Abstract

Microsatellite genotyping is a common DNA characterization technique in population, ecological and evolutionary genetics research. Since different alleles are sized relative to internal size-standards, different laboratories must calibrate and standardize allelic designations when exchanging data. This interchange of microsatellite data can often prove problematic. Here, 16 microsatellite loci were calibrated and standardized for the Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar, across 12 laboratories. Although inconsistencies were observed, particularly due to differences between migration of DNA fragments and actual allelic size (‘size shifts’), inter-laboratory calibration was successful. Standardization also allowed an assessment of the degree and partitioning of genotyping error. Notably, the global allelic error rate was reduced from 0.05 ± 0.01 prior to calibration to 0.01 ± 0.002 post-calibration. Most errors were found to occur during analysis (i.e. when size-calling alleles; the mean proportion of all errors that were analytical errors across loci was 0.58 after calibration). No evidence was found of an association between the degree of error and allelic size range of a locus, number of alleles, nor repeat type, nor was there evidence that genotyping errors were more prevalent when a laboratory analyzed samples outside of the usual geographic area they encounter. The microsatellite calibration between laboratories presented here will be especially important for genetic assignment of marine-caught Atlantic salmon, enabling analysis of marine mortality, a major factor in the observed declines of this highly valued species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the past three to four decades the application of genetic techniques has revolutionized research in the fields of ecology, evolution, conservation and wildlife management, and the advent of ‘next-generation’ biotechnologies continues to do so (Hudson 2008). Currently, microsatellites are amongst the most popular markers in molecular ecology and may remain so for the next 5–10 years (Moran et al. 2006): they are easily amplified by PCR, highly polymorphic, follow a simple mode of Mendelian inheritance and many sophisticated computer programs exist, allowing thorough analysis of large datasets (Excoffier and Heckel 2006). Expertise in their use is widespread and they are likely to find continued use in paternity analysis (e.g. Glaubitz et al. 2003), genetic stock identification and assignment testing (Narum et al. 2008), as well as in conservation and population genetics, assessment of dispersal and invasive species biology.

One advantage of microsatellites for the present is the existence of large historical datasets. This is especially relevant for modern conservation applications which often require a broad geographic scope varying from studies on a local scale involving one or a few research groups, to projects aimed at conserving a species across its entire range, which are frequently collaborative in nature (e.g. Moran et al. 2006). Such collaborative research programmes are likely to continue to make use of microsatellite based approaches due to the possibility of combining pre-existing datasets across different research groups, as well as expanding them with the latest technological and methodological advances (e.g. large-scale single nucleotide polymorphism discovery and genotyping) to address significant research challenges in a practical context.

A consequence of collaboration is the necessary interchange of genetic data between laboratories. However, the exchange of microsatellite data is often regarded as problematic as it poses several challenges (reviewed in Moran et al. 2006), including the fact that, due to historical influences/factors, different laboratories frequently use different sets of microsatellite markers and that allelic designations are not consistent between laboratories. Standardization of allelic designations can be particularly problematic since the size of a fragment determined by electrophoresis does not necessarily correspond to its actual length determined by direct sequencing (Haberl and Tautz 1999; Pasqualotto et al. 2007). The use of different sequencing machines with associated differences in chemistry can also result in differing allelic designations for the same allele between laboratories (e.g. Delmotte et al. 2001; Moran et al. 2006), as can differences in the fluorophore used to label a particular primer, whether the forward or reverse primer is labelled, etc.

Standardization and calibration are of much value, however, and recent examples include projects to facilitate exchange of genetic information in a horticultural context (identification of grapevine cultivars (This et al. 2004), olives (Doveri et al. 2008) and apple cultivars (Baric et al. 2008)) and validation of microsatellite scores between laboratories working on the fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus (Pasqualotto et al. 2007). In a fisheries context, projects include the coast-wide management of Pacific salmon species such as Oncorhynchus mykiss (Stephenson et al. 2009) and Oncorhynchus tshawytscha (Seeb et al. 2007).

One aspect of inter-laboratory comparisons sometimes ignored is the possibility to assess the extent and partitioning of genotyping error based on consensus genotypes identified across laboratories. Assessment of genotyping error is important in population genetics, but historically it has been largely ignored outside of forensic studies (Bonin et al. 2004; Pompanon et al. 2005). Errors can arise during PCR and electrophoresis, or during analysis and data handling. ‘Null alleles’ occur when a mutation arises in the flanking sequence where design characteristics of PCR primers can lead to amplification failure of a particular allele (Callen et al. 1993), although their occurrence is not necessarily a problem for inter-laboratory comparisons unless primers are redesigned by different laboratories. ‘Allelic dropout’ occurs due to random preferential amplification of one allele during PCR, leading to the misidentification of heterozygotes as homozygotes due to reduced peak/band intensity of the poorly amplified allele (Gagneux et al. 1997a), or it may also be caused by variation in the flanking region used by a PCR primer so that the primer does not bind properly as in the case of null alleles. ‘False alleles’ (extra peaks arising due to non-specific binding or contamination) and electrophoresis artefacts can also confuse microsatellite scoring (Fernando et al. 2001). Genotyping errors can significantly affect the conclusions drawn from a particular study. The genetic inference of furtive mating by female chimpanzees outside their social groups is a much-cited example (conclusions later found to be false due to allelic dropout, Gagneux et al. 1997b, 2001). Over recent years, attention to genotyping error has gained more prominence in molecular ecology, especially in cases where template DNA may be low in quantity or quality, such as when non-invasive genotyping techniques or historical samples are used (e.g. museum specimens or fish scale archives [which can make a large source for genetic information (Nielsen et al. 1997; Knox et al. 2002; Finnegan and Stevens 2008)]). The importance and consequences of error, and how errors should be measured and reported, have been discussed, as have protocols for designing microsatellite studies to limit error (Taberlet et al. 1996; Bonin et al. 2004; Broquet and Petit 2004; Hoffman and Amos 2005; Pompanon et al. 2005; Johnson and Haydon 2007; Täubert and Bradley 2008; Morin et al. 2009).

