the most extensive selection procedures showed the strongest differences between honors and non-honors groups. Self-selection seems to attract honors students with a strong drive to excel, while the desire to learn and persistence are presumably more important motivational factors for excellent achievement in professional life (Ericsson 2006; Howe 1999).

Furthermore, the differences between the student groups across disciplines indicated that the appropriate learning environments and teaching methods could differ between the various programs, providing reasons for the importance of matching the programs to the characteristics of the students in the honors groups.

The findings of this study provide three directions for further research. One direction would be the selection of honors students. The results of this study indicate that a more comprehensive method for the selection of honors students could provide a sharper distinction between honors and non-honors groups. In future research, it is worthwhile to focus on the selection processes and the effectiveness of the various elements of the methods of selection. A second area of interest is the relationship between the (interacting) talent characteristics and success in professional domains. The results of the present study suggest that honors groups do have the characteristics needed for excellent performance in professional life, but we do not know whether they have these traits in sufficient measure and in successful combinations. Furthermore, as we found different talent profiles across disciplines, it could be valuable to relate the relative importance of these characteristics to academic domains. A third field of interest is the interaction between the talented students and their learning environment. This study focused on the characteristics students require for excellence in their professional lives, leaving out the crucial role of their environment in developing students’ talents. A developmental perspective is needed to provide insights into how to teach honors students effectively. A better understanding of the interaction between students’ motivational, creative and intellectual aptitudes on the one hand, and the learning environment and teaching methods on the other hand, could lead to better learning in honors groups.

References

Achterberg, C. (2005). What is an honors student? Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council, 6(1), 75–81.

Albert, A. S. (1969). Genius: Present-day status of the concept and its implications for the study of creativity and giftedness. American Psychologist, 24(8), 743–753.

Barron, F., & Harrington, D. M. (1981). Creativity, intelligence and personality. Annual Review of Psychology, 32, 439–476.

Batey, M., & Furnham, A. (2006). Creativity, intelligence, and personality: A critical review of the scattered literature. Genetic, Social & General Psychology Monographs, 132(4), 355–429.

Baumert, J., Lüdtke, O., Trautwein, U., & Brunner, M. (2009). Large-scale student assessment studies measure the results of processes of knowledge acquisition: Evidence in support of the distinction between intelligence and student achievement. Educational Research Review, 4, 165–176.

Becher, T., & Trowler, P. R. (2001). Academic Tribes and Territories; Intellectual enquiry and the culture of disciplines (2nd ed.). Buckingham: Open University Press.

Biggs, J. B. (1989). Approaches to the enhancement of tertiary teaching. Higher Education Research and Development, 8, 7–25.

Brislin, R. W. (1986). A culture general assimilator: Preparation for various types of sojourns. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 10, 215–234.

Callahan, C. M. (2000). Intelligence and Giftedness. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of intelligence (pp. 159–175). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Carroll, J. B. (1993) Human cognitive abilities: A survey of factor-analytical studies. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Arteche, A. (2008). Intellectual competence and academic performance: Preliminary validation of a model. Intelligence, 36, 564–573.

Clark, L. (2000). A review of the research on personality characteristics of academically talented college students. In L. Clark & C. Fuiks (Eds.), Teaching and learning in honors (pp. 7–20). Radford, VA: The National Collegiate Honors Council.

Cohen, P. A. (1984). College grades and adult achievement: A research synthesis. Research in Higher Education, 20(3), 281–293.

Collins, M. A., & Amabile, T. M. (1999). Motivation and creativity. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 297–312). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cortina, J. M. (1993). What is coefficient Alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 98–104.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). NEO personality Inventory professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Cox, C. M. (1926). Genetic studies of genius; the early mental traits of three hundred geniuses. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. C. (1993). Genius & Eminence (2nd ed.). Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Dai, D. Y., Moon, S. M., & Feldhusen, J. F. (1998). Achievement motivation and gifted students: A social cognitive perspective. Educational Psychologist, 33, 45–63.