In recent decades the Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) has suffered declines in abundance across its entire range due to a number of factors (see Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, supplement 1, 1998; WWF 2001). Increased marine mortality is considered an important aspect of the observed decline (Jonsson and Jonsson 2004; Potter et al. 2004; Friedland et al. 2009), yet the ecology of anadromous S. salar during marine migration is poorly understood and remains a major challenge in managing declines of this economically and culturally important species. This and similar issues have recently led to several projects using or aiming to use genetic stock identification to assign marine caught fish to their rivers/regions of origin (e.g. Gauthier-Ouellet et al. 2009; Griffiths et al. 2010; also the ‘SALSEA-Merge’ project, of which the present study is part (www.nasco.int/sas/salseamerge.htm)). Key goals of such studies are to elucidate stock composition of intermingled stocks on common migration routes or feeding grounds, and/or to reveal stock-specific patterns of migration. In light of the species’ ability to migrate over distances of up to several thousand kilometres, the need to generate genetic data for baseline populations across the entire range, or as much of it as possible, is crucial to ensure studies are as informative as possible. Necessarily, multiple laboratories must collaborate and calibrate genetic data so that a standardized microsatellite database can be created. Despite the commercial and cultural importance of Atlantic salmon, as well as the existence of numerous studies and research groups using microsatellite data, a large-scale multi-laboratory microsatellite validation exercise has not previously been undertaken for this species. Validation has also not been previously undertaken for earlier datasets such as those for allozymes, significantly limiting the synthesis value of allozyme data from across the species’ range (Verspoor et al. 2005).

Here we detail microsatellite standardization across 12 laboratories. This included a detailed analysis of the degree of genotyping error, the partitioning of the causes of this error and the distribution of this error across laboratories using differing genotyping platforms and methods, and across loci of different size ranges and repeat motifs. We provide a retrospective discussion of the challenges faced while integrating databases in this context, and provide advice and recommendations for future collaborative research projects.

Materials and methods

Standardization and validation of microsatellite data

Consortium members and selection of loci

Twelve institutions comprise the genetic consortium of the SALSEA-Merge project. The consortium agreed the use of a microsatellite panel of fifteen loci (Verspoor and Hutchinson 2008; Olafsson et al. 2010) consisting of: SsaF43 (Sánchez et al. 1996), Ssa14, Ssa289 (McConnell et al. 1995), Ssa171, Ssa197, Ssa202 (O’Reilly et al. 1996) SSsp1605, SSsp2201, SSsp2210, SSsp2216, SsspG7 (Paterson et al. 2004), SsaD144, SsaD486, SsaD157 (King et al. 2005) and SSsp3016 (unpublished, GenBank number AY37820). Additionally, a number of laboratories also routinely genotype Ss osl 85 (Slettan et al. 1995) and this has also been included in the present study. Five of the chosen loci possess dinucleotide repeat motifs, and 11 tetranucleotide repeats.

Genotyping of standard sample set

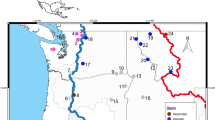

In order to standardize microsatellite scores between laboratories, two 96-well plates were prepared containing template DNA from samples representing the widest coverage of the range of S. salar as was practicable (Matis-Prokaria, Iceland, hereafter referred to as the ‘control plates’; Table 1). PCR cycle conditions, thermocyclers used and multiplexes varied across laboratories, as did genotyping platform, size standard, etc., for capillary or slab-gel electrophoresis. Similarly, different fragment analysis software packages were used for sizing microsatellite alleles, each associated with the particular genetic analyzer used for electrophoresis (Table 2). One laboratory (Laboratory D) used different PCR primers to the other laboratories for loci SSsp1605 and SSsp2216 (primers were redesigned to prevent allele overlap in multiplex reactions).

Some institutions did not genotype all 16 loci, notably Laboratories E and F had collaborated on a previous project in which they utilised 11 of the 16 loci. Other laboratories genotyped only those loci that they routinely worked with (Table 3), with eight genotyping 15 of the 16 loci, one 12 loci and one all 16 loci; a number of laboratories did not genotype SsaD486 due to the marked lack of genetic variation at this locus in Europe.

Generation of standard allele sizes

After genotyping control plate samples, genotypes were submitted to Exeter University for generation of standardization rules. Standardization involved several steps. First, spreadsheets for each locus were created containing the control plate sample genotypes for all laboratories. A list of all the alleles scored by each laboratory at each locus was then generated using the allele count function in Microsatellite Analyzer (MSA, Dieringer and Schlötterer 2002). For each locus, lists of allele counts for each laboratory were aligned by cross-referencing with the sample genotypes in the control plate genotype spreadsheets. Once allele lists were aligned, standard allele scores were designated for each locus: if two or more labs scored the data identically at a particular locus their alleles were designated as the ‘baseline alleles’ for standardization; if no two laboratories scored the data in the same way, one laboratory was nominated as the baseline; if there were multiple groups of laboratories that shared allelic scoring patterns the one with the most members was designated as the baseline. The size difference between the allele lists from each laboratory and the baseline allele list were then calculated. It was then possible to generate a database of standard allele scores by adding to or subtracting from the observed data the size difference between a laboratory’s allele sizes and the nominated baseline size, as appropriate for each locus in question (hereafter referred to as ‘standardization rules’).

Dealing with scoring inconsistencies

In some laboratories various scoring inconsistencies were observed (alleles of unusual size or incorrect repeat type, detailed in the “Results” section). Where these were particularly problematic, further correspondence, analyses of microsatellite data and/or re-genotyping were necessary to generate a consistent allele list. Standardization processes were then repeated to generate new factors for standardization to the baseline allele sizes as necessary.

Some inconsistencies (unusual alleles appearing in the data from some laboratories, but not others) were associated with particular individual samples in the control plates. These were investigated as potential Atlantic salmon/brown trout (Salmo trutta L.) hybrids (S. salar × S. trutta) by amplification of 5S rDNA and subsequent agarose gel electrophoresis (Pendas et al. 1995).

Re-screening of samples

After the standardization rules had been generated (as described above), the results were checked by re-screening a selection of samples (120–216 samples, depending on the locus) at a single laboratory. Each laboratory donated samples that had been genotyped at all relevant loci (i.e. loci they routinely genotype) and for which their genotypes had already been converted to the standard allele sizes. Genotypes for these samples were then generated in the re-screening laboratory and scored double-blind. The standardization rules pertaining to the re-screening laboratory were then used to generate standard allele sizes. The two sets of data (standardized allele sizes from the donating laboratory and the re-screening laboratory) were examined for any inconsistencies with the original standardization rules generated above.

Error estimation

Identifying consensus genotypes

After standardization rules had been established, all sample genotypes for each laboratory were converted to the standard allele sizes. By examining the standardized genotypes for each individual at a given locus across laboratories, consensus genotypes were identified for each individual in the control plates. Comparison of laboratory genotypes with the consensus genotype allowed the identification of genotyping errors. Errors were identified in the original datasets that were submitted, and in datasets after the standardization process was complete and correspondence regarding sizing inconsistencies had taken place (Fig. 1). Post-standardization datasets included corrected data from laboratories that had re-genotyped and re-analyzed data to eliminate scoring inconsistencies, as well as corrected data from the automatic removal of size-shift errors by the standardization process (see below).

Estimation of error rates

Allelic error rates were calculated for each laboratory at each locus following Pompanon et al. (2005). Using this approach allelic error (e a) is defined as:

where ma is the number of allelic mismatches, and 2nt is the number of replicated alleles. Here, as an individual laboratory’s genotypes can be determined as correct or incorrect by reference to the consensus genotype, for each locus it is also possible to determine individual laboratory error rates using the same formula, with 2nt as the total number of alleles genotyped at a particular locus for that laboratory.

Sources of error

Size shifts. In addition to calculating total errors, errors were apportioned into particular categories. ‘Size shift errors’ occur due to the fact that the electrophoretic size difference observed between two adjacent alleles does not necessarily correspond to the exact repeat unit difference between them. For example, the observed difference in size between two adjacent alleles at a tetranucleotide locus can be greater than or less than exactly 4 base-pairs. When this occurs, alleles towards the extremities of a locus’ size-range can appear to be out of alignment with the repeat pattern (explained further in Fig. 2). It can be difficult to assign these alleles to the correct allele size and a ‘size-shift’ may then occur where an allele is incorrectly scored by a factor of one complete repeat unit. This size-shift error can be considered to be consistent if all the alleles below (or above) a certain size are treated in the same way by a particular laboratory, in which case an apparent ‘jump’ in the data can be seen (and accounted for) when comparing data from the laboratory that has made the error with data from one that has not. Similar issues can also lead to alleles of unusual size being observed within the region where the size-shift jump has been observed (i.e. a dinucleotide repeat in a tetranucleotide repeat locus, e.g. if the 108 bp in Fig. 2 was scored as such and not fitted into the tetranucleotide bin set). Here these kinds of error are described as ‘size-shift mis-scores’.

Example of how size-shift errors arise. Observed alleles towards the ends of the observed range of a locus may not always fit neatly into the nominal allele bins. In this example alleles observed at 130.4 and 126.2 bp can easily be assigned to the correct allele bin (130 and 126 bp, respectively). However, an observed 108.4 bp allele may be more difficult to assign, and, for example, may be incorrectly scored as 106 bp allele bin instead of being placed in the 110 bp bin

Other errors. ‘Mistaken alleles’ were defined when alleles of the correct repeat-length were observed (i.e. alleles that matched the locus’ repeat pattern, but were incorrectly scored; e.g. correct genotype 120/124 scored as 120/128) occurring randomly throughout a locus (i.e. they could not be explained by a size-shift pattern at the extremities of a locus’ range). Similarly, ‘incorrect repeat lengths’ occurred where an allele at a tetranucleotide locus had been scored with a dinucleotide repeat length, but haphazardly throughout the allele range for a particular locus and not associated with a size-shift region. Some genuine dinucleotide alleles exist in some of the tetranucleotide loci (based on inter-laboratory consensuses and/or direct sequencing (e.g. see results for SSsp1605) presumably due to a 2 bp insertion/deletion) and these were not counted as errors.

Typographical errors were also denoted (e.g. if an allele of size 212 bp was scored as 122 bp, where 122 bp was well out of range for the locus). ‘Sample swap’ errors were recorded where it was obvious that a spreadsheet handling error or a possible methodical error in the laboratory had led to incorrect scores, e.g. three identical genotypes in a row where this should not be the case on the basis of the consensus genotypes.

Apparent allelic dropouts were counted in the data where a genotype lacked an allele relative to the consensus genotype. This form of error could have arisen in the data presented here either due to genuine allelic dropout or due to errors in genotype scoring during analysis (a genuine allele not called during allele-scoring), hence these errors were classified as ‘assumed dropout’.

Finally, all errors were broadly grouped into ‘analytical error’ (size shifts, mistaken alleles, mis-scores), ‘clerical error’ (typographical and sample swap errors) and ‘dropout error’ (large and small allele assumed dropouts combined) categories.

Statistical analysis of error. After calibration, a frequency histogram of all errors (for all loci across all laboratories) was made and the distribution of error examined. Outlying errors were examined to inform choice of potential explanatory factors of error for statistical examination. A Chi-square test was then carried out to assess a possible association of error with repeat type. The proportion of errors above and below a 2% threshold for di- versus tetranucleotide loci was examined in a two-by-two contingency table. The 2% threshold was chosen as the cut-off for an acceptable level of genotyping error after investigation of the frequency histogram of error rate.