Detterman, D. K., & Ruthsatz, J. (1999). Toward a more comprehensive theory of exceptional abilities. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 22(2), 148–158.

Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95, 256–273.

Elliot, A., & McGregor, H. (2001). A 2 × 2 achievement goal framework. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 501–519.

Ericsson, K. A. (2006). The influence of experience and deliberate practice on the development of superior expert practice. In K. A. Ericsson, N. Charness, P. J. Feltovich, & R. R. Hoffman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of expertise and expert performance (pp. 683–703). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Feist, G. J. (1999). A meta-analysis of personality in scientific and artistic creativity. Personality & Social Psychology Review, 2(4), 290–309.

Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Friedman-Nimz, R., & Skyba, O. (2009). Personality qualities that help or hinder gifted and talented individuals. In L. V. Shavinina (Ed.), International handbook on giftedness (pp. 421–435). The Netherlands, Quebec, Canada: Springer Science and Business Media B. V.

Gagné, F. (1995). From giftedness to talent: A developmental model and its impact on the language of the field. Roeper Review, 18(2), 103–111.

George, D., & Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference. 11.0 update (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Gerris, J. R. M., Houtmans, M. J. M., Kwaaitaal-Roosen, E. M. G., de Schipper, J. C., Vemulst, A. A., & Janssens, J. M. A. M. (1998). Parents, adolescents, and young adults in Dutch families: A longitudinal study. Nijmegen: Institute of Family Studies, University of Nijmegen.

Goertzel, V., Goertzel, M., Goertzel, T., & Hansen, A. (2004). Cradles of eminence: Childhoods of more than 700 famous men and women (2nd ed.). Scottsdale: Great Potential Press.

Goldberg, L. R. (1999). A broad-bandwidth, public-domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of several five-factor models. In I. Mervielde, I. Deary, F. DeFruyt, & F. Ostendorf (Eds.), Personality psychology in Europe (Vol. 7, pp. 7–28). The Netherlands: Tilburg University Press.

Gottfredson, L. S. (1997). Why g matters: The complexity of everyday life. Intelligence, 24(1), 79–132.

Gottfried, A. W., Eskeles Gottfried, A., Cook, C. R., & Morris, Ph. E. (2005). Educational characteristics of adolescents with gifted academic intrinsic motivation: A longitudinal investigation from school entry through early adulthood. Gifted Child Quarterly, 49(2), 172–186.

Harackiewicz, J. M., Barron, K. E., Tauer, J. M., Carter, S. M., & Elliot, A. J. (2000). Short-term and long-term consequences of achievement goals: Predicting interest and performance over time. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(2), 216–230.

Heller, K. A., Perleth, C., & Lim, T. K. (2005). The Munich model of giftedness designed to identify and promote gifted students. In R. J. Sternberg & J. W. Davidson (Eds.), Conceptions of giftedness (pp. 147–170). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hennessey, B. A., & Amabile, T. M. (2010). Creativity. The Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 569–598.

Howe, M. J. A. (1999). Genius explained. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hoyt, D. P. (1966). College grades and adult accomplishment: A review of research. The Educational Record, 47, 70–75.

Kaczvinsky, D. P. (2007). What is an honors student? A Noel-Levitz survey. Journal of the National Collegiate Honors Council, 8(2), 87–95.

Kelly, K. E. (2004). A brief measure of creativity among college students. College Student Journal, 38, 594–596.

Kuncel, N. R., Hezlett, S. A., & Ones, D. S. (2004). Academic performance, career potential, creativity, and job performance: Can one construct predict them All? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(1), 148–161.

Kuncel, N. R., Ones, D. S., & Sackett, P. R. (2010). Individual differences as predictors of work, educational, and broad life outcomes. Personality and Individual Differences, 49, 331–336.