Results from one locus (SSsp1605, see below) suggested that errors may be more likely to occur when a laboratory is genotyping samples from outside their usual geographic range. This possibility was examined further by calculation of allelic error rates for each locus (across laboratories and prior to calibration) for North American samples and European samples separately (all laboratories in the standardization project are European). The hypothesis that North American samples might be more prone to error than European samples was statistically examined using Wilcoxon’s signed rank test. The sum of signed ranks (W±) was used as the critical value as recommended for small sample sizes (Zar 1999). Tests were made twice, once for all loci (minus SSsp1605, which was not calibrated for North American samples, thus error rates could not be estimated) and, secondly, with loci that were subject to size-shift errors removed from the analysis. This was done in order to assess potential bias due to some loci with size shifts being subject to very large outlying error rates when a large number of individuals were present with alleles in the affected size-range. If the range of a locus subject to a size-shift occurred within a particular region (North America or Europe) then a significant result may or may not be obtained simply due to a single major cause of error affecting a large number of individuals.

Another consideration was whether the effort that different laboratories made in genotyping had any outcome on the amount of allelic error rate observed. That is, some laboratories may have been more cautious than others in assigning genotypes and thus may have withheld more questionable genotypes. In this case a positive linear relationship may be expected between the proportion of samples genotyped and the degree of allelic error rate, since more cautious laboratories which genotyped fewer samples may have made fewer genotyping errors. Conversely, more errors might be expected to occur when fewer samples were genotyped if a relatively small proportion of samples genotyped indicated a poor PCR amplification and an associated ‘bad’ genotyping run. In this case a negative linear relationship might be expected between proportion of samples genotyped and error rate. To examine this, plots were made of allelic error rate against proportion of samples genotyped for each locus in each laboratory (after calibration).

Anonymity of laboratories is maintained throughout the paper. For clarity, a summary of the work-flow is provided (Fig. 1).

Results

Scoring inconsistencies and standardization

In general, scoring patterns between laboratories were consistent at most loci (i.e. allele size differences between laboratories followed a systematic pattern and loci were thus easy to calibrate), although some loci proved particularly problematic for a number of research groups (inconsistent scoring included the occurrence of alleles of unusual size or incorrect repeat type and are detailed below).

SSsp1605 showed a distinct geographic split in the allele patterns and sizes between North American and European populations. North American populations showed a 2 bp size-shift relative to European populations (SSsp1605 is tetranucleotide, this indel having been confirmed by direct sequencing [D. Knox and E. Verspoor, Marine Scotland, Freshwater Laboratory, unpublished data]). Additionally, dinucleotide repeat alleles were numerous in the North American samples genotyped in the control plates, but were not scored consistently between laboratories (i.e. laboratories differed in the number of dinucleotide repeat alleles they scored, or they scored the locus to a tetranucleotide repeat system only). These observations suggest a dinucleotide-tetranucleotide compound repeat may actually be more realistic at this locus. Conversely, only a single dinucleotide allele was observed in the European samples and was scored consistently by seven of the 11 labs genotyping this locus. Due to the inconsistencies between North American and European source populations at this locus, calibration was carried out only for the European populations. Interestingly, one laboratory (H) also reported single base-pair alleles at this locus in some populations (particularly prevalent in Russian samples, but otherwise no clear geographic pattern in frequency). Genotyping of another standard set of individuals including more North American alleles and individuals containing single base-pair alleles would be useful for the future, but was not possible with available resources during the course of this study.

Some inconsistencies (alleles of unusual size or incorrect repeat type) that initially confused the generation of standardization rules were found to be consistent with two individuals in the control plate. These individuals were discovered to be salmon × trout (S. salar and S. trutta) hybrids (one individual originating from the River Neva, Russia, the other from the River Figgjo, Norway).

Where laboratories had large numbers of genotyping errors at a particular locus relative to the consensus or allelic patterns, these were resolved through correspondence and/or additional genotyping and analysis (4 of 12 laboratories were affected).

Size shifts

Six loci were affected by ‘size-shift’ problems in at least one laboratory due to the allelic drift described above (Table 3; Fig. 2). For a single locus the greatest number of laboratories showing a size-shift was four (SSspG7 prior to calibration). SsaD144 also showed a characteristic double peak on some genotyping platforms compounding the problem of a drifting size pattern. Alternatively, where size-shift patterns occurred consistently at a particular locus for a particular laboratory (i.e. all alleles above or below a certain allele length fell out of pattern by a factor of a single repeat length) two standardization rules were applied to the locus in question, thus automatically correcting this error. Standardization rules were successfully generated for all laboratories.

Re-screening

Re-screening revealed that at one laboratory the original +4 standardization rule for one locus (Ssa197) determined from the calibration plate was no longer necessary. Upon investigation, this proved to be because that laboratory had changed their PCR protocol (a change in Taq polymerase used) after the calibration plate had been scored and that this resulted in a 4 bp shift in their Ssa197 allele scores. It was also seen that at a single laboratory there was a non-standard calibration needed at SsaF43 with the smallest alleles. This was noticed in the original calibration exercise, but after discussion with the laboratory was not included, with hindsight a wrong decision (at the time it was assumed to be an inconsistent error that would not be repeated, but in fact re-screening highlighted a consistent size-shift for the laboratory in question at this locus).

Of all re-screened samples further inconsistencies (differences between the original genotyping and rescreening) occurred where two samples had been mixed up. For other loci apart from Ssa197 and SsaF43, the proportion of genotypes with an inconsistency between the re-screen and original data varied from 0 (SSsp3016, SsaD486, Ssosl85) to 0.058 (SSsp2201); mean 0.020 ± 0.005. SSspG7 had the second highest inconsistency rate of 0.042.

Error estimation

Mean errors for each locus across laboratories ranged from 0.003 ± 0.001 (SsaD486) to 0.286 ± 0.112 (SSspG7) prior to standardization and from 0.002 ± 0.001 (SsaD486) to 0.039 ± 0.018 (Ss osl 85) after standardization (Table 4; for all errors by locus and laboratory before and after calibration, see Supplementary Data). Mean errors for each laboratory across loci varied from 0.002 ± 0.001 (Lab A) to 0.175 ± 0.060 (Lab K) prior to standardization and from 0.002 ± 0.001 (Lab A) to 0.027 ± 0.009 (Lab K) after calibration (Table 5; Supplementary Data). Global allelic error rates (allelic error rates across all laboratories) were reduced from 0.05 ± 0.01 initially to 0.01 ± 0.002 after calibration. It should be noted that calibration only improved error rates where laboratories previously had a size-shift error that could automatically be corrected during generation of standard allele sizes (as described) or where a laboratory revised their allelic scoring for a particular locus after correspondence and exchange of data during calibration to correct some of the inconsistencies described in the methods. Elsewhere, allelic error rates remained the same before and after calibration.

Sources of error

Most errors prior to standardization were analytical, i.e. errors that occurred during the scoring of allele sizes either by eye (alone) or in genotyping software (note that all software genotypes were also confirmed by eye). After standardization, which automatically removes all size-shift errors, most errors remained analytical or clerical, with the exception of SsaF43 where allelic dropout caused most errors (Table 6).

Statistical analysis of error

Frequency distributions of all error rates after calibration are shown in Fig. 3. Examination of large, outlying error rates in the dataset after calibration showed no apparent trends with respect to size range or polymorphism. Several dinucleotide loci appeared to be implicated in outlying large error rates, however, no statistical association between repeat type and proportion of error above and below the 2% threshold was evident (χ 2 = 0.93, 1 df, P > 0.05).

No statistically significant pattern of allelic error rate with geographic region (North America and Europe, Table 5) was observed, either including all loci (sum of signed ranks W-, 48, n = 15, P > 0.05) or including only loci not subject to size shifts (sum of signed ranks W-, 6, n = 8, P > 0.05).

There was much variation and no obvious trend with regard to genotyping effort (proportion of loci genotyped) and allelic error rate (data not shown).

Discussion

Calibration and standardization

In this study we illustrate the relative ease with which microsatellite data can be calibrated and standardized across multiple laboratories for use in conservation and management, providing an important and valuable resource for population genetic research through the generation of a standardized database for Atlantic salmon across its entire range.

Calibration was possible across 12 laboratories genotyping up to 16 loci using seven different genotyping platforms, multiple models of thermocycler, different fragment labelling systems, size-standards, Taq polymerase, multiplexes, labelling different primers (forward or reverse), using different fluorophores and in two cases (in one laboratory) even different primers. Although the use of different primers could present problems in later analysis, through the potential for differing rates of null alleles, their use did not present a problem during the current calibration process. Although similar exercises have been previously undertaken in a range of species on varying scales (This et al. 2004; Pasqualotto et al. 2007; Seeb et al. 2007; Doveri et al. 2008; Baric et al. 2008; Stephenson et al. 2009), calibration is often considered or found to be problematic (Weeks et al. 2002; Moran et al. 2006) and in some cases has not been possible (Hoffman et al. 2006).

Previous studies have recommended the use of allele ladders for calibration (LaHood et al. 2002; Moran et al. 2006): single tubes are made containing a range (ideally all) of the alleles present for a particular locus for the study species in question and genotyped as a control by multiple laboratories. Comparison of observed allele ladder genotypes and the nominated sizes for those alleles allows correction of population genotypes to the standard sizes and, if the ladder is run as a control during screening, future consistency is maintained. In this study although a specific allele ladder was not used, samples within the two control plates had been selected to include fish from across the full range of the species (Table 1). Subsequently, calibration was achieved through comparison of allele sizes at each locus across laboratories based on the control plates containing this standard set of samples from across the species’ range, thus presumably reflecting a wide representation of existing genetic variation. In the future, as the geographic sample baseline is made more comprehensive and additional populations are characterised, we anticipate that some new alleles outside the current range may be encountered. Thus, it is intended that aliquots of samples with new alleles will be made available to consortium members and other interested parties for additional calibration as required.

Nonetheless, some anomalies remained. For example, one laboratory reported unusual 1 bp alleles at one locus for several populations from Norway and Russia, which were not detected in other baseline populations. It is not easy to include such data in the standardized database and the alleles, although real (as confirmed by direct sequencing), were reported by only a single laboratory. Consequently, to maintain consistency across laboratories, these alleles were binned with the adjacent tetranucleotide alleles, although this obviously creates a loss of resolution at a single locus for some populations.

The presence of two hybrids between S. salar and S. trutta in the control plate caused some initial confusion in the process of standardization, as different laboratories treated the presence of anomalous allele sizes differently in their data. Hybridization has similarly caused difficulties in microsatellite standardization in the past (e.g. between O. mykiss and O. clarki, Stephenson et al. 2009). For future standardization efforts, it is sensible to recommend screening of samples to be used for data exchange between laboratories to identify hybrids, especially when hybridization between the study organism and related species is known to occur, as is the case in salmonids.

The identification of the Ssa197-shift during the final re-screening illustrates the need for this stage. It also illustrates the need for controls to be run when changing any of the protocols within a laboratory and further highlights an advantage of using an allele ladder method. The identification of the non-standard conversion factor at SsaF43 illustrates the need to have the full range of alleles included on a calibration plate.

Of necessity, projects must to some extent balance their choice of approach against available finances, current resources and existing data. In the future, the construction of allele ladders containing the full range of alleles observed thus far for each locus used would be advantageous (and experience in Pacific salmonids shows that the use of allele ladders allows new laboratories to become instantly standardized and to produce high quality data [P. Moran, pers. comm.]). Although there is no guarantee that allele ladders will include all alleles that will ultimately be encountered (as is also true of the control-plate approach used here), in practice missing alleles in the ladder do not necessarily compromise utility (Lahood et al. 2002) and new alleles can easily be added to the pool used to construct the ladder, prior to redistribution. Sustained funding is valuable for the continuing success of exchange, compilation and distribution of data, and an important point is that researchers should at least plan/budget for some on-going/additional calibration.

Estimation of genotyping error

Calibration and standardization enabled an assessment of genotyping error. Similarly to other studies (e.g. with slab-gel sequencers, Ewen et al. 2000), most errors observed occurred at the analytical stages, i.e. errors associated with the binning of alleles or data-handling. Allelic dropout was the major cause of error at only one of the 16 loci (SsaF43, after calibration). A large number of errors occurred due to size shifts, this cause of error giving rise to very large outlying error rates at some loci (prior to calibration). Interest in standardization is evident in the literature and programmes have been developed to allow the combination of data (Täubert and Bradley 2008), to examine issues of inconsistency such as size shifts (Morin et al. 2009 [these programmes did not exist when this project began]), as well as to examine the extent of ‘false alleles’ and allelic dropout even where reference data are not available (Johnson and Haydon 2007).