Lens, W., & Rand, P. (2000). Motivation and cognition: Their role in the development of giftedness. In K. A. M. Heller, J. Franz, R. J. Sternberg, & R. F. Subotnik (Eds.), International handbook of giftedness and talent (pp. 193–202). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Long, E. C. J., & Lange, S. (2002). An exploratory study: A comparison of honors and nonhonors students. The National Honors Report, 23(1), 20–30.

Lubinski, D. (2004). Introduction to the special section on cognitive abilities: 100 years after spearman’s (1904) “‘General intelligence’, objectively determined and measured’’. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(1), 96–111.

Lubinski, D., Benbow, C. P., Webb, R. M., & Bleske-Reschek, A. (2006). Tracking exceptional human capital over two decades. Psychological Science, 17(3), 193–199.

Marsh, H. W. (1987). The big-fish-little-pond effect on academic self-concept. Journal of Educational Psychology, 79(3), 148–161.

McCrea, R. R. (1987). Creativity, divergent thinking, and openness to experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(6), 1258–1265.

McGrew, K. S. (2009). CHC theory and the human cognitive abilities project: Standing on the shoulders of the giants of psychometric intelligence research. Intelligence, 37, 1–10.

McKeachie, W. J. (1986). Teaching Tips (8th ed.). Lexington, Mass: Heath.

Milgram, R. M., & Hong, E. (1993). Creative thinking and creative performance in adolescents as predictors of creative attainments. Roeper Review, 15(3), 135.

Mönks, F. J., & Katzko, M. W. (2005). Giftedness and Gifted Education. In R. J. Sternberg & J. W. Davidson (Eds.), Conceptions of giftedness (pp. 187–200). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Nunnaly, J. (1978). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Pajares, F. (1996). Self-efficacy beliefs in achievement settings. Review of Educational Research, 66, 543–578.

Park, G., Lubinski, D., & Benbow, C. P. (2008). Ability differences among people who have commensurate degrees matter for scientific creativity. Psychological Science, 19(10), 962–975.

Pascarella, E., & Terenzini, P. (1991). How college affects students: Findings and insights from twenty years of research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. New York: Oxford University Press/Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Pintrich, P. (1999). The role of motivation in promoting sustained self-regulated learning. International Journal of Educational Research, 31(6), 459–470.

Renninger, K. A. (2009). Interest and identity development in instruction: An inductive model. Educational Psychologist, 44(2), 105–118.

Renzulli, J. S. (1986). The three-ring conception of giftedness. In R. J. Sternberg & J. E. Davidson (Eds.), Conceptions of giftedness (pp. 53–92). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Renzulli, J. S. (2003). The three-ring conception of giftedness: Its implications for understanding the nature of innovation. In L. V. Shavinina (Ed.), The international handbook on innovation (pp. 79–95). Oxford: Elsevier.

Rinn, A. N. (2007). Effects of programmatic selectivity on the academic achievement, academic self-concepts, and aspirations of gifted college students. Gifted Child Quarterly, 51(3), 232–245.

Rinn, A. N., & Plucker, J. A. (2004). We recruit them, but then what? The educational and psychological experiences of academically talented undergraduates. Gifted Child Quarterly, 48(1), 54–67.

Roe, A. (1953). The making of a scientist. New York: Dodd, Mead.

Schick, H., & Phillipson, S. N. (2009). Learning motivation and performance excellence in adolescents with high intellectual potential: What really matters? High Ability Studies, 20(1), 15–37.

Schweizer, K., Troche, S. J., & Rammsayer, T. H. (2011). On the special relationship between fluid and general intelligence: New evidence obtained by considering the position effect. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 1249–1254.

Selby, E. C., Shaw, E. J., & Houtz, J. C. (2005). The creative personality. Gifted Child Quarterly, 49(4), 300–314.

Simonton, D. K. (1988). Scientific genius: A psychology of science. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Simonton, D. K. (1994). Greatness, who makes history and why? New York: The Guilford Press.

Simonton, D. K. (1997). Creative productivity: A predictive and explanatory model of career trajectories and landmarks. Psychological Review, 104(1), 66–89.

Simonton, D. K. (1999). Significant samples: The psychological study of eminent individuals. Psychological Methods, 4(4), 425–451.

Simonton, D. K. (2000). Creativity: Cognitive, personal, developmental, and social aspects. American Psychologist, 55(1), 151–158.

Snow, R. E. (1986). Individual differences and the design of educational programs. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1029–1039.

Sternberg, R. J. (2001). Giftedness as developing expertise: A theory of the interface between high abilities and achieved excellence. High Ability Studies, 12(2), 159–179.

Sternberg, R. J. (2003). WICS as a model of giftedness. High Ability Studies, 14(2), 109–137.

Sternberg, R. J. (2005). The WICS model of giftedness. In R. J. Sternberg & J. E. Davidson (Eds.), Conceptions of giftedness (2nd ed., pp. 327–342). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Tannenbaum, A. J. (1983). Gifted children: Psychological and educational perspectives. New York: Macmillan.

Tannenbaum, A. J. (1996). The IQ controversy and the gifted. In C. P. Benbow & D. Lubinski (Eds.), Intellectual talent (pp. 44–77). Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press.

Taylor, C. W., Albo, D., Holland, J., & Brandt, G. (1985). Attributes of excellence in various professions: Their relevance to the selection of gifted/talented persons. Gifted Child Quarterly, 29(1), 29–34.

Terman, L. M. (1954). The discovery and encouragement of exceptional talent. American Psychologist, 9(6), 221–230.

Thompson, L. A., & Oehlert, J. (2010). The etiology of giftedness. Learning and individual Differences, 20, 298–307.

Treffinger, D. J., Young, G. C., Selby, E. C., & Stephardson, C. (2002). Assessing creativity: A guide for educators. [Research monograph series]. Washington DC: National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented, Storrs, CT.

Trost, G. (2000). Prediction of excellence in school, university and work. In K. A. Heller, F. J. Mönks, R. J. Sternberg, & R. F. Subotnik (Eds.), International handbook of giftedness and talent (2nd ed., pp. 317–327). Oxford: Elsevier.

Tuttle, F. B., & Becker, L. A. (1983). Characteristics and identification of gifted and talented students (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: National Education Association.

VandenBos, G. R. (Ed.). (2007). APA Dictionary of psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

van Ginkel, J. R., & van der Ark, L. A. (2008). SPSS Syntax for two way imputation of missing test data. Tilburg, The Netherlands: Tilburg University.

Walberg, H. J., & Stariha, W. E. (1992). Productive human capital: Learning, creativity and eminence. Creativity Research Journal, 5(4), 323–340.

Walberg, H. J., Shiow-Ling Tsai, S.-L., Weinstein, T., Gabriel, C. L., Pinzur Rasher, S., Rosecrans, T., et al. (1981). Childhood traits and environmental conditions of highly eminent adults. Gifted Child Quarterly, 25(2), 103–107.

Walberg, H., Williams, D. B., & Zeiser, S. (2003). Talent, accomplishment, and eminence. In N. E. Colangelo & G. A. Davis (Eds.), Handbook of gifted education (3rd ed., pp. 350–357). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Zenasni, F., Besançon, M., & Lubart, T. (2008). Creativity and tolerance of ambiguity: An empirical study. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 42(1), 61–73.

Ziegler, A., & Heller, K. A. (2000). Conceptions of giftedness from a meta-theoretical perspective. In K. A. Heller, F. J. Mönks, R. J. Sternberg, & R. F. Subotnik (Eds.), International handbook of giftedness and talent (2nd ed., pp. 3–21). Oxford: Elsevier.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Scager, K., Akkerman, S.F., Keesen, F. et al. Do honors students have more potential for excellence in their professional lives?. High Educ 64, 19–39 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-011-9478-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-011-9478-z