Previous studies have suggested that errors may be associated with modal allele size at a locus and locus polymorphism (Hoffman and Amos 2005). There is also a perceived wisdom that dinucleotides can be particularly problematic to score: often dinucleotides possess peaks with a so-called ‘hedgehog’ topography (i.e. lots of stutter) and it can be difficult to determine whether a peak is homo- or heterozygous and which peaks represent the actual allele(s). Conversely, Moran et al. (2006) have recommended the use of polymorphic dinucleotide loci with an intermediate degree of polymorphism since they occupy little of the available size range on an electrophoretic instrument, thus allowing more opportunity for ‘size-plexing’ microsatellites with the same fluorophore in a single PCR reaction; additionally, many dinucleotides may be available that do not show stutter (true in many salmonids), and tetranucleotides may be more prone to inconsistencies in mobility, thus making standardization between labs more difficult (Moran et al. 2006). Here, no clear associations were found between degree of error and locus size range, number of alleles or repeat type. However, the early agreement by many laboratories to a standard panel of loci, known to be generally free of scoring errors, may explain why no clear associations were observed. The chosen panel of loci resulted from an informal meeting held in West Virginia in 2004 in which the choices were made by a number of laboratories interested in studying the genetics of Atlantic salmon (see Verspoor and Hutchinson 2008). Although not in use by all laboratories, the fact that many had been using the panel, or a sub-set of loci from the panel, greatly aided the integration of historical data. Without such an agreement it would not have been possible to combine genetic data, as the potential for each laboratory to choose different loci would have been high considering there were many hundreds of microsatellites to choose from. Such a consideration is perhaps even more important for the future with the development of SNP technologies, for which there are potentially many hundreds of thousands of polymorphisms.

Allelic error rates showed no clear pattern associated with geographic region (North America vs. Europe), nor was a consistent relation between percentage of the control plates genotyped and allelic error rate found (data not shown). An additional aspect that would also be interesting to examine is how genotyping error affects the estimation of common population genetic statistics. With a number of laboratories showing differing degrees of genotyping error and genotyping the same set of samples, this would have been interesting to examine here. However, the set-up of the control plates was not undertaken with such a goal in mind and the small number of individuals per river (as few as two individuals in some cases) precluded a useful analysis.

Overall, it was found that some laboratories were less prone to making genotyping errors than others and some loci were less prone to errors than others, although as described this is not necessarily predictable on the basis of repeat type, size range or allele number. One important recommendation is to make locus choices on the basis of prior genotyping experience and, with regard to collaboration and interchange of data, perform an initial small-scale calibration using a wider range of loci than intended for final use. In this way any locus that was considered to be reliable by a single laboratory, but for which inter-laboratory calibration reveals errors or difficulties, can be eliminated from the study and the most reliable set can be calibrated at a larger scale and used for the future (similar parallels regarding this point have been observed in the calibration of genetic data for Pacific salmonids [P. Moran, pers. comm.]).

In this study, calibration reduced errors significantly. Pompanon et al. (2005) address solutions to genotyping error and provide a work-flow to minimize error. Assessing consistency of microsatellite genotypes with independent data is recommended as a final step, prior to the determination of the reliability of the data. Some of these errors, such as size shifts, or consistently mis-calling a particular allele, would not be readily rectified through ‘standard’ intra-laboratory replicate genotyping as is routine and recommended (Bonin et al. 2004; Hoffman and Amos 2005). Thus, calibration is to be advised even where future collaboration is not the final goal as a means to improve the quality of microsatellite datasets. In the past, other authors have called for the presentation of an estimate of error alongside genetic studies as the equivalent of presenting P-values in traditional statistics (Bonin et al. 2004; Broquet and Petit 2004) and this is a call that can be reiterated here.

Concluding remarks

The standardization described here will allow the generation of a pan-European microsatellite genetic database for Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar. Thus, genetic assignment of marine caught fish to rivers or regions of origin across most of the European range of Atlantic salmon will be possible and the freshwater origins of migrating and/or feeding Atlantic salmon caught in intermixed stocks may be elucidated. As the marine survival of Atlantic salmon has declined dramatically over recent decades (Jonsson and Jonsson 2004; Potter et al. 2004; Friedland et al. 2009), this will represent a much-needed and significant contribution to the underlying knowledge necessary to mitigate declines of this culturally and economically important fish.

Although single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) overcome some of the problems associated with microsatellites (homoplasy, null alleles, variable mutation models and sparsely distributed loci, Morin et al. 2004; Seddon et al. 2005; Kohn et al. 2006), and are likely to find rapidly increasing use in the future, recent studies suggest that, for the time being, a combination of microsatellites and SNPs can provide more robust information for population genetic analyses (Narum et al. 2008).

References

Baric S, Monschein S, Hofer M, Grill D, Via Dalla J (2008) Comparability of genotyping data obtained by different procedures an inter-laboratory survey. J Hortic Sci Biotechnol 83:183–190

Bonin A, Bellemain E, Eidesen Bronken P, Pompanon F, Brochmann C, Taberlet P (2004) How to track and assess genotyping errors in population genetic studies. Mol Ecol 13:3261–3273

Broquet T, Petit E (2004) Quantifying genotyping errors in noninvasive population genetics. Mol Ecol 13:3601–3608

Callen DF, Thompson AD, Shen Y, Phillips HA, Richards RI, Mulley JC, Sutherland GR (1993) Incidence and origin of null alleles in the (AC)n microsatellite markers. Am J Hum Genet 52:922–927

Delmotte F, Leterme N, Simon C-J (2001) Microsatellite allele sizing: difference between automated capillary electrophoresis and manual technique. BioTechniques 31:810–818

Dieringer D, Schlötterer C (2002) Microsatellite analyser (MSA): a platform independent analysis tool for large microsatellite data sets. Mol Ecol Notes 3:167–169

Doveri S, Gil FS, Díaz A, Reale S, Busconi M, Câmara Machado DA, Martín A, Fogher C, Donini P, Lee D (2008) Standardization of a set of microsatellite markers for use in cultivar identification studies in olive (Olea europaea L.). Sci Hortic 116:367–373

Ewen KR, Bahlo M, Treloar SA, Levinson DF, Mowry B, Barlow JW, Foote SJ (2000) Identification and analysis of error types in high-throughput genotyping. Am J Hum Genet 67:727–736

Excoffier L, Heckel G (2006) Computer programs for population genetics analysis: a survival guide. Nat Rev Genet 7:745–758

Fernando P, Evans BJ, Morales JC, Melnick DJ (2001) Electrophoresis artefacts – a previously unrecognized cause of error in microsatellite analysis. Mol Ecol Notes 1:325–328

Finnegan AK, Stevens JR (2008) Assessing the long-term genetic impact of historical stocking events on contemporary populations of Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar. Fish Manage Ecol 15:315–326

Friedland KD, Maclean JC, Hansen LP, Peyronnet AJ, Karlsson L, Reddin DG, Maoileidigh NO, McCarthy JL (2009) The recruitment of Atlantic salmon in Europe. ICES J Mar Sci 66:289–304

Gagneux P, Boesch C, Woodruff DS (1997a) Microsatellite scoring errors associated with non-invasive genotyping based on nuclear DNA amplified from shed hair. Mol Ecol 6:861–868

Gagneux P, Woodruff DS, Boesch C (1997b) Furtive mating in female chimpanzees. Nature 387:358–359

Gagneux P, Woodruff DS, Boesch C (2001) Furtive mating in female chimpanzees (vol 387, pp 358, 1997) Nature 414:508

Gauthier-Ouellet M, Dionne M, Caron F, Kind TL, Bernatchez L (2009) Spatiotemporal dynamics of the Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) Greenland fishery inferred from mixed-stock analysis. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 66:2040–2051

Glaubitz JC, Rhodes OE, Dewoody JA (2003) Prospects for inferring pairwise relationships with single nucleotide polymorphisms. Mol Ecol 12:1039–1047

Griffiths AM, Machado-Schiaffino G, Dillane E, Coughlan J, Horreo JL, Bowkett AE, Minting P, Toms S, Roche W, Gargan P, McGinnity P, Cross T, Bright D, Garcia-Vázquez E, Stevens JR (2010) Genetic stock identification of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) populations in the southern part of the European range. BMC Genet 11:31

Haberl M, Tautz D (1999) Comparative allele sizing can produce inaccurate allele size differences for microsatellites. Mol Ecol 8:1347–1349

Hoffman JI, Amos W (2005) Microsatellite genotyping errors: detection approaches, common sources and consequences for paternal exclusion. Mol Ecol 14:599–612

Hoffman JI, Matson CW, Amos W, Loughlin TR, Bickham JW (2006) Deep genetic subdivision within a continuously distributed and highly vagile marine mammal, the Steller’s sea lion (Eumetopias jubatus). Mol Ecol 15:2821–2832

Hudson ME (2008) Sequencing breakthroughs for genomic ecology and evolutionary biology. Mol Ecol Resour 8:3–17

Johnson PCD, Haydon DT (2007) Maximum-likelihood estimation of allelic dropout and false allele error rates from microsatellite genotypes in the absence of reference data. Genetics 175:827–842

Jonsson B, Jonsson N (2004) Factors affecting the marine production of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Can J Fish Aquat Sci 61:2369–2383

King TL, Eackles MS, Letcher BH (2005) Microsatellite DNA markers for the study of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) kinship, population structure, and mixed-fishery analyses. Mol Ecol Notes 5:130–132

Knox D, Lehmann K, Reddin DG, Verspoor E (2002) Genotyping of archival Atlantic salmon scales from northern Quebec and West Greenland using novel PCR primers for degraded mtDNA. J Fish Biol 60:266–270

Kohn MH, Murphy WJ, Ostrander EA, Wayne RK (2006) Genomics and conservation genetics. Trends Ecol Evol 21:629–636

LaHood ES, Moran P, Olsen J, Stewart Grant W, Park LK (2002) Microsatellite allele ladders in two species of Pacific salmon: preparation and field-test results. Mol Ecol Notes 2:187–190

McConnell S, Hamilton L, Morris D, Cook D, Paquet D, Bentzen P, Wright J (1995) Isolation of salmonid microsatellite loci and their application to the population genetics of Canadian east coast stocks of Atlantic salmon. Aquaculture 137:19–30

Moran P, Teel DJ, LaHood ES, Drake J, Kalinowski S (2006) Standardising multi-laboratory microsatellite data in Pacific salmon: an historical view of the future. Ecol Freshw Fish 15:597–605

Morin PA, Luikart G, Wayne RK, The SNP Workshop Group (2004) SNPS in ecology, evolution and conservation. Trends Ecol Evol 19:208–216

Morin PA, Manaster C, Mesnick SL, Holland R (2009) Normalization and binning of historical and multi-source microsatellite data: overcoming the problems of allele size-shift with ALLELOGRAM. Mol Ecol Resour 9:1451–1455

Narum SR, Banks M, Beacham TD, Bellinger MR, Campbell MR, Dekoning J, Elz A, Guthrie CM III, Kozfkay C, Miller KM, Moran P, Phillips R (2008) Differentiating salmon populations at broad and fine geographical scales with microsatellites and single nucleotide polymorphisms. Mol Ecol 17:3464–3477

Nielsen EE, Hansen MM, Loeschcke V (1997) Analysis of microsatellite DNA from old scale samples of Atlantic salmon Salmo salar: a comparison of genetic composition over 60 years. Mol Ecol 6:487–492

O’Reilly PT, Hamilton LC, McConnell SK, Wright JM (1996) Rapid analysis of genetic variation in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) by PCR multiplexing of dinucleotide and tetranucleotide microsatellites. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 53:2292–2298

Olafsson K, Hjorleifsdottir S, Pampoulie C, Hreggvidsson GO, Gudjonsson S (2010) Novel set of multiplex assays (SalPrint15) for efficient analysis of 15 microsatellite loci of contemporary samples of the Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Mol Ecol Resour 10:533–537

Pasqualotto AC, Denning DW, Andersen MJ (2007) A cautionary tale: lack of consistency in allele sizes between two laboratories for a published multilocus microsatellite typing system. J Clin Microbiol 45:522–528

Paterson S, Piertney SB, Knox D, Gilbey J, Verspoor E (2004) Characterization and PCR multiplexing of novel highly variable tetranucleotide Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) microsatellites. Mol Ecol Notes 4:160–162

Pendas AM, Moran P, Martinez JL, Garcia-Vazquez E (1995) Applications of 5S rDNA in Atlantic salmon, brown trout, and in Atlantic salmon × brown trout hybrid identification. Mol Ecol 4:275–276

Pompanon F, Bonin A, Bellemain E, Taberlet P (2005) Genotyping errors: causes, consequences and solutions. Nat Rev Genet 6:847–859

Potter ECE, Crozier WW, Schön P-J, Nicholson MD, Maxwell DL, Prévost E, Erkinaro J, Gųdbergsson G, Karlsen L, Hansen LP, Maclean JC, Maoiléidigh NO, Prusov S (2004) Estimating and forecasting pre-fishery abundance of Atlantic salmons (Salmo salar L.) in the Northeast Atlantic for the management of mixed-stock fisheries. ICES J Mar Sci 61:1359–1369

Sánchez JA, Clabby C, Ramos G, Blanco D, Flavin F, Vázquez E, Powell R (1996) Protein and microsatellite single-locus variability in Salmo salar L. (Atlantic salmon). Heredity 77:423–432

Seddon JM, Parker HG, Ostrander EA, Ellegren H (2005) SNPs in ecological and conservation studies: a test in the Scandinavian wolf population. Mol Ecol 14:503–511

Seeb LW, Antonovich A, Banks MA, Beacham TD, Bellinger MR, Blankenship SM, Campbell MR, Decovich NA, Garza JC, Guthrie CM III, Lundrigan TA, Moran P, Narum SR, Stephenson JJ, Supernault KJ, Teel DJ, Templin WD, Wenburg JK, Young SF, Smith CT (2007) Development of a standardized DNA database for Chinook salmon. Fisheries 11:540–549

Slettan A, Olsaker I, Lie Ø (1995) Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar, microsatellites at the Ssosl25, Ssosl85, Ssosl311 and Ssosl417 loci. Anim Genet 26:281–282

Stephenson JJ, Campbell MR, Hess JE, Kozfkay C, Matala AP, McPhee MV, Moran P, Narum SR, Paquin MM, Maureen OS, Small P, Van Doornik DM, Wenburg JK (2009) A centralized model for creating shared, standardized, microsatellite data that simplifies inter-laboratory calibration. Conserv Genet 10:1145–1149

Taberlet P, Griffin S, Goosens B, Questiau S, Manceau V, Escaravage N, Waits LP, Bouvet J (1996) Reliable genotyping of samples with very low DNA quantities using PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 24:3189–3194

Täubert H, Bradley DG (2008) combi.pl: a computer program to combine data sets with inconsistent microsatellite marker size information. Mol Ecol Resour 8:572–574

This P, Jung A, Boccacci P, Borrego J, Botta R, Costantini L, Crespan M, Dangl GS, Eisenheld C, Ferreira-Monteiro F, Grando S, Ibáñez J, Lacombe T, Laucou V, Magalhães R, Meredith CP, Milani N, Peterlunger E, Regner F, Zulini L, Maul E (2004) Development of a standard set of microsatellite reference alleles for identification of grape cultivars. Theor Appl Genet 109:1448–1458

Verspoor E, Hutchinson P (2008) Report of the symposium on population structuring of Atlantic salmon: from within rivers to between continents. NASCO report ICR(08)8, 23 pp. http://www.nasco.int/sas/pdf/reports/misc/

Verspoor E, Beardmore JA, Consuegra S, Garcia de Leaniz C, Hindar K, Jordan WC, Koljonen M-L, Makhrov AA, Paaver T, Sánchez JA, Skaala Ø, Titov S, Cross TF (2005) Population structure in the Atlantic salmon: insights from 40 years of research into genetic protein variation. J Fish Biol 67(suppl A):3–54

Weeks DE, Conley YP, Ferrell RE, Mah TS, Gorin MB (2002) A tale of two genotypes: consistency between two high-throughput genotyping centres. Genome Res 12:430–435

WWF (2001) The status of wild atlantic salmon: a river by river assessment. WWF http://assets.panda.org/downloads/salmon2.pdf. Accessed March 2010

Zar JH (1999) Biostatistical analysis, 4th edn. Prentice-Hall, London

Acknowledgments

This work forms part of the SALSEA-Merge research project (Project No. 212529) and was funded by the European Union under theme six of the 7th Framework programme. In addition to samples contributed by the authors, thanks go to T. King, P. O’Reilly, L. Bernatchez, M.-L. Koljonen, A. Veselov, A. J. Jensen, J. Lumme and S. Kaliuzhin for additional samples used in the calibration exercise. PMcG, TC & JC were funded by the Beaufort Marine Research Award with the support of the Marine Institute under the Marine Research Sub-Programme of the National Development Plan (Ireland) 2007–2013. Thanks to James Cresswell (University of Exeter) for statistical advice and useful discussions. We would also like to thank Paul Moran (NW Fisheries Science Center, Seattle, USA) and one anonymous reviewer for their detailed and constructive comments on the original manuscript.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ellis, J.S., Gilbey, J., Armstrong, A. et al. Microsatellite standardization and evaluation of genotyping error in a large multi-partner research programme for conservation of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.). Genetica 139, 353–367 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10709-011-9554-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10709-011-9554-4